Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.36 n.2 Bloemfontein 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v36i2.8

ARTICLES

Jeremiah 34:8-22 - A call for the enactment of distributive justice?1

Dr. M.D. Terblanche

Research Fellow, Department of Old Testament, Faculty of Theology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. mdterblanche@absamail.co.za

ABSTRACT

This article seeks to determine whether the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22, in his critique of the events relating to the manumission of Hebrew slaves in 589/588 BCE during Nebuchadnezzar's siege of Jerusalem, called for the enactment of distributive justice. Since the book of Jeremiah has a very strong intertextual character, the intertextual link between Jeremiah 34:8-22 and Deuteronomy 15:1-18 is explored. When Jeremiah 34:8-22 is read through the lens of Deuteronomy 15:1-18, it is clear that brotherliness does not tolerate debt slavery. By using Deuteronomy 15:1-18 as a supplementary text to Jeremiah 34:8-22, the author inspires visions of a counter-community, in which the debt slaves should be set free and be enabled to make a fresh start.

Keywords: Jeremiah 34:8-22, Deuteronomy 15:1-18, Intertextuality, Distributive justice

Trefwoorde: Jeremia 34:8-22, Deuteronomium 15:1-18, Intertekstualiteit, Verdelende geregtigheid

1. INTRODUCTION

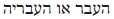

In the summary characterisation of David's reign (2 Samuel 8:15), the ideal image of the Israelite ruler is marked by the word-pair  and

and  2

2

Rendtorff (2005:646) believes that this ideal doubtless underlies the evaluations of the kings of Israel and Judah, who are compared with David.

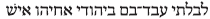

Jeremiah 22:3 admonishes the king who sits on David's throne to do what is just and right. This implied that the person who had been robbed, should be rescued from the hand of his oppressor. In 22:15, the actions of the Judean king Jehoiakim are contrasted with those of his father, Josiah. Jehoiakim had built his palace by unrighteousness and his upper rooms by injustice, in contrast to Josiah, who had practised justice and righteousness. Jehoiakim apparently used forced labour to build his house, whereas Josiah had freed the people from the corvée (Weinfeld 1995:54). Finally, 23:5-6 holds out the prospect of a new king who will re-establish justice and righteousness. The name of this king, "YHWH-Is-Our-Righteousness", seems to be a play on that of the last king of Judah, Zedekiah, "My righteousness is YHWH" (cf. Lundbom 2004:173; Allen 2008:258). In these texts, the word pair  and

and  roughly connotes what is understood as social justice.

roughly connotes what is understood as social justice.

Weinfeld (1992:237; 1995:25-31) notes that the word pair  and

and  refers to the amelioration of the situation of the destitute in some texts in the Old Testament. In his Theology of the Old Testament, Brueggemann (1997:736-738) differentiates between retributive justice and distributive justice. According to Brueggemann, distributive justice recognises that social goods and social power are unequally distributed in Israel's world and that the well-being of the community requires that social goods and power, to some extent, be given up by those who have too much, for the sake of those who do not have enough.

refers to the amelioration of the situation of the destitute in some texts in the Old Testament. In his Theology of the Old Testament, Brueggemann (1997:736-738) differentiates between retributive justice and distributive justice. According to Brueggemann, distributive justice recognises that social goods and social power are unequally distributed in Israel's world and that the well-being of the community requires that social goods and power, to some extent, be given up by those who have too much, for the sake of those who do not have enough.

According to Brueggemann's definition, distributive justice implies more than the defence of the poor and the oppressed. The intention of distributive justice is to redistribute social goods and social power (cf. Brueggemann 1997:736). Jeremiah 34:8-22 belongs to a group of texts, among which the most prominent are Exodus 21:2-11, 23:10-11; Leviticus 25; Deuteronomy 15; Ezekiel 45:7-12, 46:16-18, and Nehemiah 5, concerned with economic relief (cf. Gottwald 1997:33-34). This article explores the reflection of the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 on the events relating to the manumission of Hebrew slaves in 589/588 BCE during Nebuchadnezzar's siege of Jerusalem as a call for the enactment of distributive justice. Debt, the cause of debt slavery in Zedekiah's time, still causes immense suffering. The accusation has been made that the collection of the Third World's foreign debt is the primary tool with which the Third World development is suppressed. The structural adjustment policies that are part and parcel of that debt are meant to ensure that the debtor country will be unable to develop in a manner that would allow it to achieve a favourable insertion into the world market (cf. Bell 2001:12). This article sets out to show that Jeremiah 34:8-22 provides important perspectives on a troublesome issue in our contemporary world.

Carroll (1996:19) observes that the structure of the book of Jeremiah and its relation to other books in the Old Testament give it a very strong intertextual character. There are, for example, obvious connections between the prose sections of Jeremiah and the book of Deuteronomy. An exhaustive intertextual analysis of Jeremiah 34:8-22 would be a potentially endless process (cf. Roncace 2005:18). Since the connection between Jeremiah 34:8-22 and Deuteronomy 15:1-18 is of such a nature that Allen (2008:386) is of the opinion that Deuteronomy 15:1, 12 can be regarded as the text of the sermon in Jeremiah 34:8-22, it seems profitable to apply the concept of intertextuality to the connection between Jeremiah 34:8-22 and Deuteronomy 15:1-18. This article contends that the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 used the intertextual link with Deuteronomy 15:1-18 to call for the enactment of distributive justice.

This article begins with an examination of the intertextual link between Jeremiah 34:8-22 and Deuteronomy 15:1-18. Subsequently, it is shown that Deuteronomy 15:1-18 emphasises that brotherliness is incompatible with debt slavery. This is followed by a reading of Jeremiah 34:8-22 through the lens of Deuteronomy 15:1-18, leading to the observation that the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 does not merely criticise the conduct of the slave owners, but inspires visions of a counter-community.

2. THE INTERTEXTUAL LINK BETWEEN JEREMIAH 34:8-22 AND DEUTERONOMY 15:1-18

The occurrence in Jeremiah 34:14 of the phrase  - "at the end of seven years" - seems odd, since the second part of the verse demands that the slave had to be set free after six years of service. The latter part of Jeremiah 34:14 is in agreement with Deuteronomy 15:12, namely that the debt slave, after six years of service, should be released in the seventh year. However, the occurrence in Jeremiah 34:14a of the phrase

- "at the end of seven years" - seems odd, since the second part of the verse demands that the slave had to be set free after six years of service. The latter part of Jeremiah 34:14 is in agreement with Deuteronomy 15:12, namely that the debt slave, after six years of service, should be released in the seventh year. However, the occurrence in Jeremiah 34:14a of the phrase  makes sense when it is taken as a jump from the introductory Deuteronomy 15:1, which refers to the release of debts at the end of every seventh year, to 15:12. The text signifies that the release of debt slaves in 15:12 should be interpreted in terms of the communal debt remission in 15:1 (Allen 2008:387).3

makes sense when it is taken as a jump from the introductory Deuteronomy 15:1, which refers to the release of debts at the end of every seventh year, to 15:12. The text signifies that the release of debt slaves in 15:12 should be interpreted in terms of the communal debt remission in 15:1 (Allen 2008:387).3

Leuchter (2008:642-646) maintains that  , "at the end", in Jeremiah 34:14 should rather be regarded as a reference to Deuteronomy 31:9-11, where it is specified that the Deuteronomic law should be publicly decreed at the end of every seven years. He regards Jeremiah 34:8-22 as a Deuteronomistic attack on the Zadokites and thus the reference to the "Levitic" text, Deuteronomy 31:9-11. Leuchter does, however, concede that, taken on its own, Jeremiah 34:14a might well be read as a reference to the debt release law in Deuteronomy 15:1. It, therefore, seems more plausible to regard Jeremiah 34:14 as a conflation of Deuteronomy 15:1 and 12. The phrase

, "at the end", in Jeremiah 34:14 should rather be regarded as a reference to Deuteronomy 31:9-11, where it is specified that the Deuteronomic law should be publicly decreed at the end of every seven years. He regards Jeremiah 34:8-22 as a Deuteronomistic attack on the Zadokites and thus the reference to the "Levitic" text, Deuteronomy 31:9-11. Leuchter does, however, concede that, taken on its own, Jeremiah 34:14a might well be read as a reference to the debt release law in Deuteronomy 15:1. It, therefore, seems more plausible to regard Jeremiah 34:14 as a conflation of Deuteronomy 15:1 and 12. The phrase  , "at the end of seven years", in Jeremiah 34:12 functions as a marker, recalling Deuteronomy 15:1. The author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 hints at the fact that the passage should be read in light of Deuteronomy 15:1-18. The latter became a supplementary text to Jeremiah 34:8-22.

, "at the end of seven years", in Jeremiah 34:12 functions as a marker, recalling Deuteronomy 15:1. The author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 hints at the fact that the passage should be read in light of Deuteronomy 15:1-18. The latter became a supplementary text to Jeremiah 34:8-22.

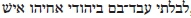

Further evidence of the intertextual link between Jeremiah 34:8-22 and Deuteronomy 15:1-18 is noted in the change in Jeremiah 34:14 from the second person plural  ("You [plural] must let go every man his brother"), to the second person singular "who may be sold to you (

("You [plural] must let go every man his brother"), to the second person singular "who may be sold to you ( )and has served you" (

)and has served you" ( ) (singular). The latter part of the verse is in the singular, because the author wanted to quote the verse as it is written in Deuteronomy 15:12 (cf. Weinfeld 1995:153).

) (singular). The latter part of the verse is in the singular, because the author wanted to quote the verse as it is written in Deuteronomy 15:12 (cf. Weinfeld 1995:153).

In both Deuteronomy 15:1-18 and Jeremiah 34:8-22, the male slaves are described with the name  , "Hebrew" (Deuteronomy 15:12; Jeremiah 34:9 (twice), 14), and the female slaves with the name

, "Hebrew" (Deuteronomy 15:12; Jeremiah 34:9 (twice), 14), and the female slaves with the name  (Deuteronomy 15:12; Jeremiah 34:9). In fact,

(Deuteronomy 15:12; Jeremiah 34:9). In fact,  only occurs in Jeremiah 34:9 and Deuteronomy 15:12. Chavel (1997:86) does, however, argue that the words

only occurs in Jeremiah 34:9 and Deuteronomy 15:12. Chavel (1997:86) does, however, argue that the words  , "or a Hebrew woman", entered the text in Deuteronomy 15:12 secondarily. According to Deuteronomy 15:17, the release law also applied to female slaves. Furthermore, it is also evident that the phrase

, "or a Hebrew woman", entered the text in Deuteronomy 15:12 secondarily. According to Deuteronomy 15:17, the release law also applied to female slaves. Furthermore, it is also evident that the phrase

does not only indicate that the debt slave might be male or female, but also that the slave was a fellow Israelite. The phrase

does not only indicate that the debt slave might be male or female, but also that the slave was a fellow Israelite. The phrase  should, therefore, be regarded as essential to the text (cf. Labuschagne 1990:88).

should, therefore, be regarded as essential to the text (cf. Labuschagne 1990:88).

Jeremiah 34:8-22 agrees with Deuteronomy 15:1-18 with regard to the slaves being called "brothers" (cf. Jer. 34:9, 14, 17). The same Hebrew verb for letting loose  is used in Jeremiah 34:14 and Deuteronomy 15:12 for letting the slaves go (cf. Allen 2008:387).

is used in Jeremiah 34:14 and Deuteronomy 15:12 for letting the slaves go (cf. Allen 2008:387).

Through the obvious allusions to Deuteronomy 15:1-18, the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 implies that it should be understood in light of the former. Jeremiah 34:8-22 is also part of other networks of texts, as will be mentioned later in this article. The close relationship between Jeremiah 34:8-22 and Deuteronomy 15:1-18 can, however, be interpreted as a "hint" that the former text should be understood in light of the latter.

Chavel (1997:72-95) attributes Jeremiah 34:8-22 to a scribe who, during or following Nehemiah's release of impoverished and enslaved Jews (Neh. 5:1-13), sought to provide Nehemiah's efforts with a Scriptural basis. Chavel regards the phrase,  "so that no one should hold a Judean, his brother, in bondage", in Jeremiah 34:9 as a conflation of words from Leviticus 25:39 and 46. It is noteworthy that Leuchter (2008:646-649) draws the opposite conclusion. He believes that the author of the Holiness Code used Jeremiah 34:8-22 in his critique of Deuteronomy's manumission law. Leuchter (2008:650) argues that the odd diction of Jeremiah 34:9 should be ascribed to internal redactional considerations rather than as an allusion to Leviticus 25.

"so that no one should hold a Judean, his brother, in bondage", in Jeremiah 34:9 as a conflation of words from Leviticus 25:39 and 46. It is noteworthy that Leuchter (2008:646-649) draws the opposite conclusion. He believes that the author of the Holiness Code used Jeremiah 34:8-22 in his critique of Deuteronomy's manumission law. Leuchter (2008:650) argues that the odd diction of Jeremiah 34:9 should be ascribed to internal redactional considerations rather than as an allusion to Leviticus 25.

Deuteronomistic phraseology is abundant in Jeremiah 34:8-22, particularly in verses 13-15 and 17 (cf. Hyatt 1984:260; Thiel 1981:38-43). Thiel (1981:103-106) proposes that Jeremiah 1-45 owes its structure to a Deuteronomistic redaction. This hypothesis was refined by Albertz (2003:312-327), who suggested three successive Deuteronomistic editions of the book Jeremiah. Albertz (2003:318-321) attributes Jeremiah 34:8-22 to the third edition, which was probably completed between 525 and 520 BCE. The object was to instruct Israel not to squander once more the great new opportunity announced by the victories of Darius over the Babylonian rebels (cf. Albertz 2003:342-343).

One can expect that a text might differ in some aspects from its intertext. Jeremiah 34:8-22 uses the term  , which can be connected to the Neo-Assyrian terminus technicus (an-)durāru. Deuteronomy, however, avoids the term

, which can be connected to the Neo-Assyrian terminus technicus (an-)durāru. Deuteronomy, however, avoids the term  , because of its connection with Neo-Assyrian practice, and rather applies the term

, because of its connection with Neo-Assyrian practice, and rather applies the term  , taken from the Covenant Code. For the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22, the Neo-Assyrian power was something of the past (cf. Otto 1999:376) and he could, therefore, apply the term

, taken from the Covenant Code. For the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22, the Neo-Assyrian power was something of the past (cf. Otto 1999:376) and he could, therefore, apply the term  with devastating effect. Since the people of Judah retrogressed from the decision to let loose their slaves, Yahweh would let loose the sword, famine and pestilence on them.

with devastating effect. Since the people of Judah retrogressed from the decision to let loose their slaves, Yahweh would let loose the sword, famine and pestilence on them.

3. DEUTERONOMY 15:1-18: BROTHERLINESS IS INCOMPATIBLE WITH DEBT SLAVERY

The idea of release is prevalent in Deuteronomy 15:1-18. Verses 1-11 pertain to the release of debts, whereas verses 12-18 call for the release of debt slaves. The juxtapositioning of these laws makes sense, since poverty and indebtedness were among the chief reasons for slavery in the Ancient Near East (cf. Hamilton 1992:30). Although Deuteronomy 15:1-18 draws upon the Covenant Code, it transforms these laws to suit the author's objectives. The motivations in Deuteronomy 15:1-18, involving the memory of slavery in Egypt and the material blessing of YHWH, seek to overcome resistance to these laws (Nelson 2002:191).

Deuteronomy 15:2-11 is built on the legal maxim in verse 1 that a release of debt should be granted at the end of every seven years (cf. Von Rad 1976:105). It is disputed whether the release is a cancellation or a deferral of debt. In Mesopotamia, the performing of mišarum is expressed by means of the idioms "to break the tablet" or "to obliterate the debt" (cf. Weinfeld 1995:167-168). The logic of Deuteronomy 15:9 favours a complete discharge of the debt (Von Rad 1976:106; Chirichigno 1993:273).

Deuteronomy 15:7-11 seeks to counter attitudes that would undermine the intention of debt remission (Nelson 2002:195). When the year for the cancelling of debts is near, the needy should nonetheless be aided. The lending of money should be done with a view to helping the debtors and not to exploiting them, to alleviating poverty and not to creating it (Sheffler 2005:110). Deuteronomy 15:1-11 expands the older tradition in the Covenant Code of letting the land lie fallow to a call for the release of debt, with the intention of countering the worst effects of the social and economic inequities that were a result of an emerging monetary economy and a breakdown in Israel's traditional communitarian ethos (Nelson 2002:190-191).

Deuteronomy 15:12 calls for the release of Hebrew debt slaves after six years of service. The law no longer relates to the purchase of a man who is not free, but to the purchase of an Israelite who has sold himself into slavery because of debt (cf. Von Rad 1976:106-107). The verb  should be taken as a reflexive. Deuteronomy 15 does not take the needs of the owner as point of departure, but that of the predicament of the person who has sold himself (cf. Braulik 1988:312; Nelson 2002:197). In addition, the slave release law in the Covenant Code is extended to apply to women slaves. The word "slave" is avoided until the point where the person himself volunteers for permanent slavery (cf. Houston 2007:186).4

should be taken as a reflexive. Deuteronomy 15 does not take the needs of the owner as point of departure, but that of the predicament of the person who has sold himself (cf. Braulik 1988:312; Nelson 2002:197). In addition, the slave release law in the Covenant Code is extended to apply to women slaves. The word "slave" is avoided until the point where the person himself volunteers for permanent slavery (cf. Houston 2007:186).4

Deuteronomy 15:1-18 is not concerned with the marginalised widow, fatherless and alien. It aims at the prevention of a permanent underclass of poor and enslaved fellow Israelites. The noun "brother" occurs six times in Deuteronomy 15:1-18.5 Already in verse 2, the word  , "his brother", clarifies the word

, "his brother", clarifies the word  , "his neighbour" (cf. Houston 2007:181). The obligation in verse 2 is to release the debt of the "brother". According to verse 12, the "brother" who became a slave as a result of debt should be released in the seventh year. It is noteworthy that, in contrast to the Covenant Code where

, "his neighbour" (cf. Houston 2007:181). The obligation in verse 2 is to release the debt of the "brother". According to verse 12, the "brother" who became a slave as a result of debt should be released in the seventh year. It is noteworthy that, in contrast to the Covenant Code where  , "Hebrew", indicates membership of a subgroup with low social status, it refers to a fellow Israelite in Deuteronomy 15. The social categories of "brother Hebrew" and "slave" are obviously understood as being incompatible (cf. Nelson 2002:190). All Judeans were brothers (cf. Otto 1999:375). For this reason, Deuteronomy avoids the term

, "Hebrew", indicates membership of a subgroup with low social status, it refers to a fellow Israelite in Deuteronomy 15. The social categories of "brother Hebrew" and "slave" are obviously understood as being incompatible (cf. Nelson 2002:190). All Judeans were brothers (cf. Otto 1999:375). For this reason, Deuteronomy avoids the term  , "master", which occurs repeatedly in Exodus 21:2-6 (cf. Nelson 2002:198). Although the institution of debt-bondage is not abolished, Deuteronomy 15:12-18 suggests that there cannot be masters and slaves within a family of brothers (Houston 2007:187). Brotherliness is incompatible with debt slavery.

, "master", which occurs repeatedly in Exodus 21:2-6 (cf. Nelson 2002:198). Although the institution of debt-bondage is not abolished, Deuteronomy 15:12-18 suggests that there cannot be masters and slaves within a family of brothers (Houston 2007:187). Brotherliness is incompatible with debt slavery.

It is significant that, while the law in the Covenant Code only calls for the release of the slave, Deuteronomy 15:12-18 requires the master to provide generously for the impoverished person on releasing him/her (McConville 2002:263). The provision of animals from the master's flock would help the former debt slave start anew (cf. Chirichigno 1993: 279).

4. THE DEPICTION OF THE MANUMISSION OF THE HEBREW SLAVES DURING ZEDEKIAH'S REIGN IN JEREMIAH 34:8-22 READ THROUGH THE LENS OF DEUTERONOMY 15:1-18

Jeremiah 34:8-22 consists of a report on the events relating to the manumission of the Hebrew slaves (verses 8-11) and four divine oracles (verses 12-22) (cf. Lundbom 2004:556). Jeremiah is not commanded to direct the oracles in 34:8-22 to anyone specific. The direct address ("you") in verses 13-17 (verses 18-22 are in the third person) implies that they were meant to be spoken to the people (cf. Fretheim 2002:487). While societal justice had everything to do with the king (cf. Lundbom 1999:295), the blame is not placed on Zedekiah alone. The first divine oracle (verses 12-16) starts with a reference to the covenant made at the time of the exodus, which the ancestors had disobeyed by not acting in accordance with the laws attested in Deuteronomy 15:1, 12. The divine oracle concludes with the indictment that the people of Jerusalem had acted in the same way by pressuring their erstwhile slaves back into their service.

The release during Zedekiah's reign was a general release for all Hebrew slaves. This corresponds to releases known to have occurred throughout the Ancient Near East (Lundbom 2004:559). The number of years of service of each individual slave was not taken into consideration (cf. Weinfeld 1995:153). Various attempts were made to relate Zedekiah's proclamation to a sabbatical year (cf. Sarna 1973:147-149; Lundbom 2004:561). However, the conduct of the former slave owners, following the withdrawal of the Babylonian army from Jerusalem, implies that the release of the slaves was self-serving. If the slaves were set free, they could be drafted into the army. If the slaves were set free, they would in time of siege and food scarcity have to find food and shelter on their own (cf. Lundbom 2004:559). Zedekiah's royal proclamation was in all likelihood dependent on the Neo-Assyrian royal practice (cf. Lemche 1976:56-57).

The author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 did not only have knowledge of Deuteronomy 15:1-18, but also expected that the readers would be able to identify the alluded text (cf. Edenburg 2010:147). He interprets the retrogressing by the slave owners on their decision to free their debt slaves as a contravention of the covenant made with YHWH. The author viewed the release of the slaves as the implementation of Deuteronomy 15:1-18. The slave owners acted contrary to the spirit of Deuteronomy 15:1-18 when they reneged and pressurised their erstwhile slaves back into their service. Deuteronomy 15:16-17, 18a stipulates that only the slave could negate the intention of the release law by choosing to remain permanently in service of his owner. Instead of pressurising their erstwhile slaves back into their service, the slave owners should have enabled the released slaves to make a fresh start (cf. Braulik 1988:313; Hamilton 1992:81).

By alluding to Deuteronomy 15:1-18, where the law concerning the manumission of a slave is juxtaposed to the law on the remission of debts, the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 calls for the end of the practice of debt slavery. For the same reason, he pairs  with

with  (cf. Jer. 34:9, 14), as is done in Deuteronomy 15:1-18. The Hebrew slaves and the slave owners were brothers. It is interesting to note that Zedekiah is portrayed, in Jeremiah 34:9, as conceding that the debt slaves were the brothers of their owners by the use of the phrase

(cf. Jer. 34:9, 14), as is done in Deuteronomy 15:1-18. The Hebrew slaves and the slave owners were brothers. It is interesting to note that Zedekiah is portrayed, in Jeremiah 34:9, as conceding that the debt slaves were the brothers of their owners by the use of the phrase  , "so that no one should hold a Judean, his brother, in bondage". Brotherliness does not tolerate debt slavery, as suggested by Deuteronomy 15:1-18.

, "so that no one should hold a Judean, his brother, in bondage". Brotherliness does not tolerate debt slavery, as suggested by Deuteronomy 15:1-18.

5. A VISION OF AN ALTERNATIVE COMMUNITY

The immediate context of the account dealing with the manumission of slaves in Zedekiah's reign in Jeremiah 34:8-22 suggests that the conduct of the slave owners is an example of unfaithfulness. Jeremiah 34:8-22 is juxtaposed to the account concerning the Rechabites (35:1-19), who were an example of faithfulness (cf. Lundbom 2004:105-110). While the Rechabites were obedient to the commands of their forefather Jonadab, the slave owners in Jerusalem violated the terms of the covenant that set the debt slaves free. Considering the wider context, Jeremiah 26-52, it is important to take Stulman's observation with regard to these chapters into consideration. Stulman (1998:97) argues that the fundamental claim of Jeremiah 26-52 is that the God that destroys is the very God who builds (45:4). Israel's "worst news" provides the very context and experience for the emergence of hope and "good news". Furthermore, Jeremiah 30-33, the chapters that precede the chapter dealing with the manumission of debt slaves, announces "good news". The "bad news" announcing that the Babylonian army would return to Jerusalem and conquer the city, should, therefore, be read against the "good news" of the restoration of Judah's fortunes, as is, for example, announced in Jeremiah 32:42-44.

There seems to be an intertextual connection between Jeremiah 34:8-22 and 31:31-34. In 34:12-16, the slave owners' action of pressurising their erstwhile slaves back into their service is placed on the same level as the violation of the covenant made with the ancestors at the time of the exodus. However, in 31:31-32, the covenant made with the ancestors is contrasted with a new covenant that YHWH will establish with Israel and Judah in the future. Albertz (2003:344) suggests that the expectations that YHWH would put his law in the people's minds and write it on their hearts (31:33) are clearly utopian. It implies that the author's work of theological instruction would soon be superfluous, because people would no longer teach each other, because all would know YHWH (31:34). O'Conner (2006:89) characterises the whole of Jeremiah 30-31 as Jeremiah's utopian future. O'Conner (2006:94) does, however, emphasise that only the God of the ancestors can bring the promised, incandescent future into life. The intertextual link between 34:8-22 and the utopian text 31:31-34 bolsters the critique of the slave owners' action of pressurising their erstwhile slaves back into their service. In the future, when YHWH will establish a new covenant, debt slavery would no longer be practised.

The book of Deuteronomy articulates a vision of an ideal community (cf. Vogt 2008:41).6 Deuteronomy 15:4, which can be taken as a command that there should be no poor in Israel (cf. McConville 2002:259), is a clear example. As Sheffler (2005:103) remarks, the endeavour to eradicate poverty should be embarked on, irrespective of the potential success. As noted earlier, Deuteronomy 15:1-18 became a supplementary text to Jeremiah 34:8-22. From this perspective, the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 does not merely criticise the conduct of the slave owners. He inspires visions of a counter-community. The cycle of dependence should be broken by enabling the former debt slaves to make a fresh start.

Weinfeld (1995:168-169) notes that Nehemiah gave expression to the idea of Jeremiah 34 that a Jew should no longer press claims against his brother (cf. Neh. 5:9-10). Nehemiah made the remission of debts an abiding principle. He ordered the manumission of men and their children who were enslaved on account of debt. Mortgaged fields and vineyards also had to be returned.

6. JEREMIAH 34:8-22: A CALL FOR THE PRACTICE OF DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE?

Distributive justice is inherently destabilising the status quo (Brueggemann 1997:738). The retrogressing by the slave owners on their decision to free their debt slaves can be regarded as an attempt to restore the status quo. Their established interests have been placed in jeopardy by the manumission of the debt slaves. However, in his critique of the events relating to the manumission of slaves during Zedekiah's reign, the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 offers a new vision of the future. In accordance with Deuteronomy 15:1-18, debt slaves should be freed and enabled to make a fresh start. To use Brueggemann's (1997:736-738) definition of distributive justice, social goods and power had to be given up, to some extent, by those who had too much, for the sake of those who did not have enough. It can, however, not be said that this had to be done for the sake of the well-being of the community or, to use a modern phrase, for the sake of the "common good". YHWH is the sole legal authority behind the call for the release of the Hebrew debt slaves (cf. Chavel 1997:85). The command to care for the needy came from God, not from the "city hall" (cf. Birch et al. 2005:158). It should be heeded whatever the cost of its implementation might be. The cycle of dependence should be broken and those in debt enabled to make a fresh start.

7. CONCLUSION

Zedekiah issued a royal proclamation of the emancipation for male and female Hebrew slaves. It was put into effect through a solemn covenant contracted in the temple (cf. Jer. 34:5-10, 15, 18-19). However, when the entry of an Egyptian relief force into Judah resulted in the withdrawal of the Babylonian army from Jerusalem, the slave owners reconsidered their decision and pressurised their erstwhile slaves back into their service (cf. Sarna 1973:144). The author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 is severe in his criticism of the conduct of the slave owners. Because they had taken back the slaves they had set free and acted contrary to the law regarding the freeing of debt slaves, the slave owners would fall by the sword, plague and famine. Even king Zedekiah would not be spared (34:17-22).

The author nonetheless inspires visions of a counter-community through the intertextual links with Deuteronomy 15:1-18 and Jeremiah 31:31-34. Like their ancestors, the slave owners did not listen to YHWH. According to Jeremiah 31:31-32, however, YHWH will establish a new covenant with Israel and Judah in the future. Through the link with Deuteronomy 15:1-18, the author of Jeremiah 34:8-22 calls for the end of the practice of debt slavery. The cycle of dependence should be broken by enabling the former debt slaves to make a fresh start. Jeremiah 34:8-22 can, therefore, be regarded as a call for the enactment of the concept of distributive justice.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albertz, R. 2003. Israel in exile. The history and literature of the six century B.C.E. Transl. by D. Green. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [ Links ]

Allen, L.C. 2008. Jeremiah. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. Old Testament Library. [ Links ]

Bell, D.M., Jr. 2001. Liberation theology after the end of history. A refusal to cease suffering. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Birch, B.C., Brueggemann, W., Fretheim, T.E. & Peterson, D.L. 2005. A theological introduction to the Old Testament. 2nd edition. Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Braulik, G. 1988. Das Deuteronomium und die Menschenrechte. In: Studien zur Theologie des Deuteronomiums (Stuttgart: Verlag Katholisches Bibelwerk, Stuttgarter Biblische Aufsatzbände 2), pp. 301-323. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 1997. Theology of the Old Testament. Testimony, dispute, advocacy. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Carroll, R.P. 1996. Jeremiah, intertextuality and ideologiekritik. JNWSL 22:15-34. [ Links ]

Chavel, S. 1997. "Let my people go!" Emanicipation, revelation and scribal activity in Jeremiah 34:8-11. JSOT 76:72-95. [ Links ]

Chirichigno, G.C. 1993. Debt-slavery in Israel and the Ancient Near East. Sheffield: JSOT Press. JSOTSS 141. [ Links ]

Edenburg, C. 2010. Intertextuality, literary competence and the question of readership: Some preliminary observations. JSOT 35:131-148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309089210387228 [ Links ]

Fretheim, T.E. 2002. Jeremiah. Macon, Georgia: Smith & Helwys. Smuyth & Helwys Bible Commentary. [ Links ]

Gottwald, N.K. 1997. The Biblical jubilee: In whose interests? Jewish and Christian insights. In: H. Ucko (ed.) The Jubilee challenge: Utopia or possibility? (Geneva: WCC Publications). [ Links ]

Hamilton, J.M. 1992. Social justice and Deuteronomy. The case of Deuteronomy 15. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature. [ Links ]

Houston, W.J. 2007. Contending for justice. Ideologies and theologies of social justice in the Old Testament. London: T. & T. Clark. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 428. [ Links ]

Hyatt, J. P. 1984. Jeremiah and Deuteronomy. In: L.G. Perdue & B.W. Kovacs (eds) A prophet to the nations. Essays in Jeremiah studies (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns), pp. 113-127. [ Links ]

Labuschagne, C.J. 1990. Deuteronomium. Deel II. Nijkerk: Callenbach. POT. [ Links ]

Lemche, N.P. 1976. The manumission of slaves - the fallow year - the sabbatical year - the jobel year. VT 26:38-59. https://doi.org/10.2307/1517108 [ Links ]

Leuchter, M. 2008. The manumission laws in Leviticus and Deuteronomy: The Jeremiah connection. JBL 127:635-653. https://doi.org/10.2307/25610147 [ Links ]

Lundbom, J.R. 1999. Jeremiah 1-20. A new translation with introduction and commentary. New York: Doubleday. Anchor Bible 21A. [ Links ]

_______. 2004. Jeremiah 21-36. A new translation with introduction and commentary. New York: Doubleday. Anchor Bible 21B. [ Links ]

McConville, J.G. 2002. Deuteronomy. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic. Apollos Old Testament Commentary. [ Links ]

Nelson, R.D. 2002. Deuteronomy. A commentary. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox. Old Testament Library. [ Links ]

O'Conner, K.M. 2006. Jeremiah's two visions of the future. In: E. Ben Zvi (ed.), Topia and dystopia in Prophetic literature (Helsinki: Finnish Theological Society. Publications of the Finnish Exegetical Society 92), pp. 86-104. [ Links ]

Otto, E. 1999. Das Deuteronomium. Politische Theologie und Rechtsreform in Juda und Assyrien. Berlin: De Gruyter. BZAW 284. [ Links ]

Rendtorff, R 2005. The canonical Hebrew Bible. A theology of the Old Testament. Transl. by D.E. Orton. Leiden: Deo Publishing. [ Links ]

Roncace, M. 2005. Jeremiah, Zedekiah, and the fall of Jerusalem. New York: T. & T. Clark. JSOTSS 423. [ Links ]

Sarna, N. 1973. Zedekiah's emancipation of slaves and the sabbatical year. In: H.A. Hoffner, jr. (ed.) Orient and occident. Essays presented to Cyrus H. Gordon on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday (Kevelaer: Verlag Butzen & Bercher. AOAT 22), pp.143-149. [ Links ]

Saur, M. 2004. Die Königpsalmen. Studien zur Entstehung und Theologie. Berlin: De Gruyter. BZAW 340. [ Links ]

Sheffler, E. 2005. Deuteronomy 15:1-18 and poverty in (South) Africa. In: E. Otto & J. le Roux (eds.) A critical study of the Pentateuch. An encounter between Europe and Africa (Münster: Lit Verlag. Altes Testament und Moderne 20), pp. 97-115. [ Links ]

Stulman, L. 1998. Order amid chaos. Jeremiah as symbolic tapestry. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Thiel, W. 1981. Das deuteronomistiche Redaktion von Jeremia 26-45. Met einer Gesamt-beuteilung der deuteronomistichen Redaktion des Buches Jeremia. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag. WMANT 52. [ Links ]

Vogt, P.T. 2008. Social justice and the vision of Deuteronomy. JETS 51(1):35-44. [ Links ]

Von Rad, G. 1976. Deuteronomy. A commentary. Transl. by D. Barton. London: SCM Press. Old Testament Library. [ Links ]

Weinfeld, M. 1992. "Justice and righteousness" - the expression ופט וצדקה and its meaning. In: H.G. Reventlow & Y. Hoffman (eds) Justice and righteousness. Biblical themes and their influence (Sheffield: JSOT Press. JSOTSS 137), pp. 228-246. [ Links ]

_______. 1995. Social justice in ancient Israel and in the Ancient Near East. Jerusalem: Magness Press. Publications of the Perry Foundation for Biblical Research at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. [ Links ]

1 Paper presented at a conference on Re-thinking justice and righteousness in society. Faculty of Theology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, 24 August 2015.

2 Cf. also Psalm 72, which has the king as defender of the poor and the oppressed as its leading theme (cf. Houston 2007:138-141). It is interesting to note that Saur (2004:135) assigns Psalm 72:1aB*.b-7, 12-14 to the time of Josiah.

3 The reading in the Septuagint "six years" seems to be a deliberate change by the translator. Cf. Lundbom (2004:563).

4 Cf. Deuteronomy 15:16.

5 In Deuteronomy 15:2, 3, 7, 9, 11, 12.

6 According to Otto (1999:364), the Deuteronomic reform programme was meant to be an alternative to the Neo-Assyrian challenge.