Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.41 n.2 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v41i2.2

ARTICLES

A critical evaluation of religious syncretism among the Igbo Christians of Nigeria1

E.C. AnizobaI; S.I. AandeII

IDepartment of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria. E-mail: emmanuel.anizoba@unn.edu.ng; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2399-6328

IIUniversity of Mkar, Mkar, Benue State. E-mail: aandesimeoniember@gmail.com; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6685-8937

ABSTRACT

Syncretism has remained a persistent issue among the Igbo-speaking Christians of Nigeria. This is observed in the double allegiance of faith among many of them who, interestingly, are devotees of both Christian and African traditional beliefs/systems. Besides the belief in ritualistic charms, many Igbo/Igbo-speaking Christians consult diviners for various reasons, including security and prosperity, causes of illness and death, ways of preserving life, as well as to discern the mind of God about one's future and destiny. Moreover, traditional oath-taking among other African traditional religious practices is common among many Igbo Christians. This article sets out to critically examine the factors that are responsible for the persistence of religious syncretism among the Igbo Christians. The study adopts a qualitative phenomenological research design and descriptive method for data analysis. Personal interviews and library resources constitute the primary and secondary sources of data, respectively. The findings reveal that life-threatening factors such as illness, disease, insecurity, and fear are some of the principal causes of religious syncretism among the Igbo Christians.

Keywords: Critical, Evaluation, Religious syncretism, Igbo Christians

Trefwoorde: Krities, Evaluasie, Godsdiens sinkretisme, Igbo Christene

1. INTRODUCTION

In present-day Nigeria, the Igbo and Igbo-speaking people are predominantly located in the south-eastern states of Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo. The Igbo people believe in a creator and god, whom they call ChukwuokikeAbiama (meaning"Almighty God"). According to Basden (1966), the Igbo have historically held ChukwuokikeAbiama as their spiritual guard and assistant, even before the advent of Christianity. Christianity was introduced to Igboland following the European colonisation in 1857 (Basden 1966). For Britain, however, Christianity quickly became a tool for exploiting the Igbo people both politically and economically. The Igbo's initial rejection of Christianity was not vehement. In other words, they neither readily converted nor were hostile to the new religion. By the 1900s, however, the Igbo began to associate Christianity with class, a higher social identity, and safety, which eventually lured many others to embrace the faith. At this point, missionaries were invited to set up churches and schools across Igboland. Such interventions, including the prohibition of the British Government's efforts to forcefully conscript some Igbo as laborers, were well received. On the other hand, the Igbo traditional belief system included (and still includes) other "lower deities" and providences, as well as the belief in spirits, magic, medicine, and ancestral curses. Within the context of Igbo cosmology, many Igbo believe that there are some mystic forces in the universe that can be accessed for either good or bad outcomes (Omoregbe 1999). According to Omoregbe, those with such access, including the priest-physicians, utilise it for good causes such as healing people and solving difficult problems. Others, however, employ their access for evil purposes such as impairment and disease. These statements attest to the presence of religious syncretism (a process of combining different religious practices) in Igboland. Stated broadly, the admixture of religious practices, especially by adherents of Christianity and African traditional religion is undeniable in modern Nigeria. Ejizu (1992) pointed out that, while Igbo Christians denounce the belief in and use of charms, and vigorously campaign against indigenous religious institutions and practices, many of them simultaneously strongly encourage certain basic attitudes and values that clearly derive from and affirm their faith in indigenous religion. Some scholars have done research on this dual practice. For example, Anene (1993) studied the popular Anioma Healing Ministry in Anambra state. This ministry is owned by the late prophet Eddy Okeke (alias Eddy Nawgu). According to Anene, the late prophet believed in God and angels, practised magic, revered the ancestors, and employed divination and sorcerers.

According to Informant 1 (2019, oral interview), religious syncretism often occurs when a foreign belief system and teachings are introduced and blended with an indigenous one. The new, hybrid religion then takes on a life of its own. This practice is most palpable in the Roman Catholic missionary accounts. For example, during the Roman Catholic Church's proselytising of animistic South America, tens of thousands of natives were baptised into the church without preaching the Gospel for fear of death; former temples were razed to make way for Catholic shrines and chapels. Native South Americans were allowed to substitute praying to their former idols (gods of water, earth, and air) with new images and saints of the Roman Catholic Church. That said, the natives' own traditional animistic religion was never fully replaced. Rather, it was adapted into the Catholic teachings for a new belief system to flourish.

To reiterate, the purpose of this research is to critically examine some of the syncretic practices among the Igbo, and why such practices have persisted after so many years of Christianity. With reference to disease causation, this study will be extremely important to the Igbo ethnic nation, Nigerians, and Africans at large. Some mystical agents in Igbo cosmology, including witches and sorcerers, Ogbanje, the breaking of taboos, and so on, are responsible for untimely deaths, infliction of diseases to mankind, and other related ailments.

2. METHODOLOGY

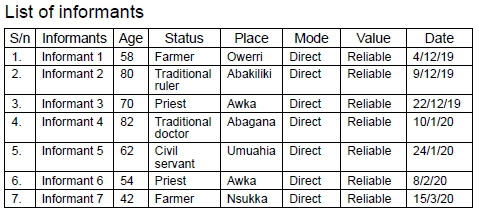

The study adopts a qualitative phenomenological research design and descriptive method of data analysis. Personal interviews form the primary sources of data collection, with seven informants chosen at random for the interview. They were given code names ranging from Informant 1 to Informant 7. These informants were diverse in terms of distribution of five states of Igboland, gender, occupation, and religious affiliation, with particular regard to Christianity and African traditional religion. Three of these informants are from the Nawgu community in Anambra State, home of the Anioma Healing Ministry, which forms a typical example for the research. The interview questions were semi-structured. This allowed the researcher to follow up on similar groups of interview questions based on the respondents' responses. All relevant issues guiding the conduct of the interview were followed. The informants were told that the information obtained from them will be used solely for this research. The period of the research was from 2017 to 2019, when fieldwork was conducted for the research.

3. OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS OF RELIGIOUS SYNCRETISM

According to Asogwa (2008), the term "syncretism" first appeared in the English lexicon in approximately 1681, and is derived from modern Latin syncretismus, meaning "a union of communities". Syncretism is traceable to Plutarch and thus references Cretans' readiness to syncretic differences in opposition to an enemy. In the 17th century, the term shifted its focus from "unification against a common enemy" to concerns about the "incompatibility of different forces", in an attempt to reconcile Aristotelian and Platonist philosophers, and care-formed theologians. In the 19th century, the term's meaning and usage shifted to the mixing of religious ideas and names of deities in the study of Greek and Roman religion. In religion studies, syncretism has received contested perspectives and interpretations (Droogers 1989). Asiegbu (2000), for example, describes syncretism as a process of combining different religious practices or beliefs, which may lead to a new synthesis or a strengthening, weakening or dissolution of old allegiances. It may indeed be viewed as an incorporation of incompatible beliefs or a reconciliation/fusion of different systems of belief. Therefore, religious syncretism implies the tolerance and acceptance of all religions and their world views. It is the belief that all religions lead to God and are capable of banqueting and salvaging the souls of their adherents.

4. PATTERNS OF SOME SYNCRETIC PRACTICES AMONG CHRISTIANS IN IGBOLAND

4.1 Practice of divination among some Christians

According to Informant 2 (2019, oral interview), some of the proceedings, where Igbo Christians mix aspects of Christianity with African traditional religious doctrines, nearly always happen during christening (naming) ceremonies. In this instance, some Christians go to the diviner to find out which particular soul reincarnated. Elsewhere, they first carry out African traditional religious naming rites, and later proceed to church for baptism and dedication. Okafor also suggests that, in most instances, diviners will be consulted before the selection of an Igbo traditional ruler who is a Christian. For this purpose, the candidate will be traditionally initiated into the Ozo title institution before being crowned king of a particular town. Often, this rite is performed in accordance with the "will of the gods of the land" to ascertain whether or not the candidate, initiated into this sacred institution, will make a good king.

According to Informant 1 (2019, oral interview), some of the reasons for the practice of divination among Christians include to find ways of consolidating personal security and wealth; to inquire into the nature and causes of illness/ death; to discover ways of preserving life and making progress; to discover the mind of God for the future and for one's destiny, and so on. Divination, therefore, illuminates suffering, alleviates doubts, and restores value and significance to the lives of such practitioners, especially in times of crises. The practice of divination is as old as our humanity. It exists in all the cultures of the world, in different ways, and in various forms. In the Old Testament, Moses warned the people of Israel against the practice of divination:

There must never be anyone among you who makes his son or daughter pass through fire, who practices divination, who is a soothsayer augur or sorcerer, who uses charms, consults ghosts or spirits, or calls up the dead. For the man who does these things is detestable to Yahweh your god (Deut. 18:9-14).

The catechism of the Roman Catholic Church also short-listed other forms of divination to be rejected:

Recourse to Satan or demons, conjuring up the dead or other practices falsely supposed to "unveil" the future. Consulting horoscopes, astrology, palm reading, interpretation of omens and lots, the phenomena of clairvoyance, and recourse to mediums all conceal a desire for power overtime, history and in the last analysis, other human beings, as well as a wish to conciliate hidden powers. They contradict the honour, respect, and loving fear that we owe to God alone (Maduka 1991:3).

The above-listed forms of divination derive from the desire to surpass human limitations and penetrate the future and the unknown. For Kasomo (2012), divination is an art or a practice of discovering the personal, human significance of future or, more commonly, present or past events. This suggests that divination is an inquiry into the existential meaning of human life, which can only be achieved through the manipulation and guidance of supernatural forces. Kasomo (2012) observed that diviners, witchdoctors, or sorcerers played (and continue to play) a key role in the protection of life from perceived enemies. Their knowledge and power enable them to proffer treatment for diseases, exorcism, and the incapacitation of an enemy. The practitioners also offer medicine for good fortune, love, success, security of person and property, and protection from sorcery and witchcraft (Peek 1991:103). This medicine could be in the form of herbs (and thus ingested), or as body parts from animals (and thus made into charms and amulets, which may be hung on certain parts of the body).

4.2 Reasons for divination

In Igboland, divination subsists in the failure of individuals to cope with crises as well as the fear of uncertainty. Diviners are widely regarded as gateways to the unveiling of the mysteries of human life. As such, some Christians approach diviners for answers to their circumstances as well as for information about future occurrences. According to Parrinder (1949:152),

the diviner seeks to interpret the mysteries of life, to convey the messages of the gods, give guidance in daily affairs, and settle dispute to uncover the past and look into the future.

For the Igbo, divination is called "igbaafa", and it represents a pivotal aspect of traditional religion. According to Metuh (1985), the role of the diviner is indispensable for the social, political, religious, and personal life of the Igbo. This explains why it is always difficult for some people to shrug off divination, even after conversion to Christianity. Hence, some Christians resort to divination not only to obtain knowledge about the future, but also and more so to discover ways of avoiding misfortunes such as sudden death and illness, as well as pacifying angry or revengeful ancestors. Often, some Christians approach diviners to know the "real" cause of their illness, and whether or not such causes are mystical and/or genetic. This behaviour underlines a crisis of faith as well as the difficulty of making the Christian faith an unadulterated part of their daily lives. For some people, this is a sign that Christian churches lack the power to address their material-spiritual problems and cannot, therefore, provide directives in times of crisis. The vast majority of Igbo writers blame this perception on the barrenness of Christian spirituality and contend that Christianity has failed to satisfy the spiritual desires of its members. Asiegbu (2000) suggests that the problem resides in the processes of keeping Igbo Christians true to their beliefs, and thus guaranteeing the relevance of Christianity to both their material and spiritual world view. Provided this gap exists between the two, the practice of divination will endure within what is a crisis of Christian faith.

4.3 Practice of charms alongside Christian faith and sacraments

According to Informant 3 (2020, oral interview), many alleged prophets of God in Igboland tenaciously believe in and practise the use of charms and amulets in their ministries. They do so fundamentally to perform miracles. Citing the late prophet Eddy Okeke (alias Eddy Nawgu of Anambra state) as an example, Okoye maintains that the late alleged prophet of God and founder of the popular Anioma Healing Ministry deeply believed in the use and efficacy of charms and amulets. Okeke (1989) mentions the names of some of the Hindu charms and talisman that Okeke himself used: the "Odo" talisman used for inducing signs and wonders; the "Odo" talisman used for destructive purposes, and the "Lindo" talisman used for multiple purposes and operations.

Not only did the prophet use charms and amulets; he also prepared them for his followers and clients. This is why Ukaegbu (2001) suggested that Eddy's death spelt doom for many business persons who received spiritual support from him in the form of "cultic staff" spiritual rings and other mystical objects used for multiple operations, including disappearance acts, and even charms for avoiding security operatives during illegal business trips and armed robbery operations. Informant 4 (2020, oral interview) stated that local drug cartels and peddlers use the charms collected from Eddy to evade law-enforcement officers, even in the most technologically advanced countries. He also suggested that the "staff of power", which Eddy gave to his clients, was a "one-touch" connection with the diabolical world. According to Okafor, the late prophet even gave his customers charms with which to trample upon and oppress their enemies. He also prepared charms that enabled them to intimidate people and snatch valuable belongings such as lands and spouses.

4.4 Reasons for charms

According to Informant 5 (2020, oral interview), there are reasons for the belief and practice of charms alongside the Christian faith among the Igbo people. These include a need for personal security, remedy against barrenness, protection against death, prevention of illness and misfortunes, enhancing one's business opportunities and progress, as well as attracting God's immediate intervention and other useful mystical powers of the universe. This shows a strong syncretistic practice in Igboland, where charms are used alongside Christian faith and sacraments. For such Christians, charms are unavoidable in an environment where life is not only insecure, but also and always under constant threat from unknown forces of evil. Njoku (2013) observed that, since institutionalised religion provides new values and satisfactory social groupings in an environment where the old African traditional religion had been demonised, individuals searching for affiliation with communities have found syncretistic practices more appealing and helpful for dealing with their uncertainties.

4.5 Practice of traditional oath-taking vs Christian oath-taking

According to Okeke et al. (2017), oath-taking strongly affirms the desire to do something, like making a promise that must be kept. People took oaths but carelessly defaulted in the specifications. It is the individual's responsibility to adhere strictly to the promise or prepare for what is usually a disastrous outcome. Oath-taking involves and demands a strong and all-embracing commitment because there is a tendency that one's whole life is implicated. Oath-taking solicits a measure of faithfulness and honesty, as the ties between the oath-taker and fulfiller assume the status of an unbroken chain. Symbolically, oath-taking demonstrates the degree of seriousness in a person's allegiance to processes and consequences. It is usually supported with a seal that remains a secret between the parties involved. This seal makes the enterprise definite so that it cannot be changed or argued about. This concept of a seal is akin to an oath that a man and woman take during marriage. It is usually sealed with blood as a mark of an indissoluble covenant, plan, and act. Consequently, the parties involved must do well not to contravene the oath, as the repercussions might be dire.

While explaining the nature and types of oath-taking, as well as the reasons for oath-taking, Okeke et al. (2017) noted that public oath-taking practices target individuals who aspire to or are in positions of authority within government. In this instance, a seal would normally represent the certificate of return. In a political context, defaulting leads to either indictment or prosecution according to the law of the country. Another type of oath-taking involves parties regarded as the "living dead" where the ancestors demand commitment, sincerity, fidelity, and uprightness from the individual. Those who know or have experienced the negative implications of this type of oath-taking never engage in it.

According to Informant 6 (2020, oral interview), the essential point about oath-taking is that it compels the parties concerned to avoid defaulting, especially for fear of misfortunes, punishment, or death. Some Christians prefer to swear by some divinity or African traditional religion sacred objects rather than by the Christian Bible. They contend that, unlike the Bible or Christian God, such divinities promptly and adequately mete out punishments for any breach of oath. Although this claim remains to be verified, according to Informant 7, it poses many problems for the Christian church and often leads to divisions between Christians and other members of the African traditional religion. As such, some Igbo devotees choose to swear by both the Christian and African traditional religion sacred artifacts, if only to justify the support of both sides. This, too, is syncretism in practice.

5. FINDINGS OF THE RESEARCH

This study revealed the following factors that may be responsible for the syncretist practices in Igboland:

1. The Igbo are traditionally spirit-conscious in nature: both human beings and spirits interact. Everything in the world has a spirit (spiritual dimension), which is always there to monitor people's daily activities. Therefore, when people with such spirit-conscious mentality are faced with certain problems and, particularly, feel that Christianity cannot help, they have recourse to fortune tellers, producers of charms, and diviners for solutions.

2. In Igbo cosmology, there is the belief in the existence of spirits, which drives the search for many things, including security of life. The people constantly fear uncertainties. The Igbo believe that there is an interaction between good human beings and spirits as well as between bad human beings and spirits. Bad spirits work with bad human beings to cause harm in much the same sense as good spirits do with good human beings. Hence, for some Christians, the best way to be safe is through the use of charms and amulets.

3. In Igbo cosmology, there are many consequences for the infringement of community laws and observances, including laws about burial, marriage, title, (new yam) festivals, priesthood pertaining to particular shrines and idols, installation of chiefs, and some local celebrations. Breaching these laws creates anxieties among many uninformed minds in a society where sin becomes automatic to the extent that one sins without knowing it. In other words, one becomes aware of one's transgressions either when the community imposes a penalty upon one or an inquiry is carried out into the cause of some mishap within one's family/life. At this juncture, one will be told by influential diviners that they have transgressed. The offenders are thus invited to appease the gods or pay some reparation to avert further repercussions. This appeasement is usually via some sacrifices and/or other specific rituals.

4. The Igbo believe strongly in the world and power of nature. For them, nature is deeper and more mysterious, and exercises much more impressionable influences than the technological world. This arguably is the reason why the Igbo associate freely with people who live around them. For instance, a Christian, who lives and mingles with ATR adherents, is often open to and can easily be influenced by the adherents' modes of thought and ways of life. In other words, some Christians have not fully absorbed Christianity; they leave some room for practising their traditions and traditional world views.

5. Lack of faith among the Igbo has been identified as one of the reasons for the belief and practice of religious syncretism. Although Onuzulike (2008) observed that African traditional religion is intertwined with African culture, some Christians find it difficult to practise both, because some African traditional religion cultures conflict with the Christian faith. This, in turn, has created confusion among many African Christians, especially among the Igbo who want to straddle both.

6. According to Maduka (1991:4),

leveling the nations of the world as one nation culturally is definitely not God's intention. The church is universal, not in cultural uniformity but in cultural diversity with unity of faith. Until this truth is well understood and put into practice, the unity which we ardently pray for will not be fulfilled.

A reflection on the above and other religious dialogues may be help resolve the indifference to the traditional world view. As the Christian church embraces dialogue with traditional religion and culture, previously held notions such as the need to save the sin-filled African traditional religion among Christians becomes untenable and paves the way for religious syncretism.

7. RECOMMENDATIONS

The solution to religious syncretism is to root Christianity in the cultural aspirations and religious responsiveness of the Igbo people. This would require an urgent intensification of theological education of Igbo Christians, if only to enhance a proper understanding of the nature of Christianity and its interactive modality with elements of culture and tradition. Such a theological enlightenment must begin with church leaders, religious educators and all other Christians in Igboland. The church in Igboland must teach members about a type of Christianity where God is known to them through Christ as their only saviour. In this instance, Christ is the centre of our lives.

As Christians, we live in a world of problems; yet we are not expected to be of the world. The Igbo are a people who theologically believe in the transformative and saving power of Jesus Christ. For them, this notion brings about eternal salvation and manifests itself in love, joy, peace, and gentleness. There is, therefore, no room for hate, war, and oppression. For this to happen, faith is necessary. It is also important that the church itself periodically undergoes revitalisation to check and renew its commitment to living according to the light and gospel of Jesus Christ as well as to avoid syncretism, irrespective of the belief in spirit and nature. Traditional institutions such as Ozo and its title-taking ceremonies should be explained to Igbo Christians, in order to clearly differentiate between acceptable methods of Christian initiation and to avoid the prevailing religious syncretism in Igboland. The Igbo people should also be consistent in naming their newborn babies, either through the circumstances of their birth or own names of choice rather than patronising the diviners.

8. CONTRIBUTION TO KNOWLEDGE

This study presents a compendium of knowledge on the subject matter. It specifically connects two diametrically opposed religious belief systems and practices as one complex whole through faith in God. This will help the Igbo people know about how some cultural practices, including the belief in charms, oath-taking, witchcraft, and so on, could affect their faith in Christ. If this study is applied or used in every nook and cranny of Igboland, Nigeria, it will help Africans and the entire world address those issues of religious syncretism that are prevalent in society.

9. CONCLUSION

A major concern of this research was to determine how authentic Igbo people are in practising Christianity in Igboland nowadays. The central question was: To what extent are Christians in Nigeria committed to the faith Igbo people received and profess, amidst continued influence of traditional values? According to this article, the Igbo are concerned with the Christian missionary method, which some people believe is inadequate; hence, the presence of religious syncretism. Other reasons for the practice of religious syncretism among the Igbo people include, but are not limited to, the fear of uncertainties. In Igbo cosmology, the basic and indispensable elements of the traditional religious belief system and practice were simply overtaken by and transposed and transformed into corresponding elements of the newfound religion (Christianity).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anene, O. 1993. Truth and the oral at Nawgu. Enugu: Hanoby. [ Links ]

Anizoba, E.C. 2020. Study of Igbo traditional beliefs in mystical causation of diseases and the Western germ theory. Unpublished PhD thesis, Nsukka: University of Nigeria. [ Links ]

Asiegbü, A.U. 2000. A crisis of faith and a quest for spirituality: An enquiry into some syncretistic practices among some Christians in Nigeria. Enugu: Pearl. [ Links ]

Asogwa, T.O. 2008. Half Christian half pagan: The dilemma of the Nigerian Christian. Enugu: Snaap. [ Links ]

Basden, G.T. 1966. Among the Nier Ibos. London: Frankcass and Co. Ltd. [ Links ]

Droogers, A. 1989. Syncretism: The problem of definition, the definition of the problem. In: J. Gort (ed.), Dialogue and syncretism: An interpretative approach (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans), pp. 10-20. [ Links ]

Ejizü, C.I. 1992. Cosmological perspective on exorcism and prayer-healing in contemporary Nigeria. In: C.U. Manus, L.N. Mbefor & E.E. Uzukwu (eds), Healing and exorcism: The Nigerian experience (Enugu: Snaap), pp. 11-23. [ Links ]

Kasomo, D. 2012. An assessment of religious syncretism. A case study in Africa. International Journal of Applied Sociology. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://article.sapub.org/10.5923.j.ijas.20120203.01.html [7 February 2019]. [ Links ]

Madüka, M. 1991. Need for sincere inculturation. Paper presented to the Catholic Priests of Awka Diocese, Anambra State. [ Links ]

Metüh, I.E. 1985. African religions in Western conceptual schemes. Ibadan: Pastoral Institute. [ Links ]

Njokü, M.G. 2013. Psychology of syncretistic practices within the church. Paper presented at the 3rd Synod of the Catholic Diocese of Enugu. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294727997_Psychology_of_Syncretistic_Practices_within_the_Church [7 February 2019]. [ Links ]

Okeke, C.O., Ibenwa, C.N. & Okeke, G.T. 2017. Conflicts between African traditional religion and Christianity in Eastern Nigeria: The Igbo example. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2158244017709322 [7 February 2019]. [ Links ]

Okeke, E. 1989. Professor Eddy mystic home of wonders. Current catalogue. 3rd edition. Nsukka: Afro Orbis Publishers. [ Links ]

Omoregbe, J.I. 1999. Comparative religion Christianity and other world religions in dialogue. Lagos: Joja Educational Research and Publishers Ltd. [ Links ]

Onüzülike, U. 2008. African crossroads: Conflicts between African traditional religion and Christianity. International Journal of the Humanities 6(2):163-170. DOI: 10.18848/1447-9508/CGP/v06i02/42362. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279533501_African_Crossroads_Conflicts_between_African_Traditional_Religion_and_Christianity [7 February 2019]. [ Links ]

Parrinder, G. 1949. West African religion. London: Epworth. The catechism of the Catholic Church (1995). Nairobi: Paulines. [ Links ]

Peek, P.M. (Ed.) 1991. African divination systems: Ways of knowing. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Ukaegbü, G. 2001. Cultism in the country. Daily Champion, 23 December. [ Links ]

Date received: 23 April 2021

Date accepted: 20 August 2021

Date published: 15 December 2021

1 This article is based on the doctoral thesis of the author (Anizoba 2020).