Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.38 n.2 Bloemfontein 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v38i2.8

ARTICLE

Towards doing practical integral mission: A Nazarene Compassionate Ministries (NCM) reflection in Africa

Prof. V. MageziI; Mr. C. MutowaII

IFaculty of Theology, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. E-mail: vhumani.Magezi@nwu.ac.za

IIRegional Coordinator, NCM Africa, Nazarene Centre, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The concept "integral mission" denotes the contribution of churches in helping people and communities with material resources. It remains unclear as to how this widely held theological concept is done practically. At a theological level, there has been a general silence on reflection regarding how organisations can practically do integral mission. Using an institutional theological understanding of compassionate ministry within the church of the Nazarene Compassionate Ministries (NCM), this article demonstrates the convergences and divergences that may arise in an organisation as it attempts to implement integral mission interventions. It is also an empirical case study of leadership and grassroots (implementation) level staff to show the differences that may exist and weaken integral mission efforts. At a theory formation level, the article contributes to understanding the dynamics of implementing integral mission.

Keywords: Practical integral mission; Implementing integral mission; Integral mission; Nazarene Compassionate Ministries

Trefwoorde: Praktiese integrale missie; Implimentering van integrale missie; Integrale missie; Nazarene Compassionate Ministries

1. INTRODUCTION

Despite the generally held position that integral mission is the legitimate and responsible way of doing Christian mission, it remains somewhat unclear as to how this is done practically. Hence, this subject is worth examining from a practical case study perspective. The article proceeds to examine this topic by first sketching the context of integral mission. This is followed by an outline of Nazarene Compassionate Ministries (NCM). After establishing these two positions, the article then considers a case study based on empirical information.

2. CONTEXTUAL SKETCH AND PROBLEMATIZING OF THE ISSUE

Over the years, churches and Faith-Based Organisations (FBOs) have played a significant role in the social development and transformation of people's lives (Padilla 2004; Birdsall & Kelly 2005; Kelly et al. 2010; Weekes 2017; Foster 2010; Yates 2003; Magezi 2007; 2012; 2017; 2018). Chester (2004:63) mentions that terms such as "integral mission", "holistic mission" or "ministry", "Christian development", "compassionate ministry", "transformation", or "church-driven development" denote the role of churches in helping people and communities with material resources, as opposed to solely evangelism. These terms denote a Christian ministry that is concerned for the whole person. In this discussion, the term 'integral mission' will be used as the representative term.

The position on integral mission across the globe was articulated at the Lausanne Congress in 1974, where it was stated that

social activity is the consequence of evangelism, social activity can be a bridge to evangelism, and social activity is the partner of evangelism. Social action, then, can precede, accompany or follow evangelism" (Chester 2004:61-62).

The Micah Network (2001:1), an important movement born out of the integral mission movement, explains:

Integral mission or holistic transformation is the proclamation and demonstration of the gospel. It is not simply that evangelism and social involvement are to be done alongside each other. Rather, in integral mission our proclamation has social consequences as we call people to love and repentance in all areas of life. And our social involvement has evangelistic consequences as we bear witness to the transforming grace of Jesus Christ.

Christians across the divide agree that integral mission is the appropriate way of doing Christian ministry (Bosch 1991:512). Having been involved in integral mission discussions since the Lausanne 1974 Conference, Padilla (2004:22) is convinced that the proliferation of Christian Development Organizations (CDOs) is attributed to integral mission decisions that started in the 1960s and reached a peak at the Lausanne Congress in 1974. Padilla (2004:22) notes that the agreement among Christians on the notion of integral mission is undisputed and that the practical impact of that theological position is evident in an explosion of church-driven developmental initiatives. Padilla (2004:22) adds that the outburst of the so-called Para-church organisations, special-purpose groups or voluntary societies, especially after World War II, were heavily dependent on the churches' volunteer help. They became a crucial faith-based means whereby the people of God, regardless of race, social class, or gender, participate in Kingdom work globally.

Despite the agreed position, impetus and claimed effects of integral mission, the notion of integral mission has, to a large extent, remained a broad heuristic framework lacking clarity on how it can be done practically. The regrettable result of this situation is, among other things, that deep theological reflection on how integral mission may practically be implemented and lived has been ignored, while individuals focus on doing whatever they do in the name of integral mission. Stott's (1996 ix-xii) exposition warns that, since the Lausanne covenant and Manila Manifesto, it is likely that a younger generation of Christian leaders is rising and is unfamiliar with the important theological and missiological thinking incorporated in these important documents of integral mission. Myers (2010:120), who has been theologically engaged in integral mission for over three decades together with other theologians such as Padilla, Stott, Samuel, Sugden and many others, observes that two aspects characterise the current lacuna in integral mission. First, holistic mission (evangelism and social action) is now a historical footnote. Second, people and organisations are simply getting on with transformational development (integral mission) with hardly any or no reflection. Myers (2010:120-122) further notes that, while holistic mission was embraced post-1980s with the theological foundation laid at Lausanne 1974, there has been no further conceptualisation and theological understanding of how things would work. He asks the question: What does it mean to say "get on with holistic mission" both conceptually and operationally? He explains: it appears that, once Christians agreed on the gospel validity of both evangelism and social action, they stopped working conceptually and theologically. Myers (2010:121) laments the deplorable state of holistic mission since 2010, stating what has not happened:

No new volumes of case studies have been published in the last ten years. There are very few new books on transformational development. There are very few serious programme evaluations that are genuinely holistic. There is very little, if any, serious research by Christian practitioners - very few PhD studies, and almost no academic research into transformational development. There is very little new theological reflection; we are resting on the excellent work done in the 1980s. There is no new ecclesiology, and yet the question of the relationship between the Christian relief and development agency and local churches remains unclear. The bottom line is this: for the last twenty years, evangelical holistic mission activists have acted. They've gone out and done transformational development. Doing is good. But there is more to doing than just acting.

The above situation reflects at least two gaps. First, it reflects a dearth and a shelving of serious theological reflection, as no new research is being done. A kind of integral mission theological fait accompli. Second, it reflects some kind of integral mission operational "black box", a vacuum on operational understanding.

Within FBOs or churches, the translation of the high-level theological concept of integral mission to practical congregational (grassroots) level has remained assumed and unexplained. Churches and theologians have been encouraged to get on with work. Sadly, the mentality of getting on with work has, among other things, contributed to making Christian work (integral mission) undistinguishable from other social or development work. The role and place of churches in integral mission is becoming blurred, as secular organisations conduct similar activities. In such a situation, the question is: What is the distinctiveness of integral mission, or should it be distinguished in the first place? The challenge in integral mission language is that, although Christian organisations such as World Vision, Tearfund and many other Christian organisations view churches as central to their strategy, it is done for pragmatic reasons, namely that, where the poor people are, the church is and remains present (Magezi 2012:1-8; 2017: 1-5; Sugden 2010:31-36).

Sugden (2010:31-36) observes that many Christians and Christian development agencies are either critical of the church or wish to remodel the church in their own image as centres of development, or view their own work as the essential addition to the work of churches to enable them to be holistic. This poses a challenge to Christian organisations. The question is: What should be the nature of discipleship and Christian community in order to address all the deformation of sin expressed in the experience of poverty and injustice? Sugden contends that the use of churches in development should not be for pragmatic reasons. Churches should not be viewed as instruments and vehicles or channels for development by virtue of their proximity to the community, but rather as possessing a unique differentiating Christian transformation framework compared to that of other development organisations (Magezi 2017). How does a child sponsorship programme by Plan International as a secular organisation differ from the one by Nazarene Compassionate Ministry as a Christian organisation? Stated differently, should the programmes be different? How? Why? This lack of clarity on the practicality of integral mission makes it operationally questionable and suspicious as a concept. Thus, while FBOs are the most prominent manifestations of civil society in Africa and other parts of the world responsible for integral mission interventions, they lack adequate social scientific analysis (Magezi 2018:15; Mati 2013:2). Grey issues include aspects such as: What is the practical nature of integral mission? How could integral mission be implemented in such a way that aid is not used for proselytizing people? What is the role of local churches and denominations in integral mission, particularly in development initiatives (Raistrick 2010:138-148)?

These grey areas in integral mission are not necessarily new. These issues have been debated to a great extent. Three responses emerged from these debates. First, some theologians have opted to shelve the reflection and debate, arguing that debating diverts people from the actual work; hence, they ignore critical reflection. Second, in many instances, the reflection has superficially lacked significant theological depth. Third, at evidence level, hardly any in-depth work has been performed with scientific rigour to provide convincing models of churches' integral mission work to demonstrate its efficacy. The work has, to a large extent, been micro, altruistic and fragmented, thus lacking in-depth scientific rigour to provide convincing models.

The above grey areas arguably indicate a need for organisations involved in integral mission to reflect on what integral mission practically means for them and how it should be theologically conceived. This challenges us to reflect on a theology of holistic mission at organisational level rather than in general theoretical terms. Thus, if integral mission is to be translated from theory to practice in a deeply theological manner, while simultaneously developing models of practically "doing it", it should be considered at organisational level. It is critical to examine how a particular organisation understands integral mission at both institution and grassroots level (grassroots implementation at congregational level). This analysis could shed some light on practically doing holistic mission. Such an analysis would reveal how the broad understanding of integral mission could be translated to grassroots communities and congregations. The way in which theology is done at academic theoretical level differs from that at congregational practice level. Yet, theory and practice should cooperate. Bowers (2009:91-114) and Tiénou (1990:73-76), writing within the context of African theology and ministry, rightly advise that the Christian community is the defining matrix of ministry, with its needs and expectations, its requirements and preoccupations. This is particularly important in Africa because, as Bowers (2009:91-114) observes, the intellectual preoccupations are sometimes at a tangent with what is practically happening in the lives of people on the ground. The intellectual project often does not reflect the needs and practicalities of church and ministry at congregation level.

One organisation that is worth examining on integral mission is the Church of the Nazarene, with its deep Wesleyan integral mission heritage. The denomination does not use the phrase "integral mission" to denote its holistic ministries, but rather the word "compassionate". The holistic ministries are called compassionate ministries and they fall under the ministry arm called Nazarene Compassionate Ministries (NCM). The NCM is a denominational ministry focusing on social action, which also resembles a faith-based Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO). It manages schools, hospitals and other compassionate activities. Its motto is "Building bridges for spiritual and social transformation" (Mutowa 2017:1). Raser (1998:12), a theologian of the Church of the Nazarene, describes the establishment of NCM in 1984 as a reforming process within the Church of the Nazarene, where the denomination is going back to its foundational principles of being compassionate. However, Raser (1998:2) observes that there is a weak theology of compassionate (holistic) ministries within the Church of the Nazarene. Therefore, it is pertinent to consider the denomination's theological foundation that is driving NCM. In doing so, it is important to probe how this theological foundation is integrated within NCM praxis as a component of integral mission of the denomination. Thus, the following question is explored: What is the theological understanding of integral mission (compassionate ministry) driving NCM at institutional leadership and grassroots members? How could this understanding be a window to gain insight into integral mission implementation dynamics?

3. INTEGRAL MISSION (COMPASSIONATE MINISTRY) WITHIN THE CHURCH OF THE NAZARENE

The formation of the Church of the Nazarene occurred at the turn of what is called the golden era of holistic mission, that is, at the end of 1800 (Andrews [s.a.]:1-17; Woolnough 2010:3-14; Samuel & Sugden 2003:71; Samuel 2002:27-28). The Church of the Nazarene was officially established in 1908, although the activities of uniting the various holiness movements started towards the end of 1800. The impetus from the golden era of holistic missions influenced compassionate care developments within the holiness movements, which contributed to the establishment of the compassionate ministries when the church started in 1908. The Edinburgh 1910 conference and the post-Edinburgh activities coincided with the establishment and strengthening of the various mission boards within the Church of the Nazarene (Chapman 1926:32). However, the rise of the dichotomy between social gospel and evangelism in the 1920s and the general economic decline due to the great depression heightened premillennial theology. Evangelicals focused on evangelism and downplayed social involvement. This period saw the decline of resources in the Church of the Nazarene, challenging the church to concentrate on its mission's approach by focussing on medical and education missions as a way of concentrating and prioritizing resources investment (Gilliland 1998:61-67; Langmead 2012:1-8; Nazarene Compassionate Ministries Magazine (NCMM) 2007:2; Crocker & Juarez 1996:6; Nazarene Archives Inventories [s.a.]:1-2; Church of the Nazarene Manual 2013-2017:34; Ingersol 1998:2).

During the post-World War I period and the resultant emergence of human needs, there was a renewed focus on holistic care. Post-World War II developments challenged evangelicals to refocus on holistic mission. In the Church of the Nazarene, Smith's writing challenged the church to strengthen its compassionate ministry. This challenge and subsequent renewed focus resulted in the Lausanne 1974 covenant and subsequent conferences into the 1980s. During this period, the Church of the Nazarene strengthened its compassionate work, resulting in the establishment of the Pastors' Children Education Program in 1983 and the Hunger and Disaster Fund at approximately the same time. However, a significant development in the history of the Church of the Nazarene was the establishment of the NCM Coordination office in 1984. From the 1980s to date, holistic mission was embraced within the denomination as the appropriate way to do missions (Monterroso [s.a.]:1-11). NCM has expanded to over 160 countries where the Church of the Nazarene has presence and is continuing to intensify its compassionate work.

Raser (1998:12) explains that the period from 1975 to 1998 and beyond characterises, what he calls, a period of "beating back amnesia" regarding holistic ministry (compassionate ministry) within the Church of the Nazarene, as the denomination reclaimed its historical compassionate history. Sadly, this progress and renaissance of compassion ministry in the Church of the Nazarene has not been matched by deep theological reflection. Raser (1998:12) rhetorically questions:

To what extent has it (compassionate renaissance) been, and is it being informed by careful theological reflection upon our (Nazarene) tradition and its sources? Is it mostly a sort of "intuitive activism" rooted deeply in our dimly remembered past, but not carefully grounded in the theological sources of our movement? And has the theological rationale for compassionate holiness been clearly communicated to our people? Can the current situation possibly be characterised as a renaissance of compassion in search of a theology?

Raser's comment suggests that the Church of the Nazarene compassionate ministry renaissance is hugely intuitive with hardly any theological depth. The weakness was also noted in the Church of the Nazarene's ecclesiology regarding compassionate ministries. Latz ([s.a.]:10) recommends examining the church's ecclesiology and the theology of holistic mission. While compassionate ministries exploded within the Church of the Nazarene to spread across the globe after the establishment of the NCM Coordination Office in 1984, what remained unclear is the question as to what extent this explosion was matched, supported and complemented by thorough theological reflection within the denomination. In order to answer this question, this article deals with the following issue: What is the theological understanding of integral mission (compassionate ministry) driving NCM at institutional leadership and grassroots members? How is this NCM theology understood across the organisation from the top (leadership) to grassroots implementation levels?

4. METHODOLOGY

The empirical data was collected at two levels: NCM regional coordinators in Africa, representing leadership and implementing churches, and NCM staff in Swaziland, representing grassroots implementers. A total of 28 Africa NCM coordinators participated in a consultation and in interviews. Six focus group discussions were held in Swaziland with a total of 58 participants (n=approximately 9 participants in a group). Swaziland was purposively selected, because the country has various NCM programmes; hence, it provided an opportunity to understand the various dimensions of NCM in practice. Swaziland is also the oldest Nazarene Church in Africa after the official establishment of the Church of the Nazarene in 1908. The church was started in 1910. The country has NCM as an NGO as well as a church-driven ministry. The country also represents a broad range of mature NCM ministries that currently include schools, hospitals, child sponsorship, water and sanitation hygiene (WASH), HIV awareness and treatment, and many other social projects. Swaziland thus provided useful information into the maturation of NCM. The collected data was analysed using a thematic approach.

5. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

5.1 Theological basis of compassionate ministry by NCM coordinators

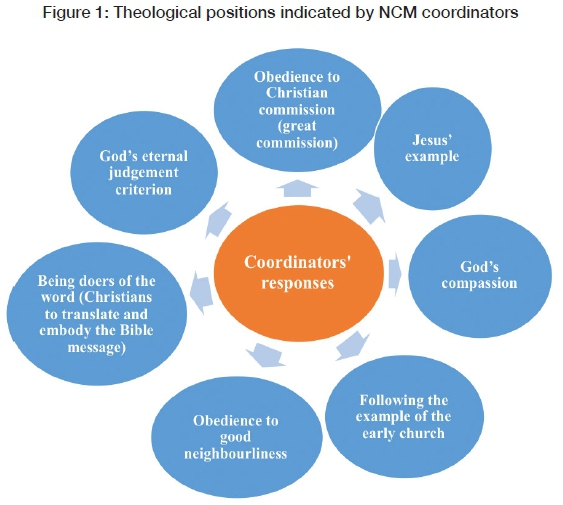

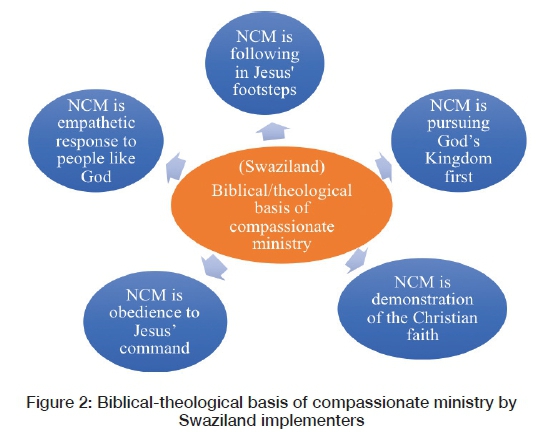

The thematic diagrams in Figures 1 and 2 indicate the theological positions presented by NCM coordinators and Swaziland implementers.

According to Figure 1, the coordinators identified seven compassionate ministry theological themes. Obedience to Jesus' commission was identified as a theological basis. Five participants made this point very clear. They argued that Jesus being Lord and Master of the church means that the church should "obey his commission. This commission is about preaching the word of his kingdom and heal the sick as he commanded in Matthew 10 and 28".1 Thus the church's compassionate ministry should be understood as an obligatory exercise for Christians that should be obeyed. Jesus' example was also pointed out as a model for doing compassionate ministry: "Jesus didn't only command Christians to preach the Kingdom of God message and practically demonstrate it (Matthew 10:8ff; 28:19-20), but also showed the way it should be done".2

While Jesus' example of doing holistic ministry provides a practical example of the basis of NCM, another model was God's compassion for humanity, which Christians should follow (Lk. 15; Mt. 9:36; Mk. 6:34): "The compassion of God is a model that should compel Christians to participate in holistic mission i.e. word and deed."3 The coordinators explained that "as seen in Luke 15, the Father (God) felt compassion for his son and compelled to act to embrace him so Christians should do the same".4 The example of the early church, as recorded in Acts, where the Christians practised compassionate care and practical ministry to address each other's needs, was also cited as another biblical-theological basis for compassionate ministry: "We follow the example of the early church as recorded in Acts 4"5. "The early church provides an example for the Church to participate in compassionate ministry".6 In caring for each other's needs, the church will be obedient to Jesus' command of "good neighbourliness" (Lk. 10:25-37).7

The coordinators also highlighted the fact that compassionate ministry entails "being doers of the word".8 This means that Christians should translate and embody the Bible message: "Christians should demonstrate Christ on earth and be an example of compassion as indicated in Bible message"9. God's reign and compassion entail justice, providing for people's needs, and it is the responsibility of the church to demonstrate these principles (Mic. 6:8; Jas. 1:27, 2:15). To emphasise the centrality of compassionate ministry within the life of Christians as key to God's mission to the world, the practical compassionate activities were cited as the criteria that God will use to judge Christians: "Compassionate activities are God's eternal judgement criteria (Mathew 25)".10

5.2 Theological basis of compassionate ministry by Swaziland NCM implementers

Figure 2 summarises the findings of the theological basis of compassionate ministry by Swaziland NCM implementers.

Compassionate work is done to follow in Jesus' footsteps and example: "Jesus ordered his followers to emulate his compassionate ministry example towards the needy and vulnerable in communities".11 Therefore, "the model shown by Jesus is not just adequate but it's simple for anyone to discern and follow (Matthew 25:35- 36)"12. By doing compassionate work,

Christians will be considering what the kingdom of God requires, namely to assist the needy and vulnerable people. Hence, compassionate ministry is about seeking God and his Kingdom first through caring for the needy using our resources (Mathew 6:19-21).13

Linking Christ's model and the importance of putting God first through practical acts of compassion, the respondents explained that compassionate acts are evidence of faith: "Faith without works is dead as recorded in the book of James. Faith is active. Action speaks louder than words."14 Furthermore, "Christians are urged to love their neighbours. From Jesus' teaching your neighbour is anyone requiring your help."15All people in need and vulnerable are our neighbours, as told by Jesus in the parable of the Good Samaritan (Lk. 10:25-37). Christian empathy was identified as a theological basis for compassionate ministry: "Christians should be empathetic to those who are in need because they are moved by the love of God to care for others."16

These theological justifications can be summarized into five categories. The first category relates to "Christian obedience to God's mission". This entails obeying God's commands to preach and demonstrate the Kingdom of God. Certainly, obeying God's commands is an important and justified expectation for Christians. However, the challenge with this theological basis is that the mission to be obeyed within the Church of the Nazarene does not seem to be well developed. Christian mission is assumed to be understood. The basic stated theological justification rests, to a large extent, on the fact that the Church of the Nazarene should obey the command to preach and do practical acts of compassion. Surely, without a thoroughly worked out and explicitly stated theology of God's mission that should be obeyed, the discussion remains superficial. Obedience is critical and so is identifying what should be obeyed. This suggests a challenge to have a well-developed theology of compassionate ministry.

The second category is following Jesus' example and paradigm of ministry. The example of Jesus as one who preached the Kingdom of God and practically performed acts that demonstrated the fullness of that Kingdom provides an example and model for Christians. The principle is that Jesus preached and healed; therefore, Christians should also preach and heal. At a superficial level, this principle seems to suffice; yet it has some weaknesses for compassionate ministry. A few aspects may suffice to illustrate the weaknesses. First, it seems to reflect a weak view of the Person and Work of Christ. In his earthly ministry, Jesus performed various acts of the Kingdom (preaching and healing), as he actively obeyed God the Father; yet there is also his passive obedience, as evidenced in his death on the cross. It thus appears that the theology does not reflect and apply Jesus' passive and active obedience.

Furthermore, there seems to be an uncritical position that the Church of the Nazarene Christians should do as Jesus did. This overlooks the reality of Jesus as God incarnate. Jesus was a divine human being. He was both truly God and truly human. This suggests that it may be unreasonable for Christians to uncritically argue that Christians should fully act like Jesus, considering human beings' limitations due to depravity. In addition, the silence on the other Persons of the Trinity (role of God the Father and the Holy Spirit) as linked to compassionate work seems to indicate a reductionistic understanding of Jesus' role on his mission as linked to the Father and the Holy Spirit. This may call for a clearer thinking on how Jesus' ministry should be properly understood and applied in the Christian interim period where the Holy Spirit (fully God) empowers and guides Christians as they partake in their compassionate ministry to the glory of the Father. A theological understanding of compassion should thus consider incorporating the paradox of Jesus as divine and human, and the consequent practical application of such a doctrine to compassionate work.

The third category entails Christians being people who embody God (in other words, Christian being). This is a way of demonstrating God to the world. Despite the importance of this thinking as a way of challenging Christians to aspire to higher compassionate ideals as seen in God, it runs the risk of making compassionate ministry a meaningless cliché. There are possibilities and limitations in this regard. For instance, how could ordinary Christians truly reflect and reveal the full heart of God considering human weaknesses due to depravity? The answer may lie in the possibility ushered by sanctification, while there is limitation through sinful tendencies (Rom. 7:15-19). The rhetoric that Christians should demonstrate the being of God needs to be interpreted and explained for practical relevance, otherwise it may remain an idea that does not practically convey a concrete message to Christians that can be implemented.

The fourth category entails following the early Church's example of compassion as recorded in the Bible. For example, Acts 4:33-34 indicates that, in the early church, people brought everything they had together at the apostles' feet and shared it with each other. As a result of these practical acts, there were no needy people among them. While the early church example rightly indicates that compassionate ministry can practically be done (possibility), it also suggests its challenges. As the early church was buzzing with compassion and care for one another, one couple Ananias and Sapphira (Acts 5:1-11) attempted to participate in care and compassion, but they sold their land and kept some of the money. They lied about their wholehearted commitment to share with others, which resulted in their death. Thus, the developments in the early church should be critically interpreted.

Read together, the stories not only clearly indicate a positive paradigm and practical possibility, but also show the reality of the challenge for people to do genuine compassionate ministry. Thus, a theology of compassionate ministry should present a balanced perspective that clearly indicates the challenges experienced, as Christians endeavour to do compassionate ministry for themselves and within the community (Rom. 7:19).

The fifth category is that compassionate ministry is a criterion of God's eternal judgement. As a way of encouraging compassionate involvement, the Church of the Nazarene seems to employ a "judgement threat" theology by focussing on eschatological judgement. Compassionate ministry becomes the criterion that God will use to judge Christians. This implies that, if you do not participate in compassionate acts, you are excluded from eternal life. Although this approach may coerce people to do compassionate acts, it undermines the doctrine of voluntary response to God's grace and the realised inauguration of the Kingdom of God. Compassion should be viewed as a response to God's gracious call, to which Christians are empowered by the Holy Spirit. This requires a balanced theology of compassion that focusses on the human being's will without coercion.

The above discussion considered a theological understanding of integral mission (compassionate ministry) driving NCM at institutional leadership and grassroots members. However, the following question provides insight: How is this NCM theology understood across the organisation from the top (leadership) to grassroots implementation levels in order to inform an institution-wide position?

5.3 Similarities and differences in understanding the theological basis between NCM coordinators and NCM implementers

The theological basis of compassionate ministry held by NCM coordinators (leaders) and implementing level staff (as represented by Swaziland NCM) are similar in some respects and different in others. A comparison of the similarities and differences are summarised in Table 1.

5.4 Similarities between NCM coordinators and implementing staff

Coordinators and implementing staff identified four similar theological ideas. First, the NCM workers viewed compassionate ministry as imperative, obeying Jesus' command to his mission of spreading the Kingdom of God in word and deed. Therefore, this compels them to do that which God urges them to do. The coordinators expressed a similar thought. They reasoned that compassionate ministry is an intertwined obligatory responsibility of preaching the word and demonstrating the Kingdom of God by doing practical acts as Jesus commanded. This means that compassionate ministry is a non-negotiable duty for Christians.

Secondly, they both stated that NCM is an expression of the Christian faith. The Swaziland workers indicated that NCM is a demonstration and practical exhibition of the Christian faith. It is a sign that shows the reality of being a Christian. This idea was equally expressed by the coordinators who mentioned that compassionate ministry entails being doers of the word. It is about Christians translating and embodying the Bible message. Compassionate ministry is about doing God's word. The responsibility does not only end in providing for people's needs, but also in striving for justice.

Thirdly, the coordinators and NCM workers similarly identified NCM as a way of following in Jesus' footsteps and his example. The NCM implementers described Jesus as a model and example whose footsteps should be followed. Jesus demonstrated how life should be lived in relation to needy people. Jesus also exemplified how Christians should conduct themselves. Similarly, the coordinators explained that Jesus provides an example of compassionate ministry and paradigm that should guide and be followed by Christians in compassionate ministry. He also exemplified how Christians should conduct themselves in perpetuity.

Fourthly, NCM was viewed as an empathetic response to other people, just as God is sympathetic and empathetic to all humankind in his identification with us in the incarnation and saving us from sin and its consequences. God's compassion indicates his empathetic attitude towards humanity. The implementing staff argued that compassionate ministry should be underlined by selfless sacrificial commitment to other human beings. Compassion leads to action to serve and meet other people's needs. If Christ did not die, humanity would have been doomed forever (Phil. 2:5-8). The coordinators added that compassionate ministry is about having the compassionate heartbeat of God. What moves God's heart should also move Christians. This implies that identifying with the compassionate God results in responding to the needs of the poor and disadvantaged in our communities and societies.

5.5 Differences between coordinators and implementers

The differences between coordinators and implementers were equally noted. The implementers pointed out an additional theological point, stating that NCM entails pursuing God's Kingdom first. Worshipping God or the Lordship of Christ are intertwined concepts that should be paramount in the lives of Christians. This should be evident through good works. Failure to do what is right (compassionate work) is tantamount to failing to invest in heaven, resulting in vanity or lack of profit in one's labour on earth. This suggests caution and warning worthy of consideration to ensure obedience and make God eminent and first in the lives of Christians.

The NCM coordinators, as predominant leaders of the Church of the Nazarene, identified the historical heritage of the denomination as a driving theological force. The coordinators argued that the Church of the Nazarene has tended to practise social holiness through compassionate ministry. The notion of social holiness suggests an approach where an individual who is a Christian is expected to be sensitive to the needs of society, especially the needy. NCM should draw from the DNA of the Church of the Nazarene. While the coordinators referred to the notion of social holiness in their theological justification, their use of the concept diverges somewhat from its meaning within Wesleyan theology. Pedlar ([s.a.]:1-2) explains that social holiness is not simply about social justice or practical acts of charity. Social holiness begins in a Christian community (church) and the church's internal interactions. The place of worship is where social holiness is cultivated, although it spills over to people outside the church. Social holiness relates to true salvation that translates into quality and effective Christian fellowship, which is a consequence of holy life. Christian koinonia is a means whereby the Holy Spirit forms the mind of Christ in Christians. Therefore, social holiness cannot be used exclusively or mainly to describe compassionate ministry only without including an equal emphasis on salvation and the interactive dynamics as a result of that salvation, as empowered by the Holy Spirit.

Further to the Nazarene denominational history that should inform NCM, the coordinators maintained that compassionate ministry is a way of following the example of the early church. The practices of the early church, as recorded in Acts, provide examples of holistic compassionate ministry and illustrate the possibility of practising compassionate care. It shows that it is not a theoretical concept, but a practically lived approach. The coordinators also indicated compassionate acts as a way of good neighbourliness. Jesus redefined neighbours by explaining that all those who require our help are our neighbours. The redefinition of the notion of neighbourliness challenges Christians to reconsider their duty to all human beings and to examine themselves regarding what they understand about being a good neighbour. Finally, the coordinators added that compassionate acts indicate God's eternal judgement criteria. Failure to care for the needy has negative consequences before God, while active involvement in ministering to the needy will be rewarded. Compassionate acts are not acts that are not recognised by God, but God's rewarding criteria.

5.6 Between broad and narrow concept

The theological positions expressed by the coordinators and implementing staff in Swaziland revealed agreement on the broad theological concept of compassionate ministry as both pivotal and critical denominational pillar. Obedience to Jesus' command and commission, demonstrating the Christian faith, being empathetic and following Jesus' example were the overarching shared theological positions. It seems obvious that the broad theological idea of compassionate ministry is shared within the organisation. However, at individual level, this understanding is nuanced and varies slightly. This is hardly surprising, considering that Theology, as an idea and concept, is informed and motivated by various aspects such as a person's reasons, preferences, experiences, motivations, backgrounds, levels of spirituality, theological tradition, history, and convictions. These underlying and driving motivations indicate that, while there could be commonality in terms of the broad theological idea of compassion, there is diversity at micro (individual) level. This suggests that an organisation should understand the notion of integral mission (compassionate ministry) within the institution in terms of unity in the broad theological understanding and diversity at individual level.

Institutional awareness of the reality of unity and diversity in understanding integral mission challenges those involved in integral mission ministries to create a common vision and understanding rather than assume that people hold a similar theology, position or conviction. This challenges ministry leaders to create a common vision built around the broad key theological agreements rather than to focus on different views and positions. It would be naïve for an institution to assume that all its members fully share in the theological principles and values of that organisation. People interpret and reinterpret what they view as their ministry obligations based on their experiences. This calls for consideration, vision-building, building a common framework, equipping, and discipleship in order to cultivate common theological understanding and position.

6. CONCLUSION

The article considered integral mission using the circumstances of the Church of the Nazarene's compassionate ministries. It sought to demonstrate that, despite the institution's position, there will be variations in the way in which individuals view integral mission. This challenges ministry leaders to create a common vision and develop a common theological position in order to drive the integral mission of the church.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andrews, D. [s.a.]. Integral mission, relief and development. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.daveandrews.com.au/articles/Integral%20M ission%20in%20Relief%20and%20Development.pdf (2017, 26 June). [ Links ]

Birdsall, K. & Kelly, K. 2005. Community responses to HIV/AIDS: An audit of AIDS-related activity in three South African communities. Johannesburg: Centre for AIDS Development Research & Evaluation. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 1991. Transforming mission. New York: Orbis. [ Links ]

Bowers, P. 2009. Christian intellectual responsibilities in modern Africa. Africa Journal of Evangelical Theology 28:91-114. [ Links ]

Chapman, J B. 1926. History of the Church of the Nazarene. Kansas City, MI: Nazarene Publishing House. [ Links ]

Chester, T. 2004. Good news to the poor: Social involvement and the Gospel. Nottingham: Intervarsity Press. [ Links ]

Church of The Nazarene Manual 2013-2017. 2013. History, constitution, government, ritual: Kansas City, MI: Nazarene Publishing House. [ Links ]

Crocker, G. & Juarez, H. (Eds) 1996. Missional church initiative transformational: Resources for compassionate ministries. Rhema: The Church's Faith in Action. [ Links ]

Foster, G. 2010. Faith untapped: Linking community-level and sectoral health and HIV/AIDS responses. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/195614.pdf (2017, 12 December). [ Links ]

Gilliland, D.S. 1998. Pauline theology and mission practice. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. [ Links ]

Ingersol, S. 1998. Ministering to the body as well as spirit: The transformation of Nazarene social ministry, 1925-1970. A presentation at the 4th Quadrennial NCM Conference Theological Symposium, Colorado Springs, 29 October 1998. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.google.co.za/search?dcr=0&source=hp &ei=XmLVWv2hApDaUoXrlpAB&q=Ministering+to+the+Body+as+ Well+as+Spirit%3A+The+Transformation+of+Nazarene+Social+Ministry%2C+1925-1970&oq=Ministering+to+the+Body+as+Well+as+Spirit%3A+The+Transformatio n+of+Nazarene+Social+Ministry%2C+1925-1970&gs_l =psy-ab.12...4792.4792.0.5970.1.1.0.0.0.0.686.686.5-1.1.0....0...1c.2.64.psy-ab..0.0.0....0.cpHlwT63Jis(2018, 17 April). [ Links ]

Kelly, K., Asta, R. & Stern, R. 2010. Community entry points: Opportunities and strategies for engaging community-supported HIV/AIDS prevention responses. Johannesburg: Centre for AIDS Development. [ Links ]

Langmead, R. 2012. Paradigm shifts in missiology: From Christendom to the missional church. Paper presented at Myanmar Institute of Theology. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://rosslangmead.50webs.com/rl/Downloads/Resources/MissionalChurchNov12.pdf (2018, 12 April). [ Links ]

Latz, D.B. [s.a.]. What is the church? Toward e Wesleyan Ecclesiology. [Online] Retrieved from: http://didache.nazarene.org/index.php/volume-6-2/6-gtiie-brower-latz/ file (2018, 5 March). [ Links ]

Magezi, V. 2007. HIV and AIDS, poverty and pastoral care and counselling: A home-based and congregational systems ministerial approach in Africa. Stellenbosch: Sun Media. [ Links ]

_____. 2012. From periphery to the centre: Towards repossessing churches for meaningful contribution on to public health care. HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 68(2), Art. #1312, 8 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v68i2.1312. [ Links ]

_____. 2017. Making community development at grassroots reality: Church-driven development approach in Zimbabwe's context of severe poverty. In die Skriflig 51(1), a2263. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v51i1.2263. [ Links ]

_____. 2018 Church-driven primary health care: Models for an integrated church and community primary health care in Africa (a case study of the Salvation Army in East Africa). HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 74(2), 4365. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i2.4365. [ Links ]

Mati, J.M. 2013. Bringing back 'Faith' in discourses of African civil society: Views from a convening in Nairobi. ISTR Africa Network Regional Conference, Nairobi, 11-13 July 2013 . [Online.] Retrieved from: http://cymcdn.com/sites/www.istr.org/resource/resmgr/africa2013/bringing _back_faith_in_disco.pdf [2017, 20 January]. [ Links ]

Mioah Network 2001. Integral mission. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.micahnetwork.org/integral-mission (2018, 10 April). [ Links ]

Monterroso, A. [s.a.]. Missions strategies: Compassionate ministries. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://home.snu.edu/~hculbert/alissa.pdf (2017, 14 July). [ Links ]

Mutowa, О. 2017. Nazarene Compassionate Ministries (NCM), Africa Region. [Online.]. Retrieved from: http://africanazarene.org/ncm/ (2017, 1 September). [ Links ]

Myers, B.L 2010. Holistic mission: New frontiers. In: B. Woolnough & W. Ma (eds), Holistic mission: God's plan for God's people (Oxford: Regnum Books International), pp. 119-127. [ Links ]

Nazarene Archives Inventories ND. Rescue the Perishing, Care for the Dying: Historical Sources and Documents on Compassionate Ministries. [Online] Retrieved from: http://nazarene.org/files/docs/rpcd1.pdf [2017, 14 July] [ Links ]

Nazarene Compassionate Ministries Magazine (NCMM) 2007. History of compassion in the Church of the Nazarene. NCM Magazine 4:2. [ Links ]

Padilla, CR. 2004. Holistic mission. Lausanne Occasional Paper No. 33. [ Links ]

Pedlar, J. [s.a.]. John Wesley and the mission of God, Part 5: Social holiness. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://jamespedlar.wordpress.com/2011/09/22/john-wesley-and-the-mission-of-god-part-5-social-holiness [2017, 4 August]. [ Links ]

Raser, H.E. 1998. Beating back the amnesia: Love for neighbor in the church of the Nazarene, 1975-1998. Nazarene Compassionate Ministries Conference, Theological Symposium, 29-30 October, Colorado Springs, Colorado. [ Links ]

Raistrick, Т. 2010. The local church, transforming community. In: B. Woolnough & W. Ma (eds), Holistic mission: God's plan for God's people (Oxford: Regnum Books International), pp. 138-148. [ Links ]

Samuel, V. 2002. Mission as transformation. Transformation 19(4):243-247. https://doi.org/10.1177/026537880201900404 [ Links ]

Samuel V. & Sugden, C. 2003.Transformational development: Current state of understanding and practice. Transformation 20(2):71 - 77. https://doi.org/10.1177/026537880302000203 [ Links ]

Smith, T.L. 1956. Revivalism and social reform: American Protestantism on the eve of the Civil War. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Stott, J.R.w. 1996. An historical introduction. In: J.R.W. Stott (ed.), Making Christ known: Historic mission documents from the Lausanne Movement 1974-1989 (Carlisle: Paternoster Press), pp.i - xxiv. [ Links ]

Sugden, C. 2010. Mission as transformation - Its journey among evangelicals since Lausanne 1. In: B. Woolnough & W. Ma (eds), Holistic mission: God's plan for God's people (Oxford: Regnum Books International), pp. 31-36. [ Links ]

Tiénou, Т. 1990. Indigenous African Christian theologies: The uphill road. International Bulletin of Missionary Research April:73-76. [ Links ]

Tizon, A. 2010. Precursors and tensions in holistic mission: An historical overview. In: B. Woolnough & W. Ma (eds), Holistic mission: God's plan for God's people (Oxford: Regnum Books International), pp. 61- 75. [ Links ]

Weekes, S.B. 2017. Situation analysis report of the church response to HIV and AIDS in Sierra Leone. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://pacanet.net/newsite/countries-where-we-work/sierra-leone-2/ (2017, 8 February). [ Links ]

Woolnough, В. 2010. Precursors and tensions in holistic mission: An historical overview. In: B. Woolnough & W. Ma (eds), Holistic mission: God's plan for God's people (Oxford: Regnum Books International), pp. 3-14. [ Links ]

Yates, D. 2003. Situational analysis of the church response to HIV/AIDS in Namibia: Final report. Pan African Christian AIDS Network. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://pacanet.net/newsite/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Namibia_Report1.pdf (2017, 8 February). [ Links ]

1 Interviews 6, 7, 13, 16, 17.

2 Interviews 1, 19, 24, 25, 27.

3 Interview 10.

4 Interviews 13, 15.

5 Interview 12.

6 Interviews 7, 21, 22.

7 Interview 20.

8 Interview 13.

9 Interview 24.

10 Interview 25.

11 FGD2, FGD3.

12 FGD3.

13 FGD1.

14 FGD4.

15 FGD1, FGD3, FGD6.

16 FGD2.s