Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.37 n.1 Bloemfontein 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v37i1.6

ARTICLE HEADING

African postfoundational practical theology1

Prof J.C. Müller

Research Fellow of the University of the Free State, South Africa. E‑mail: julian.muller@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Practical theology is located in a fragile, vulnerable space between various disciplines, where it is exposed to multiple different narratives. The author proposes a postfoundational, narrative approach to practical theology that favours the local over the global and the specific over generalisations. Africa is taken as the defining context for the understanding and development of a specific postfoundational practical theology. People and their stories are central, and this requires a co- construction of meaning with "co-researchers". The author's "seven movements", as published in other articles, is used with an Ubuntu research project as a case study. The "seven movements" facilitate the telling and retelling of unheard stories, particularly stories of the marginalised and vulnerable. This way of doing practical theology takes the experiences of "co-researchers" seriously and conducts research wíth people rather than on them. The researcher's focus is concrete, local, and contextual, but also extends beyond the local by engaging in transdisciplinary conversation and developing interpretations that point beyond the local.

Keywords: Postfoundational, Practical theology, African, Narrative, Ubuntu research

Trefwoorde: Postfundamentele, Praktiese teologie, Afrika, Narratief, Ubuntu navorsing

1. STORY AND IMAGINATION

Practical theology is essentially an in-between discipline. It dwells in the gaps between the various theological disciplines, while it is also multilingual in the sense that it simultaneously speaks the languages of the humanities, the social sciences, and Theology (Browning 1991; Heitink 1993). Bochner and Ellis (1996:18) have pointed out that "[t]he walls between social sciences and humanities have crumbled", and the same can be said about the walls between Theology and other disciplines.

In this in-between land, the practical theologian is confronted with, and exposed to multiple realities or to a variety of narratives. Working in this context of multidisiplinary research draws me increasingly into the epistemology and methodology of narrative inquiry. Narrative inquiry assumes, fosters and facilitates the entering of the in-between landscape, the borderland. A suitable metaphor would be the ecotone (cf. Müller 2011), which is the territory of mutations and hybrids - a place where organisms of opposite territories interact and new species develop. In the in-between land, where practical theology operates, an "ecotone" develops and becomes a space for the development of stories of alternative realities. With this in mind, we can say that, in this practical theological ecotone, the emphasis shifts from "what" questions to "who" questions. Stories are always about people and people are our primary concern - living people in real contexts.

Where there are people, there are stories, and where there are stories, more stories develop. The fruitful space of the ecotone is like a breeding space for the development of new "species". Where that happens, there are new stories to be imagined and to be told. Imagination is often regarded as something abstract and distant from the real world. However, imagination is not theoretical, but embodied, local, and contextual. Our imaginings draw on our perceptual and embodied knowing, as well as on our rememberings, our stories of past encounters and experiences. "It is the invisible but felt presence of the other that ignites imagination leading to connection" (Caine & Steeves 2009:11).

This narrative approach, with the emphasis on stories and imagination, consists of both an epistemology and a methodology. Research based not on "data", but on story has methodological challenges. For instance, the researcher cannot pretend to be able to imagine on behalf of the participant. The researcher and the co-researcher are embodied in different contexts. They can hope for a fusion of horizons, but can never "enter" the context of the other. Through the sharing of stories, a new landscape of imaginative understanding is co-constructed. In doing this, the researcher has only three "tools", namely the telling of stories; the listening to stories, and the retelling of stories. Imagination is needed for this threefold development.

2. A DANGEROUS LOCATION

With a little imagination, one can see that this in-between land with the great variety of social interaction is a dangerous land. It is a space for new life and new development, but not without sacrifice. The development of mutations and hybrids in the ecotone space is the result of power struggles and suffering. If the practical theologian positions her-/himself in this region, this inevitably implies a choice for a kind of theology that sides with the underdog, the marginalised, and the powerless. It goes beyond the safe and powerful philosophies of the academia. This is a choice that takes us to real embodied people; it is a choice for contextuality and locality, and a choice for intervention and action. This is a choice that takes us into a reflection on, and a conversation with our African location. In other articles (2005; 2009; 2011; 2015), I have explored the postfoundational approach as a way of doing practical theology in Africa with reference to contextual themes such as HIV and Aids. This article aims to bring an aditional perspective to the argument in order to indicate how suitable a postfoundational practical theology is for the African context. Doing research in Africa brings one in conversation with liberation and feminist theologies (apart from the interdisciplinary conversation which brings political, economic and all other community issues to the table).

These theologies, which either grew out of the African soil, or found fertile ground in Africa, are like the narrative approach, voices for the unheard and marginalised stories. Working within this paradigm is a choice for the deconstruction of dominant stories and, therefore, a deliberate favouring of the "other".

A narrative approach implies a poststructural positioning. Our own stories become part of our research, which means that "knowing the self and knowing about the subject are intertwined, partial, historical local knowledges" (Richardson & St. Pierre 2005:962). This position strips away the illusion of expert knowledge and of arrogance from us. It, therefore, leaves us vulnerable and fragile (Müller 2009a). But when we embrace this weak position, it becomes our strength. Richardson and St. Pierrre (2005:962) state the following: "Nurturing our own voices releases the censorious hold of 'science writing' on our consciousness as well as the arrogance it fosters in our psyche …". This position also draws the researcher into the dynamics of an ever-changing and fluid identity. Narrative research does not leave one unchallenged or unchanged (cf. Müller 2015).

In reflection on his ethnographic journey2 with Venda people, Wilhelm van Deventer (2015) formulates this integrated approach where the self is always part of the research story, as follows:

Evolutionary changes therefore constantly take place within and between identities and cultures. This process of acculturation did however not merely occur within and between the two life and world views present in me and the Venda people, but the very same dynamics of ever-changing thought patterns, symbols and values, creative tension, reciprocal interaction, disintegration, re-integration and enrichment also takes place in the whole of one's own self.

3. PRACTICAL THEOLOGY FOR AFRICA

Doing research in Africa on contextual themes is dangerous in many ways. In my personal story, my African location provides me with safety and satisfaction, but at the same time leaves me fragile and vulnerable. As a practical theologian from Africa, I do not find myself and my research work in a safe and neutral space. That does not mean that I was or am in personal danger. But a reflection on the research journey brings me again and again to the realisation that research in this context has all kinds of challenges. Therefore, I find myself in an ongoing process of finding identity as a White, Afrikaans-speaking male researcher in Africa (see Müller & Trahar 2016). I cannot avoid a continuous reflection on my physical and emotional location. Part of this reflection is an effort to consciously and purposefully locate myself and my practical theology in Africa. Africa is my home and, therefore, my theology must be at home in Africa.

Africa is, in many ways, an in-between space, the struggle ground of the indigenous and colonial powers; the business and ecological powers; Western and African philosophies, and so on. My research on Ubuntu also brought me into the dynamic field of perceptions, expectations and biases based on culture, race, and power. In another article, I wrote about the challenges I have experienced and are still exposed to because of my whiteness and because of the colonial baggage that is always with us in Africa (Müller & Trahar 2016).

Honest reflection on issues of culture and racial biases is part and parcel of research located in Africa. Such a reflection can never be done in a neutral way. We as researchers are with our co-researchers part of the new evolving research story. A reflection should include not only our research work as if it is something outside of us. It is always about our own subjective involvement. The question is about subjective integrity, or the lack thereof. In this reflection, the ideas of liberation theology, black theology, and feminist theology can guide us. These theologies have a history of raising awareness for the position of the non-privileged and marginalised, especially in the African context.

Frostin (1988:3) refers to EATWOT3 and mentions five points in which liberation and feminist theologies differ from mainstream Western theologies:

• Social relations and not ideas are the starting point of theology. Emphasis is on the people who ask the questions. For instance, the emphasis would first be on poor people and not on poverty as an ethical issue.

• Perceptions and ideas about God concentrate on power relations. On whose side is God?

• Theology is done in a world of conflict. Issues regarding race, class, gender and wealth that create conflict have to be scrutinised.

• The previous points make it clear that theology needs new tools. Philosophy underpinning systematic theology is insufficient. Thus the methods of the social sciences have been embraced in order to study social groups, power structures, injustices, and so on.

• The organic connection between theories and praxis is highlighted, not only on an epistemic level, but also on the methodological level.

This divide between African and Western theologies is probably not as wide nowadays as it was when described by Frostin in 1988. There have certainly been many mutual influences between the various theologies in the world. In this article, I explore one such a connection point by examining some of the similarities between liberation and feminist theologies, on the one hand, and postfoundational philosophy and theology, on the other.

4. AFRICAN AND POSTFOUNDATIONAL

The postfoundational approach seems to fit well with the in-between location, since this approach forces us to first listen to the stories of people in real-life situations. It does not aim to merely describe a general context, but to confront us with a specific and concrete situation.

Without attempting to give a complete description of what is meant by the concept of postfoundationalism (Müller 2005; 2009b; 2011), the following quotation can be used to capture the essence of the paradigm. Van Huyssteen translated the postfoundational philosophy into a postfoundational theology:

… a postfoundationalist theology wants to make two moves. First, it fully acknowledges contextuality, the epistemically crucial role of interpreted experience, and the way that tradition shapes the epistemic and nonepistemic values that inform our reflection about God and what some of us believe to be God's presence in this world. At the same time, however, a postfoundationalist notion of rationality in theological reflection claims to point creatively beyond the confines of the local community, group, or culture towards a plausible form of interdisciplinary conversation (Bold - J.M.) (Van Huyssteen 1997:4).

According to Van Huyssteen (2006:10), "… embodied persons, and not abstract beliefs, should be seen as the locus of rationality. We, as rational agents, are thus always socially and contextually embedded".

This way of thinking is always concrete, local, and contextual and simultaneously reaches beyond local contexts to transdisciplinary concerns. It is contextual and simultaneously acknowledges the way in which our epistemologies are shaped by tradition. Van Huyssteen (2006:22) refers to the postfoundationalist notion as "a form of compelling knowledge", which is a way of seeking a balance between "the way our beliefs are anchored in interpreted experience, and the broader networks of beliefs in which our rationally compelling experiences are already embedded".

It is interesting to note that we find the same language in the narrative approach, in liberation and feminist theology, and in postfoundational philosophy and theology. It is a language that emphasises:

• The local context as the prime source of knowledge;

• The stories of the marginalised;

• Transdisciplinary rationality, and

• Real people instead of general phenomena.

This language helps us connect to both the local and the general; to Africa and the West; to the small and the big; to the context and traditions of interpretation; to practical theology as a sophisticated academic field, and the doing of Theology in the dust of Africa. This language allows not only the telling of stories, but also the process of storying, because our own stories (both the researcher's and the co-researcher's story) are always intertwined with the emerging research story.

4.1 Ubuntu research - a case study

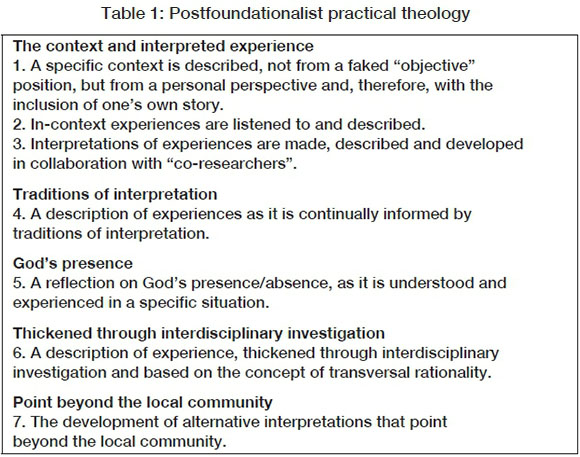

What follows is an attempt to move from a postfoundational philosophy to a postfoundational practical theological epistemology and methodology. I have converted the key concepts in the quotation above into a seven-phase movement for the doing of practical theology. A specific research project (Ubuntu) is then used as an example or case study to illustrate the "seven movements" as a research structure for practical theology (cf. Müller 2005; 2009a; 2009b; 2011).

4.2 Postfoundational research made practical for a specific Ubuntu research project

The Ubuntu research project, located at the Centre for the Advancement of Scholarship (CAS), University of Pretoria, is taken as a case study. The practical theological section of this research project (one of the so-called clusters) was planned and is currently being conducted on the basis of the "seven movements". The following is a very brief outline of this section (Cluster 2) of the project.

4.2.1 A specific context is described

The context/action field/habitus of this research can be described as the post-conflict contexts in South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Kenya. The co- researchers, who are living and working within the different contexts, are encouraged to tell the story integrated with their own personal story. This method can be referred to as ethnography. Ethnography as an epistemology is in line with the narrative understanding of knowledge and the creation of knowledge (see Bochner & Ellis 1996). It is autobiography embedded in the cultural and contextual story and as such it is an integral part of this postfoundational approach.

4.2.2 In-context experiences are listened to and described

The team of researchers does empirical research, based on the narrative approach. They do fieldwork and employ various methods to listen to the stories of specific people in different situations. Perceptions, expectations, general understanding, or action-narratives that might be informed by the Ubuntu discourse are listened to and recorded.

4.2.3 Interpretations of experiences are made, described and developed in collaboration with 'co-researchers'

Post-foundational researchers do not perceive themselves as the best interpreters of "data", but rather as facilitators of interpretation. Instead of trying to reach one-sided conclusions, they are primarily interested in their co-researchers' own interpretations and formulations regarding Ubuntu. They listen carefully and formulate tentatively, while they remain in discussion with their co-researchers.

4.2.4 A description of experiences as it is continually informed by traditions of interpretation

There are specific discourses/traditions in certain communities that inform perceptions and behaviour. The Ubuntu story is rich and diverse. A great deal has been written about the concept. The researchers are curious about these discourses and will attempt to gain some understanding of how current behaviour is influenced by historically based beliefs, perceptions and habits, and how these are linked to the Ubuntu discourse.

4.2.5 A reflection on experiences of God's presence/ absence in a specific context

Without introducing God language into the research conversation, there is an alertness to the way in which people interpret their situation in view of their understanding of the ultimate questions of life. The researchers are interested in their conversational partners' possible spiritual understanding of Ubuntu. They will try to introduce God talk in a spontaneous and organic way and listen carefully to the responses of the co-researchers.

4.2.6 A description of experience, thickened through interdisciplinary investigation

Ubuntu, like all philosophies, is not an isolated entity. It is part of a dynamic network of ideas, discourses, and cultures. Research on Ubuntu can, therefore, not be done in isolation. It needs to be explored in its relation to other issues such as race, gender, ability and disability, and space. Interdisciplinary work is complex and difficult, but part and parcel of the postfoundational approach. It is a challenging phase of the research, because language, reasoning strategies, contexts, and ways of accounting for human experience differ greatly between the various disciplines (Midali 2000:262). The ideal is, therefore, a trans‑disciplinary approach (cf. Müller 2009a), which includes the insights of scholars from various disciplines on the basis of transversal rationality. The starting point for this interpretation is always a very specific, local, concrete narrative, which is taken from the narratives recorded by the researcher.

4.2.7 The development of alternative interpretations that point beyond the local community

Generalisations are avoided, because with every generalisation the particular meaning within a certain context becomes blurred. Specific interpretations are tentatively formulated for a specific context. But the question of what this might mean for other, different contexts is also taken seriously and reflected upon. The presence or absence of Ubuntu in a certain location does not necessarily say anything about other contexts. But it might say something that can be of use to others, and the research will not be complete without entertaining these questions.

5. CONCLUSION

The narrative approach asks for a creative and imaginative ending. The telling of the different stories needs to develop into a retelling, which will, it is hoped, provide new insights and understanding. When we try to interpret old and distant concepts into current contexts and to make sense of past stories and find the meaning thereof for the present, we are actually trying to converge different horizons. Thinking about Ubuntu and the way in which it can or should be integrated into present society entails a hermeneutical process. It "aims at a mutual dialogue in the etymological sense of dia‑ legein: welcoming the difference in order to learn from it" (Kearney 1988:38). Research is never complete without such a hermeneutical process. We come to a logical ending when we are able to allow and welcome the difference and learn from it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Browning, D. 1991. A fundamental practical theology. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Bochner, A.P. & Ellis, C. 1996. Talking over ethnography. In: C. Ellis & A.P. Bochner (eds.), Composing ethnography: Alternative forms of qualitative writing (London: Sage), pp. 13-45. [ Links ]

Caine, V. & Steeves, P. 2009. Imagining and playfulness in narrative inquiry. International Journal of Education and the Arts 10(25):1-14. [ Links ]

Frostin, P. 1988. Liberation theology in Tanzania and South Africa: A first‑world interpretation. Lund: Lund University Press. [ Links ]

Heitink, G. 1993. Practical theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Kearney, R. 1988. The wake of imagination. London: Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203430620. [ Links ]

Midali, M. 2000. Practical theology: Historical development of its foundational and scientific character. Rome: Libreria Ateneo Salesiano. [ Links ]

Müller, J.C. 2005. A postfoundationalist, HIV-positive practical theology. Practical Theology in South Africa 20(2):72-88. [ Links ]

Müller, J.C. 2009a. Transversal rationality as a practical way of doing interdisciplinary work, with HIV and AIDS as a case study. Practical Theology in South Africa 24(2):199-228. [ Links ]

Müller, J.C. 2009b. Practical theology: A safe but fragile space. Paper presented at the Joint Conferences of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, University of Stellenbosch, 23 June. [ Links ]

Müller, J.C. 2011. Postfoundational practical theology for a time of transition. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 67(1), Art. #837. doi.10.4102/hts.v67i1.837. [ Links ]

Müller, J.C. 2015. Exploring 'nostalgia' and 'imagination' for Ubuntu research: A postfoundational perspective. Verbum et Ecclesia 36(2). doi: 10.4102/ve.v36i2.1432. [ Links ]

Müller, J.C. & Trahar, S. 2016. Facing our whiteness in doing ubuntu research. Finding spatial justice for the researcher. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72(1):page numbers? [ Links ]

Richardson, L. & St. Pierre, E.E. 2005. Writing. A method of inquiry. In: N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 3rd ed (London: Sage), pp. 959-977. [ Links ]

Van Deventer, W. 2015. Vhuthu in the muta: A practical theologian's autoethnographic journey. Verbum et Ecclesia 36(2), 8 pages. doi: 10.4102/ve.v36i2.1435. [Online.] Available at: http://verbumetecclesia.org.za/index.php/VE/article/view/1435> [2017, 15 May]. [ Links ]

Van Huyssteen, J.W. 1997. Essays in postfoundational theology. Grand Rapids, MI.: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Van Huyssteen, J.W. 2006. Alone in the world? Human uniqueness in science and theology. The Gifford lectures. Grand Rapids, MI.: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

1 The essence of this article was originally presented as a paper at the Roundtable discussion, International Academy of Practical Theology 15-20 July 2015, Pretoria.

2 Later in the article, I will discuss the relation between the postfoundational paradigm and ethnographic epistemology and methodology.

3 Ecumenical Association of Third-World Theologians.