Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.41 suppl.31 Bloemfontein 2021

ARTICLES

Integrating spirituality in decision-making processes: the "Kairos experiences" in the "faith-based facilitation" process of the Salvation Army

S. Knecht

Mr. S. Knecht, Masters student at the University of South Africa, Salvation Army officer, St.-Georgen-Strasse 55, 8400 Winterthur, Switzerland. E-mail: stephan.knecht@heilsarmee.ch ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9049-8636

ABSTRACT

The resource of spirituality is often neglected in decisionmaking processes in Christian churches. This problem has also been recognised in the Salvation Army. In response, the so-called "Faith-Based Facilitation" (FBF) process was developed and introduced in 2010. A characteristic of the FBF process is the concept of the "Kairos experiences" as a key spiritual aspect. In the literature on the FBF process, there is a paucity of works on the nature of the "Kairos experiences", although a great emphasis is placed thereon. Thus, the problem arises as to how to deal with this phenomenon in practice. This article examines the concept "Kairos", by drawing on the philosophical and theological literature, with the aim of formulating a theological rationale for the FBF process and providing methodological aids in dealing with the "Kairos experiences". I argue that the disposition and spiritual competence of those involved are key to the integration of spirituality in decision-making processes.

Keywords: Christian spirituality, Decision-making, Faith-based facilitation, Kairos experiences

Trefwoorde: Christelike spiritualiteit, Besluitneming, Geloofgebaseerde fasilitering, Kairos ervarings

1. INTRODUCTION

I chair a meeting of the board of a Salvation Army2 congregation, of which I am the officer. The agenda includes the election of a new member of the board. The discussion begins after a short introduction with prayer and a biblical reflection. The names of possible candidates are mentioned, discussed, rejected again or noted down for further discussion. At the end of the session, I return home with an unpleasant gut feeling. I suddenly realise that the previous discussion was a mere exchange of opinions and not a real search for the will of God. The more I thought about our (unconsciously or thoughtlessly adopted) methodology of decision-making, the clearer it became to me that we were practising a so-called "book-cover spirituality": a prayer at the beginning, a prayer at the end, and in between a session similar to what could have taken place in secular organisations. All too often the business to be dealt with was merely framed by spiritual elements without being touched by them. I intuitively came to the same conclusion as Johnson (1996:10): "there ought to be some connection between what a group claims to be, and the way it does things". In other words, I became aware of the importance of intentionally integrating spirituality into decision-making processes.

In this article, the term "spirituality" refers to the relationship between God and human beings, which is formed in everyday life through an interplay of human and divine activity (Waaijman 2002:426). The human side of this activity are spiritual practices, which have the function that the human being exposes him-/herself consciously to the working of God.

In decision-making processes within the context of Christian churches, the resource of spirituality is too often neglected or used only as an undefined appendage. This problem has also been recognised in The Salvation Army. Although The Salvation Army has always been committed to faith in all its activities, sociological theory and management techniques have often had the last word when it came to decision-making (Hill 2017:123).3 However, not only the secular approaches have proven inadequate in Salvation Army practice. In addition, the hierarchical structure of The Salvation Army, which manifested itself in a "command-and-control" method, has turned out to be increasingly inappropriate.4 Therefore, towards the end of the first decade of the 21st century, voices were expressing concern that secular techniques were overrated and theological resources simultaneously neglected (Pallant 2012:171-172; Cameron 2012:1-2). In response, the "Faith-Based Facilitation" (FBF) process, based on the pastoral circle (Cameron 2012:1-2; Pallant 2012:173), was developed and introduced in 2010 (The Salvation Army International Headquarters 2010).

The process is currently used in decision-making processes, project and church evaluations and as a means for structuring ethical discussions. As a methodology that integrates theory and practice as well as spirituality, the FBF process can also make a contribution to theological education.

A characteristic of the FBF process is the concept of the 'Kairos experiences'5 as a key spiritual aspect. In the already sparse literature on the FBF process, hardly anything has been written about the nature of the "Kairos experiences", even though great emphasis is placed thereon. Thus, the problem arises as to how to deal with this phenomenon in practice. The purpose of this article is, therefore, to provide methodological aids in dealing with the "Kairos experiences".

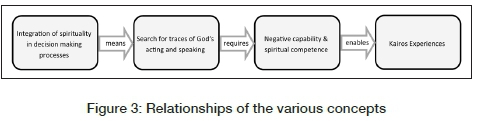

Towards that end, I will first introduce the process as such before exploring the concept of the 'Kairos experiences'. Then I will argue that the development of the disposition and spiritual competence as educational aspects are key to the integration of spirituality in decision-making and evaluation processes. I will show that the regular practice of spiritual exercises in a group is the prerequisite for a successful integration of spirituality in decision-making processes. Lastly, I will provide a brief overview of the integration of spirituality in the practice of the FBF process.

2. THE FAITH-BASED FACILITATION PROCESS6

As mentioned earlier, the development of the FBF process emanated from the need to integrate Christian faith as a crucial factor in the work of The Salvation Army, or, as the booklet Building deeper relationships puts it, "Faith-Based Facilitation helps people connect their faith with their actions" (The Salvation Army International Headquarters 2010:4). This is also reflected in Pallant's (2012:173) definition:

Faith-Based Facilitation [is] a process and set of tools which helps, encourages, and enables people to speak and, in the light of Biblical truths, make more faithful decisions and enjoy deeper relationships. An intentional searching for spiritual insight (called 'Kairos Experience') is central to Faith-Based Facilitation. A facilitator does not only have skills and tools, s/he seeks a Christ-like character.

The FBF process begins by clearly identifying the issue to be decided. Then comes the phase of description and analysis of the situation, in which the experience was made or in which the issue is embedded. The third phase is devoted to theological reflection. Based on the results of the previous steps, the actual decision is made, and measures are planned in the subsequent phase. Finally, the last step involves the execution of the planned action.

As far as the individual steps are concerned, the FBF process is similar to the pastoral circle that emerged from the Latin American liberation theology7 and was made known through Holland and Henriot's publications. This circle includes the steps "insertion", "social analysis", "theological reflection" and "pastoral planning" (Holland & Henriot 1983:7-8).

The most striking difference between the FBF process and the pastoral circle, however, is the concept of the "Kairos experiences", which is not assigned to any specific phase of the process, but placed in the middle of the diagram below. Before I turn to these "Kairos experiences", it should be noted that the circle below is not completed with the "Act" phase, but it moves into a new round. The decision and thus the action influence the situation, which can then be evaluated again by using the FBF process.

3. KAIROS EXPERIENCES

The development of the FBF process arose from the need to promote theologically informed practice in the work of The Salvation Army. This was based on the observation that previous methods placed too much trust in the human ability to solve problems on our own (Pallant 2012:172). According to The Salvation Army officer and theologian Dean Pallant (2012:173), who initiated the development of the FBF, the influence of the Bible and the work of the Holy Spirit, as manifested in the "Kairos experiences", are key to the process. What is meant by "Kairos experiences"?

3.1 The nature of the Kairos experiences

The Greek word kairos can be translated as "'the right' or 'special time'" (Sipiora 2002:119) or "the decisive moment or time" (Delling 1935:457). This literal sense can be well illustrated with replicas of the lost Kairos statue of Lysipp: A naked youth scurries past on tiptoes. He wears a forelock as his hairstyle, the hair at the back of his head is shorn short. The lock of hair symbolically indicates that one must seize the opportunity. The American philosopher John Smith called "kairos" "the time of opportunity or 'occasion'" (Smith 1969:6). The concept is based on the idea that "there are constellations of events pregnant with a possibility (or possibilities) not to be met with at other times and under different circumstances" (Smith 2002:47). The American theologian Elizabeth Conde-Frazier (2014:240-241) contributes a further aspect. For her, "kairos" is the place "where the Spirit of God is mediating and intervening in life and we participate in this action". "Kairos" is not only a "flash of inspiration", a "eureka moment", but discovering where God is speaking and acting, and, in consequence, participation in it. New Testament examples of this notion can be found in Titus 1:3 and Galatians 6:9, among others. The "Kairos experiences" are thus about discerning traces of God's speaking and acting.

The fact that the "Kairos experiences" play a role in the FBF process at every stage is, therefore, important. In each phase, traces of God's action and speech can be expected and discerned. Some of these aspects will be shown for each phase of the process.

3.2 The Kairos experiences and the individual phases of the process

In the first two steps of the FBF cycle, the group participating in a decision-making or evaluation process establishes the "place" of the group. I understand "place" not only geographically, but with Sheldrake (2001:1) as the "dialectical relationship between environment and human narrative". In this article, "place" refers to the group's own perceived, current situation, to which meaning is assigned through shared experience and history, as Brueggemann (2002:4) indicates:9

Place is space that has historical meanings, where some things have happened that are now remembered and that provide continuity and identity across generations. Place is space in which important words have been spoken that have established identity, defined vocation, and envisioned destiny. Place is space in which vows have been exchanged, promises have been made, and demands have been issued.

Narrated, shared, common history defines the perceived present, the present place and gives it meaning. Sheldrake (2001:17) concludes that "there can be no sense of place without narrative". The establishing of a place can also be shaped by common rituals or spiritual exercises practised together.

Thus, "place" becomes a condensed, meaningful present. It points beyond itself (Sheldrake 2001:30); it calls for change. It challenges one not to remain attached to the history of the group, but to continue writing history. In these two phases, it is, therefore, a matter of discerning the golden thread of God's history (i.e. the traces of God's speaking and acting in the history of the group) and of trying to extrapolate this golden thread into the future.

At this point, the third phase comes into play: theological reflection. In his lecture Der Begriff der Zeit, Heidegger (2004:107) wrote: "If time finds its meaning in eternity, then it must be understood [as] starting from eternity." Or to say it with Tillich (1967:370):

The relation of the one kairos to the kairoi is the relation of the criterion to that which stands under the criterion and the relation of the source of power to that which is nourished by the source of power.

Every (little) "Kairos experience" must be put into the context of the great Kairos (and by this, Tillich means Jesus and his work of redemption). This is done by confronting the findings from the "search for traces" in the first two phases with the Word of God. In the present, the past is, so to speak, brought into conversation with the future or eternity. The story of the group is interwoven with the story of the Bible.

In phase 4, the decision is made in view of the yields from the "search for traces" of the first three steps. In this phase, the participants give space to spirituality by working with so-called Anhörrunden ("listening sessions"), alternating with personal reflection times. "Listening sessions" are group discussions, in which each participant brings his/her contribution to the group without commenting on it. Between the individual statements, a moment of silence allows the participants to appreciate what has been said. The personal time of silence offers the opportunity to listen to God in prayer.

After an attempt has been made in the first four phases to arrive at a good decision, the step "Act" brings about the phase of "getting involved in what is happening", as the German theologian Andreas Wollbold (1999:184) describes the term "Kairos". This step is not about enforcing one's own planning; it is about creating common experiences by means of reflection on the insights attained when arriving at new orientations. In this phase, the "Kairos experiences" are thus experienced by reflecting on the facts created by action.

At the moment of the decision-making process (or evaluation), the past and the future meet, so to speak. Both in the past (i.e. in the common narrative) and in the future (represented, in this instance, by biblical texts that bring the perspective of eternity into the present), a search for traces takes place. This discovery of the traces of God's speaking and acting are the "Kairos experiences". They are, however, unforeseen revelations of God; they cannot be predicted or controlled (Cameron 2012:6). They are not to be brought forth; they are received. Therefore, space must be created in the process to discern the "Kairos experiences" as such.

4. PREREQUISITES FOR THE SUCCESSFUL INTEGRATION OF SPIRITUALITY

To create space for the discernment of the "Kairos experiences", two educational aspects are involved as prerequisites for the success of the FBF process, namely the development of a certain disposition and the spiritual competence of the group.

4.1 Negative capability

The disposition to be developed by those involved in the process is openness to the "Kairos experiences". The nature of this openness can best be described with the concept "negative capability". This term, coined by the English poet John Keats (1899:277), describes the willingness to accept uncertainty and to let go of long held assumptions and opinions without frantically asking for facts and reason.

Simpson and French (2016:245) point out that

such thinking requires the capacity to see what is actually going on, in contrast with what was planned for, expected or intended - even when what is actually going on is uncertain or even unknown.

This attitude enables openness and receptiveness to God's speaking and acting, which can be noticed in the golden thread of past experiences and in the events of the present moment. "Negative capability" has a strong creative element (Bate 1939:21-22), which does not try to classify what is perceived into predetermined categories (and thereby often distort it), but allows that, through recognition, something new is created. New things can emerge when people, in the process of making decisions, are able to wait, observe and investigate experiences (Lombaard 2017:112), until they discover the hidden movement and intention behind it (Bate 1939:21), until the pattern under the outer surface emerges (Simpson et al. 2017:1212).

In decision-making processes, those involved are always confronted with the uncertainty of the future. If, in such situations, the group succeeds in not seeking refuge in immediate (re)actions, but rather succeeds in dwelling in the moment, observing and listening, God creates space for new thoughts and perspectives to emerge. Letting go of plans already made and being open to the emergence of something new are the keys and the prerequisites for integrating spirituality into the process of decision-making.

4.2 Spiritual competence

Spiritual competence, according to the Berlin Model (Nikolova et al. 2007:72), is understood as competence in the interpretation of, and participation in spiritual experiences. Interpretative competence means being able to perceive spiritual experiences such as the "Kairos experiences", and to interpret them appropriately. Participation competence, in turn, means being able to engage oneself with one's own and other people's spiritual experiences and to communicate them. The spiritual competence of the group and its participants, who go through the process of decision-making, is a basic prerequisite for discerning the "Kairos experiences" and dealing with these experiences in a fruitful way.

The aforementioned disposition and spiritual competence cannot be developed only individually. What I would like to call "spiritual team development" can and should also be practised as a group. With this, I would like to emphasise that it does not suffice to carry out the FBF process in a methodologically flawless way. A longer term learning process is required, namely spiritual team development. Spiritual team development means the regular practice of spiritual exercises in the group, the practice of searching for traces (in the form of interim evaluations), and listening sessions, even when no major decisions or evaluations are pending. In this way, a certain competence can be reached within the group, so that when the group has to make decisions later, it does so as a spiritually more experienced group.

Figure 3 shows the relationships between the concepts described earlier.

5. EXPERIENCES WITH THE FBF PROCESS

The two major evaluations of the FBF process, conducted by Olivier (2012:22) and Farrell (2016:18), respectively, revealed that, for those who employ this process, the component of spirituality is the most significant difference to other methods used thus far. However, this does not mean that spirituality plays a major role for all who make use of the FBF process in practice. In other words, the vast majority of individuals consider spirituality to be very important, but it is nevertheless rarely integrated into practice. Olivier (2012:23) concludes in her report that the process was conducted only infrequently, as described in the booklet Building deeper relationships (The Salvation Army International Headquarters 2010), and that those who followed the cycle did not report any specifically spiritual elements. Only a small percentage of those surveyed by Farrell (2016:67) mentioned spiritual elements such as meditation on Bible texts or "Kairos experiences", as "tools" in their process. Both authors observed that, in the region they studied, users found it difficult to combine spirituality and practice (Olivier 2012:18; Farrell 2016:41).

One reason for this difficulty is that the existing training materials on the FBF process are insufficient, and fundamental theological texts are, therefore, not available. This is a finding in both aforementioned evaluations. The booklet Building deeper relationships was the only resource available. It is more a description of the process than a real training manual (Farrell 2016:48). Furthermore, the current case studies on the FBF homepage were not sufficient and have to be supplemented (Olivier 2012:6).11 It was, therefore, recommended that a resource be developed specifically to facilitate theological reflection (Olivier 2012:5-6). The New Zealand Salvation Army officer and theologian Harold Hill (2017:123) touches a sore spot by observing that the elements of spirituality in the FBF process are perceived by people employing the FBF process only as supporting functions that can be omitted, if necessary. These findings support the importance of the spiritual team development mentioned in section 4.2 above.

Notwithstanding the difficulties identified by the evaluations, Farrell (2016:76) also mentions the effects of a spiritual nature in communities and churches:

The 'faith' component of FBF is undeniably powerful in that it positions the approach in such a way that (if implemented correctly) participants engaged with it are exposed to the nurturing and all-embracing nature of spirituality.

6. CONCLUSION

In summary, the FBF process provides The Salvation Army's staff with a valuable method for integrating spirituality into decision-making. However, it could justly be stated that simply creating a new tool does not change organisational culture. The old way of making quick decisions without following a conscious process - and thus lacking discernment - often prevails. It is, therefore, essential that great importance be placed on the integration of spiritual elements in the group's day-to-day business and the regular promotion of the group's spiritual competence, so that spirituality becomes an integral part of the decision-making process in the long term and can have a positive effect as a beneficial resource.

The integration of spirituality in decision-making processes rests on two pillars, namely the intentional integration of spiritual elements (periods of reflection in prayer, meditation on Bible texts, and so on) and the development of the group's approach towards spirituality (negative capability, spiritual competence). Without these two pillars, the methodological elements cannot develop their full power.

It is hoped that, in The Salvation Army and beyond, decision-making processes will increasingly become spiritual processes, in which spiritual practices not only serve as an appendage (which can be left out when time is short), but also as integral supporting elements.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bate, W.J. 1939. Negative capability: The intuitive approach in Keats. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 2002. The land: Place as gift, promise, and challenge in biblical faith. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Cameron, H. 2012. Theological reflection: Reflections on the challenges of using the pastoral cycle in a faith-based organisation. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.biapt.org.uk/documents/HelenCameronSS12.pdf [14 July 2018]. [ Links ]

Conde-Frazier, E. 2014. Participatory action research. In: B.J. Miller-McLemore (ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell companion to practical theology (Malden,MA: Wiley-Blackwell), pp. 234-242. [ Links ]

Delling, O. 1935. Kaipóç. In: G. Kittel (ed.), Theologisches Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testament (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer), pp. 456-465. [ Links ]

Farrell, S. 2016. Capacity building and development through faith based facilitation (FBF) - Africa Zone. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://norad.no/globalassets/publikasjoner/publikasjoner-2016/ngo-gjennomganger/capacity-building-through-faith-based-facilitation-fbf--africa-zone.pdf [1 October 2020]. [ Links ]

Freire, P. 2005. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. 2004. Der Begriff der Zeit. Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann. Gesamtausgabe 64. [ Links ]

Hill, H. 2017. Saved to save and saved to serve: Perspectives on Salvation Army history. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock. [ Links ]

Holland, J. & Henriot, P. 1983. Social analysis: Linking faith and justice. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Johnson, LT. 1996. Scripture and discernment: Decision-making in the church. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Keats, J. 1899. The complete poetical works and letters of John Keats. Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press. [ Links ]

Kessler, v., Knecht, S. & Marsch, A. 2021. Integrating spirituality into decision-making: Case studies on international faith-based organisations. In: M. Cristofaro (ed.), Emotion, cognition and their marvellous interplay in managerial decision aking (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), pp.186-208. [ Links ]

Knecht, S. 2020. Die Rolle der Spiritualität in Entscheidungsfindungsprozessen: Der "Faith-Based Facilitation"-Prozess der Heilsarmee. Unpublished Masters' dissertation. Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2017. Leadership as spirituality en route: "Negative capability" for leadership in diversity. In: V. Kessler, S.C. van den Heuvel & J. Barentsen (eds), Increasing diversity: Loss of control or adaptive identity construction? (Leuven: Peeters, Christian Perspectives on Leadership and Social Ethics 5), pp. 103-114. [ Links ]

Nikolova, R., Schluss, H., Weiss, T. & Willems, J. 2007. Das Berliner Modell religiöser Kompetenz: Fachspezifisch - Testbar -Anschlussfähig. Zeitschrift für Religionspädagogik 6(2):67-87. [ Links ]

Olivier, J. 2012. Review and evaluation of the Salvation Army's Asia-Pacific Regional Facilitation Team Project. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://norad.no/globalassets/import-2162015-80434-am/www.norad.no-ny/filarkiv/ngo-evaluations/review-and-evaluation-of-the-salvation-armys-asia-pacific-regional-facilitation-team-project.pdf [1 October 2020]. [ Links ]

Pallant, D. 2012. Keeping faith in faith-based organizations: A practical theology of Salvation Army Health Ministry. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock. [ Links ]

Sheldrake, P. 2001. Spaces for the sacred: Place, memory and identity. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Simpson, P. & French, R. 2016. Negative capability and the capacity to think in the present moment: Some implications for leadership practice. Leadership 2(2):245-255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715006062937 [ Links ]

Simpson, P., French, R. & Harvey, CE. 2017. Leadership and negative capability. Human Relations 55(10):1209-1226. https://doi.org/10.1177/a028081 [ Links ]

Sipiora, P. 2002. Kairos: The rhetoric of time and timing in the New Testament. In: P. Sipiora & J.S. Baumlin (eds), Rhetoric and Kairos: Essays in history, theory, and praxis (New York: State University of New York Press), pp. 114-127. [ Links ]

Smith, J.E. 1969. Time, times, and the "right time": Chronos and Kairos. The Monist 53(1):1-13. https://doi.org/10.5840/monist196953115 [ Links ]

Smith, J.E. 2002. Time and qualitative time. In: P. Sipiora & J.S. Baumlin (eds), Rhetoric and Kairos: Essays in history, theory, and praxis (New York: State University of New York Press), pp. 46-57. [ Links ]

The Salvation Army International Headquarters 2010. Building deeper relationships: Using faith-based facilitation. London: The Salvation Army. [ Links ]

Tillich, P. 1967. Systematic theology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Waaijman, K. 2002. Spirituality: Forms, foundations, methods. Leuven: Peeters. [ Links ]

Wollbold, A. 1999. "Von der Linie zum Fleck": Pastoraltheologie als Hilfe zur Entscheidungsfindung. Zeitschrift für katholische Theologie 121(2):177-191. [ Links ]

Date received: 24 October 2021

Date accepted: 03 June 2021

Date published: 14 June 2021

1 This article develops further insights from a University of South Africa Masters dissertation titled Die Rolle der Spiritualität in Entscheidungsfindungsprozessen: Der "Faith-Based Facilitation"-Prozess der Heilsarmee.

2 The Salvation Army, established in 1865, is a Christian church and international charitable organisation with a worldwide membership of over 1.8 million people.

3 Management techniques and insights are undoubtedly also a great help for churches. But this aspect is often overemphasised, especially in decision-making processes, at the expense of spirituality.

4 Dean Pallant, e-mail to Knecht, 29 March 2020.

5 In this article, I do not use the concept "kairos" as it relates to the South African Kairos Document, but more in relation to its New Testament meaning.

6 For more information about the development, application and impact of the FBF process, see Kessler et al. (2021:194-199).

7 See, for example, Freire (2005:51, 65) and his concept of "praxis", which describes the close connection between reflection and action.

8 The author's drawing. The original is from The Salvation Army Headquarters (2010:6).

9 With this, I follow the argumentation of Sheldrake (2001:7), who also quotes Brueggemann.

10 The author's drawing.

11 Olivier suggested this in 2012. At present, the home page still presents itself unchanged. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.salvationarmy.org/fbf/casestudies [16 March 2020].