Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.38 suppl.26 Bloemfontein 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup26.4

ARTICLES

The  in Joshua 6 and 7, influenced by P?

in Joshua 6 and 7, influenced by P?

E.E. Meyer

University of Pretoria, South Africa. E-mail: sias.meyer@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The article engages with the old question of Priestly influence in the book of Joshua and is, to a large extent, a response to Dozeman's most recent commentary on Joshua 1-12. The article focusses specifically on the and argues that there are more intertextual links between the understanding of in Joshua 6 and 7 and texts from Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets than with Priestly texts.

Keywords: Ban, Priestly text (P), Joshua, Deuteronomy, Sacrifice

Trefwoorde: Banvloek, Priesterlike teks (P), Josua, Deuteronomium, Offer

1. INTRODUCTION

This article addresses a very old question, namely whether there is any evidence of P or Priestly influence in chapters 6 and 7 of the Book of Joshua. In Dozeman's (2015) recent commentary, the answer to the question is a clear "yes". His argument has many facets to it, one of which will be the focus of this article, namely the meaning of  in Joshua 6 and 7. In his argument, "P" is used rather loosely.1In this article, a brief overview of the occurrence of the root

in Joshua 6 and 7. In his argument, "P" is used rather loosely.1In this article, a brief overview of the occurrence of the root  is followed by a summary of Dozeman's position on how the understanding of

is followed by a summary of Dozeman's position on how the understanding of  in Joshua 6 and 7 has been influenced by Priestly understandings of the term. This leads to the larger and rather complicated debate on making sense of

in Joshua 6 and 7 has been influenced by Priestly understandings of the term. This leads to the larger and rather complicated debate on making sense of  , in which I will draw on older (Brekelmans) and more recent (Versluis; De Prenter) studies of

, in which I will draw on older (Brekelmans) and more recent (Versluis; De Prenter) studies of  . I will also address two other issues, namely whether (the non-Priestly)

. I will also address two other issues, namely whether (the non-Priestly)  could be regarded as a sacrifice and the problem of the two opposite meanings of

could be regarded as a sacrifice and the problem of the two opposite meanings of  . I will also examine other texts from Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets, but not all occurrences of the term.2 Ultimately, I will argue that Dozeman is (mostly) wrong about

. I will also examine other texts from Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets, but not all occurrences of the term.2 Ultimately, I will argue that Dozeman is (mostly) wrong about  in Joshua 6 and 7 being influenced by Priestly ideas.

in Joshua 6 and 7 being influenced by Priestly ideas.

In the book of Joshua, there is a difference between the distribution of the noun and the verb. The noun, which has traditionally been translated as "ban",3 occurs thirteen times in the book, with twelve of these in chapters 6 and 7, and is thus clearly concentrated in these chapters.4 In one instance (22:20) where the noun is found outside of these two chapters, it actually refers back to the story of Achan in chapter 7. The verb is found only in chapter 6 and not in chapter 7; however, it is more prevalent in chapters 10 and 11.5 It is always in the Hiphil.

2. AS A COMBINATION OF P AND D

Dozeman (2015:54-69) argues that the  in the Book of Joshua is a mixture of

in the Book of Joshua is a mixture of  from Deuteronomy and

from Deuteronomy and  from Priestly texts.6

from Priestly texts.6

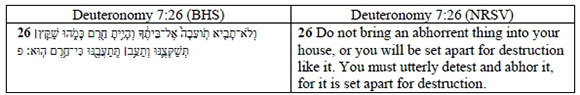

Drawing on the work of Stern (1991:89-122) and Weinfeld (1972a), Dozeman (2015:56-57) presents Deuteronomy's understanding of the ban by referring to texts such as Deuteronomy 7:2 and 26, and 13:18. In Deuteronomy,  is war booty, which, according to Dozeman, is equivalent to

is war booty, which, according to Dozeman, is equivalent to  or abhorrent. Yet it is argued that

or abhorrent. Yet it is argued that  itself does not have the power to contaminate, but the "power of the devoted object to contaminate" lies with the "desire of the people" and not within the object itself.

itself does not have the power to contaminate, but the "power of the devoted object to contaminate" lies with the "desire of the people" and not within the object itself.

It appears that Dozeman for gets to mention that the previousverse does, infact,refer tothe "images of their gods"( ) and thesilverand gold on them which are supposed to be burned. This gold and silver can ensnare (Nifal of

) and thesilverand gold on them which are supposed to be burned. This gold and silver can ensnare (Nifal of  ) the addressee. Otto (2012:880) argues that

) the addressee. Otto (2012:880) argues that  "dient im Deuteronomium zur Bezeichnung kultischer und ethischer Abgrenzung".7 It seems that the thing associated with the other gods and the act of bringing that into one's house, the act of crossing the boundary, is abhorrent. This is the only instance where

"dient im Deuteronomium zur Bezeichnung kultischer und ethischer Abgrenzung".7 It seems that the thing associated with the other gods and the act of bringing that into one's house, the act of crossing the boundary, is abhorrent. This is the only instance where  and

and  are used in the same verse. It is not clear to me that what is

are used in the same verse. It is not clear to me that what is  is, by definition,

is, by definition,  The two words are also used in close proximity in Deuteronomy 13 (vv. 15, 16), where it is even clearer that

The two words are also used in close proximity in Deuteronomy 13 (vv. 15, 16), where it is even clearer that  refers to worshipping other gods and the

refers to worshipping other gods and the  mentioned in verse 16 is the result of that, or more accurately the response to that. It appears that it is appropriate to turn something that is

mentioned in verse 16 is the result of that, or more accurately the response to that. It appears that it is appropriate to turn something that is  into

into  or to treat it as

or to treat it as  In addition, it is clear to Dozeman (2015:57) that, in texts such as Deuteronomy 7:26 and 13:18, there is an element of "religious exclusion", since these texts encourage a negative "attitude toward the indigenous nations"; he seems to be right in this regard. Furthermore, Dozeman (2015:57) argues that,

In addition, it is clear to Dozeman (2015:57) that, in texts such as Deuteronomy 7:26 and 13:18, there is an element of "religious exclusion", since these texts encourage a negative "attitude toward the indigenous nations"; he seems to be right in this regard. Furthermore, Dozeman (2015:57) argues that,

[e]ven though the ban is a divine command, its execution is not a sacred action, nor do people under the ban belong to the Deity, making their deaths sacrifices to Yahweh.

This is thus his understanding of the  in the book of Deuteronomy. According to Dozeman,

in the book of Deuteronomy. According to Dozeman,  semantically belongs to an opposite domain to Yahweh; it is

semantically belongs to an opposite domain to Yahweh; it is  and may, therefore, not be brought into the camp. It is unholy or profane, and Dozeman is clear that it is not a sacrifice. We will no enter the larger debate on the meaning of

and may, therefore, not be brought into the camp. It is unholy or profane, and Dozeman is clear that it is not a sacrifice. We will no enter the larger debate on the meaning of

3. THE MEANING OF

Traditionally, scholars have distinguished between a war  and a peace

and a peace  Stern's (1991) book is a good example of this. Most of the examples of

Stern's (1991) book is a good example of this. Most of the examples of  in the Hebrew Bible are of the war

in the Hebrew Bible are of the war  including the ones in Deuteronomy, as mentioned by Dozeman. The examples of peace

including the ones in Deuteronomy, as mentioned by Dozeman. The examples of peace  discussed by Stern (1991:125-135), for instance, are the ones Dozeman attributes to P and calls the "cultic"

discussed by Stern (1991:125-135), for instance, are the ones Dozeman attributes to P and calls the "cultic"  Stern (1991:125-126) understands this development into the peace

Stern (1991:125-126) understands this development into the peace  as follows:

as follows:

In the writings of the priests (including Ezekiel) we find the

in a peaceful, cultic setting, nestling amid the minutiae of the cultic regulations. The

has been somewhat "civilianized," and it has been reduced to a technical term among other technical terms. ... The

still reflects its etymology as a form of separation, inviolability, and holiness. The element of destruction is still present.

Earlier scholars such as Brekelmans (1959:163-170) and Lohfink (1982:207-209) also made this distinction.8 For Brekelmans (1959:47-48), the original form of  was a noun expressing a characteristic ("een eigenschap") which he calls a "nomen qualitatis". It only later developed into a "nomen concretum", a noun describing the thing that takes on the characteristic. The verb later develops from these meanings and simply describes how something becomes

was a noun expressing a characteristic ("een eigenschap") which he calls a "nomen qualitatis". It only later developed into a "nomen concretum", a noun describing the thing that takes on the characteristic. The verb later develops from these meanings and simply describes how something becomes  . According to Brekelmans (1959:52), there are at least three different meanings under the broader umbrella of the war

. According to Brekelmans (1959:52), there are at least three different meanings under the broader umbrella of the war  of which the oldest one has a "religious" meaning.9

of which the oldest one has a "religious" meaning.9

For Dozeman, the  in Priestly literature is vastly different from the

in Priestly literature is vastly different from the  in Deuteronomy. Allegedly, in Deuteronomy,

in Deuteronomy. Allegedly, in Deuteronomy,  is unholy or profane, or

is unholy or profane, or  In Priestly literature, the meaning of

In Priestly literature, the meaning of  tends to go the other way, namely closer to holiness itself. Dozeman (2015:57) starts by referring to Ezekiel 44:29 and Leviticus 27:21, 28 and 29.10 It is clear to him that, in these instances,

tends to go the other way, namely closer to holiness itself. Dozeman (2015:57) starts by referring to Ezekiel 44:29 and Leviticus 27:21, 28 and 29.10 It is clear to him that, in these instances,  is a case of sacrifice. The five instances of

is a case of sacrifice. The five instances of  in Leviticus 27 also show that

in Leviticus 27 also show that  now becomes something that belongs to Yahweh and is most holy (

now becomes something that belongs to Yahweh and is most holy ( ). Something is transferred from the profane to the sacred world by means of a sacrifice.

). Something is transferred from the profane to the sacred world by means of a sacrifice.

The Priestly teaching of the ban is thoroughly grounded in cultic language, in which people or objects under the ban are transferred to the realm of the Deity, designated by the phrase "to Yahweh" (Dozeman 2015:57).

One should thus note that, for Dozeman, the  in Deuteronomy does not belong to YHWH, unlike the

in Deuteronomy does not belong to YHWH, unlike the  in Leviticus. The latter is semantically related to the field of holiness and the former the exact opposite. Dozeman (2015:58) then spells out three differences between P and D with regard to

in Leviticus. The latter is semantically related to the field of holiness and the former the exact opposite. Dozeman (2015:58) then spells out three differences between P and D with regard to

1. There is no war setting in P and war is never holy in P, but it leads to soldiers becoming unclean. Dozeman uses Numbers 31:19-24 to argue this point. A war camp can never be holy for P as it is in Deuteronomy.

2. The Hebrew phrase

is unique to Priestly texts and refers to the transfer of an object from the profane to the sacred realm. I will also show that this argument is simply not true.

3. In P, the

objects become holy and, in D, they become

thus the opposite of holy. Yet, in both instances, they need to be shunned or separated from the people, but the shunning occurs in two different directions. For Deuteronomy,

is apparently far away from God and, therefore, needs to be shunned. For P,

enters the sphere of God and, therefore, needs to be shunned. I noted earlier that this interpretation of Deuteronomy 7:26 is not the only possible one.

For Dozeman's extensive argument, it is important to show these differences, since he wants to argue that Joshua is familiar with both traditions and tries to combine the two. The book of Joshua, like Deuteronomy, associates  with war, but, unlike Deuteronomy, does not regard it as

with war, but, unlike Deuteronomy, does not regard it as  It is indeed so that

It is indeed so that  never occurs in the Book of Joshua.11 On the one hand,

never occurs in the Book of Joshua.11 On the one hand,  in Joshua thus overlaps, to some extent, with

in Joshua thus overlaps, to some extent, with  in Deuteronomy, namely the association with war and destruction. On the other hand, the same could be said about

in Deuteronomy, namely the association with war and destruction. On the other hand, the same could be said about  in Joshua and P. There is some overlap, but how much exactly? In Joshua 6:17, Joshua dedicates the city and all that is in it to the Lord. For Dozeman, the link with P is this

in Joshua and P. There is some overlap, but how much exactly? In Joshua 6:17, Joshua dedicates the city and all that is in it to the Lord. For Dozeman, the link with P is this  and he understands it as changing the meaning of

and he understands it as changing the meaning of  to a sacrificial term.

to a sacrificial term.  is also used in Leviticus 27, where it clearly accompanies a sacrificial term. Dozeman (2015:59) then sums up his argument as follows:

is also used in Leviticus 27, where it clearly accompanies a sacrificial term. Dozeman (2015:59) then sums up his argument as follows:

The book of Joshua combines warfare and sacrifice into an ideology of holy war that represents a new teaching that is different from Deuteronomy and the P literature. ... The ideology of the ban is that war is not for the purpose of conquest, but of extermination; it is an act of sacrifice "to Yahweh" that is intended to bring peace to the land (Josh 11:23).

It is worth noting that Dozeman describes  in the Book of Joshua as a kind of sacrifice. This is supposedly a uniquely priestly understanding of

in the Book of Joshua as a kind of sacrifice. This is supposedly a uniquely priestly understanding of  I will now discuss whether a

I will now discuss whether a  is a kind of sacrifice. This question is not so much about

is a kind of sacrifice. This question is not so much about  in Priestly texts, but about

in Priestly texts, but about  in war texts from Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets. If there is already an element of sacrifice to

in war texts from Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets. If there is already an element of sacrifice to  in these texts, it would weaken Dozeman's argument that this element of sacrifice derives from Priestly texts.

in these texts, it would weaken Dozeman's argument that this element of sacrifice derives from Priestly texts.

4. A SACRIFICE OR NOT (IN DEUTERONOMY AND THE FORMER PROPHETS)?

There are obviously at least two schools of thought on this issue. On the one hand, scholars such as Stern (1991:173-174), Nelson (1997a:48) and Hieke (2014:1127) would, along with Dozeman, vehemently deny any overlap between a  and a sacrifice. On the other hand, Weinfeld (1972b:133-134), Milgrom (2001), Tatlock (2006) and Niditch (1993) all surmise that there is some element of sacrifice in the

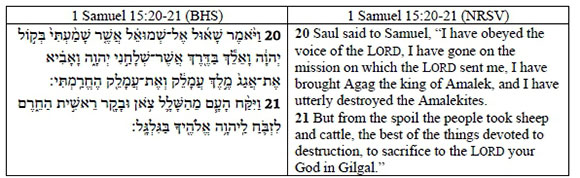

and a sacrifice. On the other hand, Weinfeld (1972b:133-134), Milgrom (2001), Tatlock (2006) and Niditch (1993) all surmise that there is some element of sacrifice in the  In many of these debates, the narrative in 1 Samuel 15 often plays a role and verses 20 to 21 are often cited. This is Saul's response to Samuel's claim that he was disobedient:12

In many of these debates, the narrative in 1 Samuel 15 often plays a role and verses 20 to 21 are often cited. This is Saul's response to Samuel's claim that he was disobedient:12

A great deal has been said about this text and, strangely enough, arguments suchasthatthereis nosacrifice inthis textoftenseemtooverlapwith the views of interpreters who are more sympathetic to Samuel than to Saul. Thus, Stern (1991:173-174) does not believe that Saul's excuse that they will sacrifice the best for YHWH ( ) is sincere, but rather a cover-up of his greed. Saul is understood to be greedy, like Achan in Joshua 7. Similarly, in his discussion of

) is sincere, but rather a cover-up of his greed. Saul is understood to be greedy, like Achan in Joshua 7. Similarly, in his discussion of  in Deuteronomy, Nelson (1997a:47-48) does not want to acknowledge that

in Deuteronomy, Nelson (1997a:47-48) does not want to acknowledge that  has anything to do with a sacrifice, since no altar or shrine was involved:

has anything to do with a sacrifice, since no altar or shrine was involved:

The foundational notion in sacrifice is a transfer in ownership from human possession to divine possession. But for the animals and humans involved, herem entailed no transfer to the heavenly world by means of burning. What was herem was killed or destroyed in order to render it unusable to humans, not to transfer its ownership. . The logic of herem meant that no sacrificial transfer could be conceived of, because anything in the herem state was already in the possession of Yahweh as spoil of war or by some other means.13

In response to Nelson, Tatlock (2006:173) pointed out that this definition of sacrifice is very close to Nelson's definition of what a  is. Nelson (1997a:44-45) describes the verb as "to transfer an entity into the herem state" and the noun as "the state of inalienable Yahweh ownership". Thus, both definitions of the verbs for

is. Nelson (1997a:44-45) describes the verb as "to transfer an entity into the herem state" and the noun as "the state of inalienable Yahweh ownership". Thus, both definitions of the verbs for  and sacrifice have "transfer" as the operative word. One also wonders why Nelson would argue that the purpose of

and sacrifice have "transfer" as the operative word. One also wonders why Nelson would argue that the purpose of  was to "render it unusable for humans?" Is this purpose ever stated? Not as far as I can see. It is clear that everything described as

was to "render it unusable for humans?" Is this purpose ever stated? Not as far as I can see. It is clear that everything described as  was destroyed.

was destroyed.

Yet to be totally destroyed does not disqualify something from being a sacrifice. On the contrary. The  of Leviticus 1 is totally burned. Even if it is utterly destroyed, this has nothing to do with keeping it out of humanhands;instead,it"represents thepuristformof divineservice" (Watts 2013:171). A fascinating question would be: When exactly does the

of Leviticus 1 is totally burned. Even if it is utterly destroyed, this has nothing to do with keeping it out of humanhands;instead,it"represents thepuristformof divineservice" (Watts 2013:171). A fascinating question would be: When exactly does the  of Leviticus 1 become the possession of YHWH? When the person presents it (v. 2), or puts his hands on it (v. 3), or when it is burned (v. 9)? One could ask: When does the

of Leviticus 1 become the possession of YHWH? When the person presents it (v. 2), or puts his hands on it (v. 3), or when it is burned (v. 9)? One could ask: When does the  become the possession of YHWH, in Joshua 6, for instance? When does the actual "transfer" take place? When Joshua declares it so in verse 17? When the declaration is executed in verse 21? If it is the latter, then Saul might have had a point. He would still have been in compliance when he killed the king later (Collins 2004:224). He has simply not yet concluded the act of

become the possession of YHWH, in Joshua 6, for instance? When does the actual "transfer" take place? When Joshua declares it so in verse 17? When the declaration is executed in verse 21? If it is the latter, then Saul might have had a point. He would still have been in compliance when he killed the king later (Collins 2004:224). He has simply not yet concluded the act of  I do not think, however, that these texts can really answer these questions. One should also note that, although Nelson agrees with Dozeman that

I do not think, however, that these texts can really answer these questions. One should also note that, although Nelson agrees with Dozeman that  in texts from Deuteronomy is not a sacrifice, Nelson believes that

in texts from Deuteronomy is not a sacrifice, Nelson believes that  belongs to God. Dozeman would not agree with this; a

belongs to God. Dozeman would not agree with this; a  is

is  and cannot belong to God.

and cannot belong to God.

Another sacrifice that would complicate matters is the  sacrifice in Leviticus 27, for instance. Verse 26 clearly states that the already belongs to YHWH and cannot be dedicated (Hiphil of

sacrifice in Leviticus 27, for instance. Verse 26 clearly states that the already belongs to YHWH and cannot be dedicated (Hiphil of  ) to him. By Nelson's logic, this would disqualify the from being described as a sacrifice. Yet, in Numbers 18, it is clear that a is indeed a sacrifice. In verses 17 and 18, the ritual is described in terms reminiscent of some of the sacrifices found in Leviticus 1-7, with blood dashed and the same

) to him. By Nelson's logic, this would disqualify the from being described as a sacrifice. Yet, in Numbers 18, it is clear that a is indeed a sacrifice. In verses 17 and 18, the ritual is described in terms reminiscent of some of the sacrifices found in Leviticus 1-7, with blood dashed and the same  that lingers (see Meyer 2017:141). The fact that something belongs to YHWH does not disqualify it from being regarded as a sacrifice. One could again ask: When does the become the possession of YHWH? At birth, or when killed? The text does not provide an answer.

that lingers (see Meyer 2017:141). The fact that something belongs to YHWH does not disqualify it from being regarded as a sacrifice. One could again ask: When does the become the possession of YHWH? At birth, or when killed? The text does not provide an answer.

To return to 1 Samuel 15, I find myself agreeing with scholars such as Tatlock (2011:42) and Milgrom (2001:2420-2421) that at least Saul thought that the  and indeed the war

and indeed the war  was something that overlapped with a sacrifice. Note also Saul's words quoted earlier that he took from the best of the

was something that overlapped with a sacrifice. Note also Saul's words quoted earlier that he took from the best of the  to sacrifice

to sacrifice  My point is that, even if

My point is that, even if  has some kind of sacrificial meaning in Joshua 6 expressed by

has some kind of sacrificial meaning in Joshua 6 expressed by  the authors of Joshua 6 could have adopted this idea not only from Leviticus 27. It is not a uniquely priestly idea. The idea of sacrifice might already have been present in the war

the authors of Joshua 6 could have adopted this idea not only from Leviticus 27. It is not a uniquely priestly idea. The idea of sacrifice might already have been present in the war  as in Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets. Many scholars also point out that, when Samuel eventually kills the king in verse 33, it is before Yahweh (

as in Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets. Many scholars also point out that, when Samuel eventually kills the king in verse 33, it is before Yahweh ( ); this sounds like a sacrifice, since Gilgal was a cultic site (Milgrom 2001:2420; Tatlock 2011:42; Niditch 1993:62).

); this sounds like a sacrifice, since Gilgal was a cultic site (Milgrom 2001:2420; Tatlock 2011:42; Niditch 1993:62).

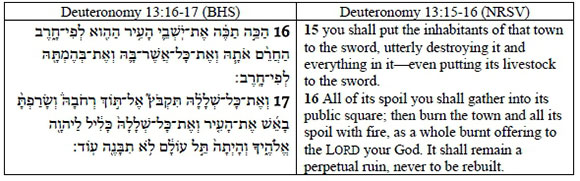

Other texts used by scholars such as Niditch (1993:63) and Tatlock (2011:43) include Deuteronomy 13:16-17, where the term  (another version of burnt offering) is used.14 The issue in this chapter is, in fact, an Israelite city that has started to worship other gods.

(another version of burnt offering) is used.14 The issue in this chapter is, in fact, an Israelite city that has started to worship other gods.

This  is also followed by

is also followed by  the term which Dozeman regards as Priestly. In short, to argue that the

the term which Dozeman regards as Priestly. In short, to argue that the  has a sacrificial meaning in Joshua 6 does not mean that there has to be a reception or reinterpretation of Priestly ideas.15 These ideas could have come from other places, and

has a sacrificial meaning in Joshua 6 does not mean that there has to be a reception or reinterpretation of Priestly ideas.15 These ideas could have come from other places, and  is certainly not a uniquely Priestly expression, since both texts use the expression in close proximity to the

is certainly not a uniquely Priestly expression, since both texts use the expression in close proximity to the  I am of the opinion that a sacrificial meaning was already present in some portrayals of the war

I am of the opinion that a sacrificial meaning was already present in some portrayals of the war  including the texts from Deuteronomy; it is not a uniquely priestly idea.

including the texts from Deuteronomy; it is not a uniquely priestly idea.

5. HOLY AND DESTRUCTIVE, ALL AT ONCE

Another issue with regard to the interpretation of  to which I referred earlier, is the debate about the two opposite meanings of

to which I referred earlier, is the debate about the two opposite meanings of  as both

as both  and holy. This is one of the cornerstones of Dozeman's argument, which he aligns with diachronic arguments (D and P) and which I have questioned earlier. Thus, Versluis (2016:234-237) finds it difficult to believe that the same word could have such different meanings belonging to different semantic domains. One should note that Versluis never equates

and holy. This is one of the cornerstones of Dozeman's argument, which he aligns with diachronic arguments (D and P) and which I have questioned earlier. Thus, Versluis (2016:234-237) finds it difficult to believe that the same word could have such different meanings belonging to different semantic domains. One should note that Versluis never equates  with

with  but that he consistently mentions destruction. Holiness and destruction have in common the ability to contaminate. Dozeman would want to disagree with this, since he is of the opinion that it only applies to the cultic

but that he consistently mentions destruction. Holiness and destruction have in common the ability to contaminate. Dozeman would want to disagree with this, since he is of the opinion that it only applies to the cultic  Versluis' (2016:237) solution is to attribute different meanings and semantic domains to the verb and the noun:

Versluis' (2016:237) solution is to attribute different meanings and semantic domains to the verb and the noun:

Thus, the meaning of the verb cnn almost always belongs to the semantic domain of destruction and devastation; the noun belongs to the domain of the sacred, indicating a certain sacral status of person or objects.

Versluis (2016:237) bases his understanding of the verb on the fact that it is usually not used with  , with the main exceptions being Leviticus 27:28 and Micha 4:13. This explains the "almost" in the above quote. This is, for instance, one of the differences he identifies between the use of the verb in the OT and in the Mesha Inscription, where it is used with the complement "for Ashtar Kemosh" (

, with the main exceptions being Leviticus 27:28 and Micha 4:13. This explains the "almost" in the above quote. This is, for instance, one of the differences he identifies between the use of the verb in the OT and in the Mesha Inscription, where it is used with the complement "for Ashtar Kemosh" ( ) (Versluis 2016:241).16 The two semantic domains are often combined when verb and noun are used together. In this instance, Versluis (2016:236) mentions Joshua 6:1717 and 1 Samuel 15:21. I did mention the latter text earlier in the discussion of

) (Versluis 2016:241).16 The two semantic domains are often combined when verb and noun are used together. In this instance, Versluis (2016:236) mentions Joshua 6:1717 and 1 Samuel 15:21. I did mention the latter text earlier in the discussion of  as a possible sacrifice. It is worth noting that the noun is used in 1 Samuel 15:21 and the verb in the previous verse. With regard to Joshua 6 and 7, I pointed out earlier that the verb is found only in chapter 6, with the noun occurring in both chapters. Could one thus argue that all of the examples of the verb belong to the semantic field of destruction and all of the nouns to the semantic field of holiness? Unfortunately, it is not that simple. In addition, the fact that, at times, the "holy" meaning and the "destructive" meaning can be combined in the same verse by means of the verb and the noun seems to undermine Versluis' argument.

as a possible sacrifice. It is worth noting that the noun is used in 1 Samuel 15:21 and the verb in the previous verse. With regard to Joshua 6 and 7, I pointed out earlier that the verb is found only in chapter 6, with the noun occurring in both chapters. Could one thus argue that all of the examples of the verb belong to the semantic field of destruction and all of the nouns to the semantic field of holiness? Unfortunately, it is not that simple. In addition, the fact that, at times, the "holy" meaning and the "destructive" meaning can be combined in the same verse by means of the verb and the noun seems to undermine Versluis' argument.

De Prenter (2012) presents another way of explaining the two different semantic fields, using insights from cognitive linguistics to explain the polysemous meaning of  . De Prenter (2012:474-475) is familiar with the work of Brekelmans, Lohfink and Stern and their basic diachronic argument that the term developed from a war

. De Prenter (2012:474-475) is familiar with the work of Brekelmans, Lohfink and Stern and their basic diachronic argument that the term developed from a war  to a peace

to a peace  . This coincides with a range of meanings from destruction to holiness. De Prenter (2012:477) makes use of prototype theory to explain how two meanings are possible for the same word. Her basic argument is that

. This coincides with a range of meanings from destruction to holiness. De Prenter (2012:477) makes use of prototype theory to explain how two meanings are possible for the same word. Her basic argument is that  is a "taboo concept" (De Prenter 2012:479). This is contra Stern (1991:224-225):

is a "taboo concept" (De Prenter 2012:479). This is contra Stern (1991:224-225):

I therefore argue that the "Grundbedeutung" or "abstract core meaning" of cnn is taboo, forbidden, prohibited. Two distinct senses are included in the Grundbedeutung of the term: something can be taboo because it belongs to the category of holiness or to the category of defilement. Depending on the context, the meaning of

overlaps with

and -

or with

or

Unlike Versluis, De Prenter does not make the distinction between verb and noun, but argues that both verb and noun can mean both. De Prenter (2012:482) is also much closer to Dozeman in arguing that the negative meaning of  is related to

is related to  and other terms such as

and other terms such as  and

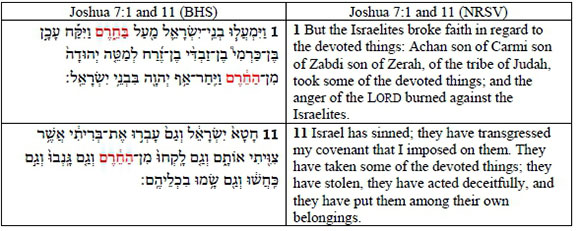

and  She argues that the first two occurrences of the noun in Joshua 7 (vv. 1 and 11) are an example of the "holiness" meaning:

She argues that the first two occurrences of the noun in Joshua 7 (vv. 1 and 11) are an example of the "holiness" meaning:

It is worth noting that the translation of the NRSV agrees with De Prenter's interpretation, but, at first glance, her argument seems slightly forced. There is no mention of any other words from the semantic domain of holiness, as one would find in Leviticus 27:28, or of  if we take Dozeman's argument seriously. That would at least imply that

if we take Dozeman's argument seriously. That would at least imply that  belongs to the realm of YHWH. De Prenter (2012:486) argues that, according to Joshua 7:21, Achan did, in fact, take silver and gold. This reminds us of 6:19, where silver, gold, bronze and iron are mentioned and declared holy. De Prenter (2012:486) then concludes that

belongs to the realm of YHWH. De Prenter (2012:486) argues that, according to Joshua 7:21, Achan did, in fact, take silver and gold. This reminds us of 6:19, where silver, gold, bronze and iron are mentioned and declared holy. De Prenter (2012:486) then concludes that

Joshua 7:1.11 are conceptually related to the Priestly texts I discussed earlier in which the noun

also refers to consecrated objects.

Her arguments could thus be used to support, at least partially, Dozeman's basic argument.18 It should be clear though that both attempts by Versluis and De Prenter to account for different meanings have contradictory results. For De Prenter, only the first two nouns of chapter 7 refer to holiness. For Versluis, all of them do. In the last section of this article, I will attempt to integrate all of the above ideas into a coherent reading of  in Joshua 6 and 7.

in Joshua 6 and 7.

6. DISCUSSION OF IN JOSHUA 6 AND 7 AND THE QUEST FOR PRIESTLY IDEAS

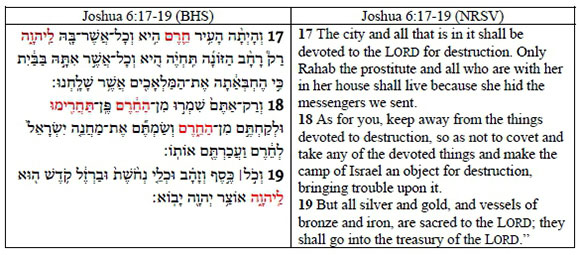

The noun and the verb occur in close proximity in Joshua 6 only in the following verses:

In verse 17, it is clear that the city will become  and everything in it shall "be for YHWH", with the exception of Rahab and her house. Verse 18 warns that the addressees should keep away from the

and everything in it shall "be for YHWH", with the exception of Rahab and her house. Verse 18 warns that the addressees should keep away from the  otherwise they themselves will become

otherwise they themselves will become  In my opinion, this verse implies some kind of contamination, similar to that in Deuteronomy 7:26. It is also the only instance in Joshua 6 and 7 where the verb occurs. According to Versluis, these nouns should all have the meaning of the "sacred", but for De Prenter they belong to the category of defilement. The two arguments lead to opposing results. The vast majority of commentators accept that what we have in verse 19 also refers to the

In my opinion, this verse implies some kind of contamination, similar to that in Deuteronomy 7:26. It is also the only instance in Joshua 6 and 7 where the verb occurs. According to Versluis, these nouns should all have the meaning of the "sacred", but for De Prenter they belong to the category of defilement. The two arguments lead to opposing results. The vast majority of commentators accept that what we have in verse 19 also refers to the  , but that is not so apparent.19

, but that is not so apparent.19

The word is never used; instead, the four kinds of metal are called holy ( ); they are also "for YHWH" and are, more specifically, destined for the treasury. The question arises as to whether these metals are

); they are also "for YHWH" and are, more specifically, destined for the treasury. The question arises as to whether these metals are  or not? Is holy thus a different category? Is what we have in verse 19 a higher category than what we have in verse 17, something which does not get destroyed, but is kept? It could very well be.

or not? Is holy thus a different category? Is what we have in verse 19 a higher category than what we have in verse 17, something which does not get destroyed, but is kept? It could very well be.

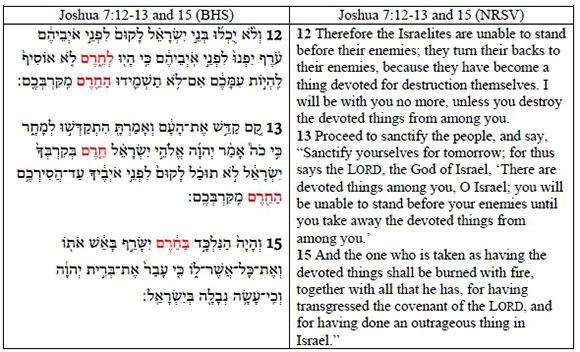

With regard to Joshua 7, the noun is found in verses 1, 11, 12, 13 and 15. The first two verses are found in the table above where De Prenter's work is discussed. She is of the opinion that these two are examples of where  would mean holy and, in her argument, she links these examples via 7:21 to 6:19 and the metals found there.

would mean holy and, in her argument, she links these examples via 7:21 to 6:19 and the metals found there.  occurs in the following verses:

occurs in the following verses:

It appears that verses 12 and 13 support the reading in 6:18 that the  is contaminating, and that they have thus become

is contaminating, and that they have thus become  themselves (McConville & Williams 2012:39; Rösel 2011:117). Verse 15 also reminds us of the previously discussed Deuteronomy 13:16, where everything is burned with fire (there

themselves (McConville & Williams 2012:39; Rösel 2011:117). Verse 15 also reminds us of the previously discussed Deuteronomy 13:16, where everything is burned with fire (there  , here

, here  ) (Dozeman 2015:360). In verse 15, the word

) (Dozeman 2015:360). In verse 15, the word  is used to describe the bad thing that was done to Israel. This expression

is used to describe the bad thing that was done to Israel. This expression

is not especially related to the ban but is used mostly for grave crimes in the sexual sphere that endanger the community (Rösel 2011:115).

Verse 13 also makes it clear that the people can only be sanctified by removing the  from their midst. According to Dozeman, this cannot be a priestly idea, since the war camp can never be holy. In his commentary on Deuteronomy 7, Otto (2012:880) argues that the motives to acquire gold and silver, as mentioned in 7:21, also occur in Deuteronomy 7:25 and not only in Joshua 6:19:

from their midst. According to Dozeman, this cannot be a priestly idea, since the war camp can never be holy. In his commentary on Deuteronomy 7, Otto (2012:880) argues that the motives to acquire gold and silver, as mentioned in 7:21, also occur in Deuteronomy 7:25 and not only in Joshua 6:19:

Mit den Motiven von Gold und Silber wird eine Verbindung zwischen Dtn 7, dem Dekalog und Jos 6-7 hergestellt. Gold und Silber der Stadt Jericho seien für YHWH "geweiht".20

The point is that much of the story of Joshua 6 and 7 has far more intertextual links with texts from Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets than with texts from Priestly literature.

7. CONCLUSION

I have endeavoured to argue that the  as found in Joshua 6 and 7, shows hardly any sign of being influenced by Priestly understandings of the term. If there is an element of sacrifice present in Joshua 6 and 7, then it is also present in both Deuteronomy 13 and 1 Samuel 15, where the expression

as found in Joshua 6 and 7, shows hardly any sign of being influenced by Priestly understandings of the term. If there is an element of sacrifice present in Joshua 6 and 7, then it is also present in both Deuteronomy 13 and 1 Samuel 15, where the expression  also occurs. I have also attempted to show that the direct link between

also occurs. I have also attempted to show that the direct link between  and

and  is based only on Deuteronomy 7:26 and that there are other ways of interpreting that text. In short, there seems to me to be more of an intertextual link between

is based only on Deuteronomy 7:26 and that there are other ways of interpreting that text. In short, there seems to me to be more of an intertextual link between  in Joshua 6 and 7 and texts from Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets than with Priestly literature. In both Joshua 6 and 7 and Deuteronomy 13,

in Joshua 6 and 7 and texts from Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets than with Priestly literature. In both Joshua 6 and 7 and Deuteronomy 13,  seems to have the ability to contaminate, the solution usually being utter destruction, sometimes including burning by fire.

seems to have the ability to contaminate, the solution usually being utter destruction, sometimes including burning by fire.

One last thought: It is well known that Douglas' work has had a great impact on the study of the Leviticus and other Priestly texts. Douglas' (1966:41) concept of "matter out of place", although used to describe Priestly views of impurity, also seems appropriate for the problem caused by  in Joshua 7. When

in Joshua 7. When  is present "in your midst", it causes a major problem, making it impossible for YHWH to be present. The solution is to destroy the "matter out of place" and, although this might sound like a very Priestly idea, it also seems to be present in very un-Priestly texts such as Deuteronomy 7 and 13. In both instances, objects associated with foreign gods are brought into the midst of Israel. These are also clearly "matter out of place", or more specifically "gods out of place".

is present "in your midst", it causes a major problem, making it impossible for YHWH to be present. The solution is to destroy the "matter out of place" and, although this might sound like a very Priestly idea, it also seems to be present in very un-Priestly texts such as Deuteronomy 7 and 13. In both instances, objects associated with foreign gods are brought into the midst of Israel. These are also clearly "matter out of place", or more specifically "gods out of place".

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Brekelmans, C.H.W. 1959. De Herem in het Oude Testament. Nijmegen: Centrale Drukkerij. [ Links ]

- Butler, T.C. 2014. Joshua 1-14. Second edition. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. Word. [ Links ]

- Clines, D.J.A. (Ed.) 1998. The dictionary of Classical Hebrew. Volume 4. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. [ Links ]

- Collins, J.J. 2004. Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

- De Prenter, J.A. 2012. The contrastive polysemous meaning of in the Book of Joshua: A cognitive linguistic approach. In: E. Noort (ed.), The Book of Joshua (Leuven: Peeters, BETL 250), pp. 473-488. [ Links ]

- Douglas, M. 1966. Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

- Dozeman, T.B. 2015. Joshua 1-12. A new translation with introduction and commentary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Anchor Yale Bible 6B. [ Links ]

- Fritz, V. 1994. Das Buch Josua. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. HAT 1/7. [ Links ]

- Hieke, T. 2014. Levitikus 16-27. Freiburg: Herder. HTK. [ Links ]

- Knauf, E.A. 2008. Josua. Zürich: TVZ. Zürcher Bibelkommentare. [ Links ]

- Lohfink, N. 1982. hräram. In: G.J Botterweck & H. Ringgren (eds), Theologisches Wörterbuch zum Alten Testament. Band III (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer), pp. 193-212). [ Links ]

- McCoNViLLE, J.G. & Williams, S.N. 2010. Joshua. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. Two Horizons. [ Links ]

- Meyer, E.E. 2017. Ritual innovation in Numbers 18? Scriptura 116:133-147. [ Links ]

- MiLGROM, J. 2001. Leviticus 23-27. A new translation with introduction and commentary. New York: Doubleday. Anchor Bible 3B. [ Links ]

- Nelson, R.D. 1997a. herem and the Deuteronomic social conscience. In: Vervenne, M. & Lust, J. (eds), Deuteronomy and Deuteronomic literature. Festschrift C.H.W. Brekelmans (Leuven: Peeters, BETL 133), pp. 39-54. [ Links ]

- Nelson, R.D. 1997b. Joshua. A commentary. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

- NiDITCH, S. 1993. War in the Hebrew Bible: A study of the ethics of violence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

- Nihan, C. 2007. From Priestly Torah to Pentateuch. A study in the composition of the Book of Leviticus. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. FAT II. [ Links ]

- otto, E. 2012. Deuteronomium 4,44-11,32. Freiburg: Herder. HTK. [ Links ]

- otto, E. 2016. Deuteronomium 12,1-23,15. Freiburg: Herder. HTK. [ Links ]

- Rösel, H.N. 2011. Joshua. Leuven: Peeters. HCOT. [ Links ]

- Snyman, S.D. 2015. Malachi. Leuven: Peeters. HCOT. [ Links ]

- Stern, P.D. 1991. The Biblical HEREM. A window on Israel's religious experience. Atlanta: Scholars Press. [ Links ]

- Tatlock, J.R. 2006. How in ancient time they sacrificed people: Human immolation in the Eastern Mediterranean basin with special emphasis on Ancient Israel and the Near East. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Michigan: University of Michigan. [ Links ]

- Tatlock, J.R. 2011. The place of human sacrifice in the Israelite cult. In: Eberhart, C.A. (ed.), Ritual and metaphor. Sacrifice in the Bible (Atlanta: SBL, Resources for Bible Study 68), pp. 33-48. [ Links ]

- Van der Molen, W.K. 2008. Een ban om te mijden. Bouwstenen voor een bijbels-theologische verkenning. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. [ Links ]

- Versluis, A. 2016. Devotion and/or destruction? The meaning and function of Din in the Old Testament. Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 128(2):179-197. https://doi.org/10.1515/zaw-2016-0017 [ Links ]

- Watts, J.W. 2013. Leviticus 1-10. Leuven: Peeters. HCOT. [ Links ]

- Weinfeld, M. 1972a. Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomistic school. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

- Weinfeld, M. 1972b. The Worship of "Molech" and of the Queen of Heaven and its background. Ugarit Forschungen 4:133-154. [ Links ]

1 Under "P literature", Dozeman seems to understand many other texts that could be regarded as post-P or even post-H. For instance, Dozeman (2015:57) would discuss Leviticus 27 under "P literature", but this chapter is usually regarded as one of the last added to the book of Leviticus, even after the Holiness Code (H). See, for instance, the work of Nihan (2007:552). Dozeman is not totally inaccurate when he refers to "P literature", since scholars such as Nihan would regard these later chapters as added by later generations of priests.

2 Strangely enough,  is the last Hebrew word in the Protestant Old Testament and the Corpus Propheticum (in the Hebrew Bible), which takes us to the expertise of Fanie Snyman, namely Malachi. This article is presented as a token of appreciation for his academic contribution to the study of the Old Testament and the training of ministers. In his discussion of the "ban", Snyman (2015:181) argues that this "ominous end" is a strategy of Yahweh to convince his hearers to rather pursue reconciliation between fathers and sons. A further avenue to explore would be whether the understanding of

is the last Hebrew word in the Protestant Old Testament and the Corpus Propheticum (in the Hebrew Bible), which takes us to the expertise of Fanie Snyman, namely Malachi. This article is presented as a token of appreciation for his academic contribution to the study of the Old Testament and the training of ministers. In his discussion of the "ban", Snyman (2015:181) argues that this "ominous end" is a strategy of Yahweh to convince his hearers to rather pursue reconciliation between fathers and sons. A further avenue to explore would be whether the understanding of  in this verse is closer to either P or D. I would guess the latter. The fact that Horeb is mentioned in Malachi 3:22 as in Deuteronomy would support such a guess. Still, in my opinion, to conclude a prophetic book with this word feels rather daunting.

in this verse is closer to either P or D. I would guess the latter. The fact that Horeb is mentioned in Malachi 3:22 as in Deuteronomy would support such a guess. Still, in my opinion, to conclude a prophetic book with this word feels rather daunting.

3 For a brief overview of how many modern European languages used a term that was originally used for excommunication out of the synagogue in the Middle Ages, see Brekelmans (1959:44) or Fritz (1994:72).

4 Joshua 6:17, 18 (thrice); 7:1 (twice), 11, 12 (twice), 13 (twice), 15; 22:20.

5 Joshua 2:10; 6:18, 21, 26; 10:1, 28, 35, 37, 39, 40; 11:11, 12, 20, 21.

6 The noun occurs in Leviticus 27:21, 28 (twice), 29 and in Deuteronomy 7:26 (twice); 13:18. The verb occurs in Leviticus 27:28 and 29 and in Deuteronomy 2:34; 3:6 (twice); 7:2 (twice); 13:16; 20:17 (twice). These are all in the Hiphil, with the exception of Leviticus 27:29, which is in the Hophal.

7 Serves in Deuteronomy as designation of cultic and ethical demarcation.

8 The best overview of the contributions of Brekelmans, Lohfink and Stern is found in Van der Molen (2008:108-123). She shows how all three offer similar arguments and disagree on smaller issues. Both Brekelmans (1959:163-165) and Lohfink (1982:207-208) are of the opinion that there is a third kind of  found in Exodus 22:19, namely

found in Exodus 22:19, namely  as punishment. These would be the instances where the verb is found in the Hophal.

as punishment. These would be the instances where the verb is found in the Hophal.

9 Texts associated with this oldest meaning of the war  include Numbers 21:2-3; Joshua 6:21; 1 Samuel 15:3, 8, 9 (twice), 15, 18, 20.

include Numbers 21:2-3; Joshua 6:21; 1 Samuel 15:3, 8, 9 (twice), 15, 18, 20.

10 Stern (1991:133-134) would add Numbers 18:14.

11 It was used only once in Deuteronomy with reference to

12 According to the table, Dozeman (2015:55) sums up all of the different occurrences of cnn in the OT; he understands the example from verse 20 as a case of the war  and the one in verse 21 as a cultic

and the one in verse 21 as a cultic  Since his commentary is not on 1 Samuel, he never explains his understanding of these different meanings in the same chapter.

Since his commentary is not on 1 Samuel, he never explains his understanding of these different meanings in the same chapter.

13 For asimilarargument,see Hieke (2014:1127).

14 See Clines (1998:425) or Tatlock (2011:43).

15 Nelson (1997a:47) argues that the use of vpa in this text "is clearly intended as a metaphor", an image "illustrating the frenzied attack of Yahweh's sword". See the response from Tatlock (2011:43-44). In the most recent commentary on Deuteronomy, Otto (2016:1265) understands this verse to mean that the city becomes a sacrifice to YHWH. Yet, for him, it should be read in a post-exilic context and is, in fact, a subtle reference to what happened to Jerusalem.

16 As pointed out by Brekelmans (1959:51).

17 Versluis is referring to the verse in English translations. In the BHS, verse 18, the addressees are the subject of the verb in the Hiphil. One could simply translate the verb, in this instance, as "become  ", although a Hophal would have made more sense. As mentioned earlier, Brekelmans (1959:52) would regard these two examples as having the original religious meaning.

", although a Hophal would have made more sense. As mentioned earlier, Brekelmans (1959:52) would regard these two examples as having the original religious meaning.

18 Dozeman (2015:144) mentions this essay by De Prenter in his bibliography, but never engages with her work.

19 See English commentators such as Nelson (1997b:94), Butler (2014:377) or McConville & Williams (2010:34). German scholars usually offer a diachronic solution. Fritz (1994:73) views this verse as part of an additional layer, which offers a "Neuinterpretation" of  although, to complicate matters, verses 17 and 18 belong to the same layer. Fritz does not really perceive the tension. Knauf (2008:72) understands this verse to answer a question left unanswered by Numbers 31:22-23: What should happen to precious metals after they have been cleansed by fire? For Knauf, this verse is clearly a supplement. Van der Molen (2008:162) is one of the few scholars who believes that verse 19 refers to something else (see n. 524). Rösel (2011:102) argues that the metals are not part of the ban, but are consecrated, meaning something other than the ban, in other words, not being destroyed.

although, to complicate matters, verses 17 and 18 belong to the same layer. Fritz does not really perceive the tension. Knauf (2008:72) understands this verse to answer a question left unanswered by Numbers 31:22-23: What should happen to precious metals after they have been cleansed by fire? For Knauf, this verse is clearly a supplement. Van der Molen (2008:162) is one of the few scholars who believes that verse 19 refers to something else (see n. 524). Rösel (2011:102) argues that the metals are not part of the ban, but are consecrated, meaning something other than the ban, in other words, not being destroyed.

20 With the motives of gold and silver a link is made between Deuteronomy 7, the Decalogue and Joshua 6-7. Gold and silver of the city Jericho would be dedicated to YHWH.