Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.39 suppl.27 Bloemfontein 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup27.4

ARTICLES

The Author Of Jeremiah 34:8-22 (LXX 41:8-22): Spokesperson For The Judean Debt Slaves?

M.D. Terblanche

Dr. M.D. Terblanche, Research Fellow, Department of Old and New Testament Studies, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of the Free State, South Africa. Email: mdterblanche@absamail.co.za

ABSTRACT

This article addresses the question as to whether the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 was a voice for the manumitted Judean debt slaves, who were forced back into slavery during a temporary lifting of the siege of Jerusalem during 589-588 B.C.E. Jeremiah 34:8-22 sets the re-enslavement of these slaves as a precedent that explained the fall of Jerusalem in 587 B.C.E. The allusion in Jeremiah 34:14 to Deuteronomy 15:1, 12 does, however, signify that Jeremiah 34:8-22 echoes the "brother ethics" present in Deuteronomy 15:1-18. The author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 shared the "humanitarian" concerns of the debt release and the slave release laws in Deuteronomy 15:1-18. The debt slaves should have been treated as brothers and not as mere objects. He thus became a voice for these marginalised Judeans.

Keywords: Allusion, Jeremiah 34:8-22, Deuteronomy 15:1-18, Manumission of debt-slaves

Trefwoorde: Sinspeling, Jeremia 34:8-22, Deuteronomium 15:1-18, Vrylating van skuldslawe

1. INTRODUCTION

Jeremiah 34:8-9 recounts that king Zedekiah and the people of Jerusalem released their Judean debt slaves during 589-588 B.C.E. Although the motivation for the release is not given, it was probably linked to the circumstances prevailing during the siege of Jerusalem by the Babylonians. Since slaves were normally not subjected to military duty, if they were free, they could be drafted into the army. If the slaves were set free, they would, in a time of food scarcity, have to find their own food (Lundbom 2004:559). However, during a temporary lifting of the siege as a result of the entry of an Egyptian relief force into Judah, the manumitted slaves were brought back into slavery. Jeremiah 34:8-22 sets the re-enslavement of these slaves as a precedent that explained the fall of Jerusalem in 587 B.C.E. (Carroll 1986:650). The dead bodies of the slave-owners, who broke the covenant to free their debt slaves concluded in the presence of YHWH, would become food for the birds of the sky and the beasts of the earth. The king would be delivered into the hands of the Babylonians.

Nonetheless, it is admissible to ask whether the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 did not also act as a spokesperson for the Judean debt slaves. The allusion in Jeremiah 34:14 to Deuteronomy 15:12 has long been recognised. An allusion is a literary device employed by an author intentionally but indirectly to refer to another literary work (Mastnjak 2016:13). It does, however, not only consist in the echoing of an earlier text, but in the utilisation of the marked material for some rhetorical or strategic end (Sommer 1998:15). The humane character of Deuteronomy is well-known. It is especially evident from a comparison of the Deuteronomic torah with the Book of the Covenant (Weinfeld 1972:282-283; Doorley 1994:154-155). For instance, the slave release law in Exodus ordains that the slave must be set free after a six-year period of service, while the Deuteronomic law adds that the manumitted slave must also be provided with gifts, apparently to help his return to private life (Deut. 15:13-14). In addition, the Deuteronomic slave release law avoids the term אדון, "master", since the slave is regarded as an אח, "a brother" of the slave-owner (Weinfeld 1972:283). In contrast to other Ancient Near Eastern laws where the slave is often perceived as a thing, Deuteronomy regards every human being as a person (Tsai 2014:168). This article addresses the following questions: Does the allusion in Jeremiah 34:14 to Deuteronomy 15:12-18 imply that the former text echoes the moral and humanistic character that is displayed in the slave release law in Deuteronomy? Did the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 act as a spokesperson for the Judean debt slaves who did not have a voice of their own?

This article will commence with a look at the allusion in Jeremiah 34:14 to Deuteronomy 15:1-18. Subsequently, it will assess the effect of the allusion to Deuteronomy 15 on the interpretation of Jeremiah 34:8-22. This will finally make it possible to determine whether the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 acted as a voice of the Judean debt slaves.

2. THE ALLUSION IN JEREMIAH 34:8-22 TO THE SLAVE RELEASE LAW IN DEUTERONOMY 15:12-18

Jeremiah 34:8 describes the freeing of the Judean debt slaves by Zedekiah with the phrase לקרוא דרור "to announce a release". The absence of this phrase in Deuteronomy 15 caused some scholars to argue for a literary connection between Leviticus 25 and Jeremiah 34:8-22. However, in Leviticus 25:10, the phrase קרוא דרור occurs in the setting of a jubilee year. In Jeremiah, the phrase is limited to one aspect of the jubilee year, the manumission of slaves (Lemche 1976:52). It is possible that the Holiness Code could have utilised Jeremiah 34 (Leuchter 2008:651). However, since the cognates of דרור appear elsewhere in the Ancient Near East referring to a similar practice of occasional slave release, the authors of Leviticus 25 and Jeremiah 34 could each have drawn independently on a common technical term (Mastnjak 2016:147). Deuteronomy probably avoided the term דרור as a result of its association with the Neo-Assyrian terminus technicus (an-)duraru (Otto 1999:376). For the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22, on the other hand, the Neo-Assyrian power was something of the past (Terblanche 2016:152).

Chavel (1997:92) believes that Jeremiah 34:9b was inserted into an earlier version of the text by a later scribe, who cited Leviticus 25:39, 46b. The phrases at issue in Jeremiah 34:9b are לבלתי עבד בם and ביהודיאחיהו איש. These phrases are neither particularly close to those in Leviticus 25, nor particularly unique. These lexical connections can also be accounted for from the basis of their shared theme rather than to an identifiable literary relationship between Leviticus 25 and Jeremiah 34 (Mastnjak 2016:147-148).

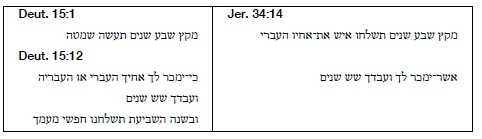

Leuchter (2008:642) is of the opinion that Jeremiah 34:14a is a reference to Deuteronomy 31:9-11 rather than to Deuteronomy 15:1. He nonetheless admits that taken on its own, Jeremiah 34:14a might well be read as a reference to Deuteronomy 15:1 (Leuchter 2008:651). Since Leuchter's view is based on the disputable argument that Jeremiah 34 emphasises the interests and importance of the Levites, it seems sensible to take the opening clause in Jeremiah 34:14, מקץ שבע שנים, "at the end of seven years", as referring to the law announcing the release of debts in Deuteronomy 15:1. The instruction ועבדך שש שנים ושלתו חפשי מעמך, "and he will serve you six years, and you will send him away free from you", points to the slave release law occurring in Deuteronomy 15:12. These laws are linked, since both are concerned with the problem of debt. The defaulting of a loan would eventually lead to the enslavement of a debtor's dependent(s) (Chirichigno 1993:276).

Further evidence for the link between Jeremiah 34:8-22 and Deuteronomy 15:12-18 is evident in the change in Jeremiah 34:14 from second person plural תשלחו, "You [plural] must let go every man his brother", to the second person singular "who may be sold to you (ועבדך) and has served you" (לך) (singular). The later part is in the singular, because the author wanted to quote the verse as it is written in Deuteronomy 15:12 (Weinfeld 1995:153). Despite the fact that different terms are used to refer to the female slaves in Jeremiah 34:9, 11, 16 (שפחה) and Deuteronomy 15:17 (אמה), Jeremiah 34:14 is evidently a paraphrase of Deuteronomy 15:1, 12.

It is noteworthy that Jeremiah 34:14 only calls the recitals of the debt release and slave release laws to mind and not the outworking of these laws. As will be demonstrated, full comprehension of the significance of the allusion can only be attained when the recitals of the laws in Deuteronomy 15:1-18 as well their outworking are considered.

Distinctive to Deuteronomy 15:12 and Jeremiah 34:14 is the pairing of the terms עברי and אח. This is meaningful, since עברי rarely occurs in the Old Testament. In addition, the phrase 'שלח חפשי is used in connection with the manumission of the slaves in Jeremiah 34:14 (and Jer. 34:9, 10, 11, 14, 16) as well as in Deuteronomy 15:12, 13, 18 (Sarna 1973:145-146).

Except for the allusion in Jeremiah 34:8-22, to the debt release law in Deuteronomy 15:12-18, several other allusions to the Book of Deuteronomy are attested in the pericope. The threat of Israel becoming "a horror to all the kingdoms of the earth" (34:17) has its source in Deuteronomy 28:25. Jeremiah 34:18 was inspired by Deuteronomy 27:26, while the dire punishment of Jeremiah 34:20 that the carcasses of those who transgressed the covenant would "become food for all the birds of the sky and the beasts of the earth" has been drawn directly from Deuteronomy 28:26 (Sarna 1973:145). These allusions testify to the fact that an earlier form of the Book of Deuteronomy belonged to the recognised literary canon of the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22.

He would in all likelihood expect that the text's audience would succeed in identifying the allusion (Edenburg 2010:144).

The relationship between Deuteronomy and Jeremiah is by no means unidirectional. The Book of Jeremiah exerted influence on later additions to Deuteronomy (Holladay 1989:53-63; Mastnjak 2016:216-226). The laws in Deuteronomy 15:1-18 do, however, belong to the core of the Book of Deuteronomy, chapters 12-26. This does not necessarily imply that these chapters are free of later additions. Otto (2015:341), for instance, attributes 15:4-6, 11 to a "nachexilische Fortschreibung" by post-Deuteronomistic and post-Priestly redactors.

3. THE EFFECT OF THE ALLUSION TO DEUTERONOMY 15 ON JEREMIAH 34:8-22

Jeremiah 34:9 obviously presupposes Deuteronomy 15:12, as is evident from the use of the terms עברי and עבריה. The introductory phrase מקץ שבע שנים in Jeremiah 34:14 functions as a marker. A marker is an identifiable element or pattern in one text belonging to another text, which enables the reader to identify the source text (Sommer 1998:11; Edenburg 2010:144). Once the two texts have been linked by the marker's evocation of the marked, the reader will recall other signs within each text that will affect the interpretation of the alluding text (Sommer 1998:12; Mastnjak 2016:14).

The disparity in Jeremiah 34:14 between the opening clause מקץ שבע שנים and the instruction ועבדך שש שנים ובשנה השביעת תשלחנ has caused a great deal of discussion. The Septuagint harmonised the clauses by correcting the initial "seven" to "six". The conventional solution to the apparent temporal problem is to suggest that מקץ means "at the beginning of" or "at the time of", rather than "at the end of". Mastnjak (2016:150-152), however, proposed that the text attempts to combine the calendrically fixed seven-year cycle of the debt release law with that of the slave release law that mandates six years of labour followed by a release at the beginning of the seventh. Since both cycles are to be followed, the system will work in favour of the slave, who will be released either at the end of the calendrically fixed seven-year cycle of the debt release law or after six years of labour, whichever came first. Deuteronomy 15 does not combine these systems as Jeremiah 34:14 does, but the juxtaposition of the debt release law with that of the slave release law could imply such a combination. A more palpable solution is that the clause מקץ שבע שנים should be taken as a jump from the introductory Deuteronomy 15:1, which refers to the release of debts at the end of every seventh year, to 15:12. The text signifies that the release of debt slaves in 15:12 should be interpreted in terms of the communal debt remission in 15:1 (Allen 2008:387).

As noted earlier, the narrative that introduces the judgement oracle in Jeremiah 34:8-22 agrees with Deuteronomy 15:12, by referring to the debt slaves with the terms 'עברי and עבריה. In Exodus, the term עברי indicates membership of a subgroup with low social status (Nelson 2002:97). In Deuteronomy 15, the term עברי is connected with the term "-אחיך, "your brother". It is noteworthy that -אחיך is added in verse 12 at the expense of stylistic smoothness (Houston 2006:186). In verse 3, אחיך is contrasted with נכרי "foreigner", implying that אח refers to a fellow Israelite (Chirichigno 1993:278). In the expression אחיך העברי או העבריה, the definite העברי and העבריה are appositions to the subject אחיך (Tsai 2014:45). Through the pairing of אח with עבריה / עברי in Deuteronomy 15:1-18, the term אח is pushed to its widest possible association (Hamilton 1992:40). It is, nonetheless, restricted to fellow Israelites. This nationalist attitude, present in Deuteronomy 15:1-18 (Scheffler 2005:103), is also attested in Jeremiah 34:8-22. The author is exclusively concerned with the Judean debt slaves.

The term אח, which is not found in the slave release law in Exodus 21:2-6, occurs six times in the debt release and the slave release laws in Deuteronomy 15:1-18 (vv. 2, 3, 7, 9, 11, 12). Remarkably, the second person singular suffix occurs in the majority of these cases (vv. 2, 3, 7, 9, 11, 12). While verse 3 uses the term אח to differentiate the Israelite from the foreigner, the second person singular suffix emphasises kinship in the other cases (Houston 2006:181). In verses 7 and 9, the term אח occurs in apposition to the term אביון, "poor". The use of אח in verse 12 clarifies that the slave, who had to be released, should also be identified with the poor (Hamilton 1992:38). Although the Masoretic reading of אח in Jeremiah 34:17 is not supported by the LXX, verses 9 and 14 refer to the debt slaves as "brothers", in these cases applying the third person singular suffix. This is due to the literary context. Verse 9 forms part of the introduction to the oracle proper. Verse 14 is presented as a quotation of a command directed at the ancestors of the people. Jeremiah 34:8-22 clearly echoes the "brother ethics" present in Deuteronomy 15:1-18.

Deuteronomy 15:15 establishes an emotional parallel between the situation of the whole people of God as slaves in Egypt to that of the debt slaves (Hamilton 1992:24). Both slave and owner shared the experience of having been עברי (Hamilton 1992; Tsai 2014:44-45). The releasing of the slave was, in effect, a recreation in miniature of the divine act of redemption from Egyptian servitude (Hamilton 1992:39-40). The brother ethics was a consequence of YHWH's redemption from the land of slavery (Braulik 1988:320).

Strikingly, Jeremiah 34:13 refers to Egypt as the עבדים בית, "the land of slavery", a phrase that frequently occurs in Deuteronomy (5:6; 6:12; 7:8; 8:14; 13:6, 11). Since this is the sole occurrence of this phrase in the Book of Jeremiah (Holladay 1989:241), the author evidently also wanted to evoke the memories of Israel's history in Egypt.

Deuteronomy 15:16-17 states that only the desire of the slave could negate the intention to free him (Hamilton 1992:21). In Jeremiah 34:16, the phrase שלחתם חפשים לנפשם "released to their desire", testifies to the fact that the release enacted by Zedekiah complied with this requirement. However, by forcing the manumitted slaves back into slavery, as is implied by the verb כבש (Jer. 34:11), the slave owners acted contrary to the requirements of the slave release law in Deuteronomy 15. The slave owners would, therefore, suffer the punishment announced in Deuteronomy 28:25: They would become "a horror to all the kingdoms of the earth" (Jer. 34:17).

In Jeremiah 34:14-15, the covenant concluded by king Zedekiah and the people in Jerusalem to proclaim freedom for the Judean slaves is likened to the covenant YHWH made with the forefathers at the time of the Exodus. In a recent study, Tsai (2014:66) emphasised that Deuteronomy 15:12-18 should be perceived against the background of YHWH's covenant with Israel. Those who had experienced YHWH's redemption and selflessness should treat others with equality. By referring to the covenant YHWH made with the forefathers at the time of the Exodus, the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 stresses that the slave owners in Zedekiah's time should have treated their Judean slaves differently. Curiously, in verse 18, the Masoretic rendering העגל אשר כרתו לשנים ועברו בין בתריו "the calf which they cut in two and then walked between its pieces", has apparently been shaped by the covenant incident in Genesis 15, although, in that instance, it was YHWH who passed symbolically through the pieces. The Old Greek variant seems to have the golden bull incident in Exodus 32 in mind (Stulman 1986:103).

In Deuteronomy 15:1-18, the term κη does not have a distinctive gender tone. Verse 12 explicitly includes women under the category of "brother" (Vogt 2008:40). Likewise, the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 is also concerned with the female debt slaves.

Jeremiah 34:8-22 does not merely reflect the influence of Deuteronomy 15:1-18. Fischer (2011:262-265) believes that the connections between these texts are so extensive that one should reckon with a deliberate literary undertaking. Mastnjak (2016:227) observed that the Deuteronomic text functions as an authoritative text for the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22. Mastnjak (2016:14), however, acknowledged that, in the case of an allusion, the interpretation of the alluding text will be affected by the recollection of signs in the source text. To use the phraseology employed by Sommer (1998:25), the viewpoint of Jeremiah 34:8-22 as a whole depends on that of Deuteronomy 15:1-18. Through the allusion to Deuteronomy 15:1, 12, the humane character of Deuteronomy 15:1-18 is transferred to Jeremiah 34:8-22. The slave owners should have treated the manumitted slaves as "brothers".

4. THE AUTHOR OF JEREMIAH 34:8-22: A VOICE FOR THE MARGINALISED

The author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 uses a wordplay on the term דרור with a devastating effect. Since the slave owners have not obeyed YHWH in דרור קרוא , "proclaiming liberty", he would "proclaim liberty" to them - to sword, pestilence and famine. They would fall by the sword, pestilence and famine (Holladay 1989:242). The conduct of the slave owners with regard to their debt slaves thus provided a justification of YHWH's action in bringing about the fall of Jerusalem in 587 B.C.E. There is no evidence that the release, enacted under the auspices of Zedekiah, was based on the slave release law in Deuteronomy 15:12 (Chirichigno 1993:285). Zedekiah's action can be compared with the declaration of the mêsarum edicts, royal proclamations that sought to release citizens from various forms of debt (Chirichigno 1993:85). The readiness to re-enslave the freed slaves is an indication that the slave owners did not view the covenant organised by Zedekiah as any specific divine commandment (Chavel 1997:73). The author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 does not make any connection with the sabbatical or jubilee year (Carroll 1986:648). He transformed the proclamation of manumission into an infringement of the Deuteronomic law (Thiel 1981:43). He uses the allusion in verse 14 to the debt release and the slave release laws in Deuteronomy 15:1-18 in order to bring the brother ethics of Deuteronomy to bear on the state of affairs. In this manner, he demonstrates a real concern for the Judean debt slaves.

Messenger formulae, attributing the criticism of the slave owners to YHWH, occur repeatedly in Jeremiah 34:12-22 (vv. 13, 17a, 17b, 22). The reference in verse 13 to the covenant concluded with the ancestors to release the slaves is introduced by the emphatic pronoun "I". YHWH himself made a covenant with the forefathers, which implied that a debt slave should be set free after six years of service. The author of Jeremiah 34:8-22's concern for the Judean debt slaves is derived from YHWH's stance.

Jeremiah 34:8-22 does not mention the causes of the debt slavery in Zedekiah's time. When Necho demanded tribute from Jehoiakim, the latter raised it from the people (2 Kgs 23:35). Nobles, landowners and other people of means charged excessive interest on loans (Lundbom 2004:559). When a debtor could not pay an overdue loan, his dependents could have been seized (Chirichigno 1993:269). In Jeremiah 34:14, the verb ימכר could be translated as a passive or a reflexive (Nelson 2002:262). Because of debt, the debt slaves were either sold or sold themselves. The former in all likelihood happened (contra Holladay 1989:240).

Other texts in the Book of Jeremiah, namely 7:5-7 and 22:1-5, also focus on protecting socially marginalised groups (Maier 2008:31). The alien, the fatherless or the widow should not be oppressed, and the blood of the innocent should not be shed. Like 34:8-22, these texts display the so-called sermonic prose, which is frequently attributed to either a Deuteronomistic redaction (Hyatt 1984:254-260) or multiple Deuteronomistic redactions (Römer 2000:418-419; Albertz 2003:312). It has been suggested that it is likely that the Deuteronomistic redactors are to be founded among the Shaphainide officials (Lohfink 1995:360; Albertz 2003:326). One of these officials, the author of 34:8-22, is evidently concerned with a specific marginalised group, the debt slaves.

5. CONCLUSION

Although Jeremiah 34:8-22 uses the re-enslavement of manumitted slaves as a precedent that explained the fall of Jerusalem in 587 B.C.E, the allusion in 34:12 to the laws in Deuteronomy 15:1, 12 transfers the "humanitarian" concerns of these laws, to the pericope. The author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 not only recognised the debt release and the slave release laws in Deuteronomy 15:1-18 as divine commands, but also shared their "humanitarian" concerns. The debt slaves should be treated as brothers and not as mere objects. He thus became a voice for these marginalised Judeans.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albertz, R. 2003. Israel in exile. The history and literature of the sixth century B.C.E. Atlanta, GA: Society for Biblical Literature. [ Links ]

Allen, Lu. 2008. Jeremiah. A commentary. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox. OTL. [ Links ]

Braulik, G. 1988. Das Deuteronomium und die Menschenrechten. In: G. Braulik, Studien zur Theologie des Deuteronomiums (Stuttgart: Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk), pp. 301-323. [ Links ]

Carroll, R.P. 1986. Jeremiah. A commentary. London: SCM Press. OTL. [ Links ]

Chavel, S. 1997. "Let my people go!" Emancipation, revelation and scribal activity in Jeremiah 34:8-14. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 76:71-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/030908929702207605 [ Links ]

Chirichigno, G.C. 1993. Debt-slavery in Israel and the Ancient Near East. Sheffield: JSOT Press. JSOTSS 141. [ Links ]

Doorley, W.J. 1994. Obsession with justice. The story of the deuteronomists. New York: Paulist Press. [ Links ]

Edenburg, C. 2010. Intertextuality, literary competence and the question of readership: Some preliminary observations. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 32:131148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309089210387228 [ Links ]

Fischer, G. 2011. Der Einfluss des Deuteronomiums auf das Jeremiabuch. In: G. Fischer, D. Markl & S. Paganini (eds.), Deuteronomium - Tora für eine neue Generation (Wiesbaden: Harrossowitz BZAR 17.), pp. 247-269. [ Links ]

Hamilton, J.M. 1992. Social justice and Deuteronomy. The case of Deuteronomy 15. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature. [ Links ]

Holladay, W.L. 1989. Jeremiah 2. A commentary on the book of the prophet Jeremiah. Chapters 26-52. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. Hermeneia. [ Links ]

Houston, W.J. 2006. Contending for justice. Ideologies and theologies of social justice in the Old Testament. London: T. & T. Clark. Library for Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 428. [ Links ]

Hyatt, J.P. 1984. The deuteronomic edition of Jeremiah. In: L.G. Perdue & B.W. Kovacs (eds.), A prophet to the nations. Essays in Jeremiah studies (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns), pp. 247-267. [ Links ]

Lemche, N.P. 1976. The manumission of slaves - the fallow year - the sabbatical year - the yobel year. VT 26:38-59. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853376X00196 [ Links ]

Leuchter, Μ. 2008. The manumission laws in Leviticus and Deuteronomy: The Jeremiah connection. Journal of Biblical Literature 127:635-653. https://doi.org/10.2307/25610147 [ Links ]

Lohfink, N. 1995. Theology and the Pentateuch: Themes of the priestly narrative and Deuteronomy. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Lundbom, U.R. 2004. Jeremiah 21-36. A new translation with introduction and commentary. New York: Doubleday. The Anchor Bible. [ Links ]

Maier, CM. 2008. Jeremiah as teacher of Torah. Interpretation 62:22-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/002096430806200103 [ Links ]

Mastnjak, N. 2016. Deuteronomy and the emergence of textual authority in Jeremiah. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. FAT 2/87. https://doi.org/10.1628/978-3-16-154402-6 [ Links ]

Nelson, R.D. 2002. Deuteronomy. A commentary. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox. OTL. [ Links ]

Otto, E. 1999. Das Deuteronomium. Politische Theologie und Rechtsreform in Juda und Assyrien. Berlin: De Gruyter. BZAW 284. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110802191 [ Links ]

Otto, E. 2015. The integration of the post-exilic Book of Deuteronomy into the post-priestly Pentateuch. In: F. Guintoli & K. Schmid (eds.), The post-exilic Pentateuch. New perspectives on its redactional development and theological profiles (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck FAT), pp. 331-341. [ Links ]

Römer, Τ. 2000. Is there a deuteronomistic redaction of the book of Jeremiah? In: A. de Pury, T. Römer & J.-D. Macchi (eds.), Israel contructs its history. Deuteronomistic historiography in recent research (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press JSOTSS 306.), pp. 399-421. [ Links ]

Sarna, N. 1973. Zedekiah's emancipation of slaves and the sabbatical year. In: H.A. (jr). Hoffner (ed.), Orient and occident. Essays presented to Cyrus H. Gordon on the occassion of his sixty-fifth birthday (Kevelaer: Verlag Butzen & Bercher AOAT 22), pp. 143-149. [ Links ]

Scheffler, Ε. 2005. Deuteronomy 15:1-18 and poverty in South Africa. In: E. Otto & J. le Roux (eds.), A critical study of the Pentateuch. An encouter between Europe and Africa (Münster: Lit Verlag Altes Testament und Moderne 20.), pp. 97-115. [ Links ]

Sommer, B.D. 1998. A prophet reads Scripture. Allusion in Isaiah 40-66. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Stulman, L. 1986. The prose sermons of the book of Jeremiah. A redescription of the correspondences with deuteronomistic literature in the light of recent text-critical research. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press. SBL Dissertation Series 83. [ Links ]

Terblanche, M.D. 2016. Jeremiah 34:8-22 - A call for the enactment of distributive justice. Acta Theologica 36(2):148-161. [ Links ]

Thiel, W. 1981. Die deuteronomistische Redaktion von Jeremia 26-45. Mit einer Gesamtbeurteilung der deuteronomistische Redaktion des Buches Jeremia. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag. WMANT 52. [ Links ]

Tsai, D.Y. 2014. Human rights in Deuteronomy with special focus on slave laws. Berlin: De Gruyter. BZAW 464. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110364422 [ Links ]

Vogt, P.T. 2008. Social justice and the vision of Deuteronomy. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 51(1):35-44. [ Links ]

Weinfeld, Μ. 1972. Deuteronomy and the deuteronomic school. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]