Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.41 suppl.31 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup31.11

ARTICLES

A plea for leadership theories

V. Kessler

Prof. V. Kessler, GBFE, Gummersbach, Germany; Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology, University of South Africa, Pretoria. E-mail: volker.kessler@gbfe.eu; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8420-4566

ABSTRACT

This article addresses the challenge of teaching theory to people who view theorising sceptically. This is often the case in the context of leadership trainings. In this article, I critically analyse the trivialisation of leadership, often based on success stories, and offer seven methods to include theory in leadership classes, namely electing students; reversing the order: practice-theory instead of theory-practice; creating aha experiences with theory; selecting "good" theory; pointing out the benefit of a special theory; viewing theories as eye-glasses, and suggesting eyeglasses from different disciplines. I then argue, first, that leadership theory is needed, because real leadership is nontrivial and, secondly, that we need to teach more than one leadership theory, in order to encourage critical thinking.

Keywords: Leadership education, Trivialisation of leadership, Aha-experiences, Theory-practice-cycle

Trefwoorde: Leierskap onderrig, Leierskap trivialisasie, Aha-ervaing, Teorie-praktyk-siklus

Dedicated to my friend and colleague Louise Kretzschmar, Unisa, on the occasion of her 65th birthday. Her life models the successful integration of theory and practice.

1. INTRODUCTION

This article discusses the challenge of teaching theory to people who do not like theory, as is often the case in the context of leadership education and training. Since leaders have to make decisions in real time, they often lack the time for the lengthy discourses that are typical of the ivory tower of academics. Foundational work is viewed as time-consuming, as noted by the leadership professor Heifetz (1998:7): "Practitioners have little patience for ideas that fail to speak to real experience."

This article is derived from our experience with the Akademie für christliche Führungskräfte (Academy of Christian Leadership),1 a college within the Gesellschaft für Bildung und Forschung in Europa (GBFE) (Association for Education and Research in Europe), a network of 13 colleges in Europe.2 The academy has been teaching leadership on masters level since 1999. I also teach leadership at various international universities and seminars, as well as at one-day seminars in business and non-profit organisations.

I start the article with some critical observations on the current market of leadership guides. Then I suggest seven methods for teaching theory in leadership classes, which are based on my 20 years' experience in teaching leadership. This section is a kind of practitioner's report. Finally, I argue for the need to teach leadership theories to students. Many thanks to my colleagues Stefan Jung from YMCA-University, Germany, Bernhard Ott from GBFE, Switzerland, and Jack Barentsen from ETF Leuven, Belgium, for their input on this article.

2. SOME NOTES ON CURRENT LEADERSHIP GUIDES

2.1 "Leaders do not like theory"

The statement "leaders do not like theory" might be slightly too harsh and too simplistic. Of course, theory and practice have different goals. Professors want to explain the world, and practitioners want to shape the world. Top leaders have to take many decisions daily under enormous time pressure. They need solutions immediately. There is also a personality aspect, because leaders are often men and women of action who view theory with scepticism. In class, the teacher may experience this attitude as a lack of interest in theory. Some leaders would even frankly state: "I do not like theory."

This is not a new phenomenon. Already in the 1950s, the famous leadership expert Douglas McGregor was confronted with this attitude. He invented the so-called Theories X and Y, which have become fundamental in leadership studies. His famous book The human side of enterprise starts with 58 pages on theory, "The theoretical assumptions of management" (McGregor 1985:1-57). Obviously, McGregor saw a need to defend his decision to start with theory. He gives a few reasons why the managers of his time were relatively slow in using knowledge from the social sciences.

The first is that every manager quite naturally considers himself his own social scientist. His personal experience with people from childhood on has been so rich that he feels little real need to turn elsewhere for knowledge of human behaviour. The social scientist's knowledge of human behaviour often appears to him to be theoretical whereas his own experience-based knowledge is practical and useful (McGregor 1985:6).

McGregor (1985:6) then argues that "theory and practice are inseparable", because our assumptions "determine our predictions that if we do a, b will occur". McGregor (1985:7) thus criticises the rejection of theory as follows:

It is possible to have more or less adequate theoretical assumptions; it is not possible to reach a managerial decision or take a managerial action uninfluenced by assumptions, whether adequate or not. The insistence on being practical really means, "Let's accept my theoretical assumptions without argument or test.".

Sixty years later, the situation is similar in that theory is not highly appreciated in leadership or management training.

2.2 Cultural influence: "Principles-first or applications-first"?

This negative attitude towards theory may have cultural roots. Leadership is a hot topic in the USA. Frederick Taylor's The principles of scientific management (1911) was the first book on management to be published in the USA (Crainer 1997:279). Since then the overwhelming majority of leadership books have been published by American authors (Crainer 1997:7-11). The MBA concept has become a typical postgraduate study for business leaders worldwide and originated in the USA in the early 20th century. There is indisputably a strong USA impact on the topic of leadership that influences the style of writing.

Erin Meyer, who was born in the USA and now teaches and lives in Paris, is known as an expert on intercultural leadership. In her successful book The cultural map, she distinguishes between two styles of reasoning and persuading, principles-first and applications-first (Meyer 2014:93). Meyer uses business stories from Germany and America to illustrate these two different styles. She quotes a German director as saying: "In Germany, we try to understand the theoretical concept before adapting it to the practical situation" (Meyer 2014:92). This attitude can also be noticed in the German educational system. Classical German universities, following the Humboldt model, are known for their strong focus on theory, and this has implications for their teaching method (see section 3.2).3 According to Meyer's (2014:96) figures, France is even more principles oriented than Germany.4

Compared to European cultures, the American culture is fairly pragmatic, and this attitude has become typical of their writings on leadership. One could, of course, also argue that leadership is so well developed in the USA because of their cultural preference for applications. In any case, popular leadership books and applications-first seem to go hand in hand.

By no means should this note on the cultural influence on leadership give the impression that American books would never contain leadership theory. On the contrary, there are excellent books on leadership theory written by American authors. I already mentioned McGregor and his desire to lay a theoretical foundation for leadership. The American author Heifetz (1998:8) wrote his book Leadership without easy answers with the declared goal of "theory-building". Northouse's volume Leadership: Theory and practice (2018) is one of the best handbooks on leadership theory. Although there are excellent American books on leadership theory, it is also true that, currently, the vast majority of popular leadership guides are application driven.

2.3 Trivialisation of leadership

Often, a leadership seminar or leadership book consists of storytelling, a few personal anecdotes with no connection to any theory at all. The recipe is simple:5 first, one identifies successful leaders such as Bill Gates (Chandomba 2019) or Jeff Bezos (Stone 2014). Secondly, one seeks the secrets of their success. Thirdly, their practices are given the status of benchmarks. The bookshops at airports abound in these books. Famous CEOs have become the heroes of our time, and their popular biographies resemble the art of hagiography of former times (Neuberger 2002:27).

Of course, these success stories have their place. They are interesting case studies and should be regarded as such. Case studies have their values but also their limitations with respect to transferability. For example, people might be fascinated by a famous CEO and try to apply his/her methods to a church or another non-profit organisation, not taking into account that different types of organisations might require different leadership skills. As early as 1961, the sociologist Etzioni6 (1964:59-67) identified three different types of organisations, classified by means of control. These can be coercive power (for example, jailhouses), utilitarian power (for example, business companies), or normative power (for example, churches, political parties). The power bases of a director of a jailhouse differ from those of a leader in a company or a pastor in a church.7 The fact that a person is doing well with a specific set of power bases does not necessarily imply that s/he can also cope with a different set of power bases. Etzioni (1964:61) thus concluded that "a person who is a leader in one field is not necessarily a leader in another".

Sixty years later, this basic fact is still ignored. When churches seek capable volunteers for church eldership, they often seek successful business leaders. They expect that a successful business leader will automatically be a good church leader, provided that s/he is committed to the church.

The leadership of an organisation must consider the characteristics of that organisation. Leaders should know something about the sociology of organisations.

2.4 Social systems are non-trivial

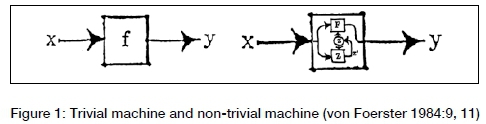

Leadership always happens in a context. As a rule, leadership is a process within an organisation. Organisations are social systems that communicate decisions (Nassehi 2005; Luhmann 2011b:63). One of the fathers of cybernetics, the Austrian-American Heinz von Foerster (1911-2002), was once invited to give a talk on "management and self-organisation in social systems". He introduced a distinction that became fairly famous, trivial machines and non-trivial machines (von Foerster 1984:9-13).8

In a trivial machine, the same input x will always lead to the same output y=F(x). In our daily lives, we rely considerably on the predictability of trivial machines. When we press the button on the coffee maker, we expect to get the chosen coffee. When we use an ATM, we expect to receive money according to the number we entered. We get nervous or sometimes angry in those instances when these "machines" do not give the expected output. The term "machine" is not restricted to physical machines; it is an abstract term for any transformation calculus.9 Like any other advice literature, popular management literature regards social life and leadership as a trivial machine. If the leader does x, then y will happen.

A non-trivial machine has a second machine inside it, representing the inner state of the machine, its "history". As a result, the input x may lead to the expected output y, but it may also lead to different outputs y', y", and so on, depending on the inner state of the machine. The inner feedback loop creates a new level of complexity, and thus the output of a non-trivial machine is "unpredictable" (von Foerster 1984:13). Von Foerster and other system theorists such as Luhmann (2011a:95) are convinced that social systems behave like non-trivial machines. Social systems might act as trivial machines for many days, but suddenly show their non-trivial character.

Trivialisations are popular and they serve a market, because "we want trivial machines" (von Foerster 1984:13). Trivialisations keep the book market going. For example, a manager buys a book or listens to a well-paid speaker on management who proclaims that if you do x, then y will happen in your company. The manager will try x, but will be disappointed, because the output might be y', different from the expected output y. The manager will be frustrated and again seek a good solution. He might buy another book for the latest insight that if you do z, then y will finally happen, and so on. Thus, each year there is a new need for advice literature.

Another example is recipes for diets. No recipe is really successful, and this failure keeps the market for diets going strong. As in management, one is always keen to learn from the latest success story, and then one is disappointed, because it does not work out in one's own context.

3. SOME METHODS TO INTEGRATE THEORY IN LEADERSHIP CLASSES

As an academic scholar, I face the following dilemma: I am convinced that leadership theory is necessary, but I also know that many participants in my classes are prejudiced against theory. How can we solve this dilemma?

Before describing the methods, I must state that these methods are application driven. I do not want to fall into the same trap that I described earlier. Therefore, I do not claim to have found the ultimate key. The following is a practitioner's reflection, which at best might serve as an interesting case study. By no means do I claim to present a reference model for leadership education.

3.1 Selection of students: Only students with experience

At the Academy of Christian Leadership, we require that students have some real-life experience. We do not accept students who have recently obtained their bachelor's degree and only know university life. The reason is simply that the students should have experienced failure in exercising leadership. From a purely theoretical perspective, leadership appears to be trivial and easy: if you do x, then y will happen. Failure shows the students that leadership is not that easy; then they become more open to non-trivial explanations.

Another advantage of this requirement is that the students can bring their real problems, as is explained in the next paragraph.

3.2 Reverse the order: practice-theory instead of theory-practice

In my experience, people become interested in theories as soon as they perceive some benefit in them. As the above quote from the German director shows, traditional German education starts with theory, sometimes even with a discourse on meta-theory. This is then followed with a discussion on applications.10 At our academy, we often use the reverse order. For example, in our seminar on conflict management, the participants can bring their own case studies of conflict, in which they are currently involved. Once this conflict is in the spotlight, we introduce a theory that might help understand the conflict better and/or offer steps to manage the conflict. The order is first practical examples, then theory applied to the examples given, instead of theory first and examples afterwards.

By doing so, we follow models suggested in Contextual Theology and modern Practical Theology. For example, Green (2009:39) recommends starting with experience before proceeding to explore, reflect and respond.

Similarly, the American practical theologian Richard Osmer (2008:4) identifies four questions and four tasks.11 He argues that leaders should ask the following four questions in response to difficult situations: What is going on? Why is this going on? What ought to be going on? How might we respond? According to Osmer (2008:4), these questions correspond to four core tasks of practical theological interpretation: the descriptive-empirical task; the interpretative task; the normative task, and the pragmatic task.

Like Green, Osmer starts with experience. He follows the order "practice-theory-practice" of his teacher Dan Browning (Osmer 2008:148). Osmer splits the middle term "theory" into two parts, the search for a good theory to understand and explain the situation better, and the search for ethical guidelines in this situation.

I now return to the seminar on conflict management. By introducing a theory that fits the given conflict case, we work on the interpretative task.

Theories help us understand and explain certain features of an episode, situation, or context but never provide a complete picture of the 'territory' (Osmer 2008:80).

Leaders and teachers need wisdom to apply the theory adequately.

Our personal experience is that students receive theories well if these theories are offered at the right moment. Students discover the value of a theory if it can be successfully applied to real problems.

3.3 Creating aha experiences based on theory

The term "aha experience" goes back to the German psychologist Karl Bühler (1879-1963). It means "the sudden appearance of a solution through insight" (Topolinski & Reber 2010:402). It describes a spontaneous comprehension, meaning the moment when a previously unsolvable puzzle suddenly becomes clear. According to Piper (1981:47), the aha experience denotes the step between wondering and understanding.12 Piper links the aha experience with the learner's practical experience. I would argue that insight from theory can also stimulate an aha experience. Ott (2013:52) also covers this by regarding aha experiences as crucial in education:

The key experience here is the aha-experience, the moment at which there is an understanding, at which the theory is grasped in a way that illuminates practice.13

For example, in my leadership classes, I would speak about von Foerster's distinction between trivial machines and non-trivial machines, with some practical examples. Often, at the end of the course, when asked: "What do you take away from this course?", some students will mention the non-trivial machine as an eye-opener, as an aha experience.

3.4 Careful selection of "good" theory

I try to avoid presenting too many theories, although some students probably still think that there is too much theory in my leadership classes (see section 3.8). I would not present theory for the sake of theory, but I do support Lewin's maxim that "nothing as practical as a good theory".14 The question is: When is a theory "good"?

Lehner (2020:149) describes the tension between practitioners who would damn all theory and academics who would regard each theory as highly important and relevant. Lehner then argues that there are theories that can be practical.15 Whether they are of practical use depends on the context.

I call a theory "good" if it

a) fits the given context and situation of the problem;

b) offers explanations for observed phenomena, creating aha experiences, and/or

c) gives ideas for future actions.

It is the duty of a teacher to select the good theories. As a rule, I try to find theories that fulfil a), b) and c). But this is not always possible; for example, Luhmann's system theory is good at b), but it hardly offers anything in c), as explained in the next section.

3.5 Pointing out the benefit of a special theory

Some years ago, I started to include Luhmann's system theory in my leadership classes.16 Niklas Luhmann (1927-1998) was a German professor of sociology, whose publications are brilliant, but highly theoretical. He has his own definitions of "system", "communication", and so on. One needs some time to understand his writings.

Luhmann's system theory helped me understand some of the leadership challenges we face in the real world. It offers explanations for phenomena which I observed but for which I had no explanation. For example, Luhmann's concept of autopoiesis explains why organisations still survive, although they do not meet any of the objectives for which they were founded. My justification for taking time for Luhmann in my classes is that I could not find any other theory offering an explanation as convincing as his.

Reading Luhmann can become frustrating. When I introduce his theory to the students, I use the metaphor of mountain hiking. It takes time and effort to get to the top of the mountain, but once you reach the top and enjoy the view from there, you know it was worth every drop of sweat. It takes some effort to get into Luhmann's theory, but the applications drawn from this theory offer so much insight that many students seem to enjoy it. At least, this is what some mention in the feedback at the end of the course.

This example shows that one needs time to expound theory. In Luhmann's case, one needs at least one hour to explain the foundations -and that is very concise - before one gets to the practical examples. Thus, this approach does not work in a context where the teacher does not have sufficient time.

3.6 Viewing theories as eye-glasses

Often, people hope to find a leadership theory that works. This theory then becomes an authoritative model for how to lead. This often causes disappointment when students discover that the model does not work in practice. This use of theory is another example of trivialisation (see Figure 1), because one views a theory as an input x and hopes to receive the output y.

Theories should rather be regarded as eye-glasses, as stated by Justin Reich, education specialist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT):

Theories are like eyeglasses: they bring certain dimensions of the world into sharper focus, and blur other dimensions. But if you choose the right glasses the world is - on the whole - a little clearer (Reich 2012:n.p.).

Jack Barentsen, who teaches leadership at the Evangelische Theologische Faculteit (ETF) in Louvain, Belgium, also recommends that we "regard theories as helpful lenses that highlight important aspects or dimensions of leadership that otherwise I would not know or even see".17

The metaphor of eye-glasses helps students cope with different models. In my classes, I seldom demand that the student must use this model or this theory. I prefer to explain that each model offers a different set of eyeglasses and that each pair of glasses helps us perceive different aspects of the observed data. This explanation gives the student the freedom to use or not to use a specific theory/model. One student mentioned that her personal take-away after one week of teaching was to regard strategic tools as eye-glasses.18

3.7 Suggesting eye-glasses from different disciplines

It can be fairly annoying if a teacher presents one theory after another. It becomes more interesting and creative if the theories come from different disciplines. My colleague Louise Kretzschmar and I have argued that Christian leadership is a transdisciplinary field of study that combines insights from various disciplines (Kessler & Kretzschmar 2015:3). For example, the concept of leadership has to do with power. One can view power from a sociological perspective and ask which power bases exist in which organisation (Etzioni 1964). One might also observe power with eye-glasses of psychology, and ask how one can personally deal with the power one has or the power one does not have. Finally, in the context of Christian leadership, one would like to reflect on power from a theological perspective (Kessler 2010).

Each change in perspective brings a new creative element to the discussion and keeps the student awake. The range of methods in Brassler (2020) shows that interdisciplinary teaching can be very creative.

3.8 Do these methods work?

Now that I have presented seven methods for teaching theory in leadership classes, one may ask if they work. From my teaching experience, I would state that these methods work to some extent. First, one needs time to teach theory. The methods only work in seminars that last for at least several hours. They do not work like instant coffee. Secondly, some students really like them, as can be noted from the selected feedback given earlier. In our feedback form, we regularly ask how participants would rate the amount of theory in the seminar. Most of the students respond with "appropriate". Usually, 20% will respond with "rather too much theory". Very seldom would a student answer "rather too little theory". In the long run, students who simply want to learn tools will not stay with our academy and will switch to a different kind of leadership academy.

4. WHY WE SHOULD TEACH LEADERSHIP THEORIES

In this section, I explain why teaching leadership theories is essential. The reader will notice that, by exploring this towards the end of the article, I have reversed the traditional German order described earlier. I first explained the how and will now deal with the why.

It is necessary to teach leadership theory, because leadership is not trivial: easy answers look promising, but they do not keep their promises (see section 2.4). It is even necessary to teach more than one leadership theory, because it might lead to a trivialised use of theory if students knew one theory only. The famous Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper (1902-1994) stated this brilliantly:

Whenever a theory appears to you as the only possible one, take this as a sign that you neither understood the theory nor the problem, which it was intended to solve (Popper 1972:266).

I am not sure whether Popper's statement is valid in all academic disciplines (I think that it does not apply to mathematics), but it is definitely true for the social sciences. Social sciences usually offer concurrent theories for the same phenomenon; therefore, it is good to know at least two rival theories to avoid thinking that one has arrived at the ultimate solution.

When students are able to master various theories of leadership, they are better equipped to evaluate popular leadership books. When reading a popular leadership book, the practitioner should ask questions about the hidden assumptions or the hidden theory behind this approach; act on the basis of critical thinking: The practitioner should be able to reflect on which leadership advice suits his/her context. This presupposes some knowledge of the sociology of organisations and develops their own insights about leadership.

5. CONCLUSION

Lehner (2020:151) rightly argues that theory and practice are in a "productive tension" with each other. The fact that they sometimes seem to contradict each other should not be regarded as a deficiency, but rather as a productive starting point for further reflection. Leadership education should offer a good mix of theory and practice.

It is essential to teach leadership theory, because leadership is not trivial. I suggested seven methods for including theory in leadership classes. Maybe the reader will find some of these ideas helpful in his/ her own context. If my methods do not work in your context, seek other methods, but do not neglect theory.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brassler, M. 2020. Praxishandbuch Interdisziplinäres Lehren und Lernen. 50 Methoden für die Hochschullehre. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa. [ Links ]

Chandomba, I. 2019. Secrets of success from the story of Bill Gates: It is possible. Independently published. [ Links ]

Crainer, S. 1997. Die ultimative Managementbibliothek. 50 Bücher, die Sie kennen müssen. Frankfurt: Campus. [ Links ]

Etzioni, A. 1964. Modern organizations. Englewood Cliff, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Green, I. 2009. Let's do theology. Resources for contextual theology. Completely revised new edition. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Heifetz, R.A. 1998. Leadership without easy answers. Delhi: Universal Book Traders. [ Links ]

Kessler, V. 2010. Leadership and Power. Koers 75(3):527-550. [ Links ]

Kessler, V. & Kretzschmar, I. 2015. Christian leadership as a transdisciplinary field of study. Verbum et Ecclesia 36(1), Art. #1334, http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v36i1.1334 [ Links ]

Lehner, M. 2020. Viel Stoff - wenig Zeit. 5. Aufl. Bern: Haupt. [ Links ]

Luhmann, N. 2011a. Einführung in die Systemtheorie. Hrsg von Dirk Baecker. 6. Aufl. Heidelberg: Carl Auer. [ Links ]

Luhmann, N. 2011b. Organisation und Entscheidung. 3. Aufl. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [ Links ]

McCain, K. 2016. "Nothing as practical as a good theory?" Does Lewin's maxim still have salience in the applied social sciences? Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2015.145052010077. [ Links ]

McGregor, D. 1985. The human side of enterprise. 25th anniversary printing. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Meyer, E. 2014. The cultural map. Decoding how people think, lead, and get things done across cultures. New York: Public Affairs. [ Links ]

Nassehi, A, 2005. Organizations as decision machines: Niklas Luhmann's theory of organized social systems. The Sociological Review 53(s.1.):178-191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00549.x [ Links ]

Neuberger, O. 2002. Führen und führen lassen. 6. Aufl. Stuttgart: Lucius & Lucius. [ Links ]

Northouse, P. 2018. Leadership: Theory and practice. 8th edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE. [ Links ]

Osmer, R. 2008. Practical theology - An introduction. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Ott, B. 2013. Handbuch theologische Ausbildung. Schwarzenfeld: Neufeld. [ Links ]

Piper, H.C. 1981. Kommunizieren lernen in Seelsorge und Predigt. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [ Links ]

Popper, K.R. 1972. Objective knowledge: An evolutionary approach. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Reich, J. 2012. Reich's blog on 7 May 2012. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/edtechresearcher/2012/05/all_moocs_explained_market_open_and_dewey.html. [ Links ]

Richards, L.R. & Young, R.K. 1996. Propositions on cybernetics and social transformation: Implications of von Foerster's non-trivial machine for knowledge processes. Systems Research 13(3):363-370. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1735(199609)13:3<363::AID-SRES90>3.0.CO;2-3 [ Links ]

Stone, B. 2014. The everything store: Jeff Bezos and the age of Amazon. New York: Back Bay Books. [ Links ]

Topolinski, S. & Reber, R. 2010. Gaining insight into the "Aha" experience. Current Directions in Psychological Science 19:402-405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721410388803 [ Links ]

Von Foerster, H. 1984. Principles of self-organisation - In a socio-managerial context. Originally published in H. Ulrich & G.J.B. Probst (eds), Self-organisation and management of social systems (Berlin Springer). [Online.] Retrieved from: https://cepa.info/fulltexts/1678.pdf. [ Links ]

Date received: 27 October 2020

Date accepted: 23 February 2021

Date published: 14 June 2021

1 www.acf.de

2 www.gbfe.eu

3 It is slightly different with the German Fachhochschulen (Universities of Applied Sciences) and Berufsakademien.

4 A typical argument in a German business meeting would be: "This may work in theory, but never in practice." This statement declares that practice is more important than theory. I once heard the following sentence from a French person: "This may work in practice, but never in theory." This example illustrates that theory is even more important in France than it is in Germany.

5 The steps of the recipe are described in Neuberger (2002:202).

6 In fact, Etzioni was born in Cologne, Germany. His birth name was Werner Falk. As his family had to flee the Nazi regime, he shed his German name. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amitai_Etzioni [16 October 2020].

7 For more information on power bases, see Kessler (2010:539-544).

8 Richards & Young (1996) apply von Foerster's non-trivial machine to knowledge processes.

9 By using the term "machine", von Foerster (1984:9) followed the terminology of the British mathematician Alan Turing (1936) (see the famous "Turing machine").

10 "Die chronologische Vorrangstellung der Theorie führt dazu, dass Ausbildungsprozesse mit Theorievermittlung beginnen. ... Wer etwas lernen will, muss zuerst die Theorie lernen - dann folgt die Anwendung" (Ott 2013:217).

11 It is slightly surprising that Osmer does not refer to Green's book, which was first published in 1989.

12 "Der Schritt vom Sich-Wundern zum Verstehen wird durch das sog. "Aha"-Erlebnis markiert. Ich habe verstanden! Ich habe eine Erfahrung gemacht." (Piper 1981:47).

13 German original: "Die Schlüsselerfahrung ist dabei das AHA-Erlebnis, der Moment, an dem es zum Verständnis kommt, an dem die Theorie praxiserhellend begriffen wird" (Ott 2013:252).

14 This quote is attributed to the social psychologist Kurt Lewin (1890-1947). In her analysis, McCain (2016) shows that the phrase "nothing so practical as a good theory" can be found in two Lewin-related sources and the phrase "nothing as practical as a good theory" can be found in three of Lewin's publications. Immanuel Kant or Albert Einstein is often given as a source for this statement, but there is no evidence for this (Lehner 2020:150).

15 German original: "Hier halte ich eine Existenzaussage für vertretbar: Es gibt theoretisch fundierte Konzepte, die praktisch sein können" (Lehner 2020:194f.).

16 For example, Luhmann (2011a; 2011b). For an English summary, see Nassehi (2005).

17 Personal e-mail from Jack Barentsen, 21 September 2020, as feedback to my talk.

18 Feedback on the seminar "Strategie- und Organisationsentwicklung" ECST, Korntal, 28 September-2 October 2020.