Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.41 suppl.31 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup31.3

ARTICLES

Aligning praxis of faith and theological theory in theological education through an evaluation of Christianity in South Africa

E. Oliver

Prof. E. Oliver, Department of Christian Spirituality, Church History and Missiology, University of South Africa. E-mail: olivee@unisa.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3606-1537

ABSTRACT

Having to cope in the revolution-driven world of the 21st century as well as the new-normal COVID-19 society brought theology to yet another crossroad. Theology (both theory and praxis) must react positively to the changes and lessons learned from some of the major revolutions. Just as the Fourth Industrial Revolution blurs the distinctive lines between physical, digital, and biological, so should the separated boxes of personal faith, institutionalised religion, and spirituality be wiped out. Human self-awareness helps us know ourselves and improve our ability to glorify God, while the Communication Revolution empowers Christians to spread the gospel globally. Christianity is also in need of a revolution back to its origin of an un-institutionalised, non-hierarchical, living faith that is changing the lives of people both in the present and eternally. From a South African perspective, the article evaluates the major mistakes that Christians made, some achievements on which they could build and expand, and the ideals that should pave the way forward. It is time to ask some hard questions and provide appropriate answers in the quest for Christian renewal.

Keywords: Revolution, Reformation, Effective theological education, South Africa

Trefwoorde: Revolusie, Reformasie, Effektiewe teologiese opleiding, Suid-Afrika

1. INTRODUCTION

Although we regularly - more often since the turn of the century - refer to how the world is changing at an ever-increasing rate, the extent of the global chaos we experience, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, provides a new nuance to the level and intensity of what the term "change" can entail. The pandemic is, however, not the only event causing serious transformation in our lives. Major revolutions such as the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Schwab 2016), the Fourth Communication Revolution (Warschauer & Matuchniak 2010), and the Fourth Human Self-Awareness Revolution (Floridi 2014) are also contributing to destabilising our existence.

A few broad strokes on the revolution-driven world serve as background setting for reflecting on Christianity in South Africa. This complex environment of change and transition influences our personal lived experiences, the academic side of theology as well as the theological theories underpinning these. Both the praxis of faith and the theological theories we adhere to must be altered or even "exchanged for alternatives that make more sense in the light of the totality of our experience" (Van den Toren 2016:55), as chaos and change also bring with them the inherent opportunity for growth, development, and renewal. It is beyond the scope of this study to consider theoretical aspects, but it should be noted that such aspects are also crucial and should be taken into account when new alignments are made.

After referring to some of the current major revolutions, the article briefly evaluates the failures, achievements, and ideals of Christianity in South Africa. In order for theology to stay relevant and needed in the 21st-century society (Richardson 2005), it is crucial to deliberate on the way forward (see Van der Merwe 2019). First, Christians must honestly admit to the mistakes they made, and actively reroute from these traps. Secondly, it is important to find courage and motivation amidst the current turbulent winds of change, by building on the accomplishments and successes that testify to what true and focused faith can accomplish in the face of extreme circumstances (Schmidt 2004; Hill 2005; Sunshine 2009). Asking tough questions to find appropriate answers in untraditional ways could bring new perspectives and vitality. Finally, theological education should emerge from the academic ivory towers to create flexible and adaptable spaces for theological development and living faith that can make the universal Christian ideals a reality.

Theological education must, as the example of church history clearly shows, once again embrace the technological developments of the current era to proclaim the gospel and reach the world. In line with the industrial revolution that is blurring long-existing lines, theology must obliterate the compartments that separate spirituality, institutional faith practices, and private religion, in order to once again bring faith into a ubiquitous part of human existence. Human self-awareness development must assist theologians to know themselves better, in order to act ethically and morally correct, while pursuing to glorify God and to understand our relationships better. A theological revolution or reformation, built upon a cyclical repetitive movement back to the start, will ensure that Christianity and faith once again thrive in a non-institutional-dependent, action-filled environment that will promote positive change.

2. OUR REVOLUTION-DRIVEN WORLD

Although the impact and level of change brought about by the pandemic are much more immediate and visible than the transformations we are experiencing and expecting to endure through the revolutionary events to be discussed next, theology must not only take note of these revolutions, but also ensure to interact with these developments and changes as they will definitely, to an ever-increasing extent, impact on all aspects of life. The revolutions that are currently modifying the ways in which we work, think, communicate, understand, and connect, can possibly bring immense positive outcomes, including some unexpected aspects of life such as religion and theology.

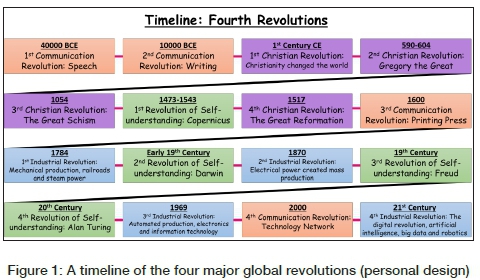

Before making a few remarks on the different revolutions that are moulding our world, I want to share a thought on how this type of history, as summarised in Figure 1, is often perceived. Shenk (2011:xi) notes that "[t]he way we understand and define the present determines how we interpret the past". Reviewing the timeline of the global revolutions, the general perception would probably be positivistic, with an emphasis on the development and prosperity that these transformations brought to mankind. This could be due to the way in which historians traditionally tend to compose their work. We learn how to judge and interpret history, in the South African context, from historical works that are prescribed for use in secondary and religious education (catechism). These works tend to focus on the dominant narrative as described by the controlling group in the different spheres of life (Lorber 2018). Kallaway (2012:55) confirms that

[u]nder apartheid education it [history] was support for apartheid, and now it seems to be support for the democratic constitution.

Denominational bias tends to provide blinkers in catechism classes that contribute to and promote disunity and fragmentation among South African Christians.

However, people should also be aware of, and encouraged to discover the less popular, hidden and often negative and traumatic other side of the story that forms part of these events. For example, the Fourth Christian Revolution (the Protestant Revolution) is generally viewed positively from a South African perspective, and seldom focuses on the bloodshed, wars, heartaches, and trauma it evoked. With time, historical lenses tend to focus more on the positive and long-term advancements of certain events, while the more personal hardship and suffering seem to be less important.

Therefore, similar to the anxieties and fears such as possible job losses, loss of income, loss of control, insecurity, stress about health implications and food security, among others, that the COVID-19 pandemic and the developing revolutions generate,1 the current chaotic circumstances will no doubt also bring some positive outcomes, progress, development, and prosperity. As with similar traumatic events, these positive aspects will, in time, most probably crystallise and become more obvious and visible when observed through historical lenses. But let us now turn to what the fourth-revolution world is currently experiencing.

By now, the term "Fourth Industrial Revolution" is part of our daily conversations and research projects. Although a number of other important revolutions2 are taking place simultaneously, we focus, in this instance, on the revolutions identified in Figure 1.

We are currently experiencing the impact of the Fourth Communication Revolution in society (Warschauer & Matuchniak 2010:179). Prior to the First Communication Revolution, people relied on gestures and repeated actions to communicate with, or to educate others. Human beings then developed language. The second major revolution came about through the development and implementation of the written text. The third revolution resulted from the use of the printing press. The Fourth Communication Revolution developed through technology-driven communication tools and changed the world into a technology-based, networking society.

The industrial revolution, in contrast to the lengthy and slow development of the communication revolutions, only started during the 18thcentury and has already reached its fourth stage. Schwab (2016) describes these major developments. During the First Industrial Revolution, water and steam power were used to mechanise production. The development of electricity ensured that the Second Industrial Revolution successfully created mass production. The Third Industrial Revolution used electronics and information technology to automate production. Building on the third,3 the Fourth Industrial Revolution refers to digital transformation that started during the middle of the last century. It is characterised by a fusion of technologies that blur the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres.

According to Floridi (2014), the human race is currently experiencing the Fourth Revolution in Self-Understanding. The first revolution of this kind was instigated by Copernicus (1473-1543), the second by Darwin (18091882), and the third by Freud (1856-1939). Floridi regards Alan Turing (19121954) as the father of the Fourth Revolution in Self-Understanding. Floridi (2014:90) argues that people no longer believe that our world is immobile or at the centre of the universe (Copernican revolution), that people are totally separated and different from the rest of the animal kingdom (Darwin revolution), and that we have Cartesian minds that are thoroughly transparent to ourselves (Freudian or neuroscientific revolution). Floridi (2014:94) concludes that

we are informational organisms (inforgs), mutually connected and embedded in an informational environment (the infosphere) which we share with other informational agents, both natural and artificial.4

Concerning Christianity, Tickle (2008:16) avers that

about every five hundred years the empowered structures of institutionalized Christianity, whatever they may be at that time, become an intolerable carapace that must be shattered in order that renewal and new growth may occur.

Tickle (2008:17) notes three effects of these renewals, namely the established form of Christianity gives birth to a new vital form; the appearance of a reconstitution of the old ossified religion, and the "new" faith spreading "dramatically into new geographic and demographic areas". She also predicted that the "Great Emergence" would be the next Christian revolution. As indicated elsewhere (Oliver 2019a), she could be wrong. The "Great Emergence" fire already burned out without making a global impact, and the 500-year periods she indicated are forced and superficial. It could be that the last revolution period in Christianity already came about with the Evangelical and Pentecostal movements. However, it is clear that Christianity has experienced some major upheavals over the past 2,000 years and it will have to adapt and change drastically once again in the current fourth-revolution world and the new-normal world of COVID-19. Although a large group of Christians are already seeking workable alternatives for the institutionalised, top-down-managed, dying form of institutionalised church, there are as yet no clear solutions or pathways on the table. Maybe a possible guideline and direction on which the search for Christian renewal could focus, is to be found in the term "revolution".

The political meaning of the term "revolution" refers to the "overthrow of an established political system" (Online Etymology Dictionary 2018). The more positive, older, and still useful meaning5 could hold a key to progress and a new way forward. Contrary to the meaning of the term that implies something new, completely different, and even disruptive from what was (Vanhoutte 2020:2), another non-political meaning of the term is used in mechanics, such as revolution counters in automobiles. This meaning is almost the complete opposite of the first meaning, as it refers back to the old French term "revolucion", which can be translated with "course" or "revolution of celestial bodies" to its original position, while the term "revolvere" can be translated with "turn or roll back". Thus, the second meaning is not understood as a break with the past, nor a fundamental change, but instead is used to indicate a "normal circling, unwinding, repetitive" movement (Vanhoutte 2020:3).

As a general, possible guideline for direction regarding the teaching of theology, both possible meanings of the term "revolution" must be applied to theological training, the church as institution, the dogmas and theological theories, as well as personal faith. On the one hand, a new path and a religious reformation are desperately needed to address the transforming environment that the church and believers are experiencing and, on the other hand, this new path should be focused on a return to the starting point, namely the fluent, enthusiastic, people-focused movement proclaiming eternal salvation as Jesus instructed and lived. The new packaging and tools should link to the time when church buildings and cathedrals (and all that is associated with these structures) were nonexistent and non-essential, in order to address the current situation, where these buildings are becoming white elephants and health risks.6 New ways of Christian living must be created, without institutionalised bureaucracy prescribing through dogma and tradition how faith should operate and be lived. The new focus must be on addressing holistic situations, neither developing theologies that only focus on addressing the temporary needs of this life, nor "pie-in-the-sky" theologies that tend to turn a blind eye to the miseries and injustices of this world. Above all, the new theology must be liquid (Joubert 2018), able to easily change form and structure to flow into and bring healing to the cracks of society and to adjust to the needs of each specific community and believer.7

By implementing these possible meanings when revolutionising Christian acts and thought to speak anew to the changing world, we can also make use of some of the positive guidelines offered by business strategists.

3. THEOLOGY AT A CROSSROAD

Although most of us are familiar with the concepts of The chaos imperative8(Brafman & Pollack 2013), and The day after tomorrow (Hinssen 2017) thinking, theologians, in general, do not take a serious interest in these business strategies, as the church or religious matters should be handled like running a business.9 However, Christians, in general, and church leaders, theological educators, and students, in particular, must ask and answer the same type of provocative questions about the church and religion that are asked about business and companies. By asking tough questions, through creating and dismantling cognitive dissonance, and by focused thinking and constructive planning, relevance can be tested, innovation can be improved, and Christianity could once again become an agent of positive change to a chaotic world. Therefore, let us reformulate some of Hinssen's (2017) questions within a theological context:

1. Why is the institutional church suffering from organisational blindness when it comes to identifying and implementing new opportunities to spread the gospel?

2. How is it possible that the institutionalised church - even when the challenges are acknowledged, and the directions that are needed to clear things up, known - is incapable of moving in the desired direction?

3. Why does the institutionalised church seem too paralysed to respond to serious issues and opportunities, while other organisations and other religions are able to respond quickly and efficiently?

4. How should the church accelerate their day after tomorrow or long-term thinking and planning regarding the concepts of theological space, justice, renewal, and so on?

5. From the work of Brafman and Pollack (2013), we can add: Where is the church's "disaster team" as well as "what-if" and "white space"10rooms - and who are currently running these spaces or allowed into these rooms? What is coming from these rooms?

These questions highlight some of the problems and challenges that put Christianity at a crossroad. The answers to these questions and the resultant actions will determine which road Christianity in South Africa will take in the next decade or two. They will also determine the fate (life or death) of some denominations. It is clear that the challenges are complex and multi-facetted and without straightforward one-liner answers. Although these questions and issues must take centre stage to determine the future of Christianity, it is also important to look in the mirror and take note of some of the major failures, achievements and ideals that brought us to this point. History's lessons, the medals and scars from battles fought and the ideals that keep hope alive must also be included in the deliberations on which road and turns to take next.

3.1 Some failures to learn from

The most important blunder of the traditional Afrikaans-speaking churches was their willingness to act as the slave of political and ideological aspirations11 that killed their voices and effectively paralysed them. Although non-White churches and denominations spoke up against the apartheid regime, it seems that these voices also faded post-1994 and there is no strong Christian voice left to address the current corrupt state of governance in the country. Walking hand in hand with this voicelessness, Christian life is mirroring society in all that is bad, namely violence, corruption, hopelessness, hate, and despair (Oliver 2019c:5). South African Christianity also failed to promote and develop a contextual missiology, which left Christendom divided and fragmented (Oliver 2019c:5). Failing to eradicate schismatism and churchism prevented unity and cooperation (Oliver 2019d). All of these major failures contribute to the intensity of the identity crisis experienced by the traditional churches and denominations (Steyn 2005:551; 2006:674). Christians are called to be totally different from the world, but the "anything goes" mindset (Kim 2020) is pulling the institution into a spiral of death (Oliver 2019b).

Academics and students are familiar with Kübler-Ross' (1969) On death and dying and, in my opinion, South African Christians are finding themselves either caught in one of these five stages or moving between some of the stages as a direct result of the failing church. The institutionalised, formal, mostly Afrikaans-speaking churches in South Africa are mainly caught in the denial stage, while groups of Christians already moved to anger, bargaining, depression, and an acceptance that the church, or even their faith, is no longer impacting on their lives.

The strong denial to which some church leaders are clinging,12 the inward focus of the church, and the words often heard from theologians (academics and clergy alike) that everything must simply remain stable until they can retire, are adding fuel to the fire that is burning the institution and Christian life to ashes. There is no day-after-tomorrow thinking or planning. Hinssen's (2018:n.p.) principle of "move and change while you are doing well or it is too late" clearly did not figure in the churches and faculties in the second half of the previous century.13 True, the problem so clearly put forward by Hinssen about the time-consuming task of sorting out the inherited problems of yesterday that the institutional churches in South Africa brought over themselves, as indicated earlier, also prevents them from focusing on the day-after-tomorrow needs.

The CEO of Amazon, in a similar way as Kübler-Ross, describes "day 2" in business terms: Stasis, irrelevance, decline, and death (Bezos 2017). The questions are therefore: Is it too late? Did the church wait too long? Can the institution still recover from its failures? Why can we not see some revival? The current situation of the world of revolutions and the COVID-19 pandemic provide a perfect opportunity to leave the failed narrative behind and to start developing a different and new approach to being church. It is still not clear how this should be done.

It is obvious though that (South African) Christianity needs positive change agents who can create awareness about alternative ways to solve problems and have the courage to take a leap in faith towards a new "ministry of mercy" (Pillay 2017:2). The workplace for Christians in the current revolution-driven, virus-infected environment can no longer be cathedrals, lecture halls, or stadium-like churches. As Jesus and the first Christians did, believers should return to where the need (both physical and spiritual) is (for example, streets and malls). Here the "unusual suspects" of the chaos imperative (which I believe must be the core of the next theological reformation) will be noted in the manifestation of the priesthood of all believers. This means that, as in the first Christian communities, all Christians, each with his/her own talents and passions, will lead the way in faith and prayer and act upon the needs of the local communities, while also providing spiritual care and proclaiming the gospel in words and deeds.

3.2 A few achievements to build upon

Although prophets of doom claimed that secularisation would bring an end to religion,14 and many churches (mostly in Europe and the USA) closed, Christianity (and other religions) continue to grow and (new) theologies are still evolving. The Bible is still the number one best-selling book of all times (All top Everything 2021). In Africa, 49 per cent of the population were Christians in 2020 and this number is still growing. The survival and adaptability of Christianity is its most important achievement. In South Africa, with its history of abuse of Christianity, the growth and sustainability border on a miracle. The ubuntu theology of Archbishop Tutu is currently thriving, while Black liberation theology is still dominant, and gender-related theologies are gaining ground.

Secondly, theology played a major role in the establishment of universities (Boeree 2000; Haskins 1957), where it formed one of the four basic faculties together with Arts, Law, and Medicine. Despite a push to expel religion from the academic environment (also in South Africa - see Buitendag 2014; Mouton 2008:432), the theological impact on education, epistemology, and philosophy (Harrison 2009) is influencing society in general and cannot be denied. Oyler (2012:1) states that the curriculum of a higher education institution should be the place where students encounter the world, while they are encouraged to become responsible and active citizens with sound moral visions (see Oyler 2012:70). Higher education must empower people to reflect critically on their place in society (UNESCO 1997:24). However, the luxury of silo thinking as well as research and academic activities in ivory towers can no longer be the normal way of working for theologians. It will cost hard work, dedication and major adjustments to ensure that theology keeps occupying the academic space it founded and using it effectively to promote positive change and transformation in society.

The third achievement of Christianity concerns the communication revolutions mentioned earlier. From the earliest times, religions and, in particular, Judaism and Christianity implemented all available communication media to convey the message of salvation. From rituals and other actions, through the oral tradition and finally the writing of scriptures, the narrative was preserved, expanded and handed over to the ensuing generations. The Protestant Reformers used the cutting-edge technology of their time - the printing press - to get the message and their ideas into the world. From this example, the current focus should be on the optimal use of technology-based, networking tools, and all social, electronic, and digital media, in order to advance and coordinate the proclamation of the gospel.

The fourth major achievement of Christianity is the invention of numerous charity organisations, healthcare systems, several inventions, and even its stimulus for scientific research (Hill 2005; Schmidt 2004; Sunshine 2009). A detail of these successes is beyond the scope of this article. The Christian church in South Africa is the strongest non-governmental organisation (Erasmus 2005). The women associations of Christian denominations, in particular, significantly contribute to the establishment of charity organisations, shelters, orphanages, retirement homes, and funding for higher education. A few years ago, government admitted to its inability to promote positive social transformation and asked religious institutions, with their widespread networks, to provide such infrastructure by using governmental funds (Jackson 2007).

It is clear that Christianity in South Africa succeeded in achieving memorable milestones upon which to expand and build.

3.3 Ideals for the way forward

This brings me to the ideals that, I think, Christianity should make a reality in the next few years. Every individual would have his/her own thoughts on this and because of the nature of ideals, which could amount to volumes of documents, I will restrict my comments to one paragraph and then move on to how I think theological education must be done, in order to keep theology as a relevant and sought after academic discipline in the 21st-century world.

There is no option available to turn back to our comfort zone and traditional ways of practising faith, theology, and institutionalised religion. First, the prophetic voices of Christians that are altering the world through ideas and deeds must be heard, experienced, and proclaimed. Through leaps of faith and guided by prayer and the word of God, Christians must once again, like Jesus and his followers of the first centuries, focus on what is important and bring positive change and transformation to a broken world. This could imply the death of the church as institution, as we currently know it (Oliver 2019c). Theological theories must be flexible enough to adapt to and provide for contemporary challenges (Van den Toren 2016:62). This will also imply a return to unconditional, childlike faith (keep the dogma to the academic sphere); acceptance of the authority of Scripture (and agree to disagree on the interpretation thereof - see Oliver & Oliver 2020), and practically live the commandment to love God and others in all circumstances (without any add-ons, or "yes but" arguments).

Lastly, people living in the 21st century are experiencing the move towards multiple citizenships, as was the case during the first years of Christianity on earth (Tickle 2012:133). As in the 1st century, identifying with the Christian faith must, therefore, convey visible and sustainable positive change, especially in South Africa, where long-term positive transformation of actions, behaviour, and value systems are needed. On the one hand, Christianity brought radical and important changes to the world. On the other, late President Nelson Mandela (n.d.) once said that education is a powerful weapon that can be used to change the world. Theology and higher education combined can and should be the tool that brings positive change to society. Therefore, a few final words must be said about theological training.

4. TEACHING THEOLOGY

Warwick (2017:n.p.) argued that, "[i]n this new era of artificial intelligence, students still need intelligent assistance". This is one of the baselines upon which effective education must be structured. Sadly, current higher educational adjustments do not match the speed with which the revolutions are changing the world. Some of the methods and models of teaching, learning, and assessment such as lecturing that were introduced when universities first developed, are often still used as the only tuition strategy. At the beginning of this century, Passmore (2000) lamented that it took overhead projectors 40 years to move from bowling alleys to classrooms. The quote by Bates (2010:22) of a vice chancellor who said that universities are like graveyards - when you want to move them, you do not get much help from the people inside - emphasises that the problem is not so much technology itself, but rather people who fail to use technology effectively in educational environments. It must be stressed though that technology does not replace teaching or learning. Technology can only assist as a tool in the learning process. Just as the products of the printing press assisted education for a very long time, technology can provide support to effective education strategies. In addition, educational change cannot happen successfully through a single technological paradigm shift. It should be achieved through the adaptation of, and commitment to a process of continual change and development at all levels of education and with the help and support of constantly adding new tools and experimenting with new developments (Ice 2010:158). Once again, the example of how Christianity used the products of the communication revolutions to spread the gospel can serve as inspiration to implement the current explosion of media, in order to teach, reach out, and bring positive change.

Another equally important footing upon which effective education rests is an ethical and morally sound foundation. Educational design is built upon ideology. During the 19th century, the ideology behind educational systems was mainly capitalism and imperialism, while more recently education became enslaved by economic systems (Roche 2017:623). Social equality, moral and ethical behaviour, and responsible citizenship cannot be attained in the secular educational programmes, as these were never included in the design or projected outcomes of education. The current level of education, with its focus on politics, economy, and science, excludes lifelong, self-determined, sustainable, morally sound learning that values people for who they are, as summarised in the words of Dr Bostrom (Coughlan 2013): "We're at the level of infants in moral responsibility, but with the technological capability of adults". On this statement, Kapoor (2014:207) elaborates by labelling society as "extractive". People extract the maximum from the earth in terms of crops, fuels, minerals, metals, and so on, while society extracts everything possible from people:

So we ... have been extracting whatever we can from whomever we can - ironically, the result is - the more we extract, the more depleted we feel (Kapoor 2014:207).

Miller (2008:4) acknowledges the hybrid and multifaceted character of society, where religion and faith dominate parts of life and culture. In South Africa, there is a need for theological training and academic reflection on theological issues, as over 80 per cent of the South African population claims to be Christian (Statistics South Africa 2004:28). The need for graduates who can voice Christian responses to public issues and act as positive agents of change is growing as the social, economic, and political environments in South Africa are deteriorating. Through functioning in the epicentre of society (Tracy 2002), the importance of theology as an active voice in the public sphere (Mouton 2008) to promote change, renewal, and transformation is clear.15 Theological education can and should set the example of how higher education can effectively incorporate 21st-century knowledge, skills, capabilities, and competencies with morally and ethically sound principles to develop responsible citizenship and a "learning society" (Roche 2017:624) fuelled by self-directed, lifelong education.

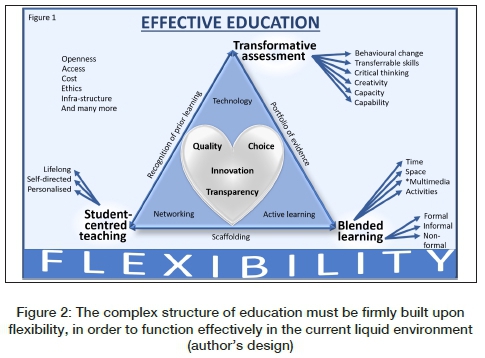

This could be achieved by implementing the triangle of effective education to ensure that the theological curriculum actively promotes graduateness and change agency. As this is discussed elsewhere (Oliver 2019c), I will only provide a short summary in this instance.

Effective education takes place when teaching, learning, and assessment are in line with each other (Huerta-Macias 1995:8) and built upon the fourth revolutions world foundation of flexibility. Effective education must be student-centred, assessment-centred, competency-centred, and community directed (Watkins et al. 2002). It does not only transfer knowledge and skills, but also enhances behavioural change (Mayer-Mihalski & DeLuca 2009) and instils values. Faith integration is the process of combining the Christian faith and religious experience with the rest of one's life experiences (Cafferky 2012), while theological education is structured in such a way that the student is motivated to not only gain knowledge and skills, but also instigate positive change in the community through the transfer of gained knowledge, skills and competencies. Therefore, when designing a theological module or course, academics must identify and construct a list of the most important things that students should learn and accomplish. These top priorities of what students must know, believe, understand, implement, and on what they should change their minds and behaviour and views - the outcomes of transformative education - must form the starting point for the design to equip Christians as change agents and responsible citizens.

5. CONCLUSION

One of the dangers of experiencing a pandemic is that we become so focused on this invasion of our lives that other equally important changes and developments can go unnoticed and cause nasty surprises for which we did not prepare. The new-normal COVID-19 society, together with the changes brought about by the fourth revolutions world is widening the existing gap between the praxis of faith and theological theory. Therefore, if theology wants to continue its front-end interaction with society as it did through history, theologians must leave the sanctuary of the ivory tower to engage and interact with both the developments and opportunities that the fourth revolutions world offers and also once again become active at street level.

Similar to the 1st century, when faith was a way of living that influenced and directed all parts of life, Christianity must revolve or rotate back to its starting point and, in line with the current trend of the industrial revolution, blur the lines and dismantle the carefully constructed walls that separate faith from the rest of our existence. Faith must infuse all aspects of life. Human self-awareness developments ensure that theology can seek, explore, and better understand our relationship with God, each other, and our environment.

Similar to the way in which Christianity took advantage of the technological advancements made during the communication revolutions, the current expansion of communication media must be implemented to share the gospel and to reach out to all people.

Unfortunately, none of this will happen easily as theology has slumbered in comfort zones for too long. Although Christ himself ensures that his church prevails, reality shows that human error and failures have brought some of the mainline churches in South Africa into a spiral of death, while a large group of Christians are seeking alternatives to the institutionalised church. The institutionalised churches must be awakened by disruptive and challenging confrontations with reality. By asking uncomfortable and nagging questions and bringing upsetting issues to the attention of society and Christians, in general, should spark interest and innovation. Theological education will have no choice but to engage with and present morally and ethically sound teaching and practices that should then flow to students, graduates, and society through positive actions and stimulants.

In a nutshell, theologians, especially within the South African context, must honestly admit to the mistakes made and the damage done, while correcting and rescuing what can be salvaged. Thereafter, a new path must be carved out through prayer and hard work as followers of Jesus. Christians must build on the accomplishments of the past and create flexible and adaptable spaces for theological innovation and creation that can turn Christian ideals into sustainable realities in the evolving world.

In the current, chaotic situation, identifying with the Christian faith through a living relationship with God, each other, and our environment must once again convey visible and sustainable positive change. "We have it in our power to begin the world over again." (Paine 1776:161). Let us then start.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

All top Everything. 2021. Top 10 best-selling books of all times. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.alltopeverything.com/top-10-best-selling-books-of-all-time/ [4 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Bates, T. 2010. New challenges for universities: Why they must change. In: U.-D. Ehlers & D. Schneckenberg (eds), Changing cultures in higher education: Moving ahead to future learning (Heidelberg: Springer), pp. 15-25. [ Links ]

Bezos, J. 2017. Jeff, what does day 2 look like? The Digital Matrix. 14 April 2017. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://thedigitalmatrixbook.com/insights/2017/4/14/jeff-what-does-day-2-look-like [21 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Boeree, O.G. 2000. The Middle Ages. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/middleages.html [13 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Brafman, O. & Pollack, J. 2013. The chaos imperative: How chance and disruption increase innovation, effectiveness, and success. London: Piatkus. [ Links ]

Buitendag, J. 2014. Between the Scylla and the Charybdis: Theological education in the 21st century in Africa. HTS Theological Studies/Teologiese Studies 70(1), art #2855, 5 pages. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i1.2855 [ Links ]

Oafferky, M.E. 2012. Management: A faith-based perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [ Links ]

Ooughlan, S. 2013. How are humans going to become extinct? BBC News. 24 April 2013. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-22002530 [24 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Daniels, R.V. 2006. The fourth revolution: Transformations in American society from the sixties to the present. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Erasmus, J. 2005. Who are the people with no religion? In: J. Symington (ed.), South African Christian handbook 2005/2006 (Cape Town: Lux Verbi), pp. 87-101. [ Links ]

Floridi, I. 2014. The 4threvolution: How the infosphere is reshaping human reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Gous, I.G.P. 2021. Rethinking the past to manage the future: Participating in complex contexts informed by biblical perspectives. HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 77(3), a6316. 13 pages. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i3.6316. [ Links ]

Harrison, P. 2009. The fall of man and the foundations of science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Haskins, C.H. 1957. The rise of universities. New York: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Hill, J. 2005. What has Christianity ever done for us? How it shaped the modern world. Downers Grove, ILL: InterVarsity Press. [ Links ]

Hinssen, P. 2017. The day after tomorrow: How to survive in times of radical innovation. Amsterdam: Terra Lannoo Publishers. [ Links ]

Hinssen, P. 2018. The day after tomorrow. Keynote address. Digittec2018. [Online.] Retrieved from: Europa.eu/digitec/2018/events/keynote/ [1 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Huerta-Macias, A. 1995. Alternative assessment: Responses to commonly asked questions. TESOL Journal 5(1):8-10. [ Links ]

Ice, P. 2010. The future of learning technologies. Transformational developments. In: M.F. Cleveland-Innes & D.R. Garrison (eds), An introduction to distance education: Understanding teaching and learning in a new era (New York: Routledge), pp. 155-164. [ Links ]

Jackson, N. 2007. Staat gee geld vir armes in pakt met godsdiensgroepe. Beeld, 25 Julie 2007, p. 4. [ Links ]

Joubert, S. 2018. "Flowing" under the radar in a multifaceted liquid reality: The e-kerk narrative. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 74(3), 4966. 7 pages. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i3.4966 [ Links ]

Kallaway, P. 2012. History in senior secondary school CAPS 2012 and beyond: A comment. Yesterday and Today 7:23-62. [ Links ]

Kapoor, M. 2014. Redefining progress and ushering in the fourth revolution. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 133:203-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.185 [ Links ]

Kgatle, M.S. 2018. The prophetic voice of the South African Council of Churches: A weak voice in post-1994 South Africa. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 74(1), a5153. 8 pages. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i1.5153 [ Links ]

Kim, I. 2020. Most people believe salvation is earned by being good. Christianity Daily. 20 August 2020. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.christianitydaily.com/articles/9691/20200820/most-people-believe-salvation-is-earned-by-being-good.htm [20 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Kübler-Ross, E. 1969. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Kulik, J.A. 1984. The fourth revolution in teaching: Meta-analysis. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Paper presented at 68th New Orleans Conference, Los Angeles, 23-27 April 1984. [ Links ]

Levy, J. 2005. The fourth revolution: What's behind the move from brute force to a brain force economy? TD June 2005:64-65. [ Links ]

Lorber, J. 2018. The social construction of gender. In: D.B. Grisky & S. Szelényi (eds), The inequality reader: Contemporary and foundational readings in race, class and gender (New York: Routledge), pp. 318-325. [ Links ]

Mayer-Mihalski, N. & DeLuca, M.J. 2009. Effective education leading to behavior change. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.paragonrx.com/experience/white-papers/effective-education-leading-to-behavior-change/ [24 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Mdaka, Y. 2020. Covid-19: Here's how risky normal daily activities are according to doctors. News24: W24. 23 July 2020. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.w24.co.za/SelfCare/Wellness/Body/covid-19-heres-how-risky-normal-daily-activities-are-according-to-doctors-20200715 [25 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Miller, J. 2008. What secular age? International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 21(1):5-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-008-9037-5 [ Links ]

Mouton, E. 2008. Christian theology at the university: On the threshold or in the margin? HTS Hervormde Teologiese Studies 64(1):431-445. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/htsv64i1.21 [ Links ]

Norris, P. & Inglehart, R. 2011. Sacred and secular: Religion and politics worldwide. Second edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Oliver, E. 2019a. The great emergence: An exposition. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 75(4), a5398. 12 pages. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5398 [ Links ]

Oliver, E. 2019b. The church in dire straits. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 75(4) Special collection: The Church in need of change (agency). 7 pages. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5577 [ Links ]

Oliver, E. 2019c. The triangle of effective education - implemented for Theology. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 75(1). Special Collection: OEH: The Online Educated Human, sub-edited by Ignatius Gouws (UNISA). a5234. 8 pages. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v [ Links ]

Oliver, E. 2019d. Religious Afrikaners, irreligious in conflicts. HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 75(1), a5204. 7 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102hts.v75i1.5204. [ Links ]

Oliver, W.H. & Oliver, E. 2020. Sola Scriptura: Authority versus interpretation? Acta Theologica 40 (1):102-123. https://doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v40i1.7 [ Links ]

Online Etymology Dictionary 2018. "Revolution". [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.etymonline.com/ (25 April 2020). [ Links ]

Oyler, C. 2012. Actions speak louder than words: Community activism as curriculum. New York:Routledge. [ Links ]

Paine, T. 1776. Common sense. Philadelphia: W&T Bradford. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/147/147-h/147-h.htm [24 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Passmore, D.I. 2000. Impediments to adoption of Web-based course delivery. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://train.ed.psu.edu/documents/edtech/edt.pdf [25 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Pillay, J. 2017. The church as a transformation and change agent. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 73(3). 4352. 12 pages. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4352 [ Links ]

Prins, J. 2018. Kom ooreen om te verskil. Beeld, 3 November 2018. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.pressreader.com/southafrica/beeld/20181103/281487867355287 [4 January 2020]. [ Links ]

Richardson, N. 2005. The future of South African theology: Scanning the road ahead. Scriptura 89:550-562. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7833/89-0-1037 [ Links ]

Roche, S. 2017. Learning for life, for work, and for its own sake: The value (and values) of lifelong learning. International Review of Education 63:623-629. doi: 10.1007/s11159-017-9666-x [ Links ]

Schmidt, A.J. 2004. How Christianity changed the world. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Schwab, K. 2016. The fourth Industrial revolution: What it means, how to respond. World economic forum. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/ [2 January 2020]. [ Links ]

Shenk, W.R. 2011. Enlarging the story: Perspectives on writing world Christian history. . Eugene, Oregon USA:Wipf and Stock publishers. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa 2004. Primary tables. Pretoria: Stats SA. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa 2018. Mid-year population estimates. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022018.pdf [5 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Steyn, G.J. 2005. Die NG kerk se identiteitskrisis. Deel 1. Aanloop, terreine van beïnvloeding en reaksies. Nederduitse Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif 46(1 & 2):550-559. [ Links ]

Steyn, G.J. 2006. Die NG kerk se identiteitskrisis. Deel 2. Huidige bewegings, tendense of mutasies. Nederduitse Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif 47(3 & 4):661-676. [ Links ]

Sunshine, G.S. 2009. Why you think the way you do: The story of western worldviews from Rome to home. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Tickle, P.N. 2008. The great emergence - How Christianity is changing and why. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. [ Links ]

Tickle, P.N. 2012. Emergence Christianity: What it is, where it is going and why it matters. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. [ Links ]

Tracy, D. 2002. On theological education: A reflection. In: R.L. Petersen & N.M. Rourke (eds), Theological literacy for the twenty-first century (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans), pp. 13-22. [ Links ]

UNESCO 1997. "Declaration of Thessaloniki", in International Conference on Environment and Society: Education and Public Awareness for Sustainability, UNESCO and the Government of Greece, viewed 06 March 2016, from http://www.unesco.org/iau/sd/rtf/sd_dthessaloniki.rt [ Links ]

Van den Toren, B. 2016. Distinguishing doctrine and theological theory - A tool for exploring the interface between science and faith. Science and Christian Belief 28(2):55-73. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, D.G. 2019. Rethinking the message of the church in the 21st century: An amalgamation between science and religion. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 75(4), a5472. 9 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5472 [ Links ]

Vanhoutte, K.K.P. 2020. The revenge of the words: On language's historical and autonomous being and its effects on "secularisation". HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 76(2), a6076. 9 pages. doi: https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v76i2.6076 [ Links ]

Warschauer, M. & Matuohniak, T. 2010. New technology and digital worlds: Analyzing evidence of equity in access, use, and outcomes. Review of Research in Education 34(1):179-225. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X09349791 [ Links ]

Warwick, P. 2017. Intelligent as well as artificial assistance needed. University World News, 15 December 2017. [Online.] Retrieved from: Universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20171212144321444 [8 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Watkins, O., Carnell, E., Lodge, O., Wagner, P. & Whalley, O. 2002. Effective learning. National school improvement network research matters. Vol 17:1-8 [ Links ]

Date received: 25 September 2020

Date accepted: 19 March 2021

Date published: 14 June 2021

1 We need to bear this in mind, as in the case of the historic revolutionary and disruptive events.

2 Three additional fourth revolutions - some of them overlapping with those mentioned earlier - are noteworthy (and these are probably not the only ones). Daniels (2006:ix, x) states that the first revolution was the German and Dutch and later the English religious reformations. The second revolution came about by the French social revolution, followed by the economic revolution that started with the Russian revolution and which is still incomplete. The fourth revolution is social protest that seeks ultimate personal freedom and equality that started in 1960 and includes, among others, racial freedom (Daniels 2006:73), youth (Daniels 2006:97) and gender equality (Daniels 2006:119). Levy (2005:64) refers to the first three revolutions as agricultural, industrial, and information revolutions, and adds the fourth, developing revolution as the expansion of the full potential of knowledge workers to deal with information and mental techniques. Kulik (1984:23) refers to the four revolutions that influenced education, namely writing, printing, the move of children from homes to schools (institutions), and electronic technologies.

3 Gous (2021:3) rightfully points out that popular tagging of events and developments can often lead to a "skewed perspective of reality". He questions whether the fourth as well as the previous three industrial revolutions are rightly described as revolutions, or whether they evolved over time, a question that can also be applied to most of the other types of revolution.

4 It is likely that this will label Floridi as the father of the Fifth Revolution in Self-Understanding.

5 For a more detailed discussion on the development of the meaning of the term "revolution" and the tendency of words to retain their original meaning in spite of later changes to the meaning, see Vanhoutte (2020).

6 Religious gatherings are identified as a main spreader of the COVID-19 disease in South Africa (Mdaka 2020). According to doctors, the attendance of religious services with 500 or more people is rated at 8 on a scale of 1 to 10, and attending funerals or weddings with 50 people maximum, on 7 out of 10.

7 Although this may seem a tall order, Jesus focused his actions and messages on the needs and actions of individual people (such as the sick) and groups (such as the Pharisees).

8 The pattern for dealing with chaotic and disruptive change includes the creation of a white space, the recognition and utilising of unusual suspects, and the implementation and expansion on the findings and opportunities gained from organised serendipity or blind discovery.

9 The trend to manage a church or congregation as if it is a business often leads to implementing prosperity gospel theology which, if compared to the gospel that Jesus proclaimed, is, in my opinion, a false theology. The woman who brought a few cents to the temple (Luke 21:2) did not receive a life-changing gift in return.

10 A white space provides a time to think and helps people gain perspective, while looking for patterns and starting to pave a way forward.

11 The Afrikaans-speaking churches in South Africa lost their mobility and change agency even before settling on this continent, as religion was a handmaid of the colonial governments (both the Dutch and the British, and later also the Afrikaner National Party), as well as trapped in the confinements of culture (the need of the church for confirmations, marriages, and funerals) and tradition (status symbol). The world outside the church changed drastically and these old strings became garrottes.

12 Dr Bartlett, moderator of the Highveld synod, recently state that the NG Church is "so bietjie besig om agteruit te boer" - going backwards a little bit (Prins 2018:16).

13 Stats SA indicates that, in 1985, over 5 per cent of the population of South Africa was members of the three traditional Afrikaans-speaking denominations. By 2018, this number had dropped to roughly half a per cent of the population (Stats SA 2018).

14 Auguste Comte, Herbert Spencer, Émile Durkheim, Max Weber, Karl Marx, and Sigmund Freud strongly expressed their views that religion will soon become less important (Norris & Inglehart 2011:3).

15 For example, theology played a major role in both establishing and demolishing apartheid, but it sadly fell into silence post-1994. For a summary of comments on the prophetic voice becoming weak and silent post-1994, see Kgatle (2018).