Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.40 suppl.30 Bloemfontein 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.Sup30.6

ARTICLES

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.Sup30.6

A next generation? Young Dutch Reformed Church ministers and their vision for the church in South Africa

Dr. G.J. van Wyngaard

Department of Philosophy, Systematic and Practical Theology, University of South Africa. (orcid.org/0000-0003-1607-4736) E-mail: vwynggj@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

For the foreseeable future, the Dutch Reformed Church will be remembered for its role in the theological justification of apartheid and spiritual support for the leaders driving this political process. Questions on the faith, theology, and spirituality that made this theological and spiritual support possible have been analysed in detail over decades. This church is, however, poised to see a generation of ministers, who were trained after the Dutch Reformed Church's position on apartheid changed, and after the end of apartheid in South Africa, taking over the leadership of this denomination. This article analyses responses to a 2019 survey among Dutch Reformed Church ministers and licensed proponents aged younger than forty years. Utilising a 7-point praxis matrix, it highlights the way in which these respondents describe the current ecclesial praxis and discern the future calling of the church. It focuses particularly on how they relate to the church's past, and its historically White identity.

Keywords: Dutch Reformed Church; Apartheid; Reconciliation; Mission; Spirituality

Trefwoorde: NG Kerk; Apartheid; Versoening; Sending; Spiritualiteit

1. INTRODUCTION

During the 1970s and early 1980s, a surge in ministerial candidates and ensuing licensing and ordinations resulted in a distorted age distribution among ministers in the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) (Dutch Reformed Church Task Team Research 2019). The current effect is that ministers over the age of fifty-seven years (in 2019) constitute 40% of all ordained ministers linked to congregations, while 23% are under the age of forty years.1 The DRC is, therefore, poised for a sudden change in the composition of its congregational ministers in terms of age and gender (Dutch Reformed Church Task Team Research 2019).2 Simultaneously, the DRC retains into the present its historic ethnic and racial character as a white Afrikaans church.

In preparation for the 2019 General Synod of the Dutch Reformed Church, an extensive survey was conducted among all licensed proponents and ministers of the DRC under the age of forty years.3 While there have been surveys of DRC ministers over the years, these have been randomised samples that reproduce the age and gender distribution of ministers in general. This survey of specifically younger ministers provides an important lens on the views of ministers who represent the clergy of the future, while also increasingly stepping into leadership positions in local congregations, the broader denomination, and representing the DRC within broader ecumenical and societal networks.

In this article, four open questions from this survey are analysed in seeking to better understand the vision for the church and Christian life that this group of younger ministers will bring to the church and society in the coming years. The analysis highlights a shift in the understanding of what the calling of the church in society should be and relates this to broader questions in terms of its ongoing work of facing the apartheid past of the DRC and the inter-generational inequalities brought about by racial injustice.

2. RESEARCH DESIGN

2.1 Research questions

In order to study the potential leadership role of younger ministers of the DRC, the following research questions were formulated:

• How do younger ministers in the DRC interpret the current identity and role of the DRC in the country and local communities?

• How do younger ministers in the DRC understand the calling of this church within the Southern African context?

• What vision do younger ministers in the DRC have for the future of this church?

2.2 Sample and data collection

In 2019, four hundred and forty-two people under the age of forty years were licensed in the DRC. In all instances, where correct contact details were still available, they were invited to participate in the survey. Invitations were sent on behalf of the DRC Task Team Research by email and WhatsApp. In response, two hundred and forty-three (55%) indicated their willingness to participate, and one hundred and seventeen completed the survey - 26% of all licensed proponents under the age of forty years and 48% of those responded positively to the initial request. The survey consisted of fifty-three questions, of which only a selection is explored in this article. It was completed between 3 and 5 September 2019 as part of the preparation for the 2019 meeting of the DRC General Synod.

2.3Interview instrument

This article draws primarily on the responses to a series of open questions that formed part of the survey:

• Describe the identity of the Dutch Reformed Church as a denomination in one sentence (V1) [Beskryf die identiteit van die NG Kerk as denomi-nasie in een sin].

• Describe the calling of the Dutch Reformed Church for the next five years in one sentence (V2) [Beskryf die roeping van die NG Kerk vir die volgende vyf jaar in een sin].

• The Dutch Reformed Church plays an important role in the country (V3). Please give reasons for your answer (V4) [Die NG Kerk speel 'n belan-grike rol in die land. Gee asb redes vir jou antwoord].

• My congregation plays an important role in the community (V5). Please give reasons for your answer (V6) [My gemeente speel 'n belangrike rol in die gemeenskap. Gee asb redes vir jou antwoord]

Responses to these questions were coded, using a general inductive approach using Atlas.ti. Categories were created, using an iterative reading of the responses, with the responses to each question coded separately (Thomas 2006; Nieuwenhuis 2007:107-109).

V3 and V5 had three options: yes, uncertain, or no. V4 and V6 are, therefore, read in relation to responses to the prior questions. In this analysis, I focus on the reasons given by those who did indicate that the church, at large, and the congregations of which they are part are playing an important role in the country - those who responded "yes" to V3 (65%) and V5 (72%). Brief reference is made to other questions, and even other surveys, where it serves to illuminate the responses to these four questions.

2.4 Interpretive framework

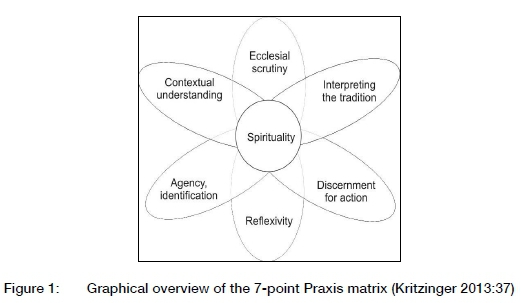

In the argument below, I utilise the praxis matrix, as developed in the discipline of Missiology at the University of South Africa (Unisa),4 as an evaluative framework in reading the responses. I specifically draw on the 7-point praxis matrix developed by Klippies Kritzinger (2008). The centrality of spirituality and the general emphasis on praxis in relation to an ecclesial community and its discernment for future action made this appropriate for the broader project on leadership and spirituality, of which this article forms part.

While Spirituality (7) ties together the various points of the praxis matrix, there is no hierarchy between them, and the resemblance to the petals of a flower is a reminder that all seven aspects of the praxis matrix are interrelated, and that these continuously impact on each other in the development of a particular praxis. When used as an instrument of analysis, the value of the praxis matrix lies in the way in which it reminds the researcher of the multifaceted aspects that inform the praxis of an individual or group. Where not all aspects can receive equal attention, as is the case below, it highlights where further analysis is required. The sections on Ecclesial scrutiny (3), Interpreting the tradition (4), and Discernment for action (5) are closely intertwined and form the heart of my analysis. The discussion under Reflexivity (6) and Spirituality (7) will, in part, deepen this analysis, by focusing on the tension that emerges in this middle section - a tension between ministers' descriptions of the church's calling, on the one hand, and of the reasons for its current importance, on the other.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Agency

Key to understanding the praxis of any group is an understanding of who they are and how they view their own position and relationship to other actors. Kritzinger (2013:38) describes this as Agency, framed by questions such as "Who are the actors? How do they position themselves in and identify with a community?". While this could be approached from multiple perspectives, my interest, in this instance, is primarily in how respondents understand themselves as licensed and ordained individuals in relation to a particular denomination and community of faith they are called to lead.

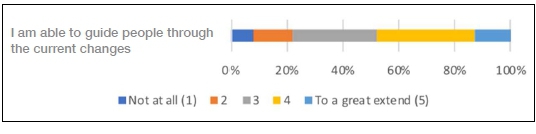

A number of important points can be raised from the responses, of which 97% mentioned that the DRC will still exist in twenty years' time, with the majority of them (72%) indicating that it will take on a different form.5 Of the respondents, 74% indicated that they believe that they will still be in ministry twenty years or more from now. While it was a formal connection to the DRC that initiated the invitation to participate, the responses also indicate a strong sense of seeing an ongoing involvement with and commitment to the DRC - for the majority of their working lives at least. They also described themselves as mostly competent in leading people through the current changes.

This provides but a single lens focused on how young ministers view themselves within the DRC. Yet this is key in terms of the main question regarding what their leadership role might be in the coming years.

3.2 Contextual understanding

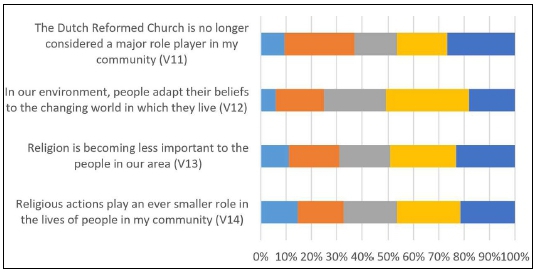

Context is again a multifaceted notion, which can focus on political, economic, social, or cultural factors (Kritzinger & Saayman 2011:5). In this instance, I focus on one aspect, namely understanding the importance of religion, in general, and churches, in particular, in contemporary society. In a series of questions broadly related to what might be described as secularisation, the general trend is towards reporting the decreasing importance of religion in society. These questions focus on what respondents think the perceptions of society at large are towards religion and the DRC.

When asked whether they think that the DRC, in general, and their local congregations, specifically, play an important role in the country, the response was overwhelmingly positive. To put this into stark perspective, when first asked whether their congregation plays an important role in their community, 72% answered "yes" (V5). When later asked whether they agree with the statement that "The Dutch Reformed Church is no longer regarded as an important role player in my community", the trend was clearly towards agreement (V11).

The tension between a general perception that other people perceive a decreasing importance of religion in society, combined with a particular sense of the importance of specific expressions of the local congregation, seems to point towards an understanding that, while religion might not be considered important, they themselves perceive that the concrete expression of their church plays an important role in society. Young ministers still think that the DRC plays an important role in South Africa.6

3.3 Ecclesial scrutiny

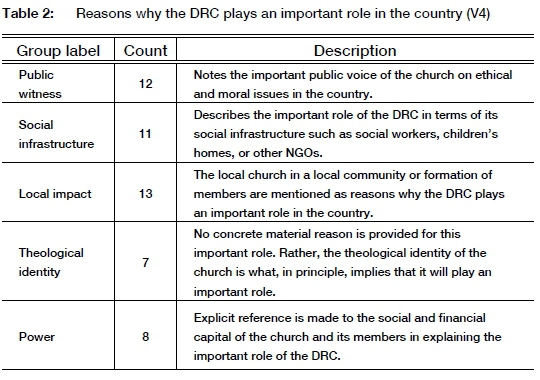

Ecclesial scrutiny (Kritzinger 2013:38), sometimes described as ecclesial analysis (Kritzinger 2008:771), refers to how respondents describe the church, and its past actions, in particular. In this instance, I focus first on responses regarding the identity of the DRC, and then on responses to the reasons for the important role the DRC plays in the country and communities.

When speaking of the identity of the church, multiple interpretations of the notion are possible. Are we speaking of an ideal identity, who the church should be, or describing who the church is? Are we speaking of a theological identity or a social identity? Are we describing the empirical reality of the church, or the normative identity of the church, when asked to respond to the identity of the church (Ormerod 2018:2)?

While some overlap does occur, respondents typically chose an interpretation of what the question on identity would refer to, with some describing it in more social, and others in more theological terms.

One strong theme that emerges is that of uncertainty concerning its current identity. That the DRC is a broad organisation has often been commented on, and both positive aspects on diversity and tying identity more critically to ongoing divisions are observed.

The main theological and social threads that emerge in terms of identity have clear links to the responses that will be discussed below. The primary theological identity was related to the church being sent into the world -various understandings of the church in mission. While not entirely absent, an emphasis on witness is less frequently described with explicit reference to missional identity than might be expected.8 An identity concerning the witness or mission aspects is instead expressed through the language of being "called" [geroep] or "sent" [gestuur]. This was far more common than references to a Reformed identity, or what might be described as a more typically evangelical description of a church tied to the Bible. On the other hand, the ethnic and racial identity of the church is critically questioned, and a more general criticism of the DRC's ongoing relationship to its past is also notable.9

The cluster of responses related to power is of particular interest and importance. It explicitly highlights what may manifest in hidden ways elsewhere. Stated in its most direct form, the DRC plays an important role because "[w]e carry a lot of social and financial power" [Ons dra baie sosiale en finansiële mag]. Another respondent explicitly harks back to discourses on a particularly white responsibility, burden, or simply obviously important role based on the fact of being white: "It is still one of the largest white churches in the country. How can it not play an important role" [Dis nog een van die grootste blanke kerke in die land. Hoe kan ons anders as om 'n rol te speel].10

Such explicit references to racial, social, or financial power remain in the minority, but another dominant response raises the question of the historic relationship with the past and social and financial power in a more benevolent form. The DRC's vast social infrastructure, in terms of social workers, children's homes, and other social institutions, is often mentioned n reference to the important role the DRC is playing.

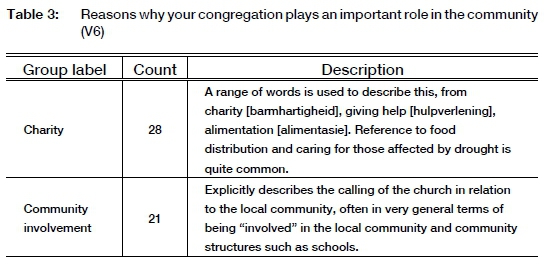

While the importance of the DRC in the country, at large, is closely linked to public witness and social infrastructure, the importance of the local congregation in the local community is overwhelmingly linked to discourses of charity and general community involvement. In both instances, there is a clear sense that this involves the community, at large - beyond the members of the church, but also beyond the White Afrikaner community typically forming the local congregation. These two clusters of responses were mentioned with much greater frequency than all the other ways in which young ministers motivate their position regarding the important role the local congregations play in the community.11

In analysing the 2006 surveys of congregations, Schoeman (2012:5) already noted that the ways in which the DRC is involved in communities are through ad hoc welfare and development projects, with hardly any evidence of working towards more sustainable policy or social changes in the long run. Even now, young ministers report the same reality; the general description by young ministers of the local church's role in the community more than a decade later remains largely unchanged.

The picture that emerges is one where young ministers are critical of the DRC's historic ties to apartheid and segregation, as well as its ongoing White racial character. However, they note the church's vital social impact in the present through its historic social infrastructure and the charity work of local congregations and members. I return to the implications of the ways in which this latter emphasis is tied to the White identity, which it also criticises below.

3.4 Interpreting the tradition

Who we are, how we read our context, and how we understand the community shape a particular local theology (Kritzinger & Saayman 2011:5). A specific understanding of the Christian tradition emerges when we analyse the praxis of a community. In this instance, a few themes emerge more strongly from these responses than a drive towards acting in communities. The calling of the church (V2) is overwhelmingly directed towards the community at large,12 and less to the congregation, specifically, or towards God, more generally.13 In describing what they consider the DRC's calling to be for the coming five years, eleven themes were identified.

While some young ministers will focus the calling of the church on an exclusive faith identity (Strong faith identity) or inwardly on members only (Care), the general thrust of responses is very explicitly outwardly focused towards society, in general. Considering these as dimensions of mission,15we note classic dimensions in terms of evangelism and justice, together with public witness, and particularly reconciliation. In terms of calling, this focus on the broader community is, however, often described in more vague language related to mission and being involved in communities.

Reconciliation is a clearly dominant priority for younger ministers and often overlaps with an emphasis on justice. In its most explicit form, a respondent stated: "I think the calling of the DRC is at heart to genuinely live out Jesus' message of reconciliation" [Ek dink die roeping van die NGK is om ten diepste Jesus se boodskap van versoening werklik uit te leef]. Another respondent clearly linked the calling for the future to the pain of the past, and used the language of healing and joining a broader South Africa: "To face her painful history seriously enough to proclaim and practise a healing theology, as a dedicated part of South African society" [Om haar pynlike geskiedenis ernstig genoeg op te neem om genesende teologie te verkondig en beoefen, as toegewyde deel van die Suid-Afrikaanse samelewing].16

This strong emphasis on reconciliation in describing the calling of the church is essential in relation not only to the critical description of ethnic exclusivity when describing the identity of the DRC, but also to the absence of this theme in identifying the current role of the local congregation. I will return to this later. While respondents described reconciliation as a core calling and priority, it is far less visible in their reflections of what the church, at large, or the local congregation is currently contributing to the country or local communities.

There were also clear clusters focusing on evangelism, public witness, and caring for people. Evangelism was used quite overtly to speak of actions that draw people into the Christian faith or the church; public witness refers to a church response to broader societal issues, while caring for people is mostly directed inwards to the members of the local congregation.

3.5 Discernment for action

Without denying the intertwined nature of theological reflection and discernment for action, the question must shift somewhat to ask how the emerging theology of mission, described above, takes form in descriptions of envisioned action. Of particular concern, in this instance, are the continuities and discontinuities between respondents' descriptions of the current practice of the church, and their interpretation of what the church should be doing. How do they perceive the actions that should emerge in the future?

First, while the language of community involvement used in describing the current importance of local congregations overlaps with how the church's calling in the coming five years is described, the same is not true concerning the strong discourse on charity. Charity is part of what is considered the important role of local congregations, but the language of charity does not inform how the calling of the church is described.17

Secondly, there is a convergence between public witness as a calling for the coming five years and public witness as a marker of the important role the DRC plays in the country at large. However, public witness is seldom related to the critical role of the local congregation. When briefly reflecting on the public theology of Rondebosch United Church, De Gruchy (2007:32-33) reminds us that the local congregation can indeed be a key site and community of public witness,18 and this observation is important: the role of this congregation was the result of decades of formation. The question must be asked: Do younger ministers also consider public witness as something that belongs to the task of the local congregation?

Thirdly, perhaps one of the key tensions in the responses is found between how the church's calling in the coming five years is defined, and how the DRC's current role in the country and congregations in communities is described. As noted, a focus on reconciliation, specifically in terms of racial reconciliation, tied to a critical interrogation of the ethnic character of the DRC and its dubious role under apartheid, on the one hand, and a focus on questions of justice in broader society, on the other, are strong emphases in descriptions of calling and priority. However, these do not repeat in descriptions of the critical role of the church at large or local congregations. Only two respondents identified working for reconciliation as an important contribution, in which their congregations are already involved.

From this research, the question of the leadership role that a younger generation of DRC ministers wishes to - and will - play in terms of disrupting White ethnocentric communities and working against racism will remain and warrants further exploration. Yet their own responses indicate a shifting priority from the church's current role towards an emphasis that remains outstanding. In this discontinuity between the church's calling and her current role, the potential leadership of a generation of young ministers might be noted.

3.6 Reflexivity

Kritzinger and Saayman (2011:6) summarise the reflexivity lens of the praxis matrix as follows:

What is the interplay between the different dimensions of the community's mission praxis? Do they succeed in holding together these dimensions of praxis? How do they reflect on their prior experiences and modify their praxis by learning from their mistakes and achievements? How do all the dimensions of praxis relate to each other in these agents of transformation?

This lens draws out some tensions that emerge from the discussion thus far. I first want to highlight the leadership challenges that emerge from these tensions, and name some of the silences that might create longer term challenges for this generation of ministers to confront.

As stated, tension emerges between reflections on the church's calling versus descriptions of its current practice. While young ministers were prone to draw on the language of reconciliation and justice in describing the DRC's calling in the immediate future, what they described as the local congregations' involvement in communities can mostly be typified as "charity". The problem is not unique to the DRC. Bowers du Toit and Nkomo (2014:8) remind us that

[t]he charity and 'ad hoc' approaches employed by congregations in addressing poverty within South Africa, whilst well-meaning, do not acknowledge the structural nature of the system of poverty and inequality engendered by apartheid.

On the other hand, they proceed to name local clergy as the primary contributor in cases where congregations did move beyond charity towards processes to "restore the socio-economic injustices".

Although a minority voice, two respondents indicated that their congregations were not playing an important role in the community, and they attributed this to the congregations' focus on charity.19 They recognised the involvement of the congregations in the community, but did not view this as leading to an important role, due to the kind of involvement.

We help a few people with their immediate needs without addressing the major broken systems in dependence on Christ. (V6) [Ons help 'n paar mense met hulle onmiddellike behoeftes sonder om in afhanklikheid van Christus die groot gebroke sisteme aan te spreek.]

This must be related to the tension that remains between the acknowledgement of the DRC's role in past injustice, critical description of its present ethnic identity, and the way in which current and future positive contributions to the country rely on these very matters.

Earlier, I described one thread that links the important role of the church explicitly to the power and wealth of its members, or even to the mere fact of being white. While such explicit identifications of power, being the reason for the DRC not playing a significant role in the country, are the exceptions, a more implicit reliance on historic assets and infrastructure is, in fact, the norm. One of the most common reasons given to why the DRC plays a positive role in the country is its social infrastructure through social workers and aid organisations.

A key question that would need to be worked out by this generation of leaders in the DRC is how to relate their commitment to questioning the whiteness and ethnic identity of this church, with their simultaneous investment in the historic structures of social upliftment that are heavily indebted to the very same racial privilege. The question is how to dislodge the strong emphasis on being sent to the world from its White and middle-class moorings, in order to allow for a vision of being called towards justice, which is informed by true solidarity with those on the margins of society.20

Let me conclude this reflection by returning to the dimensions of mission emerging from this analysis and speaking from the silences. Because I align with Kritzinger's position that local circumstances should determine the dimensions of the mission that congregations and groups of Christians highlight (Kritzinger 2013:37), it is of interest to note what does not appear. Bevans and Schroeder (2011:64) identify six dimensions of a mission:

• witness and proclamation;

• liturgy, prayer and contemplation;

• justice, peace and the integrity of creation;

• dialogue with women and men of other faiths and ideologies;

• inculturation, and

• reconciliation.

Witness and proclamation, justice - with peace implied,21 but with hardly any emphasis on the integrity of creation22 - and reconciliation are clear themes emerging above. Liturgy, prayer and contemplation, dialogue with women and men of other faiths and ideologies, and inculturation receive hardly any explicit attention.

The absence of dialogue with women and men of other faiths and ideologies and inculturation deserves some reflection. Despite one set of responses noting what can be described as a generally secularising tendency in society, where public witness is mentioned, the assumption still seems to be that a Christian voice can indeed speak into the South African public sphere and be heard. South Africa remains a nominally Christian country, and the need to develop competencies in dialoguing with those who bring fundamentally different convictions to the table is not indicated as a priority for the near future.

On the other hand, young ministers are critical of the white ethnic character of the DRC and express a desire to work towards reconciliation. But what this implies in terms of the complex dynamic of white people embedding themselves thoroughly within an African context remains out of reach in these responses. In this instance, perhaps, we are confronted with the limitations to which a church - that remains for all intents and purposes white in contemporary Southern Africa - can indeed pursue a deeper inculturation of its theology within the African context, regardless of its stated commitment to this context.

Lastly, the lack of a strong emphasis on liturgy, prayer and contemplation, as linked to a dimension of mission (separate from witness and proclamation), should be noted. I return to this in the last section.

3.7 Spirituality

By placing spirituality at the centre of the praxis matrix, Kritzinger and Saayman (2011:4) remind us that a spiritual motivation distinguished Christian action from other forms of activism. In analysing the praxis of a community, we could ask about the spirituality that informs its action; but, in planning, we could also ask about the spirituality that would need to underlie a community's praxis. I want to touch on both these aspects briefly.

Following the above argument, it should come as no surprise that one of the strongest themes emerging from respondents is that faith and the issues in the country should be related to each other. Of the respondents, 74% indicated that they definitely agreed: "Believers of all churches should stand together to build our country" (V7) [Gelowiges van alle kerke behoort saam te staan om ons land op te bou], whereas respondents simultaneously strongly rejected statements that separate personal faith and the "issues in the country" - "Faith is about my personal relationship with God and not about issues in the country" (V8) [Geloof gaan oor my persoonlike verhouding met God en nie oor kwessies in die land nie] and "The congregation should focus on my personal faith and not on issues in the country" (V9) [Die gemeente moet fokus op my persoonlike geloof en nie op kwessies in die land nie].

To put this into perspective in terms of the changes within the church, the distinct difference between young ministers and congregants, in general, should be noted.23 The 2018 National Church Life Survey posed these same two questions (V7 and V8) to congregations, with overwhelming agreement on the first, and an unsure response on the second (Schoeman 2019b). Young ministers' overwhelming emphasis on faith and religion that finds expression in life, in general, is not articulated in the same way by the congregants whom they are called to minister.24 Perhaps, in this tension, they will find part of their own calling and task in the years to come.

However, the question of how Christian faith may be drawn upon to critically transform white identities is of particular importance in the present. In a detailed analysis of several young white Christians in the Gauteng area, Schneider (2017:139-145) indicated how the historic mission trajectory of the church in South Africa, the DRC in particular, are being reformed in projects of white self-transformation. While there is a long history of white commitments to anti-racism erupting from encounters with black people through activities of mission, the ways in which these activities reproduce historic racial logics should not be underestimated (Van Wyngaard 2014b).

4. SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

In this study, I analysed young ministers and licensed proponents of the DRC's responses to questions concerning the identity, vision, and current role of the DRC, by employing Kritzinger's praxis matrix. By noting differences between their descriptions of past identity, present action and future vision, we can see a generation of leaders envisioning a change of direction for the DRC, while also being caught up in fundamental contradictions inherited from the past.

In respondents' ecclesial scrutiny, interpretation of the tradition, and discernment for action, there is a continuation of the long mission history of the DRC. However, distinct shifts are also visible. It does not take the form of "mission to the ends of the earth",25 but has a very strong emphasis on local communities. This emphasis was repeated in descriptions of the calling and priority for the future, as well as the role that the church, at large, and local congregations, are playing in the present. In terms of the current practice, respondents mentioned a church that plays an important role in the present, but largely describe this with language that can be related to acts of charity, and often tie this directly to privilege and power related to past injustices. On the other hand, they describe the calling of the church in the language of reconciliation, justice and the kingdom of God. In terms of the spirituality underlying this praxis, it primarily commits to social transformation as a spiritual task (Sheldrake 2012:78).

While forming the mission practice of the church in ways that will be consciously committed to local communities, one important challenge facing this generation of leaders will be how to accompany local congregations being transformed: from how they are currently described as living out the envisioned calling, forming White Christians committed to charity as the ways in which they engage with their broader community, to a reconciled community that can seek justice together as equal members of local communities.

A key tension that then emerges is between the simultaneous critique of the church's apartheid past ethnic and racial identity, on the one hand, and reliance on the privilege and power inherited from this past when envisioning the future, on the other. The social infrastructure presented as a source of the positive contribution that the DRC makes in the present is one example, while the more explicit reliance on the financial and social capital of members is another. As stated, at times, this still takes the form of a "white man's burden", or a moral and social function explicitly tied to a White identity within Africa.

As pointed out, there was a general absence of any strong emphasis on liturgy, prayer and contemplation in the calling of the church. The dominant discourse is one of "going out" and "making a difference",26 with notions of justice, reconciliation and public worship similarly positioning the DRC as the acting subject. There is, as mentioned, a critical discourse on the ethnic and racial character of the church, and its historic ties to apartheid. However, if one challenge in terms of spirituality and leadership that emerges, in this instance, involved drawing a broader church into a spirituality that is deeply committed to action, a second challenge that remains largely unexplored in the responses received involves the kind of spirituality that would allow this grappling with White complicity and ties to historic injustice. It requires the kind of change that Rieger (2004) described "in-reach" - allowing encounters to transform who we are, which in itself is but a preparation for the deep spiritual work of facing the terror of whiteness in ourselves that Perkinson (2004:117) explores. If the task of leading a church so thoroughly intertwined with the history of White supremacy is taken up, it will require not merely a commitment to society, in general, but a spirituality that can sustain an anti-racist commitment over generations (Massingale 2017). One respondent, quoted above, anticipated this interdependency when making a connection between facing a painful past, in order to practise a healing theology. However, facing such a dark past is a particularly spiritual discipline that requires cultivation and formation. Whether this task will be taken up, and the ways in which this task will be taken up by this generation of clergy, remain to be explored. In this instance, the challenge of leadership and spirituality will perhaps meet its ultimate test for those called into ministry in the DRC.

While the disruption of an apartheid theology and ecclesial practice in the DRC has been a task taken on by congregational ministers for decades, the generation poised to step into a greater leadership role in the DRC in the coming years envisions continued engagement with the implications of its ongoing ethnic and racial character. A clear vision on how to guide congregants to draw from their Christian faith in critically disrupting their White racial and racist formation still needs to be outlined. Most importantly, while the language of reconciliation plays a key role in the discourse of young ministers, their understanding of this notion and how it relates to an anti-racist practice require further investigation. At the same time, ongoing research into the ways in which such a vision is worked out in local ecclesial praxis would be needed in the coming years.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Benadé, C.R. & Nlemandt, C.J.P. 2019. Mission Awakening In The Dutch Reformed Church: The Possibility Of A Fifth Wave? HTS Teologies Studies/Theological Studies 75(4), a5321. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5321 [ Links ]

BEVANS, S. & SCHROEDER, R.P. 2011. Prophetic dialogue: Reflections on Christian mission today. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 2004. Transforming mission. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Botha, J. & Forster, D. 2017. Justice and the missional framework document of the Dutch Reformed Church. Verbum et Ecclesia 38(1), a1665. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v38i1.1665 [ Links ]

Bower du ToiT, N.F. & Nkomo, G. 2014. The ongoing challenge of restorative justice in South Africa: How and why wealthy suburban congregations are responding to poverty and inequality. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70(2), a2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i2.2022 [ Links ]

De Gruchy, J. 2007. Public theology as Christian witness: Exploring the genre. International Journal of Public Theology 1(1):26-41. https://doi.org/10.1163/156973207X194466 [ Links ]

Dutch Reformed Church 2019. Kerkorde van die Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://kerkargief.co.za/doks/acta/AS_KO_2019.pdf [21 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Dutch Reformed Church Research Task Team 2019. Veranderende predikanteprofiel en aftree-ouderdom. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://ngkerk.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Taakspan-Navorsing-Predikanteprofiel-en-aftree-ouderdom-finaal.pdf [19 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Headley, S. & Kobe, S.L 2017. Christian activism and the fallists: What about reconciliation? HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 73(3), a4722. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4722 [ Links ]

Jennings, w.J. 2010. The Christian imagination: Theology and the origins of race. London: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Kourie, C. 2009. Spirituality and the university. Verbum et Ecclesia 30(1):148-173. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 2008. Faith to faith - Missiology as encounterology. Verbum et Ecclesia 29(3):764-790. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. 2013. Mission in prophetic dialogue. Missiology: An International Review 41(1):35-49. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, J.N.J. & Saayman, w. 2011. David J. Bosch. Prophetic integrity, cruciform praxis. Dorpspruit: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Massingale, B.N. 2017. Racism is a sickness of the soul. Can Jesuit spirituality help us heal? [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society/2017/11/20/racism-sickness-soul-can-jesuit-spirituality-help-us-heal [19 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Nell, I. 2019. Buite die grense van die bekende: Kruiskulturele ervarings onder 'n ewekansige steekproef predikante in die NG Kerk. Stellenbosch Theological Journal 5(3):495-513. https://doi.org/10.17570/stj.2019.v5n3.a23 [ Links ]

Niemandt, C. 2010. Kontoere in die ontwikkeling van 'n missionêre ekklesiologie in die Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk - 'n Omvangryker vierde golf. Nederduitse Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif 51(3&4):92-103. [ Links ]

NlEUWENHUIS, J. 2007. Analysing qualitative data. In: K. Maree (ed.), First steps in research (Pretoria: Van Schaik), pp. 99-122. [ Links ]

ORMEROD, N. 2018. Social science and ideological critiques of ecclesiology. In: A. Paul (ed.), The Oxford handbook of ecclesiology (Oxford: Oxford University Press). DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199645831.013.16 [ Links ]

Perkinsün, J.W. 2004. White theology: Outing supremacy in modernity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

RlEGER, J. 2004. Theology and mission between neocolonialism and postcolonialism. Mission Studies 21(1):201-227. [ Links ]

Saayman, W. 2007. Being missionary being human: An overview of Dutch Reformed Mission. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Schneider, R.C. 2017. The ethics of whiteness: Race, religion, and social transformation in South Africa. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Houston, TX: Rice University. [ Links ]

SCHOEMAN, W.J. 2012. The involvement of a South African church in a changing society. Verbum et Ecclesia 33(1), Art. #727, 8 pages. [ Links ]

SCHOEMAN, W.J. 2019a. The voice of the congregation - A significant voice to listen to. Stellenbosch Theological Journal 5(2):473-488. [ Links ]

SCHOEMAN, W.J. 2019b. Evaluating congregational life in post-apartheid South Africa - A case study. Paper delivered at the 35th Biennial ISSR Conference, 9-12 July 2019, Barcelona, Spain. [ Links ]

Sheldrake, P. 2012. Spirituality: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

StatsSA 2011. Census 2011: Census in brief. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.statssa.gov.za/census/census_2011/census_products/Census_2011_Census_ in_brief.pdf [9 May 2020]. [ Links ]

The Kairos Theologians 1985. The Kairos document and commentaries. Geneva: World Council of Churches. [ Links ]

Thomas, D.R. 2006. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation 27(2):237-246. [ Links ]

Van Wyngaard, G.J. 2012. Race-cognisant whiteness and responsible public theology in response to violence and crime in South Africa. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Van Wyngaard, G.J. 2014a. The language of 'diversity' in reconstructing whiteness in the Dutch Reformed Church. In: R.D. Smith, W. Ackah & A.G. Reddie (eds), Churches, blackness, and contested multiculturalism: Europe, Africa, and North America (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), pp. 157-170. [ Links ]

Van Wyngaard, G.J. 2014b. White Christians crossing borders: Between perpetuation and transformation. In: L. Michael & S. Schulz (eds), Unsettling whiteness (Oxford: Inter-Discplinary Press), pp. 191-202. [ Links ]

Date received: 7 July 2020

Date accepted: 1 September 2020

Date published: 23 December 2020

1 All general demographic data are from the central General Competency Council database, except where indicated that it is from the survey being analysed.

2 In 2019, only four women ministers over the age of fifty-seven years were linked to DRC congregations, 0.75% of ministers in this age group, while 36% of the candidates licensed as ministers and 32% of the ministers ordained in the DRC from 2005 onwards were women.

3 This refers to ministers who would have entered theological studies after the end of legal apartheid, in 1997 at the very earliest, who would have been ordained at the earliest in 2003. The year 2004 showed the lowest number of new licensees in the DRC since 1959, dropping to sixteen from an all-time high of one hundred and seventy-one in 1981. Since then, there has been a steady increase until 2011, and a slight decrease thereafter.

4 For a brief overview of the various versions, see Kritzinger & Saayman (2011:3).

5 There was no direct question on what form this would take. Some of the responses analysed below do indicate what kind of church they might envision.

6 In some instances, the role of the DRC is also clearly exaggerated. One respondent described it as the "largest church in South Africa", while there is a long list of larger denominations in South Africa. Another stated that it represents two-thirds of the White Afrikaans population, while formal membership numbers of eight hundred and fifty thousand and nine hundred thousand would indicate that this is below 40%, and probably closer to 30% of the approximately 2.7 million White South Africans who speak Afrikaans as a first language (StatsSA 2011:26).

7 This survey was completed shortly before the 2019 General Synod, at a time when public debate in the church was highly polarised in terms of issues of sexuality.

8 The DRC Church Order is quite explicit in its use of missional terminology. In the 2019 Foreword, for example, it states that "With this Church Order ... give expression to the church's missional calling" ["Met hierdie Kerkorde ... uiting te gee aan die kerk se missionale roeping"] (Dutch Reformed Church 2019:ii), and article 2 of the church order was explicitly developed as a statement of a missional identity. "Missional" or its derivatives are, however, only used four times when responding to the identity of the church and, in one case, it is used in the negative, stating that it is "a church that has a lot to say and write about being missional, but struggles to move out of its comfort zone and past its church walls". ["n Kerk wat baie sê en skryf oor missionaal wees, maar sukkel om uit sy gemaksone en verby sy kerkmure te beweeg.]

9 Some brief responses include "volkskerk" (V1), the idea of a church existing with a particular ethnic focus, or "White and Afrikaans" [Blank en Afrikaans]. The latter, but without the clearly negative emoticon, were used a number of times as description of the identity. Other respondents added to this reference the "last bastion" of Afrikanerdom.

10 While this could be read as a political statement of being a church for a White minority, other responses from the same respondent qualify this as drawing from a different trajectory in DRC racial politics - that of the White missionary. The same respondent twice emphasises a focus on the broader community, beyond the membership of the local congregation - first as a key factor they consider when applying at a congregation, and again as one of the key priorities the DRC should have, in order to live up to their calling in this context.

11 Smaller clusters of notions that have already been outlined in relation to other questions include caring - specifically for members (6), forming members (6), crossing and expanding borders (7), social infrastructure (6), evangelism (2), reconciliation (2), justice (1) and community development (3), which is distinct from the more general involvement in the community.

12 This idea is repeated in a later question from the survey, to which I do not pay detailed attention in this study: "What three priorities should the Dutch Reformed Church take to fulfil its calling in the present context?" (V15) [Watter drie prioriteite moet die NG Kerk stel om haar roeping in die huidige konteks uit te voer?]. In this instance, priorities are also directly related to the well-being of society at large.

13 While some responses such as "Life in salvation focused on Christ alone" [Lewe in verlossing gefokus op Christus alleen] defined the calling of the church in language that was purely focused on God, these were a small minority.

14 The significance of this description is further highlighted when compared to the general ministers' panel of May 2020. This was a randomised sample with eighty-five respondents, of whom 20% were under the age of forty years. V2 from young ministers' panel was repeated, but the word "kingdom" only appeared once, in this instance.

15 I have in mind Bosch's "mission as" (Bosch 2004), which Kritzinger (2013:36) describes as "dimensions".

16 The language of reconciliation in itself is not innocent. Jennings (2010:10) speaks of its "terrible misuse in Western Christianity", and the Kairos Document famously indicated the problematic way in which a certain thread of theologies make reconciliation into an absolute principle which, in practice, serves to perpetuate injustice (The Kairos Theologians 1985:17-18). Such a critical interrogation of reconciliation continues into the present (Headley & Kobe 2017), and its prominence among young White ministers of the DRC could, and should, undoubtedly be probed further. On the other hand, in spite of a critical interrogation, the notion will remain important for Christian theology (as a careful reading of all three of these mentioned critical sources would remind). Within the context of what remains one of the most racially homogeneous institutions in South Africa, it also signals a conviction on what requires attention that should be noted. In this study, I accept the language utilised by respondents in describing what they discern the calling of the church to be, without too quickly reading into this language any particular usage of the notion. On the other hand, we must remain conscious of how the language of reconciliation has historically often signalled a White rejection of calls for racial justice, restitution, and strong interventions aimed at a more equal society. Exploring, in more detail, what is implied with "reconciliation" in DRC discourse is important.

17 The May 2020 survey, with a randomised sample of ministers, confirms the significance of this shift. In the survey, "service" [diens] was the key term used in describing the calling of the church in the coming five years. This concept is almost entirely absent in the responses to V2, in this instance, occurring only once, and then clearly being a reference to forms of charity - bringing relief.

18 In this instance, "public witness" follows the code mentioned thus far, but De Gruchy (2007:33) describes this as "public theology as Christian witness".

19 The vast majority of the respondents who mentioned that congregations are not playing an important role in the community gave as reason the congregation's inward focus or focus on survival only.

20 Botha & Forster (2017) analyse how the formal Missional Framework Document of the DRC reflects its origin in a similar position of power and privilege, raising the same question to the DRC.

21 The DRC has a long and infamous history of sanctioning state violence. In spite of its own strong response to violence in the South African society (Van Wyngaard 2012), the extent to which deliberate peace theologies are part of the repertoire of congregational ministers of the future requires further investigation.

22 The silence on ecology is somewhat surprising, given the place of this priority with the formal structure of the DRC, both in the General Synod and in various regional synods. In V15, where three priorities were identified per respondent, the environment is named only twice in the three hundred and forty-three priorities named.

23 That ministers and congregants in the DRC have distinctly different perspectives is also noted in other places. Schoeman (2019a or b?:483-484) notes diverging understandings between congregants and ministers on how they view the Bible.

24 Congregants seem to reveal a spirituality that assumes some dichotomy between faith and life, while ministers are seeking a spirituality intertwined with all of life (see Kourie 2009:154).

25 Saayman (2007) identifies this as his fourth wave of DRC mission in his published overview of Dutch Reformed Mission. Niemandt (2010) included such a local emphasis in a possible expansion of Saayman's fourth wave. Benadé and Niemandt (2019) later included this in a description of a possible fifth wave. This shift towards a more local emphasis in Dutch Reformed mission is not in itself new. However, what is striking in these responses is a total absence of priority for global mission among younger ministers, while a randomised sample of all ministers in 2018 still highlighted the importance of international outreach for intercultural experiences in the DRC (Nell 2019:508, 511). One respondent made it quite explicit that a key priority of the DRC should be to "send fewer missionaries abroad" (V15) [Minder sendelinge na buiteland stuur]. The same respondent includes as another priority "Join hands with local congregations and organizations" [Hande vat met plaaslike gemeentes en organisasies]. While this requires further research, these responses seem to indicate a fundamental break with Saayman's fourth wave, which coincided with the end of apartheid and the first years post-apartheid.

26 "Making a difference" [verskil maak] was often the explicit term used in what was captured above under a general "Mission" category in the calling of the DRC.