Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.37 n.1 Bloemfontein 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v37i1.1

ARTICLE HEADING

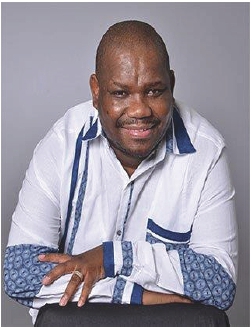

Interview With Rothney S. Tshaka

Martin Laubscher

ML: Please introduce yourself.

I started my theological training at the Faculty of Religion and Theology at the University of the Western Cape in 1997. After completing my BTh, I moved to the University of Stellenbosch to further my theological studies. The move to Stellenbosch happened as a result of a move of the URCSA to a different centre for the training of her candidates for the ministry. I completed an MDiv - cum Laude - as well as a Licentiate in Theology. I spent a brief period at the Vrije Universiteit van Amsterdam where I completed a Masters in Theology. I returned to the university where I completed my Doctorate in Theology. I have taught briefly at the Murray Theological College in Morgenster, Zimbabwe. My move from Zimbabwe was necessitated by a call to the New Brunswick Theological Seminary in New Jersey, where I occupied the position of Associate Professor of Community and Ethics as well as the Global Scholar on Ethics at the mentioned institution. Currently, I am the Acting Director of the School of Humanities at UNISA.

ML: How would you describe "your theology"?

RST: I describe my theology as thoroughly contextual. I have always believed that any theology that is not in touch with its contexts is boring and not worth pursuing. It is for this very reason that my theology intersects with issues of race, politics, culture, and the economy. I believe that any reflection or rather "thinking after God" needs to happen in conjunction with the socio‑economic and cultural aspects of the individual Christian. So, for me, theology has always been public, and this was evidenced in Black Theology of Liberation as well as African Theology.

ML: What is the meaning and role of "Black lived experience" in doing theology today?

RST: First and foremost, I believe we are being disingenuous if we want to create the impression that the situation that we find ourselves in (the situation of having the majority of Black people across the globe struggling more than White people, for instance) as ordained by God. I believe that this situation is a manmade situation which had the support and backing of colonialism and apartheid in our situation. The notion, 'Black lived experience' refers to the living experiences of the majority of Black people, which rarely becomes part of the main conversations that are held in society today. It refers to that group of people in whose paths unimaginable obstacles are deliberately thrown and yet it is expected of them to survive despite the obstacles. It is this narrative, which had been deliberately kept marginal, which must now in my view be made central forcefully. I believe that such calls for the Africanization of the academic curricula are calls that realize the urgency of bringing these narratives to the centre. The Black lived experiences should inform public discourses nowadays.

ML: Please name and reflect a little on the most significant voices in your theological formation thus far.

RST: Since my latest interest in theology intersects with issues of epistemologies of the South, I have started to read myself into the methodologies propagated by the likes of Enrique Dussel, Bonaventura De Sousa Santos and others in that trajectory towards attaining a decolonial context, in which the alternative epistemologies are brought to the core of public discourse. While their approaches seem fresh and innovating, I remain of the view that the calls mounted today for Africanizing mainstream knowledge production in South Africa have been made abundantly clear by proponents of Black theology, although their calls themselves were located in Eurocentrism. I believe that any attempt at taking Africanity seriously must engage with Africa and her worldviews and that the Christian faith, as appropriated by us, must concede that an overhaul is necessary so that being African and Christian is no longer perceived to be absurd. The work of Kofi Asare Opoku comes to mind in dealing with this matter, but there are also a number of other African scholars who could be cited in this instance. I am thinking of young South African scholars such as Vuyani Vellem, Ndikho Mtshiselwa, Boitumelo Senokoane, and Tshepo Lephakga, who are making headway in theological circles with which I am affiliated.

ML: How would you speak theologically within the current discourse on "decolonization" on our South African campuses?

RST: Most of this has already been said, albeit cursorily, in the previous questions. I do think, however, that this is a long overdue project. For a very long time, theological education in this country has been content with a Eurocentric theology. Africans were encouraged to mimic this form of theology to such an extent that they are, in some circles, more Eurocentric in their reflections of theology than some Europeans themselves. Calls for #RhodesMustFall and other fallist movements are calls that have originated and taken ground and cannot be linked to particular theories. This fact speaks to the reality that Eurocentric theories are increasingly becoming irrelevant and, therefore, the verdict of Bonaventura that there exists a phantasmal relationship between theory and practice. I remain of the view that African and Black theologies have already spoken about the issue of decolonization since the late sixties and early seventies. Yet it seems unavoidable that this reality - of a decolonized theology at present - is inevitable. To some extent, the negotiated settlement that we currently know of as the new South Africa has unfortunately not allowed for a conversation in which South Africans, both Black and White, could speak about our historical baggage and carve a path where we all feel we belong to this country. Black and African theologies have tried this, but have been muted by claims that it was militant and, therefore, not proper theology. What is currently happening on university campuses is something that should have happened a long time ago. In this country, we have observed something contrary to what happened in other African countries with the independence of African countries from their colonial masters. Instead of South Africa following the example of Africanization, in this country in the 1960s, apartheid policies were hardened. This is the reality of the situation and we must accept that so that in going forward we are sincere in leading this country to one in which all who belong in it feel that they indeed are part thereof and not second‑ or third‑class citizens.

ML: What is your take on the "developments" and "transformation" of systematic theology in South Africa after 1994?

RST: Systematic Theology has, in my opinion, not transformed much since 1994. This is evidenced by what is still being taught in university curricula. Most of the actors are White and European. I sometimes get a sense that our adherence to European theology and attempts at imbibing a kind of European spirituality is so out of sync with what is happening in Europe nowadays. Let me give you this example. On more than one occasion during my visits to Geneva, I was flabbergasted by the fact that a so‑called "reformed spirituality", which we are encouraged to adopt, is non‑existent in Geneva. Why should that still be important? Why does that not become merely some part of historical theology? We in Africa have a unique opportunity of presenting our diversity to the world. Why should Black and African theologies still be classified as third‑world theologies in African universities? Why are Black lived experiences not made core since that is the reality of many of those who train for the ministry. Why can't we have interlocutors with whom we can identify? To say this is by no means to suggest that we ought to throw away what is Eurocentric, on the contrary, it would be hypocritical of me to suggest that, because, whether we like it or not, we are all part of Eurocentrism, since we went to the schools, the universities, and the churches that advocated that Eurocentrism. But to call for the marginal to become core lies precisely in admitting that one is not able to learn from marginal narratives when the Western Eurocentric epistemologies and worldviews remain intact and unquestioned. We need political will to bring about the necessary change in the curricula of universities.

ML: Against the above background, how do you envision "being a theologian" and "doing theology" within the next decade in this context?

RST: Because we are drenched in Eurocentrism, we have developed a belief that what is African is barbaric and backward and, therefore, in need of salvation from the West. This mental picture needs to be remedied. Once this is done, we can engage with African worldviews and belief systems not in a romanticized manner, but in a genuine manner that also allows for critique of the held views. I have learned from African proverbs that truth or knowledge is derived in the community only. This means that no one must ever have the last word and claim that she alone is right. There is an African proverb that says, the wise man does not say he knows, but the fool insists. Western epistemologies have this recalcitrant attitude of thinking that it has the last word in what is knowledge. We need to learn other African lived experiences and I am sure we will come back from those experiences as changed people. So I dream of a context of doing theology in which I do not have to dismiss that my great grandparents are being barbaric and backward simply because the arrival of western Christianity in Africa created that impression and that became a condition of my inclusion into the Christian faith. I believe that there has been divine intervention in Africa way before the arrival of western Christianity. Knowing this empowers me not to point out that my brother or sister, who believes differently than me, are backward and therefore barbaric.

ML: You represent a new, emerging and younger generation's reading of Karl Barth's theology in South Africa nowadays. How does "your Barth" differ from other generations' reading of him in South Africa? How significant is this question in light of all the previous questions?

RST: One of the things that galvanized me to consider my context in my theological reflections of God was my reading of some of Barth's views about his own theology. I stumbled on a letter he had written to one of his students in Asia who had asked that he gives his permission to teach his theology somewhere in Asia. The response was, in my opinion, fascinating. He reminded the student that his was a theology that had a particular context, namely Germany. It was very important that the requester noted that very important aspect. Secondly, I have always been more interested in the younger Barth. The Barth who was involved in the establishment of a union while in Safenwil, who joined a political party and who did, in fact, became a theologian in touch with the bread‑and‑butter issues of people. It is my view that the Barth that I think about when engaging some of the issues I am engaging nowadays is the very Barth who, albeit being very critical of natural theology and, to a great extent, opposed to an anthropocentric view of God, would understand the context that we relate God to the satiation in which we think of that God. For him and for me, our reflections of God can never be perfect, because, when that happens, God ceases to be God. The idea of God, therefore, always eludes us.

ML: Lastly, what do you expect from the Reformation 500 celebrations this year?

RST: I am part of an international group that is working on an exhibition called "Living (the) Reformation Worldwide". The brief is that we work on a banner that will showcase the reformation experience across the globe. I have learned with dismay that we are way behind many communities who have intentionally made the reformed tradition their own in their various contexts. They have, as it were, domesticated the reformed ideals and asked this reformation to speak to their socio‑cultural contexts. I am encouraged though by the Northern Theological Seminary of the URCSA, which has adopted the adage, African reformed Praxis. I am hoping that, during this celebration, we will work towards crystallising that ideal.