Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.38 n.2 Bloemfontein 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v38i2.3

ARTICLE

Psalm 62: Prayer, accusation, declaration of innocence, self-motivation, sermon, or all of these?

Prof. P. J. Botha

Department of Ancient and Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Pretoria. E-mail: phil.botha@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Because of its seeming mix of different styles, Psalm 62 has intrigued researchers for a long time. It has been regarded by many as the prayer of an innocent person who was accused of some wrongdoing, but the direct exhortation to the "people" of God to put their trust in him seems to argue against this. The pertinent influence of wisdom-thinking also agitates against a reconstructed cultic setting. Some investigators have consequently argued that the psalm is a conflation from different sources. This article attempts to contribute to the debate about the seeming mix of styles by arguing from a social-scientific analysis that the psalm should be read against the background of a post-exilic context of exploitation in Jerusalem and the ensuing debate about the value of continued dedication to God.

Keywords: Psalm 62; Literary analysis; Social-scientific analysis; Wisdom influence ; Internal conflict

Trefwoorde: Psalm 62; Literêre analise; Sosial-wetenskaplike analise; Wysheidsinvloed; Interne konflik

1. INTRODUCTION

What type of psalm is Ps. 62, and what is it that its author or authors wanted to communicate? These questions have led to various proposals about its Gattung and a corresponding wide variety of interpretations. It has been argued that Ps. 62 is an individual psalm of trust or confidence (Kraus 1966:436, Anderson 1972:450);1 the prayer of a persecuted person (Weiser 1975 [1959]:446);2 a song of thanksgiving (Weber 2001:276);3 a composition only characterised by the forms and motifs of a psalm of trust (Hossfeld & Zenger 2002:373; Van der Ploeg 1973:365);4 or even a document setting out the dispute between a falsely accused person and his pursuers (Seybold 1996:244).5 The clear influence of wisdom has led scholars like Gunkel, Kraus, and others to put it in the wisdom tradition (Tate 1990:120),6 but Tate insists that it is only "near wisdom" and does not clearly belong to this rather "amorphous" category (Tate 1990:120).7 This array of opinions shows that investigators have in the past often embarked on their interpretation from the assumption that the psalm was used in some kind of ceremony, ritual, or procedure in the Temple (or a temple) and that this institutional context contains the key to its interpretation.8

In this article, the form and contents of Ps. 62 are used to ask what can be inferred about the social context in which it would have been useful and meaningful. What phenomena or actions were seen by the author or authors to be problematic and which remedies are proposed or advocated? If it were meant to be a prayer or a psalm of thanksgiving, it certainly deviates from what one would expect in those genres: Only in verse 13 is the "Lord" (אדני) addressed directly. Apart from that verse, the author addresses his enemies (v. 4), himself (vv. 6-8), and his compatriots (vv. 9-11). In the other verses, it is difficult to be sure whether the author speaks to Yahweh, to any of these persons, or to a priest or other functionary (vv. 2-3; 5). The purpose of the psalm rather seems to be offering advice to the "people" (עם v. 9) of the psalmist, while he uses his own commitment to, and trust in, God as an example to others (vv. 2-3). The psalmist also clearly speaks with the authority of a wisdom teacher in certain verses (vv. 9-12). It is thus possible that verses 2-3 and 5, as well as those verses in which the opponents are directly addressed, were also formulated primarily for the benefit of the in-group of the psalmist.

The text and contents of the psalm will first be analysed and afterwards a social-scientific investigation will be used in an attempt to determine more clearly how the author saw his social situation and what strategy he used to address this situation.9

2. TEXTUAL AND LITERARY ANALYSIS OF PS. 62

2.1 Notesonthetextand translation

3b לא־אמוט רבה: The verb מוט in the niph'al can mean to "be made to stagger or totter." With the negative particle and in the context of God's being the "rock"and the"fortress" ofthe psalmist,it seems that"I willnot bemovedgreatly"isavalidinterpretation.

4a The form רָצְּחו is understood asa po'el imperfect second person masculine plural of רצח where the expected cholem isshortened to qamets to express anuance ofintensity,10 thus"with murderous intent."

4bc There are two possible interpretations here, both equally possible. The derelict wall or rampart could resemble the attackers, so that they are "as dangerous as an overhanging wall." This is the view of the translators of the New English Translation (NET) and it is explained like this in the translators' notes and also made explicit in their translation. But since verse 5a refers to the "elevation" of the "man" being attacked, it is possible that he is being compared to a city on a hill which is besieged, with the attackers on the verge of pulling down the wall with its ramparts.11The siege instruments are "deception" and feigned friendliness.

10 Some translations treat בני־אדם and בני אישׁ as synonymous ("men" and "human beings"). Others make a distinction and consider בני־אדם to refer to people of "low estate" or "low degree" while the בני אישׁ are considered to be people of "high estate" or "high degree." The distinction is based on the antithetic parallel in Ps. 49:3, where בני אדם is chiastically linked to poor people (אביון) and בני אישׁ to rich people (עשׁיר).12But even in this verse some interpreters regard the expressions to be synonymous. In Ps. 62:10 it does not make that much difference whether they refer to two different classes of humans, since both express the insignificance of mankind. In view of the fact that the psalmist warns against the lure of "wealth" (חיל) in verse 11, it is perhaps better to translate them distinctively.

2.2 The structure and argumentative thrust of Ps. 62

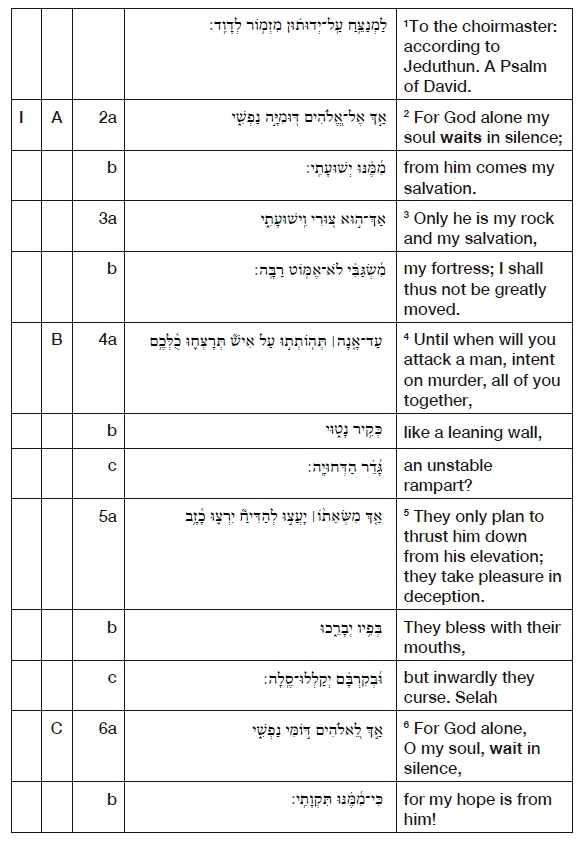

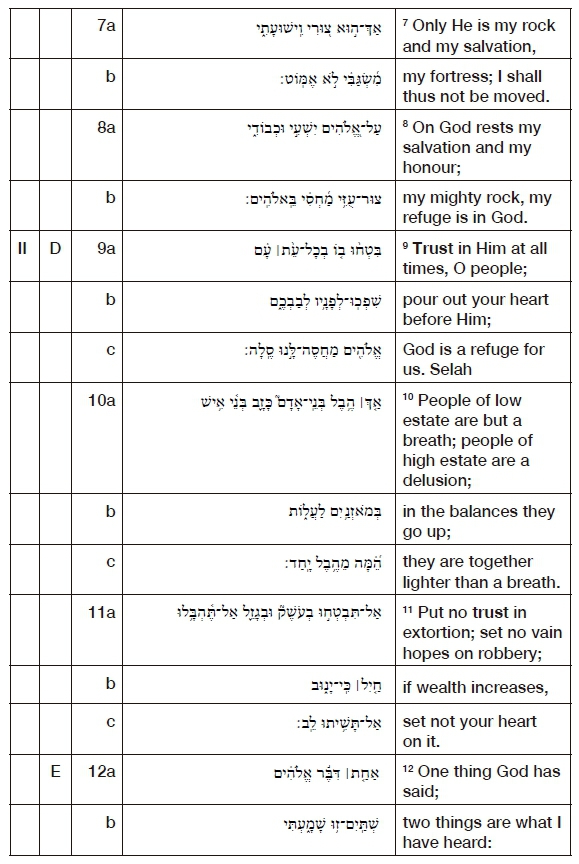

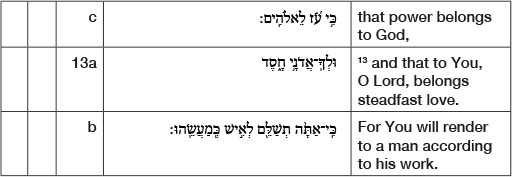

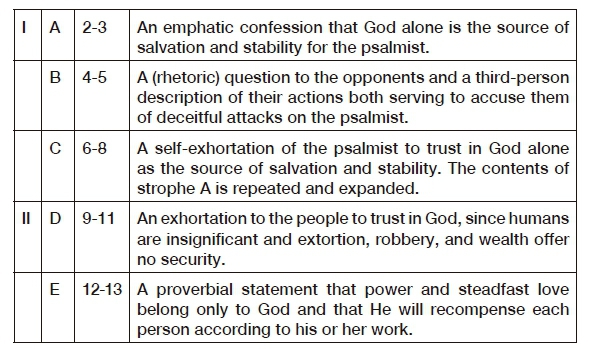

Ps. 62 can be summarised as follows:

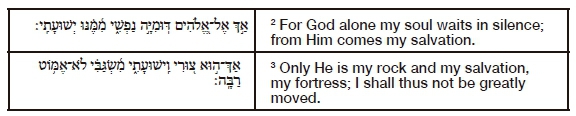

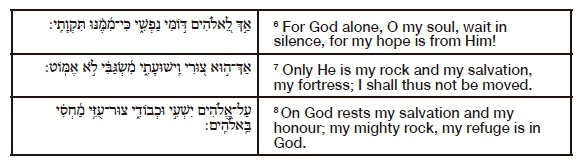

The argumentative quality of Ps. 62 is visible, inter alia, in the repetition of certain words. The most important of these repeated words is the "affirmative emphasizing particle"13 אך, "alone" or "only." It occurs six times, namely in verses 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 10, each time in an emphatic opening position.14 Some of these repetitions can be explained by the similarity between verses 2-3 and 6-8, which resemble a refrain. The differences between the two sections, however, point to an argumentative inclination:

The psalm can be split into two main parts: a self-exhortation in verses 2-8 and an exhortation in verses 9-13.15 Verses 2-3 (strophe A) has the form of a confession of trust in God who is the only source of salvation (note the repetition of ישׁועה) and protection (both "rock" and "fortress" are used as metaphors for this) who prevents the psalmist from being "moved" or "shaken." Verses 6-7, in contrast to this, begins as a self-exhortation and then returns to a confession in verse 8 (strophe C): The psalmist exhorts himself to "wait in silence" for God, since16He is a source of "hope" for the psalmist as well as for protection and salvation. Instead of "not greatly moved" (v. 3), the psalmist now insists that he will "not be moved" (v. 7), a statement which thus displays progression. Verse 8 completes the return to a confession and strengthens the previous confession by including a list of four things (in two concise synonymous parallels) provided by God: the "salvation" and "honour" of the psalmist rests on God while he also serves as a "mighty rock" and "refuge."

The ingenious variation in the use of prepositions describing the relationship with God enhances the effect of these pronouncements and of the repetition of אך, since it serves to emphasise the singular qualities of God as a source of salvation, protection, and stability17 (אל־אלהים, "for God," v. 2; ממנו, "from him," v. 2; לאלהים, "for God," v. 6; ממנו, "from him," v. 6; על־אלהים, "on God," v. 8; באלהים, "in God," v. 8).

In the context of strophes A and C in stanza I, the function of strophe B (vv. 4-5) becomes clearer. It serves to question the viability of the attacks of the opponents, since God is the guarantee of the psalmist's stability. It also serves to describe the intention and methods of the opponents, people who attack the psalmist in a treacherous way to force him out of "his position."18 In 2 Chron. 13:9, the same verb נדח in the hiph'il (cf. v. 5) is used to describe the removing of the Aaronite priests and Levites from the temple in order to replace them with immoral priests who obtained the priesthood with a bribe. This parallel use of the verb may be significant for the interpretation of the psalm.

The contents of strophes A and C also throw light on strophe D in stanza II, the exhortation to the "people" to "trust" in God at all times. This "trust" provides a summary of what the psalmist has confessed to do - and has exhorted himself to do - a short while ago, namely to regard God as the only "refuge" (מחסה, cf. the confession of the psalmist in v. 8b and the parallel exhortation to the people in v. 9c). The unacceptable alternative of trust in God is spelled out in strophe D, namely to trust in humans (vv. 9-10) or in wealth (v. 11). Whether these humans are of high or low standing does not matter, they are "a breath" (הבל) and "a delusion" (כזב) altogether (v. 10). These two words could also be translated as "vanity" and "a lie," but the imagery of the balance (v. 10bc) makes it clear that the psalmist is creating a pun to express the inconsistency of humans. The particle אך is also used at the beginning of verse 10 to create polarity between trust in God and trust in humans. Verse 11 criticises other presumed sources of stability, namely extortion, robbery, and wealth (whether obtained illegally or legally).

The most obvious meaning of strophe E is then also that trust in God alone is the only option for the psalmist and his group, since the confessed principle of retribution, together with the belief that only God has the power and steadfast love, will mean that those who use lies or deception (v. 5), extortion or robbery (v. 11) to obtain what they want, will be punished.

After this analysis of the argumentative coherence of Ps. 62, it is time to investigate its social dimensions.

3. A SOCIAL-CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF PS. 62

Ps. 62 is pseudonymously ascribed to "David," the king of Israel (v. 1). The reasons for this could be that the historical David was seen to be exemplary in his dedication to God, as well as an authoritative person. In 2 Sam. 22:3 (cf. Ps. 18:3), "David" confesses after all his battles that God is his "rock" (צור) in whom he takes "refuge" (חסה), the horn of his "salvation" (ישׁע), and his "stronghold" (משׂגב). Ps. 62:2-3 and 7- 8 are strongly reminiscent of this verse, since the words צור, ישׁועה, ישׁע and משׂגב occur in it.19 The "people" of the speaker are also advised later in the psalm to trust in God at all times, since he is a "refuge" (מחסה) to them (v. 9c; cf. non in 2 Sam. 22:3) as he also is to the psalmist (v. 8b).20 David, who had to wait a long time to become king of Israel after he had been divinely appointed to this position, also exemplified the ethos of Ps. 62:2 and 6 to "wait" for Yahweh to fulfil this expectation (cf. the "hope" of the psalmist, תקוה, in Ps 62:6). According to 1 Samuel, David twice had the opportunity to kill Saul, but would not do so out of respect for the fact that Saul was also God's anointed (1 Sam. 24 and 26). Because of this conflict with Saul, David complains that he was "driven out" (גרשׁ pi'el, 1 Sam. 26:19) from his share of the heritage of Yahweh, a motif echoed in Ps. 62:5, although a different expression is used (נדח hiph'il, to "force out"). David gave it over to Yahweh and trusted him to reward a man's righteousness (שׁיב לאישׁ את־צדקתו) and faithfulness (1) (את־אמנתו Sam. 26:23). This sentiment is also expressed (in different words) in Ps. 62:13 where the psalmist confirms that the Lord will "render to a man according to his work" (תשׁלם לאישׁ כמעשׂהו).

Like the historic David at the time when he was unjustly persecuted by Saul, the author of the psalm and members of the in-group needed "salvation" (ישׁועה, v. 3 and 7; cf. also ישׁע in v. 8). The author was in danger of being made to "move" (מוט niph'al, vv. 3 and 7). This looks like a metaphor from the motif of life as a journey ("stumble" or "totter"), but the aspect of instability in general and the disgrace that goes with it, may be more important in Ps. 62. In some contexts, the verb מוט in the niph'al has the meaning of "being removed," for example Prov. 10:30, where it forms antithesis to the concept of "staying in the land," thus signifying "being removed" from the land. This could be read in conjunction with the accusation against the opponents in verse 5 that they plan to "thrust" or "force out" (נדח, hi) the psalmist from his "elevated position" or "dignity" (שׂאת, verse 5).21 The word "honour" (כבוד) is also used to describe the threat against the psalmist (v. 8). The word "rock" (צור) is used three times in the psalm as a metaphor for the stability that God provides to the psalmist. In two of these instances, God's role as "rock" is mentioned precisely in connection with the possible "movement" of the psalmist (vv. 3 and 7). It thus definitely seems that the psalmist's position of honour was threatened by his opponents and that he pinned his hope on God to provide the support that he needed. His opponents were, however, not openly attacking him. Their secret "planning" (יעץ, v. 5) to topple him made them more dangerous. They were intent on "murder" (v. 4), but are (probably) compared in the psalm to enemies attacking a "leaning wall" and an "unstable rampart" (v. 4). In the next verse (v. 5), the psalmist refers to the treacherous modus operandi of his opponents. They "take delight in deception" (ירצו כזב) and pretend to bless people (probably the psalmist and his in-group), but inwardly they are actually cursing.

The treacherous attacks of opponents who are attempting to cause the downfall of the psalmist are therefore a major cause of concern for him. But among the in-group, there also were worrying trends. The psalmist uses himself as an example in his attempt to encourage the in-group to trust (בטח) in God alone (cf. the repetition of מחסה in vv. 8 and 9: "my refuge is in God"; "God is a refuge for us"). The adverbial extension of the exhortation to trust in God "at all times" (בכל־עת) in verse 9 is proof of the extent of the problem. Like Hannah at the temple in Shiloh, the in-group is encouraged to "pour out" (שׁפך) their "heart" before God, because He is a refuge for them (v. 9).22

In contrast to God, who can be trusted at all times, the psalmist emphasises the fickleness of human beings. They are like a mere breath, disappearing immediately. The author probably had the vapour accompanying breath on a cold day in mind, vapour which disappears almost immediately. The in-group is also warned explicitly not to trust (אל־תבטחו) in "extortion," "robbery", or "wealth" (v. 11). While the "hope" (תקוה) of the psalmist is "from God" (v. 6), the in-group should not "put vain hopes" (אל־תהבל) on illicit wealth (v. 11). The root of the word for "vanity" or "breath" (הבל) is also used as a verb (הבל) in the expression to not "put confidence in vanity" in verse 11, creating figura etymologica and establishing a close connection between frail humanity and inconsistent wealth acquired through criminality. The conclusion of the psalm, stating that "power" (עז) and "steadfast love" (חסד) belong to God alone and that He will retribute each person according to "his work," suggests that not everybody in the in-group would have accepted these statements as truths. It was probably necessary to reconfirm them. This may also be the reason why the psalmist emphasises his own "silence" (דומיה, v. 2; דומי, v. 6) before God. There were those who openly criticized God, and they had to be reminded that it is better to wait silently for God to act.23 The way the author or editors saw fit to do it, was to have "David" express these beliefs in the form of a wisdom aphorism.

The strategy of the author or editors therefore was to use a monologue by "David" in which he expresses a confession of faith (vv. 2-3); then to accuse the opponents in a fictive dialogue (vv. 4-5) before having David address himself in a self-exhortation which again becomes a confession (vv. 6-8). After that, "David" directs his attention to his "people" (v. 9), revealing the purpose of the earlier part of the psalm, namely to exhort the in-group to trust only in God, not in people (whether rich or poor) or wealth (whether acquired legally or through illicit means, vv. 9-11). The psalmist ends by quoting a wisdom aphorism (v. 12) before finally addressing the "Lord" himself in an affirmation of the doctrine of retribution (v. 13).24

Repetition of key words and particles which serve to stress certain ideas enhance the argumentative impact of the psalm. It is clear that the psalm is not simply the prayer of a persecuted person, but an explicit exhortation embedded in a self-motivating and accusing monologue. It is also not a legal document, but an ideological document, addressing a situation where members of the people of God, the "in-group," came under attack from people within the community who had power and wealth. The psalm makes an appeal to the in-group not to be fooled by the lure of either power or wealth, but to remain true to the values shared by God's people and therefore ultimately faithful to God himself. True power belonged only to God (v. 12).

4. A NOTE ON THE POSSIBLE TIME OF COMPOSITION OF PS. 62

Terrien (2003:460) says that the date of Ps. 62 is uncertain, but that it could come from early postexilic Judaism.25 Tate (1990:122) remarks that the circumstances of the psalmist seem to point to a time which was characterised by extortion, plunder, robbery, and an increase in the wealth of some people. Hossfeld and Zenger (2007:182) infer from the strong wisdom influence and the social context of verse 11 that the psalm probably originated in the milieu of "school wisdom." It should be noted, though, that they regard verses 9-13 as a later expansion of the "base psalm" found (in their view) in verses 2-8, and that the wisdom stamp would stem from the later reworking (2007:182). Weber (2001:278) notes the similarity of the heading of Ps. 62 with that of Ps. 39, as well as the similarity of motifs, the wisdom influence in both, and specific words that are used in Pss 39 and 62.26 This is indeed the case: Ps. 39:12c (אך־הבל כל אדם) could have been a source for Ps. 62:10a (אך־הבל בני אדם), or it could be inferred that Ps. 62 alludes to Ps. 39.27 In Ps. 39, the affirmative emphasizing particle אך ("surely, only") is also used four times28 and this feature establishes a close connection between these two psalms as well as with Ps. 73 were the same particle is used three times.29 The use of this particle throughout Ps. 62, a particle which also plays a role in other wisdom compositions, some of which address the problem of retribution (for example Pss 37:8-9 and 49:16), mitigates against the argument that Ps. 62 consisted of a base psalm of confidence which was later expanded.30 This does not seem to be so evident.

In view of its consistent argumentative inclination and the strong influence of wisdom, Ps. 62 probably originated as a whole in the Persian or Hellenistic period.31 It seems that the power and wealth which some Jews enjoyed, while many others possibly suffered deprivation,32 became a temptation for some members of the in-group to abandon their trust in God and to make use of unlawful methods or to set their whole heart on acquiring or increasing wealth and power. The author of the psalm possibly was a prominent member of the community who suffered as a result of the enmity of unscrupulous peers.33 His greatest concern, though, was to exhort and encourage members of the in-group to stay true to the values and faith of the true people of God, since he was absolutely convinced that this was the only way to achieve true inner peace and stability.

5. CONCLUSION

Ps. 62 is an ideological text with prominent argumentative features from beginning to end. It is pseudonymously presented as a psalm of David who thus serves as an example for the contemporaries of the editors, but also as a figure of authority who could exhort the Israelites since God had helped him to triumph over all his opponents. For the greater part, it is a self-deliberation in which the psalmist confirms his conviction that help can only come from God and that he therefore must wait faithfully and confidently for God to intervene on his behalf against opponents who wanted him out of the way. In a fictive direct address to these enemies, he accuses them of trying to kill him socially. 34 The psalmist then turns to his "people," exhorting them to trust in God alone and to guard against putting their hopes on human power, whether these humans were of high or low standing, or on wealth, whether acquired through criminality or rightfully. It ends with a numerical saying which confirms that power and steadfast love belongs to God alone and that He would punish the evildoers and bless the righteous.

In view of its consistent argumentative thrust and its connections to wisdom, the psalm should be understood as a unitary composition which originated in the post-exilic period at a time when foreign rulership, economic hardship, and fierce competition for power and influence enticed some members of the in-group to abandon their faith in Yahweh and to clutch influence and wealth in ways which clashed directly with the ethos of Jewish faith.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, A.A. 1972. The Book of Psalms. Volume I: Psalms 1-72. The New Century Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Bland, D. 1974. Exegesis of Psalm 62. Restoration Quarterly 17:82-95. [ Links ]

Bremer, J. 2016. Wo Gott sich auf die Armen einlässt. Der sozio-ökonomische Hintergrund der achämenidischen Provinz Jehud und seine Implikationen für die Armentheologie des Psalters. Bonner Biblische Beiträge 174. Göttingen: V&R Unipress. [ Links ]

Charney, D.H. 2015. Persuading God: Rhetorical Studies of First-Person Psalms. Hebrew Bible Monographs, 73. Sheffield: Phoenix Press. [ Links ]

Elliott, J.H. 1993. What is Social-Scientific Criticism? Minneapolis: Fortress. [ Links ]

Hossfeld F.-L. & Zenger, E. 2002. Die Psalmen II: Psalm 51-100. NEB. Würzburg: Echter Verlag. 2007. Psalmen 51-100. Übersetzt und ausgelegt. HTKAT. Freiburg: Herder. [ Links ]

Joüon, P. & Muraoka, T. 2006. A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew. Second edition, Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute. [ Links ]

Koehler, L. & Baumgartner, W. 1994-2000. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (HALOT). Electronic version. Revised by W. Baumgartner and J.J. Stamm with assistance from B. Hartmann, Z. Ben-Hayyim, E.Y. Kutscher & Reymond, P. Translated and edited under the supervision of M.E.J. Richardson. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. [ Links ]

Kraus, H.-J. 1966. Psalmen. 1. Teilband. BKAT 15/1. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener. [ Links ]

Seybold, K. 1996. Die Psalmen. Handbuch zum Alten Testament I/15. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr. [ Links ]

Tate, M.E. 1990. Psalms 51-100. WBC. Dallas: Word Books. [ Links ]

Terrien, S. 2003. The Psalms. Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary. The Eerdmans Critical Commentary. Grand Rapids / Cambridge, U.K.: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Van Der Ploeg, J.P.M. 1973. Psalmen. Deel 1. Psalm 1 t/m 75. De Boeken van het Oude Testament. Roermond: J.J. Romen & Zonen. [ Links ]

Weber, B. 1992. "Ps 62:12-13: Kolometrie, Zahlenspruch und Gotteswort." Biblische Notizen 65:44-48. 2001. Werkbuch Psalmen I. Die Psalmen 1 Bis 72. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. 2016. "'Es gibt keine Rettung für ihn bei Gott!' (Psalm 3:3)." In: A. Ruwe (ed.), Du aber bist es, ein Mensch meinesgleichen (Psalm 55:14). Ein Gespräch über Psalm 55 und seine Parallelen (Neukirchener Theologie; Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener), pp. 191-267. [ Links ]

Weiser, A. 1962. The Psalms: A Commentary. Old Testament Library. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Wilson, G.H. 2002. Psalms Volume I. New International Version Application Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Zenger, E. 1990. "'Gib mir Antwort, Gott meiner Gerechtigkeit' (Ps 4,2). Zur Theologie des 4. Psalms." In: J. Zmijewski (ed.), Die alttestamentliche Botschaft als Wegweisung: Festschrift für Heinz Reinelt (Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk), pp. 377-403. [ Links ]

1 Kraus says with great conviction that it belongs to the Gattung of the "individuellen Vertrauenslieder," but adds that these are related to individual laments and supplications. Bland (1974:82) describes it, together with Pss 4, 16, 27, and 131, as a "psalm of trust."

2 According to Weiser, the psalmist has been forsaken and is now persecuted by his former friends who still pretend to be his friends but are full of hatred and seek his life.

3 Weber says that the psalm is "gattungsmässig komplex." It reminds of a lament, but without the expected supplication and with two confessions of trust framing the accusation against the enemy. These characteristics, combined with the "wisdom-generalising expansion" (my translation of the German) leads him to think of the context of a Toda, a song to accompany a sacrifice of thanksgiving.

4 According to Van der Ploeg, it is a prayer in which the psalmist lifts his spirit up to God in whom he finds rest, and (a prayer) in which he exhorts others to put their trust in God.

5 According to Seybold, the accused sought asylum in the temple since he asserted in turn that the accusations were false and based on lies. The text was only secondarily turned into a prayer-like and meditative psalm through repetition of the declaration found in vv. 2-3 in vv. 6-7 so as to form a refrain; and also through the introduction of a plea in the concluding verse. Terrien (2002:459) in turn says that the psalm does not strictly belong to the category of prayers of vigil, but was partly inspired by the legal genre of supplication and was composed for use during "the nocturnal ordeal of temple asylum."

6 Hossfeld & Zenger (2007:179) regard it with Gunkel as a unique composition, characterized by the forms and motifs of a psalm of trust, but from verse 9 onwards particularly influenced by wisdom forms and thinking. Gunkel's description is given in Gunkel (1986:262-3).

7 Tate, like Seybold, thinks that the speaker is someone who has taken refuge in a sanctuary because he or she was assaulted (verbally or physically) and hopes for a Heilsorakel to set him or her free.

8 This kind of approach is now outdated. Hossfeld & Zenger (2007:181) say the idea that the psalm was conceived and used as a formulary for an asylum seeker should be regarded with scepticism. Although such a situation may be reflected in the metaphors of protection and refuge in the psalm, this metaphoric complex is only one aspect of a mixture of metaphors. They also think the psalm was not meant for a single situation, but rather an overall interpretation of the "condition humaine." This statement is possibly too general. It does seem that more can be inferred about the situation for which it was composed.

9 Cf. Elliott (1993:72). The aim of this type of analysis as part of the exegetical enterprise, is "the analysis, synthesis, and interpretation of the social as well as the literary and ideological (theological) dimensions of a text ... and the manner in which it was designed as a persuasive vehicle of communication and social interaction, and thus an instrument of social as well as literary and theological consequence."

10 Cf. Joüon-Muraoka's (2006 electronic version) note in §59, where this form in Ps. 62:4 is described as a po'el ("despite the dagesh in the a") with such purpose.

11 Weber (2016:226) defends this position.

12 Cf. the entry in HALOT (Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament) s.v. אישׁ, entry 449 no. 3: בְּנֵי ִאישׁ "the distinguished people Ps. 4:3; 49:3." Koehler & Baumgartner (1994-2000).

13 This is the description in Koehler & Baumgartner (HALOT, par. 464).

14 Charney (2015:50 calls the "sound pattern of the verse - initial Hebrew words" the "most potent persuasive device in Psalm 62."

15 Cf. the strong assertion of Hossfeld & Zenger (2007:181-2) who demarcate these two sections, against Tate and Mays who segment vv. 2-5; 6-11; and 12-13. Weber (1992:44) originally demarcated three stanzas in accordance with the Sela's: 2-5; 6-9; 10-13. He later changed this to two stanzas consisting of verses 2-8 and 9-13 (Weber 2001:275-276).

16 The particle כי is used four times in the psalm, but only in v. 6 and v. 13 is it used causal. These two instances also demonstrate an argumentative intent, though.

17 Also note the repetition of the emphatic phrase אך־הוא in vv. 3 and 7.

18 While she recognises the argumentative thrust of Ps. 62, (Charney 2015:48) thinks that the attacks are not aimed at the speaker in Ps. 62, but rather an unnamed third party. She says that "a man" (אישׁ) in v. 4 probably does not refer to the speaker. Within the context of strophes A and C, where the suppliant speaks of waiting for God for "salvation," it seems more probable that the impersonal reference to "a man" in v. 4 and the third-person reference to "him" in v. 5 both refer to attacks on the speaker himself.

19 In Ps. 62:9, ישׁועה is changed to ישׁ

20 Cf. also the similarities between 2 Sam. 22:47 and 51 and Ps. 62:3 and 13.

21 Cf. the use of this word in Gen. 49:3 for the "exaltation" or "dignity" of the tribe of Reuben: "Reuben ... preeminent in dignity (יתר שׂאת) and preeminent in power."

22 Hannah is described as a woman "troubled in spirit" (קשׁת רוח) who "poured out" (שׁפך) her "soul (נפשׁ)" before Yahweh in 1 Sam. 1:13. This form of the expression is also used in Lam. 2:19 (with שׁפך and לב).

23 Cf. the similarity between Ps. 62 and some of the other psalms where the verb דמם also occurs. In Ps. 4: the rhetorical question about how long the attacks on the psalmist will carry on (4:3 ,עד־מה); the reference to "men of rank" (בני־אישׁ 4:3), and the advice to think things over and keep silent (4:5). In Ps. 37: The advice to be still before Yahweh and wait patiently for him (37:7). In Ps. 131: The confession of the psalmist that he had calmed and quieted his soul (131:2) and the advice to "hope" in Yahweh (131:3). Cf. also the very useful analysis of the meaning of דומיה and דמם in Ps. 62 by Bland (1974:85-86).

24 Hossfeld & Zenger (2007:180) list the following wisdom forms: v. 9: admonishment; v. 10: truth saying; v. 11: warning; vv. 12-13: numbers saying. These verses are also characterized by wisdom techniques such as black-white technique; anthropologizing generalisation in v. 10; the temporality metaphor of הבל (v. 10); warning against attaching wrong values to riches and power (v. 11); the doctrine of retribution (v. 13).

25 He understands the psalm as having been "partly inspired by the legal genre of supplication to be used for the nocturnal ordeal of temple asylum" (2003:459).

26 He mentions the motifs of "keeping silent" (39:3, 10; 62:2, 6) and "vanity" (62:10 ;12 ,7 ,39:6 הבל [x2], 11).

27 The saying seems to fit the immediate context in Ps. 39:6 slightly better as part of the whole argument in the psalm, but it also makes perfect sense in Ps. 62:10.

28 Ps. 39:6, 7 (x2), 12.

29 Ps. 73:1, 13, 18.

30 Cf. the thematic parallels of Ps. 62:5 and 11 with Ps. 49:5-6; compare also Ps. 62:10 with Ps. 49:12.

31 Its time of origin must have been in the late Persian or early Hellenistic period, since the wisdom forms have developed from those found in Proverbs. Hossfeld & Zenger (2007:181) point out that the numbers saying used at the end is a wisdom form par excellence, but that it no longer lists daily human experiences (such as those found in Proverbs), but faith experiences which cannot be verified, but only accessed by those who risk stepping into a relationship of trust.

32 The whole Persian period proved to be financially challenging for some Jews. One must reckon with unfavourable agricultural phenomena, the stress caused by those who returned from exile and asserted historical rights to land their families once owned, the inability of many existence farmers to provide for their families on land holdings which became too small, and the requirement of the Persian rulers that taxes be paid with money instead of produce. For a general description of the social and economic situation, cf. Zenger (1990:396-400). See also the detailed analysis of the socio-economic situation of the Persian Period in Judah by Bremer (2016). Ps. 62 is not one of the "psalms of the poor," but probably also originated, together with other psalms from the Second Davidic Psalter, in the circle of the "servants of Yahweh." For the connection they had with the poor, cf. Bremer (2016:436-7).

33 Hossfeld & Zenger (2007:182) say that the situation seems to have been such that the author ostensibly lived in peace with his enemies, but that those people had enough power and influence to make life difficult for him.

34 Wilson (2002:879) also interprets the attack of the enemies as "less physical and more verbal."