Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Theologica

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.38 no.1 Bloemfontein 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v38i1.5

ARTICLES

In search of the origins of Israelite aniconism

S.I. Kang

Associate Professor, Yonsei University, Wonju, South Korea. E-mail: seungilkang@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

For a long time, aniconism has been presented as one of the most distinctive characteristics of the religion of ancient Israel. Aniconism refers to the absence or repudiation of divine images. Such a tradition was inconceivable to Israel's neighbours, where the care, feeding, and clothing of a deity, represented in the form of a divine statue, played a central role in national cults (Jacobsen 1987:15-32; Berlejung 1997:45-72; Walker & Dick 2001; Roth 1992:113-147; Roth 1993:57-79). The issue of aniconism has, therefore, been the subject of much scholarly debate. In discussing the concept of aniconism, this article follows Mettinger's (1995:18) distinction between de facto aniconism (the mere absence of iconic representations of a deity) and programmatic aniconism (the repudiation of such representations). Many theories on the origins of the strong aniconic tradition in Yahwism have been put forward. Some major theories will be critically reviewed, and a new synthesis with reference to archaeological and iconographic data will be presented.

Keywords: Aniconism, Deuteronomist, Temple, Yahweh's cult statue

Trefwoorde: Anakonisme, Deuteronomis, Tempel, Jahweh se kultus standbeeld

1. TRADITIONAL THEORIES

There are four major traditional lines of thought concerning the origins of aniconism in ancient Israel. First, compared to other ancient Near-Eastern deities, who were associated with natural phenomena, Yahweh was conceived as a god of history, and so could not be represented in a physical form (Zimmerli 1963:234-248). Secondly, the God of Israel cannot be manipulated by magic; so, producing divine statues of Him, normally used for said manipulation, is moot (Zimmerli 1963:234-248). Thirdly, the transcendent nature of Yahweh distinguishes Him from other deities, and leads to the avoidance of depicting Him (von Rad 1962:218). Fourthly, the repudiation of images is meant to contrast Yahweh with other Canaanite deities (Keel 1977:37-45; Dohmen 1985:237-244).

Hendel (1988:368-372) carefully examined and criticized these four theories. In addition to his evaluation, the following may be added. All the traditional positions are based on the common idea that aniconism arose as one of the most distinctive features of Yahwism in the process of differentiating the religion of Israel from those of its neighbours. However, Israel and its surrounding cultures shared a common heritage in many social and religious aspects. In particular, the de facto aniconism in Israel, as attested to by the cult of masseboth, especially at the Arad temple, seems to be a continuation of the West Semitic masseboth cult (Mettinger 1995). Therefore, theories reliant on the old paradigm of distinction from surrounding cultures no longer hold water.

2. RECENT THEORIES

2.1 Bias against kingship

Hendel (1988:378-382) proposed the interesting idea that Israel's aniconic tradition may be ascribed to its peculiar bias against kingship. Kings in the ancient Near East were thought to be manifestations or adopted sons of deities. However, it seems that the society of ancient Israel harboured an anti-kingship sentiment; as Yahweh was their king, the Israelites disavowed human kingship. This is evident in the Deuteronomistic History. In early Israel, kings were under prophetic authority, as exemplified by the story of Samuel anointing David as a new leader (1 Sam. 16). While God was considered to have control over kingship, His prophets exercised authority on His behalf. In fact, many prophets opposed evil kings, especially in the northern kingdom, and heavily criticized them when they failed to follow the Lord. It has, therefore, been suggested that the Deuteronomistic History has an underlying prophetic stratum (McCarter 1984:6-8). As kings were earthly representatives of deities, they could be restrained by removing depictions of the deity. According to Hendel, this is how Israel's aniconic tradition may have originated from its deep-rooted bias against kingship.

However ingenious his proposal may be, it is not without problems. First, as discussed earlier, Israel's anti-kingship sentiment is largely a literary phenomenon, specifically, of the so-called Prophetic History underlying the Deuteronomistic History, which attempted to defame the monarchy in the northern kingdom and to show its subjection to prophecy. One must thus be cautious not to take the anti-kingship sentiments reflected in this literary work at face value. Moreover, it is unlikely that a mere literary phenomenon could lead directly to the actual elimination of cult images.

Many royal psalms (Pss. 2, 18, 20, 21, 45, 72, 89, 110, and so on) attest to the idea of the king as God's adopted son in ancient Israel.

I have set my king upon Zion, my holy mountain.

I will tell of the decree of the Lord.

He said to me: "You are my son.

Today I have begotten you.

Ask of me, and I will give the nations for your inheritance,

and the ends of the earth for your possession." (Ps. 2:6-8).He shall cry to me: "You are my Father,

my God, and the rock of my salvation."

I will make him the firstborn,

the highest of the kings of the earth (Ps. 89:26-27).

Intriguingly, God calls the king his son in these psalms, stating that He has begotten the king. Similarly, in a message to Nathan for David with reference to David's future son, God said, "I will be a father to him, and he shall be a son to me" (2 Sam. 7:14). Such language unmistakably demonstrates that Israel shared with its neighbours the concept of divine kingship.1

If, as Hendel argues, there was a strong bias against the institution of kingship in Israel, what would explain the pro-kingship sentiment expressed in these psalms? It is clear that this attempt to explicate the origins of aniconism based on a literary formulation of anti-kingship bias limited to the Deuteronomistic History cannot prevail.

2.2 Mesopotamian influence

Ornan's argument is in marked contrast to Hendel's. She asserts that divine emblems and symbols replaced anthropomorphic representations of divinities, except within the sacred space of the temple in the first half of the first millennium in Mesopotamia (Ornan 2005). She explains this movement towards non-anthropomorphism as motivated by the need for the exaltation of the king; with the removal of the human-shaped deity from the walls of the palace, the king would become the centre of attention (Ornan 2005:15). Ornan suggests that this trend ultimately influenced the aniconic tradition in Israel. Mettinger (1995:55-56) points to the possibility that the aniconic character of the Ashur cult may also have been a catalyst for Yahwistic aniconism. These theories contrast the popular idea that Israel's aniconic tradition arose from its antipathy towards the Mesopotamian religions, characterized by the cult of images.

However, these explanations are unconvincing. For most of the periods in the long history of ancient Mesopotamia, the typical mode of representation of divinities was anthropomorphic. The exceptional cases of eschewing anthropomorphic images of deities in the first millennium may be ascribed to a fear of desecration by handling divine statues or figures without due care. Moreover, as anthropomorphic cult statues of major deities were still consistently used inside temples, the Mesopotamian religion was basically iconic. It should also be noted that, while divine emblems and symbols substituted for anthropomorphic images of deities in Mesopotamia, Yahweh in Israel was never fully represented by an emblem or a symbol. Moreover, if, as Ornan argues, the move towards non-anthropomorphism was intended to exalt the king at the expense of deities, such a tradition would have had no place in Israelite theology, where the idea of the king contending with Yahweh for power was unthinkable.

Finally, the Ashur cult Mettinger mentioned cannot be evidence for Assyrian aniconism either. There are many symbols of Ashur, such as the winged disc, and the common representations of him are often accompanied by his emblem.2 Most of the time, Ashur is not presented by the emblem alone, but by a human-shaped figure of the god within the winged disc (Keel 1997:fig. 295, 296). Therefore, the cult of Ashur was not aniconic, and thus cannot be taken to have influenced the image ban in Israel.

2.3 Reforms of Hezekiah and Josiah

Evans attempted to locate the root of Israelite aniconism in internal political developments, rather than external influences. Evans (1995:192212) points out the case of Jeroboam's gold calves. According to him, it was common to associate Yahweh with the bull or calf in Israel. The twelve bulls supporting the huge water basin called "the Sea" in Solomon's Temple, as well as biblical evidence such as Genesis 49:24, Exodus 32, and Numbers 23:22; 24:8, point to this association.3

According to Evans, Israelite aniconism had a sociopolitical cause, rather than a religious one. The northern refugees who came to Jerusalem after the fall of Samaria brought with them the idea of representing Yahweh with bull imagery. The Deuteronomist theologians eagerly rebuked the golden calves and turned Jeroboam into an archenemy of Yahwistic faith, lest the bull imagery should supplant Yahweh on the cherub throne in the Temple in Jerusalem in the mind of the people. In this process, the repudiation of the use of images for Yahweh became a central theological concept of the reform programmes of Hezekiah and Josiah, who wanted to remove local high places and centralize the worship of Yahweh.

Despite its merits of attributing the origins of Israelite aniconism to internal sociopolitical causes, Evans' theory has weaknesses as well. It does not consider many archaeological and iconographic materials that may shed light on the question of aniconism in Israel, such as the masseboth and the Kuntillet 'Ajrud inscriptions referring to "Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah", to name a few. Moreover, the historicity of the reforms of those kings, especially Hezekiah, is seriously questionable (Na'aman 1995:179-195; Fried 2002:437-465; Edelman 2008:395-434).

3. THE ORIGINS OF ISRAELITE ANICONISM

Having reviewed some of the major theories, old and new, on the origins of aniconism in ancient Israel, let us now address the question with a synthesis of both archaeological and textual evidence.

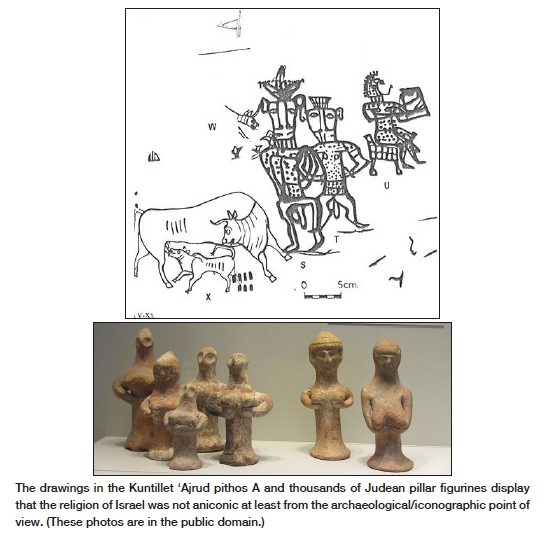

Archaeological and epigraphic data are important, because material culture can help us reconstruct the religious reality of an ancient society. Considering only the biblical records, one may conclude that aniconism was the norm in the Yahwistic religion. The archaeological and epigraphic evidence says otherwise. Iron-Age Israel was replete with icons and images, as evidenced by the bronze bull figurine from the Bull Site, the famous "Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah" inscription from Kuntillet 'Ajrud, thousands of Judean pillar figurines, numerous seals and bullae with images of deities, and the Taanach cult stand embellished with various icons of the sun disc, a calf or horse figure, Asherah, lions, cherubim, and so forth.

Eminent American archaeologist William Dever (1983:574) once firmly stated as follows:

No representations of a male deity in terra cotta, metal, or stone have ever been found in clear Iron Age contexts, except possibly for an El statuette in bronze from 12th-century Hazor and a depiction of an El-like stick figure on a miniature chalk altar from 10th-century Gezer, and neither is necessarily Israelite.

The situation has changed since that statement. Though a controversial conclusion, it seems likely that the drawings with the inscription in the Kuntillet 'Ajrud pithos A represent Yahweh and his consort.4

In addition, Uehlinger (1997:149-152) suggests that the so-called Munich terracotta figurine from Tell Beit Mirsim from the late 8th or early 7th century BCE may represent Yahweh and his consort Asherah sitting or standing on what appears to be a throne. Because of its damaged condition and lack of detail, one cannot be certain about this, but it is encouraging that there are more candidates for the image of Yahweh. What is emerging from the archaeological and epigraphic evidence from Iron-Age Israel is far from an aniconic religion, contrary to the biblical notion that the Israelites never venerated Yahweh or other deities in a visual form.

One may still argue that anthropomorphic representations of a male deity in Israel are few and far between. This may be because the Israelites allowed anthropomorphic images of Yahweh only in the Jerusalem Temple. In other words, there may have been a cult statue of Yahweh in the holy of holies of Solomon's Temple. Niehr (1997:73-95) has convincingly demonstrated that there was indeed a Yahweh cult statue in the First Temple.5 Uehlinger (1997:149-152) goes further in suggesting that there was also a cult statue of Asherah in the First Temple.

A similar situation existed in the first-millennium Mesopotamia, where the opening of the mouth ritual was practised on the anthropomorphic cult statue of the deity in the temple, to which meals were offered regularly twice a day (Jacobsen 1987:15-32; Lambert 1993:191-203; Berlejung 1997:45-72; Walker & Dick 1999:55-121). The existence of such a statue in the temple is certain. However, human-shaped statues or images of divinities were extremely rare outside the national sanctuary. As noted earlier, divine emblems and symbols supplanted anthropomorphic images in these instances.

This phenomenon may be explained by the need for maintaining the sacredness of the divine statue. Installing it within the temple is not a problem, because it would be under the priests' control. In other places, however, proper care and handling of the statue cannot be guaranteed. This is supported by the observation that the second commandment, pertaining to the image ban, is followed by the third commandment, which concerns the wrongful use of the name of the Lord (Exod. 20:7; Deut. 5:11). This indicates that the prohibition of divine images may have been influenced by the desire to prevent their mistreatment. Another contributing factor may have been the priests' concern about a decrease in their power at the Temple in Jerusalem, if local sanctuaries were allowed to use divine images for their own cult, thus encouraging independence.

While the cumulative archaeological and epigraphic data indicate the iconic character of the religion of Israel (Keel 1977; Keel 1998; Keel & Uehlinger 1998; Cornelius 2004; Van der Toorn 1997). It should be noted that there existed a simultaneous tendency towards de facto aniconism. Evidence for this comes from the masseboth cult. Many scholars believe that the masseboth or the standing stones could represent a deity without a specific physical description. We know from the Bible that standing stones could function in many different ways: the stone Jacob set up with Laban was a kind of boundary stone (Gen. 31); the twelve stones Moses set up represented the twelve tribes of Israel (Exod. 24), and Absalom erected a stone as a surrogate for an heir (2 Sam. 18). Yet some biblical passages attest to the cultic usage of the masseboth, sometimes representing deities (Gen. 35:14; Exod. 23:24; Lev. 26:1; Deut. 16:21-22; 2 Kings 3:2; 10:26-27; 23:14; Isa. 19:19; Hos. 3:4).

Mettinger (1995:167) performed a thorough analysis of standing stones found at many archaeological sites in Palestine, including Arad, Lachish, Beth Shemesh, the "Bull Site", Tirzah, Megiddo, Taanach, and Tell Dan, and concluded that "the masseboth were aniconic representations of the deity". His methodology and conclusion invited heavy criticism, mainly because he regarded the majority of masseboth as cultic without proper scrutiny.6Bloch-Smith (2005:28-39; 2006:64-79) re-evaluated the masseboth and attempted to determine their exact function in context. Establishing her own set of criteria for the identification of cultic masseboth, she applied them to the masseboth found at major excavation sites. According to her analysis, the majority of masseboth turned out to be non-cultic, having been set up with some functional purpose, or as structural elements. Nonetheless, she acknowledged the cultic character of the masseboth from at least one site, Arad. In other words, the masseboth at the Arad temple may be considered to be aniconic representations of a deity or deities.7

According to Mettinger (1995:195-196), the roots of this phenomenon, which may be called de facto aniconism, are found in the West-Semitic masseboth cult. He argued that the programmatic aniconism or iconoclasm in Israel was a development from West-Semitic aniconic traditions, characterized by the masseboth cult. Such a sweeping argument, however, is hard to support. An isolated phenomenon such as the masseboth cult at Arad cannot explain the emergence of the image ban as attested in the Bible, though it must be said that Mettinger's conclusion arose from his belief that the masseboth at many other sites were also cultic.

I believe that the explicit prohibition against divine images is largely a Deuteronomist literary phenomenon. The most frequently cited evidence relating to the ban on images comprises the Second Commandment of the Decalogue (Exod. 20:23, 34:17; Lev. 19:4, 26:1; Deut. 4:15-19). Contrary to the common view that the Bible outright condemns the production of images of Yahweh, none of these citations, in fact, addresses images of Yahweh per se. If read carefully, they merely warn against making idols of foreign gods and goddesses (Exod. 20:23; 34:17; Lev. 19:4; 26:1). The Second Commandment and Deuteronomy 4 speak of a general image ban, but not against images of Yahweh specifically, but against making images meant for the worship of anything besides God.

While Dohmen (1985:154-180, 262-273) claimed that the biblical passages concerning iconoclasm, except for Exodus 20:23, came from the time of Deuteronomy or later, studies have shown that even the final version of the Decalogue was edited and inserted into the current context by an exilic Deuteronomist editor (Nicholson 1977:422-433). Indeed, the Decalogue in both Exodus and Deuteronomy is full of Deuteronomist language. In particular, the combination of the Hebrew terms  and

and  appears only in the Second Commandment, apart from Deuteronomy (4:16, 23, 25), which exhibits the connection between the Second Commandment and Deuteronomy (Blenkinsopp 1992:207ff.). The following episodes in the Deuteronomist works may also indicate the concept of aniconism: people heard the voice of the Lord, but saw no form (Deut. 4:10-13, 5:22);8 Dagon had fallen before the ark of the Lord (1 Sam. 5), and Elijah did not see God in the wind, earthquake, fire, but only heard His voice (1 Kings 19).

appears only in the Second Commandment, apart from Deuteronomy (4:16, 23, 25), which exhibits the connection between the Second Commandment and Deuteronomy (Blenkinsopp 1992:207ff.). The following episodes in the Deuteronomist works may also indicate the concept of aniconism: people heard the voice of the Lord, but saw no form (Deut. 4:10-13, 5:22);8 Dagon had fallen before the ark of the Lord (1 Sam. 5), and Elijah did not see God in the wind, earthquake, fire, but only heard His voice (1 Kings 19).

What, then, is the true origin of the biblical prohibition on images, even if not specifically the image of Yahweh, as attested in works from the time of Deuteronomy and thereafter? Various factors may have contributed to the development of programmatic aniconism. The aniconic masseboth cult at Arad may have been one such factor. In terms of iconographic evidence, a shift from iconic to aniconic seals took place, mainly due to the spread of literacy from the seventh century BCE (Sass 1993:243ff.).

However, the most significant incident to the course of the religion of Israel was the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple by the Babylonians.9 In order to explain this catastrophic event, the Deuteronomist theologians attempted to transform the nature of Yahwism from monolatry to monotheism, because, from the perspective of monolatry, the fall of Judah would have meant that the God of Israel was weaker than Marduk. In the monotheistic point of view, however, Yahweh becomes the god of the universe who uses the Babylonians as a tool to punish His own people.

With the loss of the statue of Yahweh inside the Temple, a new theology to cope with the situation was formulated. Since it was no longer possible to maintain the worship and rituals that centred on the cult statue, the new line of theology rejected divine images altogether.10 This theology was better suited to account for a god who resided in the heavens, was transcendent, and was not limited to a specific form; this also meant that any images said to represent him were by necessity fake.

Secondly, Isaiah partook in this endeavour by proclaiming Yahweh as the only true god of the universe, repudiating representations of deities, and deriding foreign idols (Isa. 40:18-25, 41:29, 44:1-20).

To whom will you liken God?

Or what likeness will you compare with him?

An idol?A workman melts it,

and a goldsmith overlays it with gold

and casts silver chains for it (Isa. 40:18-19).

In the meantime, the Deuteronomists and Ezekiel ventured to fill the vacuum created by the loss of the statue of Yahweh by substituting it with Yahweh's Name and His Glory (Kabod), respectively.

The loss of the divine image in the Temple demanded fundamental modification of the traditional theology. The representative Yahwistic groups and individuals, especially the Deuteronomist theologians, responded with the wholesale negation of images. Some scholars believe that the religion of Israel was aniconic from its incipient stage, but this is not true and only appears to be the case because of the Deuteronomist redaction of the Bible. The iconic character of the religion of Israel is supported by archaeological and iconographic data. It is likely that the programmatic aniconism of Yahwism is mainly a literary product of the Deuteronomist writers and editors coping with the destruction of the Temple, as it was only centuries later that it became normative in all strata of Israelite society.

4. SUMMARY

This article investigated the problem of the origins of Israelite aniconism. It critically reviewed various scholarly theories concerning the origins of aniconism and presented a new synthesis with reference to archaeological and iconographic data. Its main thesis was that the biblical prohibition on images is largely a creation of biblical authors after the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple by the Babylonians. Prior to that point, there had been Yahweh's cult statue in the Temple, and the exilic authors formulated a new theology to cope with the fact that they no longer had a statue of Yahweh.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berlejung, A. 1997. Washing the mouth: The consecration of divine images in Mesopotamia. In: K. van der Toorn (ed.), The image and the book: Iconic cults, aniconism, and the rise of book religion in Israel and the ancient Near East (Leuven: Peeters), pp. 45-72. [ Links ]

Black, J. & Green, A. 1992. Gods, demons and symbols of ancient Mesopotamia: An illustrated dictionary. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Blenkinsopp, J. 1992. The Pentateuch: An introduction to the first five books of the Bible. New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Block-Smith, E. 2005. Massebot in the Israelite cult: An argument for rendering implicit cultic criteria explicit. In: J. Day (ed.), Temple and worship in biblical Israel (London: T. & T. Clark), pp. 28-39. [ Links ]

Block-Smith, E. 2006. Will the real massebot please stand up: Cases of real and mistakenly identified standing stones in ancient Israel. In: G. Beckman & T.J. Lewis (eds.), Text, artifact, and image: Revealing ancient Israelite religion (Providence: Brown Judaic Studies), pp. 64-79. [ Links ]

Cornelius, I. 2004. The many faces of the goddess: The iconography of the Syro-Palestinian goddesses Anat, Astarte, Qedeshet, and Asherah c. 1500-1000 BCE. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [ Links ]

Day, J.(ed) 2013. King and Messiah in Israel and the ancient Near East. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Dever, W.G. 1983. Material remains and the cult in ancient Israel: An essay in archaeological systematics. In: C.L. Meyers & M. O'Connor (eds.), The word of the Lord shall go forth: Essays in honor of David Noel Freedman in celebration of his sixtieth birthday (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns), pp. 571-587. [ Links ]

Dever, W.G. 2005. Did God have a wife? Archaeology and folk religion in ancient Israel. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Dohmen, C. 1985. Das Bilderverbot: Seine Entstehung und seine Entwicklung im alten Testament. Bonn: Peter Hanstein. [ Links ]

Edelman, D. 2008. Hezekiah's alleged cultic centralization. Journal for the Study of Old Testament 32:395-434. [ Links ]

Evans, CD. 1995. Cult images, royal policies and the origins of aniconism. In: S.W. Holloway & L.K. Handy (eds.), The pitcher is broken: Memorial essays for Gösta W. Ahlström (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press), pp. 192-212. [ Links ]

Feder, Y. 2013. The aniconic tradition, Deuteronomy 4, and the politics of Israelite identity. Journal of Biblical Literature 132:251-274. [ Links ]

Fried, L.S. 2002. The high places (Bamot) and the reforms of Hezekiah and Josiah: An archaeological investigation. Journal of the American Oriental Society 122:437-465. [ Links ]

Hadley, J.M. 2000. The cult of Asherah in ancient Israel and Judah: Evidence for a Hebrew goddess. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hendel, R.S. 1988. The social origins of the aniconic tradition in early Israel. Catholic Biblical Quarterly 50:365-382. [ Links ]

Herring, S.L. 2013. Divine substitution: Humanity as the manifestation of deity in the Hebrew Bible and the ancient Near East. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [ Links ]

Jacobsen, T. 1987. The graven image. In: P.D. Miller, P.D. Hanson & S.D. McBride (eds.), Ancient Israelite religion: Essays in honor of Frank Moore Cross (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press), pp. 15-32. [ Links ]

Kang, S.I. 2008. "The molten sea", or is it? Biblica 89(1):101-103. [ Links ]

Keel, O. 1977. Jahwe-Visionen und Siegelkunst: Eine neue Deutung der Majestàts-schilderungen in Jes 6, Ez 1 und 10 und Sach 4. Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk. [ Links ]

Keel, O. 1997. The symbolism of the biblical world: Ancient Near Eastern iconography and the book of Psalms. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Keel, O. 1998. Goddesses and trees, new moon and Yahweh: Ancient Near Eastern art and the Hebrew Bible. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Series, Volume 261. [ Links ]

Keel. O. & Uehlinger, C. 1998. Gods, goddesses, and images of God in ancient Israel. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress. [ Links ]

Lambert, W.G. 1993. Donations of food and drink to the Gods in ancient Mesopotamia. In: J. Quaegebeur (ed.), Ritual and sacrifice in the ancient Near East (Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters), pp. 191-203 [ Links ]

Lewis, T.J. 1998. Divine images and aniconism in ancient Israel. Journal of the American Oriental Society 118: 36-53. [ Links ]

McCarter, P.K. 1980. 1 Samuel. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. Anchor Bible, Volume 8. [ Links ]

McCarter, P.K. 1984. 2 Samuel. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. Anchor Bible, Volume 9. [ Links ]

McCarter, P.K. 1987. Aspects of the religion of the Israelite monarchy: Biblical and epigraphic data. In: P.D. Miller, P.D. Hanson & S.D. McBride (eds.), Ancient Israelite religion: Essays in honor of Frank Moore Cross (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press), pp. 137-155; [ Links ]

Meshel, Z. 1979. Did Yahweh have a consort? The new religious inscriptions from the Sinai. Biblical Archaeology Review 5(2):24-35. [ Links ]

Mettinger, T.N.D. 1995. No graven image? Israelite aniconism in its ancient Near Eastern context. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. [ Links ]

Na'Aman, N. 1995. The debated historicity of Hezekiah's reform in the light of historical and archaeological research. Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 107:179-195. [ Links ]

Nicholson, E.W. 1977. The Decalogue as the direct address of God. VT 27:422-433. [ Links ]

NIehr, H. 1997. In search of YHWH's cult statue in the first Temple. In: K. van der Toorn (ed.), The image and the book: Iconic cults, aniconism, and the rise of book religion in Israel and the ancient Near East (Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters), pp. 73-95. [ Links ]

Olyan, S.M. 1988. Asherah and the cult of Yahweh in Israel. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press. [ Links ]

Ornan, T. 2005. The triumph of the symbol: Pictorial representation of deities in Mesopotamia and the biblical image ban. Fribourg: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Romer, T.C. 2007. The so-called Deuteronomistic History: A sociological, historical and literary introduction. London: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

Roth, A.M. 1992. The pss-kf and the "opening of the mouth" ceremony: A ritual of birth and rebirth. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 78:113-147. [ Links ]

Roth, A.M. 1993. Fingers, stars, and the opening of the mouth: The nature and function of the ntrwj blades. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 79:57-79. [ Links ]

Roth, A.M. 2001. Opening of the mouth. In: D.B. Redford (ed.), The Oxford encyclopaedia of ancient Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 606-608. [ Links ]

Sass, B. 1993. The pre-exilic Hebrew seals: Iconism vs. aniconism. In: B. Sass & C. Uehlinger (eds.), Studies in the iconography of northwest Semitic inscribed seals (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), pp. 194-256. [ Links ]

Uehlinger, C. 1997. Anthropomorphic cult statuary in Iron Age Palestine and the search for Yahweh's cult images. In: K. van der Toorn (ed.), The image and the book: Iconic cults, aniconism, and the rise of book religion in Israel and the ancient Near East (Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters), pp. 97-155. [ Links ]

Von Rad, G. 1962. Old Testament theology. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd. [ Links ]

Walker, C. & Dick, M.B. 1999. The induction of the cult image in ancient Mesopotamia: The Mesopotamian mïs-pi ritual. In: M.B. Dick (ed.), Born in heaven, made on earth: The making of the cult image in the ancient Near East (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns), pp. 55-121. [ Links ]

Walker, C. & Dick, M.B. 2001. The induction of the cult image in ancient Mesopotamia: The Mesopotamian mis pi ritual. Helsinki: The University of Helsinki. [ Links ]

Zimmerli, W. 1963. Das Zweite Gebot. In: Gottes Offenbarung: Gesammelte Aufsãtze zum Alten Testament (Munich: Chr. Kaiser Verlag), pp. 234-248. [ Links ]

1 For divine kingship in Israel and the ancient Near East, see Day (2013); for the Mesopotamian concept of the king as adopted son of a god, see Herring (2013:38ff.).

2 The winged disc, which is usually believed to be associated with Ashur, may originally have belonged to the sun god Shamash (Black & Green 1992:38).

3 For the interpretation of the name of the water basin, see Kang (2008:101-103).

4 Apart from various other possibilities of interpreting the expression 'šrth, such as "asherah of it (= Samaria)", "his sanctuary", "his asherah (as a cult symbol)" as opposed to "his Asherah", the major opposition to the identification of the figure with Yahweh is to see it as representing the Egyptian god Bes. However, Bes was depicted typically as a grotesque dwarf with a large face usually in a squatting position, which can be easily distinguished from the bovine figures on the Kuntillet 'Ajrud. Therefore, notwithstanding the ambiguity about the interpretation of the expression 'šrth, it is likely that this is a portrayal of Yahweh as worshipped in Samaria. Of the vast bibliography on the Kuntillet 'Ajrud inscriptions, only a small selection can be presented in this instance (Meshel 1979:24-35; McCarter 1987:137-155; Olyan 1988; Hadley 2000; Dever 2005).

5 To the biblical and extra-biblical evidence Niehr collected, the following may be added: (1) There seem to be some traces of the mouth-opening ritual in the Old Testament (Isa. 6; Ps. 51) and some prophets were, in fact, familiar with the Mesopotamian ritual (Isa. 44:14; Jer. 10); (2) The reference to the "form of Yahweh" (Num. 12:8) and to the images of "Jerusalem and Samaria" (Isa. 10:10-11) may be an indication of the presence of a statue of Yahweh; (3) It is clear that the image of Asherah was set in the Jerusalem Temple (2 Kings 21:7); it would thus follow that an image of Yahweh, Asherah's consort, would also have been in the Temple, although the Bible does not preserve such an explicit reference, which may have been deleted by an editor; (4) Solomon's Temple was basically iconic, embellished with various motifs such as twelve oxen, pomegranates, cherubim, lions, and palm trees (1 Kings 7).

6 See the excellent review article of Mettinger's book by Lewis (1998:36-53).

7 Lewis (1998:50) observes that a society does not have to be completely iconic or aniconic. Aniconism can coexist with iconic traditions.

8 Römer recently argued that there are three main editions within the Deute-ronomistic History (Neo-Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian, and Persian). While ascribing Deuteronomy 4 to the Persian period, he suggested that this text may be a "polemic against a statue of Yahweh that probably stood in the Jerusalem temple during the monarchy" (Römer 2007:173). It seems to me, however, that there was no need for such a polemic during the Persian period when the cult statue of Yahweh no longer existed. Rather, the aniconic concept found in the Deuteronomistic History may have developed in the exilic period as a response to the loss of Yahweh's cult statue with the destruction of the Temple, which may weaken Römer's theory of a three-stage development of the Deuteronomistic History.

9 Both Feder (2013:272) and Uehlinger (1997:154-155) identify the exilic period as the background of the development of the image ban.

10 It appears that rituals similar to Mesopotamian counterparts have been performed in ancient Israel, such as the mouth-opening ritual (Isa. 6; Ps. 51) and the procession of divine images (2 Sam. 6; Ps. 24, 68, 132).