Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.37 n.1 Bloemfontein 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v37i1.5

ARTICLE HEADING

The narrative of the woman caught in adultery (Jn 7:53-8:1-11) re-read in the Nigerian context

Prof. C.U. ManusI; Dr. J.C. UkagaII

IDept. of Theology and Religious Studies, National University of Lesotho, Lesotho

IIDept. of Philosophy and Religions, University of Benin, Nigeria

ABSTRACT

This article draws on the spirit and letters of the Vienna Declaration and its Program of Action that emanated from the World Conference on Human Rights held in 1993. It delineates the fact that Women's rights are essential aspects of the fundamental human rights of every individual. With the synchronic study of the receivers as our methodology, we expose the narrative of the unnamed adulteress woman in John 7:53-8:1-11, in order to seek a theological grounding for women's human rights in the context of Nigeria, where Boko Haram's dehumanization of the Chibok girls and other women is rife, and explore the Nigerian history of women activists. We exegetically expose the storyline of the text of John and contrast the ideas with the horrific incidence of women's degradation in Nigeria. The findings reveal abiding lessons adjudged relevant for a sustainable pro-life Christology and theology of the rescue and liberation of women from militant jihadists in north-eastern Nigeria. For Jesus, women are divinely blessed with equal rights with men.

Keywords: Abduction; Adulteress; Marginalization; Human rights; Pro-life

Trefwoorde: Ontvoering, Egbreekster, Marginalisering, Menseregte, Pro-lewe

1. INTRODUCTION

Scholars agree that, since the Beijing Conference (1995), there is a more serious focus on recent discourse on women's rights,1 due mainly to the domination, oppression, subordination and exploitation of women in overtly patriarchal societies (Uchem 2001:93, 114-119). In such societies, Nigeria inclusive, human rights were regarded as "property" only for men (Manus 2010a: 1-2). On this subject matter, Lasebikan noted the following:

The issue of women's rights [has] emerged much more forcefully in the last half a century in Europe and now in the two-thirds world with pressure groups asking for more of the empowerment of women (Lasebikan 2001:11).

She further observed that

[i]n many parts of Nigeria, religious differences notwithstanding, women do not enjoy equal rights with men as far as family land inheritance is concerned. Only very few women are economically strong enough to purchase a parcel of land on their own while many land owners refuse sale of land to women for reasons best known to them (Lasebikan 2001:13).

Along these lines of thinking, we must add the horrendous abductions of women and girls by Boko Haram2 jihadists in north-eastern Nigeria as well as reveal to the reader one of the most heated debates being entertained on the vexed and contentious issue of child marriage in Nigeria. The latter debate arose as a result of the marriage of a 13-year-old Egyptian girl-child contracted by a Nigerian Muslim Senator, Yerima (50), which the Churches and various women pressure groups3 have out-rightly condemned as a total violation of the girl's human rights. In spite of the Senate's tacit support to approve 13 as a marriageable age for girls in Nigeria, many considered this an action against civil liberties and "basic morality" (Fani-Kayode 2013:16).

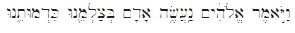

In the Bible, all human beings are created equal before God who has so lavished his "image and likeness", as is written in Genesis 1:26:

Then God said, "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness" (RSV).

This is God's gratuitous gift to all humanity as the spiritus creator (Manus 2010a:8). Although some Biblical stories depict the creation of women after men, several other biblical passages indicate that the rights of women are in God's mind (Okure 1988). Oduyoye, one of Africa's foremost feminist theologians, has amply asserted that such stories indicate that "human rights are women's rights as well" (Oduyoye 2001:2-4). It is this insistence on the part of women in the face of continuing denials of women's rights that has caused activist women leaders in Nigeria to raise their voices against the exploitation, marginalization and depersonalization of women in both church and society (Manus 2002:65-68).

With regard to the woman in the text under discussion, we wish to agree with Schussler Fiorenza that what the Scribes and the Pharisees had done to the adulteress woman definitely reflects the demand of the dominant patriarchal and religious ethos and praxis of the Jewish people (Schussler Fiorenza 1983b:140-143). The central aim of our paper is to involve us in the critical quest for women's rights as persons of faith. For us, there are abiding lessons from the text, which suppose that, in spite of the maleness of Jesus, his ministry is women-friendly (Harris 1991:100- 111). Uchem (2001:148-150) observes that one manifests inclusiveness in the family of God. In this study, we adopt the synchronic study of the receiver. This involves

a focus on the social, religious, political and economic conditions of the context within which the text of (Jn 7:53-8:1-11) is being interpreted (Manus 2007:859 n. 1).

In addition, we use the feminist hermeneutical approach, in order to process the discussion on our findings (Bateye 2010:226). The purpose is to galvanize our audience (usually men) to critically begin to reflect theologically on women's rights in the context of the call for gender justice and equity in the wake of terrorist kidnaps and abductions in Nigeria. If this optimism is convincing and many other theologians share and supplement the views being expressed, this article would have made an appreciable impact on the community of theologians of the Nigerian Christianity.

1.1 The historical background of the text

Dating from the fourth century, early Christian tradition has preserved this illustrative and didactic story in some New Testament manuscripts. Both internal and historical evidence abound to support the view that the narrative did not belong to the Fourth evangelist's composition. As Shepherd notes, the reason for this is that the story "does not appear in the oldest and best manuscripts and is apparently a later interpolation" (Shepherd 1971:718). Along this line of thinking, commentators agree that the earliest and best manuscripts of the Gospel of John glaringly do not bear the story (Schnackenburg 1968; Brown 1970; Bultmann 1971). In some of the later manuscripts of the Gospel of John, the story is located in different places, sometimes after 7:36, 7:44, and 21:25. In some manuscript traditions, the hallowed story has become so ubiquitous to the extent that it is also found in the Third Gospel (Luke) after 21:38 and 24:53.

The text attests that, as early as 125 CE, the story had already been received into Christian tradition. Textually speaking, the story of the woman caught in adultery confirms that the connection between scripture, that is, between what is written as tradition and what is handed down, is not so clear-cut. This means that the story was transmitted in the early church and, due to the great approbation it had received in many of the nascent churches, it later became qualified to be inserted at various points in some of the New Testament books. We wish to agree with many critics that the story, "though not an original part of this gospel" (Boring- Craddock 2009:314), "need not be taken as an unauthentic tradition about Jesus" (Shepherd 1971:718). Schussler Fiorenza adds voice to this view when she writes:

Although the story about the woman caught in adultery is a later addition to the Gospel's text, the interpolator nevertheless had a fine sense for the dynamics of the narrative which places women at crucial points of development and confrontation, namely the pre-eminence of women in the Johannine community (Schussler Fiorenza 1983b:326).

While the passage does not manifest the usual Johannine compositional techniques, it is clothed in the garb of the Synoptic Gospels' pronouncement stories, where Jesus is depicted as

one who came to seek and to save the lost, not to condemn men (and women) but to offer them God's forgiveness and acceptance (Shepherd 1971:718).

The story parallels Mark 12:13-17 (Paying taxes to Caesar), where the Pharisees and the Herodians put Jesus to the test. Jesus tactfully obviates the machinations of those "thugs" with a memorable and sapiential concluding pronouncement: "Give to Caesar what is Caesar's and to God what is God's" (Mk 12:17) (Stein 2001). Johannine scholars such as Boring and Craddock agree that

[t]he story is lacking in Johannine features but resembles the pronouncement stories of the Synoptic Gospels that narrate the attempts of Jesus' opponents to entrap him, which Jesus frustrates by a memorable and wise concluding pronouncement (see, Mark 12:13-17) (Boring & Craddock 2009:315).

In this instance, we draw from the comments on Johannine scholarship from Prof. Johannes Beutler, one of the foremost German Johannine scholars, who, in his latest commentary on John, amplifies:

The pericope about Jesus and the woman taken in adultery appears like a meteorite in the narrative flow of John's gospel. The passage interrupts the dialogues between Jesus and the "Jews" in the temple area of Jerusalem. The theme appears unusual for John's gospel. Jesus' behaviour is different from that which he displays in the chapters before and after this incident. Jesus restrains himself and begins to speak only at the end of the episode. The literary form of the section is that of the so-called paradigm or apothegm, a genre rarely attested in John. Within the narrative, characters appear who are otherwise not encountered in John's gospel, such as the "scribes" (Jn 8,3). The style is not really Johannine. The gentleness of Jesus causes one to think of that same quality which he shows in Luke (one thinks of the story of Jesus and the woman who was a sinner in Lk 7,36-50). In the early centuries, the attestation of the text is poor and its place in the order of the text inconsistent. Thus, we are confronted with the problem of the text's authenticity. On the other hand, the Council of Trent declared that the disputed sections of the New Testament are fully part of it and confirmed their canonicity and inspiration (DS 1504) (Beutler 2017:84).

Mainline Johannine commentators accept that, while John's Gospel is not literarily exactly like the earlier gospels, it had some interaction with the Synoptic tradition and in itself reflects in its own way historical traditions that are rooted in the circumstances of Jesus' own life and times (Anderson et al. 2016). In light of the opinio consensus on the foreign face of the narrative on the adulteress woman in John 8:1-11 and given the insight into the text's transmission history sketched earlier, we agree that the text is spuriously interpolated into the present place it occupies in the Gospel. Thus the story reflects a Lukan composition uncritically appended by a Christian evangelist in the third half of the second century of the Christian Church who knew well of the Johannine tradition of Jesus' life-affirming stance.

To conclude this section, many modern textual critics have identified six different places where the story is located in other New Testament manuscripts. They have testified that, in such locations, the story had been marked with obelisk, that is, - or + symbols used in ancient manuscripts, to mark a text or passage of a reasonably doubtful authenticity, especially one suspected of being a secondary addition (Beutler 2017:85). John 7:53-8:1-11 reflects an instance of the revision, editing and re-writing by the custodians of orthodoxy in accordance with their tenets as they had been commissioned by Constantine the Great in the fourth century of the Common Era. Some scholars have, along this line of reasoning, noted that the sole aim is to confer on Jesus the unique status he has continued to enjoy ever since (Komoszewiski et al. 2006:103-104).

1.2 Context of interpretation

In this section, we wish to explore briefly both the historical and modern roles some women have played and still fulfil in Nigerian society. Our objective is to show how the impact they have made and still make can provide us with the basis to re‑read John 7:53 and 8:1-11, in order to sketch Jesus' pro-life stance and its relevance for contemporary women. Having said this, we consider the discussion of the "ancient and modern" activism of women as "a crucial interpretative matrix" (LeMarquand 2004:84), from which insight we process our exegesis of the text.

There is no doubt that, in the history of African humankind, women made and still continue to make very significant contributions to the development of family, church and the defence of women's rights in society. In Nigeria, names of such distinguished women figures abound. The heroic roles played by Olori Moremi Ajasoro, Queen of the Ile-Ife Kingdom, cannot be easily erased from the memory of the Yoruba people of Nigeria (Akintunde 2001:89).

To add to this catalogue of valiant women, history records the activities of Queen Amina of Zaria (1533) as the Hausa Muslim warrior of Zazzau. There were other women of substance such as Margaret Ekpo (1914-2006) of Calabar in the present Cross River State, Nigeria. She functioned as a women's rights activist, a social mobilizer and a pioneer female politician in the First Republic of Nigeria. We also mention in this category Madam Funmilayo Ransome Kuti, whose political activism and opposition to indiscriminate taxation of women by the British colonial masters led her to be rated as the doyen of women's rights in Nigeria as well as "The Mother of Africa".

It is pertinent to inform readers that several other women have blessed the Nigerian project with rare talents and special gifts as daughters and mothers of the land. In recent times, the likes of late Dora Akunyili, former Federal Minister of Information and author of Re‑branding the Nigeria Agenda; Oby Ezekwesili, former Deputy President of the World Bank and vanguard for "Bring Back Our Girls" from the Boko Haram kidnap; Grace Alelli Williams, the first Nigerian woman Vice-Chancellor of a Federal University (Uni-Ben), and Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, former Nigerian Minister of Finance and Economic Planning. It is well known that these women draw attention to the calibre of African womenfolk who have displayed rare talents in their services to humanity, as they have distinguished themselves as top-class breeds in both politics and the civil service in the Nigerian context.

Similarly, in the religious sphere, many women of the Nigeria Conference of Women Religions (NCWR) have demonstrated proven charismata as excellent "Mother Generals" and Novice Mistresses. Many of them have led their congregations as successful human resources managers. They have provided unstinted leadership qualities that have helped them lead tens of thousands of women in various religious communities in Nigeria.

However, despite this increasing rise in the status of some women in African society and church, the Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI noted the following:

While it is undeniable that in certain African countries progress has been made towards the advancement of women and their education, it remains the case that, overall, women's dignity and rights as well as their essential contributions to the family and to society have not been fully acknowledged or appreciated. Thus women and girls are afforded fewer opportunities than men and boys. There are still too many practices that debase and degrade women in the name of ancestral tradition (Pope Benedict XVI 2011:31).

In light of this incompatible situation, our article attempts to explore the story transmitted in John 7:53-8:1-11, in order to expose how Jesus, the Lord of the Church, has acknowledged the sacrosanctity of the humanity of the woman in the story and how he effects her liberation from the clutches of the representatives of death.

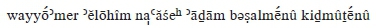

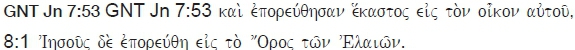

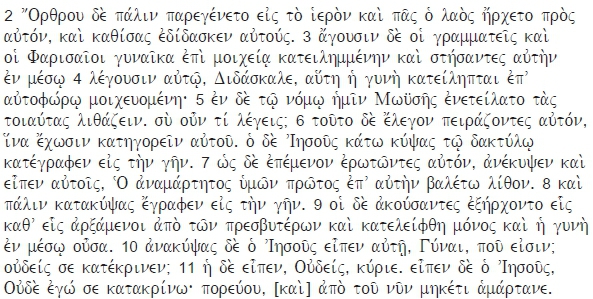

2. THE TEXT

NAB John 7:53 Then each went to his own house, 8:1 while Jesus went to the Mount of Olives. 2 But early in the morning he arrived again in the temple area, and all the people started coming to him, and he sat down and taught them. 3 Then the scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery and made her stand in the middle. 4 They said to him, "Teacher, this woman was caught in the very act of committing adultery. 5 Now in the law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. So what do you say?" 6 They said this to test him, so that they could have some charge to bring against him. Jesus bent down and began to write on the ground with his finger. 7 But when they continued asking him, he straightened up and said to them, "Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her." 8 Again he bent down and wrote on the ground. 9 And in response, they went away one by one, beginning with the elders. So he was left alone with the woman before him. 10 Then Jesus straightened up and said to her, "Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?" 11 She replied, "No one, sir." Then Jesus said, "Neither do I condemn you. Go, (and) from now on do not sin anymore."

2.1 The content analysis of the text

It is expedient to present a content analysis of the text in the exegetical process. The reason for this is that the strength and viability of the content of a text is determined by the quality of its textual foundation; the flow of the argument will help our interpretation so that it will not be derived from a faulty or defective foundation. This is done so that the quality of our exegesis will be determined by its foundation and the guiding principles such as "the syntactical relationships of the various words and word groups" (Fee 2002:41) amenable for African contextual exegesis (Manus 2003; Mundele 2012). Where possible, the local vernacular may be employed, in order to facilitate easy comprehension of some of the words and clauses in this stunning story by "ordinary readers" of the passage in many of Nigeria's local churches.

Verses 7:53-8:1-2 - The exit scene.

• Every follower went home

• Jesus went to Mount Olives

• Early next morning, Jesus went to the Temple area.

• All the people went out to Jesus.

• He sat down and taught them. What? Perhaps about the Law?

Verse 8:3-6b - The question of the Scribes and the Pharisees - accusers of a woman, a non-definite person is recounted, but in the form of a story. In this instance, it is a case of the use of a representative figure usually considered Johannine.

• Alleged that the woman was caught in the very act of adultery.

• Compelled her to stand in the middle "to face the gun".

• The accusers addressed Jesus as Teacher.

• They reminded Jesus that the Law of Moses prescribed stoning such a woman to death.

• They asked Jesus: what his "own take" on the issue was?

• Verse 6: the narrator's comment: the Testmotif usually the evangelists'literary art to test Jesus so as to put him into trouble as in Mark 12:13-17.

Verses 6c-8 - Jesus' reaction. Jesus' response seems to be a Yes/No option. The stages are as follows:

• Jesus writes on the ground (v. 6b).

• The accusers depart one by one beginning with the elders.

• Jesus is left alone.

• The woman stands before him, also alone.

Verses 9-11 - The conclusion of the narrative.

• Jesus strengthens up, yawned, perhaps sighed and groaned, that is, kwee ude, nyaa ngu, and asked: Nwanyi: woman, where are they who have accused you?

• Again, Jesus groaned and asked: where are your accusers? (v. 10)

• Have they not condemned you?

• No one, my Lord (sir).

• Jesus said to her: shee, na mi go condemn you? Tu fia kwa! (Habah, am I the one to condemn you? God forbid!)

• Lawa! (go), site taa, emekwela njo ozo (from henceforth do not sin again).4

2.2 Exegesis of the text (John 7:53-8:1-11)

We will attempt to interpret the text according to its present form in the canon. Much as we agree that the insertion of the passage in its present place is arbitrary, it also makes significant sense in terms of the importance of women in John. Indeed, John's Gospel has other stories of women who, after their encounter with Jesus, became disciples, such as the Samaritan woman (Jn 4:7-42) and Mary Magdalene (Jn 20:11-18), or those with whom Jesus is connected through family friendship, such as Mary and Martha, the sisters of Lazarus, his friend who lived in Bethany, four miles from Jerusalem (Jn 11:1-44). Even if the story of the adulteress woman seems bizarre, it fits the positive image of women in John's Gospel (Beutler 2017:84). Our exegesis bears us out. In light of its narrative criteria, the construction of the passage is structured and exposed as follows: verses 7:53-8:1-2; verse 8:3-6b; verses 6c-8, and verses 9-11.

2.2.1 Verses 7:53-8:1-2

This short unit introduces the scene and the characters. It provides a going- out and going-in scene. Jesus' conversation partners return home, because every "listener" to Jesus went home to his/her own house (v. 7:53). Like the other people, Jesus himself left Mount Olives, located on the eastern side of Jerusalem. Early the next day, he went to the Temple ground. Once more, all the people joined him. It has been noted that this movement description belongs to Johannine sets of language and imagery, which the evangelist adopted as a literary and fundamental theological Leitmotif to help the reader concretize the understanding of his Gospel (Humble 2016:220). After the detour, he sits down. This is expressed in the aorist participle form that is used to stress the action. The point of action of the verb kaqizw as an ingressive or inceptive aorist supposes that Jesus took his seat and then taught the people, as indicated by evdi,dasken in the imperfect mood (Zerwick-Grosvenor 1979:xii-xiii).

What might have been the content of his teaching? The evangelist remains silent on that subject. His silence supposes that the earliest listeners cherished what they were being taught; something special was "going out" of the Mosaic Law and "going into" the new family of God. In short, Jesus, the prophet of whom Moses had spoken, "re-branded" the erstwhile legal code. For the accusers, namely the "Scribes and Pharisees", the legal exponents during the Second Temple Judaism, Jesus was probably re‑formatting some aspects of the stipulations of the Torah. His action might have challenged them to put to him the question of the state of the adulteress woman vis‑à‑vis the dictates of the Law.

On the literary and compositional technique reflected in the text, the association of Jesus with the overnight stopover at Mount Olives is a typical Lukan portraiture. On the basis of this and judging from Luke 7:37-50, the story of the encounter of the sinful but repentant woman at Simon the Pharisee's home banquet, Johannine critics as well as Beutler consider the passage a Lukan invention. This goes a long way to explain why the story is found in Luke 21:38/Luke 24:53 in some New Testament manuscripts. On this point, we briefly identify the insights provided by some Johannine exegetes (Becker 1963; Schnackenburg 1988. Derret 1995).

2.2.2 Verses 8:3-6b

In this instance, the actors are the "Scribes and Pharisees", two orthodox protagonists of the Law of Moses and representatives of the dominant patriarchal culture. They accost Jesus. According to the Old Testament tradition enshrined in Leviticus 20:10 and Deuteronomy 17:5-7, 19:15-21 and 22:22-27, for the sin of adultery, both the man and the woman were to be stoned to death and the accusers were not to be malicious in their allegation (Deut 19:16-19). In the social political history of Palestine in Jesus' time, the Romans denied the subject peoples the ius gladii - the right to kill with the sword (Manus 1999:11-28). In Mark 12:13-17, the test on paying taxes to Caesar, put to Jesus by the Pharisees and the Herodians who had also addressed him as Teacher (v. 14),5 stresses the fact that, while Jewish tradition prescribed the death penalty, the Romans had abrogated this and reserved the right to themselves. This time, the test of the Scribes and Pharisees to Jesus could be paraphrased as follows: if you are the Messiah of Israel (understood in its political sense), would you allow us, your brethren, the Jews, to obey the Mosaic stipulation or the Roman colonial edict? The questioners knew that any unguarded statement on the matter would put Jesus into trouble with both the patriarchal and the colonial establishments. On the part of Jesus, silence was the best answer to the fools. They left, beginning with the elders who should have provided better counsel; instead, they let themselves down and "chickened out"

, one by one, from the scene like pariahs. This is the first case where the "Scribes and Pharisees" are encountered in John's Gospel, and it is

, one by one, from the scene like pariahs. This is the first case where the "Scribes and Pharisees" are encountered in John's Gospel, and it is

the strongest indication of the non-Johannine origin of the story. The Fourth Gospel speaks rather of "chief priests and Pharisees" (see 7:45) (Beutler 2017:87).

2.2.3 Verse 6

0 δε’Ιησούς κατώ κύψας τώ δακτύλώ κατεγραφεν είς τňν γňν is somewhat enigmatic. Jesus bent down to write or to draw something on the ground with his finger. This has remained a crux interpretum. Does this indicate that Jesus knew how to write and read. In other words: Was he literate? Was he simply waiting for the "accusers" to disperse? Was he indecisive? In this instance, Jesus' action reflects a notable Lukan phrase: εν δακτύλώ θεού:"by the finger of God". This is literarily close to Luke 11:20, which has been defined as a Lukan "symbolic expression of the mystery of Jesus' power in what God was doing through him" to save life and not to destroy (Manus 2010b:25).

The majority of commentators also view the expression en daktulo Theou - the finger of God as a Lukan creation that differs substantially from Matthew's "Spirit of God". Because of the absence of the enigmatic expression in Matthew, Gundry accepts the Lukan text as similar to the presence of a number of Mattheanisms in the First Gospel (Gundry 1982:230). Other critics' arguments are based on the fact that what is transmitted in a parallel passage in Matthew 12:28 is en pneumati Theou - the Spirit of God, which is un-Matthean; therefore, en daktulo Theou is Lukan. Williams argues that Luke uses the "finger" to signify "a picture of the Spirit", because Luke is known to be the evangelist of the spirit (Menzies 1994; Williams 2003:46). In this narrative, are we really confronted with Lukan omission, substitution, re-interpretation or loyalty to the traditional legend or source? The ensuing discussion can help us establish some convincing and reliable information on this critical issue.

There is no doubt that the saying is archaic, given the absence of such a phrase in Mark, which is generally considered to be the first Gospel and the one used by the Synoptists (Mk 3:23-27). We identify three other notable logia in the Lukan tradition whose significance mirrors the superhuman dunamis wrought by Jesus during his ministry. The sayings all stress the demonstration of Jesus' superhuman power. They are sandwiched within the context of the exorcisms performed by Jesus, namely the Blasphemy against the Holy Spirit in Luke 11:18‑19 and parallels, the dealing with Beelzebul in Luke 11:21‑22, and the Binding of the strong man in Luke 11:21‑23. In these three passages, including the text under study, Jesus is depicted as mightily doing battle against the demonic forces that frustrate human life.

Were the battles waged manually? How can Christians in Nigeria, where many people's worldviews are believed to be nearly identical with those of the Jews, understand this mysterious statement? It is hoped that the bizarre expression, finger of God, was not borrowed from ancient Egyptian esoteric and apocryphal oracular work The Six and Seven Books of Moses usually associated with magical conjurations and invocations by demon worshippers and believers in occult practices in many states of Nigeria. We may better understand what is meant if we forcefully interpret Luke 11:15, where Jesus' power to do exorcism is ascribed to Beelzebul. For us, the finger of God may expediently best be taken as superhuman power invested in Jesus by God, in order to usher in the reign of God in human society.

We note that, in response to his critics, Jesus makes an ad hominem argument (vv. 17-19). He retorts by asserting that the fact that Jewish people of that time practised magical exorcisms is not a sufficient reason to accuse him of being a magician. Jesus makes the Pharisees realise that it was grossly illogical to conclude that Jesus performed his exorcisms through the power of demons. If he belonged to the demonic household, the critics should have realized that "division leads to destruction". As such, there would be no unity in the occult household (Williams 2003:46). Perkins pertinently concurs:

In Jesus' view it is totally illogical for the prince of demons to drive out demons and thereby erode his own power. It is tantamount to civil war (2004:128).

According to her, Jesus' finger is not that of Moses who wrote on a tablet of stones, but in the heart of living sons and daughters of Abraham inviting them for a change of heart (Perkins 2004:128, 161; Funk 1990:76). For us, the idea of the power in Jesus' finger accords well with the spirit of the thanksgiving hymn of the Psalmist:

the Lord's right hand has done mighty deeds,

his right hand is exalted.

The Lord's right hand has done mighty deeds.

I shall not die, I shall live and recount

the deed of the Lord (Ps. 118:15c-17).

Inspired by the Old Testament categories such as the above, Luke makes Jesus deny that his source of power is from the type that his Jewish contemporaries employ. In sum, Luke is, in this unit, telling his audience as well as the Jewish religious leaders that Jesus performs his own exorcisms by the "finger of God"; that is, by a direct intervention of God, in order to herald "the Kingdom of God that has come" to them (Talbert 1984:137).

The woman's silence

From verses 6b to 9, the silence of the accused woman pervades. There is no doubt that she remained silent to respect the Jewish legal prescription that demanded women to be speechless in the presence of men. She remains silent to avoid being accused of another transgression, namely by engaging in an argument with men, she could quickly be arraigned for commission of erwat dabar; something indecent in her, prescribed in Deuteronomy 24:1-4, that could easily be used by her accusers to get her dismissed from her husband's house. Besides, she believed that if she were to engage in self-defence before the men, especially if she were to ask about the trail meted to her partner in crime, the hawk-looking and wild patriarchs who, due largely to their own conception of sin in Jewish religious tradition and their bias as religious leaders against women, point accusing fingers at the failings of human beings, would insist on the likelihood of her death. Besides, who was she to pontificate on the interpretation of the

Law, of which the majority of her generation and herself were deprived of, due to their socialization? The fear of death hangs over her mind and compels her to prefer silence. Claassens cogently draws our attention to the dehumanization to which women are exposed, according to some Old Testament narratives and vice versa (Claassens 2016:180-190).

Jesus' silence

When the woman's accusers depart, Jesus breaks the silence of the woman as he affords her the opportunity to speak out. She speaks before Jesus, a rather considerate Jewish man, as did the Samaritan woman at Jacob's well in John 4:2-42. Jesus interprets the Jewish law to her, but desists being judgemental. Jesus' silence is not due to the fact that he fears being accused of complicity in the case. Rather, his attitude confers a re-evaluation of the case brought to him by the religious leaders who would have alleged: Moses commands us to stone such a woman to death, but the Romans commands us not to: what do you say? His silence is not to re-affirm the Roman maxim: qui tacet consentiret, but to warn his contemporaries that they misuse and abuse the prevailing law which they take as a support to waste life, especially that of a woman, a daughter of Abraham for that matter. He chooses to remain silent as a demonstration of his non-acceptance of their interpretation of the law. By bending down, being silent and writing on the ground, Jesus rejects the interpretation of the Mosaic Law by the patriarchs of his time.

In sum, we observe that Jesus' silence was to capsize the spirit of the case before him. While the religious authorities silence the woman, because she does not obey the interpretation and the adjudication of the law they offer, Jesus blocked them by his silence, because they are biased in their interpretation, as they fail to consider the value of the human being. By his silence, Jesus re‑brands both the law of his time and the contemporary Jewish culture. His counsel to the woman empowers her to share with him the obnoxious nature of traditional Jewish culture that approves the silence and domination of the majority of Jewish women in the presence of men. In this instance, we agree with several recent authors that, in John, Jesus is portrayed as beyond the Law and as a new revelation of God's will on earth (Wendel & Miller 2016).

Jesus' writing on the ground

What exactly did Jesus write on the sands of life with his finger? We wish to identify with Beutler's exegetical comments that help us fathom what Jesus writes on the ground.

Jesus bends down and writes with his finger on the ground; the woman's accusers insist that he give an answer. Thereupon, Jesus bends down again and writes on the ground. What is the meaning of this action with Jesus writing on the ground? Still today, exegetes ask about the text which Jesus, perhaps, was writing on the ground. Jer 17,13 is often suggested as the text: "Those who turn away from you shall be written in the earth, for they have forsaken the Lord, the fountain of living water". The saying is addressed to Israel. Thus Jesus would be referring to the judgement that the prophet is proclaiming for all who turn away from the Lord. However, this proposal remains purely speculative. We have to acknowledge that we do not know what Jesus was writing on the ground. If the text says nothing about it, one has the impression that the content is scarcely of importance (Beutler 2017:88).

According to Beutler, O'Loughlin (2000, cited in Beutler 2017:88) draws our attention to the significance that Augustine, the Bishop of Hippo, suggests for this action. He notes a semantic opposition between Jesus' writing on the earth and the writing of the Decalogue on stone as the basis for the accusation against the woman. This comparison seems convincing in view of the fact that the Law of Moses may not be used as a rigid instrument of execution. One must write in the sand, handle the situation flexibly, and have regard for the condition of the people to whom the Law is being applied. In this case, what is relevant is that the accusers are themselves involved in sin. Whoever is without sin (a hapax in the New Testament), let him be the first to cast a stone at her (Beutler 2017:88).

For contextual relevance and together with Mligo, a Tanzanian Johannine scholar, we assert that

Jesus writes down the law of love, the law that requires opponents to love the woman who seems to be a wrongdoer and unworthy in the community. Jesus establishes a law that does not rush to destroy life, but to sustain it. The law that saves the lost ones like the woman in this text (Mligo 2011:317).

In that light, Jesus would not approve of the use of the barbaric act of violence on the woman (Joseph 2016). Kysar provides a compendium of Johannine literature on the issue (Kysar 1975; Martin 2016). It is our opinion that the association of the theme of the "finger of God" with Luke, the evangelist, is due mainly to his knowledge of the Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible in Urban Hellenistic Christianity (Cadbury 1927:213-253) concerning what God had done on Mount Sinai (Ex 31:18; Deut 9:10). This is a reliable indication that Luke probably had a hand in the composition of this story. The fact that this is like a Lukan theology, which drew the attention of his audience, nowadays draws our attention to recognize the presence of the very rule of God and the choice for non-violence in the lives of men (and women). Jesus' action can be taken as a tactic to delay action in order to "exhibit a concern with the rights of women" (The African Bible 1999:1799).6

2.2.4 Verses 6c-8

In this unit, Jesus' response is rather elusive to the "accusers" and even to the listeners (audience) of his teaching. It is imprecise to the persistent questioners who became more embarrassed by Jesus' silence. Jesus released the challenge when he said to them: Ό αναμάρτητος υμων πρωτος έπ’ αύτην βαλέτω λίθον - Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her. Jesus thus speaks indirectly to the woman and directly to the accusers (religious leaders) in that the law cannot justify both of them. Jesus' statement encapsulates a positive moral. By writing on the ground and by heaving a sigh, Jesus identified with creation that groans for the emancipation and liberation of the woman from patriarchal domination and oppression. In her, all humanity is identified as conditioned to sinfulness; a theme that is again typical of Luke (Lk. 5:20; 7:47-48; 11:4; 24:47). But, for Jesus, humanity has the option to live from "sinfulness to sainthood". For a known sinner such as the sinful woman in Luke 7:36- 50, the death penalty is not the answer. Rather, it is an aberration in the divine economy. In the eyes of God, the life of the woman means much more than her summary execution. As in Luke 21:1-4, Jesus overrides the complacency and worldliness of the Jewish religious leaders represented by the Scribes and the Pharisees who pretended to be the most pious. In short, Jesus recognizes the sinful woman for what she is, the weak human being (Atere 2001:60-62). Though appended to John's Gospel, the story is in line with the central theme of Luke's salvation history where Jesus is the Lord who has come (Puskas & Crump 2008:128-129) to bring God's salvation to humanity. For Luke, Jesus vindicates the outcasts over the self- righteous religious rulers who stood out as representatives of the inhuman degraders of women through culture. Schussler Fiorenza elaborates on this point:

The prescription of the Holiness Code, as well as the scribal regulations controlled women's lives even more than men's lives, and more stringently determined their access to God's presence in Temple and Torah. Jesus and his movement offered an alternative interpretation of Torah that opened up access to God for everyone who was a member of the elect people of Israel, and especially for those who, because of their societal situation, had little chance to experience God's power in Temple and Torah (Schussler Fiorenza 1983b:141).

2.2.5 Verses 9-11

These verses conclude the narrative. The reaction of the accusers, who ask Jesus for his opinion, not out of concern for the woman, but to put Jesus to the test (Beutler 2017:88), is one of withdrawal, one after the other. In the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus is portrayed as one conferred with the authority to heal the sick, open the eyes of the blind, forgive sin, and raise the dead. Jesus condemns the sin and not the sinner, unlike the "scribes and Pharisees" who lack understanding. For whosoever the author is, the thrust of the story is that Jesus is portrayed as "the representative of a God who desires the life of a sinner and not his death" (Beutler 2017:89). In John's Gospel, there are abundant links with the Synoptic Gospels on narratives with such portrayals of Jesus. The following texts from the Synoptic Gospels substantiate our observation:

• Luke 21:37 parallels John 8:1, where Jesus returns to Mount Olives at night. The details about Jesus and his partners are inspired by the Synoptic tradition represented in Luke. Besides, Jesus' attitude towards the woman who is a sinner in Luke 7:36-50 matches Jesus' gentle approach to this other woman in John 8:1-11.

• The group "scribes and Pharisees" refers to Synoptic tradition actors and are not Johannine (Matt 15:1-7, 23:23; Mk 3:6, 5:27-30; Lk 5:17-21, 7:36-50). In John 3-6b, the "scribes and Pharisees are not usually heard of in John's gospel but those who confront Jesus are "the Jews" (v. 5:1, 10, 15, 16, 18) and the "Chief Priests and Pharisees" (v. 7:45).

• The synoptic account of "My son, your sins are forgiven" (Mk 2:5; Matt. 9:2c; Lk. 5:20b) is congruent with John 5:14, where Jesus orders the paralytic, who has received healing, with the expression: "Go sin no more".

• Jesus' teaching on marriage and divorce (Mk 10:2-12 and parallels) is considered a rigorous teaching by the "Scribes and Pharisees" in John, who would say to him: "Moses permitted us to divorce her, what do you say?". In John 8:1-11, "Moses commanded us to stone such a woman; the Romans say to us, do not; what do you say?" According to Beutler,

If he forgave the woman, then he would be contradicting himself; if he condemned her, then he was acting against the gentleness which he otherwise advocated (Beutler 2017:86).

In both texts, their intention is to put Jesus to the test. In this instance, John shares the test motif with the Synoptic tradition.

• Mark 2:1-12, with the mention of "mat", parallels the narrative on the healing of the paralytic in John 5:1-18. The connection between sickness and sin are points of contact with the Synoptic tradition (Schnackenburg 1968). In this instance, Johannine scholars agree that there is a direct literary dependence of John on Markan tradition (Brown 1970; Neirynck 1991).

• Mark 11:1-10, Matthew 21:1-9, and Luke 19:28-40 - the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem is shared by John with the Synoptics (Jn 12:12- 19). The hymn Hosanna is common in all the four Gospels, except Luke who substitutes Hosanna with Blessed in his own account.

• Jesus' healing of the paralytic in Mark 2:1-12, Matthew 9-8, and Luke 5:7-26 is reported in John 5:1-7. For both the Synoptics and John, Jesus is the one who fulfils the promises of the old prophets (Is. 26:19, 29:18, 35:5) (Beutler 2017:89).

• In Mark 2:11, Matthew 9:6 and Luke 5:24, Jesus orders the healed paralytic, as in John 5:8-9: "Stand up, and take your mat and go". The Synoptic narrative tradition in Matthew 11:5, Luke 7:22, and Acts 3:6, 14:10 corresponds to peripatei - walk around in John 5:8 (Beutler 2017:89).

• Mark 2-3 and Luke 10:13-17 parallels John 5:9d-18, where the debate between Jesus and the Jewish authorities on the rightness of healing on the Sabbath day has links with the Synoptic tradition, as Neirynck of the Leuven School (our teacher at our Alma Mater) observed with Jesus' miracles and the Sabbath observance (Neirynck 1991:699-711).

In sum, we agree with Beutler that the historicity of the passage (Jn 7:53- 8:1-11) and others and "the picture of Jesus which it imparts is a good match with that of the Synoptic gospels" (Beutler 2017:89). Despite some difficult narrative circumstances in the text, it is quite possible that John's text matches that of the Synoptic gospels.

Jesus directs the woman to change her moral behaviour. He acknowledges that, although the woman's action is sinful, he forgives her crime when he perceives her intent to repent. This is due mainly to the remorse demonstrated by the woman who could have equally walked away when the accusers dispersed. But she remained before Jesus whom she acknowledged as Lord. Her implicit faith in the mercy of Jesus set her free from the burden of sin and public assault. Now fully liberated, she is not allowed to continue her sinful state (Boring-Craddock 2009:315), but poreu,ou: go - in the imperative in its present tense, "the mood used to express a command, and in the present tense, a prohibition also, … " (Zerwick-Grosvenor 1979: xx). Jesus orders the adulteress to become a woman disciple.

The narrative extenuates Jesus' function as the compassionate one from God for the woman, as Jesus flatly disassociates himself from condemning her in the statement:

- Neither do I …. Jesus does not condemn the woman who has been condemned by no one else. Instead, Jesus launches a counsel: "sin no more" in an imperative form. By this categorical statement, Jesus "relaxes the norms" intensified by contemporary interpreters (Theissen 1978:79-80).

- Neither do I …. Jesus does not condemn the woman who has been condemned by no one else. Instead, Jesus launches a counsel: "sin no more" in an imperative form. By this categorical statement, Jesus "relaxes the norms" intensified by contemporary interpreters (Theissen 1978:79-80).

3. COMPARABLE AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES ON THE TELLTALE NATURE OF THE NARRATIVE

It is well known that, before the advent of literacy in most parts of Africa, various forms of stories were known and had been circulated orally. Literary critics identify two major genres of African stories. There are stories connected with the origin of communities and individual existence - their cosmogonies (Onuekwusi 2013:31-34). Other types of stories created by the sages of Africa abound, such as folktales. These anonymous traditional stories have been transmitted orally. These stories are fairly popular and usually found among every ethnic group. The folktales provide informal education for both adults and children, and offer lessons in morality, endurance, and bravery. In the African cultures, folktales also fulfil entertainment and didactic functions. They are creatively imaginative and can be fantastic such as the story of the woman caught in adultery in the Gospel of John. These involve human beings (the Scribes and the Pharisees and the woman) and a supernatural character (Jesus). This story in John, believed to have been authored by Luke, displays numerous improvisations that afforded the narrator copious use of his creative imagination as he strove to present an apparently veritable three-man theatrical scenario where the roles of men, the accusers, the speechless woman and Jesus are acted out through narrative modulations. In terms of the wisdom and knowledge of his Christian audience for whom the evangelist/s wrote this story, he did increase the complexity of verbal expressions in the text, spiced the narration with idioms, queries and some gnomic patterns of narrative acts for adult members of his church, while he retained the simple declarative statements for the younger audience, in order to ensure that the key moral of the story is not lost. His ultimate purpose is to ensure that there is a story line, as there are in many Nigerian oral stories, and lessons to be derived from the narrative.

Luke is decidedly pro-woman (Lk. 7:36-50, 8:1-3, 10:38-42, 13:11-17, 23:55-24:1-11; Acts 6:1-6) (Puskas & Crump 2008:133). There is consensus of opinion among scholars that Luke shows concern for women and the marginalized who, for Jesus, "stood on the same level as men" (The African Bible 1979:1743) and the footnotes; (Danker 1976:89-106; Maddox 1982; Marshall 1992:30- 42; Gaventa 2003). Luke is most woman-friendly in the events narrated in his Gospel and in The Acts. He accords women their rights in the Christian community. He recognizes women as equal partners in the economy of salvation. Our exegesis directs us to put this cardinal finding at the disposal of contemporary social analysts in Nigeria. Despite the non-agreement among scholars on the place of composition (Puskas & Crump 2008:150; Marshall 1980:45), the major themes and concerns are issues such as salvation to the Gentiles, the progress of the gospel, the Holy Spirit, prayer, wealth, poverty, women, and the oppressed (Arlandson 1997). Some Lukan scholars agree that the themes covered in the two- volume work (Luke-Acts) provide clues to the circumstances of Luke and his readers (Cadbury 1927:308-316; Easton 1955:41-57). Luke's community appears to include Gentile believers, those from the phoboumenoi "God- fearers" (Kiddle 1935:160-173) who attended the synagogue to seek the face of God in the newer appeal of the gospel preached by Paul and Luke, in order to escape "Jewish and pagan antagonism" (Puskas & Crump 2008:152; Nolland 1989:xxxii-xxxiii). Luke confirms the continuity that exists between the life of the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth and the life and ministry of the Christian churches now spread throughout the Roman Empire (Puskas & Crump 2008:151).

We observe, in this instance, that Luke's concept of salvation history is closely tied to the idea of the fulfilment of Scripture. This feature aligns Luke-Acts with Israelite/Jewish historiography, and allows us to accept the narrative of the adulteress woman as a text consciously inserted into John's Gospel to match Jesus' declaration of bonus shalom in John 10:10. According to Okure, in the spirit of John 10:10, it is, inter alia, a

summative and programmatic passage [where] Jesus declares that the sole purpose of his coming into the world is so that human beings may have life and have it to the fullest … and [that] concerns for … personal, human welfare … characterizes Jesus' entire ministry (Okure 1992:89).

3.1 The pastoral implications of the narrative

The story of the nameless adulteress represents a case of Jesus' benevolent and honourable attitude towards women's rights. As word of God, the text reminds us of the significance of women's human rights. While Jesus did not condone the action of the anonymous woman, he showed her compassion and liberation. Jesus realized that stoning her to death would have meant doing violence to her right to life and the desecration of the image of God she bore in her. His directive: "Go, sin no more." is a command to the woman (as well as to men) and the many others like her in our nations to embrace re-integration and empowerment. By her empowerment, she and her likes are challenged to realise their full potential to "humanize politics and work by virtue of their feminine qualities" in the human community (Schussler Fiorenza 1983b:56 n. 5). Indeed, this re-incorporation indicates that women "are human persons, who demand free development of full personhood" (Schussler Fiorenza 1983b:a57). As "responsible subjects of their own lives" (Schussler Fiorenza 1983b:58), they have the ability to save their nations and people from destruction as long as they are allowed to contribute to the promotion of life in their communities (Uchem 2001:29). Literarily speaking, the story reflects a cultural obstruction, eclipse and inhibition of the freedom, initiative and creativity of women. From a pastoral perspective, it is not the will of God that the life of any person, created in his own image and likeness, should be "wasted", because she is a woman.

In the social Sitz im Leben of the Johannine communities, the interpolated story draws attention to the following lessons worth giving pastoral orientation:

• Human beings are all sinners.

• God reveals himself to sinners.

• God saves sinners.

• God can make a sinner become a saint.

• Humanity can move from sinhood to sainthood.

• God operates his judgement through Jesus.

Therefore, the morals derived from re‑reading this story call on us all and the Church to begin to socially de-construct decadent taboos placed on the womenfolk as Haram (evil) by militant Islamists. Heeding this call shall pave the way to re-enact gender equity that bespeaks our inclusive oneness in the family of God, the Church. In Jesus' demonstration of compassion and mercy to the sinful woman, the transforming power of God and its potential significance for Christian life are concretized (Martin 2016:600-602). Thus, Jesus' attitude encourages us to appreciate the need for the erection and formation of inclusive familial communities, where all forms of unjust and inhumane repression to persons based on gender must be eliminated (Uchem 2001:172-174). Jesus' action in liberating the woman has overridden the decadent dictates of religion, fanaticism and the obnoxious cultures in favour of a zero tolerance to gender disparity. The evangelist(s) have provided us a Jesus who operationalizes the transformation of all human imperfections and sour relations, and who directs us to reckon with his call for "equal rights within the churches" (Schussler Fiorenza 1983a:63), especially in our own context (Nigeria), as the former administration in Nigeria made Transformation a pivotal policy agenda in its governance.

4. CONCLUSION

The set objective of this article is clear from the outset. Our task is to provide a tool for interpreting and understanding Jesus' attitude towards women in an overtly patriarchal society, as those of the Jews of the Second Temple period, and its relevance in our search for ideas that can help raise the profile of demeaned women in Nigeria. Through an objective study of John 7:53-8:1-11, we ventured into the scholarly discourse on the historicity of the passage's manuscript tradition. We noted, in agreement with many Johannine scholars, that the text is most probably a fourth-century interpolation of a Luke-like narrative, which we do not know exactly when it was written, since it is opined that he might have written his two-volume work after 70 and before 140 AD (Puskas & Crump 2008:152). The aim is to help us establish the authenticity of the text and to avail ourselves of the pertinence of the Christology it transmits, in order to promote women's liberation theology in the Nigerian context. In order to achieve this objective and in light of our context of interpretation, we surveyed the socio-cultural roles fulfilled by both "ancient and modern" Nigerian womenfolk whose bravery, heroism and activism inspire our re‑reading of Jesus' gentleness towards the accused woman's rights and her associated rescue, especially from a patriarchal society such as Nigeria, where the rights of women are being degraded by waves of terrorism and Islamic insurgency. Due to the militancy of the Boko Haram terrorists in north-eastern Nigeria, all of the 276

Chibok girls abducted by the Islamists three years ago have still not been released. In addition, over 1,000 women and girls have been kidnapped and taken to unknown places. These Nigerian womenfolk are abused, raped and denied their fundamental human rights.

In order to observe how our exegesis of John 7:53-8:1-11 impacts on this dastardly state of affairs in Nigeria, we pursued the interpretation of the text first, by exploring the structural analysis of the content. The exposition helped us gain insight into the dialogue between Jesus and the "Scribes and Pharisees", the custodians of the Mosaic Law at that time. Our exegetical analysis revealed the meaning of Jesus' writing on sand, his silence on the case brought before him, and the silence of the accused woman. Both the Synoptic and Lukan scholarship on the interpretations of the text were concisely discussed. The findings were used to process a Christology of Jesus whose "finger" is invested with divine powers to save life and not to waste it. Other findings were put at the disposal of a pro- life theology for those Nigerian women who are hoping for liberation from androcentric domination, exploitation and terrorist ruination of their lives in a post-colonial era in Nigeria.

The paper concludes that Jesus' attitude towards the adulteress woman supports the fact that any religious and cultural traditions that perpetuate the violation of women's human rights are reprehensible. Schussler Fiorenza asserts that "… Jesus and his movement were open to all; especially the outcasts of his religion and society" (Schussler Fiorenza 1983a:141). In dissonance with the Jewish laws, "the nameless adulteress who was not judged but saved by Jesus … belongs to Jesus' very own disciples" (Schussler Fiorenza 1983a:333). Schussler Fiorenza also amplifies that the woman is represented not simply as a paradigm "of faithful discipleship to be imitated by women but by all those who belong to Jesus' "very own" familial community" (Schussler Fiorenza 1983a:333) and any person who can counsel the Jihadists in Nigeria. We also agree with Russel that, in

respect of the fundamental rights of the person, every type of discrimination, whether social or cultural, whether based on sex, race, color, social conditions, languages or religion is inhuman (Russel 2000:64).

In this story, Jesus prominently stands out and affirms that any unjust patriarchal structures and mistreatment of the struggles of the womenfolk in rural nooks and crannies of Nigeria as Haram - evil - are "to be overcome and eradicated as contrary to God's intent" (Russel 2000:64). This is our view on the Nigerian women: our mothers, daughters, sisters and wives who continue to experience male-instigated terrorism, domination and oppression.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akintunde, D.O. (ed.). 2001. African culture and the quest for women's rights. Ibadan: Sefer Books. [ Links ]

Anderson, P.N., Just, F. & Thatcher, T. 2016. John, Jesus and history. Glimpses of Jesus through the Johannine lens. Vol. 3. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press. [ Links ]

Arlandson, J.M. 1997. Women, class, and society in Early Christianity: Models from Luke‑Acts. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson. [ Links ]

Atere, M. 2001. Women against women: An obstacle to the quest for women's rights in Yorubaland. In: D.O. Akintunde (ed.), African culture and the quest for women's rights (Ibadan: Sefer Books), pp. 58-75. [ Links ]

Bateye, B.O. 2010. Rethinking women, nature and ritual purity in Yoruba religious traditions. In: C.U. Manus (ed.), Biblical studies and environmental issues in Africa. NABIS West Biblical Studies 1 (Lagos: Alofe Books), pp. 276-295. [ Links ]

Becker, U. 1963. Jesus und die Ehebrecherin. BZNW 28. Berlin: Topelmann. [ Links ]

Beutler, J. 2017. A commentary on the Gospel of John. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Boring, M.E. & Craddock, F.B. 2009. The people's New Testament commentary. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Brown, R.E. 1970. The Gospel according to John. Vol. 1. Anchor Bible 29. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Bultmann, R. 1971. The Gospel of John. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press. [ Links ]

Cadbury, H.J. 1927. The making of Luke‑Acts. New York: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Claassens, J. 2016. Claiming her dignity: Female resistance in Old Testament. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. [ Links ]

Danker, F.W. 1976. Luke. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Derrett, J. D. M. 1995. Circumcision and Perfection: A Johannine Equation (John 7:22-23), Studies in the New Testament, vol. 6, Leiden, pp. 97-110. [ Links ]

Easton, B.S. 1955. Early Christianity: The purpose of Acts, and other papers. London: SPCK. [ Links ]

Fabella, V. & Oduyoye, M.A. (eds) 1988. With passion and compassion - Third‑world women doing theology: Reflections from Women's Commission of Ecumenical Association of Third‑ World Theologians. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Fani-kayode, F. 2013. The Punch. Friday, July 26, 17(20):9. [ Links ]

Fee, G.D. 2002. New Testament exegesis: A handbook for students and pastors. 3rd ed. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Funk, R.W. 1990. New gospel parallels. Vols 1 & 2 Mark. Rev. ed. Sonoma, CA: Polebridge. [ Links ]

Gaventa, B.R. 2003. Acts. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Gundry, R.H. 1982. Matthew: A commentary on his literary and theological art. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Harris, X.J. 1991. Ministering women in the Gospels. The Bible Today, March:100-112. [ Links ]

Humble, S.E. 2016. A divine round trip. The literary and christological function of the descent/ ascent Leitmotif in the Gospel of John. (Contributions to Biblical Exegesis & Theology). Leuven: Peeters. [ Links ]

Joseph, S. 2016. The Nonviolent Messiah. Jesus, Q, and the Enochic Tradition. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. [ Links ]

Kiddle, M. 1935. The admission of the Gentiles in St. Luke's Gospel and Acts. Journal of Theological Studies 36 (2):160-173. [ Links ]

Komoszewiski, J. (ed.), Sawyer, M.J. & Wallace, D.B. 2006. Reinventing Jesus: What the Da Vinci Code and other novel speculations don't tell you. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications. [ Links ]

Kreitzer, l.J. & Rooke, D.W. (eds) 2000. Ciphers in the sand. Interpretations of the woman taken in adultery (John 7:53‑8:11). The Biblical Seminar, 74. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Kysar, R. 1975. The fourth evangelist and his Gospel: An examination of contemporary scholarship. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg. [ Links ]

Lasebikan, E. 2001. African culture and the quest for women's rights: A general overview. In: D.O. Akintunde (ed.), African culture and the quest for women's rights (Ibadan: Sefer Books), pp. 11-23. [ Links ]

Laymon, C.M. (ed.) 1971. The interpreter's one‑volume commentary on the Bible. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Lemarquand, G. 2004. An issue of relevance: A comparative study of the bleeding woman (Mk 5:25‑34; Mt 9:20‑22; Lk 8:43‑48) in North Atlantic and African contexts. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Maddox, R. 1982. The purpose of Luke‑Acts. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Reprecht. [ Links ]

Manus, C.U. 1984. The subordination of women in the Church: 1 Cor 14, 33b-36 reconsidered. Revue Africaine de Théologie 8 (2):183-195. [ Links ]

Manus, C.U. 1999. Towards the promotion of African women's rights: A re-reading of the priestly-Jahwist creation myths in Genesis. Neue Zeitschrft für Missionswissenschaft 55 (1):58-62. [ Links ]

Manus, C.U. 2002. Gender bias against women in some sacred narratives: Re-reading the texts in our times. In: A. Ojo (ed.), Women and gender equality for a better society in Nigeria (Leaven Club International, Lagos), pp. 63-83. [ Links ]

Manus, C.U. 2003. Intercultural hermeneutics: Methods and approaches for New Testament studies in Africa. Nairobi: Acton Publishers. [ Links ]

Manus, C.U. 2007. The death of Jesus (Jn 19, 28-30): Contextual hermeneutics of life and death in the HIV/AIDS era in Africa. In: G. van Belle (ed.), The death of Jesus in the Fourth Gospel (BETEL CC: Leuven University Press), pp. 859-872. [ Links ]

Manus, C.U. 2010a. Biblical foundations for ecofeminism and its challenges in the Nigerian context. Ife Journal of Religions 6(1):1-19. [ Links ]

Manus, C.U. 2010b. A bizarre exodus typology in Lk 11:20: Reflections on Lukan inculturation hermeneutics in the Nigerian context. In: D.O. Ogungbile & E.A. Akintunde (eds.), Creativity and change in Nigerian Christianity (Lagos: Malthouse Press), pp. 19-36. [ Links ]

Manus, C.U. (ed.) 2010. Biblical studies and environmental issues in Africa. NABIS West Biblical Studies 1. Lagos: Alofe Books. [ Links ]

Marshall, I.H. 1980. The Book of Acts: An introduction and commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Marshall, I.H. 1992. The Acts of the Apostles. Sheffield. Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Martin, G. 2016. Bringing the Gospel of John to life: Insight and inspiration. Huntington: Sunday Visitor Publishing Division. [ Links ]

Menzies, R.P. 1994. Empowered for witness: The Spirit in Luke‑Acts. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Mligo, E.S. 2011. Jesus and the stigmatized: Reading the Gospel of John in a context of HIV/ AIDS‑related stigmatization in Tanzania. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications. [ Links ]

Mundele, A.N. 2012. A handbook on African approaches to Biblical interpretation. Limuru, Kenya: Kolbe Press. [ Links ]

Neirynck, F. 1991. John 5:1-18 and the Gospel of Mark. A response to Peder Borgen. In: F. van segbroeck (ed.), Evangelica II (BEThL 99, Leuven), pp. 699-711. [ Links ]

Nolland, J. 1989. Luke 1‑9:20. WBC 35. Dallas, TX: Word Books. [ Links ]

Oduyoye, M.A. 1995. Daughters of Anowa: African women and patriarchy. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Oduyoye, M.A. 2001. Culture and the quest for women's rights: Keynote address. In: D.O. Akintunde, African culture and the quest for women's rights (Ibadan: Sefer Books), pp.1-10. [ Links ]

Ogungbile, D.O. & Akintunde, E.A. (eds) 2010. Creativity and change in Nigerian Christianity. Lagos: Malthouse Press. [ Links ]

OJO, A. (ed.) 2002. Women and gender equality for a better society in Nigeria. Leaven Club International. Lagos. [ Links ]

Okure, T. 1988. Women in the Bible. In: V. Fabella & M.A. Oduyoye (eds), With passion and compassion - Third‑world women doing theology: Reflections from Women's Commission of Ecumenical Association of Third‑World Theologians (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books), pp. 75-89. [ Links ]

Okure, T. 1992. A New Testament perspective on evangelization and human promotion. In: J. Ukpong et al. (eds), Evangelization in Africa in the third millennium: Challenges and prospects. Proceedings of the First Theology Week of the Catholic Institute of West Africa. 6-11 May 1990 (Port Harcourt, Nigeria: CIWA Press), pp. 84-94. [ Links ]

O'loughlin, T.A. 2000. Woman's Plight And The Western Fathers. In: L.J. Kreitzer & D.W. Rooke (eds), Ciphers in the sand. Interpretations of the woman taken in adultery (John 7:53‑8:11). The Biblical Seminar, 74 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press), pp. 83-104. [ Links ]

Onuekwusi, J.A. 2013. A nation and her stories: Milestone in the growth of Nigerian fiction and their implications for national development. Inaugural Lecture. Imo State University, Owerri. [ Links ]

Perkins, L. 2004. Why the finger of God in Luke 11:20. The Expository Times, 115 (8): 161. [ Links ]

Pope Benedict XVI 2011. Post‑synodal apostolic exhortation: Africa's commitment. Africae Munus, Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa. Also of great importance to this exhortation is John Paul II, 1988. Mulieris dignitatem - The dignity and vocation of women. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa. [ Links ]

Puskas, C.B. & Crump, D. 2008. An introduction to the Gospels and Acts. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Russel, L.M. 2000. Mary and Martha: A dream of partnership among women. New Haven, CT: Yale Divinity School. [ Links ]

Schnackenburg, R. 1968. The Gospel according to St. John. New York: Herder & Herder. [ Links ]

Schussler Fiorenza, E.S. 1983a. Discipleship of equals: A critical feminist ecclesiology of liberation. New York: Crossroad. [ Links ]

Schussler Fiorenza, E.S. 1983b. In memory of her: Feminist theological reconstruction of Christian origins. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Shepherd, M.H. 1971. The Gospel according to John. In: C.M. Laymon (ed.), The interpreter's one‑ volume commentary on the Bible (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press), pp. 707-728. [ Links ]

Stein, R.H. 2001. Studying the Synoptic Gospels: Origin and interpretation. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. [ Links ]

Talbert, C.H. 1984. Reading Luke. A literary and theological commentary on the Third Gospel. New York: Crossroad. [ Links ]

Theissen, G. 1978. The first followers of Jesus: A sociological analysis of the earliest Christianity. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Uchem, R.N. 2001. Overcoming women's subordination: An Igbo African and Christian perspective envisioning an inclusive theology with reference to women. Enugu: Snaap Press. [ Links ]

Ukpong, J. et al. (eds) 1992. Evangelization in Africa in the third millennium: Challenges and prospects. Proceedings of the First Theology Week of the Catholic Institute of West Africa. 6‑11 May 1990. Port Harcourt, Nigeria: CIWA Press. [ Links ]

Van Belle G. (ed.) 2007. The death of Jesus in the Fourth Gospel. BETEL CC. Leuven: Leuven University Press. [ Links ]

Van Segbroeck, F. (ed.) 1991. Evangelica II. BEThL 99. Leuven: Leuven University Press. [ Links ]

Wendel, S.J. & Miller, D.M. 2016. Torah ethics and early Christian identity. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Williams, D.T. 2003. Why the finger of God, The Expository Times 115 (2): 46. [ Links ]

Zerwick, M. &. Grosvenor, M. 1979. A grammatical analysis of the Greek New Testament. Vol. I: Gospels - Acts. Rome: Biblical Institute Press. [ Links ]

Zinkuratire, V. & Colacrai, A. 1979. The African Bible. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa. [ Links ]

1 Prior to this, the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights had attracted much attention and support. As a global women's movement, the Conference produced the Vienna Declaration and Program of Action. If being borne by a woman confers on every person fundamental human rights, women who are also born into this world and whose rights are violated time and time again by battering, rape, sexual slavery, etc. are naturally entitled to fundamental human rights in all its ramifications. Surely, human rights of women are no longer restricted to education. Some female scholars attest that the Declaration insists that civil, political and religious rights belong to women as much as to men (Atere 2001:62).

2 Boko Haram briefly means 'disapproval and hatred of western education as evil' by the Islamist militants in north-eastern Nigeria. Between May 5 and 7, 2017, it was reported that the militants have released 82 of the girls they have held captive since 2014 in exchange of some of their violent men held by the Nigerian Military Authorities. What happens to the rest of the girls: traumatized and brow-beaten? This explains how the group are seen as people who have neither conscience nor morality.

3 Some of the women activist groups include Women Arise for Change Initiative, Women Empowerment, and Legal Aid. Recently, members held a summit on child marriage in Lagos, Nigeria.

4 The expressions in italics are mainly Pidgin English and Igbo, the languages generally spoken by the people who live in south-eastern Nigeria and who may constitute the majority of the readers of our article. The English translations have been provided.

5 The "Teacher" had occupied an established order in the Apostolic Church (1 Cor 12:28; Eph 4:11). As Luke states in Acts 21:28, Jesus was described as "the man who teaches all men everywhere against our people and our law and this place …". When the term is addressed to Jesus, it refers to him as the bearer of true wisdom in the depths of God, taught to men not by means of "human wisdom but taught by the Spirit" and as one who is bold and fearless of the establishment and its institutions. See 1 Cor 2:2. He is the teacher come from God (Jn 3:2), the man who taught correctly "the way of God" (Matt 22:16; Mk 12:14; Lk 20:21).

6 See commentary on 8: verse 4f.