Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.40 n.2 Bloemfontein 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v40i2.17

ARTICLES

Re-imagining the congregation's calling - Moving from isolation to involvement

W.J. Schoeman

Prof. W.J. Schoeman Department Practical anc Missional Theology, University of the Free State. (orcid.org/0000-0003-2454-9658); schoemanw@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Congregations need to re-imagine their calling in their movement from isolation to involvement. Congregations need, from a theological perspective, to answer the question: What is the calling of the congregation? The calling or mission of the congregation provides purpose, direction, and meaning to congregational life. The theoretical understanding lies in a movement in congregational life from isolation towards involvement. The aim is to place congregational life on a continuum, with a limited interaction of the congregation with the environment, on the one hand, and open and engaged interaction of the congregation with the environment, on the other. What is the empirical or contextual position in which congregations find themselves? It is possible to imagine a movement for congregations towards the future. In imagining a movement towards the future, a congregation needs to engage with attitudes and practices that facilitate such a movement.

Keywords: Congregational studies, Re-imagining, Calling, Involvement, Future

Trefwoorde: Gemeentestudies, Verbeelding, Roeping, Betrokkenheid, Toekoms

1. INTRODUCTION

Congregations are communities where believers in the triune God meet and celebrate their relationship and serve their Lord. Their purpose and aim may be formulated as a calling to proclaim the gospel in this specific age and time. This proclamation is a commission for every congregation, but the specific context challenges the way in which this is done.

Doing theology is a committed enterprise and an engaged faith-praxis, taking the here and now seriously; it is more than simply studying theology (De Gruchy 2011:10). Re-imagining is doing theology as a transformative theological praxis that

address[es] the personal, social and political realities that we associate with overcoming injustice and the legacies of apartheid, and creating a society and a world in which human life and the environment can flourish (De Gruchy 2011:13).

The question is: How should congregations answer their call to ministry nowadays?

In trying to re-imagine the calling of the congregation, the following four questions or statements need to be discussed:

• The theological question: From a theological perspective, what is the calling of the congregation?

• The theoretical understanding lies in a movement in congregational life from isolation towards involvement.

• What is the empirical or contextual position in which congregations find themselves?

• Would it be possible to imagine a movement for congregations towards the future?

A look at the painting Las meninas (1656) by the Spanish artist Diego Velazquez may help us re-imagine the current congregation's calling (Serban 2013:42).1 The word menina means "lady-in-waiting" or "maid of honour", i.e. a girl who serves in a royal court. Las meninas by Pablo Picasso is a series of fifty-eight paintings by Picasso in 1957. He did a comprehensive analysis of, reinterpreted and recreated Velazquez's Las meninas several times. In May 1968, Picasso donated the series to the museum in Barcelona, stating:

If someone wants to copy Las Meninas, entirely in good faith, for example, upon reaching a certain point and if that one was me, I would say ... what if you put them a little more to the right or left? I'll try to do it my way, forgetting about Velazquez. The test would surely bring me to modify or change the light because of having changed the position of a character. So, little by little, that would be a detestable Meninas for a traditional painter, but would be my Meninas.

Some critics argue that each image in the painting by Picasso (Serban 2013:44-45) was considered from two diametrically opposite sides - good and evil. For example, the two characters in the lower right-hand corner of the painting, which, at first glance, seem to be unfinished, are a dog and a boy, Nikolasito. On the one hand, they can symbolise aggression and anger. On the other hand, a dog can be considered a white innocent creature, but the boy projects his childhood and spontaneity.

Picasso's painting Las meninas is not easy to understand. It is a complex and controversial philosophical work with many symbolic meanings. It is also a vivid example of how work can transform the famous master whose thinking and vision, devoid of barriers, and imagination are subject only to unlimited creative freedom. Picasso was able to create a completely new reality to reveal the secret with which he trusted the audience.

When I saw this series of Picasso in Barcelona in June 2019, I was struck by the way in which this master reinterpreted the work of Velazquez. It reminded me of the hermeneutical process of reading a text - be it a written text or a context - and of reinterpreting it to give meaning to a new and changing context. The first step would be to reflect on the congregation's calling.

2. THE CALLING OF A CONGREGATION

In the development of a practical-theological ecclesiology, two important aspects need to be borne in mind, namely a theological description of the congregation and an analytical framework to give an empirical description of the congregation (Schoeman 2015a). In this section, the discussion focuses on the theological description of the congregation. Burger (1999) and Van Gelder (2000) identified three important components in the theological understanding of a congregation: identity, mission, and ministry of a congregation.

Although congregations are social organisms where people belong, communicate with one another, and live in social relationships, they are fundamentally communities of faith that form their identity in relationship with the triune God. The congregational identity is shaped by a confessional relationship between the triune God and the members of the congregation (Nel 2015:44-46). This defines the character of the community of faith.

The calling or mission of the congregation gives purpose, direction and meaning to congregational life. The congregational calling is a consequence of the identity of a congregation. The mission of a congregation is to proclaim the gospel and attest to the work of Jesus Christ. A congregation has a single missional purpose (Nel 2015:106-117), which Flett (2010:kindle edition) describes as "announcing the kingdom of God is the community's great and simple commission, her 'opus proprium'". The witness of the Christian community is about what God has done through Jesus Christ and is intimately connected with "God's cosmic-historical plan for the redemption of the world" (Guder 2000:58). Bosch (1991:54) made the following profound statement on the calling of the congregation:

The New Testament witnesses assume the possibility of a community of people who, in the face of the tribulations they encounter, keep their eyes steadfastly on the reign of God by praying for its coming, by being its disciples, by proclaiming its presence, by working for peace and justice in the midst of hatred and oppression, and by looking and working toward God's liberating future.

The calling of the congregation is grounded in the work and nature of the triune God:

The Father sent his Son and Spirit into the world, and this act reveals his 'sending' being. He remains active today in reconciling the world to himself and sends his community to participate in this mission (Flett 2010:kindle edition).

The calling or mission of the congregation is not a secondary act or an activity to follow later, if needed; it is

grounded in Scripture, the apostolic act constitutes the being of the community. If the community fails to live her life of missionary service, which is the nature of her fellowship with God, then she does not live in the Spirit and cannot be Jesus Christ's community (Flett 2010:kindle edition).

The calling of the congregation is directly linked to the being of the congregation.

The calling of the congregation draws together, informs and forms the ministry of the congregation. The ministry of the congregation includes all the activities of being and doing that form part of congregational life (Burger 1999:104). The ministry of a congregation plays out in four dimensions of congregational life: leitourgia, kerugma, koinonia, and diakonia (Schoeman 2002:67-92). These four dimensions "are all essential dimensions of the Spirit-enabled witness for which the Christian church is called and sent" (Guder 2000:53). The congregation is called to minister in its specific context to people living in this world.

The identity, calling and ministry of a congregation are embedded in the context of the congregation. The interaction between congregational life and context could be understood on different levels of commitment and involvement. A theoretical perspective is essential, in order to describe this interaction.

3. ISOLATION AND INVOLVEMENT - A THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE

Congregational life is complex and can be understood through different theoretical lenses. As an open social system, a congregation is part not only of a local community, but also of the society and the global world. The interaction and engagement with the environment may differ from congregation to congregation. The aim of this theoretical perspective is to place congregational life on a continuum, with a limited interaction of the congregation with the environment, on the one extreme, and an open and engaged interaction of the congregation with the environment, on the other. This proposed perspective should be viewed as the provisional development of a theoretical framework.

A congregation that views itself as isolated from its environment or that wants to isolate itself from the world may be described as a closed system. The emphasis is on the internal processes and management of the organisation. The congregation views itself as self-contained, with the main emphasis on its internal life (Van Gelder 2007:126). The congregation could regard itself as an island or sanctuary. Sanctuary congregations, as an extreme example, seek to live in isolation from this world and its temptations and emphasise the world to come (Ammerman 1999:339). Another way of describing isolated congregations is to use the term "enclavement". An enclave differentiates itself from other groups, in order to create internal cohesion; some are "in" and others are "out" (Cilliers 2012:504). Congregations may function fairly well as enclavements or safe havens away from a diverse and complex world.

"Isolated" congregations emphasise care for their membership and maintenance of the congregation for the sake of the membership. The identity of the congregation is defined in terms of perseverance and the building of internal cohesion. Maintaining and developing the bonding capital within the community of faith are an important priority. The needs of individual members are important and the leadership focuses on task competency as a leadership style (Osmer 2008:176). The critical question for "isolated" congregations is: To what extent is it possible to fulfil the calling of the congregation?

The other extreme of the theoretical continuum may be described as a more involved understanding of the interaction between congregation and community. From an open system perspective, there is a dynamic relationship and interaction between the congregation and its larger context (Van Gelder 2007:135). The congregation is able to adapt as a learning system and recognise the importance of being flexible and able to respond to changes in its environment (Van Gelder 2007:139). There is an openness and engagement between congregation and community.

Cilliers (2012:504-506) draws on the work of Volf (1996:140-147) to describe four movements to move out of the enclave into embracement. The first movement entails opening one's arms as an invitation to create a space for the other to come in. The second movement is to wait patiently and to listen. This illustrates the desire to engage and not a powerful movement to break the boundaries. The third movement is a reciprocal act of embracement, the closing of the arms.

In this embrace the identity of the self is preserved and transformed, and the alterity of the other is affirmed and respected. (Cilliers 2012:505)

The fourth movement is the opening of one's arms again. The movement of action out of safe spaces asks of congregations to uphold the following values: crossing borders towards the "other"; respect human dignity; urgency of transparency and honesty; need for dialogue and reciprocal teachability, and inclusion of the marginalised (Cilliers 2012:506). The four movements may help congregations become more involved, but this is not an easy journey.

The movement to involvement is a vulnerable position. According to Koopman (2008:246), the church serves a vulnerable God and consists of vulnerable people who ask for a vocation and mission determined by the notion of vulnerability. Faithfulness to the calling of the congregation implies that the church recognises its vulnerable essence and "means that we fulfil our calling in all walks of life in the mode of vulnerability" (Koopman 2008:254).

Congregations that are open to their context seek partnerships that build bridges and value bridging and linking capital. They are oriented towards including the "other" and the vulnerable in their ministry. They value transformational leadership (Osmer 2008:177-178), and view leadership as

a new kind of Christian and theological leadership was actually needed, empowered by different skills and theological contents and able to lead the churches towards new modes of meaningful engagement in society (Swart 2008:108).

These congregations are open to cultural diversity and care for the society. They create open and safe spaces for dialogue and interaction between different cultural groups within the congregation and the community (see Mostert 2019).

This theoretical perspective may help place congregations on a continuum between isolation and involvement. This would challenge the congregation's understanding of its calling. It is, however, also necessary to examine whether, from an empirical perspective, it is possible to place congregations on the continuum.

4. AN EMPIRICAL POSITIONING OF THE CONGREGATION2

To navigate to a new location, one needs to identify one's current position and work on the strategic steps to be taken, in order to move to a new and more preferred position. The empirical positioning and understanding of a congregation are, therefore, of significant importance in the re-imagining of the calling of a congregation. Time and limited space make it impossible to undertake a comprehensive empirical analysis of congregational life. However, the aim of this section is to identify a few markers that may function as guidelines in positioning congregational life between isolation and involvement.

An analytical framework is essential for an empirical description of the congregation. Congregations may be described in terms of their relationship with their context; the external interaction between congregation, the local community, and the broader society and congregations may be analysed in terms of their internal life, the functioning and organisational structures of the congregation (Schoeman 2015a:78-79). Both aspects will be used in the empirical description of congregational life. The Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) will be used as a case study and the results of two quantitative surveys, namely the 2018 Congregational Survey3 and the 2018 South African National Church Life Survey (SA-NCLS),4 will be discussed.

The results from the 2018 Congregational Survey may be used to give a general positioning, in which the DRC congregations are currently finding themselves. In order to do so, the financial situation and the direction of the congregations are used as variables:

• The financial situation in which congregations And themselves (see Table 1): Congregations are finding themselves in an increasingly serious declining financial situation (in 2018, 63.9% were in decline or in serious trouble).

• The direction in which the congregation is moving (see Table 2): Congregations are finding it increasingly difficult to survive. The majority of them are busy with maintenance (in 2018, 63.5% were shrinking or busy with maintenance).

This would indicate that those congregations that are busy with maintenance and struggling financially would be more inclined to be busy with building-up and maintaining the congregation than being actively involved in the community.

The 2018 SA-NCLS gives a voice to the membership of the DRC. This is an important voice to listen to and to understand where the DRC and her congregations are currently positioned through the eyes of ordinary members, or attendees, in this instance.

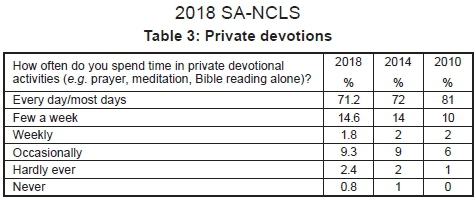

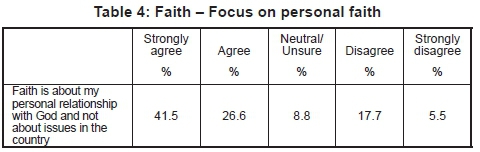

The first focus is on the internal faith and spiritual life of the attendees and their position:

• Daily private devotions (see Table 3) (in 2018, 71.2%) are an important part of the spiritual life of attendees.

• Faith is about their personal relationship with God and not about issues in the country (see Table 4); 41.5% strongly agree with this statement.

• Involvement in the wider community (see Table 5). The attendees are not involved in evangelistic, outreach, or community activities (91.4 % said "no"), or in community service, or other social or welfare activities (76.7% said "no").

The attendees significantly emphasise their personal and private religious activities and are not actively involved in the wider community. This may be an indication of an emphasis on the private and personal expression of their faith.

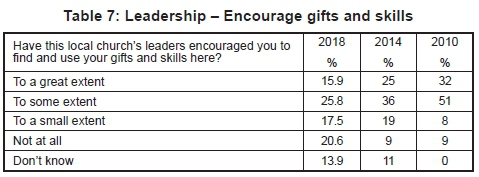

The second focus is on the evaluation of congregational life, with specific reference to the inspirational core qualities of the congregation as evaluated by the attendees:

• A clear and owned vision (see Table 6). Less than a third (27.6%) of the attendees are aware of, and strongly committed to the goal and direction of the congregation.

• An inspiring and empowering leadership culture (see Table 7). Only 15.9% of the attendees feel, to a great extent, that the leadership encourages them to use their gifts and skills.

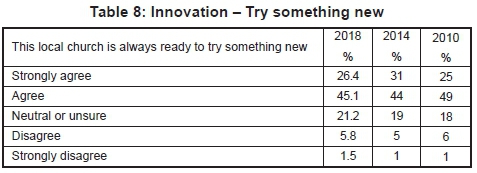

• Imaginative and flexible innovation (see Table 8). The attendees are open to the congregation trying something new; over two-thirds of them agree or strongly agree.

The attendees need a vision to be committed to, and a leadership style that encourages them to use their gifts and skills. They are open to innovation. These three inspirational core qualities may be used to re-imagine future attitudes in practices in the congregation.

The third focus is on reconciliation. Since 1994, South Africa remains an unequal and deeply divided society. Reconciliation could and should have played an important role in healing these divisions. Since 2003, the South African Reconciliation Barometer (SARB) is measuring the extent of reconciliation in society. Table 9 reports on the progress made since 2011 in terms of reconciliation:

Just over half the population, however, feel that progress in terms of reconciliation has been made, while fewer than half of South Africans report having experienced reconciliation themselves. Reconciliation processes are taking place in a context of economic uncertainty, declining confidence in institutions and low political efficacy (Potgieter 2017:51).

The 2018 SA-NCLS asked the same question as the SARB used (see Table 10). The attendees, to a lesser extent than the general South African population, are of the opinion that progress has been made in reconciliation since the end of apartheid. South African society needs progress in terms of reconciliation; unfortunately, this is not happening. The church could play an important role in this regard (see Table 11), as the attendees strongly indicated.

The empirical lens indicates that the DRC congregations tend to be more on the isolation extreme of the continuum, due to the focus on maintenance and the financial constraints they experience. More important to note is that the attendees experience a lack of clear vision and that the leadership should encourage them to be involved in an innovative way in the challenges facing the South African society. Would it be possible to re-imagine the calling of congregations and their members to a changing and challenging context?

5. IMAGINING A MOVEMENT TOWARDS THE FUTURE

In imagining a movement towards the future, Brueggemann (2001:116) proposes a prophetic ministry that is offering an alternative perception of reality in letting people view their own history in light of God's freedom and his will for justice. This involves an understanding of who God is. In doing trinitarian theology, creativity and variety could be described as an imaginative construction that leads to new understandings and possibilities.

A certain vocabulary which has become associated with the recent discourse, for example relationality, communion, generosity, gifting, mutuality, conveys both adventure and constraints, newness and identification (Venter 2010:574-575).

This imagination, according to Venter, responds to the reality of God and is not open for speculation, but an adventure of creative obedience. "The prophetic ministry seeks to penetrate despair so that new futures can be believed in and embraced by us." (Brueggemann 2001:17).

Van den Berg and Ganzevoort (2016) explore the art of creating different futures as a strategic endeavour within the field of practical theology. In this instance, the specific focus is to use their perspectives in formulating and creating spaces for congregations to fulfil their calling. Although the tradition and history of a congregation present part of a historical framework and an empirical analysis evaluates the current context, there is also a need to formulate congregational practices for the future.

Even though we can only live in the present, the act of remembering brings the past into the present, whereas anticipation and imagination bring out the future into the present (Van den Berg & Ganzevoort 2016:168).

Van den Berg and Ganzevoort (2016:177-182) identify three attitudes towards the future that play a role in practical theology, but also in terms of the community of faith.

In the utopian attitude, preferable but not possible, the congregation focuses on telling and dreaming about eschatological stories: How life would be if Christian values are fully actualised. The community of faith surpasses the natural order of human communities by witnessing that an alternative community is a possibility. The church is a family of brothers and sisters who live by the values of the sermon on the mount. The congregation should be a moral and spiritual example to the world. The formulation of a visionary dream for a congregation is thus important. The Reformation is not over and

we indeed dream of a different world together, we may receive and enjoy the imagination and creativity of tomorrow's children (Smit 2017:15).

The prognostic-adaptive attitude focuses on the probable (the preferable is an opportunity and the unpreferable is a threat). The challenge for communities of faith would be to engage with the opportunities and prepare for the future. The context is posing specific challenges to the congregation such as, among others, demographic and cultural challenges, as well as inequality and unemployment. The congregational leadership is challenged to find answers and strategies to meet the challenges with a prognostic-adaptive attitude.

Imagination feeds on listening, learning, and relating to others about all the hurts and hopes of people in our churches and communities.

Without imagination, leadership falters. Imagination requires time to hold significant conversations with others who may not have our experience or perspective (Dyck 2012:130).

This attitude will help leaders identify opportunities and prepare for the future.

The designing-creative attitude, as the possible preferable, envisions what we want to see happen in this world where God's kingdom should be coming. The challenge of this design and innovation category is to develop practices and structures that are possible, but not yet real (Van den Berg & Ganzevoort 2016:176). The congregation and its membership, as a missional and inclusive community, should focus on innovative practices that would lead to an engagement with the community.5

The three attitudes and the practices associated therewith are important markers in re-imagining the future, but the congregation and its members should also explore reading the biblical text as an important and normative practice in re-imagining their calling. I want to use the work of Tolmie (2014)6 as an example and focus on his findings. He suggests the following conclusions for a contemporary interpretation of this text:

• It stirs people's imagination, because the text imagines a world that differs clearly from what people normally experience in everyday life. Furthermore, the text expresses the notion that this other world is not an imaginary one but can become reality by participating in Christ Jesus.

• The text could be classified as an open text; there never has been a single universally accepted interpretation of the notions expressed in the text; not in Paul's time and not even when it still formed part of pre-Pauline tradition.

• The openness could be approached in a positive and self-critical way -do not too easily make decisions on the meaning, seek blind spots, and attempt to widen your horizons.

• A better approach seems to be to deliberately opt for interpreting Galatians 3:28 in such a way that people are included, brought together, liberated, reconciled, and embraced (Tolmie 2014).

In light of the above conclusions, the reading of the text could open new and creative meanings for the congregation to understand its calling.

In reading a biblical text, there should be a sensitivity to the one who is reading the text and with whom they are reading it. In his research, Forster (2017:213-215) worked with a predominantly Black (Coloured) group and a White group that read Matthew 18:15-35 and reflected on their understanding of forgiveness. The Black group understood forgiveness as collective, political and social, while the White group individualised and spiritualised forgiveness as restoring their relationship with God. A facilitated intercultural reading of the text together by the two groups led to a more integral understanding of forgiveness:

the participants were far more open to accepting understandings of forgiveness that were not held within their in-group, but more common among members of the outgroup (Forster 2017:215).

The congregation should include people from diverse backgrounds in reading and reflecting on the meaning of the biblical text.

In imagining a movement towards the future, it is important for the congregation to engage with attitudes and practices that facilitate such a movement.7

The task of the prophetic ministry is to evoke an alternative community that knows it is about different things in different ways (Brueggemann 2001:117).

6. CONCLUSION

The re-imagining of the calling of the congregation could, as a theological starting point, listen to the first two paragraphs of article three of the Belhar confession:

We believe

that God has entrusted the Church with the message of reconciliation in and through Jesus Christ; that the Church is called to be the salt of the earth and the light of the world; that the Church is called blessed because its members are peacemakers, and that the Church is a witness, by word and deed, to the new heaven and the new earth in which justice dwells;

that by the life-giving Word and Spirit God has conquered the powers of sin and death and therefore also of alienation and hatred, bitterness and enmity; that by the life-giving Word and Spirit God will enable the Church to live in a new obedience which can open up new possibilities of life also in society and the world;

The leadership formulates a visionary dream that, in an innovative way, inspires the congregation and its members to live as witnesses of an alternative.

Imagination enables us to give a fresh and meaningful expression to our experiences and helps us

respond to reality in ways that are creative, open and healing, and socially transformative rather than trapped in an unjust and ugly past (De Gruchy 2014:45).

A re-imagination of the congregation's calling will help reform its traditions and ministry towards a meaningful involvement in their context.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ammerman, N.T. 1999. Congregation and community. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 1991. Transforming mission. Paradigm shifts in the theology of mission. New York: Orbis Books. https://doi.org/10.1177/009182969101900203 [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 2001. The prophetic imagination. Second edition. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Burger, C.W. 1999. Gemeentes in die kragveld van die Gees. Stellenbosch: CLF-Drukkers. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J. 2012. Between enclavement and embracement: Perspectives on the role of religion in reconciliation in South Africa. Scriptura 111(3):499-508. https://doi.org/10.7833/111-0-31 [ Links ]

De Gruchy, J.W. 2011. Doing theology in South Africa today. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 139(March):7-17. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, J.W. 2014. A theological odyssey. My life in writing. Stellenbosch: Sun Press. https://doi.org/10.18820/9781920689445 [ Links ]

Dyck, S. 2012. Leadership: A calling of courage and imagination. Journal of Religious Leadership 11(1):113-139. [ Links ]

Flett, J.G. 2010. The witness of God. The Trinity, Missio Dei, Karl Barth, and the nature of Christian community. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. Kindle-edition. [ Links ]

Forster, D.A. 2017. The (im)possibility of forgiveness? An empirical intercultural Bible reading of Matthew 18:15-35. Nijmegen: Radboud Universiteit. [ Links ]

Guder, D.L. 2000. The continuing conversion of the church. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Hermans, C. & Schoeman, W.J. 2015. Survey research in practical theology and congregational studies. Acta Theologica Supplementum 22:45-63. https://doi.org/10.4314/actat.v21i1.5S [ Links ]

Koopman, N. 2008. Vulnerable church in a vulnerable world? Towards an ecclesiology of vulnerability. Journal of Reformed Theology 2(3):240-254. https://doi.org/10.1163/156973108X333731 [ Links ]

Mostert, N.J. 2019. Multiculturalism and urban congregations: The quest for a spatial ecclesiology. Unpublished DTh thesis. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Nel, M. 2015. Identity-driven churches. Who are we, and where are we going? Wellington: Biblecor. [ Links ]

Osmer, R.R. 2008. Practical theology. An introduction. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Potgieter, E. 2017. SA Reconciliation Barometer 2017. Cape Town: Institute for Justice and Reconciliation. [ Links ]

Schoeman, W.J. 2002. 'n Prakties-teologiese basisteorie vir gemeente-analise. Unpublished DTh dissertation. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Schoeman, W.J. 2010. The Congregational Life Survey in the Dutch Reformed Church: Identifying strong and weak connections. Nederduitse Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif 51(3&4):114-124. https://doi.org/10.5952/51-3-85 [ Links ]

Schoeman, W.J. 2011. Kerkspieël - 'n kritiese bestekopname. Nederduitse Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif 52(3&4):472-488. https://doi.org/10.5952/52-3-57 [ Links ]

Schoeman, W.J. 2015a. Exploring the practical theological study of congregations. Acta Theologica Supplementum 22:64-84. https://doi.org/10.4314/actat.v21i1.6S [ Links ]

Schoeman, W.J. 2015b. Identity and community in South African congregations. Acta Theologica Supplementum 22:103-123. https://doi.org/10.4314/actat.v21i1.8S [ Links ]

Serban, O. 2013. Portraying the unrepresentable: "The methodical eye" of the early modern meta-painting. "Las Meninas", from Velazquez to Picasso. Analele Universitatii Bucuresti: Filosofie (2):39-53. [ Links ]

Smit, D. 2017. Hope for even the most wretched. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02280.x. Unpublished lecture. [ Links ]

Swart, I. 2008. Meeting the challenge of poverty and exclusion: The emerging field of development research in South African practical theology. International Journal of Practical Theology 12(1):104-149. doi: 10.1515/IJPT.2008.6 [ Links ]

Thesnaar, C. 2014. Rural education: Reimagining the role of the church in transforming poverty in South Africa. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70(1):1-7. doi: 10.4102/hts.v70i1.2629 [ Links ]

Time Magazine 2019. Volume 193, number 18. 13 May. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://time.com/5581483/time-cover-south-africa/ [16 March 2020]. [ Links ]

Tolmie, F. 2014. Oor die interpretasie van Paulus se uitspraak in Galasiërs 3:28. LitNet Akademies 11(2):331-350. [ Links ]

Van den Berg, J. & Ganzevoort, R. 2016. The art of creating futures - Practical theology and a strategic research sensitivity for the future. Acta Theologica 34(2):166-185. doi: 10.4314/actat.v34i2.10 [ Links ]

Van Gelder, C. 2000. The essence of the church. A community created by the Spirit. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. [ Links ]

Van Gelder, C. 2007. The ministry of the missional church. A community led by the Spirit. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. [ Links ]

Venter, R. 2010. Doing trinitarian theology: Primary references to God and imagination. In die Skriflig 44(3 & 4):565-579. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v44i3/4.162 [ Links ]

Volf, M. 1996. Exclusion and embrace: A theological exploration of identity, otherness, and reconciliation. Nashville, TN: Abingdon. [ Links ]

Date received: 16 March 2020

Date accepted: 13 August 2020

Date published: 18 December 2020

1 For a discussion of the Las meninas, see Serban (2013).

2 Part of this section was presented as a paper "Evaluating congregational life in post-apartheid South Africa" at the ISSR conference, 9-12 July 2019, Barcelona, Spain.

3 For a discussion of the methodology of the Congregational Survey (Church Mirror), see Schoeman (2011) and Hermans & Schoeman (2015b).

4 For a discussion of the methodology of the National Church Life Survey, see Schoeman (2010) and Schoeman (2015b).

5 As an example of what the church can do through rural education, see Thesnaar (2014).

6 "There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus" (NIV). For an exegetical analysis and discussion of this text, see Tolmie (2014).

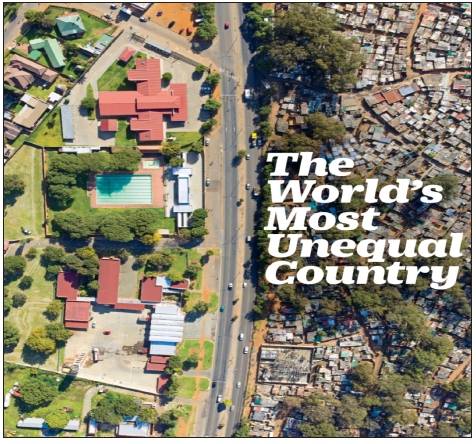

7 The cover page of Time Magazine of 13 May 2019 is a drone photo of the Johannesburg suburbs of Primrose (left) and Makause (right) taken by Johnny Miller. This is part of his drone photographic project called "Unequalscenes", and the aim of the project is to describe in a creative way the world we live in. "We live within neighbourhoods and participate in economies that reinforce inequality. We habituate ourselves with routines and take for granted the built environment of our cities. We're shocked seeing tin shacks and dilapidated buildings hemmed into neat rows, bounded by the fences, roads, and parks of the wealthiest few." (https://unequalscenes.com/south-africa)