Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.36 supl.24 Bloemfontein 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v36i1.5s

ARTICLE HEADING

Reclaiming our black bodies: reflections on a portrait of Sarah (Saartjie) Baartman and the destruction of black bodies by the state

I.D. Mothoagae

Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies, University of South Africa. mothodi@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The parading of the nude body of Sarah Baartman by the British colonisers led England and France to racially categorise her as a subhuman. Her Black body was viewed as something that can be violated, exploited, destructed, penetrated, and subjugated to various inhumane conditions. According to Fanon, there is a world order that determines who fits where and how: "The colonial world is a world cut in two". The militaristic response by the state to the people's protest point to the fact that technology, the regimes, and the targets still remain. In this article, I will argue that the use of violence by the colonial, imperial system against Sarah Baartman (Black people) has its origins in colonialism and slavery. I maintain that there is a distinction between "a body" and "the Body". The paper will use as basis the intersectionality theory. Conclusions will be drawn.

Keywords: Race, Epistemic, Gender, Dehumanisation, Sara Baartman

Trefwoorde: Ras, Epistemies, Geslag, Dehumanisering, Sara Baartman

The biggest mistake the [B]lack world ever made was to assume that whoever opposed apartheid was an ally (Biko 1987:63).

1. INTRODUCTION

The story of Baartman is narrated in colonial historiography. Her legacy has impacted on the current representations and construction of African women in the twenty-first century. Furthermore, colonial historiography is crucial in understanding the notion of the image of God within the Eurocentric (a)historical narratives of Baartman. It is within these narratives that the implicit racist and sexist development of European language is employed, not solely with Baartman, but also contemporaneously with the bodies of Black women, focusing predominantly on the "anomaly of their hypersexual" genitals (Gordon-Chimpembere 2011:5). Fanon (1963:29) summarises Gordon-Chimpembere's statement as follows:

In the colonies it is the policeman and the soldier who are official, instituted go-betweens, the spokesmen of the settler and his rule of oppression ... In the colonial countries, on the contrary, the policeman and the soldier, by their immediate presence and their frequent and direct action, maintain contact with the native and advise him by means of rifle-butts and napalm not to budge.

The killing of Moses Tatane, the Marikana massacre, and the militaristic response of the state to the people's protests on service delivery, # feesmustfall, #Rhodesmustfall, etc. suggest possible propositions that the struggle for justice against apartheid in South Africa and the civil rights movement in the United States failed. It is my contention that the struggle for justice was successful in what it achieved, namely the legal eradication of racism and the dismantling of apartheid in both South Africa and the United States. Davis (2016:16) maintains this view:

So we don't have to stop at the era of the civil rights movement, we can recognize that practices that originated with slavery were not resolved by the civil rights movement. We may not experience lynchings and Ku Klux Klan violence in the same way we did earlier, but there is still state violence, police violence, military violence. And to a certain extent the Ku Klux Klan still exists.

Davis' statement points to the notion that state violence does not end because of certain events in the history of the people - for example, the end of the so-called end of apartheid, or the repatriation of the bodily remains of Sarah Baartman. Rather, there seems to be a continuation of how certain bodies are treated by the state. It is for this reason that I follow Davis' (2016:19) definition of intersectionality:

So, behind this concept of intersectionality is a rich history of struggle. ... Initially intersectionality was about bodies and experiences. But now, how do we talk about bringing various social justice struggles together, across national borders?

This definition compels us to do theology not from only our particular context, but rather to observe connections across the world so that theological analysis not only becomes localised, but also breaks borders.

The hierarchy of being is constructed in such a way that there is a distinction between "human life" and "Black life", as in the works by scholars such as Bernth Lindfors (2014); Sadiah Qureshi (2004) Simone Kerseboom (2011); Jean Young (1997), and Zine Magubane (2001), to name but a few. Magubane (2001:816) states the following regarding the construction of body:

Any scholar wishing to advance an argument on gender and colonialism, gender and science, or gender and race must, it seems, quote Sander Gilman's (1985) "Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and Literature". First published in a 1985 issue of Critical Inquiry, the article has been reprinted in several anthologies. It is cited by virtually every scholar concerned with analyzing gender, science, race, colonial- ism, and/or their intersections.

It is within this context that we need to understand the concept of the image of God, which is an attempt to distort the theological notion. It is for this reason that, according to Magubane (2001:816-817),

Gilman uses Sarah Baartman, the so-called Hottentot Venus, as a protagonist in showing how medical, literary, and scientific discourses work to construct images of racial and sexual difference.

According to this hierarchy, "human life" is valuable, while "Black life" is valueless. Underpinning this is the ontological conceptualisation of being as the Imago Dei (made in the Image and likeness of God). Western philosophy and theology reinforced the concept of Imago Dei as pertaining to whiteness. For this reason, according to Boesak (2015:26), the Black church responded in numerous ways to Western theology:

The [B]lack church rejected the anemic, inadequate theology of accommodation and acquiescence, of individualistic, otherworldly spirituality foisted upon us by western Christianity that taught us to accept the existing unjust order as God-ordained. We embraced, rather, what we called a "theology of refusal," a theology that refused to accept God as a god of oppression, but rather a god of liberation who calls people to participate actively in the struggle for justice and liberation.

Boesak's argument is the Black church's attempt to reclaim the concept of Imago Dei as not exclusive to a particular "race", but rather as inclusive of all people regardless of the colour of their skin. For this reason, according to Boesak (2015:25), the South African Council of Churches (SACC) stated in 1979 that the

church knows that the God of the exodus and the covenant, the God of Jesus of Nazareth, was different from the God [W]hite Christianity was proclaiming.

It is within this context that the concept of the Imago Dei is used as a discursive tool in making whiteness a norm. Vice's (2010:323) question about what it means to be White in South Africa has accrued all the privileges that come with being White:

At the same time, our equally famous history of stupefying injustice and inhumanity feels still with us: its effects press around us every day, in the visible poverty, the crime that has affected everyone, the child beggars on the pavements, the de facto racial segregation of living spaces, in who is serving whom in restaurants and shops and in homes.

Vice argues further that the advantages that are accrued to whiteness are usually termed "privileges". According to her, "privileges", for example, often refers to goods that one cannot expect as one's due; as a result, one does not have a right to those goods. Therefore, it is clear that the many ways in which Whites are advantaged are, in fact, ways that all people should be able to expect as their due. It can thus be mentioned that "privilege" suggests the sense of unearned, unshared, non-universal advantages. Biko (1987:66) argues about White privilege as follows:

It is not as if [W]hites are allowed to enjoy privilege only when they declare their solidarity with the ruling party. They are born into privilege and are nourished by and nurtured in the system of ruthless exploitation of [B]lack energy.

While whiteness has the privilege to oppress, penetrate, enslave, study, objectify, give and take life, and infuse a soul, in other words, make non-being into Being, Black life is viewed as valueless. Wilderson III (2008:98) states the following on the notion of value:

Human value is an effect of recognition that is inextricably bound with vision. Human value is an effect of perspectivity. What does it mean, then, if perspectivity, as the strategy for value extraction and expression, is most visionary when it is White and most bland when it is Black? It means that "to be valued [is to] receive value from outside of blackness".

Wilderson III's argument is critical in understanding how Blackness is understood by the dominant race. An example of this is how "Black life" is devalued throughout the world (Somalia, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Nigeria). The Western countries' response to Ebola also points to the devaluing of Black life as Absence. In recent years, state violence (police brutality) across the United States, Britain, and South Africa has sparked Blacks to realise that Black life has been under violent attacks by the imperial, colonialist, capitalist, patriarchal system in the name of 'democracy' and human rights. Davis (2016:17-18) summarises this view well:

Well, what's also interesting in South Africa is the fact that many of the positions of leadership from which Black people were of course totally excluded during apartheid are now occupied by Black people, including within the police hierarchy. I recently saw a film on the Marikana miners, who were attacked, injured, and many killed by the police. The miners were Black, the police force was Black, the provincial head of the police force was a Black woman. The national head of the police force is a Black woman. Nevertheless, what happened in Marikana was, in many important respects, a reenactment of Sharpeville. Racism is so dangerous because it does not necessarily depend on individual actors, but rather is deeply embedded in the apparatus ... the technology, the regimes, the targets still the same. I fear that if we don't take seriously the ways in which racism is embedded in the structures of institutions, if we assume that there must be an identifiable racist.

In incidents such as the one that took place on 13 April 2011 in a small town called Setsoto Municipal Offices in Ficksburg, Free State, policemen murdered Moses Tatane (Tromp et al. 2011). These policemen were later acquitted. Another example of police brutality is the dragging behind their vehicle of a Mozambican taxi driver. According to the Mail & Guardian report, the issue arose between Macia and the police after he argued with them about parking his taxi. The video shows the 27-year-old being assaulted. He was tied with his back to the vehicle and then dragged behind the police van. Thirteen years ago, a group of four White men murdered a Black homeless man in cold blood and left him to die. They served five and a half years of their 12-year sentence in prison (Sosibo 2014). As mentioned earlier, state violence does not end because of certain events in the history of the people - for example, the end of the so-called end of apartheid. The examples indicate that there seems to be a continuation of how the State treats certain bodies.

All of these events in history indicate that Blacks are void of Presence, and cannot embody value; they are void of perspectivity, and cannot bestow value. In short, Blacks cannot be. Their mode of being becomes the being of the No.

2. THE MAKING OF BODIES

The European expansion and conquest resulted in the construction of "body" based on the notion of race. Travellers, missionaries, slave traders, and plantation owners obscurely narrated stories about Africans, their physical appearance, social hierarchies, religion, as well as socioeconomic and political status. To these European writers, Africans possessed inferior faculties based on the assumption that they are racially different, unintelligent, animal-like, without a soul, pagan, savage, and uncivilised (Moffat 1842:244). Such a stereotype narrative about Africans was linked to misconceptions, rumours, and lies. The outcome of this was that people who never went to Africa and met Africans accepted these stories as truth and were cited in scientific literature of the day. It can be argued that it was through such narratives that the construction of "a body" and "the body" was facilitated. Philosophers such as Hegel and Renè Descartes philosophically constructed the notion of "a body" and "the body". Magubane in his paper Social Construction of Race and Citizenship in South Africa at a conference a on Racism and Public Policy (2001:3) referring to Hegel Magubane states the following:

Africa is in general a closed land, and it maintains this fundamental character. It is characteristics of the Blacks [author's emphasis) that their consciousness has not yet even arrived at the intuition of any objectively, as for example, of God or the law, in which humanity relates to the world and intuits its essence. He [the Black person] is a human being in the rough.

In contextualising the concepts of "the body" versus "a body", I would argue that the definition of racism resides in these two concepts. Naicker (2012:209) supports this view:

By the early 19th century the study of eugenics provided a scientific brand of racism which emphasized the supposed biological dangers of "race mixing" and termed it miscegenation. Scientific racism can be defined as the belief that the variables of phenotype, intelligence, and ability to achieve in terms of civilization and/or culture are not only genetically determined, but also genetically linked. Influential scientists in the field warned that racial mixing was a social crime which would lead to the disappearance of White civilization and must, therefore, be quelled.

Furthermore, the continuous destruction of Black Bodies is to be understood within the narrative of a penetrable body and a non-penetrable body. In other words, since they represent the missing link between men and brutes, Black Bodies can be subjected to any form of violence, be displaced, penetrated, subjugated, and paraded as a form of entertainment. It is within this notion of "a body" that the Black Body is "Othered" as an object of study.

Maldonado-Torres (2007:253) summarises Fanon's concept of zone of nonbeing as follows: "For Fanon, [B]lack is not a being or simply nothingness, the Black is something else".

Just as there were different species in the animal world that could be characterized in their hierarchical order of supremacy, so too, were different the diversities of men and women who could be classified as inferior and superior. The body belongs to the zone of being, because "the body" embodies higher faculties, has a soul, is intelligent, and thus non-penetrable; it cannot be subjected to any form of violence, displacement, or subjugation. Maldonado-Torres (2007:242) further argues:

Fanon's critique of Hegel's ontology in Black Skin, White Masks not only provide[s] the basis for an alternative depiction of the master/ slave dialectic, but also contributes to a more general rethinking of ontology in light of coloniality and the search for decolonization.

Naicker (2012) traces the development of the making of body. She argues that Prof. Johann Blumenbach (1752-1840) coined the notion that the people of Europe belonged to one race. Naicker (2012:209) states that Prof. Blumenbach, a pioneer in the study of comparative anatomy and skull analysis, maintained that Europeans represented the highest racial type in the human species. Sutton (2007:22-23) substantiates Naicker's analysis, stating that, in 1855, Blumenbach's counterpart, Joseph-Arthur Comte de Gobineau, also claimed that it is a historical fact that all civilisations are derived from the White race. The White race [Whiteness] is noble, great and brilliant only so far as it preserves its "pure" blood and that it is the various admixtures of blood that are responsible for the degeneration of the "pure" race. In 1859, the British naturalist Charles Darwin published a book titled the Origin of species, in which he provides a comprehensive concept that an individual's ability to survive and reproduce was dependent on a natural selection of inherited variations.

In the 1880s, according to Naicker, Sir Francis Galton coined the term "eugenics" to mean "well-born". The science of eugenics was developed as an off-shoot of the Darwinian Theory. This theory led to Galton's claim that biologically inherited leadership qualities determined the social status of the British ruling class. As a result, the notion of "inferior types", European superiority and the need to control human heredity has preoccupied eugenicists since then (Naicker 2012: 209). Montagu (1997:80) supports Naicker's view and argues that Grant Madison, in his influential book The passing of the great race, affirmed that the offspring of mixed marriages transmits "impure" blood into the White race and, if allowed to continue, would ultimately rob the White race of its hereditary "purity".

Montagu further states that, throughout the 19th century, hardly a handful of voices were raised against the notion of a hierarchy of races. Sociology, anthropology, biology, psychology, and medicine became instruments used to prove the inferiority of various race groups in comparison to the White race. Fanon refers to this as the "zone of being" and the "zone of non-being". This can be summarised as follows:

Racialization occurs through the marking of bodies. Some bodies are racialised as superior and other bodies are racialised as inferior. The important point here is that those subjects located above the line of the human, as superior, live in what Afro-Caribbean philosophers following Fanon's work called the "zone of being", while subjects that live on the inferior side of the demarcating line live in the "zone of non-being" (Grosfoguel 2014:4).

It can thus be argued that the 19th century was a period when scientific racism held the status of a "normal' science. Within the scientific community, the basic tenets of scientific racism met with hardly any opposition. This newly established racial order was used to justify European dominance, paternalism, and imperialism. It also guaranteed European men the status of being the highest rank in terms of race, class, and gender, and set the stage for racial formation in European colonies (Naicker 2012:209). In other words, as Wilderson III (2008:98) puts it, the world cannot accommodate a Black(ened) relation at the level of bodies [subjectivity]:

Thus, Black 'presence is a form of absence' for to see a Black is to see the Black, an ontological frieze that waits for a gaze, rather than a living ontology moving with agency in the field of vision. The Black's moment of recognition by the Other is always already Blackness, upon which supplements are lavished - American, Caribbean, Xhosa, Zulu, Motswana, Sotho (my italics).

In his analysis of Fanon, Maldonado-Torres (2007:242) maintains Wilderson III's argument:

Fanon's critique of Hegel's ontology in Black Skin, White Masks not only provide[s] the basis for an alternative depiction of the master/slave dialectic, but also contributes to a more general rethinking of ontology in light of coloniality and the search for decolonization.

It can be said that the construction of being, based on 19th-century ideology, continues to locate Blackness with Absence and Whiteness with Presence. Wilderson III (2007:98) illustrates this view in his argument:

For not only are Whites "prosthetic Gods," the embodiment of "full presence", that is, "when a White is absent something is Absent," there is a "lacuna in being," as one would assume given the status of Blackness but Whiteness is also "the standpoint from which others are seen"; which is to say Whiteness is both full Presence and absolute perspectivity.

The Theology of Predestination demonstrates Wilderson III's argument. Based on the construction of Whiteness as the Imago Dei (Image of God), hence the idea I think therefore I am, Blackness was viewed as the missing link between animals and "beingness", as understood in the context of Whiteness as the image and likeness of God. Maldonado-Torres (2007:245) supports this view in his analysis of Descartes:

Dussel suggests as much: 'The 'barbarian' was the obligatory context of all reflection on subjectivity, reason, the cogito'. But the true context was marked not only by the existence of the barbarian, or else, the barbarian had acquired new connotations in modernity.

It is imperative to point out at this point that, as mentioned earlier, the notion of the image of God is adapted and isolated from its theological meaning. It is in the isolation of the concept that the notion is then used as racial marker. The separation of the concept created whiteness as a norm, a measuring tool whereby humanity is determined. Theological terms and concepts in this sense became a vehicle for supporting what Grosfoguel (2014:6) refers to as "the Hegelian dialectic" characterizes the "I" and the "Other". In the "I" and "Other" dialectic within the zone of being there are conflicts; but these are non-racial conflicts, as the oppressor "I" recognizes the humanity of the oppressed "Other"'.

Whiteness then has the authority to infuse a soul into a Black Body. The infusion of a soul into a Black Body cemented the ideology that, because Black Bodies do not have a soul, they can be subjected to any form of subjugation. In other words, Black Bodies remain the "Other" (Absent), while their Presence came into being through the infusing of a soul, Whiteness.

This happened mostly for sexual gratification; when that happens, a Black Body becomes disposable. I (Mothoagae 2012) have argued that Black Bodies were viewed as soulless bodies; their humanity was and continues to be denied based on such a premise. I (Mothoagae 2012:280) will later argue that the narrative about Sarah Baartman elucidates this point. Furthermore, in the United States, slaves were read biblical texts that authenticated slavery and that it was by God's design that Black Bodies are sons and daughters of Ham and must be servants of Whites for eternity. The reason for this is that Whiteness as a race is constructed on the basis of the superlative. McKaiser (2011:453) asserts the following:

It is important to get a precise handle on 'Whiteness'. Whiteness refers to the occupation of 'a social location of structural privilege in the right kind of racialized society', as well as seeing the world 'whitely'.

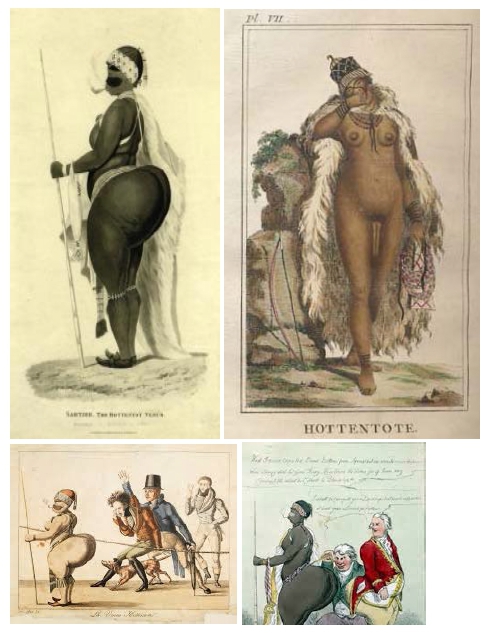

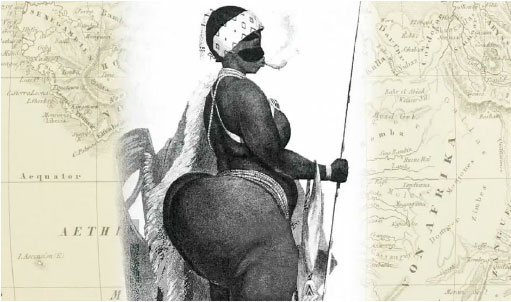

As I will show in the next section, the colonialist approach to Black people was on the basis of their social location, implying that they are superior and that Black people are inferior. The story of Sara Baartman, the humiliations, the devaluing and sexualising of her body as well as naming her "Hottentot Venus" (see Appendix 1), is what McKaiser refers to as structural Privilege of Whiteness and Absence of Blackness. To use Fanon's narrative, the portraits of Sara Baartman represent the distinction between those in the zone of being and those in the zone of non-being.

3. THE CONSTRUCTION OF SARAH BAARTMAN'S IMAGES THROUGH THE EYES OF THE SUPERLATIVE

Sarah Baartman is yet another example of the conqueror's inhumanity towards the indigenous conquered peoples. The narrative about where she was born and how she arrived in Europe has been well documented. For the purposes of this article, I will not endeavour to attempt to outline what scholars such as Bernth Lindfors (2014); Sadiah Qureshi (2004); Simone Kerseboom (2011); Jean Young (1997), and Zine Magubane (2001) did.

It is critical to contextualise the parading of Sarah Baartman. Her story is written from a European perspective, with a specific agenda to support White hegemony. It is also crucial to contextualise the 19th-century world view, which operated on "Subject" and "Object". The "Subject" produces knowledge, while the "Object" is studied by the "Subject". It is said that Saartjie Baartman willingly agreed to go to Europe in order to make money. Furthermore, she was a slave; the right to choose to go or not to go was limited or not there at all. From the very beginning she was an object of study, something she was not aware of. She was meant to make money for the slave owner, as the coloniser owned her entire being by virtue of her being an "Object" slave. In this instance, one can mention the earlier arguments by Maldonado-Torres and Grosfoguel of the "I" and the "Other".

In so doing, one will be able to understand the question: Why her? To arrive at the answer, it is imperative to define racism. Such a definition will enable one to ask uncomfortable questions relating to the social hierarchy of being in the 21st century. Grosfoguel (2014:2) defines racism as a

global hierarchy of superiority and inferiority along the line of the human politically, culturally and economically produced and reproduced for centuries.

It can be argued that racialisation occurs through the marking of bodies. Some bodies are racialised as superior and others as inferior. In the case of Sarah Baartman, besides her Black skin colour as a marker, her physique and anatomy further characterise her as an inferior being. The pictures (see Appendix 1) indicate the following: first, a non-being as an object of study. It is through the drawings and the narratives written about her by the colonisers that the story of Sarah is the manifestation of misguided parody. Sarah was displayed naked for purposes of ridicule; the feigned derision was, in fact, the hidden admiration of the irresistible beauty of the Black woman. Ramose (2007:316) further states that the invitation to Sarah to "display her body" in the first instance, and the rejection of her at the circus lead to her being "a prostitute".

After all, a prostitute who is neither attractive nor skillfully seductive shall have no one to sleep with and will soon be out of business. Her "large genitals", verdurous, fecund and luscious, were beautiful, vibrant and inviting. Only a few declined the invitation. Many could not resist the desire to penetrate her "large genitals" and, under the power of those genitals, their phallic empire collapsed into an orgasmic swoon (Ramose 2007:316). The picture (see Appendix 2) points to the atrocities suffered by people such as Sarah Baartman closely observing the picture, Hartman's (2014: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z8VsTaofizk) definition of pornography resonates with the dehumanisation of Black Bodies as "Absent beings", the "missing link" in the chain of "Being":

Pornography encompasses a variety of discursive and representational practices in which the regard of the other is inseparable from violence and scandalous access. It is [akin to] pornotroping that is the use of the captive body, the thing, the animal as a material and symbolic resource which provides being for the captor by way of conflation, powerlessness, objectification and sexuality and which makes a particular historical incarnation of man the exemplary figure of the human.

In line with Hartman's definition of pornography, Sarah's body was a captive body used to provide the captor (colonialist) with satisfaction. Furthermore, the image portrays her with her legs wide open to satisfy the imaginary needs of the Presence. It is the objectification of her as a body penetrable, conquerable, destructible and Absent. The image also shows how the captor viewed her as an animal:

Unlike Andrew Marvell's 'Coy Mistress', whose long-preserved virginity would spitefully be tried by worms, Sarah Baartman's unpreserved virginity was trampled upon by abusive wild White men. Her 'large genitals' were not tried by worms in Paris because even in her death the beauty and attraction of those genitals was preserved for admiration and adoration by the living and yet-to-be-born sons of the colonial conqueror (Ramose 2007:316).

He further states that blackness has a beauty that surpasses the splendour of the enigmatic beauty of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa. Thus, the treatment received by Sarah Baartman, her displacement as well as the display of her genitals for public view in order to satisfy White man's desire and to feed his imaginary longing to penetrate an African woman was concerned with, among other things, her beauty. Ramose (2007:316) concludes:

The beauty of the black woman is not destined ineluctably to end up in prostitution. Under conditions of slavery or under cover of secrecy, the conqueror failed to resist the beauty of the [B]lack woman.

Her animal-like shadow in the photo illustrates the cosmological, theological, and ideological location of how White men conceived of her being as that of a subhuman. As mentioned earlier, the construction of the Imago Dei by Western philosophy and theology as pertaining to White people or whiteness as human beings and anything outside whiteness as nonhuman, the missing link. The mirror on the photo presents a paradox, that is, first the animal-like shadow; secondly, the image appearing on the mirror is a human being, a Black Body. The face expresses sadness, conflation, powerlessness, objectification, subjugation, and cruelty performed on her Black body.

Under conditions of slavery or under cover of secrecy, the conqueror failed to resist the beauty of the Black woman (Ramose 2007:316). Secondly, a non-being is a sexual object to gratify the master's sexual needs. Thirdly, as Ramose states, the story of Sarah is also a testimony to the brutal, amoral, and lawless slavery that existed in South Africa. This can be summarized as

the colonial conqueror in South Africa shared this trait with other conquerors and predators that depopulated Africa spread over the colonized parts of the world (Ramose 2007:316).

Based on the argument in relation to how Black Bodies are viewed, racism can be defined as:

Depending on the different colonial histories in diverse regions of the world, the hierarchy of superiority / inferiority along the line of the human can be constructed through various racial markers. Racism can be marked by colour, ethnicity, language, culture and/or religion (Mothoagae 2014:13-14; cf. Grosfoguel 2014).

Thus the continual destruction of Black Bodies throughout history, even in the 21st century, is founded on the premise of superiority versus inferiority, colour, ethnicity, language, culture, and religion. All of these can be termed colourism, pigmentation, while others may refer to these as discrimination or prejudice. However, as Grosfoguel points out, the above markers also influence the hierarchy of being. For example, in South Africa during apartheid, various racial markers were used to categorise people according to their race.1 It is for this reason that, according to Grosfoguel (2014), these markers are located within a capitalist/patriarchal/Western-centric/Christian-centric/modern/colonial/world system (Mothoagae 2014:13-14). In the context of the use of military tactics by the police in the Marikana massacre and other protests in this country and in the United States, it can be argued that the system espouses itself as democratic", "nonracist", "non-sexist", "equal", and "justice for all" (Republic of South Africa 1996:1243). Yet, it is within such a system that Black Bodies continue to be brutally destroyed, because to the capitalist, patriarchal, Western-centric, Christian-centric, modern, colonial world system, Black lives do not form part of the hierarchical structure of being. Davis (2016:77) makes the following assertion regarding violence against black people:

Although racist state violence has been a consistent theme in the history of people of African descent in North America ... the sheer persistence of police killings of Black youth contradicts the assumption that these are isolated aberrations.

Davis (2016:81) further states that the historical process of colonisation was a violent conquest of human beings and of the land they stewarded. She maintains that there is a need to identify the genocidal assaults "on the first peoples of this land as the foundational arena for the many forms of state and vigilante violence that followed".

Beckles (2013) gives a compelling argument regarding Britain's repeated denial that indigenous genocide, slave trade, and the institution of slavery were a protracted commercial, governmental, religious, and royal enterprise.

It is for this reason that, in the United States and in South Africa, Black lives do not matter as much as "White lives" - for example, police brutality in the United States and in South Africa, and the Marikana massacre; this is what one can refer to as state violence within a democratic system:

If indeed all lives mattered, we would not need to emphatically proclaim that "Black Lives Matter". Or, as we discover on the BLM website: Black Women Matter, Black Girls Matter, Black Gay Lives Matter, Black Lives Matter, Black Boys Matter, Black Queer Lives Matter, Black Men Matter, Black Lesbians Matter, Black Trans Lives Matter, Black Immigrants Matter, Black Incarcerated Lives Matter ... Yes, Black Lives Matter, Latino/Asian American/Native American/ Muslim/Poor and Working Class White Peoples Lives matter. There are many more specific instances we would have to name before we can ethically and comfortable claim that All Lives Matter (Davis 2016:87).

It is my submission, as I will argue in the next section, that there is a need to problematise the issue of human rights, considering how the system operates and continues to locate Black Bodies.

4. PROBLEMATISING HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE ABSENCE OF BLACKNESS

Throughout history, the brutal killing of Black people has never been a problem for the system. This can be traced back to the beginning of "European expansion" in the name of religion (Christianity). Church leaders sanctioned such atrocities. In the context of South Africa, as Snyman (2005: 327) argues, the Bible became central in the construction of the "Afrikaner" identity and, subsequently, the racial divide of the nation. The brutal killing of Black people has never been an issue of human rights; it is for this reason that Davis (2016: 77) argues that "racist state violence has been a consistent theme in the history of people of African descent".2Since conflicts with the superlative elites and ruling class within the zone of being are non-racial, one notes that, in the conflicts of class, gender and sexuality, the "Other Being" shares in the privileges of the imperial codes of law and rights, the emancipation discourses of the Enlightenment, and their peaceful processes of negotiation and resolution of conflicts. It is only when a White body is killed that they see a need for human rights. These rights, I would argue, are meant more for the untouchable body [Presence] than for the Black Body [Absence].

The issue of human rights is interconnected with White supremacy, state violence, and mass incarceration of Black men and women across the globe. It is for this reason that Davis (2016:33) argues:

Racism, as it has evolved in the history of the United States, has always involved a measure of criminalization that it is not difficult to understand how stereotypical assumptions about Black people being criminals persists to this day.

Davis' argument also applies to South Africa. It can be argued that this is a form of racial profiling. It is for this reason that, according to Davis, prisons should not be viewed as separate from state violence and racism. Thus, Davis (2016:34) argues that there is a need to understand the impact of racism on institutions and on individual attitude. The National Church Leaders Forum (NCLF) (2015:5) states the following regarding the issue of mass incarceration of Black people in the United Kingdom:

The disproportionate number of BMEs in our prisons is a scandal. We urge the Government to work with BMCs and other key agencies to facilitate a national dialogue on the disproportionate representation of Black people in prison and work to reduce it.

The right to justice, which is anchored to the independence of the juridical system, is one of the rights that makes a clear distinction between the "being", the "non-being", "Subject", and "Object". As Martinot & Sexton (2010:169) rightly point out, this system denied Diallo justice and silenced Malcom Ferguson, the New York community organiser who had been tirelessly seeking justice for Diallo.

The rampant killing and police brutality of Blacks in the United States, South Africa, Britain and many other places point to the genocide of Black people by the system. Such an attempt is intentional. On the basis of the premise of "Being" and "non-being", it follows that, since non-being represents "no rights" pre-designed by the dominant ideology, non-beingness is of no value. One can draw from the above incidences and from the binary opposition between "being" and "non-being" that when a Black person carries a wallet, it is viewed as a gun, but when a White person carries a wallet, it is simply a wallet. When a Black woman has a cell phone in her hand, it is a gun; that same phone in a White woman's hand is a cell phone. When a Black body walks the streets, he is considered a drug dealer and criminal; a White body walks the streets in privilege.

In summary, since in the zone of non-being conflicts of class and gender are simultaneously articulated with racial oppression, the conflicts are managed and administered by means of violent methods and constant appropriation/some Black dispossession. Class, gender and sexual oppression, as experienced by the "Non-Being Other", is aggravated due to the joint articulation of such oppressions with racial oppression (Grosfoguel 2014: 10).

5. FREEDOM IS A CONSTANT STRUGGLE: A NEED FOR RADICAL CHRISTIAN VOICES

In this article, I have attempted to argue that there is a need to organise against police crimes, police racism, and the militarisation of the police. During apartheid, the church responded to the militarisation of police. This was expressed in the assertion made by the SACC, including the declaration by theologians and the Black church that apartheid is a heresy. One of the characteristics of Black theology of liberation has been to voice radical Christian voices. It declared blackness beautiful, thus affirming and lifting blackness from being an inferior pigmentation to being on the same level as whiteness. At the same time, it realised that whiteness is inaccessible; the struggle is not accessibility into whiteness; it is rather redefining the message in the Bible and make it relevant to the struggling masses. For this reason, freedom for Black theology of liberation was a destination. It viewed and continues to view freedom as a constant struggle. Furthermore, the radical Christian voices within Black theology of liberation were to do away with spiritual poverty of Black people.

In recent years, both Black theologians and the Black church have been silent on the continual state of violence against Black people. The Marikana massacre was supposed to have evoked the Black radical tradition of struggle that says freedom is a constant struggle.

The question regarding whose interest it is when Black lives are reduced to nothingness is essential in underpinning the motives of whiteness (Presence). I would argue that, throughout history, Black lives have not mattered, because the Subject has never seen Black people as human beings. The constructed "Master" identity through Western theology and science created a misconception that, as the "image and likeness of God", whiteness has the power to give and take life, to infuse a soul into a soulless body. In other words, whiteness has assumed that it is the "master of life".

Wilderson, III (2008: 99) makes a compelling argument regarding the Absence of Blackness:

Just as the Black body is a corpus (or corpse) of fated WHEN (when will I be arrested, when will I be shunned, when will I be a threat), the Black "homeland", and the Black "continent" on which it sits, is a map of fated WHEN battered down by toms-toms, cannibalism, intellectual deficiency, fetishism, racial defects, slave ships, and above all else, above all "Sho good eatin". From the terrestrial scale of cartography to the corporeal scale of the body, Blackness suffers through homologies of Absence.

In South Africa, the person of Sarah Baartman symbolises the extent to which the White supremacist has invaded the Black space and body. This is observed in the way in which she was exploited, paraded, penetrated, discarded, objectified, and violated as a Black woman. Through the process of pornotroping and discursive representational practices, her captive Black body was reduced into a thing to be studied. Even in death she was displayed with her genitals cut. In the eyes of the captor (whiteness), she was an animal, a missing link, using the words of Hartman (2014): a symbolic resource that provides being for the captor by way of conflation, powerlessness, objectification and sexuality.

It is essential that Black people across the globe put into question and engage with the whole narrative of the dispossessed being. It is through critical engagement with the system that prejudice continues to dispossess Blacks of their "valueless" being and to recognise a Black grammar of suffering that is an Absence in the world of Presence. Such critical discourse should necessitate a new political hegemony. Furthermore, this will not only bring about a new political hegemony; rather, it will turn Absence into Presence, while at the same time being aware that such a move is not like turning a wage labourer into a free worker. It is the reorganisation of the world.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beckles, Η. McD. 2013. Britain's Black debt: Reparations for slavery and native genocide. Jamaica, West Indies: University of West Indies. [ Links ]

Biko, S. 1987. White racism and Black Consciousness. In: S. Biko, I write what I like (Oxford: Heinemann), pp. 61-72. [ Links ]

Boesak, A. 2015. A restless Presence: Church activism and "post-apartheid", "post-racial" challenges. In: R.D. Smith, W. Ackah, A.G Reddie & R.S. Tshaka (eds), Contesting post-racialism: Conflicted churches in the United States and South Africa (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi), pp. 13-36. https://doi.org/10.14325/mississippi/9781628462005.003.0001 [ Links ]

Davis, A.Y. 2016. Freedom is a constant struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the foundations of a movement. Chicago, ILL: Haymarket Books. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 1963. The wretched of the earth. London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Gordon-Chipembere, N. 2011. Representation and Black womanhood: The legacy of Sarah Baartman. New York: Palgrace MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230339262 [ Links ]

Grosfoguel, R. 2014. Racism, intersectionality and migration studies. Summer School Lecture, College of Human Sciences, University of South Africa, 7 January. [ Links ]

Hartman, S. 2014. Human rights and the humanities. 20 March 2014, SD, National Humanities Center. [ Links ] [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z8VsTaofizk [2015, 2 February].

Kerseboom, S. 2011. Grandmother-martyr-heroine: Placing Sara Baartman in South African post-apartheid foundational mythology. Historia 56(1):63-76. [ Links ]

Lindfors, B. 2014. Early African entertainers abroad: From the Hottentot Venus to Africa's first Olympians. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. [ Links ]

Magubane, B. 2001. Social Construction of Race and Citizenship in South Africa. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development Durban, South Africa, September 3-5: 3.1-37. [ Links ]

Magubane, Ζ. 2001. Which bodies matter? Feminism, poststructuralism, race, and the curious theoretical odyssey of the "Hottentot Venus". Gender and Society 15(6):816-834. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015006003 [ Links ]

Mail & Guardian 2013. [ Links ] [Online.] Retrieved from: http://mg.co.za/article/2013-02-28-taxi-driver-killed-after-alleged-police-brutality [2015, 15 May].

Maldonado-Torres, N. 2007. On the coloniality of being. Cultural Studies 21(2):240-270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162548 [ Links ]

Martinot, S. & Sexton, J. 2010. The avant-garde of White supremacy. Social Identities: Journal of the Study of Race, Nation and Culture 9(2):169-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350463032000101542 [ Links ]

McKaiser, E. 2011. How Whites should live in this strange place. South African Journal of Philosophy 3(4):452-461. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajpem.v30i4.72106 [ Links ]

Moffat, R. 1842. Missionary labours and scenes in Southern Africa. London: J Snow. [ Links ]

Montagu, A. 1997. Man's most dangerous myth: The fallacy of race. New York: Colombia University Press. [ Links ]

Mothoagae, I.D. 2012. The stony road we tread: The challenges and contribution of Black liberation theology in post-apartheid South Africa. Missionalia 40(3):278-287. [ Links ]

________. 2014. An exercise of power as epistemic racism and privilege: The subversion of Tswana identity. Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society 16(1-2):13-14. [ Links ]

Naicker, L. 2012. The role of eugenics and religion in the construction of race in South Africa. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 38(2):209-220. [ Links ]

National Church Leaders Forum (NCLF) 2015. Black church political mobilisation: A manifesto for action. London: NCLF Publication. [ Links ]

Qureshi, S. 2004. Displaying Sara Baartman, the "Hottentot Venus". History of Science 42(2):233-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/007327530404200204 [ Links ]

Ramose, M.B. 2007. In Memoriam: Sovereignty and the "new" South Africa. Griffith Law Review 16(2):310-329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2007.10854593 [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Snyman, G. 2005. Constructing and deconstructing identities in post-apartheid South Africa: A case of hybridity versus untainted Africanicity? Old Testament and Eastern Studies 18(2):323-344. [ Links ]

Sosibo, K. 2014. [ Links ] [Online.] Available at: http://mg.co.za/article/2014-02-13-the-waterkloof-four-its-water-under-the-bridge-boys [20 February 2015].

Sutton, G. 2007. The layering of history: A brief look at eugenics, the Holocaust and scientific racism in South Africa. Yesterday and Today 1:22-30. [ Links ]

Tromp, B., Serrao, A. & Sapa 2011. Tatane was shot dead. Cape Argus, 18 April 18. [ Links ] [Online.] Available at: http://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/tatane-was-shot-dead-1.1058200#.VWlcx8-qpBc [01 March 2015].

Vice, S. 2010. How do I live in this strange place? Journal of Social Philosophy 41(3):323-342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2010.01496.x [ Links ]

Wilderson Ill, F.B. 2008. Biko and the problematic of presence. In: A. Mngxitama, A. Alexander & N.C. Gibson (eds), Biko lives! Contesting the legacies of Biko [New York: Palgrave Macmillan], pp. 95-114. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230613379_6 [ Links ]

Young, J. 1997. The re-objectification and re-commodification of Saartjie Baartman in Suzan-Lori Parks' Venus. African American Review 31(4):699-708. https://doi.org/10.2307/3042338 [ Links ]

1 Marriage registers are examples of racial markers used to categorise people.

2 Cf. also the argument by Beckles (2013).