Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.39 suppl.27 Bloemfontein 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup27.1

ARTICLES

Unheard/ Heard Voices In Exodus 1-17 And Some Thoughts On Poverty In South Africa

J.S. van der Walt

Dr. J.S. van der Walt Research Fellow, Department of Old and New Testament Studies, University of the Free State, South Africa. E-mail: ideo@caw.org.za. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5152-3029

ABSTRACT

When someone cries, it usually signals that something is wrong or that there has been some kind of unsettling experience. One can cry because of emotional pain, physical pain and even anger. Crying is not always heard though. A cry of silence may not be noticeable, but this does not mean that there is less pain or emotion. In Exodus 1-17, the theme of crying is presented from different angles. This article focuses on different aspects of crying in the Exodus tradition, which starts with a silent cry, and on the so-called absence of YHWH, which, in fact, points to an undoubtedly absent presence. In conclusion, with insights drawn from the narrative text, the article offers some thoughts on the theme of poverty in South Africa, as unheard voices in this regard should also be heard, with the church being the most likely agent to deliver this message.

Keywords: Exodus 1-17, Cry motif, Murmuring motif

Trefwoorde: Eksodus 1-14, Huilmotief, Klaagmotief

1. INTRODUCTION

The aim of this article is to focus on the "silent voices"1 in Exodus 1-17, within a tripolar2 framework (West 2018:43). First, the article explains the different characteristics of the cry motive in the Exodus tradition, which starts with a silent cry.3 Secondly, the article offers theological observations denoting crying and murmuring in Exodus 1-17. In conclusion, with insights drawn from the narrative text, some thoughts on the theme of crying in Exodus 1-17 will be used as an analogy to poverty in South Africa, with final remarks on the question: "Do the unheard voices in the Exodus narrative have a message for the church4 in South Africa?" This article does not intend to give a final answer to this hypothetical question, but rather to stimulate debate inspired by the theme of the conference at which this article was delivered.

2. DIFFERENT CHARACTERISTICS OF THE CRY MOTIVE IN EXODUS 1-17

Some scholars argue that the Book of Exodus should not be read as an independent piece, as it forms part of a larger whole, also known as the Pentateuch (Birch et al. 1999:100).5 Others argue that the first reader/s of the Exodus story in its final form belonged to an oppressed society during the Babylonian exile, in approximately 586/587 B.C. (Kratz 2008:471; Lemmelijn 2007:412; Van der Walt 2014:144).6 The first reader/s, being in an uncomfortable position of oppression, might have sensed the "absence" or even "passiveness" of YHWH in Exodus 1 to 2 (Lemmelijn 2007:412). Just when hope surfaced on the horizon with the birth of a baby boy (Moses), who had also been saved from the Nile, more tension within the narrative aroused when the once saved baby fled from Egypt during his adulthood.

Exodus 1-2 should not be read in isolation, as it forms part of a bigger plot (House 1998:90). Thus, during the first stage of the Exodus narrative, there is tension between hope and disappointment. Moses was saved as a baby (hope), but the "hero" to be eventually fled from Egypt (disappointment). The tension builds up to a climax at the end of Exodus 2, as the narrator mentions that YHWH heard the outcry of his people and remembered his covenant with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (Ex. 2:23-25). Brueggemann (2008:27) puts it this way:

[I]t was only the cry of the silenced that evoked an active divine remembering ... It is this exchange of 'cry-hear' that evokes the theophany in chapter 3.

In other words, without the cry, there would probably not have been an exodus. Within the Exodus narrative, the cry motif is, therefore, crucial.

An important suggestion to bear in mind is that, although the cry7 motif is a strong motif within the exodus tradition, the focus in the narrative is not on Israel's complaints, but rather on YHWH as the One who hears and remembers: "The fact that God hears means that God will act" (House 1998:91). I shall now examine different characteristics of words in Exodus 1-17 that denote a cry motif.

2.1 Exodus 2:6 [ בָּכהָ (bakah)]

Bakah (to weep)

is the natural and spontaneous expression of strong emotion [and it] is especially prominent in the narrative literature, although it also occurs frequently in the poetic and prophetic books (TWOT8 243).

In the context of Exodus 2:6, בָּכהָ is used to describe a baby "crying in distress ... thus the baby Moses began to cry in the Pharaoh's daughter's presence [Ex. 2:6]" (TWOT 243).

Fretheim (1991:7) suggests that there is a mirroring effect of wordplay in the structural outline of Exodus 1-15. If he is correct, Moses' crying and Pharaoh's daughter's compassion for him mirror the outcry of the people and YHWH hearing them (Ex. 2:23). In a sense, this mirroring effect implies the notion of a silent voice. In the words of Childs (1965:116): "The role of the princess climaxes the theme which runs throughout the story." The real action still lies in the future and these are only preliminary events. In other words, crying leads to compassion. Even though it appears that the crying is not being heard, as in the outcry of the people, compassion is on its way. Ironically, the Pharaoh's daughter's compassion points to hope. Later in the narrative, YHWH brings hope when he delivers his people through his agent, Moses.

2.2 Exodus 2:23 [ זעַָק (zaaq)]

In the Old Testament, the word זעַָק occurs for the first time in Exodus 2:23. This word indicates "crying out for aid in time of emergency, especially for divine help" (Strong 2001:445). In Exodus 2:25, the narrator mentions that "God looked on the Israelites and was concerned about them". The word suggests that "God looked on the Israelites and knew about their agony" (Waltke 2007:357). The narrator also creates the anticipation of "an exclusive relationship in which God pledges to treat the elect as his 'treasured possession'" (Waltke 2007:357). By creating this anticipation, the implied reader could sense that YHWH will deliver His "treasured possession".

2.3 Exodus 3:7, 9 [ צעְקָָה (tseaqah)]

In the Arabic language, the original meaning of tseaqah signals a sound such as thunder, thus stressing the cry of the people as "to call out for help under great distress or to utter an exclamation in great excitement" or "anguish" (TWOT 1947a). Kaiser points to the fact that, as is the case in Exodus 2:23, the cry (silent voice) is not unnoticed: YHWH "sees", YHWH "hears", and YHWH is "concerned" about his people (Kaiser Jr. 1990:316; BDB 1947a9). Exodus 3:9 repeats the fact that YHWH has heard and seen "Israel's present need" and offers the solution, namely "the formal commissioning of Moses as God's emissary to lead Israel out of Egypt" (Kaiser Jr. 1990:316).

2.4 Exodus 5:8 [ צעַָק (tsaaq)]

Tsaaq is a synonym of zaaq [Ex. 2:23] (Strong 2001:445, 770).10 In Exodus 2 and 3, YHWH heard the cry of the people. In Exodus 5, Pharaoh also hears the cry (via Moses); the difference, however, is that Pharaoh's solution to the cry is to let the people suffer more. To Pharaoh, so it seems, Israel acts defiantly; therefore, their voice is definitely silent to him! The tension in the narrative thus intensifies, as there is no quick solution to the people's cries. In fact, Fretheim (1991:83) states that the cries are suddenly "deafening silent" in Exodus 5. Everyone (Moses, Pharaoh, the slave drivers, Israelite foremen, YHWH) has a say, except the people, those with the unheard voices! The author subtly hides the cry motif in Exodus 5, providing "a picture of the depths of Israel's situation and the ruthlessness of oppressive systems" (Fretheim 1991:83). The building up of tension, however, helps set the stage for YHWH's redemptive plan further on in the narrative.

2.5 Exodus 14:10, 15 [ צעַָק (tsaaq)]

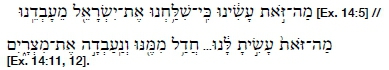

The Israelites' thunderous cry (TWOT 1947a) is heard for the last time in the Exodus narrative when their "cry is channeled through Moses, and it takes the form of a complaint" (Fretheim 1991:155). At this stage of the narrative, the cry motif is starting to transform into a murmuring motif. Hence, Exodus 14:10 is the "first of many such murmurings", which Israel will voice during the wilderness sojourn (Fretheim 1991:156). Ford (2006:177) mentions the obvious parallelism between Exodus 14:5 and 14:11, 12:

It is noticeable that Israel's focus is on Pharaoh whom they choose to serve. It is as if they reckon that YHWH does not hear their cries. They (Israel) do not reckon with YHWH's plan (Ford 2006:177; Childs 2004:226). In response to this, Moses challenges Israel to respond to YHWH's plan (Childs 2004:226). His challenge points to the opposite of crying, namely silence (ח רַָשׁ [charash]): "The LORD will fight for you while you keep silent" (Ex. 14:14 NAS). The author outlines the fact that nothing which the people would say can "add to what God is effecting on their behalf" (Fretheim 1991:157). For the first time in the narrative, a silent voice is presented as a positive notion. It is all right to keep silent, for YHWH will act on Israel's behalf.

2.6 Exodus 15:24; 16:2; 17:3 [לוּן (lun)]; 16:7, 8, 9, 12[ תְּלנֻּהָ(telunnah)]

The word לוּ (lun) occurs for the first time with the meaning of murmuring in Exodus 15:24.11 It is "confined to the wilderness wanderings in Exodus and Numbers", with the exception of Joshua 9:18 and Psalm 59:16 (Childs 2004:266). לוּ (lun) "denotes a grumbling and muttered complaint" (Childs 2004:266).

In TWOT 1097, תְּלנֻּהָ is described as "verbal assaults", usually against Moses and Aaron (Ex. 16:2; Num. 14:2):

[occasionally, Moses is singled out (Ex. 15:24; Ex. 17:3; Num. 14:36) or Aaron (Num 16:11); at other times the Lord himself is the object of their abuse (Ex. 16:7-8; Num 14:27, 29).

In the final analysis, however, Israel's "murmuring was always against God who commissioned the leaders of the people" (TWOT 1097a). A silent voice can, therefore, also have a downside. In a negative way, it means that, through their murmurings, Israel actually testifies that they do not trust Moses, or YHWH.

3. BRIEF THEOLOGICAL OBSERVATIONS DENOTING CRYING AND MURMURING IN EXODUS 1-17

A broad analysis of crying and murmuring indicates that a silent voice is noted, especially during the first part of the Exodus story. The silent voice then gradually turns into a heard, vocal cry, which eventually transforms to an unsatisfying murmuring.

Of note is the set of traditional "stereotyped language of the complaints" which denotes "close similarity in both form and content" within Israel's protests (Childs 2004:257). Childs (2004:258) has detected "two distinct patterns" regarding the murmuring motif within the wilderness stories. The first pattern is found in Exodus 15:22f.; 17:1f. and Numbers 20:2. The pattern starts with a need (Ex. 15:22, 23; 17:1), followed by a complaint (Ex. 15:24; 17:2), which is then followed by "an intercession on the part of Moses" (Ex. 15:25; 17:4) issuing the need. It is then met by YHWH's "miraculous intervention" (Ex. 15:25; 17:6f.).

The second pattern falls outside the field of investigation of this study. It can be briefly mentioned that this pattern has striking similarities with the first pattern, with two major differences being that Israel's initial complaint (Num. 11:1; 17:6; 21:5) is followed by God's anger and punishment (Num. 11:1; 17:10; 21:6). Moses' intercession is then followed by "a reprieve of the punishment" (Num. 11:2; 17:50; 21:9) (Childs 2004:258). The first pattern thus focuses on Israel's genuine need in the wilderness, with YHWH acting "with the miraculous gift of food and water" to sustain them in the harsh environment of the wilderness, while the second pattern focuses on Israel's "disobedience in the desert and the subsequent punishment and eventual forgiveness which their unbelief called forth" (Childs 2004:259).

A further observation is that the wilderness stories use "the elements of rebellion" (murmurings) as an "overarching category by which to interpret the exile and other disasters" (Childs 2004:263). For the first reader/s, the message would thus be clear: YHWH will meet the need and sustain those with the unheard voices, because he even hears "silence".

4. THE UNHEARD VOICES OF THE POOR INSOUTH AFRICA

If one considers all the unheard voices of postmodern society, the images are gloomy and miserable. They are the unheard voices of poverty, of those who lack access to food and medical care; child and spouse abuse, various forms of political oppression, victimisation, and so forth.12

Stats SA (2017) released data indicating that "poverty is on the rise in South Africa". These web-based statistics point to the fact that "more than half of South Africans were poor in 2015, with the poverty headcount increasing to 55.5% from a serious low of 53.2% in 2011". Children under the age of 17 were affected the most. This fact serves as an enormous threat with regard to healthy childhood development. According to the latest Living Conditions Survey data, during 2015, this has been the unfortunate reality for over 13 million children living in South Africa. These statistics are not confined to a specific portion (rural or urban) of, or province in South Africa. Indeed

all states [sic, provinces] in the Southern African subregion face the challenges of rural and urban poverty, limited water or access to water resources, food insecurity, and other development challenges (Flottum & Gjerstad 2013:12).

The question is whether something drastic could be done to save the gloomy situation? According to a survey done in 2017 by Jayson Coomer, only 13% of the South African population of 56 million people was paying income tax - "with the other 87% not contributing anything (though still contributing to VAT)." It does not take rocket science to see that any government will struggle to meet the need of the poor with statistics such as these. Flottum & Gjerstad (2013:29) further note that the poor play a passive role in their dependence on the "benevolence" of a government that attributes the role of "hero" to itself.

Another gloomy document is that of the World Bank, published in March 2018. According to this document, which listed 149 countries, "South Africa is the most unequal country in the world". Times Live (4 April 2018) gives a summary:

The report analyzed South Africa's post-apartheid progress, focusing on the period between 2006 and 2015. The report found the top 1% of South Africans own 70.9% of the country's wealth while the bottom 60% only controls 7% of the country's assets. Neighbours Namibia and Botswana were second and third. Zambia, Central African Republic, Lesotho, Swaziland, Brazil, Colombia and Panama completed the top 10. More than half of South Africans (55.5%) or 30-million people live below the national poverty line of R992 per month. This number increased since 2011. The groups worst affected by poverty are black South Africans, the unemployed, the less educated, female-headed households, large families and children. The official unemployment rate was 27.7% in the third quarter of 2017 while youth unemployment was 38.6%.

In a research paper by the South African Institute of Race Relations, published in March 2011, Holborn and Eddy (2011:2) highlight the following statistics with regard to the younger generation in South Africa, also known to some as the "lost generation":

• Only 35% of South African children are raised by both biological parents.

• Between 1996 and 2009, the percentage of children without fathers escalated from 46% to 52%.

• There are an estimated 1.4 million orphans, due to HIV.

• Only 34% of South African children live in a home where at least one parent has permanent employment.

Poverty inevitably leads to other social problems such as crime, gangsterism, health issues, among others, which could not be addressed in this article. The question would still be: What about the unheard voices of the poor? The above statistics point to immense imbalances that spell only disaster for future generations. In 2014, a delegate at an UN conference in Genève made this remarkable comment:

The question is not, what kind of world we leave behind for our children, but rather, what kind of children do we raise for the future? (Hanekom 2015:121).

How do you raise a hungry child?

5. UNHEARD VOICES IN THE EXODUS NARRATIVE, A MESSAGE FOR THE CHURCH IN SOUTH AFRICA?

Returning to the Exodus narrative, different angles to the cry motif have been pointed out. One of the theological outcomes of these cries, in one sentence, could be to say that the unheard voices in Exodus were, in fact, heard:

The Lord said, "I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about their suffering. So I have come down to rescue them from the hand of the Egyptians and to bring them up out of that land into a good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey..." (Ex. 3:7-8 NIV).

These words were meant to comfort and encourage the first readers not to forget YHWH. He has not forgotten them and He heard their cries. These narratives were carried over from one generation to another: To comfort and to encourage!

Even the early church benefitted from the Old Testament stories as a form of encouragement. They were reminded, through some of Jesus' wondrous acts, that YHWH does care and does hear the silent cries of the oppressed. It is interesting to note that many of the wonders performed by Jesus are similar to the divine wonders in the Old Testament,13 thus helping the early church to remember that the same God who heard in the Old Testament is still hearing. Beyond the early church, every new generation also had their own stories to tell, with poverty always being an issue. Poverty is nothing new, except that the world's population is growing, thus increasing the challenge to overcome poverty.

The short answer to whether the (unheard voices in the) Exodus narrative could have a message for poverty-stricken people in South Africa would be, yes, indeed. Albeit the next question would be: How does YHWH react to the silent voices in this post-modern South Africa? As mentioned earlier, some scholars argue that the editors of the Exodus story in its final form had in mind a (first) reader/s who were also likely to be caught up in oppression. They were to be reminded that even unheard voices are heard by YHWH and that he does not distance himself from their cries.

It should also be mentioned that YHWH always made use of partners (Brueggemann 1997:413-528). In the Exodus story, YHWH chose a deliverer, Moses, to deliver his people from Egypt. Later in history, he made use of prophets to remind his people that he is their provider and sustainer.

In the New Testament, Jesus chose disciples to establish his church as his partner in order to make a difference in the world. Currently, the church must remind those in poverty that YHWH still hears, also the unheard voices, by telling the stories of redemption as in Exodus 1-17.

Section 4 above pointed to the increase in poverty in South Africa and the government's inability to cope with growing social demands. The church of the day should, therefore, take this opportunity to partner with the One who also hears the silent cries in this given time. The early church did so in a time when the government of the day, the Roman Empire, did not hear the silent cries of the widows and the orphans. The early church played an active role in helping the poor (Acts 6:2; James 1:27; 2:14-17).

In conclusion, it could thus be stated that Exodus 1-17 reminds us that YHWH heard and responded to silent voices. The question is: Do we?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Birch, B.C., Brueggemann, W. Fretheim, T.E. & Petersen, D.L. 1999. A Theological Introduction to the Old Testament. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 1997. Theology of the Old Testament. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W.2008. Old Testament theology. An introduction. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Bushell, M.S., Tan, M.D. & Weaver G.L. 1992-2008. BibleWorks 8. Electronic edition. BibleWorks, LLC. [ Links ]

Childs, B.S. 2004. The Book of Exodus. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Childs, B.S. 1965. The birth of Moses. Journal of Biblical Literature 84(2):109-122. https://doi.org/10.2307/3264132 [ Links ]

CüOMER, J. 2017. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://businesstech.co.za/news/finance/207631/this-is-who-is-paying-south-africas-tax/ [5 April 2018]. [ Links ]

Flottum, K. & Gjerstad, O. 2013. The role of social justice and poverty in South Africa's national climate change response white paper. South African Journal on Human Rights 29(1):61-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/19962126.2013.11865066 [ Links ]

Ford, W.A. 2006. God, Pharaoh, and Moses. Explaining the Lord's actions in the Exodus plagues narrative. Milton Keynes: Paternoster. Biblical Monographs. [ Links ]

Fretheim, T.E. 1991. Exodus. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Hanekom, B. 2015. Wat is die verskil tussen kerke wat groei en kerke wat sterf? Kaapstad: MCM Boeke. [ Links ]

Harris, L., Archer, G.L. Jr. & Waltke, B.K. 1980. TWOT - The theological wordbook of the Old Testament. Electronic edition. Chicago, ILL: Moody Press. [ Links ]

Holborn, L. & Eddy, G. 2011. First steps to healing the South African family. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://irr.org.za/reports/occasional-reports/files/first-steps-to-healing-the-south-african-family-final-report-mar-2011.pdf [5 April 2018]. [ Links ]

House, P.R. 1998. Old Testament theology. Westmont, ILL: Intervarsity Press. [ Links ]

Kaiser, W.C. Jr. 1990. Exodus. In: A.C. Gaebelein (ed.), The Expositor's Bible Commentary. Volume 2 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House), p. 316. [ Links ]

Kratz, R.G 2008. The composition of the Bible. In Rogerson, J.W. (Ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford: University Press. [ Links ]

Lemmelijn, B. 2007. Not Fact, yet true Historicity versus Theology in the "Plague Narrative". Exodus 7-11. OTE 20(2):395-417. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa 2017. Poverty trends in South Africa. An examination of absolute poverty between 2006 and 2015. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=10334 [4 April 2018]. [ Links ]

Strong, J. 2001. The new Strong's expanded dictionary of Bible words. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers. [ Links ]

Times Live 2018. Overcoming poverty and inequality in South Africa. An assessment of drivers, constraints and opportunities. [Online.]. Retrieved from https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2018-04-04-poverty-shows-how-aparheid-legacy-endures-in-south-africa/ [4 April 2018]. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, J.S. 2014. A biblical-theological investigation of the phenomenon of wonders surrounding Moses, Elijah and Jesus. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

Waltke, B.C. 2007. An Old Testament theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House. [ Links ]

West, G.O. 2018. Accountable African biblical scholarship: Post-colonial and tri-polar. Biblical Interpretation Series 161:241-270. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004363540_012 [ Links ]

1 In my opinion, a silent voice within the context of the biblical text is to be understood as someone crying or murmuring, due to some kind of oppression. In some instances, the reader could get the impression that the person or persons crying or murmuring are not being heard, thus creating a feeling of hopelessness.

2 West (2018:43) suggests three intersecting poles in the tripolar analysis: the African context, the biblical text, and the ideo-theological forms of dialogue between the African context and the biblical text. For the purpose of this article, the (South) African context will be discussed at the end.

3 A silent cry is to be understood as an emotion of despair or utter helplessness, as in the case of Israel being oppressed by the Pharaoh. They had no one to turn to, no one who could listen to them and save them from their sufferings.

4 Being in full-time ministry and experiencing the effects of poverty in my own backyard, I do believe that inspirational stories of the past, such as the Exodus story in the Bible, should have a positive message for those people struggling with poverty in our own context. Surely, the church has a role to play in bringing the stories to the people.

5 I made use of the canon of Scriptures (Old Testament) in its final form. Argumentation with regard to historical contex is offered in terms of a narratological approach, bearing in mind to whom the story in its final form could have been addressed (the so-called first reader).

6 We could argue for other time frames with regard to the final editing of the Exodus narrative, but the scope of this article does not permit a more detailed discussion of this notion. Many scholars agree that the first readers of the Exodus narrative in its final form found themselves in a place or places of discomfort.

7 Another word for cry is murmuring.

8 All TWOT Lexicon references in this paper are drawn from BibleWorks 8 electronic edition.

9 BibleWorks (2008).

10 Strong 2001 (2199 - Ex. 2:23; 6817 - Ex. 5:8).

11 It can also have the meaning of "lodging" or "staying over", as in Genesis 19:2 (Strong 2001:574).

12 An interesting study could also be the unheard voice of creation, bearing in mind that the earth "cries" because of the way in which humanity abuses all its resources.

13 See Van der Walt (2014).