Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.37 n.2 Bloemfontein 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v37i2.7

ARTICLES

Prof. M.J. Nel

Department of Old and New Testament, Stellenbosch University. E-mail: mjnel@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article focuses on rituals in the Gospel of Matthew that affect forgiveness between God and human beings, as well as between human agents. It argues that rituals play an important role in signalling and affecting forgiveness. It gives an operational definition of a ritual and identifies possible atonement rituals in the Gospel of Matthew up to the crucifixion of Jesus. These rituals are analysed to determine how they affect atonement through the forgiveness of sins. Since access to these rituals is only possible through the text of Matthew, Strecker's taxonomy of how rites and text are interwoven in the New Testament is used to order the analysis of Matthew. Finally, concluding remarks are made on the relationship between ritual and authority in Matthew.

Keywords: The Gospel according to Matthew; Forgiveness; Ritual

Trefwoorde: Die Evangelie volgens Matteus; Vergifnis; Ritueel

1. INTRODUCTION

This article investigates the Matthean atonement rituals. Its focus on rituals that affect forgiveness between God and human beings, as well as between human agents is important, since the Gospel of Matthew recounts both the explicit teaching1 of the Matthean Jesus thereon as well as various actions and pronouncements of Jesus (and others), which claim to affect forgiveness.2 The article argues that, while not all attempted enactments of forgiveness are necessarily rituals,3 some rituals do play an important role in signalling and affecting forgiveness. Since rituals not only maintain existing power structures, but can also be transformative and innovative (for example, the Lord's Supper, which, in Matthew, reinterprets the Passover meal) (Klingbeil 2007:15), the article investigates the nature of the relationship between the Matthean atonement rituals and the different agents and structures that enacted forgiveness in the context of Matthew.

This article focuses on the ministry of Jesus up to his crucifixion. It will begin by giving an operational definition of a ritual, after which possible atonement rituals in the Gospel of Matthew will be identified and briefly analysed, in order to determine how they affect atonement through the forgiveness of sins. Since access to these rituals is only possible through the text of Matthew, Strecker's (1999:78-80) taxonomy of how rites and text are interwoven in the New Testament will be used to order the analysis of Matthew. Finally, concluding remarks will be made on the relationship between ritual and authority in Matthew.

2. RITUAL - DEFINITION AND TAXONOMY

Defining what is understood by the term "ritual" is no easy task, as is evident from Grimes' (1995:5) remark that "[r]itual is the hardest religious phenomenon to capture in texts or comprehend by thinking". In light of this difficulty, this article will follow the example of Platvoet (1995:25) who opts to give an operational definition of ritual. Operational in that he does not claim universal validity or applicability for his definition. Instead, his definition is intended to be a hypothesis with heuristic qualities that can be tested, corrected, and even rejected. According to Platvoet (1995:41-42),

[r]ituals are ordered sequence[s] of stylized social behaviour that may be distinguished from ordinary interactions by altering its qualities which enable it to focus the attention of its audiences - its congregation as well as wider public - onto itself and cause them to perceive it as a special event, performed at a special place and/ or time, for a special occasion, and/or with a special message. It affects this using the appropriate, culturally specific, consonant complexes of polysemous core symbols, of which it enacts several redundant transformations by multimedia performance.

This description of ritual as exhibiting an "ordered sequence of stylized social behaviour" and as "altering its qualities" indicates that behaviour may be condensed, exaggerated, and made rhythmic in a ritual (in other words, it has a formulistic nature). The reference to "the attention of its audiences" (plural) emphasises that it is not always performed for a homogeneous community and, therefore, does not always communicate with "insiders" by speaking a pre-agreed language (Klingbeil 2007:15). Rituals can also speak to "outsiders".4 It is also important to note that the elements of "special space, time, and message of rituals" serve to indicate that something out of the ordinary is occurring (Klingbeil 2007:18). The "core symbols" are the basic building blocks of ritual performance. A symbol can be defined as "any physical, social, or cultural act or object that serves as a vehicle for conception" (Geertz [1973] 2009:208) or as "an entity which stands for and represents another entity" (Klingbeil 2007:20). It thus has a communicative and representative function. Symbols, unlike signs, are not created arbitrarily, but are rooted in general life experiences and are, therefore, culture-bound (Klingbeil 2007:20).

Platvoet's operational definition will be used to identify possible atonement rituals in Matthew by attempting to answer four questions of various texts:

a. Is there evidence of an ordered sequence of stylised social behaviour?

b. Have this behaviour's qualities been altered to focus the attention of its audiences?

c. Is it performed as a special event at a special place and/or time for a special occasion, and/or with a special message?

d. Does it make use of appropriate, culturally specific, consonant complexes of polysemous core symbols?

While not all four questions need to be positively answered for an act to be a ritual according to Platvoet, most of them need to be. An action, which does not meet the criteria presupposed by these questions, may instead be described as a rite or symbol. According to Klingbeil (2007:5), who utilises the definition of Platvoet, cult,5 ritual, subrite (or simply rite) and symbol, therefore, need to be defined in terms of their relationship to each other. A specific ritual (sacrificing an animal) may, for example, incorporate several subrites (washing or blood daubing) and multiple symbols (wearing white clothes or an unblemished sacrificial animal) when functioning within a larger cult. A subrite (or "rite") is a unit that occurs within diverse rituals with distinct dimensions and functions that need to be understood in terms of how they are integrated into a ritual (Klingbeil 2007:21).6

3. REFERENCES TO ATONEMENT RITUALS IN THE GOSPEL OF MATTHEW

In analysing the atonement rituals in the Gospel of Matthew, it is important to bear in mind that one does not have access to the rituals themselves. One only has the text of Matthew which refers to them. In this regard, Strecker (1999:78-80) identified six ways in which rites and text are interwoven in the New Testament:

a. A text includes instructions or commands for carrying out a rite (for example, imperatival language embedded in a ritual setting such as "Do this in remembrance of me" (1 Cor. 11:24)).

b. A text reports the execution of a rite (for example, Jesus' baptism in Mark 1:9-11).

c. A text concerns itself with the meaning, function, or implementation of a rite (for example, the debate on the significance of Sabbath observance, purification, and fasting in Mark 2:23-28; 7:1-23; 2:18-20).

d. A text stems directly from ritual use (for example, the Christological hymn of Phil. 2:6-11).

e. A text has a ritual function in, and of itself (for example, the greeting and benediction of Paul's letters - see Phil. 4:21-23).

f. A text is connected synecdochically with a rite in that it may echo, allude, or refer to a rite, even though the text may not be about a ritual per se (for example, the reference to libation in Phil. 2:17-18).

In the following section, Strecker's taxonomy will be combined with the theoretical frame provided by Platvoet's operational definition and Klingbeil's development thereof, in order to analyse the atonement rituals in Matthew.7 The various texts will be ordered according to four of Strecker's categories, since there are no clear examples of (e) and (f) among Matthew's atonement rituals.

3.1 Texts that include instructions or commands for carrying out a ritual

It is unclear if the Gospel of Matthew has examples of texts that include instructions on how to perform an atonement ritual. The first possibility to consider is Matthew 18:15-20, which deals with the situation where a brother had sinned against another, in that it mentions specific actions to be undertaken. The offended person must "go"  , "convince"

, "convince"  , "take along"

, "take along"  a brother, "tell"

a brother, "tell"  the congregation and "treat as a pagan and tax collector"

the congregation and "treat as a pagan and tax collector"  the offender, if he does not seek forgiveness. Contrary to Platvoet's definition of a ritual, none of these actions are stylised or linked to a specific time and place. Nor are there any symbols or symbolic actions clearly incorporated therein,8 as it is not clear that to treat an unrepentant sinner as a pagan and tax collector refers to the performance of a specific symbolic action. If it does, it would signal the offender's exclusion and, therefore, not be part of an atonement ritual.9 The first step in this process is to avoid an audience. Matthew 18:15-20 is thus best understood as a church (or community) rule consisting of five sentences in the style of casuistic law, which could either affect reconciliation or lead to the exclusion of the offenders from their community (Luz 2001:448).

the offender, if he does not seek forgiveness. Contrary to Platvoet's definition of a ritual, none of these actions are stylised or linked to a specific time and place. Nor are there any symbols or symbolic actions clearly incorporated therein,8 as it is not clear that to treat an unrepentant sinner as a pagan and tax collector refers to the performance of a specific symbolic action. If it does, it would signal the offender's exclusion and, therefore, not be part of an atonement ritual.9 The first step in this process is to avoid an audience. Matthew 18:15-20 is thus best understood as a church (or community) rule consisting of five sentences in the style of casuistic law, which could either affect reconciliation or lead to the exclusion of the offenders from their community (Luz 2001:448).

Other possible examples of instructions for conducting atonement rituals occur in Matthew 6:1-18,10 which presents Jesus' teaching on the appropriate way to undertake the important religious duties of almsgiving (Matt. 6:2-4), prayer (Matt. 6:5-15), and fasting (Matt. 6:16-18). All three these religious duties were linked to the atonement of sin in Judaism in that, while fasting and prayer are often combined to express penitence (see the Day of Atonement in Lev. 16:29-31; 23:27-32), almsgiving, according to Tobit 12:8, "rescues from death and purges away all sin" (France 2007:232).

Almsgiving (Matt. 6:2-4) was an important religious duty, which, in the first century, was organised into a system of care for the poor located in the synagogues (France 2007:235). The verb  ("to sound a trumpet") could be a reference to trumpets that were blown on feast days (Joel 2:15; m. Ta,an. 2:5) when alms were asked for (see b. Ber. 6b; b. Sanh. 35a). It is thus possible that Jesus is critiquing an unknown ritual undertaken on feast days (Davies & Allison 1988:578). Matthew 6:2, however, locates the act of almsgiving in the synagogue or on the streets

("to sound a trumpet") could be a reference to trumpets that were blown on feast days (Joel 2:15; m. Ta,an. 2:5) when alms were asked for (see b. Ber. 6b; b. Sanh. 35a). It is thus possible that Jesus is critiquing an unknown ritual undertaken on feast days (Davies & Allison 1988:578). Matthew 6:2, however, locates the act of almsgiving in the synagogue or on the streets

11It is, therefore, best understood as a spiritual discipline to be performed when asked for, or as a rite incorporated into the rituals enacted during the gatherings in the synagogue. Matthew also does not make an explicit link between the act of almsgiving and receiving atonement.12 Even if almsgiving was part of a ritual, it furthermore does not automatically imply that it was performed for atonement.

11It is, therefore, best understood as a spiritual discipline to be performed when asked for, or as a rite incorporated into the rituals enacted during the gatherings in the synagogue. Matthew also does not make an explicit link between the act of almsgiving and receiving atonement.12 Even if almsgiving was part of a ritual, it furthermore does not automatically imply that it was performed for atonement.

Penitential prayer (Matt. 6:5-15) occurs in a number of passages of the Hebrew Bible as an option for asking for atonement by those who were unable to reconcile with God through the temple (Hägerland 2006:171).13The question is whether the Lord's Prayer (Matt. 6:9-14) conforms to first-century Jewish penitential prayers, which exhibit some traits of formalisation (for example, in the expressions used in their confessional part). Hägerland (2006:176) convincingly argues that it does not. In the Lord's Prayer, there are no reminders of God's salvation in the past, no references to the covenant or ancestors' merits, nor multiple synonyms used in expressing the remorse of the one praying that characterise penitential prayers (Hägerland 2006:174-176). Instead, the petition for forgiveness gives a different motivation for God's forgiveness of sin (the petitioner's act of forgiving) (Hägerland 2006:180). While the Lord's Prayer thus refers to the forgiveness of sin, it is not to be considered primarily as a penitential prayer.

Jesus' teaching on fasting (Matt. 6:16-18) assumes that his followers did fast.14 The question was how they should do so. According to Malina and Rohrbaugh (1992:64), "fasting is a ritualized, highly compressed piece of behaviour" that communicates the self-humiliation of the one fasting to God, in order to elicit his help or forgiveness.15 Because of its close link with repentance and mourning, fasting was often accompanied by other rites and symbols16 such as weeping, wearing a sackcloth, covering the head with ashes or soil, and rending clothing (Nolland 2005:294-295). These rites and symbols, as examples of stylised social behaviour, drew attention to the "hypocrites" who ironically made themselves unrecognisable in order to be recognised

in order to be recognised  (Davies & Allison 1988:618). Fasting can thus be understood as a ritual comprised of rites and symbols, which, in some instances,17 signalled remorse and the need for forgiveness. Matthew, however, does not emphasise this link with atonement.

(Davies & Allison 1988:618). Fasting can thus be understood as a ritual comprised of rites and symbols, which, in some instances,17 signalled remorse and the need for forgiveness. Matthew, however, does not emphasise this link with atonement.

While almsgiving and prayer can thus be understood as being rites, and fasting a ritual, which may be linked to atonement in Judaism, Matthew is critical of their ritual expression. Instead of undertaking them to receive human approval, they should, according to the Matthean Jesus, be undertaken in secret  - 6:4, 6) so that only God knows thereof. All stylised social behaviour intended to draw the attention of its audiences is to be avoided (for example, giving alms with fanfare, openly fasting, and praying in public). Nor should it be performed at special events (festivals) or in special places (in the synagogue or in a busy street) to draw the attention of others. Culturally determined practices (symbols) such as not caring for one's appearance should be avoided. Furthermore, the official cult is ignored and may thus be understood to be inessential (Betz 1985:68). This criticism of Matthew raises the question as to whether there is a general denouncement of ritual expressions of piety in his Gospel? In other words, does the Matthean Jesus' teaching signal the shift of religious expression away from the cult and the public sphere to the private practice thereof? While one cannot answer these questions conclusively, it is clear that, in these three instances, the Matthean Jesus envisions no role for either the temple or its functionaries.

- 6:4, 6) so that only God knows thereof. All stylised social behaviour intended to draw the attention of its audiences is to be avoided (for example, giving alms with fanfare, openly fasting, and praying in public). Nor should it be performed at special events (festivals) or in special places (in the synagogue or in a busy street) to draw the attention of others. Culturally determined practices (symbols) such as not caring for one's appearance should be avoided. Furthermore, the official cult is ignored and may thus be understood to be inessential (Betz 1985:68). This criticism of Matthew raises the question as to whether there is a general denouncement of ritual expressions of piety in his Gospel? In other words, does the Matthean Jesus' teaching signal the shift of religious expression away from the cult and the public sphere to the private practice thereof? While one cannot answer these questions conclusively, it is clear that, in these three instances, the Matthean Jesus envisions no role for either the temple or its functionaries.

3.2 Texts that report the execution of a ritual

There are instances in Matthew (5:23-24; 8:1-4) where Jesus refers to atonement rituals performed in the temple.18

In Matthew 5:23-24, Jesus addresses his audience directly and instructs them that, if they are about to give a sacrifice and they remember that a brother had something against them, they should leave their offering at the altar and first reconcile with their brother before returning to complete their offering to God. This short illustration emphasises that receiving forgiveness from God through the giving of an offering necessitates seeking forgiveness of those who have been wronged. It furthermore presupposes participation in the sacrificial system. It appears that the altar, to which Jesus refers, is the one for burnt offerings located in the courtyard of the Temple in Jerusalem (Betz 1995:222).

The ritual itself is described briefly by means of technical terminology, as comprising the acts of carrying  an offering

an offering  to

to  the altar in order to deposit it on top of it

the altar in order to deposit it on top of it  (Betz 1995:222). The specific space (the altar in the temple), actions (carrying and placing an offering) and symbol (the offering) of the ritual are thus clear. It is noteworthy that Jesus does not mention a priest functioning as an intermediary who receives the gift to place it on the altar. It is, however, not explicitly stated that the offering could thus explain why it is intended to atone for the sin of the person bringing it. It is simply described as a gift

(Betz 1995:222). The specific space (the altar in the temple), actions (carrying and placing an offering) and symbol (the offering) of the ritual are thus clear. It is noteworthy that Jesus does not mention a priest functioning as an intermediary who receives the gift to place it on the altar. It is, however, not explicitly stated that the offering could thus explain why it is intended to atone for the sin of the person bringing it. It is simply described as a gift

- "gift", "present"). The nature of the offering did not require a priest as an intermediary. The intended parallelism between bringing an offer before God and seeking to reconcile with a brother, however, suggests that the offering is an attempt to atone for sins committed against God. What is important is that, if the matter with the offended brother is not resolved,19 the effectiveness of the ritual is destroyed (Betz 1995:222). The demand for reconciling with others before offering a sacrifice does not negate temple worship; instead, it emphasises that the formal observance of a ritual without genuine remorse evident in reciprocal behaviour is meaningless (Davies & Allison 1988:518). This emphasis on the appropriate inner conviction when conducting a ritual echoes Hosea 6:6, which states that God demands mercy rather than offerings (see Matt. 9:13).

- "gift", "present"). The nature of the offering did not require a priest as an intermediary. The intended parallelism between bringing an offer before God and seeking to reconcile with a brother, however, suggests that the offering is an attempt to atone for sins committed against God. What is important is that, if the matter with the offended brother is not resolved,19 the effectiveness of the ritual is destroyed (Betz 1995:222). The demand for reconciling with others before offering a sacrifice does not negate temple worship; instead, it emphasises that the formal observance of a ritual without genuine remorse evident in reciprocal behaviour is meaningless (Davies & Allison 1988:518). This emphasis on the appropriate inner conviction when conducting a ritual echoes Hosea 6:6, which states that God demands mercy rather than offerings (see Matt. 9:13).

A second report of an atonement ritual is found in Matthew 8:1-4,20 where Jesus commands a  21whom he had healed, to give a purification offer in the temple22 before showing himself to the priests. Jesus' command envisions not only a place for rituals that would enable the healed leper to be reintegrated into his community (Malina & Rohrbaugh 1992:70-74), but also a role for a priest to act as an intermediary.23

21whom he had healed, to give a purification offer in the temple22 before showing himself to the priests. Jesus' command envisions not only a place for rituals that would enable the healed leper to be reintegrated into his community (Malina & Rohrbaugh 1992:70-74), but also a role for a priest to act as an intermediary.23

The healing of the leper, as described by Matthew, consists of an ordered sequence of stylised social behaviour, of which the core is Jesus' deliberate double action of stretching  out his hand and touching

out his hand and touching  the leper before commanding him to be cleansed

the leper before commanding him to be cleansed  These actions would certainly have caught the attention of the onlookers (the audience), since they were to avoid all contact with lepers, according to Leviticus 5:3. To touch a leper had ritual consequences, because it resulted in their defilement (France 2007:307). In this instance, Jesus' action symbolises the healing and recovery of the leper. It can be argued that Jesus' healings were performed as rituals, since touching the afflicted was a common element in Jesus' healings (see Matt. 8:15; 9:20, 29; 20:34).24

These actions would certainly have caught the attention of the onlookers (the audience), since they were to avoid all contact with lepers, according to Leviticus 5:3. To touch a leper had ritual consequences, because it resulted in their defilement (France 2007:307). In this instance, Jesus' action symbolises the healing and recovery of the leper. It can be argued that Jesus' healings were performed as rituals, since touching the afflicted was a common element in Jesus' healings (see Matt. 8:15; 9:20, 29; 20:34).24

The passage also refers to a second ritual, which Jesus does not perform. Instead, Jesus commands the leper, per the prescripts of Moses, to show himself to a priest, in order to get official sanction allowing him to return to his family. This elaborate ritual cleansing could last for eight days (Lev. 14:8-10), or even longer if it necessitated a journey to Jerusalem to give an offering in the temple. According to Jesus, this was necessary, in order to witness  to the priest that he had been cured. The function of this ritual itself is not to atone for sin, but to cleanse the afflicted person from impurity. It is thus not, strictly speaking, an atonement ritual.

to the priest that he had been cured. The function of this ritual itself is not to atone for sin, but to cleanse the afflicted person from impurity. It is thus not, strictly speaking, an atonement ritual.

These two episodes, which both mention that a ritual has been enacted, presuppose both the acceptance and the functioning of the Law of Moses, the Temple, priest, and offerings. The Matthean Jesus' attitude towards the temple is thus clearly ambivalent in view of his silence on its role in Matthew 6:1-18. This ambivalence is also reflected in the remainder of Matthew's Gospel. On the one hand, some of the Matthean Jesus' pronouncements such as Matthew 23:18-19, which discusses the proper way of giving an offering, presuppose a place for the temple. On the other hand, other pronouncements by Jesus (Matt. 12:6; 26:61; 27:40), along with his symbolic action in the temple (Matt. 21:12-17), suggest that Matthew considered the temple to be irrelevant for his own community from both a historical25 and a theological viewpoint.

3.3 Texts that deal with the meaning, function, or implementation of a ritual

These texts differ from the ones discussed in the above two sections, in that they discuss the meaning and implementation of a ritual instead of merely reporting or commanding it. Of the four texts in Matthew that describe the implementation of an atonement ritual, two are performed by Jesus and two by Pilate.

The first example of an atonement ritual performed by the Matthean Jesus, which leads to a debate on its meaning, is when Jesus heals and forgives a paralytic in Matthew 9:1-8. Matthew reports the incident as being enacted in a stylised26 and ordered manner. The paralytic is brought  to Jesus (Matt. 9:2) who initially addresses him with an endearment formula

to Jesus (Matt. 9:2) who initially addresses him with an endearment formula  before instructing him to stand up

before instructing him to stand up  , pick up his bed

, pick up his bed  and go

and go  to his home.

to his home.

Jesus' action (his first pronouncement to the paralytic -

immediately caught the attention of the onlookers as it alludes to the words uttered by the High Priest in the temple27 and thus claims what only God may do - forgive a person's sins. The way in which Jesus claims God's authority, mediated by the temple (Matt. 9:6), causes the scribes to respond with anger (see the accusation of blasphemy in Matt. 9:3),28 fear and praise (Matt. 9:8).

immediately caught the attention of the onlookers as it alludes to the words uttered by the High Priest in the temple27 and thus claims what only God may do - forgive a person's sins. The way in which Jesus claims God's authority, mediated by the temple (Matt. 9:6), causes the scribes to respond with anger (see the accusation of blasphemy in Matt. 9:3),28 fear and praise (Matt. 9:8).

Jesus' words are a performative utterance (France 2007:345) that communicates that he had the authority to forgive sins. This authority is subsequently substantiated by the healing of the paralytic. The healing itself is an appropriate, culturally specific symbol for forgiveness, due to the link made between sin and illness in the first-century Mediterranean world (Malina & Rohrbaugh 1992:71; Nolland 2005:380). The healing, according to Matthew, specifically points to the Son of Man's all-embracing authority (Luz 2001:27). By healing the paralytic and forgiving his sins, Jesus effectively appropriated the role of the temple and its functionaries in affecting forgiveness. The healing of the paralytic can thus be viewed as an improvised29 atonement ritual.

The hand washing by Pilate (Matt. 27:24-26) is an example of a prophylactic30 atonement ritual. Prior to handing Jesus over to his executioners and when he realised that it was futile to reason with the assembled crowd ("He was gaining nothing",  , which was growing increasingly volatile

, which was growing increasingly volatile  can be translated "a riot was beginning" [so nrsv]), Pilate performed a ritual which not only signalled his innocence in the death of Jesus, but also Jesus' innocence of the charges brought against him.

can be translated "a riot was beginning" [so nrsv]), Pilate performed a ritual which not only signalled his innocence in the death of Jesus, but also Jesus' innocence of the charges brought against him.

Pilate is described as using an ordered sequence of stylised actions with which to focus the attention of his audiences in that he takes  water and washes

water and washes  31his hands in front of the crowd

31his hands in front of the crowd  and proclaims

and proclaims  "I am innocent of the blood of this one"

"I am innocent of the blood of this one"

. In terms of special place and occasion, he performs his ritual in front of Herod's palace32 during the trial of Jesus and in front of the assembled crowd, while he sits on an elevated tribunal

. In terms of special place and occasion, he performs his ritual in front of Herod's palace32 during the trial of Jesus and in front of the assembled crowd, while he sits on an elevated tribunal  from which Roman judges dispense justice (Matt. 27:19) (Luz 2005:498).

from which Roman judges dispense justice (Matt. 27:19) (Luz 2005:498).

Pilate communicates his innocence (special message) by washing his hands in water (a culturally appropriate symbol of innocence). The symbol of washing one's hands is polysemous, as it may have a Jewish and Hellenistic background.33 The Gentile ritual of expiation is different from Pilate's, in that it involves the ritual purification of a guilty, not an innocent person, which he claims to be (Luz 2005:498). Pilate's ritual can also function as a parody of the ritual for the exoneration from bloodguilt described in Deuteronomy 21:1-9 (Nolland 2005:1177). The bloodguilt ritual is performed when a murdered body is found and the murderer cannot be identified. Under these circumstances, the elders of the nearest town wash their hands  - Deut. 21:6 LXX) over a heifer whose neck has been broken in a stream with flowing water before they absolve their town from the bloodguilt with a solemn declaration (Deut. 21:8). This ritual purges them and their town of the bloodguilt of the murdered victim.

- Deut. 21:6 LXX) over a heifer whose neck has been broken in a stream with flowing water before they absolve their town from the bloodguilt with a solemn declaration (Deut. 21:8). This ritual purges them and their town of the bloodguilt of the murdered victim.

Pilate's solemn declaration is, however, not made to God as in Deuteronomy 21:8. Instead, it consists of the simple declaration that he is "innocent of the blood" of Jesus.34 Furthermore, the execution of Jesus has not yet happened and can thus still be prevented. Despite these discrepancies with the ritual in Deuteronomy 21:8, the eager response of the crowd reported by Matthew suggests that his audience has accepted Pilate's ritual proclamation that they are responsible for Jesus' death (Matt. 27:25).35 Pilate thus succeeds, according to his audience in Matthew, in shifting the blame for Jesus' death to the crowd. The clause "see to it yourself"  , probably a Latinism, links Pilate and Judas, in that the singular equivalent

, probably a Latinism, links Pilate and Judas, in that the singular equivalent  occurs in Matthew 27:4 in response to Judas' attempt to undo his betrayal of Jesus.

occurs in Matthew 27:4 in response to Judas' attempt to undo his betrayal of Jesus.

While Pilate attempted to deny his responsibility, Judas freely acknowledged his. Judas' attempt at atonement (Matt. 27:3-10) is to return the money he received for betraying Jesus. His confession that he "has sinned"  by betraying "innocent blood"

by betraying "innocent blood"  is a common expression in the Old Testament (Hagner 1995:811). Like Pilate, Judas thus improvises36 an atonement ritual by appropriating Old Testament atonement language.

is a common expression in the Old Testament (Hagner 1995:811). Like Pilate, Judas thus improvises36 an atonement ritual by appropriating Old Testament atonement language.

Matthew 26:26-27 describes the second ritual performed by Jesus during his sharing of the Passover meal with his disciples (Matt. 26:17-30). This ritual is an ordered sequence of stylised social behaviour which has been altered to focus the attention of its audience. Jesus takes  , breaks

, breaks  , blesses

, blesses  and gives (

and gives ( the bread before instructing the disciples to take

the bread before instructing the disciples to take  and eat it

and eat it  . He similarly takes

. He similarly takes  a cup, gives thanks

a cup, gives thanks  for it and gives it

for it and gives it  to them with the command to drink

to them with the command to drink  from it. It is, furthermore, performed as a special event at a special time for a special occasion (the week of Passover) with a special message expressed with the help of the symbols of bread

from it. It is, furthermore, performed as a special event at a special time for a special occasion (the week of Passover) with a special message expressed with the help of the symbols of bread  and a cup

and a cup  .37Jesus also describes his blood as "the blood of the covenant which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins"

.37Jesus also describes his blood as "the blood of the covenant which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins"

Jesus' words establish a deliberate link between the ritual performed by him and the ritual performed by Moses in Exodus 24:8.38 During the covenant ceremony at Sinai, in Exodus 24:8, Moses took the blood from the offerings of the twelve tribes and, while throwing half thereof on the altar and the other half on the people, he proclaimed: "Behold the blood of the covenant which the Lord has made with you in accordance with all these words" (NRSV).

Jesus' words establish a deliberate link between the ritual performed by him and the ritual performed by Moses in Exodus 24:8.38 During the covenant ceremony at Sinai, in Exodus 24:8, Moses took the blood from the offerings of the twelve tribes and, while throwing half thereof on the altar and the other half on the people, he proclaimed: "Behold the blood of the covenant which the Lord has made with you in accordance with all these words" (NRSV).

To Matthew, it appears that Jesus did not only recall the ritual of Moses, but that he used it to convey that he is the fulfilment of this covenant. This reinterpretation process already started in the Old Testament in that Exodus 24:8, which states that the redemption from captivity (exile) is a "repayment" and that it will happen "by the blood of the covenant", is cited in Zechariah 9:9-12. According to Eubank (2013:174), the implication of Zechariah's words is that God's repayment of Israel's debt and her restoration as a nation is due to the covenant that was cut at Sinai. Matthew 21:5 also cites these words from Zechariah 9:9, when Jesus enters Jerusalem,39 mentioning the ransom God has paid for his people (Eubank 2013:171-173). To Matthew, the themes of covenant, exile, blood, sin and the death of Jesus are thus all linked. The way in which Matthew edits Mark's account of the Last Supper (Mark 14:17-27) by adding a conjunction  at the beginning of Mark 14:24, and an interpretive phrase

at the beginning of Mark 14:24, and an interpretive phrase  at the end in Matthew 26:28, links the new covenant, which the Old Testament prophets had related to the forgiveness of sin (see Ezek. 16:63; Jr 31:34), with Jesus' forthcoming death. His forthcoming crucifixion was thus a sacrifice that would inaugurate God's new covenant.

at the end in Matthew 26:28, links the new covenant, which the Old Testament prophets had related to the forgiveness of sin (see Ezek. 16:63; Jr 31:34), with Jesus' forthcoming death. His forthcoming crucifixion was thus a sacrifice that would inaugurate God's new covenant.

To Matthew, Jesus had fully atoned for the sins of his people, thereby making the temple, and the sin offerings associated with it, obsolete. In Matthew's narrative, Jesus' Last Supper is not a true atonement ritual in that it refers to Jesus' forthcoming death affecting forgiveness, instead of itself already enacting atonement.

3.4 Texts that stem directly from ritual use (confessional and liturgical formula)

The question is raised as to whether Matthew's formulations of the Lord's Prayer and the Last Supper originated in contexts where they were used as part of a ritual. While this is likely in the case of the Lord's Supper, it is not as apparent regarding the Lord's Prayer. Since Matthew does not discuss the Lord's Supper from the perspective of his community's celebration thereof, it was discussed in the preceding section as an example of a text that concerns itself with the meaning, function, or implementation of a ritual.

3.5 Texts that are connected synecdochically with a ritual

A text may (according to Strecker) echo, allude, or refer to a rite, even though the text may not be about ritual per se (DeMaris 2008:6). An example of a synechdochical echo of a ritual occurs in Matthew 20:28, where the Matthean Jesus describes his life as a  whereby Israel's debts were to be remitted (Eubank 2013:150-151). The term

whereby Israel's debts were to be remitted (Eubank 2013:150-151). The term  (price of release, ransom) refers to a payment or exchange. In Leviticus 19:20-22, it refers to the ritual of sacrificing an animal to atone for a transgression. The ritual signalled that the life of an innocent animal had been exchanged (ransomed) by a man who was guilty of intercourse with a bondmaid and that, thanks to his sacrifice to God, the sacrificial animal had borne the punishment that should have been his.

(price of release, ransom) refers to a payment or exchange. In Leviticus 19:20-22, it refers to the ritual of sacrificing an animal to atone for a transgression. The ritual signalled that the life of an innocent animal had been exchanged (ransomed) by a man who was guilty of intercourse with a bondmaid and that, thanks to his sacrifice to God, the sacrificial animal had borne the punishment that should have been his.

The term  not only refers to individual salvation. At times, it refers to the collective salvation of Israel (Eubank 2013:152-153). In Exodus 6:6, for example, God commands Moses to tell the Israelites, "I will ransom

not only refers to individual salvation. At times, it refers to the collective salvation of Israel (Eubank 2013:152-153). In Exodus 6:6, for example, God commands Moses to tell the Israelites, "I will ransom  LXX) you with uplifted arm", while in Micah 6:4 ("For I brought you from the land of Egypt and ransomed

LXX) you with uplifted arm", while in Micah 6:4 ("For I brought you from the land of Egypt and ransomed  LXX) you from the house of slavery"), God recalls the Exodus ending, due to a ransom being paid.40

LXX) you from the house of slavery"), God recalls the Exodus ending, due to a ransom being paid.40

Jesus' reference to giving his life as a  thus echoes the Old Testament ritual of giving a sacrifice to atone for the sins of an individual, and in a metaphorical sense, for the whole of Israel.

thus echoes the Old Testament ritual of giving a sacrifice to atone for the sins of an individual, and in a metaphorical sense, for the whole of Israel.

4. CONCLUSION

According to DeMaris (2008:4-6), Strecker's rite (or ritual)-in-text taxonomy

reminds us that the interface between text and rite is varied and complex: a given text may describe, prescribe, or interpret a rite; the verbal elements of rite may appear directly in a text or a text may do no more than hint at or echo a rite.

When used to read the various texts in Matthew relating to atonement rites and rituals, the following becomes apparent:

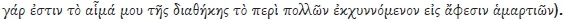

4.1 Atonement rituals

Compared to the other Synoptic Gospels, Matthew has a significant number of references to atonement rituals that are unique to him. This is to be expected considering Matthew's engagement with Formative Judaism and the importance of atonement for the latter. These atonement rituals function in a complex manner regarding existing rituals, as some serve to reinforce them, while others reinterpret, and even nullify them. For example, in Matthew 6:1-18, which gives instructions on how to practise three prominent religious rites that are linked to the atonement of sin in Judaism, Jesus changes these from public to private practices, with no place for the temple, synagogue, or priests in their enactment. Other actions have their public role as rituals affecting atonement affirmed. Matthew 5:23-24 and 8:1-4, for example, report a ritual being performed that presupposes the validity of the Law of Moses, the temple, offerings, and priests. Other enactments of atonement by the Matthean Jesus replace Jewish rituals such as Jesus' healing of the paralytic (Matt. 9:1-8), or reinterpret them as in Jesus' celebration of the Passover meal41 (Matt. 26:17-30). To Matthew, Jesus had the authority to reinterpret and change Old Testament rituals as he saw fit.

It appears that atonement rituals in Matthew occur at the critical juncture between Matthew's community and that of Judaism in that primarily Jewish42 atonement rituals are being appropriated or negated. The potential for conflict, when appropriating and negating the rituals of others, should not be underestimated (see the cleansing of the temple by Jesus - Matt. 21:12-13), since their ritual character allows others to recognise their reinterpretation and appropriation, challenging them to respond to it in a positive or negative manner. While it is likely that the literate elite would have understood the radical nature of the Matthean Jesus' teaching on the Law, challenges to rituals or places associated therewith would not have escaped the notice of the non-elite (see the conflict arising from Jesus' actions in the temple).

Differences over how forgiveness and reconciliation with God and others should occur can result in fierce conflict. A tragic example of this is the history of interpretation of the ritual enactments during Jesus' trial, wherein Matthew controversially describes the participation and culpability of the crowd present at that trial. Matthew 27:24-26 depicts the events following Pilate's atonement ritual for himself as an anti-atonement ritual, in which the blood of Jesus is interpreted in terms of the guilt it conveys to the Jews, and not the salvation it would bring, as promised by Jesus during his reinterpretation of the Passover meal (Matt. 26:26).

4.2 The majority of, but not all Matthean atonement rituals are linked to Jesus' power and authority43

Even when he is not surpassing the temple and the priest, resulting in the shocked comments of onlookers (Matt. 9:1-8), Jesus commands others to remain faithful (Matt. 5:23-24; 8:1-3) or intentionally ignore them (Matt. 6:1-18). The Matthean Jesus undeniably has the authority to initiate new rituals/processes (Matt. 18:15-20) or to reinterpret old ones (Matt. 26:17-30) that claim the ultimate authority to forgive sin, for himself (and his followers - Matt. 9:8). To Matthew, Jesus took the place of the temple and all sacrificial offerings, and in so doing inaugurated a new covenant between God and his people.

4.3 Prophylactic rituals

In terms of the timeline of his narrative, Matthew refers to two prophylactic rituals that claim to atone for a future sin (Pilate's washing of his hands), or point to a future atoning deed (Jesus' Passover meal that signifies his forthcoming death).

4.4 Improvising atonement rituals

Not only Jesus, but also Judas and Pilate improvise atonement rituals in Matthew (the last two being unique to Matthew). This supports Klingbeil's (2007:16) observation that rituals can be birthed at any time within personal or societal contexts. These rituals are often polysemous in that they can simultaneously allude to and appropriate different existing rituals (Pilate's handwashing and Jesus' sharing of bread and a cup). It is, therefore, to be expected that their affect will at times be ambiguous. (Is it easier to heal than to forgive and was the crowd in Jerusalem saved by their blood offering of Jesus?)

It is clear from the above that Platvoet's operational definition is a helpful heuristic tool. More sophisticated analytical tools and theories will, however, be needed to fully explore Matthew's atonement rituals and the way in which they emphasise Jesus' authority.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Betz, H.D. 1985. A Jewish-Christian cultic didache in Matt. 6:1-18: Reflections and questions on the problem of the historical Jesus. In: H.D. Betz (ed.), Essays on the Sermon on the mount (Philadelphia: Fortress Press), pp. 55-69. [ Links ]

Betz, H.D. 1995. The Sermon on the mount: A commentary on the Sermon on the mount, including the Sermon on the plain (Matthew 5:3-7:27 and Luke 6:20-49). Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Davies, W.D & Allison, D.C. 1988. A critical and exegetical commentary on the Gospel according to Saint Matthew 1-7. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Davies, W.D & Allison, D.C. 1997. A critical and exegetical commentary on the gospel according to Saint Matthew 19-28. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

DeMaris, P.E. 2008. The New Testament in its ritual world. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Eubank, N. 2013. Wages of cross-bearing and debt of sin: The economy of heaven in Matthew's Gospel. Berlin: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

France, R.T. 2007. The Gospel of Matthew. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Geertz, C. [1973] 2009. The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. 65th ed. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Grimes, R.L. 1995. Beginnings in ritual studies. 2nd ed. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Gundry, R.H. 1982. Matthew: A commentary on his literary and theological art. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Hägerland, T. 2006. Jesus and the rites of repentance. New Testament Studies 52:166-187. [ Links ]

Hägerland, T. 2012. Jesus and the forgiveness of sins: An aspect of his prophetic mission. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Hagner, D.A. 1993. Matthew 1-13. Dallas, TX: Word Books. [ Links ]

Hagner, D.A. 1995. Matthew 14-28. Dallas, TX: Word Books. [ Links ]

Klingbeil, G.A. 2007. Bridging the gap: Ritual and ritual texts in the Bible. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Luz, U. 2001. Matthew 8-20: A commentary. Minneapolis, MN,: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Luz, U. 2005. Matthew 21-28: A commentary. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Malina, B.J. & Rohrbaugh, R.L. 1992. Social science commentary on the Synoptic Gospels. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Nolland, J. 2005. The Gospel of Matthew: A commentary on the Greek text. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Platvoet, J.G. 1995. Pluralism and identity: Studies in ritual behaviour. In: K.V.D. Toorn & J.G. Platvoet (eds), Pluralism and identity: Studies in ritual behaviour (Leiden: Brill), pp. 25-51. [ Links ]

Strecker, O. 1999. Die liminale Theologie des Paulus: Zugänge zur paulinischen Theologie aus kulturanthropologischer Perspektive. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [ Links ]

1 Jesus' explicit teaching on forgiveness occurs in passages containing either the noun ἅϕεσις(Matt. 26:28) or its cognate verb ἁϕẗημι (Matt. 6:12, 14, 15; 9:2, 5, 6; 12:31, 32; 18:21, 27, 35).

2 In view of the emphasis on the need for repentance in order to receive forgiveness in Second Temple Judaism (Hägerland 2006:171), it is an important question whether Jesus' atonement ministry in Matthew also required moral (for example, forgiving others their sins - Matt. 6:12, 14-15) and ritual actions (Matt. 5:23-24) which signalled repentance. For a discussion on whether the historical Jesus expected ritual behaviour along with moral actions when repenting, see Hägerland (2006:166-187).

3 Various narrated actions of Jesus such as his healing of the sick (Matt. 9:6) and meals with sinners and other undesirables (Matt. 9:9-13) enacted and exemplify forgiveness, but are not rituals. In addition, the process prescribed in Matthew 18:15-20 is not a ritual.

4 Rituals, however, do distinguish between insiders and outsiders in the sense that they are often not entirely understood by those who do not belong to the particular group practising a specific ritual (Klingbeil 2007:15).

5 Cult, from the Latin cultus (a participle of the verb colere, "cultivate, care for, honour, revere") describes the entirety of religious actions of a specific group (Klingbeil 2007:10-11).

6 In this article, it will be indicated where these terms are used instead of those originally used by an author to ensure the consistent use of terminology.

7 In view of Klingbeil's distinction between rites and rituals, Strecker's reference to rituals will be changed to rites in the relevant sections, since his definition of rite is closer to Klingbeil's definition of a ritual.

8 There is no indication that "binding and loosening" (Matt. 18:18) involved any symbolic actions.

9 An example would be the instruction in Luke 10:11, which does not occur in Matthew, to wipe the dust off the streets of the towns that had not accepted the disciples of Jesus and their message.

10 Betz (1985:57) describes this section, from a form-critical point of view, as a pre-Matthean cultic didache.

11 The way in which alms were collected on the Sabbath in the synagogue (see Justin, 1 Apol. 67; b. Sabb. 150a) and the giving thereof on the streets to those who beg was calculated to focus the attention of others (an audience) on it. Due to the brevity of Jesus' remark, it is, however, impossible to decisively conclude that it refers to a ritual (that it was performed in a stylised way on a specified day).

12 Mark 12:41-44 contains an episode with more detail. It provides a setting (the temple) and describes behaviour that is meant to draw the attention of the audience. There is, however, no parallel of this episode in Matthew.

13 See 1 Kings 8:46-50; Lamentations 3:40-42; Daniel 9:13; Hosea 14:2-3 and Jonah 3:8.

14 Matthew 9:14-15 suggests that Jesus' disciples did not fast, but would do so in the future (France 2007:254).

15 Ben Sira, for example, supports the practice of repenting by fasting (Ecclesiastes 34:26) as does the Psalms of Solomon 3:6-8.

16 See 2 Samuel 1:11-12; Nehemiah 9:1; Psalms 35:13-14; Daniel 9:3; Judith 8:5; 1 Maccabees 3:47 and Canticles 20.89.

17 It is a polysemous ritual in that it can convey different meanings (for example, loss or remorse).

18 Matthew refers to meals in which Jesus ate with sinners and tax collectors. In the case of Matthew, the tax collector signified his acceptance into Jesus' in-group (Matt. 9:9-13). While meals are ritualistic in nature, Matthew does not describe how this specific meal was conducted.

19  "become reconciled", occurs only here in the New Testament (Betz 1995:222).

"become reconciled", occurs only here in the New Testament (Betz 1995:222).

20 Matthew 8:1-4 is the first of three miracle stories in 8:1-17 which relate to Jesus' healing and recuperation of the sick which is, in turn, part of a major section of the Gospel (chapters 8-9) that focuses on Jesus' miraculous deeds.

21 The  in Matthew suffer from a disfiguring skin condition (not necessarily Hansen's disease), which rendered them unclean (Lev. 13-14). Their uncleanliness was considered to be permanent, with the result that they were excluded from normal society (Lev. 13:45-46). If the skin condition did disappear for some reason, the afflicted persons had to be examined by a priest and an appropriate offering and cleansing ritual undertaken (Lev. 14:1-32). Only then would they be allowed back into their society. The recuperation of a leper was not a simple process. In the Old Testament, the cure of a leper was even viewed as being on par with raising the dead (2 Kgs 5:7). With no other disease is the afflicted person described in the New Testament as being "cleansed" instead of being "cured."

in Matthew suffer from a disfiguring skin condition (not necessarily Hansen's disease), which rendered them unclean (Lev. 13-14). Their uncleanliness was considered to be permanent, with the result that they were excluded from normal society (Lev. 13:45-46). If the skin condition did disappear for some reason, the afflicted persons had to be examined by a priest and an appropriate offering and cleansing ritual undertaken (Lev. 14:1-32). Only then would they be allowed back into their society. The recuperation of a leper was not a simple process. In the Old Testament, the cure of a leper was even viewed as being on par with raising the dead (2 Kgs 5:7). With no other disease is the afflicted person described in the New Testament as being "cleansed" instead of being "cured."

22 There are, however, instances in Matthew (see 9:1-8) where Jesus did not explicitly command those he had healed to give an offering in the temple.

23 Matthew 5:25-26 gives an example of reconciliation through compensation. The manner in which this was to be enacted is not described. Therefore, it cannot be ascertained whether this is an atonement rite or ritual.

24 The healing is not, in the first instance, possible because it is the will of God, but because it is the will of Jesus, as is made clear by his words that he is willing to heal the leper  . His will is, according to Matthew, to be understood as being on par with that of God (Nolland 2005:349). Jesus' unique authority is thus emphatically emphasised (Hagner 1993:200). The leper, who had prostrated

. His will is, according to Matthew, to be understood as being on par with that of God (Nolland 2005:349). Jesus' unique authority is thus emphatically emphasised (Hagner 1993:200). The leper, who had prostrated  himself before Jesus while addressing him as "Lord"

himself before Jesus while addressing him as "Lord"  is thus validated in his estimation of Jesus' authority.

is thus validated in his estimation of Jesus' authority.

25 Historically, Matthew was probably writing nearly two decades following the temple's destruction so that it was no longer of any relevance for the post-war Matthean community. References to the temple thus signal Matthew's failure to contemporise these sayings.

26 France (2007:347) calls the references in the text "stage directions".

27 The claim that priests would pronounce sins to be forgiven when atoning for the sins of others through a sin- or guilt-offering (see Lev. 4:20-26) has been challenged, since there is no reference to priestly pronouncements of forgiveness in early Jewish literature (Hägerland 2012:134-135). It is also debatable whether the high priest had the authority to forgive sins.

28 Jesus not only pronounced that God had forgiven the paralytic his sins (as a priest in the temple would), or that God would do so in the future, but rather that he himself had already forgiven them (Matt. 9:2). Since first-century Judaism believed that God had reserved for himself the declaration of forgiveness in an ultimate sense on the Day of Judgement, the scribes understood Jesus as claiming to do what only God could, hence their accusation that he was blasphemous (Nolland 2005:381).

29 It is improvised, since the healing is narrated as a rebuttal of the scribes' response to Jesus' forgiveness of the paralytic's sins and not as a premeditated fixed step in the forgiveness of sins.

30 It is conducted before the sin (the execution of an innocent man) is committed (Nolland 2005:1176-1177).

31 Matthew does not use the word commonly used for "wash"  in the remainder of the New Testament and the LXX. Instead, he uses a New Testament hapax legommenon

in the remainder of the New Testament and the LXX. Instead, he uses a New Testament hapax legommenon  which occurs only three times in the LXX, in each case with negative overtones (Nolland 2005:1176).

which occurs only three times in the LXX, in each case with negative overtones (Nolland 2005:1176).

32 Nolland (2005:1170-1171) supports the location of Pilate's praetorium being Herod's palace instead of the Fortress Antonia, although this cannot be conclusively proven. The bema was apparently a temporary one set up when the governor was in residence.

33 For Old Testament background, see Psalms 26:6; 73:13, and especially Deuteronomy 21:6-8; for Hellenistic background, see Herodotus 1.35; Virgil, Aeneid 2.719: Sophocles, Ajax 654 (Hagner 1995:826). In the Graeco-Roman texts, the intention of washing one's hands is to become clean again; it is not a symbolic expression of being guilt free and, therefore, not in need of cleaning (Nolland 2005:1176-1177). In Psalms 26 (LXX 25) and 73 (LXX 72), it seems to signal both moral innocence and ritual purity (see Ps. 24:4).

34 In this instance, blood functions as a symbol for the life of Jesus.

35 It is doubtful whether the words of the crowd can be interpreted as a double entendre, meaning that, while they are responsible for Jesus' death, they are simultaneously saved by it.

36 The public return of the reward he had received for betraying Jesus is described as an expression of profound remorse and not as a fixed step of a defined ritual.

37 The cup is a metonymy for the wine it contains.

38 This link between Jesus' words about the blood of the covenant to the forgiveness of sins is unique to Matthew (Eubank 2013:175). Matthew 3:1-12 does not depict John's baptism as an atonement ritual, since he underplays the role of John the Baptist's rite in mediating God's forgiveness by omitting the reference in Mark 1:4b  to him conferring the forgiveness of sin through his baptism of sinners in his version (Matt. 3:2). Instead, he uses it as a description of Jesus' death

to him conferring the forgiveness of sin through his baptism of sinners in his version (Matt. 3:2). Instead, he uses it as a description of Jesus' death

(Gundry 1982:528; Davies & Allison 1997:474).

(Gundry 1982:528; Davies & Allison 1997:474).

39 Eubank (2013:173) translates  in Zechariah 9:12 as "repay", instead of "restore" (see NRSV), because it fits the context of both Zechariah 9 and the quoted Exodus 21:34 better, and it is in line with the Septuagintal interpretation thereof (

in Zechariah 9:12 as "repay", instead of "restore" (see NRSV), because it fits the context of both Zechariah 9 and the quoted Exodus 21:34 better, and it is in line with the Septuagintal interpretation thereof ( is translated as

is translated as  in the LXX).

in the LXX).

40 Prophecies of the end of future exiles also use ransom language (see Isa. 43:1; Jr. 31:11 [38:11 LXX]; Micah 4:10).

41 Passover as a ritual is both a reminder of God's salvation in the past and of his promised future salvation of his people. It is not a true atonement ritual, in that it refers to, but does not enact the full restoration of God's relationship with his people. Unlike Mark, Matthew avoids any mention of the sacrifice of the Passover lamb (see Matt. 26:17), while Passover is linked to the crucifixion of the Son of Man (Matt. 26:2), and elaborated on by the reference to the proximity of the  (Matt. 26:18).

(Matt. 26:18).

42 Some of the atonement rituals of Jesus and other mediators of atonement are, however, polysemous, in that they can refer to more than one intertextual context (for example, Matt. 27:24-26 can refer to a Jewish or Hellenistic context).

43 In Matthew, authority is often linked to Jesus' teaching and ritual deeds (Matt. 7:29; 8:9; 9:6, 8; 10:1; 21:23, 24, 27; 28:18). The atonement rituals of Pilate and Judas are not linked to the authority of Jesus.