Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.36 suppl.24 Bloemfontein 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v36i1.8s

ARTICLE HEADING

The Black Church as a caring community for the poor: Southern Synod as investigative centre1

Prof. L. Modise

Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology; Associate Professor in Systematic Theology at the University of South Africa, and Minister of Religion in URCSA modislj@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

In this article, the researcher discusses first the Black Church in relation to God, one another, and the world and, secondly, the blackness of the URCSA reflected in terms of her membership's pigmentation and her identity of the Black church. Thirdly, the author illustrates why a Black theology of liberation is needed in the post-apartheid era in terms of the poverty level in South Africa. On average, 4.35% of Whites are poor in comparison to 61.4% of poor Black African people. Finally, the author focuses on how the Black church should be a caring community for the poor, destitute, oppressed and wronged in both church and society.

Keywords: Black Church, Poverty, Caring Community, Belhar, Confession

Trefwoorde: Swart Kerk, Armmoede, Omgee Gemeenskap, Belhar Belydenis

1. INTRODUCTION

This article focuses on the Black church. This is cause for concern for members of the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA) and the people of South Africa who are enjoying the benefits of the arrival syndrome, and live in a multicultural church and society, but have not yet arrived. I will define what is meant by and what constitutes a Black church as a caring community, with reference to the URCSA as the church of Belhar Confession.

It is true that Black is beautiful, but at the same time blackness is equivalent to poverty. The researcher is not apologetic when he equates blackness to poverty, because poverty is an act of love and liberation. It has a redemptive value (Gutierrez 1988:172). Gutierrez also argues that it is rather because of the love for, and solidarity with others who suffer in poverty. It is to redeem them from their sin and to enrich them with his poverty. It is to struggle against human selfishness and everything that divides people and allows that there be rich and poor, possessors and dispossessed, oppressors and oppressed. The church of Belhar Confession needs to stand where God stands with the poor and wronged. This act of confessing that Jesus is the Lord will be observed in the Black church as a caring community for the poor. This article highlights how these men and women who, proclaiming that Jesus is the Lord, will receive long-service awards, having volunteered to be poor for the sake of their congregations. I will highlight how the Black church as a caring community needs to respect and care for its senior citizens in the service of the Lord. The following section points out what is meant to be a Black church.

2. THE BLACK CHURCH IN RELATION TO GOD, ONE ANOTHER, AND THE WORLD

The Black church is not a singular monolithic institution. It is a vast grouping of local churches that reflects the complex richness of the Black community. Black churches are often as different from one another as the Black community is diverse. These churches vary in terms of size, denominational identities, worshipping ethos, and numerous other factors. While Black churches are typically identified by their membership, the blackness of these churches goes beyond the racial nature of its members. It is a matter of history and socio-political commitment that determines the collective identity of these churches as Black (Douglas 2012:63-64). There will always be those who are apostolic, evangelical, and dogmatic in their liturgy during the church service and the ministry in church and society.

In the Reformed tradition, a church refers to a local congregation, where the Word of God is proclaimed, the sacraments are administrated, and discipline is exercised. These local congregations in the Southern Synod qualify to be a Black church, according to the definition of a Black church, in terms of their history and social-economic-political commitment. Hence, I identified them as a Black church known as the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA). This regional synod consists of 14 presbyteries and 123 congregations. There are two predominantly Indian congregations; 17 predominantly Coloured congregations, and 104 predominantly Black congregations (Batswana, Basotho, aMa-Zulu, aMa-Xhosa). In terms of the political definition of these groups in South Africa, they are generally known as Blacks and they also identify themselves as Blacks. In that spirit, the church in this region is a Black church in terms of membership. Hopkins (1999:43) indicates that

[t]he black church exists wherever [B]lack Christians come together in their own space and time to worship and live out God's all for freedom for the least in the society. In this sense, the [B]lack church is the historical [B]lack churches (e.g., Baptist, African Methodist Episcopal, African Methodist Episcopal Zion, and Christian Methodist Episcopal), newer [B]lack churches (e.g., Pentecostal, Holiness, and nondenominational) and [B]lack church congregations in the White denominations.

One can deduce from the above argument that the URCSA Southern Synod is a Black church in terms of her predominantly Black membership. Futhermore, based on Hopkins' (1999) definition of a Black church, this Synod falls under the last category of Black churches, namely Black church congregations in the White denominations.

Secondly, the Black church emerged as a fundamental part of Black people's resistance to White racist oppression. This point illustrates that being a Black church does not mean that one is racist, but that one is resisting White racist oppression. This does not mean that this church is exclusive, but that it is inclusive in terms of the experience of resistance to White racist oppression, suffering, and poverty. The notion of the Black church, therefore, means a Black church for Black people. This notion of the Black church should not be misunderstood as some sectarian racial theology that envisages Black supremacy and advocates Black exclusiveness. It should rather be understood within its context, namely that, even within the assumed universality of the "church", Black people were dehumanised politically, economically, socially, and theologically. It is important to note that the notion of the Black church did not emerge from White hatred and Black reactionaries to White supremacy (Mdingi 2014:23). An illustration of this example will show why the URCSA Southern Synod needs to be identified as a Black church. In addition, these ministers of the Word and Sacraments have served this church for over 30 years as Black ministers within the Black church, namely the former Dutch Reformed Church in Africa (DRCA) and the Dutch Reformed Mission Church (DRMC). They were dehumanised politically, economically, socially, and theologically due to their blackness within the White-dominated church. This was informed by Article 4 of the Church Order of 1932 of the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC), stating that White ministers should take a lead and influential positions within the Black sector of the so-called DRC family. Even at present, the imprints of that article still exist in the minds of Black brothers and sisters who are members of those church councils that dehumanised these ministers of the Word and Sacraments. The Black church is a classless society, "no class of the have", and "the have not", nor class of the employers or employees. It is a model of the church of the first century, where Christians were regarded as equal brothers and sisters in terms of economic issues; hence, the rich sold their properties and shared among themselves (Act 2:42-45).

At the same time, the Black church has had the most influence on Black values. As evidenced by the way in which many Black people regarded their profession, the Black church plays an inordinate role in shaping Black people's notions of what is morally acceptable or unacceptable. The Black church's importance of Black life is undeniable, if not insurmountable. This church's distinct involvement in the struggle for Black life and freedom determines its blackness. Essentially, the blackness of the Black church is inextricably linked to its commitment to the overall welfare of Black people's body and soul. Simply put, it is the Black church's active commitment to the social, political, emotional, and spiritual needs of Black men and women that makes it Black (Douglas 2012:64). It is evident that, in the former DRCA, this section of the URCSA was very involved with the struggle of the Black people of South Africa. This Synod hosted the well-known Beyers Naude following his excommunication by the DRC for advancing the political struggle for the Black people in the White church. This is the Synod where the well-known politician Carl Niehaus was married in its Black congregation during the apartheid era. The legacy of ministers such as Rev. Dr Samson Tema; Sam Buti, Ezekiel Tema, Lekula Ntoane, Beyers Naude, Gerrie Lubbe and Zac Mokgoebo have served it with dignity and pride.

Lindgren (1965:53) defines a Black church as a fellowship of redemptive love. Unless this redemptive love is realised, the church does not exist in any real sense. Christianity is not primarily an idea, a creed, a form of worship, or an ecclesiastical institution. Christianity is basically concerned with relationships - God's relationship to human beings, human beings' relationship to God, and human beings' relationship to human beings. The life of the Black church is the life of God's self-giving love - as seen in Christ expressing it in the life of the Black church. Cone (1997:66) supports the notion that God stands with the poor, powerless and trampled upon:

"Where Christ is, there is the Church." Christ is to be found, as always, where men (human beings) are enslaved and trampled underfoot; Christ is found suffering with the suffering; Christ is in the ghetto -there also is his church.

The critical question is: Which "god" is giving love? From the URCSA perspective and confessional basis, it is not difficult to answer this critical question, because the URCSA knows only one God, the God of Article 4 of the Belhar Confession, the "God of the poor", the God who stands with the poor, and the Black church should stand where God stands through the Word and deed; the church should engage in all spheres of life for the people of God.

3. UNITING REFORMED CHURCH IN SOUTHERN AFRICA AS A BLACK CHURCH

The fact that the URCSA emerged as a fundamental part of Black people resisting racial oppression qualifies it to be a Black church. Being a Black church does not mean that the URCSA is a racist church or exclusively the church for the Black people of Southern Africa, but it is an inclusive church and a home for all those who have experienced the history of, and were prepared to resist racial oppression. Some White people have found a home in this Black church, due to its hospitality. Dr Beyers Naude, Profs Nico Smith, Gerrie Lubbe, Klippies Kritzinger, Willem Saayman, C Landman and many more White people have made this church more Black in terms of resistance to racial oppression. Article 3 of the URCSA's Church Order confirms that this church is a Black church, but it is simultaneously an inclusive church. Article 3 states that "[b]elief in Jesus Christ is the only condition for membership of the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa". There is a need to qualify the Christ mentioned in Article 3: He is the very same God we confess in the Belhar Confession, the "Triune God" of Article 1, and the very same Triune God of Article 4:

We believe that God has revealed himself as the One who wishes to bring about justice and true peace among men; that in a world full of injustice and enmity He is in a special way the God of the destitute, the poor and wronged and that He calls his church to follow Him in this; that He brings justice to the oppressed and gives bread to the hungry; that He frees the prisoner and restores sight to the blind; that He supports the downtrodden, protects the stranger, helps orphans and widows and blocks the path of the ungodly; that for Him pure and undefiled religion is to visit the orphans and the widows in their suffering; that He wishes to teach His people to do what is good and seek the right. That the church must therefore stand by people in any form of suffering and need, which implies, among other things, that the church must witness against and strive against any form of injustice, so that justice may roll down like waters, and righteousness like [an] ever-flowing stream; that the church as the possession of God must stand where He stands namely against injustice and with the wronged ... in the name of the gospel.

The Black church is the church of the God of the poor, of justice, and of peace. The church is an inclusive church, because it consists of marginalised people who have experienced racial oppression and suffering.

The Black church is a classless society or community; this is the characteristic of the URCSA in terms of its church order in Article 4. Articles 4.2 and 4.3 state the following:

The believers accept mutual responsibility for one another in their spiritual and physical needs. The congregation lives as a family of God where they are inextricably bound to one another and where they mutually share joy and sorrow. Each considers the other higher than him/herself and no one only cares about his/her own needs, but also about the needs of others. In this way they share one another's burdens and fulfill the law of Christ. The congregation's service to humankind and the world consists in proclaiming God's reconciling and liberating acts in and for the world, living out Christ's love, calling humankind to reconciliation with God and reconciliation and peace amongst one another. The congregation serves God, who in a particular way is the God of the suffering, the poor and those who are wronged (victimized), by supporting people in whatever form of suffering and need they may experience, by witnessing and fighting against all forms of injustice; by calling upon the government and the authorities to serve all the inhabitants of the country by allowing justice to prevail and by fighting against injustice. The congregation serves God by witnessing against all rulers and those who are privileged who out selfishness seek their own interest and who have power over others and who do them wrong (URCSA 2012a).

It is unfortunate that there are people, within the church of unity, love and reconciliation, who live alongside the legal, moral and confessional obligations. This is confessed in Article 26 of the Belgic Confession (1567:15):

We believe that we ought diligently and circumspectly to discern from the Word of God which is the true Church, since all sect[s], which are in the world assume to themselves the name of the Church. But we speak not here of hypocrites, who are mixed in the church with good, yet are not of the church, though externally in it; but we say that the body and communion of the true church must be distinguished from all sects that call themselves the church.

The URCSA is also experiencing what is confessed in this article, namely that there are good and bad people in the Black church. This is evidenced in the fact that there is failure in terms of the ministers of the Word and Sacraments in the URCSA living and working under fear of other church council members, whom the researcher classifies as the hypocrites mentioned in Article 26 of the Belgic Confession. The reason for living and working under fear is that there is a new spirit among the church councils who feels that they are employers of the ministers. Once one speaks of employer-employee relationship, there is a class of the "have" and the "have not", the master and the slave relationship. A challenge directed to my colleagues and fellow equals (governing elders) before the eyes of God is to go back to basics and be members of the Black church in the real sense of the word, the classless community, the church of the people who have experienced oppression, and the church that is not prepared to go back to what the oppressors did to these men of God during the apartheid era. In his article, Desmond Tutu (2012:483-484) mentions the following:

The history of Rwanda was typical of a history of "top dog" and "underdog". The top dog wanted to cling to its privileged position and the underdog strove to topple the top dog. When that happened, the new top dog engaged in an orgy of retribution to pay back the new underdog for all the pain and suffering it had inflicted when it was top dog. The new underdog fought like an enraged bull to topple the new top dog, storing in memory all the pain and suffering it was enduring forgetting that the new top dog was in its view only retaliating for all that [it] remembered it had suffered when the underdog had been its master.

This situation prevails in the URCSA in the new dispensation. In the old dispensation, the minister of the Word and Sacraments was the master and compendium of knowledge in the figure of the White body, inheriting the culture of the missionaries. The democratic era has introduced the democratic way of handling issues in the church, where decisions are taken by means of debates and votes. The rule of the day is that the majority wins, and this leads to tyranny of majority where one powerful member through debate will persuade the others to vote with him/her without discerning the will of God. If the attitude of the "top dog" and the "under dog" prevails in the URCSA, the church needs to rediscover herself as a Black church with the Ubuntu principle.

The Black church is the church of Ubuntu where "Motho ke motho ka batho ba bangwe". Ubuntu can be translated as follows: a human being is a human being because of other human beings and because they are created in the image of God. These relationships provide the most prolific, the most profound, and the most intense source of motivation for living and for action (Gaillardetz 2008:127).

A Black church is a church of Ujamaa, because of its unity and brotherhood or sisterhood. Onwubiko (2001:36) explains that the concept of Ujamaa, properly understood as "togetherness", "familyhood", does not depend on consanguinity. It depicts a "community spirit" of togetherness, which regards all people as 'brothers and sisters'. This community spirit, in turn, shapes distinctive African understandings of personhood. In the majority of African societies, there is hardly a sense of individual autonomy:

Martin Luther said to the German people: "If God is your Father, the church is your mother." The [B]lack theologian can correctly point to the [B]lack church as a family of God for those E. Franklin Frazier refers to as "homeless women and roving men." Separating families during slavery was followed almost at once by scattering of families during the migration to urban centers. This has been followed by a welfare system that almost finished off the possibility of a strong family system among [B]lacks. The recovery of a meaningful family life for [B]lacks is one of the greatest challenges facing the [B]lack church and its ministry to [B]lack people. The task may seem more hopeful if we remember that [the B]lack church was a family for [B]lacks when there was no organised family (Roberts 2005:27).

Hence, as a reformed and African church, the URCSA confesses and confirms this oneness or togetherness through its Belhar Confession and Church Order, as stated in Article 4.3 of the Church Order (2012a:5):

The believers accept mutual responsibility for one another in their spiritual and physical needs. The congregation lives as a family of God where they are inextricably bound to one another and where they mutually share joy and sorrow. Each considers the other higher than him/herself and no one only cares about his/her own needs, but also about the needs of others. In this way they share one another's burdens and fulfil the law of Christ.

If the Black church is the community of the oppressed and poor people, and the God of this community is the God of the Belhar Confession, then it is important to scrutinise the relevancy of this God of the Belhar Confession. The only instrument to gauge this relevancy is to investigate the poverty level in South Africa 21 years after democracy.

4. POVERTY LEVEL IN DEMOCRATIC SOUTH AFRICA

A depiction of poverty based on race in the context of the present study is in order. It is important to observe that Black South Africans predominantly experience poverty compared to persons from other racial groups. On average, 4.35% of White persons are poor in comparison to 61.4% of poor Black African people (Stats SA 2012:71). The margins are obvious. In addition, such margins reveal an unsettling racial dimension of poverty in South Africa, which will later be premised in the discourse of land and the Land Act of 1913, in particular. The previously disadvantaged Black Africans, during the colonial and apartheid regimes, continue to be poor in post-apartheid South Africa. In the church's view, partly because of the present reality of poverty among Black Africans and due to the loss of land (assets) in the colonial and apartheid regimes, poverty and the lack of assets are worth discussing and exploring (Modise & Mtshiselwe 2013).

Carter and May's location of the discourse on the dynamics of poverty within the notion of the possession of assets in South Africa is relevant in the present study. They are of the opinion that poverty can be alleviated when the poor accumulate productive assets such as land (Carter & May 2001:1990-1991). This view is grounded in the concept of asset poverty line. Such a concept presupposes that a household and/or an individual requires minimal assets in order to escape poverty. Despite Carter and May's limitation on quantifying and/or asserting the exact minimal assets required to avoid poverty, they manage to reveal the dependency of poverty alleviation on the accumulation of land.2 Failure to acquire land (assets) permeates a situation wherein the previously disadvantaged poor Black South Africans are trapped in poverty. Such a situation leads to a discussion of the concept of chronic poverty.

5. BLACK CHURCH AS CARING COMMUNITY

If the URCSA is a Black church in terms of its origin, membership, praise and worship, it can proudly be stated that the URCSA needs to be a caring community. A caring faith community goes beyond prayer; it believes in actions. It is a church of "active faith".

The church has a role to play in modern society, because the church is led by people from the communities, who have been a part of communities for as long as they have lived and are, in fact, the character inspired by the experiences gathered from communities. Likewise, the church's membership comes from the communities served by the church. These congregation members define the essence and reflect the character of their communities. Thus, although the church might have a spiritual responsibility towards the community, it must find its identity within the communities within which it exists (Mokoto & Nhlopo 2008:14).

This is the position of the URCSA, as dictated by Article 4 of the Belhar Confession (1986):

The church believes that God has revealed Godself as One who wishes to bring about justice and true peace among people; that in a world full of injustice and enmity God is in a special way God of the destitute, the poor and the wronged but that God calls the church to follow in this; that God brings justice to the oppressed and gives bread to the hungry; that God frees the prisoners and restores sight to the blind; that God supports the downtrodden, protects the strangers, helps orphans and widows and blocks the path of the ungodly; that for God pure and undefiled religion is to visit the orphans and the widows in their suffering; that god wishes to teach the people of God to do what is good and seek the right; that the church must therefore stand by people in any form of suffering and need, which implies, among other things, that the church must witness against and strive against any form of injustice, so that justice my roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream; that the church belonging to God, should stand where God stands, namely against injustice and with the wronged; that in following Christ the church must witness against all powerful and privileged who selfishly seek their own interests and thus control and harm others.

The church that confesses this confession should go beyond prayer in its services and practices.

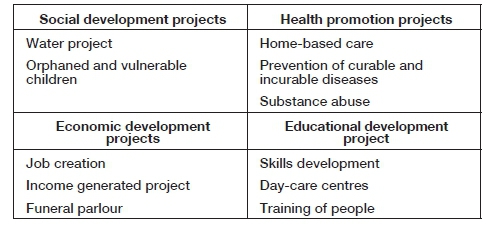

Article 5 is divided into the three core ministries of the URCSA, namely proclamation and worship, congregational ministry, as well as service and witness. The ministry of proclamation and worship focuses more on prayers and teachings of the church. The second ministry of congregational ministry is more of a mechanism that translates the proclamation and worship into practice. The third ministry of service and witness addresses the practical exercises of the church (URCSA 2012b). On the agenda of the General Synod of 2012 in Namibia, the ministry for service and witness reported the following projects:

For this to happen, there is a need for a very strong service and witness ministry in the Synod, that will bring the service to the church and the world, as stated in the URCSA Church Order Article 4.1.

6. BLACK CHURCH AND ITS MINISTERS OF THE WORD AND SACRAMENTS

The caring community needs to think twice when dealing with the minister of the Word, faith leader, and faith consultant. The following is crucial:

• Respect for the call of God to these men and women of God.

• Provision for spiritual and physical needs (care-givers' wellness).

• Financial and material support: good benefits during their tenure as ministers. When they retire from the ministry, a pension package should motivate a minister to retire.

6.1 Generation gap (programmes for induction, orientation, and mentorship for new ministers)

Mentoring is particularly valuable for ministerial and managerial development, to provide guidance, advice and tutoring to less experienced individuals. The introduction of peer-mentoring may become more feasible in the 21st-century organisation where fewer hierarchical layers impact on the availability of mentors. In our situation as ministers of the Word and the Church, in general, the availability of mentors is due to capacity in terms of vacant congregation and the tent-making ministry system, therefore the peer-mentorship will do (Coetzee & Schreuder 2010:433). Preference should be given to the senior-junior ministers mentorship,3 because this will create a sound relationship between senior and junior ministers, as well as a two-way traffic of skill and knowledge transfer during the process. It will assist the church to close the generation gap. The church in this region through its service and witness ministry under its pastoral care needs to provide the space and budget for such programmes.

6.2 The winding-down period for senior ministers who are about to retire

The caring community needs to have a clear plan for its retiree beforehand; this means that there must be a retirement preparation programme. Coetzee and Schreuder (2010:433) indicate that retirement preparation programmes are directed at the target population of people approaching retirement from work and about to leave the organisation. Their aim is to ease the transition of the older colleagues from full working life into retirement, and this usually consists of several elements, from financial considerations, leisure, health, and contact with the organisation and other bodies such as support groups after retirement. It will not be proper for the church to lessen the workload of the minister of the Word, who is in the winding-down period for retirement, while the church still struggles to address the challenge on vacant congregations, tent-making ministry, and very few candidates for ministry who will fill the posts left by the retired ministers. Coetzee and Schreuder (2010:56-57) also document the solution to these challenges:

One survey calls the 'aging workforce' the biggest demographic trend impacting employers. For example, how will employers replace these retiring employees in the face of diminishing supply of young workers? Employers are dealing with this problem in various ways. Desseler (2009) reports the findings of a survey which observed that 41% of surveyed employers are bringing retirees back into the workforce, and 31% are offering employment options designed to attract and retain semi-retired workers. This retiree trend helps explain why 'talent retention' or getting and keeping good employees, ranks as companies' top concern.

This shows that there is a tendency in the corporate world to retain retirees, due to a shortage of supply of young workers. A similar situation faces the URCSA as the Black church; thus, the need to copy the best practice from the corporate world, hence the provision for relief ministers in the church order and regulations of the General Synod after a minister has reached the pensionable age.

The Black church needs ministers who will be very vigilant on issues that affect the entire community. The caring community needs to provide forums that will empower their ministers to be vigilant and well informed on current issues (the outcry for BK's4 revitalisation to address the Black church issues).

7. CONCLUSION

The Black church, as part of the universal church, needs to be visible fellowship, an institution, an organisation with economic, social, and political influence. It is the only largest organisation owned and controlled by Black people in a White multicultural racist society.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Belgic Confession 1567. In this we believe, thus we confess. Johannesburg: Andrew Murray Congregation of the DRC. [ Links ]

Belhar confession 1986. Belhar. Cape Town: CFL Publishers. [ Links ]

Best, T.D. 2002. Christ divided: Liberation, ecumenism and race in South Africa. Pretoria: Unisa Press. [ Links ]

Carter, R. & May, J. 2001. One kind of freedom: Poverty dynamics in post-Apartheid South Africa. World Development 29(12):1987-2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00089-4 [ Links ]

Coetzee, M. & Schreuder, D. 2010. Personnel psychology: An applied perspective. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cone, J.H. 1997. Black theology and Black power. New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Dessler, G. 2009. Fundamentals of human resource management. London: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Douglas, K.B. 2012. Black bodies and the Black church: A blues slant. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137091437 [ Links ]

Gaillardetz, R.R. 2008. Ecclesiology for a global church: A people called and sent. New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Gutierrez, G. 1988. A theology of liberation. New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Hopkins, D.N. 1999. Introducing Black theology of liberation. New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Lindgren, A.J. 1965. Foundations for purposeful church administration. Nashville, TN: Abingdon. [ Links ]

Mdingi, H.M. 2014. What does it mean to be human? A systematic theological reflection on the notion of a Black church, Black theology, Steve Biko and Black consciousness with regards to materialism and individualism. Unpublished masters dissertation. Pretoria: University of South Africa [ Links ]

Modise, L.J. & Mtshiselwe, N. 2013. The Native Land Act of 1913 engineering of poverty of Black Africans: A historico-ecclesiastic perspective. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 39(2):359-378 [ Links ]

Mokoto, M. & Nhlopo, M. 2008. Religion within the context of South Africa's developmental agenda: Faith-based organization summit. Rustenburg: North West Social Development. [ Links ]

Onwubiko, O.A. 2001. The church in mission in the light of Ecclesia in Africa. Nairobi, Kenya: Pauline Publications Africa. [ Links ]

Roberts, J.D. 2005. Liberation and reconciliation: A Black theology. 2nd edition. Louisville, KY: John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa (Stats SA)2012. Social profile of vulnerable groups in South Africa 2002-2011. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. [ Links ]

Tutu, M.D. 2012. Without forgiveness there really is no future. In: W.T. Cavanaugh, J.W. Bailey & C. Hovey (eds), An Eerdmans reader in contemporary political theology (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans), pp. 474-484. [ Links ]

Uniting Reformed Church of South Africa (URCSA) 2012a. Church Order. Cape Town: CLF Publishers [ Links ]

________. 2012b. General Synods Acts. Pretoria: URCSA Northern Synod. [ Links ]

1 This article is the product of a keynote address during the Long-Service Award ceremony of the URCSA, Southern Synod, and is meant to be presented at the Black Theology Conference, Unisa.

2 Poverty alleviation is not only dependent on the accumulation of land. Such accumulation forms an integral part of mechanisms to alleviate poverty.

3 Senior and junior, not in terms of position, but in terms of years of service.

4 Belydende Kring (Confessional Circle) was the movement of the ministers and elders of the former Dutch Reformed Church in Africa (DRCA), DRC for Blacks, and Dutch Reformed Mission Church (DRMC) for Coloureds.