Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.40 suppl.30 Bloemfontein 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.Sup30.8

ARTICLES

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.Sup30.8

Spirituality as passions of the heart. An empirical study into the character, core values and effects of the passions of the heart of general practitioners

Prof. C.A.M. HermansI; Mr. L. KornetII

IExtraordinary Professor, Department Practical and Missional Theology, University of the Free State, and Professor of Practical Theology, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. (orcid.org/0000-C001-9416-3924) c.hermans@ftr.ru.nl

IIResearch student, Department of Philosophy, Theology and Religious Study, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, and spiritual counsellor at a home for retired people in Ede, The Netherlands. (orcid.org/0000-0002-5919-4423) c.hermans@ftr.ru.nl

ABSTRACT

There is growing interest in the spirituality of physicians, relating to burnout and emotional stress and in terms of dealing with their workload. The authors distinguish four different lines of research in this area and position their approach of the "passions of the heart" as a meta-intentional feeling for what is good and satisfying, which we derive from a phenomenological theory of feeling by Stephan Strasser (1977). Human beings are characterised by a transcendental openness that interpenetrates human feelings. Four markers of passions of the heart are identified: fulfilment, receptivity, life-organising power, and ethical nature. Based on these markers, the article distinguishes between concerns identified as passions of the heart, and other concerns. Four core values are identified in the concerns of general practitioners (GPs) studied: personal proximity, self-direction, the whole person, and giving all people access to the healthcare they need - specifically the vulnerable. Finally, the authors present the GPs' testimonies, in which they voice that passions of the heart mitigate the effects of negative experiences (emotional stress and burnout) and inspire and motivate them in their work.

Keywords: : Passions of the heart; Fulfilment; Receptivity; Life-organising power; Ethical nature

Trefwoorde: Passie van die hart; Vervulling; Ontvanklikheid; Lewens-organiserende krag; Etiese natuur

1. INTRODUCTION

There is a massive amount of research showing that physicians suffer from emotional stress and burnout, which has a huge effect on their quality of life as well as on the quality of care that they are able to give (Wiederhold et al. 2018; Karr 2019). There are multiple reasons why physicians suffer from emotional stress and burnout. One reason is their continual confrontation with emotional situations such as death and suffering that deal with the brokenness and contingency of human life. Another reason is that they experience conflict between giving the care they want to give and aspects such as bureaucracy, market forces, and a focus on productivity (Van Luijn & Maalsté 2016:253). These cause physicians to lose intrinsic motivation (Movir 2012).

At the same time, the physicians' workload is increasing, due to changes in patterns of illness, and the fact that, in most parts of the world, people now live to a greater age than they did previously.

The number of people living with chronic diseases for decades is increasing worldwide; even in the slums of India the mortality pattern is increasingly burdened by chronic diseases (Huber 2011:236).

Health is no longer defined as the absence of disease, but as the ability to adapt and self-manage well-being in three domains: physical, mental and social. In addition, there is growing awareness of what might be called a humanist perspective on the professionality of GPs (Des Ordons et al. 2018), and a movement towards so-called positive healthcare (Huber & Jung 2015). It all adds to the growing pressure on the workload of physicians. It promotes the feeling that work never stops; yet, at the same time, physicians feel that they must do more in all domains of health.

Against this background, we observe the growing interest in the topic of spirituality related to the problems facing physicians in their work (as indicated above). On the one hand, it is suggested that spirituality can help in dealing with emotional stress and burnout and, on the other, it can strengthen intrinsic motivation, and offer important core values of the profession. In this study we want to contribute to the theory-building and measurement of spirituality in relation to the professionality of physicians. In section 2, we introduce different lines of research in this area, and distinguish four different definitions of spirituality in this debate. In section 3, we introduce a new definition of spirituality, which can overcome the shortcomings of the four approaches presented in section 2. We define spirituality as a passion of the heart, as a meta-intentional feeling towards what is good and satisfying, which we derive from a theory by Strasser (1977). In section 4, we introduce the research design and describe the results of our research into GPs' passions of the heart. We conclude this article with a summary and discussion in section 5.

2. SPIRITUALITY AND WELL-BEING OF PROFESSIONALS

What do we know about the effects of spirituality on the well-being of physicians? In this section, we briefly present the state of the art in the study and theory of this field of research. We map four different approaches in the field of research on spirituality and the well-being of professionals.

A first approach defines spirituality as a kind of emotional-energy "account" that can be filled by the breathing techniques of mindfulness meditation. Spirituality has to do with emotions (feeling), and people can practise certain techniques to boost this energy. According to Karr (2018:93), the current evidence illustrates that there are three factors effective in decreasing stress and promoting high-quality sleep among physicians: physical exercise, healthy diet, and spirituality. Under the heading of spirituality, Karr includes practising religion, yoga, meditation, mindfulness, and Tai Chi.

Practising mindfulness is about being fully aware of what is happening in the present moment, acknowledging one's thoughts, feelings, and body sensations with compassion and devoid of all judgment (Karr 2018:94).

In a similar vein, another review study reports a set of techniques such as training in coping strategies, training in interpersonal skills to increase social support, and the use of relaxation techniques for diminishing stress (Wiederhold et al. 2018).

A second approach provides a more substantial definition of spirituality. Wachholtz and Rogoff (2013) report that students, who had higher levels of spiritual well-being and daily spiritual experiences, described themselves as more satisfied with their life in general, while students with low scores on spiritual well-being and daily spiritual experiences had higher levels of psychological distress and burnout. Spirituality is measured by the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES) (Underwood 2011). This scale measures how we perceive the transcendent in our daily lives - in phrases such as "I feel thankful for my blessings". It conceptualises spirituality and religion as overlapping domains. This means that the scale is biased towards religious people.1

In a third approach, the concept of spirituality refers to processes of inner transformation related to problems in relation to the self, others, and God. An example is Swart (2015a; 2015b), who derives three movements of transformation from Henri Nouwen.

• The first transformation, from loneliness to solitude, focuses on the spiritual life as it relates to our own experience. For example, physicians experience the emotion of restless loneliness when a patient dies or experiences complications.

• The second transformation, from hostility to hospitality, deals with our spiritual life as a life for others. In this instance, Swart refers to the impotence a physician may experience when dealing with the limits of medical treatment, frustrations with patients' lifestyle choices, and confrontation with patients, relatives, or referring physicians.

• The third transformation, from illusion to prayer, offers penetrating thoughts on the most mysterious relationship of all: our relationship with God. It is a movement towards seeking God's presence in the outcomes after cardiac surgery.

Swart also makes a strong connection between spirituality and dealing with emotions, similar to the first type of research. Just like the second type, Swart has a bias towards religious persons in defining spirituality as the second type.

Finally, we must mention a fourth type that uses ideals (Van Luijn & Maalsté 2016), or life goals (Schippers 2017) as an overarching concept, and that subsumes spirituality into this concept. This type is typical for much of the research into workplace spirituality in public institutions and businesses. Life goals provide a sense of meaning and purpose to life and give centrality to our identity (Schippers 2017:20). The role of life goals is to regulate our behaviour in terms of both goal-setting and goal-achievement plans (job motivation) and dealing with contrast experiences (stress, absence of values). Although Schippers (2017:9) writes that finding a purpose in life often requires a lengthy search, she also presents a goalsetting intervention programme aimed at finding a purpose in life, while simultaneously ensuring that we make concrete plans to work towards the life goals we have set for ourselves. In this type, emotions are less central, compared to the first type; but both types share the idea that we can establish life goals through the right techniques and practices.

3. PASSIONS OF THE HEART

We propose a new approach to spirituality as a source of inspiration and motivation for physicians and professionals, in general. What is new in approaching spirituality as passions of the heart? First, we consider the goal of spirituality beyond human intentionality. We define passions of the heart as a meta-intentional disposition, not as a goal that can be reached through techniques or practices. Spirituality as passions of the heart refers to experiences, in which we are "being apprehended", "being overpowered"; that is above and beyond what human beings can realise (Strasser 1977:294). What individuals and communities can learn is how to practise discernment.2 Spiritual experiences that inform discernment are not manageable; neither can they be created.

Secondly, we consider passions as a felt state of mind, in which we experience our relationship with the world. We disagree with approaches that define spirituality as emotional energy. What is missing, in this instance, is an openness to the absolute. We define the "heart" as

the mutual interpenetration of spiritual and felt processes and the configurated whole of human existence that rests upon this interpenetration (Strasser 1977:199).

Human beings are characterised by a transcendental openness that interpenetrates human feelings. The human soul is the embodiment of a finite spirit, but with an appetite for the absolute (Tallon 1992:356).

Thirdly, we agree that spiritual and religious experiences are related phenomena; but they are not similar. What they have in common is "a desire for the absolute", for that which is meaningful as such (Tallon 1992:345). What Joas (2016) calls a human experience of self-transcendence and Strasser (1977) calls transcendental openness does not necessarily include belief in God. It is possible for the concept of passions of the heart to define spiritual experiences without presuming a belief in God.

Fourthly, we opine that the idea of transformation is a core concept in spirituality (see Swart 2015a; 2015b). Hermans (2019) defines the transformation of the heart as an eschatology of restored capabilities. Transformation of the heart refers to a shift from impossible to possible; for example, from not being able to forgive, to the possibility of forgiveness. Passions of the heart are a gift that transforms us on the level of purpose -for example, the possibility of forgiving (meta-intentionality). The essence of this transformation is a restoration of freedom, versatility, and world governance. The transformation of the heart (meta-intentionality) expresses itself in a restored capability of "I-can-forgive" (intentionality).

Being able to perceive possibilities that are experienced as absolute shows that man is a being gifted with spirit ("logos").3 The highest form of human becoming is defined as the soul, "the bearer of the idea of man as a being which is also spiritual" (Strasser 1977:170). On the level of the spirit, human beings are able to project completely abstract values such as peace, health, beauty, and truth. How is that possible?

World is first of all distinguished from environment in that not only the real, but also pure possibilities belong to the World. Such possibilities are not grasped by feeling but are seen by thought. The Logos indeed, among other things, the possibility of grasping, ordering and fixing abstract connections in concepts and categories, and on that basis, advancing to new insights (Strasser 1977:246).

With this subordination of goals to purpose, an entirely new situation is created. Now man makes values or goods the primary object of his willintention, which gives his freedom much room in which to play. The notion of passions of the heart refers to the interwovenness of the level of the spirit as openness to the absolute and human dispositions of deeply felt directedness to the world. For this reason, we opine that this approach to spirituality is more adapted to issues of emotional stress and burnout.

Passions are a specific kind of basic transcending awareness.4 The ideal possibility (transcendence) is felt as a reality of (or in) our lives. This overwhelming power gives us the enduring power to transform social life forms and institutions to operate in line with this absolute good.5 Passions are characterised by four markers.

1. Passions are characterised by a transcending mode: they absolutise a region of value that affords fulfilment of life. The absolute (or absolutised) good surpasses everything that man has experienced before, in fullness, perfection, and value. The affirmation of a region of value is absolute, in the sense that it is affirmed once and for all.

2. Passions are marked by receptivity, which refers to an experience of being apprehended, being overpowered, being mastered. When we are drawn to the absolute good, we can "respond" in no other way than in a mode of unreserved receptivity. In passions, the felt mode of preparedness manifests as a heightened susceptibility and capacity for being apprehended by the valuable.6

3. Passions have a life in organising and concentrating power. The behaviour of the passionate person is distinguished by consistency, perseverance, composure, and awareness of goals. A person who is passionate is able to dedicate him-/herself unreservedly to a single thing: what is meaningful and satisfying.

4. Passionate concentration has an ethical nature, and always has as its object an accustoming of ourselves to a definite region of value such as peace, care, sustainability of nature, or love. This region of value emerges in concrete bearers of value; for example, when care is manifested in caring for sick people, or for migrants. Characteristic of this passionate concentration is a drive towards what is beyond ourselves. This drive manifests itself as

an increase in power in the intensity of willing, of preparedness for sacrifice, of the gift of sensitivity for the discovery of means, and, in general, in the productivity of the heart (Strasser 1977:295).

4. RESEARCH DESIGN

In this section, we first formulate the research questions. Next, we describe the research method and instruments as well as sample and data collection. Finally, we describe the design of the analysis.

4.1 Research questions

The following research questions were formulated:

1. Which concerns of GPs can be characterised as passions of the heart?

2. What are the core themes of these passions of the heart?

3. How do the passions of the heart affect the work practice of GPs?

First, we expect that some concerns are ultimate when they express the passions of the life of the spirit (see section 3). Passions of the heart are characterised by fulfilment, receptivity, a life-organising power, and an ethical nature. Concerns that are not defined by these markers of ultimacy are final goals.

Secondly, we expected that GPs would articulate concerns related to the intrinsic values of their work, specifically humanist values (first research question).

Thirdly, if concerns are ultimate, we expect that they will be a source of job satisfaction ("this is what I do it for"; "this is why I became a general practitioner") and have the power to help the GP deal with emotional stress and work frustration ("this is not how I want to be as a GP").

4.2 Research method and instruments

This exploratory study uses the concept of passions of the heart to research the concerns of GPs. We used an existing interview instrument into personal biography, which was developed by Van den Brand et al. (2015) to research existential events on the lifeline, experiences of contingency, ultimate concerns, and the religious foundation of such concerns. For our research, we added a question on dealing with the influence of concerns as general practitioner, in positive and negative situations. We used the following definitions for the four markers of passions of the heart.

1. Fulfilment: An awareness of something absolute, in itself bringing happiness and satisfaction, which can never be saturated in the pursuit of striving towards this absolute.

2. Receptivity: The feeling of being apprehended by what is considered to be an ultimate good, either in an event such as an encounter, or by a process of gradual crystallisation during life. When we are drawn to the absolute good, we can "respond" in no other way than in the mode of unreserved receptivity.

3. Life-organising: Being able to dedicate ourselves unreservedly to what is considered in itself absolute and satisfying, in such a way that it gives orientation and structure to everything in life.

4. Ethical nature: Aiming at a region of value, a quality of life, or a good life with and for others, which cannot be manipulated instrumentally.

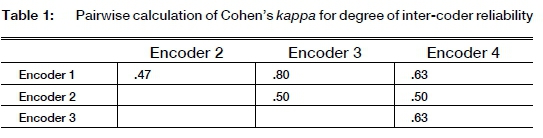

We used Cohen's kappa to calculate the degree of reliability, following the procedure of Van de Brand (2016:119). The coders were given a description of a code and an example of an interview fragment, to which the researcher had assigned this code. Next, the coders were presented with other fragments, and were asked whether or not they would assign the code just described to these fragments. Our test consisted of 12 fragments: three for each code. Four items were false examples.

Table 1 presents the pairwise result of Cohen's kappa among five coders. There are three kappas between .40 and .50 (moderate agreement), and three kappas between .60 and .80 (substantial agreement) (Landis & Koch 1977). We consider this a sufficient level of agreement between the coders.

4.3 Sample and data collection

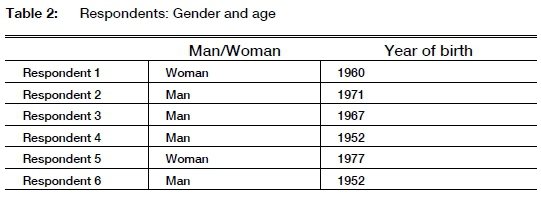

Respondents were recruited using the snowball method (Babbie 2008:205). We did not expect to get many respondents to a general call to participate in the study. Many GPs have very full schedules, and the interview takes between two and a half and three hours. We expected that GPs would be more likely to cooperate if they were approached by fellow GPs. The researcher (Linda Kornet) was able to recruit the first respondent through her network. This respondent introduced her to two other respondents, who contacted the remainder of the respondents. This resulted in a total sample of six GPs (see Table 2): two women and four men, three mid-career GPs (aged 43-53 years), and three (aged 60-68 years) at the end of their career. Our sample has no GPs at the start of their careers.

4.4 Design of data analysis

The interviews were recorded and stored securely. We transcribed in their entirety the parts of the interviews that focused on motivations, and saved them anonymously. The data were analysed in three areas: the four markers of passions of the heart, content of the concerns voiced by the GPs, and the effect on negative experiences and inspiration and motivation.

4.4.1First research question

We used deductive coding based on the four characteristics of passions of the heart. We formulated four codes based on four characteristics of passions in the theory of Strasser: absolute good, receptivity, lifeorganising, and ethical nature (see section 3).

As a criterion for deciding whether a concern could be characterised as a passion of the heart, we demanded a minimum of three (out of the four) characteristics. We consider this to be a stringent criterion; we wanted to be certain that a chosen concern could be defined as a passion of the heart.

4.4.2Second research question

We used a list of core themes or core values mentioned in the literature on person-related healthcare (see Glas 2018:161-167; Van den Muijsenbergh 2018). This person-related approach is the dominant approach used and focuses on more than simply the clinical aspects of disease. It is likely that our respondents will mention the core values of this approach as the objects (content) of their passions of the heart. But it is a list, and we are under no illusion that it is complete. We also expected respondents to use the one core values more in formulating their concerns as passions of the heart. We only analysed concerns that could definitely be characterised as passions of the heart (see first research question).

We used the following list of core values in our research:

1. Treating the whole person, and not only his/her illness or limitations;

2. Building a relationship of trust and empathy with patients;

3. Taking into account the individual characteristics, needs, and context of each patient, and a treatment tailored to the needs of that patient, rather than offering the same for everyone (personal orientation and equity);

4. Examining the meaning of illness in each patient;

5. Determining for each patient what care would be necessary and appropriate for that person; preserving self-direction;

6. Involving patients as much as possible in decision-making (person-centred care), and in plans to improve their environment (empowerment), and

7. Being available and accessible to people from all groups.

4.4.3 Third research question

We analysed what the GPs report as the core experiences in their work. On the one hand, there are positive situations, which they characterise with phrases such as "This is why I do this work!". On the other hand, there are also negative work situations, with which they struggle. All these fragments were related to the core themes of passions of the heart that resulted in the analysis of the first research question. We examined the role that the passions of the heart play in dealing with both positive and negative situations. If there were no passions involved, we skipped the situation.

5. RESULTS

5.1 First question: Passions of the heart

Which concerns can be characterised as passions of the heart? All concerns were the result of an open interview question; the four markers of passions of the heart were semi-open questions formulated on the basis of our concept of passions of the heart. We first describe one non-example; that is, a concern that has no marker for a passion of the heart. Next, we describe an example, and end with an overview of the passions of the concerns voiced by the practitioners.

We take a non-example from Respondent 5 (see Table 2: a woman, born in 1977), who was the only respondent to voice no concern that could not be identified as a passion of the heart (Table 3, Concern 8). She summarised her concern as "Giving people insight into what is the matter". For example, if we know why we have pain in our back, we can deal with it better (as she phrased it). "Dealing with it better" is interpreted as giving people the possibility of having control over their situation (R5:35).7She did not formulate an experience of happiness, fulfilment or ultimate satisfaction (Table 3: fulfilling). According to the respondent, insight helps achieve control. She did not voice receptivity (Table 3) in the sense of being apprehended by the good. When she spoke of her concern, she used terms such as "natural inclination" (R5:23) and "mechanism" (R5:24). There is passivity, but it is not related to an (absolute) good. If she would not have this concern, she would find it an impoverishment of her profession (R5:25). But impoverishment is not the same as an organising principle of her understanding of what it means to be a GP. Finally, the ethical nature is missing. Giving insight is considered to be a quality instrumental to facilitating control.

Next, we describe a concern labelled "Being near to a person" (Table 3: Concern 6 = respondent 4) which has all the markers of a passion of the heart:

I want to be a warm physician who radiates attention and compassion for his patients. And I think that's what a patient deserves. And also, that personal continuity. (R4:10)

We need to see the "whole" person, together with his/her life context.

If you are not aware of that context, you also do not understand that people may not feel good because of it. And then you are going to treat people medically, when they need something else. (R4:27).

In itself, this concern is fulfilling and gives satisfaction. This fulfilment is experienced as a feeling that it is good. "When I notice that patients respond so gratefully to it, I think: It is good that I did it that way." (R4:17)

The second marker is receptivity. The respondent had known since his training as a general practitioner that he wanted to be a physician who would be near to his patients, in a supportive manner. But it was in practice that he felt it as a vocation. "Then I really had the feeling: Those people cannot do without me. ... And that is something special, I must say." (R4:14)

This concern is also life-organising (third marker). The person would be a different physician without this concern, although he knows that it affects him emotionally.

And then you are fifty, and then someone of thirty dies and then you think: wow, that touches me deeply. ... So I notice that increasingly, it is affecting me emotionally. I can explain that, on the one hand -that you get more emotional when you get older. At the same time, I occasionally think: how much can I actually handle? What ... But that does not mean that I want to be a physician in a different way. So that's why I doubted for a moment, about . I think I can't be a physician any other way. (R4:15)

Finally, this concern has an ethical nature. The intrinsic good that is implied in this concern is the whole person, in his context, as the aim of good care. Quality of life is a subjective measure: Every person must determine for him-/herself what is valuable to him/her (R4:27). When we do not know a person and is not near to him/her, we cannot support that person or treat him/her in a supportive manner. The medical treatment comes to the fore.

We have summarised our findings in Table 3. Concerns 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 and 10 are passions of the heart. Concerns 5, 7 and 8 did not pass our criterion of having at least three markers. These concerns will be disregarded in the ensuing analysis.

5.2.1 Concern 1: Standing up for the vulnerable and less fortunate

The first core value voiced by the GPs is to "give all people equal access to health care, specifically the vulnerable". Some people get lost in the medical system or do not fit in one particular category, so they do not get the care they need. The passion of this GP is to give vulnerable people access to the healthcare they need.

There are patients who are not so capable of finding their way in the world of the hospital ... Or vulnerable people who just get lost. Addicts who also have depression or other psychological complaints and who then simply get stuck. (R1:36)

The second core value is "self-direction of the patient". It is easier for a GP to organise the necessary care for the patient. But this would take away the core value of self-direction.

I don't want to patronise them, but for a while I think: yes, you don't have the skills to see through that, and now I want to show you the way. (R1:36)

5.2.2 Concern 2: Presence as a person

The first core value voiced under this concern is "personal proximity".

As a physician, you sometimes reach a limit, where you cannot do anything medically, or there is simply nothing you can do, but people still need support. But not so much with pills, but just emotional support, that someone puts an arm around them, just holds their hand and says: I understand ... I can't do anything for you, but I understand how you feel. And that can be very valuable. . I can show that I am also human. . There's someone next to you there. You are not alone. (R1:22)

The first aspect refers to emotional proximity in the form of good listening, empathy, or a touch that makes people feel that they are not alone. The second aspect refers to the consequence of personal closeness; that is, the feeling of being understood and seen, which gives the patient relief.

The second core value is described as "focus on the whole person".

For me it has more to do with the fact that I think health care is not enough if it is only medical-technical. . Then you only approach a human being [as] if they consist of muscles, joints, and whatever. But not ... the soul, I just call it the soul. I would like to see that [being] more holistic. (R1:29)

There are more aspects to medical treatment than simply the clinical. The GP uses the term "soul" to express this "more-than-clinical" dimension. Another term she uses is "more holistic".

5.2.3 Concern 3: Being close to a person

There are two core values voiced in this concern. The first is "personal proximity". The first aspect that this GP puts forward is to want to stand next to the patient - not above, as a medical authority. The second aspect is personal attention and interest in the life of the patient.

At least, a GP who is next to the people and not above the people. I think that has always been one of the characteristics in my consultations. ... I find personal attention and interest in someone's life very important. (R7:9)

The second core value is "self-direction of the patient".

Good care is health care that empowers people, in which you explore together with the patient what the best solution is for that patient. (R7:21)

According to the GP, self-direction incorporates shared decision-making, by exploring together what would be the best solution. It includes giving back the responsibility of self-determination to the patient. In order to give this responsibility back, we must focus on the possibilities that the person still has.

5.2.4 Concern 4: Being near in a supportive manner

The first core value voiced in this concern is "personal proximity":

to offer people in difficult situations a kind of support, reassurance, a safety. That is, to be near; to be supportive in being near. (R3:24)

I think a good GP is close to patients. "Person-oriented" means promoting a quality of life from the perspective of the experience of the patient. (R3:26)

This GP states that proximity is realised through a kind of support, reassurance, and safety.

The second aspect is to take the perspective of the patient into account in promoting quality of life. Emotions are an important element of experiences.

The second core value is "focus on the whole person". This points to matters beyond the cure of the disease, beyond the practical. Conversation seems to be both the means and the end to this focus on the whole person.

And what I enjoy the most, that's just conversation. Because I think that matters a lot more than all kinds of other things, practical things. I think I have more to offer there than giving a pill. (R3:17-18)

5.2.5 Concern 6: Being near to a person

The core value expressed in this concern is "personal proximity". This value is characterised by attention and compassion, which for this GP is expressed dominantly by an arm around the shoulder. Personal proximity also means continuity: Being there when one is needed. Finally, proximity also implies knowing the whole story of the person and his/her context.

That personal continuity ensures that you as a general practitioner are always a kind of acquaintance for that patient. ... Because he no longer has to tell the whole story - because you already know it. (R4:14)

5.2.6 Concern 9: Giving care in alignment with the person

The first core value in this concern is "the whole person". This GP compares the practice of a physician with art: One does need technical skills, but also connectedness, intuition, and a feeling for the intangible things. He seems to suggest that a diagnosis often starts with a feeling of ambiguity ("not fluff").

However, it is not possible to put a person in categories. So you have to connect the protocol to that person. And that is exactly the art. And the art consists of the technical skills. But the art also consists of connecting. And also intuition and feeling ... the intangible things. What I said: a feeling of "not fluff", of "this is correct, and that is not correct". (R6:11)

Another core value voiced in this concern is "personal proximity". To be near to people means that one knows the patient, the family, and the context. This knowledge marked by humanity creates a low threshold for the patient to speak out.

5.2.7 Concern 10: Solidarity

This GP uses the word "solidarity" to voice the core value of "giving all people access to the healthcare they need".

We have to distribute it neatly. So, a kind of solidarity. So it cannot be that one citizen, because they are in a lower social class, that they receive less care than a higher social class. Or because they have less money. (R6:28)

A second core value is "personal proximity". Being near to the person takes time, but it is required, in order to discover what the person needs. In the words of the GP: "making real contact".

5.2.8 Summary

Four core values were revealed by the GPs in our research. All practitioners voiced "personal proximity". Two practitioners voiced all other core values.

• Personal proximity. This value is about making real contact; that is, as a person to another person. The aspects included in this value are good listening; making the other feel that s/he is understood and seen; seeing the context of his/her experience; radiating warmth and compassion; real contact expressed in physical touch; allowing oneself to be touched emotionally, and to bring in one's own humanity.

• Self-direction of the person. This value aims at shared decision-making, by exploring together what the best solution is for the patient. It includes giving back the responsibility of making decisions to the patient. In order to leave the responsibility with the person, one must focus on the possibilities that the person still has. Self-direction expresses a focus on the person's own strength, and on human flourishing.

• The whole person. This value is described as a more holistic approach to healthcare, beyond the medical-clinical. GPs who refer to this core value mention practising medicine as an art. Technical skills are needed, but also connectedness, intuition, and a feeling for the "intangible things". Often, a diagnosis starts with a feeling of ambiguity ("not fluff"). These more-than-physical aspects of the person are also described in terms of taking care of the person's soul.

• Give all people access to the healthcare they need, specifically the vulnerable. Some people get lost in the medical system, or do not fit into only one category. They thus do not get the care they need. Every person must have access to the healthcare s/he needs. This value focuses on vulnerable persons who fall through the cracks and loopholes of the medical system and do not receive what they need: people who are poor, less educated, and have fewer skills to express themselves.

5.3 Third question: the effects of passions of the heart on the work experiences of GPs

How do the passions of the heart affect GPs' work experiences? We focus on dealing with negative experiences (stress, emotions, specifically related to human brokenness and vulnerability) and positive experiences (inspiration and motivation). We present the results for each of the core values formulated in section 5.2).

5.3.1 Personal proximity

Passions of the heart can help handle the negative emotions that are part of general practice. Several respondents' stories related to matters of life and death.

I remember very well, during my period in ... I once had a child with sudden infant death syndrome. And so I was called there to a child who was dead in bed. But I didn't know for how long [the child had been dead], so I started CPR. And none of that was successful. And that was incredibly intense.

That is an example of what I mentioned earlier. Why should that child not live to 70 years old? You see the grief of those parents. And I was so upset about that, that I also thought: oh, I hope that I don't come across this often. Because I don't know if I can keep that up, if I come across more situations like that.

At the same time, I also noticed, in the period after that, that the parents had seen how I had tried to resuscitate the child, which was not successful. In the period after that, of course, I was able to offer them guidance, and wondered "How can this happen?", and so on. Then we had some conversations - I visited them a number of times, as I usually did. That was very special. (R4:20)

In the visits and conversations, the GP became very close to the parents, as a fellow sufferer. Not only did this personal proximity help the parents deal with the loss of their child; it also helped the GP handle the emotional stress of the situation. Matters of life and death confront people with the brokenness and vulnerability of human existence. GPs cannot do anything about that, in a strictly medical sense. However, they can show that they understand how the person feels. This also gives meaning and deep satisfaction to the practitioner, strengthening him/her so that s/he can handle stressful situations.

A passion such as personal proximity can also be a source of moral indignation and moral criticism. The next GP feels what is at stake from the core value of close proximity, and acts on the basis of this passion of the heart.

There was a young woman there. I had just started on gynaecology, I worked there. And that was the first child she would have. And it didn't progress. She was on the intravenous drip for nearly 48 hours. And men were not allowed to be there. That woman was left alone - all the time. And then I would sit with her and have a chat. And I thought, what is this? And then the staff, the nurses and gynaecologists - especially the nurses - thought it was ridiculous for me to sit next to that woman and have a chat and help her get through. (R1:32)

Passions have a deep power to act, but also to criticise existing situations and to transform these situations (as far as it is within the agent's power to do so).

The stories of the GPs clearly show that the passion of personal proximity is a deep source of agency for GPs. The next story is that of a GP reporting on giving help and guidance to young people in crisis:

The most satisfying things are perhaps when guiding young people in crisis. Young people who are in crisis, it can be anything: anorexia, depression, or ... whatever. And if you can contribute to that, so that they overcome this illness ... Because there, you can be supportive from your own life experience ... Often it is the case that you try to give them the optimism to just get through it. . There is always a turn, an opportunity in life. (R3:19)

In some situations, a practitioner has nothing else to give to support someone but his/her humanity. In this case, it is the GP's life experience that there will always be a turn in circumstances or a new opportunity in life. The GP as a person becomes the main "instrument" of agency.

Finally, we also observe that the core value of personal proximity is a source of inspiration and motivation. In the words of one GP:

No, no. You cannot suddenly become a different person. At least, that would mean to me that I become a different person. (R2:10)

Later he calls it "an extension of who I am as a person" (R2:13). The same GP reported that, in practice, he sometimes deviates from his motivation to stand close to people, because some people need a more dominant approach. But he does not like doing that. (R2:11)

As a source of inspiration, passions of the heart help GPs deal with the long hours that come with the profession. If they are close to this source, they can deal with it.

So I want to be a warm physician who radiates attention to and compassion for the patients. And I think that's what a patient deserves. And also, that personal continuity. . I think I have worked many hours for my patients. Anyway, I felt really good about it. (R4:10)

5.3.2 Self-directedness of the person

The heart of the core value of self-directedness is trust and confidence in the capacity of people to make decisions regarding how they want to lead a good life with and for others. The GP gives information so that they can make a decision themselves.

If you understand why you have pain in your back, and that nothing [necessarily] needs to be broken, you can deal with it better. And I try to stimulate that very much. So yeah, I don't know, how do you say that? Just let people keep control. (R5:35)

In reflecting on the question of whether she could be a GP without this core value, she indicated that her ultimate intention is to keep the person in control. Nevertheless, she also said that she is inclined to take over control to a certain degree when people are no longer capable of directing themselves - for example, due to a serious illness, or depression.

But if I could never do it again, let people keep their own direction, I would stop immediately. (R5:17)

She could not be a GP if she was not able to work from a position of using this passion for the person's self-directedness as a source of inspiration and motivation.

5.3.3 The whole person

This core value goes beyond the clinical treatment of the patient and includes the meaning of the disease for the person, the strengths and needs of the person, his/her participation in social life, his/her context, and the possible support available to him/her. Embracing a holistic perspective gives a GP access to more information to use in dealing with a person's quality of life. Employing this core value, a practitioner is inclined to observe a situation in a way that goes beyond the clinical perspective.

There was a man who had been very ill for a long time and was also very tired. And it was about to end. Actually, he knew he was going to die. But he remained very restless. . Somehow I had the feeling that there was something else that troubled him. And where that feeling came from, I have no idea. Sometimes you suddenly have things like that. And, well, then [at a certain point] I thought: I'm not getting it [that feeling] anymore. What is this? (R1:31)

Following her gut feeling or intuition, she discovered that this man had had a disagreement with his brother. After some conversation, he found peace, and was able to let go of life. It is important to note, in this instance, that the practitioner was able to act on the basis of this value in a way that extended her capacity to deal with the person's situation. It is also important to see that this was the result of bringing in her own humanity as a source of seeing, knowing, and feeling.

The GPs indicated that this passion helps them deal with their workload. It is a kind of paradox: on the one hand, because of this passion they spend more hours performing their professional services. On the other, this same passion gives them the strength to carry on and endure long working hours.

I want to be a warm physician who radiates attention to and compassion for the patients. And I think that's what a patient deserves. And also, that personal continuity. . I think I have worked many hours for my patients. Anyway, I felt really good about it. (R4:10)

5.3.4 Give all people access to the healthcare they need, specifically the vulnerable

We found that the stories of our GPs mainly reported contrast experiences (for example, about brokenness and vulnerability).

Very recently, there was a 50-year-old woman who had been alcohol addicted for a long time and who continued to sink further into addiction; she had also had a depressive episode and wanted to do away with herself. And she had been hospitalised with severe liver inflammation, so it was really serious. But she just couldn't stop drinking. If you are addicted, you cannot stop. . And I had not managed to get addiction care, they always pushed it to mental health care. They said: no, no, she is depressed because she uses alcohol. . And then I received a letter from . the health insurance company, saying no, the company did not purchase enough, we cannot help this patient. (R1:33)

In her definition, vulnerable people are those who get "lost" in the medical system, in the sense that they do not get the healthcare they need. The core value of this GP is a source of moral indignation and criticism.

That injustice, and also that hiding behind all kinds of rules. Where professionals do not see people, but only hide behind rule. (R1: 33)

She wants that the needs of a person are what decisions are based on, not the rules and protocols. Putting the needs of people first is a passion of the heart, which she recognises in other physicians: "I thought: oh, what bliss - there is someone with a heart!" (R1:3)

6. CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

What can we conclude, on the basis of our research, about the passions of the heart of general practitioners? Three research questions were formulated. The conclusion to the first question is that some concerns of GPs can be characterised as passions of the heart, with the following four characteristics: fulfilment (transcending; human flourishing); receptivity (being apprehended); a life-organising power, and an ethical nature. Some concerns are final ends, which can be distinguished from passions of the heart, because they lack two markers: transcending and receptivity. Final ends can be marked by a life-organising and ethical nature. We will return to this finding in the discussion (below).

The conclusion to the second research question is that four core values could be identified in the concerns of the GPs: personal proximity; self-direction; the whole person, and to give all people access to the healthcare they need, specifically the vulnerable. These are all person-related values that are part of the so-called humanistic approach to healthcare.

The conclusion to the third research question is that passions of the heart mitigate the effect of negative experiences (emotional stress and burnout) and inspire and motivate GPs in their work. We expected this finding, because of the quality of passions of the heart as meta-intentional strivings. We will elaborate on this finding in the discussion (below).

Finally, we want to discuss two remarkable findings. The first extraordinary result was the fact that some concerns were only characterised by a life-organising power and ethical nature. The markers of transcendence and receptivity (being apprehended) were not mentioned, in some concerns. For this reason, we defined them as final ends, and not as passions of the heart. Final ends are marked by intentionality: they are feasible and manageable. Passions of the heart are defined as meta-intentional strivings in the life of the spirit, as

the mutual interpenetration of spiritual and felt processes and the configurated whole of human existence that rests upon this interpenetration (Strasser 1977:199).

Passions refer to purposes that are fulfilling, but not to be fulfilled by human power (not feasible), and they are received (not manageable). This casts doubt on the effect of a goal-setting intervention programme that aims to find a purpose in life (Schippers 2017:9). Goal-setting is the level of intentionality; purpose or meta-intentionality. It would be interesting to study the effect of this type of intervention programme using our measuring instrument of passions of the heart. We hypothesise that the life goals formulated by students in these programmes are final ends and not passions of the heart.

Secondly, we found that passions of the heart mitigate the effect of negative experiences (emotional stress and burnout) for GPs, on the one hand, and inspire and motivate them, on the other. According to the theory, passions of the heart transform people by lifting them up to the level of the spirit (purpose), and the essence of this transformation is a restoration of freedom, versatility, and world governance. This experience of more freedom, versatility and world governance was not part of our research. We suggest that new research on passions of the heart should include this aspect of the restoration of freedom, versatility, and world governance. In terms of purpose, GPs gain freedom to choose and change goals, to deal with not reaching goals, and to find new goals (specifically humanistic values). New research should find evidence of this transforming power of passions of the heart.

Finally, we formulate the study limitations of our research. Our explorative research included six GPs, sampled using a snowball method. The strength of our findings is limited to this restricted number and sampling method. New research should focus on a larger sample (30-40), using an a-select sampling method.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Babbie, Ε. 2008. The basics of social research. 4th edition. Belmont, CA: Thomson.

Des Ordons, L.R., De Groot, Α., Rosenal, J.M., Vioeer, N. & Nixon, L. 2018. How clinicians integrate humanism in their clinical workplace - "Just trying to put myself in their human being shoes". Perspectives on Medical Education 7:318-324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0455-4

Engberg-Pedersen, T. 2012. Logos and pneuma in the Fourth Gospel. In: M.M. Mitchel & D.P. Moessner (eds), Greco-Roman culture and the New Testament (Supplements to Novum Testamentum 143) (Leiden: Brill), pp. 27-48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004226548_004 [ Links ]

Glas, G. 2018. Persoonsgerichte zorg (Person-centred care). In: B. van Engelen, G. van der Wilt & M. Levi (eds), Wat is er met de dokter gebeurd? (Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum), pp. 161-167. [ Links ]

Hermans, C.A.M. 2019. Everything can change. A response to my conversation partners. In: C.A.M. Hermans & K. Schoeman (eds), Theology in an age of contingency (Münster: LIT Verlag), pp. 173-191. [ Links ]

Hermans, C.A.M. 2020. A battle for/in the heart. How (not) to transform the heart. In: J.A. van der Berg & C.A.M. Hermans (eds), A battle for the heart (Münster: LIT Verlag), (in press). [ Links ]

Hermans, C.A.M. & Anthony, F.V. 2020. On the high sea of spirituality. Antecedents and determinants of discernment among school leaders in India. Acta Theologica (in press). [ Links ]

Huber, H. & Jung, H.P. 2015. Een nieuwe invulling van gezondheid, gebaseerd op de beleving van de patient: "Positieve gezondheid" (A new interpretation of health, based on the patient's perception: "Positive health"). Bijblijven 31:589-597. DOI: 10.1007/s12414-015-0072-7;589 [ Links ]

Huber, M. 2011. Health: How should we define it? British Medical Journal 343(7817):235-237. [ Links ] Joas, H. 2016. Do we need religion? (The Yale Cultural Sociology Series). Place of publication?: Taylor and Francis. (Kindle edition). [ Links ]

Karr, S. 2019. Avoiding physician burnout through physical, emotional, and spiritual energy. Current Opinion in Cardiology 34(1):94-97. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0000000000000574 [ Links ]

Landis, J.R. & Koch, G.G.1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159-174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310 [ Links ]

Morenammele, J.M. & Schoeman, J. 2020. Christian leadership in workplaces: Exploring parachurch organisations in Lesotho. Acta Theologica Supplementum 30:86-112. [ Links ]

Movir 2012. Rapport landelijk onderzoek naar langdurige stressfactoren bij huisartsen [Report National research into long-term stress factors in GPs]. LSJ Medisch Projectbureau. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://movir.nl/arbeidsongeschiktheidsverzekering/huisarts/ [5 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Schippers, M.C. 2017. IKIGAI: Reflection on life goals optimizes performance and happiness. ERIM Inaugural Address Series Research in Management. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/1765/100484 [5 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Strasser, S. 1977. Phenomenology of feeling. An essay on the phenomena of the heart. Translated by E.Wood. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press. [ Links ]

Swart, M.J. 2015a. 'n Narratiewe teologiese verkenning van negatiewe koronêre vatomleidingsoperatsieuitkomste: 'n Chirurgiese hermeneutiek. Acta Theologica 35(2):120-141. https://doi.org/10.4314/actat.v35i2.8 [ Links ]

Swart, M.J. 2015b. The spiritual experience of a surgeon. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 100(1):376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.054 [ Links ]

Tallon, A. 1992. The concept of the heart in Strasser's phenomenology of feeling. American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly 64(3):341-360. [ Links ]

Underwood, L. 2011. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Overview and results. Religions 2:29-50. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2010029 [ Links ]

Van de Brand, J. 2016. Levensverhaal en pedagogische handelingsoriëntatie in de laatmoderne tijd. Een kwalitatieve survey onder leraren in het Nederlandse katholieke basisonderwijs. Münster: LIT Verlag. [ Links ]

Van de Brand, J., Hermans, C., Scherer-Rath, M. & Verschuren, P. 2015. An instrument for reconstructing contingent interpretation of life stories. In: R. Ganzevoort, M. Scherer-Rath & M. de Haardt (eds), Religious stories we live by. Narrative approaches in theology and religious studies (Leiden: Bril), pp. 104-112. [ Links ]

Van den Muijsenbergh, M. 2018. De huisarts kan het verschil maken. Gezondheidsverschillen en persoonsgerichte, integrale zorg door de huisarts [The general practitioner can make the difference. Health differences and individual, integrated care by the general practitioner]. Bijblijven 34:190-198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12414-018-0299-1 [ Links ]

Van Luijn, H. & Maalsté, N. 2016. The role of ideals in professional life. In: G. van den Brink (ed.), Moral sentiments in modern society: A new answer to classical questions (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press), pp. 227-256. [ Links ]

Wachholtz, A. & Rogoff, M. 2013. The relationship between spirituality and burnout among medical students. Journal of Contemporary Medical Education 1(2):83-91. [ Links ]

Wiederhold, B.K., Cipresso, P., Pizzioli, D., Wiederhold, M. & Riva, G. 2018. Intervention for physician burnout: A systematic review. Open Medicine 13:253-263. DOI: 10.1515/med-2018-003 [ Links ]

Date received: 15 September 2020

Date accepted: 8 October 2020

Date published: 23 December 2020

1 Morenammele & Schoeman's (2020) research into this issue also belongs to this second type.

2 See Hermans & Anthony (2020) in this journal.

3 In this instance, Strasser uses Logos in the sense in which it is used in ancient Greek philosophy and early Christian theology referring to the divine reason implicit in the cosmos, ordering it and giving it form and meaning (https://www.britannica.com/topic/logos). For an introduction to the relationship between "pneuma" ("spirit") in the Gospel of John and "logos" ("word" or "mind") in the prologue of John, see Engberg-Pedersen (2012).

4 A basic transcending awareness can also be expressed in the form of mystical awareness, contemplative reverie, or the playful cultivation of an aesthetic ideology (Strasser 1977:294).

5 For an extended account of passions of the heart, See Hermans (2020) (in press).

6 On the other hand, Strasser (1977:295) stresses that this "being apprehended" is always at the same time a "letting-oneself-be-apprehended".

7 Each quote in Atlas.ti has a unique reference: R5:24 refers to Respondent 5, quote 24.