Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.39 n.1 Bloemfontein 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v39i1.2

ARTICLES

Dynamics between spirituality, leadership and life goals: a life narrative grounded theory study

G. E. Dames

Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology, Unisa E-mail: damesge@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In this article the relation between school leadership, spirituality, and ultimate life goals is considered. The objective of the study is to explore how leadership and spirituality are related and informed by ultimate life goals in schools. Spirituality is defined as a way of life of growing into human fullness that is grounded in a moral universe. Ultimate life goals represent ultimate values in the life of leaders and their deepest motivation for decisions and actions. Ultimate life goals originate from our contingent nature - as we move or change, we are constantly in need of a grounding/foundation. It gives direction and meaning in change and form through spiritual transformation. The life narrative research methodology was applied to explore the ultimate life goals and spiritual transformation in the life narratives of seven school principals in Roman Catholic private schools in Gauteng and two public schools in the Western Cape.

Key words: Life narrative research, Leadership, Spirituality, School leaders

Tref woorde: Lewensverhaal navorsing, Leierskap, Spiritualiteit, Skool leiers

1. INTRODUCTION

Life narrative research is an emerging research methodology at Radboud University in the Netherlands under the leadership of Prof Chris Hermans and Dr Theo SM van der Zee. The researcher collaborated with the aforementioned colleagues and some of their doctoral students, Dieter Praas1, Sandra JJB van Groningen2 and Jorien Copier3. Some of the views in this article were shared with the researcher by the aforementioned scholars.

This article focuses specifically on a collaborative qualitative research project between the Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology, University of South Africa (Unisa), Pretoria, South Africa, and the Department of Empirical Science of Religion, Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands (cf. Dreyer & Hermans 2014; Hermans 2013). A similar quantitative research project was carried out by Dreyer and Hermans (2014). The comparison between the research findings of these two projects are not described comprehensively in this article due to a lack of space, but should offer interesting insights for future research projects.

The initial research project in the discipline of Practical Theology at Unisa engaged members of the discipline of Practical Theology at Unisa in a three-day workshop in February 2012. Prof. Chris Hermans of Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, facilitated the research training workshop (Hermans 2012). This workshop was followed by a second training workshop (held in 2013) in the methodology of coding and the analysis of research data. The rest of the data collection and analysis was done by the researcher or author of this article. This is a pilot study and offers a framework for a larger sample for future research. The research findings cannot be generalised due to the small research sample.

In the following sections the researcher presents the main question, the secondary questions, and the objective of the research, followed by the underlying principles of the life narrative research model.

The researcher sought to answer the main research question: Do school leaders have spiritual life goals and is there a relation between school leadership, spirituality, and life goals? The secondary questions are: Are spiritual goals an ontological reality in the spirituality of the specific sample of school leaders? How much reality is there in spiritual goals? Can school leaders replace spiritual life goals with something else? How are spiritual life goals demonstrated in their workplace? The main objective of the project was to examine the relation between school leadership, spirituality, and ultimate life goals within South African schools. The objective was to explore how leadership and spirituality are informed by ultimate life goals in addressing challenges in schools.

Dreyer and Hermans (2014:2) explored appropriate types of leadership to deal with the systemic educational crisis of school leadership in South Africa and how these leadership types could respond to these challenges and complexities - with the objective to examine the relation between spirituality and school leadership. Similar research was done in New Zealand, based on the lived experiences of spirituality in principal leadership, but with a different aim, namely to explore its influence on teachers and their teaching activities (Gibson 2014). Suffice it to say that the intersection between leadership and spirituality has a comprehensive influence on the entire education or school system. The school crisis in South Africa reached high psychosomatic levels; it may even have reached pathological conditions and consequences. "Even school principals do not turn up for work: 41 000 teachers are 'school sick' daily" (Kusel 2019:1) (own translation).

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF THE RESEARCH PROJECT

Hermans (2013:165) explores the influence of spirituality on school leaders based on a theoretical framework4 and with a sample of school leaders in

South Africa. Hermans (2013:166) conceptualises spiritual transformation in a "religiously invariant way" with the notion that spiritual transformation is a "type of spiritual experience". So as to avoid the traditional default of contrasting religious and spiritual realities/experiences (for example, as religious and non-religious) in terms of five aspects, namely 1) existentially relevant normal and unexpected experiences; 2) unexpected-anomalous and existentially relevant-ultimate experiences; 3) spiritual experience as ultimate experiences - sometimes anomalous, but not always; 4) culturally grounded and ungrounded spiritual experiences; and 5) spiritual and religious experiences (Hermans 2013:167). One can argue that spiritual and ultimate experiences resonate with the dynamics between spirituality and life goals.

How are we to understand the dynamics between spirituality and life goals? Emmons (2005:737) may offer the answer to this question. He maintains that our search for "ultimate questions of meaning and existence, purpose and value" lies in personal goals.

In attempting to answer questions such as "Does life have any real meaning?" or "Is there any ultimate purpose to human existence?" implicit worldview beliefs give rise to goal concerns that reflect how people "walk with ultimacy" in daily life. In personal goals that participants have generated in past research studies, they report the ultimate concerns of trying to "be aware of the spiritual meaningfulness of my life," "discern and follow God's will for my life," "bring my life in line with my beliefs," and "speak up on issues concerning people who have been wronged" (Emmons 2005:737).

Research in general is not addressing the notion of life goals as a source of meaning in people's lives.

People often define themselves and their lives by what they are trying to do and by who they are trying to be. Spiritual and religious goals, above all others, appear to provide people with significant meaning and purpose (Emmons 2005:742).

Versteegh (2011:11) holds that human behaviour has to be structured in terms of the life goals people aspire to. Life goals relate to a higher reality and are grounded in real-life circumstances. Furthermore, spirituality is a search by modern men/women for life fulfilment (Versteegh 2011:11). Life fulfilment resonates with "ultimate experiences as subjective significance of absoluteness, finality and wholeness" (Hermans 2013:168). Spirituality is form making of everyday life in the light of the life goals people strive for - the impact of aligning life with an ideal (Versteegh 2011:11). Spirituality fosters the feeling of fulfilment, happiness, self-value, hope, optimism, and meaningful experience. The goals people strive for are ultimate concerns or ultimate life goals (Paul Tillich in Versteegh 2011:11). Ultimate experiences, in terms of Hermans (2013:169), are orientational (ultimate concerns regarding the self and others and the world - beyond the divided self) and transformational (the self's changes towards a more unified self - a process of changing the divided self). These orientational and transformational experiences in terms of spirituality, according to Gibson (2014:520), are "a complex and controversial human phenomenon". The meaning of these experiences are shaped and re-shaped by diverse perspectives and experiences.

Spiritual experiences are basically experiences of ultimate meaning which are existentially relevant and unexpected and occasionally objectively strange experiences regarding normal experiences (Hermans 2013:169).

Meaning-making practices foster spiritual goals in inspiring leaders to experience life as fulfilling, meaningful, and purposeful, despite difficult existential and situational conditions (Emmons 2005:742).

Goals that fulfil individualistic, but not collective or societal needs may ultimately lead to lower quality of life and to a worsening of interpersonal relationships (Emmons 2005:742-743).

Human beings experience themselves as divided, fragmented, a split between good will and bad actions, unhappy and not knowing how to become a better self (Hermans 2013:171).

To this end, Hermans (2013:170) applies the triadic model of Waaijman with a material object of spirituality -

the interaction between the self and a power (source, agency) beyond the self in which the interaction manifests itself as transformation of the self. Transformation is the formal object or perspective from which this relationship between self and agent (power) is perceived.

Waaijman (in Hermans 2013:170-171) regards this relation (material and formal dimensions of spirituality) as

a meaningful experience for human beings when there is movement, change, development, transition and process. The source of agency or power causes change in the human self [...] towards the ultimate meaning of the self (the true self).

The power of change is both the source and the goal of transformation.

If change in form does not lead to the desired state of ultimacy, the power of change is not considered to be spiritual (Hermans 2013:171).

Hence, spirituality is a search for and means of reaching beyond human existence. It creates

a sense of connectedness with the world and with the unifying source of life [....] an expression of people's profound need for coherent meaning, love and happiness. The need to create coherent meaning (in terms of wholeness, fullness, ultimacy) is inherent for our very existence as human beings (Cloninger in Dreyer & Hermans 2014:3).

Spiritual goals are an ontological reality in the spirituality of leaders -they are a given. The question is: How much reality is there in spiritual goals? Special goals in life can never be realised by oneself. We are responsible for those goals, but unable to fulfil them; it may be expected of us to strive for goals. The following questions arise: Can life goals be replaced and who is responsible for spiritual life goals? (Emmons 2005); Of all the goals that people strive for, which ones really matter? and Which goals provide the most sense of meaning and purpose? (Emmons 2005:732).

3. PRINCIPLES OF LIFE NARRATIVE RESEARCH

The underlying principles of the proposed life narrative research are described in this section. How are we to understand the relationship between leadership, spirituality, and life goals?

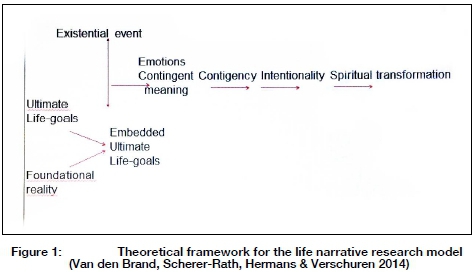

The researcher sought to understand the dynamics between the following concepts: leadership, spirituality, and ultimate life goals in situations of change or strife in schools. The researcher explored how school leadership and spirituality, grounded in implicit or explicit ultimate life goals, relate to school events and are simultaneously formed, transformed, and enacted through situational, existential, and spiritual experiences of change in the process of forming a new leadership identity or agency. This is an explorative qualitative empirical research study in selected schools in South Africa. Both the theoretical exploration and the empirical framework (Van den Brand, Hermans, Scherer-Rath & Verschuren 2014; Saldaria 2013) consist of a philosophical (Ricoeur 1991), a psychological (Hermans 2012; Van den Brand et al. 2014), a practical theological (Scherer-Rath 2007; Ricoeur 1991) and a spiritual perspective (Waaijman 2002). The philosophical perspective focuses on the self - understood as narrative. The psychological perspective illuminates life narratives as motivators of the feelings, meanings, and actions of school leaders. The practical theological perspective elaborates on the contingency of life stories. The spiritual view explores spiritual transformation in the life narratives of school leaders. Together, the four perspectives represent the theoretical framework for the life narrative research model, as illustrated in Figure 1 above.

The function of the life narrative model is to illustrate the role of spiritual transformation in relation to leadership. The model is an interpretation of spiritual transformation. It is worth noting that Dreyer and Hermans's (2014:7) research indicate that school leaders in South Africa "mostly agree with a transformative leadership style". They found a significant correlation between the latter and certain personal, professional, religious, and spiritual characteristics and conclude that these spiritual traits constitute a strong predictor for transformational leadership (Dreyer & Hermans 2014:7).

Narratives construct our life events, goals, and motivation in an order or a plot (Scherer-Rath 2014:81). Through our subjective experiences, we can build identity through our narratives (Scherer-Rath 2014:85). Narratives construct the meaning of how we experience everyday experiences; they are about the social construction of our reality (Scherer-Rath 2014:84; Berger 1976:30 in Versteegh 2011:2). Spirituality, however, is the manner in which we give form to our life as meaning making. Therefore, we have a need to reflect on our spiritual biographies.

The aim of this article is to link self-narratives with workplace and life choices that school leaders make. Self-narratives motivate school leaders to make certain choices that lead to certain types of actions, which are driven by their motives - their intentionality to act or to make decisions. The researcher sought to explore the types of choices that correlate with the self-narratives. Life narratives motivate our meanings, feelings, and actions. The researcher further sought to relate the self-narratives of school leaders with their spirituality and particular school challenges. The life narrative model in Figure 1 is based on different building blocks to demonstrate how school leaders experience life's challenges in the school context. The researcher sought to explore the connections between what school leaders do as leaders and what they do as spiritual and value-based persons (Van den Brand et al. 2014:106).

Life narratives are always contingent. The notion of contingency is crucial in life narratives. It reveals how we create fragile meanings of understanding. These newfound meanings of understanding reveal how we understand ourselves in a certain order or orderly form. A break in our life order is characterised by a contingency - the unexpected events of life; they just happen; they need not happen, but they happen (cf. Figure 1). Therefore, we are in need of the reconstruction of our life narratives to reorder or reconstruct the different building blocks of our life narratives in a meaningful order (Scherer-Rath 2014:82,86; Van den Brand et al. 2014:104).

The researcher explored the contingency in school leaders' life narratives about moments of change or contingencies in their lives. Contingency is based on different life goals in and through situational, existential, and spiritual experiences (Scherer-Rath 2014:85). The researcher linked the self-narratives of school leaders with their intentionality in making choices. The researcher also examined which factors are crucially important to school leaders to motivate them to make choices and/or decisions and to act on them. Spiritual transformation is key in this instance (Hermans & Koerts 2013:209). It is reflected in changes in school leaders' choices, decisions, and actions as a way for them to be formed, to be enabled to lead a meaningful life, or be fulfilled (Scherer-Rath 2014:85). The life narrative building blocks provide a rich understanding of school leaders' life narratives or lived spiritualities.

The spiritual transformation5 model6 illustrates how meaning making can help to link elements of spirituality, leadership and biographical life narrative, that is, "how meaning attributed to existential events and how that meaning affects the intentionality of behaviour" (Van den Brand et al. 2014:105). Meaning making refers to the line of enquiry or reconstruction of a life narrative. Meaning making is based on two aspects. Firstly, how the researcher links each of the different life narrative building blocks to understand the change in a school leader's life narrative; and secondly an awareness that people get of who they are, and who they are in terms of their life narrative and spiritual fullness in moments of change (Scherer-Rath 2014:81, 85). In that change, there is always form so that people can attain understanding through form (such as joy or suffering) or discover their identity, mission, vision, or life goal (Van den Brand et al. 2014:104-105). Who we are as leaders affect our decisions and actions. Meaning relates to the levels of intensity of contingency and/or the depth of our decisions, choices, and actions. Hence, it relates to crisis events or incidents. "People shape their personal identity by reconstructing their life stories through assigning meaning to significant existential events" (Van den Brand et al. 2014:104). Meaning, identity, or values assist leaders in reaching spiritual fullness or ultimate life goals. "In life stories existential events and life goals are inherently related" (Van den Brand et al. 2014:105). Where do our ultimate life goals come from? As situationally, existentially, and spiritually contingent persons, we move from one position to another or simply change. We therefore need a grounding, a foundation beyond our own. This foundation can be either immanent or transcendent, active or passive. According to Frijda (2007 in Hermans & Koerts 2013), meaning is attributed by confronting existential events with personal goals (Van den Brand et al. 2014:105). It is worth noting the research findings of Gibson (2014:520ff) in this regard.

Spirituality ... includes personal, social-cultural and transcendent connectedness, meaning making about life and living, and a desire for greater authenticity, resulting in consistency between people's beliefs, moral-values, attitudes and their actions. The three principal participants believed their personal meanings of spirituality were intentionally and yet appropriately interwoven into a range of professional tasks, linked to characteristics of servant, transformational, moral and relational leadership styles, and contributed to their sense of resilience in the job. Most teacher participants perceived spirituality in their principal's leadership as influential through the quality of their professional character, competence and conduct.

4. EMPIRICAL RESEARCH DESIGN

The researcher based the data-collection method on the spiritual transformation model as described above.

In exploring the relationship between school leadership, spirituality, and ultimate life goals, the abovementioned spiritual life narrative research model was used. Jaco de Witt and Chris Hermans' (2013) interview guide for a semi-structured interview for ultimate meaning and spiritual development in life narratives of 25- to 35-year-old adults experiencing a quarter-life crisis was adapted for the South African school context.

In addition to semi-structured interviews, the data-collection techniques also consisted of a lifeline instrument in providing interviewees the opportunity to choose life-changing moments in their own life stories to explore the relation between leadership, spirituality, and ultimate life goals in the life narratives of seven school leaders.

Seven schools were identified in Gauteng and the Western Cape. The sample consisted of school leaders (school principals, vice-principals, and leaders in management) in Roman Catholic private schools, Anglican and private Christian (mostly high) schools in Gauteng, and two primary schools, a public and Roman Catholic school, in the Western Cape. Data-collection took place between October and November 2012.

Five interviews with school leaders in selected schools in Gauteng and the Western Cape Province were conducted by the author and two interviews were conducted by colleagues of the author, Proff. Dreyer and Buffel, in the discipline of Practical Theology at Unisa between November and December 2012. The interviews were recorded with a digital tape recorder and transcribed verbatim.

5. GROUNDED THEORY ANALYSIS

Grounded theory analysis, coding, and the different coding cycles are described briefly in the following sections. The researcher employed grounded theory analysis in search of new theory development. Grounded theorists emphasise causal relationships between data, and place data into a basic frame of generic relationships (Saldaria 2013:51-52). Grounded theory as an analytic

process involves meticulous analytical attention by applying specific types of codes to data through a series of cumulative coding cycles that ultimately lead to the development of a theory - a theory - 'grounded' or rooted in the original data themselves (Saldana 2013:51).

Coding helped to reduce the complexity of the observed phenomena by ordering and structuring the concepts, dimensions, aspects, sub-aspects, values, and categories in the data (Saldaia 2013:3ff.). The structuring of data helped the researcher to relate elements such as processes, phases, correlation, causes, and effects in the data. The analysis of the data was done through multiple coding cycles. First-cycle coding consisted of open coding, in vivo coding, and process coding to split or fracture the data into individually coded segments. Second-cycle coding consisted of axial coding and theoretical coding to consistently focus, compare, and reorganise the codes

into categories by prioritising them to develop 'axis' categories around which others revolve, and to synthesise them to formulate a central core category that becomes the foundation for explication of a grounded theory (Saldana 2013:51-52).

As mentioned above, Saldaia (2013) distinguishes between two phases of analysis. First-cycle coding is the process of initial coding that organises data in different categories and topics. Second-cycle coding helps to develop a sense of categorical, thematic, conceptual, or theoretical organisation of first-cycle codes (it is a further reduction and structuring of data) (Saldana 2013:3ff.). Axial coding as a form of selective coding formed an important part of the study. Axial coding is the process of relating codes (categories and properties) to each other via a combination of inductive and deductive thinking (Saldaria 2013:218-223). The objective with selective coding was to bring more structure to the list of codes. This was probably the most difficult phase of the research, but also the most rewarding. Theoretical coding was applied during the second-cycle coding phase to capture the central variable that linked all the different codes and categories into theory (Saldaria 2013:223-229).

Theoretical coding is like an umbrella that covers and accounts for all other codes and categories formulated thus far in grounded theory analysis. Integrating the different sets of codes helped to find the primary theme of the research. The central or core category consists of all the products of analysis condensed in a few words to explain what this research is all about. All categories and subcategories are linked with the central or core category - the greatest explanatory relevance - which addresses the questions: how? and why? (Saldaia 2013:223).

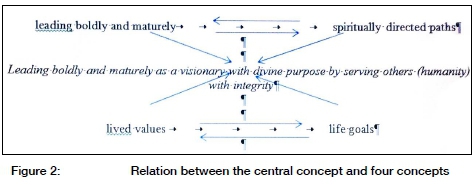

The concepts that emerged from the analysis of the interviews and a potential theory for school leadership based on the data are described in the next sections. The research was done in two phases. Phase 1 was carried out by all of the members of the discipline of Practical Theology at Unisa and Phase 2 was conducted by the author. Categories emerged from the analysed interviews during the cumulative coding cycles in the first cycle of open coding and in the second cycle of axial or selective coding. In the first cycle of Phase 1, the categories IF taking the right decision and self-belief (believed in myself) and determination (perseverance) THEN being blessed; and IF being successful in making my vision clear THEN strengthen my self-confidence, were integrated by the core variable of determination and self-belief of a school leader. In the second cycle of selective coding, the core variable determination as self-belief was informed by the notion of leading with determination and confidence. In the first cycle of Phase 2, the categories bold and mature, spiritually directed paths, and lived values and life goals were integrated by the core variable of leading fearlessly with intent by a school leader. In the second cycle of selective coding, the core variable leading fearlessly with intent was enriched by the notion of leading boldly and maturely as a visionary. Eventually, during the process of theoretical coding, the concept of leading boldly and maturely as a visionary with divine purpose by serving others with integrity emerged as a core concept. This core concept integrated the data obtained through the interviews in the research sample.

Theoretical codes integrated all the different codes to establish the primary or core theme of the research (Saldaia 2013:223). In the open coding cycle, the researcher used the theoretical code of leading fearlessly, which revealed a clear notion in the interviews. In the selective coding cycle, the researcher made use of the theoretical code of leading boldly and maturely, which integrates the different leadership practices practised by the school leaders in the sample.

6. CONCEPTS THAT EMERGED FROM THE ANALYSED DATA

The practice of leading a school comprises, firstly, determination, then self-belief with integrity, which has a relation to the school's vision and community, and, finally, leading the school boldly and maturely as a visionary with divine purpose by serving others (humanity) with integrity. The initial two concepts and, in the second phase, four concepts that emerged from the analysis of all the interviews in the two cycles of analysis are presented below. Multiple categories emerged from the interviews, which the researcher finally arranged in a core theory.

Phase 1: Leading schools with confident determination

Category 1: Self-belief (self-confident)

DEFINITION: Self-belief is the deep personal confidence manifested in the action of successfully achieving something that can withstand any challenge.

RESPONDENTS' COMMENTS

• Self-belief is believing in myself in the sense of being able to realize something. In other words: self-belief is action oriented. It will show itself. (P 6:8-9, 13, 16).

• Self-belief is the result of personality. (P 6:8-9, 13; P 2:36; P 3:4).

• It can be contested or challenged, but if it is part of my personality (character) the person will stand that challenge. (P 6:20).

• Self-belief can be strengthened by being successful. So when the leader is successful at making clear his vision, this will boost his or her confidence. (P 2:19; P 6:38).

Category 2: Determination

DEFINITION: Determination is the attitude of perseverance with courage, which - in situations that one can control - puts the vision that drives this determination into deeds without delay, although others will contest the authenticity of the person.

RESPONDENTS' COMMENTS

• Determination is characterised by perseverance and persistence in the sense of not letting go. (P 6:29; P 3:5; P 5:42; P 7:4).

• Instant determination: Not hesitant: put into deed without delay (P 6:9, 17).

• In-control determination: If else no achievement: is conditional to be able to put into deeds (P 6:20; P 4:13; P 5:9).

• Vision-oriented: without a purpose no orientation what to do (P 6:38; P 2:20; P 4:17).

• Contested (challenged) determination: others will question the correctness/authenticity? of your vision (P 3:7; P 4:15; P 5:6, 32).

• Competitive determination: to take on the fight when challenged with courage: "You're either driven or your not - do not give up!" (P 2:22-23).

• Learning from failure (P 3:5-7).

Phase 2: Leading boldly and maturely as a visionary

Category 2.1: Leading maturely and boldly

DEFINITION: Transparent and fearless leadership transcending selfish goals to build relational partnerships for shared responsibility.

RESPONDENTS' COMMENTS

• When speaking out about things you feel strongly - it's no good skirting around them (P 3:17).

• When leadership becomes much more relational than administrative (P 3:42).

• When less self-focused and more other-focused (P 3:33; P 7:3, 4).

• When leadership is transformed to become more realistic; seeing more deeply; can see behind the situation (P 2:35; P 4:47; P 6:35).

• Leadership is firm and fair - "like lions we are fearfully made" to provide in others' needs, to offer peace and refuge (P 2:16-17, 39).

• "Refined like gold in fire - leadership; life tremendously altered" (P 7:2, P 3:8, 16, 20).

Sub-category 1.1: Proactive awareness

DEFINITION: Proactive awareness is listening and learning in defining moments to take charge of new situations.

RESPONDENTS' COMMENTS

• When being aware of similar challenges in a previous situation to deal with new issues (P 3:10, 12, 19; P 2:34).

• When open to listen/learn, despite being angry at the time (P 3:6; P 4:14).

• To evaluate whether you are causing, for instance, conflict and if you are proactive in resolving it (P 2:8).

• To do introspection and to be transformed as a leader in becoming relevant to people in a new situation/context (P 3:35).

• Praying, waiting and listening before making a decision (P 5:44).

• When a decision becomes the most defining moment in your life (P 7:4).

• When good reflection becomes an encounter as in a sense of worship to honour God (P 7:4).

Sub-category 1.2: Taking charge

DEFINITION: Taking charge is the ability to recognise sociocultural and political barriers to transform destructive intentions into new opportunities.

RESPONDENTS' COMMENTS

• Realisation of a new vision and hope to transform destructive intentions into new opportunities (P 5:18).

• When challenged to take charge, and to make it happen, as opposed to letting it happen (P 4:11).

• When forced to deal with the unknown, to deal with your fears (P 7:3).

• To face challenging times, opposition, rejection, and suffering (P 5:29; P 4:15).

Category 2: Spiritually directed paths

DEFINITION: Spirituality is the inner presence of God, which manifests in leadership through actions, values and transformation.

RESPONDENTS' COMMENTS

• Spirituality is an understanding and belief that God is incarnate in this room, in this school, in this community (P 4:29).

• Spirituality fosters a sense of direction how to deal with personal problems; emotionally and spiritually (P 3:31; P 2:13, 21; P 7:3).

• A spiritual path fosters fairness to children (P 3:31, 36; P 2:26).

• Spirituality is the integration of integrity and trust in decisions and actions (P 5:46; P 7:4).

• Grounded in a higher reality: instrument of God (P 4:40).

• Cannot depend on myself to do what I do without the strength of the Holy Spirit (P 7:3-4).

Category 3: Lived values

DEFINITION: The embodiment and enactment of healthy (Christian) values to serve others by creating a culture of discipline and tolerance.

RESPONDENTS' COMMENTS

• "Church [parental] values marked-out my path" (P 4:5; P 6:1, 4).

• When a school demonstrates friendliness, honesty, sincerity, integrity respect and tolerance towards others and other religions (P 2:1-3; P 6:2, 3).

• When leaders embrace a healthy value system that serves children and not their own benefits.

• Where people are living a disciplined life - their theology expressed in daily life when integrity, righteousness and goodness lived out in the community (P 3:1).

• The alignment of personal values and the values of the school and the values of the church community (P 4:1; P 2:3).

Sub-category 3.1: Serving humanity

DEFINITION: Serving humanity is to demonstrate solidarity with poor communities by breaking barriers, changing paradigms, and transforming society.

RESPONDENTS' COMMENTS

• When envisioned that "every child in this school has to do some form of community service as a duty performed" (P 4:34).

• Breaking barriers, changing paradigms and transforming society (P 5:18, 43).

• When wealthy church schools' primary responsibility is to create schools for the poor: "to serve well in that community" (P 4:32, 37).

• When children serve God well in church and state - in the world to make a difference - ultimately for God! (P 3:33, 40; P 2:4-5, 40).

• When leadership is transformed in terms of God to become less self-focused and more other-focused (P 7:4).

Category 4: Life goals

DEFINITION: Life goals are God centred, grounded in spirituality and manifest in transformation - by serving God and communities.

RESPONDENTS' COMMENTS

• When life goals are born out of a situation (P 2:12; P 3:24).

• When one's goals are aligned to your spirituality (P 3:26; P 47; P 5:46).

• When one's growth as a person is characterized by goals in life - it counters depression and complacency (P 2:28-29).

• When one is living with a purpose: "God predetermined what He wanted me to do" (P 7:3).

• When your primary goal is to serve God in a community in need (P 3:37, 40; P 4:37).

The core, enriched concept that integrated all categories is: leading boldly and maturely as a visionary with divine purpose by serving others with integrity. All these categories feature in one way or the other in the context of the research sample. Each individual school context shapes or determines specific leadership characteristics, although many leaders may demonstrate the same kinds of leadership traits. These categories of leadership in schools that are inspired by bold and mature visionary leaders, especially in terms of the leaders' (transformational) leadership, spirituality, and ultimate life goals with reference to school challenges and poor communities, offer new perspectives for practical theology.

For instance, Dreyer and Hermans (2014:8) found that two spiritual traits, self-directedness and self-transcendence, are dominant indicators for transformational leadership. They conclude that

transformational leadership involves an attitude towards the emerging future (in terms of the mission, vision, inspirational motivation, and trust).

The different categories in this article are an encapsulation of the aforementioned traits. Furthermore, our research indicates a similarity with Dreyer and Hermans's (2014:8) research finding that spiritual traits are more dominant predictors of leadership than religious characteristics. Hence, the school context may function as "a source of agency or power", according to Waaijman (in Hermans 2013:170-171), by transforming the human self in terms of the ultimate meaning of the self (the-true-school-leadership-self). Meaning, wholeness, fullness, and ultimacy constitute the essence of our existence as human beings (Cloninger in Dreyer & Hermans 2014:3). We can, thus, concur with Dreyer and Hermans (2014) and Hermans (2013) that spirituality or lived spirituality is broader in scope than "classical" religious traits and that spiritual traits directly relate to and impact transformational leadership, particularly in the context of this article.

7. A GROUNDED THEORY FOR SCHOOL LEADERSHIP

All four concepts described earlier are related to the central concept of leading boldly and maturely as a visionary with divine purpose by serving others (humanity) with integrity. The following model illustrates the relation between the central concept and the four concepts identified earlier, as a grounded theory for the practice of school leadership in South Africa. The theory for the practice of school leadership in the South African context consists of four concepts (see the model) that are in close relation to the central concept of leading boldly and maturely as a visionary with divine purpose by serving others (humanity) with integrity, which integrates all the categories and concepts. This model also shows the anthropology and ontology (being and doing functions) of school leadership and the consequent practices of leaders in serving children, parents, and their communities.

8. CONCLUSION

The practice of leading schools in the South African context consists of four concepts that feature in close relation to the core concept of leading boldly and maturely as visionaries with a divine goal to serve others with integrity, which integrates all the concepts and categories. This model also demonstrates that there is indeed an ontological relationship between leadership, spirituality, and (ultimate) life goals. The data also shows how the anthropology and ontology of leaders are transformed by their spirituality, life contingencies, and school contexts. All the concepts and categories in the data demonstrate a strong aptitude for bold and mature leadership that is formed by a clear vision and transformed through divine spirituality within difficult existential defining life events to fulfil ultimate life goals grounded in serving others with integrity.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Copier, J. 2019. Breaking and sharing stories: leadership and ultimate meaning in Catholic primary schools. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Nijmegen: Radboud University, [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.ru.nl/personen/copier-j/ [17 April 2019]. [ Links ]

De Witt, J. & Hermans, C.A.M. 2013. Interview guide for a semi-structured interview for ultimate meaning and spiritual development in life narratives of 25- to 35-year-old adults experiencing a quarter-life crisis. Unpublished. [ Links ]

Dreyer, J.S. & Hermans, C.A.M. 2014. Spiritual character traits and leadership in the school workplace: an exploration of the relationship between spirituality and school leadership in some private and religiously affiliated schools in South Africa. Koers: Bulletin for Christian Scholarship 79(2):1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/koers.v79i2.2136 [ Links ]

Emmons, R.A. 2005. Striving for the sacred: personal goals, life meaning and religion. Journal of Social Issues 61(4):731-745. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00429.x [ Links ]

Gibson, A. 2014. Principals' and teachers' views of spirituality in principal leadership in three primary schools. Educational Management Administration and Leadership 42(4):520-535. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213502195 [ Links ]

Hermans, C.A.M. 2012. The life narrative sequence model: narrative reconstruction of life story after unexpected event (Paul Ricoeur). Paper presented at the Theological Research into Lived Spirituality in Life Narratives: From Theory to Empirical Research Workshop in the Department of Practical Theology, Unisa, 9-12 February. [ Links ]

Hermans, C.A.M. 2013. Spiritual transformation: concept and measurement. Journal of Empirical Theology 26:165-187. https://doi.org/10.1163/15709256-12341275 [ Links ]

Hermans, C.A.M. 2014. Narratives of the self in the study of religion: Epistemological reflections based on a pragmatic notion of weak rationality. In: M. de Haardt, M. SchererRath & R. Ruard Ganzevoort (eds). Religious stories we live by: narrative approaches in theology and religious studies. (Leiden: Brill), pp. 34-43. [ Links ]

Hermans, C.A.M. & Koerts, E. 2013. Towards a model of influence of spirituality on leadership: empirical research of school leaders on Catholic schools in the Netherlands. Journal of Beliefs & Values: Studies in Religion & Education 34(2):204-219, DOI:10.1080/1 3617672.2013.801685. [ Links ]

Kusel, A. 2019. Selfs shoolhoofde daag nie op vir werk: 41 000 onderwysers daagliks 'skoolsiek'. Die Burger, April 9: page 1. [ Links ]

Praas, D. 2018. Zusammen sind wir ganz bunt und eigentlich ganz stark! Narrative identitätsentwicklung in fusionierten pfarreien. Berlin Münster, LitVerlag. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.lit-verlag.de/isbn/3-643-14026-5 [17 April 2019]. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, P. 1991. Life in quest of narrative. On Paul Ricoeur. Narrative and interpretation, edited by D. Wood. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.5840/philtoday199135136 [ Links ]

Saldana, J. 2013. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles: Sage. [ Links ]

Scherer-Rath, M. 2007. Contingentie en religieus-existentiële zorg. Tijdschrift voor Geestelijke Verzorging 10(42):28-36. [ Links ]

Scherer-Rath, M. 2014. Narrative reconstruction as creative contingency. In: M. de Haardt, M. Scherer-Rath & R. Ruard Ganzevoort (eds). Religious stories we live by: Narrative approaches in theology and religious studies. (Leiden: Brill), pp. 81-88. [ Links ]

Van den Brand, J., Hermans, C., Scherer-Rath, M. & Verschuren, P. Scherer-Rath, M. 2014. An instrument for reconstructing interpretation in life stories. In: M. de Haardt, M. Scherer-Rath & R. Ruard Ganzevoort (eds). Religious stories we live by: narrative approaches in theology and religious studies. (Leiden: Brill), pp. 169180. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004264069_014 [ Links ]

Van Groningen. S.J.J.B. 2019. Fostering spiritual discernment in Catholic secondary school management teams, Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Nijmegen: Radboud University. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.ru.nl/ptrs/crcs/phd-projects/internal-phd-projects/ [17 April 2019]. [ Links ]

Versteegh, G. 2011. Emoties in het levensverhaal: een narratieve benadering van zingeving. Unpublished master's thesis. Nijmegen: Radboud Universiteit. [ Links ]

Waaijman, K. 2002. Spirituality: forms, foundations, methods. Leuven: Peeters [ Links ]

Date Published: 24 June 2019

1 Praas completed his research and graduated in 2018. The title of his dissertation at the time (2015) was Telling our story as a local church: strengthening of the narrative identity of communities of congregations in the diocese of Aachen. He published his dissertation in book form under the title, Zusammen sind wir ganz bunt und eigentlich ganz stark! Narrative Identitätsentwicklung in fusionierten Pfarreien.

2 Sandra van Groningen's (2019) research focuses on personal belief systems, school leadership, and school identity in Catholic secondary schools with as title, Fostering spiritual discernment in catholic secondary school management teams.

3 Copier's (2019) research project deals with the relation between leadership and ultimate meaning with as title, Breaking and sharing stories: leadership and ultimate meaning in Catholic primary schools.

4 It is worth noting Hermans' (2013:182) research findings of five types of transformation. "The first three types were confirmed in his research findings, namely 1) a form-given type of transformation-awareness that non-existence or existence in time and space is offered as a possibility or non-possibility for existence to the self; 2) re-forming type of transformation-awareness of a new chance to develop a true self, or restore the true, original self, or the loss of one's true self; 3) a beyond-form type - the self unifies with ultimate reality; or absolute abyss or non-possibility of unification with the ultimate. Two types of transformation redefined as transparent-path merged in his research, namely 1) a con-forming type - human awareness of a path to follow to become their true selves or not seeing a path or spiritual example to follow; and 2) transparent-form type - the ultimate becomes so transparent in the self that it radiates through the self or not experiencing the gift of the presence of ultimate reality in the self".

5 "Spiritual transformation is defined as the process of reaching self-awareness to unify the divided self. This drive to unify the divided self gives spiritual transformation existential relevance: human beings experience their form of existence (self) as unbalanced, split, heterogeneous (disequilibrium), or (conversely) they become aware of how they can achieve balance, greater unity" (Hermans 2013:182).

6 Based on the model of the psychologist Frijda (in Van den Brand, Hermans, Scherer-Rath & Verschuren 2014:104-105).