Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.38 n.1 Bloemfontein 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v38i1.6

ARTICLES

Prayer in the Old Testament as spiritual wisdom for today1

C. Lombaard

Department of Christian Spirituality, University of South Africa. E-mail: christolombaard@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The discipline of Biblical Spirituality, with its dual focus on ancient text and modern application, provides the methodological framework for this article. The modern sociological interest in religion, spirituality and prayer is indicated, but not explored, with a shared wisdom orientation in aspects of Old Testament life and in the currently unfolding post-secular religio-cultural climate that forms the bridge between the ancient and the modern in the analysis of prayer. The remainder of this contribution focuses on Deuteronomy 6:4 - the famous Sh'ma prayer -and its historical implications. The editorial history of the book of Deuteronomy, following the theory of E. Otto, forms the basis for understanding more precisely the impact of the Sh'ma in ancient Israel. The link of this prayer to Law inhibited much of its inherent power, testifying to a change in dominant spirituality within post-exilic Judaism. This has had far-reaching implications in the Judeo-Christian history of theology, particularly relating to the grace-law emphases, as indicated in this article, but left to unfold more fully in further research.

Keywords: Prayer, Wisdom, Old Testament

Trefwoorde: Gebed; Wysheid; Ou Testament

...con le ginocchia della mente inchine (Casanova, quoting Petrarch)2

1. THE METHODOLOGICAL DOUBLE ENTENDRE OF BIBLICAL SPIRITUALITY

For the purposes of this article, the topic of prayer is approached from two perspectives. From within Old Testament scholarship, a review of thematic studies on prayer in the Old Testament was combined with a more detailed analysis of a single short prayer, but one of the most influential in human history, the Sh'ma in Deuteronomy 6:4. This is followed by an investigation into modern sociological approaches to prayer, namely Rosa's Social acceleration: A new theory of modernity (2013). Rosa's approach is the broadest on prayer and, more specifically, on religion. Flanagan & Jupp's The sociology of spirituality (2007) is closer to prayer, yet still focuses more on spirituality than on prayer itself. Two further editions have been published, namely Giordian & Woodhead's Prayer in religion and spirituality (2013) and A sociology of prayer (2015). These sociological works are not explicitly referenced in this article, but have informed the interpretative framework of the interaction between prayer and individual and society, as it relates to both the ancient and modern worlds.

This two-directional approach is in keeping with the methodology developed within the subdiscipline of Biblical Spirituality,3 which combines historically oriented exegetical investigations into the ancient texts with contextually oriented phenomenological investigations into the present, in both cases intentionally recognising explicit and implicit impulses of faith. Though it may at first seem wanting, even wanton, to relate what appears to be different worlds (pre-modern Judea and the diversity of contexts in our world) and methods (critical exegesis and analytical phenomenology) into one model of studies, it turns out not to have been entirely as random as might be a fusion cuisine dish. Apart from Max Weber's insight that ideas have historical influence across time (Otto 2004:181-188), reformulated under a genetic metaphor with the concept of "meme", as a self-perpetuating cultural habit made famous by Dawkins (1976), I have also advanced another religio-cultural angle (Lombaard 2015:82-95). A wisdom-kind of orientation to life-and-the-divine characterises a strong strand of orientation within the Old Testament life world as much as in our currently unfolding (post-secular) life world. That parallel orientation opens up an area of resonance, in which ancient texts and current contexts "find" each other appreciatively (Lombaard 2015:91-92):

...for the most part, God is elusive. The "Wisdom God" can at best be seen to be involved behind the scenes of life's daily stage. True to the reality of daily living in which God cannot be empirically observed, the Old Testament's Wisdom literature in a phenomenologically parallel manner hardly mentions God. That God is not-t/here-yet-t/here is within the ancient Near Eastern Wisdom perception not a philosophical conundrum as it had been for Greek contemporaries, nor did it require the kind of spiritual word play to formulate the complex mysteries of life and the holy as we find it in classical Buddhism or Hinduism; it is, more simply, an orientation to the divine in a life world in which it is impossible to live agnostically or atheistically. Religion is ubiquitous. God/s cannot not exist; humans cannot live outside the domain of the spiritual. God's existence and/or presence in human affairs is implicit - that is part of human wisdom; only rarely is God's existence and/or presence made explicit...

It is within such a convergence of the ancient and the modern that the phenomenon of prayer lies, as will become clear from the argumentation below. Avisar (with special appreciation for the Sh'ma [Avisar 1985:257-261]) also sensed this particular convergence, when he writes:4

La preghiera come grido spontaneo nei momenti d'angustia è universale e antica come l'uomo. La preghiera come istituzione religiosa, come rito quotidiano e manifestazione pubblica, è invenzione dell'ebraismo. Tale forma di preghiera è nata, si può supporre, già dopo la distruzione del Primo Tempio, ma si è pienamente sviluppata e consolidata, imponendosi come una delle basi della vita ebraica, dopo la caduta del Secondo Tempio. La casa di preghiera non essendo legata a un luogo determinato, ma sorgendo dovunque si stabilisse una comunità ebraica, acquistò col tempo una straordinaria potenza spirituale; e le orazioni vi assunsero funzioni e significati che oltre-passarono quelli del culto sacrificale. La preghiera pubblica è del resto uno dei grandi contributi dell'ebraismo alla civiltà umana... (Avisar 1985:255).

2. PRAY, DO TELL...

It seems like a moment of almost liturgical orderliness that many writings on prayer propose a list of forms of prayer, all different, none exhaustive, often with substantial correspondence, and commonly with the rhetorical intent to orient the mind on the inexact, yet exacting nature of the phenomenon. Not to break that mould, in this instance: prayer as an act and as a topic of writing spans a vast array of genres and practices:

• from highly academic reflections in a warm, spiritually nourishing style (Hunziger & Peng-Keller 2014) to highly academic studies in a detached, analytical style (Brümmer 2008, 2011);

• from informed popular (non-academic) guides (Muller 2016) to piously populist inspirational texts (Omartian 1997, and the subsequent series);

• from the simplest act of bedtime piety or a subdued mumble for a blessed meal to the rites of faith at a Last Supper, a holy communion or a last rite, to an initiation into holy orders or a presidential inauguration;

• from individuals' exclamations in fear or despair or - the exact same appellations (adorations? blasphemies?) - in passion, to an at times overlooked aspect of prayer: the deepest of silences:

Hier word nie verwys na die afwagtende stilte sodat die ander kan praat nie, of na die ongemaklike stilte wat van wantroue getuig nie, of na die simpatieke stilte wat meegevoel betoon nie, of na die leë stilte waar niemand iets te sê het nie, maar na die volle stilte waarin die ontoereikendheid van elke taal bevestig word, en wat meer welsprekend is as woorde5 (De Beer 1983:166, with reference to Jaspers 1956a, 1956b);

• from supplication to thanksgiving, and more, in Psalms composed, cultically established, textually canonised and then ecclesially and personally re-prayed and reflected upon through millennia, giving rise to a recent academic tradition of writing on the Psalms and spirituality. Apart from much of Waaiman's oeuvre, such as Waaijman (2004), also Brueggemann (2002), and expanding on him, Firth (2005); the most historically oriented among these works are Stuhlmueller (2002; Lombaard 2006:909-929); in addition, McConville (2013:5674) and Schneiders (2013:128-150), among her many contributions to establishing the discipline of Biblical Spirituality; see also Eaton (2004, 2006);

• from ancient liturgical sayings to the atheist-Jewish French philosopher of post-modernity Derrida, daily merely touching his prayer shawl;

• from religious trend books, such as on the prayer of Jabez (Wilkinson 2000) to popular existentialism à la Eat, pray, love in both book (Gilbert 2006) and motion picture (2010; www.imdb.com/title/tt0879870/) formats;

• from "cool" teen pseudo blasphemies - "Oh Em Geeee!" - to robust rock lyrics (Lombaard 2018);

• from empirical dissertations such as Ap Siôn (2010) to cartoons on prayers in our digital age:

3. A-CHOIRED WHISPERS: DEUTERONOMY 6:4

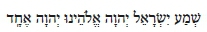

= Hebrew: Sh'ma Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Ehad

(= Aramaic: Sh'ma Yisrael Sh'mah Eloheinu Sh'mah Ehad)

= English: Hear, Israel, YHWH/The Lord our God YHWH/The Lord [is] one.7

Prayer in the Old Testament, as much as in any other context, constitutes a way of life (Human 2001:58), offering "verskillende blikpunte en beklemtonings op hierdie gemeenskap-ervaring tussen mens en God".8Neither the ubiquity of prayer nor its extensive reach means that only a-contextual generalisms on this topic should satisfy us - this relating as much to the biblical texts as to the sociological works mentioned earlier. The who, the where, the when and the how remain insightful particulars of prayers. It is not only the devil that is in the details; rather, with prayers - and with canonised prayers perhaps more so than in, for instance, free prayers - the specificities are part of the God-shaped whole.

The characterisation of Old Testament prayers simply according to their formats (Westermann 1978:136-138; Reventlow 1986:83-118) is, however, no longer possible, in this instance not because of the choice for a text-immanent rather than a historical approach (as in Kloppers 1989:1-2), but because the dating possibilities of the Old Testament texts have been changed a great deal, through recent scholarship, with, as a prominent example, the highly contested field of Pentateuch theory (among which the understanding of Otto (2000) is taken as basis, in this instance), rendering (so-called) theory-less textual analyses obsolescent for scholarship (Le Roux 2001:444-457).

The latter is valid even for an invocation such as the Sh'ma, which has been recited for some twenty-six centuries, if we want to understand its origins within the Bible text. The concision of this text as much as the piety that surrounds it, however, veil its intricacies. These six Hebrew words exhibit an involved complexity of syntax (Kraut 2011:482), with every aspect of this aphorism having been contested exegetically and hermeneutically, and with the findings directly affecting the theology understood to be alive in the Sh'ma. (This relation is evident in footnote 7 above.)

This appeal of the Sh'ma is within its textual context not uniquely paraenetic, since the larger textual context, Deuteronomy 6:1-9 (+ Deut. 6:10-15) + Deuteronomy 6:16-19 (Otto 2012:781-784), is such too. This, as part of the contents of these texts establishing a religious identity connected with the Moses speech at Horeb, as related in Deuteronomy 5, as a highly stylised reimagination of the Sinai events in Exodus, and from that, then, as a purposive reimagination of the character of 6th-century Israel. The retelling of history in Deuteronomy 5 shapes the new identity of Israel. Deuteronomy 5 reconstitutes the earlier9 Exodus narratives: in a post-exilic setting, after the destruction of the Babylonian exile (586-539 BCE) and during a difficult relationship period between those who had been left undeported in Jerusalem and its environs (in 597 and 586 BCE) and those among the (political, religious, economic and educational) elite who had returned from Babylon (from 539 BCE onwards), a known national history of unification under YHWH after escaping Egypt is re-imagined, in order to (attempt to) constitute a newly unified post-exilic identity in Judea (Zahavy 1989:33-40). The Sh'ma plays a key role in this identity formation, since it summarises succinctly and in wholly religious terms, for the (newly reconstructed) post-exilic audience, the (newly reconstructed) Horeb events of Deuteronomy 5.

However, in an earlier version of the Deuteronomy text (though not of the earliest version of the text, the core of which we have in Deut. 12-26, which goes back to the 622 BCE Josianic reformation; 2 Kings 23-24), slightly predating the exile, the Sh'ma formed the opening words of that version of the book of Deuteronomy (Otto 2012:644, 785). The importance of the book of Deuteronomy as putative Moses speech giving Israel its "Constitution", commencing with the Sh'ma prayer, can hardly be grasped. In the subsequent editorial framing work on the book, these strong, opening Moses words are picked up and the intent made more didactic by the repetition of the term "hear", Sh'ma, in Deuteronomy 6:3 and, more directly, in Deuteronomy 5:1 - the latter becoming, significantly, the opening to the Decalogue (Janzen 1987:294-295, drawing on Miller 1984:17-29).

All of this is styled as Moses' words related to a covenant set up at Horeb, at which the relationship between YHWH and the (at different times reconstituted) people of Israel is formalised anew. The dual names for God,  , namely YHWH and God in the relational formulation "YHWH our God", play an equally connective role between the initial Sh'ma formulation in Deuteronomy 6:4 and the later Deuteronomy 5:1 introduction to the Decalogue. Confession and Law from now on become related.

, namely YHWH and God in the relational formulation "YHWH our God", play an equally connective role between the initial Sh'ma formulation in Deuteronomy 6:4 and the later Deuteronomy 5:1 introduction to the Decalogue. Confession and Law from now on become related.

Consequently, the orientation to Law in the younger text (Deut. 5:1) on what it means now, post-exilically, that YHWH is the God of Israel adds a legal dimension to the Sh'ma that it had not had. Faith is changed. Such a reinterpretation of the God-Israel relationship, as one cast in laws and regulation, is typical of Deuteronomistic theology (that developed during and after the Babylonian exile, becoming the dominant theology), as it tries to answer the searching questions related to the sense of this destructive exile tragedy.10 This dominant theology is subsequently so powerfully established in the religious life of Israel and in the editorial activity on the text of Deuteronomy (and of much of the remainder of the Pentateuch, extending also to the Prophetic literature of the Old Testament, known as their Deuteronomistic redactions) that neither in the faith of Israel nor in Christian belief and theologising has it become possible to disentangle Deuteronomy 6:4 from Deuteronomy 5:1. In other words, to disentangle prayer from law.

One form of spirituality has been replaced by another. The effects of this in subsequent religious history have been dramatic. The call to faith in God (i.e., the Sh'ma), and in God alone (see footnote 7 above), is now (from the time that Deut. 6:4 has been connected to Deut. 5:1) understood as being a call to adherence - a theological move without which, later, both Islam and Calvinism, for instance, would be hardly imaginable. Now, on the grace of faith follows implicitly and immediately injunctions on how this faith ought to be lived.11

The critical question has to be asked as to whether grace and law entwined is an orientation to God and people that is entirely constructive; this question goes to religious foundations, particularly in light of how prevailing this (Deuteronomistic) theological apparatus had been in the faith of post-exilic Judaism and from there on, in different ways across three religions. Underlying this question is the oft-assumed primacy of religious experience (cf. cautionary, Biernot & Lombaard 2017: 1-12), which means that the presence of God is not constituted first by Law. One of the premises on which faith is based remains the direct encounter with the Divine (with the classical modern texts in this regard, James 2002 [1902] and Otto 1917, 1923) - something which had been constitutive for Prophetic theology in the Old Testament, and which lies as much at the heart of prayer - such as the Sh'ma or any of the forms listed under section 2 above, and others - as it does of spirituality ancient and modern, and as an academic discipline.

Would it, in light of this reasoning, be too much to say that the Sh'ma, as understood prior to the post-exilic (Deuteronomistic) connection with the Decalogue, constituted a more direct, less refereed orientation towards God?12 Does the Sh'ma represent an unmediated relationship with YHWH?

4. OUR NUMBER'S UP

But, has such "immediacy" perhaps not been altogether lost? The Sh'ma still retains two natures: as a confession and as an exhortation. As a mantra (to employ a somewhat tangential term) that should be repeated at all times,13the Sh'ma functions as a prayer pronouncement and a rite. In this sense, the Sh'ma exhibits a dual character as at once a call to faith and itself a confession of faith, namely as a ritualistic prayer. In a compact way, therefore, the Sh'ma incorporates two genres of prayer into one and does so moreover as both a private incantation and a public prayer. The latter public prayer aspect can, in addition, be found in practice, when the prayer is uttered communally or by one person in the presence of others, on the one hand, or, by implication, when these few words are employed privately, yet clearly has the sense of placing the one who prays into a community of believers, on the other.

Whether this community is a political or a religious entity is, in a sense, a modern question, since in the late pre-exilic and post-exilic communities in Judea, in which this prayer became a regular liturgical expression, the relationship (or more accurately, the division, namely the non-division) between political and religious identities had been constituted differently than is the case in modern liberal democracies, determined as we are in all respects by the Enlightenment (yet never uncontentiously so - Benson & Bussey 2017), and therefore by the previously impossible separation between such spheres of life. Yet, these cultural-historical differences at best relativise such a question; it does not render it illegitimate. The individual-communal mutual implication taken up by the Sh'ma places this matter of the nature of faith continuously on the foreground.

It seems that even a small prayer suggests large religious concerns, be they whispered or choired.

The change in grammatical number between the second person singular and the second person plural, which comprises one of the central markers for exegesis of these Deuteronomy chapters (Otto 2012:781-784), is thus in the Sh'ma, in a certain sense, collapsed into a kind of existential summary: what the you-plural believe is what the you-singular believes, and equally so vice versa. The modern impulses from politics on the importance of the individual, which is both mirrored and intensified in the strong impulse in and from Pietism on what I believe (experience and confess), is absent in the Sh'ma. For a moment to parody modern sports team talk: there is no I in Sh'ma.

This, not only in the content of the saying, but also in the way it is used: when an individual utters the Sh'ma, there is no reference to the individual him- or herself. The referentiality is wholly external, to what is believed in the group, in Whom is believed, and what is believed about this Whom. Yet, like all spirituality, this is, in an unmediated manner, self-implicatory (Liebert 2002:30-49):14 by uttering the prayer, one is drawn into its created world (if a post-modern formulation may for a moment be allowed); the performative nature of the utterance is such that it draws the one who speaks it into its contents - paradoxically without having to say "I confess...".

Phenomenologically, this runs in close parallel to the nature of faith confessed by prominent strands of Judaism and Christianity that lie in the wake of the Sh'ma as much as in the wake of the religious identities constituted by the rest of the associated religious heritages: that faith is given, and never achieved; with this gift not as a reward, but offered freely, without a transactional prior act or orientation. Faith is such that it is not attained; it is simply found. It is as if one cannot believe; rather one is believed - in this sense only, that one finds oneself having been led into faith. Therefore, no pride or comparison or evaluation is ever possible - something fully acknowledged within spiritual direction, or better said, spiritual accompaniment.

Faith is, therefore, paradoxically, never self-affirming, in the modern populist self-help or power of positive thinking or television talk show varieties of what counts as "spirituality", yet always overwhelming - with "transformation" as a key experience (and hence a Leitwort in Spirituality scholarship; cf. Waaijman 2002:455-483 - also with other, roughly synonymous terms, for example in Human 2001:59, 62-63, 67-69).

This parallels prayer exactly, drawn from the Sh'ma directly: prayer is never an achievement; never a reward. Prayer is a response only in the sense that one finds oneself engaged in it; one finds oneself, somehow, prayed, or praying - again in this sense only, that one finds oneself at prayer; one finds oneself having been led into this act of faith. To formulate it in the almost blasphemously negative: no prayer - as with: no faith; as with: no humility - can be boastful. A display of arrogance would not mean the destruction of the prayer, faith or humility; more fundamentally, it would mean that that prayer, faith or humility had never existed; certainly not in any authentic way. There are no degrees of comparison when it comes to prayer/faith/humility.15

Echoing the Casanova/Petrarch epigraph above, Canadian singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen articulated it this way:

There's a blaze of light in every word

It doesn't matter which you heard

The holy or the broken hallelujah.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ap Siôn, T. 2010. An empirical study of ordinary prayer. Unpublished PhD thesis. Warwick: University of Warwick. [ Links ]

Avisar, S. 1985. Senso e struttura delle preghiere. La Rassegna Mensile di Israel (terza serie) 51(2):255-267. [ Links ]

Benson, I.T. & Bussey, B.W. 2017. Religion, liberty and the jurisdictional limits of law. Ottawa: LexisNexis Canada. [ Links ]

Biernot, D. & Lombaard, C. 2017. Religious experience in the current theological discussion and in the church pew. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 73(3):1-12. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 2002. Spirituality of the Psalms. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Brümmer, V. 2008. What are we doing when we pray? On prayer and the nature of faith. 2nd ed. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing. [ Links ]

Brümmer, V. 2011. Wat doen ons wanneer ons bid? Oor die aard van gebed en geloof. Wellington: Bybel-Media. [ Links ]

Casanova, J. 2014 [1894, translation of 1826 French text]. The memoirs of Jacques Casanova de Seingalt, 1725-1798. Adelaide: eBooks@Adelaide/The University of Adelaide Library. [ Links ]

Cooper, H. 2003. "Hear o Israel": The "impossible profession" of Jewish faith. European Judaism 36(1):81-90. [ Links ]

Dawkins, R. 1976. The selfish gene. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

De Beer, F. 1983. Eksistensiele kommunikasie. 'n Beknopte eksposisie van die kommunikasieteorie van Karl Jaspers (1883-1969). Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Wysbegeerte 2(3):161-169. [ Links ]

Eaton, J.H. 2004. Meditating on the Psalms. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Eaton, J.H. 2006. Psalms for life: Hearing and praying the book of Psalms. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Firth, D.G. 2005. Hear, o Lord. A spirituality of the Psalms. Calver: Cliff College Publishing. [ Links ]

Flanagan, K. & Jupp, P.C. (Eds) 2007. The sociology of spirituality. Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Gilbert, E. 2006. Eat, pray, love. One woman's search for everything across Italy, India and Indonesia. New York: Viking. [ Links ]

Giordan, G. & Woodhead, L. (Eds) 2013. Prayer in religion and spirituality. Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion 4. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Giordan, G. & Woodhead, L. 2015. A sociology of prayer. Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Human, D.J. 2001. Gebed: 'n Proses wat verandering bemiddel. Verbum et Ecclesia 22(1):58-71. [ Links ]

Hunziger, A. & Peng-Keller, S. 2014. Beten (Hermeneutische Blatter 2). Zurich: Institut für Hemeneutik & Religionsphilosophie, Theologische Fakultat, Universitat Zürich. [ Links ]

James, W. 2002 [1902]. The varieties of religious experience. A study in human nature. Philadelphia, PA: The Pennsylvania State University. [ Links ]

Janzen, J.G. 1987. On the most important word in the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4-5. Vetus Testamentum 37(3):280-300. [ Links ]

Jaspers, K. 1956a. Philosophie, Vol. II: Existenzerhellung. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. [ Links ]

Jaspers, K. 1956b. Reason and existenz. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Kloppers, M.H.O. 1989. Gebed in die Ou Testament. Acta Theologica 9(1-2):1-13. [ Links ]

Kraut, J. 2011. Deciphering the Shema: Staircase parallelism and the syntax of Deuteronomy 6:4. Vetus Testamentum 61:582-602. [ Links ]

Le Roux, J.H. 2001. No theory, no science (or: Abraham is only known through a theory). Old Testament Essays 14(3):444-457. [ Links ]

Liebert, E. 2002. The role of practice in the study of Christian Spirituality. Spiritus 2(1):30-49. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2006. Four recent books on spirituality and the Psalms: Some contextualising, analytical and evaluative remarks. Verbum et Ecclesia 27(3):909-929. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2011. Biblical Spirituality and interdisciplinarity: The discipline at cross-methodological intersection. Religion & Theology 18:211-225. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2015. "And never the twain shall meet"? Post-secularism as newly unfolding religio-cultural phase and Wisdom as ancient Israelite phenomenon. Spiritualities and implications compared and contrasted. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 152:82-95. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2018. "Sing unto the LORD a new song" (Ps. 98:1). Aspects of the Afrikaans punk-rock group Fokofpolisiekar's musical spirituality as rearticulated aspects of the 1978 Afrikaans Psalm- en Gesangeboek. In R. Hewitt & C. Kaunda (eds.), Who is an African? Engagement with issues of race, afro-ancestry, identity, and destiny within the South African context. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. Forthcoming. [ Links ]

McConville, J.G. 2013. Spiritual formation in the Psalms. In A.T. Lincoln, J.G. McConville & L.K. Pietersen (eds.), The Bible and spirituality. Exploratory essays in reading Scripture spiritually. (Eugene, OR: Cascade), pp. 56-74. [ Links ]

Miller, P.D. 1984. The most important word: The yoke of the kingdom. Iliff Review 41:17-29. [ Links ]

Muller, P. (Red.) 2016. Kom ons bid. Gebede vir vandag. 2de uitgawe. Pretoria: Malan Media. [ Links ]

Omartian, S. 1997. The power of a praying wife. Eugene, Or: Harvest House. [ Links ]

Otto, E. 2000. Das Deuteronomium im Pentateuch und Hexateuch. Studien zur Literaturgeschichte von Pentateuch und Hexateuch im Lichte des Deuteronomiumrahmens. (Forschungen zum Alten Testament 30.) Tubingen: J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck). [ Links ]

Otto, E. 2004. "Wer wenig im Leben hat, soll viel im Recht haben". Die kulturhistorische Bedeutung der Hebraischen Bibel fur eine moderne Sozialethik. In B. Levinson & and E. Otto (Hrsg.), Recht und Ethik im Alten Testament (Altes Testament und Moderne 13). (Munster: LIT Verlag), pp. 181-188. [ Links ]

Otto, E. 2012. Deuteronomium 1-11, Zweiter Teilband: 4,44-11,32 (Herders Theologischer Kommentar zum Alten Testament). Freiburg: Verlag Herder. [ Links ]

Otto, R. 1917. Das Heilige: Uber das Irrationale in der Idee des Gottlichen und sein Verhaltnis zum Rationalen. Breslau: Trewendt & Granier. [ Links ]

Otto, R. 1923. The idea of the holy: An inquiry into the non-rational factor in the idea of the divine and its relation to the rational. 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Rosa, H. 2013. Social acceleration: A new theory of modernity. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Reventlow, H.G. 1986. Gebet im Alten Testament. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer. [ Links ]

Schneiders, S. 2013. Biblical Spirituality: Text and transformation. In A.T. Lincoln, J.G. McConville & L.K. Pietersen (eds.), The Bible and spirituality. Exploratory essays in reading Scripture spiritually. (Eugene, OR: Cascade), pp. 128-150. [ Links ]

Stuhlmueller, C. 2002. The spirituality of the Psalms. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. [ Links ]

Veijola, T. 1992. Hore Israel! Der Sinn und Hintergrund von Deuteronomium VI 4-9. Vetus Testamentum 42(4):528-541. [ Links ]

Waaijman, K. 2002. Spirituality. Forms, foundations, methods. Dudley, MA: Peeters. [ Links ]

Waaijman, K. 2004. Mystiek in de psalmen. Baarn: Uitgeverij Ten Have. [ Links ]

Welzen, H. 2011. Contours of Biblical Spirituality as a discipline. In P.G.R. de Villiers & L.P. Pietersen (eds.), The Spirit that inspires: Perspectives on Biblical Spirituality (Acta Theologica Supplementum 15). (Bloemfontein: SUN MeDIA), pp. 37-60. [ Links ]

Westermann, C. 1978. Grundformen prophetischer Rede. München: Kaiser Verlag. [ Links ]

Wilkinson, B.H. 2000. The prayer of Jabez: Breaking through to the blessed life. Sisters, OR: Multnomah. [ Links ]

Zahavy, T. 1989. Political and social dimensions in the formation of early Jewish prayer: The case of the Shema'. Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (Volume I: Jewish thought and literature), pp. 33-40. [ Links ]

1 Paper read at "Pray without ceasing" Conference, Kloster Kappel conference centre/Center for the Academic Study of Christian Spirituality, University of Zurich, 26-29 June 2017.

2 Translation: [Prayer is] with the knees of the mind genuflected (Casanova 2014 [1894/1826]: Kindle edition, quoting Petrarch (14 century).

3 For an overview, cf. Welzen 2011:37-60; on the methodological difficulties, cf. Lombaard 2011:211-225.

4 Translation: Prayer as a spontaneous cry in moments of anguish is as universal and ancient as humanity. Prayer as a religious institution, as a daily rite and public manifestation, is an invention of Judaism. This form of prayer was born, it can be assumed, after the destruction of the First Temple, but has been fully developed and consolidated, imposing itself as one of the foundations of Jewish life after the fall of the Second Temple. The house of prayer was not tied to a certain place, but whenever a Jewish community was established, it acquired, over time, an extraordinary spiritual power; and the prayers assumed functions and meanings beyond those of sacrificial worship. Public prayers are one of the great contributions of Judaism to human civilization...

5 Translation: Here the reference is not to an expectant silence so as the other may speak or to an uncomfortable silence of mistrust, or to a sympathetic silence that shows compassion, or to an empty silence in which nobody has anything to say, but to the fullest of silences which confirm the inadequacy of every (any) language, and which is more eloquent than words.

6 Source: www.reverendfun.com/toon/20010817.

7 Kraut 2011:484 (cf. Veijola 1992:529-530) lists the standard variations of translation as:

(i) "YHWH is our God, YHWH alone";

(ii) "YHWH is our God; YHWH is one";

(iii) "YHWH our God, YHWH is one";

(iv) "YHWH our God is one YHWH".

The understanding of these possibilities vary between monolatry (or, unlikely, monotheism/monojahwism) and the unity of God (as opposed to polytheism or later, anomalously, trinitarianism) - cf. Veijola 1992:528-529, 535-536; or as Janzen 1987:280 finely groups the interpretations of "the word says something about Israel's God in se (Yahweh is 'one, unique', or the like); or it says something about the claim of this God upon Israel ('Yahweh is our God, Yahweh alone', or the like)". As Otto (2012:721-722) states: "Die Einzigkeit JHWHs, dem die ungeteilte Loyalitát gelten soll und von dem alles komme, was von einem Gott zu erwarten sei, ist das gemeinsame Thema des Schem' Israel und des Loyalitátsgebots in Dtn 13, 2-12*."

Kraut's own translation (2011:593), reading the repetition of YHWH as a poetic-stylistic figure of staircase parallelism - which would fit well with the initially epithetic and later aphoristic nature of this confession - renders a plausible "YHWH our God is one". This would imply, "YHWH is our only God", which links purposefully and, theologically speaking importantly with the first commandment (Veijola 1992:534) and with Deuteronomy 13, as Otto (2012:722) points out.

8 Translation: different viewpoints and emphases on this communion-experience between humans and God.

9 In this instance, by "earlier" is meant historically preceding (thus not what might seem the more obvious intent, the texts from three books ago in the Pentateuch).

10 Janzen (1987:282) argues this point only halfway.

11 One notes the attempts at disentangling this link in, for instance, the theology of Paul and that of Luther. In South African Calvinist circles, one observes this struggle in widespread formulation attempts among church ministers, such as that grace constitutes not freedom from law, but unto law.

12 In a somewhat esoterically inclined contribution, and not considering any of the theological lines in the preceding paragraphs, Cooper (2003:82) asks philosophically, does the perplexing formulation of the Sh'ma not in some way point "towards an appreciation of certain ambiguities and uncertainties that emanate from the very notion of God's existence?"

13 The poetic formulation in Deuteronomy 6:6-9, "And these words that I command you today shall be on your heart. You shall teach them diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise. You shall bind them as a sign on your hand, and they shall be as frontlets between your eyes. You shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates" may freely be given in summary as "at all times", with Deuteronomy 26:16-17 (Otto 2012:785), which puts the same idea in another way: "This day the LORD your God commands you to do these statutes and rules. You shall therefore be careful to do them with all your heart and with all your soul. You have declared today that the LORD is your God, and that you will walk in his ways, and keep his statutes and his commandments and his rules, and will obey his voice."

14 Various rhetorical techniques in the book of Deuteronomy do this, continually.

15 There are many humorous anecdotes about believers competing with one another on their "levels" of humility: who is the most humble? All of these stories make the point precisely: competition in humility of itself destroys the very essence of humility. The common quip by obstetricians that one is "a little bit pregnant" demonstrates this in one way; that famous witticism by Mark Twain that "The report of my death was an exaggeration" shows the same in another manner. With humility there are no grades. The exact same applies to faith and to prayer: such acts have a certain phenomenological absoluteness about them, which characteristically defies evaluation in any positivist or objectivist sense.