Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.36 supl.23 Bloemfontein 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v23i1s.9

The reception of the Deuteronomic social law in the Primitive Church of Jerusalem according to the Book of Acts

A. Friedl

Deputy Head of the Library of Theology at the University Library of Vienna; Lecturer in New Testament Greek at the University of Vienna, and Research Fellow, Department of New Testament, Faculty of Theology, University of the Free State. E-mail: alfred.friedl@univie.ac.at

ABSTRACT

The Book of Deuteronomy was extant in the Jewish cultural memory and played an important role in shaping Jewish identity. Its concept of the holy people of God, who live according to the social order given by YHWH and who stand in contrast to the pagan world, forms the social model for the Primitive Church in Jerusalem. Since New Testament exegesis has, to a large extent, neglected the role of this book of the Torah in understanding the Primitive Church, this study investigates the reception of Deuteronomy's social law in Acts 2:42-47, 4:32-35, and 6:1-7, in terms of its theological or ecclesiological importance.

Keywords: Deuteronomy, Social law, Acts, Primitive Church: Jerusalem

Trefwoorde: Deuteronomium, Sosiale wet, Handelinge, Vroeë Kerk: Jerusalem

1. INTRODUCTION

Plato and Aristotle or the Hebrew Bible? Were members of the Primitive Church in Jerusalem, which mainly consisted of Jews from Galilee and Judea, more familiar with Greek philosophy than with those Biblical texts about which they talked at home or on the road, when they lay or woke up, saw on hands, foreheads, doorframes and gates (cf. Deut. 6:7-9)? Since Biblical scholars started to acknowledge Luke's appeal to Graeco-Roman friendship traditions in Acts 2 and 4 in the mid-eighteenth century,1 they have, to a large extent, been neglecting the Biblical background of the evangelist's characterisation2 of the primitive Jerusalem community. Therefore, in order to become aware again of this fundamental dimension of the Primitive Church's social and ecclesiological (self-)understanding, this study highlights the importance of the Deuteronomic social law3 for the early Jerusalem community. As a presupposition for an adequate interpretation of Acts 2:42-47, Acts 4:32-35 and Acts 6:1-7, the study describes the hermeneutic aspects regarding the use of Deuteronomy in Acts. This is followed by an outline of the social utopias of Deuteronomy and Acts and of the theology of Deuteronomy.

2. HERMENEUTIC ASPECTS REGARDING THE USE OF DEUTERONOMY IN ACTS

The Deuteronomic people of God form the model for the characterisation of the Primitive Church of Jerusalem in Acts, in that the programme of the Deuteronomic counter-societal project of a society without any poor is being realised, and festival joy emanates from the brotherly meal (Braulik (2012a:187).4 As a collection of speeches held by Moses, the Book of Deuteronomy claims to be his last will, namely the definite proclamation of YHWH's will for his people, Israel (Braulik 2012a:165). And pretending to have been written by Moses as well, the Book of Deuteronomy presents itself overall as a basic Jewish document that was extant in the public or cultural memory. The book "played a significant role in creatively shaping Jewish identity" in such a way that basic "identity-shaping texts and ideas were taken over [...] and were popular in ancient Jewish texts" (Labahn 2007:82). It is not only frequently used in ancient Jewish literary documents, but it is also - along with the Psalms and Isaiah - the most widely used Old Testament book that is quoted, alluded or referred to in the New Testament (Labahn 2007:82).5

a. The widespread knowledge of the book of Deuteronomy is the reason "why ancient Jewish writings allude to Deuteronomic conceptions, ideas and motifs without necessarily referring back to the book of Deuteronomy as a written source" (Labahn 2007:82; see also 95, 97-98). This implies that "allusions, echoes, motifs and texts illustrating the Biblical background, such as Jewish customs and feasts" (Labahn 2007:83) in the New Testament, which apparently originated in Deuteronomy, may have their "roots in the history of reception of the book in the public memory" (Labahn 2007:82) and not necessarily in the book itself, because it was so well known to the intended or implied readers (Labahn 2007:83). Therefore, it would be misleading to follow the maxim of verbal identity for correct quotations and, because of that, to exclude the "creative reception" of a text in an (un)marked citation "purely on the basis of insufficient verbal identity" (Labahn 2007:85).6

b. Christian authors "typically cite and allude to selected passages" (Lim 2007:8).

c. When certain the New Testament texts were read, it was inevitable that those who heard them associated them with well-known Old Testament texts, thus giving the texts they heard their actual meaning (Berger 1977:95-96). Although reception depended, to a high degree, on the level of knowledge of the audience, there may have been the possibility of associative reception (Berger 1977:96).7

d. Since, in its early phase, the developing Church was part of the Jewish people and the Torah and its economic law had the same status in the developing Church, the Torah also had unlimited legal force for the first Christians (Kessler 2009a:29). The fact that certain regulations are not explicitly mentioned does not imply that they were not in force for Christians; on the contrary, they may simply have been taken for granted and were thus obeyed, so that it was unnecessary to repeat them (Kessler 2009a:29).

3. DEUTERONOMY AND ITS USE IN ACTS

Luke's explicit quotations of Deuteronomy, which are very likely originally derived from the LXX (Rusam 2007:65),8 show a fundamental difference in their use in his Gospel and in Acts (cf. Rusam 2007:81).

a. Those texts, which Luke had found in the tradition (Mark or Q) (Rusam 2007:63-75, 81) and used in his Gospel, are of a paraenetic (or normative) character (imperative, prohibitive, command) and are mainly taken from the paraenetic section, Deut. 5-11 (Braulik 2012a:166).

b. In contrast to the use in the third Gospel, the citations in Acts 3:22 and 7:37 have a prophetic character and are taken from the Law of the Prophets (Deut. 18:9-22). The basis for applying this law to Jesus is to be found in Luke 18:31-33 and 24:44-47. Despite the continuity between Peter and Stephen, when quoting Deuteronomy 18:15 in nearly the exact word order, the citation has a different function (Rusam 2007:78, 80-81).9

i. In Acts 3:22-23, it forms the basis for the necessity of Peter's call of repentance, which had been prophesied by God's prophets and had to be fulfilled by Jesus' followers. This prophetic Christology (Bruce 1990:145) describes Jesus as a liberating prophet.

ii. In Acts 7:37, it is used typologically to show that both Moses and Jesus shared the same fate, namely being rejected by the Israelites or the Jews.

4. THE SOCIAL UTOPIAS OF DEUTERONOMY AND ACTS

Both Deuteronomy and Acts show certain social utopian10 elements. The topic of a social utopia,11in sensu stricto, is a fictitious better social order or better circumstances of life that are presented in local or temporal distance and that claim to be "realistic" or "anticipated reality" (Bichler 2008:11, 15 n. 22). In the Greek and Hellenistic world, retrospective utopian conceptions value social reality. They are primarily a specific reaction to social changes that by looking back, express their dissatisfaction with the present time by projecting a better world (Bichler 2008:11-13, 16, 20). By constituting a contrast to times of fundamental change, crises and grievances such as poverty and suppression, social criticism is inherent to them to a high degree (Bichler 2008:20, 24-25; Uhlenbruch 2015:39-44). Their social critical component is fixed to an idealised unspoilt past or early period when easy life dominated. This, in particular according to Hellenistic-Roman texts, partly included the relinquishment of personal property (Bichler 2008:16-18). Notwithstanding their progressive ethical intent and their striving towards well-ordered and clear circumstances, the programmatic-innovative potential or power of utopian conceptions to reform society reached their limits when they became economically, socially and politically backward.12 Since the complexity of the Hellenistic society restricted the political action of the individual, the economic and social primitiveness of utopian life marks the reaction to the actual circumstances that were at variance with the ideals of life (Bichler 2008:2). Thus, the social desire inherent to the utopian social conceptions, as indicators and not factors of social changes, is directed to the past, not to the future (Bichler 2008:11, 20, 23-24).

Whereas classical Greek and Hellenistic-Roman utopian writings and narratives about Eden/Paradise, at the beginning of the Bible, and the apocalyptic visions, at the end of the Bible, imagine places out of this world, the just counter-society without any poor of Deuteronomy and Acts belongs to those Biblical writings that envision the model of an ideal community.13 Although, during the Second Temple period, the greater part of the Jewish people lived in geographically remote diasporas (Mesopotamia, North Africa, Asia Minor, Italy), there are no diasporic utopian visions of an ideal Jewish community beyond the land of Israel, at least not prior to Philo (Collins 2000:58-59, 64-65).

However, there is a fundamental difference between the use of the genre "social utopia" in classical Greek and Hellenistic-Roman literature, on the one hand, and in Deuteronomy, on the other. Whereas it is embedded into fiction in the former, Deuteronomy promulgates its new societal model as law that finally turns into paraenesis in combination with the conviction that this society, which seems to be impossible, can be turned into reality by an appropriate behaviour of Israel - the observance of the Torah (Lohfink 1996:17; Collins 2000:53).

In this respect, Acts follows the same trajectories as Deuteronomy - the Primitive Church of Jerusalem realises the new counter-society. Contrary to the Greek and Hellenistic-Roman concepts, Acts directs its social desire as an implicit paraenesis aimed towards the future by referring to the past. The indicated social change is the conversion to Christianity, presented in the form of an ideal people in nuce that YHWH has had in mind from the very beginning. This ideal ecclesiological image of the ecclesia primitiva is compelling and stimulating (Pesch 2005:132). The Messianic community in Jerusalem is the archetypical prototype of the eschatological community of salvation at the time of commencement of the Church (Marguerat 2011:69 n. 39, 163, 250; Klein 2015:3, 5-6, 13, 15). This Church is not an idealising nostalgic ideal, but the ecclesiological-pneumatological concept of a normative prototype that is intended to encourage believers (Marguerat 2011:69 n. 39; Klein 2015:6, 33-34).

5. THE THEOLOGY OF DEUTERONOMY14

Deuteronomy reflects on vital theological themes and is one of the first extensive theological syntheses in Israel. It draws up a societal blueprint of Israel15 within which all areas of life are embedded into the relationship with YHWH and where real life is part of that which is sacred. The book drafts the theology of the people of God par excellence by systematising "the theory for the social centre of a 'civilisation of love'" (Braulik 2012a:182), mainly in terms of three aspects.

a. Deuteronomy regards itself as compendium of the Torah of YHWH and turns Israel into a community of learning faith (Braulik 2012a:183; 2012b:550, 552). In order to socialise Israel to the people of YHWH by transmitting all matters of faith within the family and in the assembly at the central sanctuary, the book outlines a new kind of collective mnemotechnics: for example, the educational method of repetition for learning the omnipresent law (see, for example, Deut. 6:6-9; 11,18-21); short formulas of faith for special situations;16 the Decalogue (Deut. 5:6-22) as ethical short formula, and at the Feast of Booths (Deut 31:10-13), the public ritual of learning by listening to and repeating the Torah.

b. Feast and celebration are the clearest modes of self-portrayal of Israel's society arising from the Word of God (Braulik 2012a:183-184).

i. Feast. According to the festival theory of Deuteronomy (Braulik 2012a: 183; 2012b:550), the pilgrimage festivals are the primary places where the world of Israel is interpreted and the people are socialised. The mystic dimension of the feast's liturgy is linked to the communal festal meal where Israel experiences the realisation of the concept of being YHWH's people: the families' communal prayers and meals during their sacrifices (see, for example Deut. 12) and offerings (see, for example Deut. 14:22-27) or celebration of the Feasts of Weeks (Deut. 16:9-12) and Booths (Deut. 16:13-15) lead to absolute joy before YHWH. All Israel's being together without any social differences makes a brotherly society come true in a realistic symbolic way where women are allowed to offer sacrifices and where there are no poor (Braulik 1999:passim).

ii. Celebration. The celebration of Passover as commemoration of passion (Braulik 1994b:71-76; 2012a:183-184) recalls, in the communal sacrificial meal, the affliction of Israel's Exodus. Eating the unleavened bread turns Israel, already living in the Promised Land, into the people of the Exodus again. Remembering "the day of your going out from the land of Egypt all the days of your life" (Deut. 16:3*) changes the social consciousness of the people of Israel.

c. The liturgical reform entails a fundamental and complete social reform (Lohfink 1996:12-13, 15-16; Braulik 2012a:184). The ideal of brotherliness,17 the development of which is unparalleled in the Old Testament, refers to the pre-monarchic egalitarian tribal society and overcomes class society. It motivates the Deuteronomic social legislation that provides against poverty (Deut. 15:4-6, 11) and the miscellaneous humanitarian regulations in Deuteronomy 15* and 19-25. It merges various traditions, unifies them and constructs a thoroughly calculated legal system in order to ensure that, at various occasions, those social groups that did not own landed property received their lawful share (Lohfink 1996:12-13). In its project of a counter-society, this change of social structures not only included simply meeting material needs, but also provisions to ensure an equivalent share in Israel's joy, especially the joy of the feasts. By eliminating the differences in status, Deuteronomy creates an egalitarian society in which those groups that, for different reasons, were not able to live independently or off their own land, were no longer deemed to be needy or poor: "The non-existence of any poor is an indispensable constituent element for Israel. Poverty does not belong to the realities which are projected for this 'world'" (Lohfink 1996:14).

The שמע (Deut. 6:4-9, which speaks of YHWH's oneness and Israel's duty to love him as a society) is the central core of this kind of brotherly love that transcends any law and encompasses all Israel, in particular, and of the Deuteronomic legal paraenesis, in general: Israel's corporate love gives rise to a social structure with a brotherly pattern (Lohfink 1996:15; Braulik 2012a:184, 187-188; 2012b:552-553, 557). Israel, YHWH's family, loves its God freely and joyfully by realising her social regulations, namely the Deuteronomic law. Only this social love creates brotherly structures and eliminates powers and classes.

In addition to these three aspects, there are other theological issues that are relevant to the passages of Acts under discussion:

(i) Israel's sacrificial worship is exclusively centralised at the Temple in Jerusalem (cf. Deut. 12), where the three pilgrimage festivals (cf. Deut. 16:1-17) were celebrated (Lohfink 1996:5-6).

(ii) On account of the Torah, Israel stands out significantly among all other nations. The utopian project of a just counter-society presented in the Book of Deuteronomy is meant solely for YHWH's people (Lohfink 1996:5-6, 15). He is present at her boundaries where poverty threatens to enter when the poor cry out to, or call upon YHWH (cf. Deut. 15:9; 24:15) - whoever does not combat poverty in the context of the process of indebtedness, commits חטא (sin) (Lohfink 1996:15-16, 18). Due to the constitutive part played by the economic and socially poor concerning sin and righteousness of the free Israelite, the Book of Deuteronomy employs the theological dignity of the poor in the paraenesis of its law, which is directed towards the free Israelite (Kessler 2009d:265).

6. SUMMARY PASSAGES OF ACTS

The Deuteronomic social law18 refers to mainly the two large summary passages19 (Acts 2:42-47; 4:32-35) that retrospectively portray the interior life of the earliest stage of the Jerusalem Church at its best. From a narrative point of view, these summaries serve as bridging passages; the use of source material is rather typical of ancient historiographies that were based on research and the use of sources (Witherington 1998:158-159).

6.1 Acts 2:42-47

This passage addresses the liturgical life and the sharing of possessions of the growing Primitive Church in Jerusalem that obviously consisted of the twelve Apostles, the women, Mary the mother of Jesus, the approximately one hundred and twenty brethren (cf. Acts 1:13-26) as well as the approximately three thousand men of Judea and all who dwell in Jerusalem (cf. Acts 2:14, 41) - all of them being Jews without exception. The emphasis on Jerusalem and its exclusively Jewish agents leads to the question as to whether the occurrence of two words, namely απαντα κοινά in verse 44, justifies the practice of Biblical scholars to characterise the Primitive Church as an ideal community of friends according to the ideal of Graeco-Roman friendship.20

According to verse 43b, "many portents (τέρατα) and signs (σημεία) were taking place through the apostles" (cf. also Acts 4:30; 5:12; 6:8). This expression has its origin in the Deuteronomic phrase אתות ומופתים (signs and portents; LXX: σημεία καί τέρατα), which is rooted in the tradition of the Egyptian plagues and summarises all the events that took place in Egypt prior to the Exodus.21 By combining two words in a way that is typical of Deuteronomy, אתות stands for some Egyptian plagues and especially for those deeds whereby Moses has borne witness of himself to the Israelites, and מופתים refers to all plagues.22 Furthermore, אתות implies a situation at court where obvious evidence has to be offered in order to substantiate an allegation, or an ordeal that is being announced and then comes true (Braulik 1979:76).

In the context of the oldest creed (Deut. 26:5-9), the phrase in Deuteronomy 26:8 emphasises that the legitimacy of the Exodus has been clearly proven for the entire world (Braulik 1979:76; 1992:194). By using these two keywords, Luke recalls both the liberation of Israel to the new counter-society by YHWH through Moses who is replaced now, in this new liberation, by the apostles, and its legitimate evidence and clarity. The metathesis23 of the words (cf. also Acts 6:8) is theologically caused by the specific legal connotation of אתות with reference to Acts 2:22 (cf. also Pesch 2005:121, 131): the activity of the apostles corresponds to that of Jesus the Nazarene who has been attested to the men of Israel by YHWH - the legal proof of evidence or truth of their activity.

Verse 46 depicts the daily liturgy of members of the Primitive Church that considers herself to be the true Israel (cf. already Schmitt 1953:213-217) leading a life full of joy (έν αγαλλιάσει) (Braulik 1994b:64-65). This festal joy originates in the Christ event, and "that is why it immeasurably exceeds that festal joy which Deuteronomy demanded of Israel" (Braulik 1994b:65) in the stipulation of Deuteronomy 16:10-12. The verb שמח constitutes the keyword of the Deuteronomic festival theory, describing human behaviour as an expression of a religious attitude, the Israelite cult being the authentic place for this joy (Braulik 1994b:38, 40).

Verses 47b and 6:7a speak of the growth of the Primitive Church as a result of the Lord's action. According to Deuteronomy 15:4b, 6, 10, the obedience of Israel to YHWH's law/social order, i.e. Israel's solidarity with the poor (Braulik 2000:112), will result in His blessing and in prosperity.

6.2 Acts 4:32-35

Acts 4:31-5:16 reports on the effects of the second outpouring of the Holy Spirit over all servants (cf. Acts 4:29, 31) in Jerusalem as a response to their prayer for boldness (cf. Heb. 4:29) addressed to God, the Lord and creator (cf. Acts 4:24) (Keener 2013:1173-1204). Thus, Pentecost is "not only a past event but also a model for the praying church" (Keener 2013:1173).

By recalling Old Testament theophanies, verse 31 narrates the dramatic confirmation that the community's prayer is answered (Keener 2013:1173-1175). Accompanied by striking physical phenomena, those who were praying are filled with the Holy Spirit, "God's continuing, dynamically active power among God's people" (Keener 2013:1175). By paralleling this passage to Acts 2:42-47, Luke illustrates through the experience of the day of Pentecost that outpourings of the Holy Spirit in response to prayer lead to a community of sharing and to continued Apostolic prayer (Keener 2013:1175).

As a rule, exegetes interpret verse 32 in terms of the ideal of friendship as developed by Greek philosophers (Davis Zimmerman 2012:777-778; Keener 2013:1176-1177), without considering the Old Testament language: in this instance, πλήθος, which is mostly used in Luke-Acts, occurs in the ecclesiological sense of έκκλησία (congregation), which is the regular rendering of לקהל in DeutLXX.24

The idiom καρδία καὶ ψυχή/ לבֵָב ונְפֶשֶׁ is characteristic of Deuteronomy with which it expresses the wholehearted devotion to YHWH and which ultimately goes back to Deuteronomy 6:5,25 the second part of Israel's basic dogma and norm, the שמע, which proclaims YHWH's exclusive demand in a relationship of love (Braulik 2000:56). Not only every Israelite, but also all Israel are able to love YHWH by realising his social order, the Deuteronomic law (Braulik 2000:56).

The meaning of this formula in Acts is best illustrated by the Palestinian Targum, where the שמע is cited as a profession of faith in the One True God of Israel, which is addressed by the twelve tribes "with a perfect heart" to Jacob/Israel, the father of the nation, while they are gathered around his deathbed (McNamara 2010:189, 193). Given that the שמע (Deut. 6:4-9) was part of the daily morning and evening prayer, which every male Israelite was obliged to recite (Braulik 2000:57; McNamara 2010:65-67, 190) and which the early community of Jerusalem continued daily with one mind in the temple (cf. Acts 2:46a), the phrase expresses the profession of faith in the One True God of the early Jewish-Christian community. With this profession, the community deems itself to be in continuity with Israel. In practice, this profession of faith led to the sharing of possessions within the Primitive Church.

In verse 33, with δύναμις/ מְאדֹ, the third element of the שמע is mentioned (cf. also Pesch 2005:181). The apostles are placed in the middle of the community's life in order to proclaim the new core of their preaching: they add the new profession of faith in the resurrection of the Lord Jesus to the profession they still share with Israel.

By splitting up the שמע in verses 32-33 and combining its elements with different activities of the Primitive Church, this passage presents an inner Biblical ecclesiological interpretation of the way in which YHWH is being loved. With her unanimity and sharing of goods, the Primitive Church loves him with all her "heart" and with all her "being/mind", whereas the apostles' witness to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus with great power shows the community's love with all her "might".

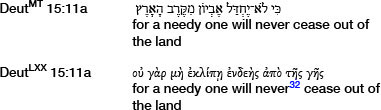

Verse 34a creatively cites26 DeutLXX 15:4a:

Deuteronomy 15:4a is part of the pericope Deuteronomy 15:1-11, which consists of two adjoining and closely connected laws that deal with measures to protect the poor (Braulik 2000:111-113; Lohfink 1996:4-5; Christensen 2001:305-314), namely the remission of debts every seven years (vv. 1-6) and taking care of, and lending to the brother in need (vv. 7-11). The provisions of these two laws that apply to the brother (vv. 2-3) or to the (needy and) poor (man among your) brother(s) (vv. 7, 9, 11) continue the larger section of Deuteronomy 14:22-16:17, which is an expansion of the third commandment (Deut. 5:12-15) (cf. Christensen 2001:309-310).28 The centre of its concentric29 first section is verse 4, which "highlights the primary concerns of the legislation itself, which is intended to make sure that 'there shall not be among you any poor' (v. 4)" (Christensen 2001:310; see also 313). In consideration of the context, "you" does not address all the people of Israel, but only the individual; in fact, not the poor one, but rather the wealthy Israelite (cf. Kessler 2009c:252).

According to the plain sense of the text, שְׁמטִּהָ /ἄφεσις means "a complete discharge of the debt ... however unrealistic this may appear to be in practice" (Christensen 2001:310). Thus, according to Acts, "there was indeed a moment in the history of Christianity in which the utopia became reality. ... Luke therefore looked upon the early Christian community as the fulfilment of the utopia presented in Deuteronomy" (Lohfink 1996:4).30 With regard to verse 11 and despite the conditio humana "that produces poverty, the law here is an attempt to alleviate the suffering of the poor" (Christensen 2001:313).

It appears that the concluding verse 11 of the second law contradicts verse 4:31

This verse perfectly matches the mentality of the ancient Near East and of both Testaments,33 which regarded the poor, who were cared for on the basis of a developed ethos of charity, as an integral part of social life. Despite the theology of Exodus, which states that a marginalised group had been taken out of Egypt's exploitative system and promised a new society, the entire Biblical literature - with two exceptions (Deut. 15:4a; Acts 4:34a) - reckoned the poor as its members. The Hebrew semantic field for the poor or needy consists of seven words and of different names for specific types of poverty or groups, which, in turn, can generally designate the poor as such (Lohfink 1996:7). Deuteronomy only uses the words עני (poor) and אביון (needy), the latter appearing seven34 times. This indicates that these words are not randomly, but consciously placed within the group of five laws on debts.35 These laws are intended to stop and cancel the intolerable course of increasing indebtedness that finally culminates in slavery. In a realistic world view, this group of laws provides well-devised stages for the case of eventual poverty in order to remove it as quickly as possible so that, at the latest, it will be redressed every seventh year (Lohfink 1996:14-15). At this stage, the law reaches its limits and turns into paraenesis by addressing and encouraging the individual to actively combat the poverty of the אח and even taking financial risks.36

7. ACTS 6:1-7

This passage also pursues an ecclesiological purpose by showing that the gathering is about the life and survival of the community of Jesus's disciples (Klein 2015:235, 248). The background of the remark in verse 1 is not poverty of the widows in the Primitve Church in Jerusalem, because - according to Deuteronomy's provision - they no longer belonged to the poor (Lohfink 1996:17). On the contrary, due to a logistic problem within the growing community (Lohfink 1996:17; Witherington 1998:249; Keener 2013:1253, 1260-1268), Luke has the opportunity to emphasise, for the last time, for those who knew the Scriptures that the Deuteronomic project of a counter-society has indeed been realised within Jerusalem's primitive community. This becomes evident from what follows: the seven men act as missionaries, not as bureaucrats, of a charitable organisation (Lohfink 1996:17).

Verse 1 narrates the murmuring of Hellenists37 that "their widows" are being neglected or overseen (Witherington 1998:249) in the daily service. Strikingly, there is no explicit reference to their neediness (Theißen 1996:329). However, according to the Biblical view, it was not even necessary to give a more detailed description. In ancient Near Eastern (legal and narrative) literature, widows are categorised into three areas.38

a. Being legally unprotected, they were a symbol of social vulnerability. Economically, they were not poor per definitionem, although poverty was a realistic fate. However, in some instances, this was only a popular cliche, since widows were, not infrequently, in charge of (large) estates or households and, though being liminal persons, they participated in a state of wealth.

b. In the religious sphere, widows were associated positively with centres of worship and were deemed to be particularly pious and devout or to have a special relationship with the deity (specifically as intercessors). As liminal persons, they were linked with ideas outside the religious mainstream and, by nature, with the realities and the realm of death.

c. In terms of sexuality, widows were viewed as either chaste non-sexual women living in seclusion outside of society, or sexual women living within the bounds of societal (re)marriage prescriptions, or sexually dangerous women who threaten the social order with the paradigmatic sins of adultery and prostitution.

In light of these perspectives, the Deuteronomic legislation concerning widows serves a twofold purpose.39 First, economically, the Deuteronomic laws obligate all Israel to care financially for them, thus incorporating them together with the other marginal groups into the regular societal economic life. Secondly, as a consequence, widows were obliged to lead their lives according to the Deuteronomic religious programme.

In the Book of Deuteronomy, the classic pair אַלמְנָהָ (widow) and יתום (orphan) is not used in the group of the laws on debts that make stipulations for the poor, but in the group of laws that provide for the personae miserabiles who are not counted among the poor.40 The extended triadic formula of sojourner (גר, προσήλυτος), orphan (תום;, ορφανός), and widow (אלמנה, χήρα), which appears seven times,41 is mainly related to those social groups that do not have landed property or that cannot provide for themselves. The numerically calculated fourteen laws dealing with these groups42 are intended to guarantee the supply of food and the joy of the festivals in the project of a new society on the basis of a normal system of exchange of goods (cf. Lohfink 1996:10).43

To summarise, as in Deuteronomy, the widows44 in Acts 6:1 represent those marginalised groups that are entitled, in the new counter-society, to obtain "food" through "the Seven" and "the joy of festivals" through "the Twelve".

These seven men have to be of good reputation, full of the Spirit and of wisdom (v. 3). This overqualification can more easily be understood against its Biblical background. According to the law of the triennial tithe, Deuteronomy 14:28-29, in the third and sixth years, the tithe was not brought to the central sanctuary, but was set aside in the native towns as a kind of social insurance and stockpiled for distribution among those who are indigent or in need of public assistance (Braulik 2000:110; Christensen 2001:303; Heller 2007:3). When those who were socially weak or belonged to marginalised groups of society were able to eat to their fill, YHWH would bless all human activities (v. 29) (Braulik 2000:110). This law of the annual and triennial tithes (Deut. 14:22-29) was later used to shape Joseph's story in Egypt (Gen. 37, 39-50) (Christensen 2001:303-304). In his task to ensure the supply of Egypt with food, Joseph is characterised as a discerning (Gen. 41:33, 39: נָבוןֺ /φρόνιμος) and wise (Gen. 41:33, 39:חָכםָ /συνετός) man, who has the Spirit of God in him (Gen. 41:38: אֲשֶׁר רוּחַ אֱלֹהִים בּוֺ vyai/cνθρωπος ὃς ἔχει πνεῦμα θεοῦ ἐν αὐτῷ. In Deuteronomy 1:13-15, those men (vv. 13, 15: אנשים = ἄνδρας; cf. Acts 6:3) whom Moses appoints and establishes (vv. 13: καταστήσω; 15: κατέστησα; cf. Acts 6:3: καταστήσομεν) to assist him as leaders, have to be wise (vv. 13, 15: חכמים , σοφούς; cf. Acts 6:3), understanding (v. 13 [15lxx]: נבונים , έπιστήμονας), and known vv. 13, 15: ידְֻעיִם , συνετούς; cf. Acts 6:3: μαρτυρουμένους) to Israel's tribes. The required qualities attest to the fact that, despite their military grades and their relations to the tribes, royal officials were the paradigm, with Joseph being the ideal (cf. Gen. 41:33, 39) (Braulik 2000:24). Finally, Deuteronomy 34:9 declares with reference to Numbers 27:15-23 (Braulik 1992:246; Pearce 1995:483) that Joshua was filled with the spirit of wisdom (מָלֵא רוּחַ חָכְמָה /ἐνεπλήσθη πνεύματος συνέσεως; cf. Acts 6:3).

Therefore, in comparison with Acts 6:1-7, one can conclude that the qualifications of the seven men chosen by the congregation of the disciples are phrased with the help of Deuteronomic linguistic elements,45 in order to suggest that they must have similar qualities of leadership to those of Joseph and Joshua.

Against the background of Deuteronomy, the number "seven" has an additional dimension, since it points to the theological importance of an expression (Braulik 2012b:560). In his portrayal of the ideal Jewish constitution in Antiquitates 4.214, Josephus mentions a group of seven men as local executive body in authoritative positions in connection with his interpretation of Deuteronomy 16:18. It is likely that he interprets this verse according to the tradition of his time.46 Furthermore, Deuteronomy 16:18-20 forms a perfect setting for the character traits of the Seven of Acts 6:3. The judges and officials who are to be appointed in the local settlements are urged neither to pervert judgement, nor to show partiality, nor to take a bribe, but simply to pursue justice.

In verse 6, the identification of Nicolas as προσήλυτος refers to the second Deuteronomic persona miserabilis - to the .47 .גֵּר In Acts, this term is used as Jewish-Greek religious terminus technicus, which has evolved in the Greek-Roman Jewish diaspora for those who had fully converted to Judaism through circumcision, irrespective of their race or social status (Kuhn 1990:730-731, 734). In the Deuteronomic social law, גר denotes the sojourner who has to be taken care of, because economically he is not supported by a family that owns landed estate.48 The protection of the גר (and the fringes of society) establishes and preserves the basic social nature of this law, and the care for the sojourner indicates the stabilisation of society (Ebach 2014:61). By way of collective memory, his need for help at the same time reminds Israel of her need in Egypt and that it is Israel's task to maintain and stabilise the present autarchy (Ebach 2014:61). With regard to Acts, this implies that, despite its technical use, the Hebrew term connotated the need for protection and help at least for the Hebrewspeaking members of the Primitive Church. It is subtleness at its highest that (at least) one persona miserabilis is (if not all seven together are) entrusted with the care for other personae miserabiles. Their service at tables enables congregational life in practice (Klein 2015:247), in continuation of the regulations of the Deuteronomic social law.

The strange and unique statement (Lake & Cadbury 1933:66) "that a great multitude of the priests became obedient to the faith" (v. 7) mentions the last member of the Deuteronomic personae miserabiles. In Deuteronomy 18:1, the formula לַכֹּהֲנִים הַלְוִיִּם כָּל־שֵׁבֶט לֵוִי (the Levite-priests, i.e. all the tribe of Levi) provides the key for understanding the texts. This, in principle, proclaims the Levites' exclusive claim to the priesthood at YHWH's central sanctuary (Kellermann 1984:513; Braulik 1992:130-131). The law of the Levitical priests (Deut. 18:1-8) makes provision for the support of those Levites "who serve at the central sanctuary and thus are called 'Levite priests' or simply 'priests' (1.3f)" (Braulik 1992:130).

Contrary to the stipulation49 of this law that, for these Levite priests, there shall not be a territorial inheritance with Israel (v. 1), Acts 4:36-37 mentions the Cypriot Levite Joseph Barnabas who had sold a field which he had owned. This was one reason why the term "Levite" did not match the context of Acts 6:1-7. The second reason for Luke to have rather used the term "priest" instead of "Levite" is the fact that, according to the language regime of the law of the priests and of Deuteronomy, the term "Levite" is an ethnic identifier, whereas the term "priest" is used whenever the Levite's priestly function is verbalised (Braulik 1992:130-131). These Levite priests served in the Temple in Jerusalem and became obedient to the faith and thus (implicitly) qualified for receiving provision for their needs from the Primitive Church.

Viewed as such, Acts 6:1-7 can be interpreted as an ecclesiological summary that the Primitive Church in Jerusalem met with the Deuteronomic paraenesis to care for the personae miserabiles and that the congregation created the infrastructure which was necessary to carry this out.

8. CONCLUSION

Deuteronomy is the pivotal Biblical book for the theological interpretation of Acts 2:42-47, 4:32-35, and 6:1-7. Hermeneutically, both Deuteronomy (cf. Braulik 2012a:177) and Acts are narratives. Deuteronomy sketches its counter-society by using legal terminology with paraenetic intention. Luke presents his ecclesiological50 project of the ideal Christian community by reverting to this Deuteronomic concept and interlacing Deuteronomic terminology into his narrative.

The history of exegesis shows various theological approaches to, and diverse moral interpretations of Luke's depictions of the Primitive Church (Hume 2011:1-6, 13-23). Unfortunately, God's new society has come a long way from the counter-society Deuteronomy has drawn up and yet again takes poverty for granted (Lohfink 1996:18). However, since the Old Testament is part of the Christian Bible, there is no reason to ignore the Old Testament economic law in the easy-going way it is usually done (Kessler 2009a:30). "There are . poor people in our world and there are too many of them. For us it is almost impossible to conceive of a world in which there are no poor people" (Lohfink 1996:4). The Deuteronomic project and the Lucan

model for all future forms of a Christian society ... in which there are no longer any poor is unfortunately still open. On the other hand, the same project would no longer be a utopia if there were Christians who would take the Bible seriously (Lohfink 1996:4; cf. also Kessler 2009a:30).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bauer, W. & Aland, K. 19886. Griechisch-deutsches Wörterbuch zu den Schriften des Neuen Testaments und der frühchristlichen Literatur. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter. [ Links ]

Berger, K. 1977. Exegese des Neuen Testaments. Neue Wege vom Text zur Auslegung. Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer. UTB 658. [ Links ]

Berger, P.L. & Luckmann, T. 1991. The social construction of reality. A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Bichler, R. 2008. Utopie und gesellschaftlicher Wandel. Eine Studie am Beispiel der griechisch-hellenistischen Welt. In: R. Bichler, Historiographie - Ethnographie - Utopie. Gesammelte Schriften. Teil 2. Studien zur Utopie und der Imagination fremder Welten (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz; Philippika 18,2), pp. 11-29. [ Links ]

Braulik, G. 1979. Sage, was du glaubst. Das älteste Credo der Bibel - Impuls in neuester Zeit. Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk. [ Links ]

Braulik, G. 1992. Deuteronomium 16,18-34,12. Würzburg: Echter Verlag. Die Neue Echter Bibel 28. [ Links ]

Braulik, G. 1994a. The joy of the feast. The conception of the cult in Deuteronomy - the oldest Biblical festival theory. In: G. Braulik, The theology of Deuteronomy. Collected essays (Richland Hills: BIBAL Press; BIBAL Collected Essays 2), pp. 27-65. [ Links ]

Braulik, G. 1994b. Commemoration of passion and feast of joy. Popular liturgy according to the festival calendar of the Book of Deuteronomy (Deut 16:1-17). In: G. Braulik, The theology of Deuteronomy. Collected essays (Richland Hills: BIBAL Press, BIBAL Collected Essays 2), pp. 67-85. [ Links ]

Braulik, G. 1999. Were women, too, allowed to offer sacrifices in Israel? Observations on the meaning and festive form of sacrifice in Deuteronomy. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 55(4):909-942. [ Links ]

Braulik, G. 20002. Deuteronomium 1-16,17. Würzburg: Echter Verlag. Die Neue Echter Bibel 15. [ Links ]

Braulik, G. 2012a8. Das Buch Deuteronomium. In: C. Frevel (ed.), Einleitung in das Alte Testament (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer; KStTh 1,1), pp. 163-188. [ Links ]

Braulik, G. 2012b. Die Liebe zwischen Gott und Israel. Zur theologischen Mitte des Buches Deuteronomium. Internazionale Katholische Zeitschrift 41:549-564. [ Links ]

Bruce, F.F. 19903. The Acts of the Apostles. The Greek text with introduction and commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Christensen, D.L. 2001. Deuteronomy 1:1-21:9. Revised edition. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers. WBC 6A. [ Links ]

Collins, J.J. 2000. Models of utopia in the Biblical tradition. In: S.M. Olyan & R.C. Culley (ed.), "A wise and discerning mind". Essays in honor of Burke O. Long (Providence, Rhode Island: Brown Judaic Studies; BJSt 325), pp. 51-67. [ Links ]

Davis Zimmerman, K.-S. 2012. Neither social revolution nor utopian ideal. A fresh look at Luke's community of goods practice for Christian economic reflection in Acts 4:32-35. HeyJ 53:777-786. [ Links ]

Dogniez, C. & Harl, M. 1992. Le Deutéronome. Traduction du texte grec de la Septante, introduction et notes. Paris: Editions du Cerf. [ Links ]

Ebach, R. 2014. Das Fremde und das Eigene. Die Fremdendarstellungen des Deuteronomiums im Kontext israelitischer Identitätskonstruktionen. Berlin/ Boston: De Gruyter. BZAW 471. [ Links ]

Heller, R.L. 2007. The "widow" in Deuteronomy. Beneficiary of compassion and co-option. In: C.J. Roetzel & R.L. Foster (ed.), The impartial God. Essays in Biblical studies in honor of Jouette M. Bassler (Sheffield: Phoenix Press; NTM 22), pp. 1-11. [ Links ]

Hübenthal, S. 2015. Erfahrung, die sich lesbar macht. Kol und 2 Thess als fiktionale Texte. In: S. Luther et al. (ed.), Wie Geschichten Geschichte schreiben. Frühchristliche Literatur zwischen Faktualität und Fiktionalität (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck; WUNT 2.395), pp. 295-339. [ Links ]

Hume, D.A. 2011. The early Christian community. A narrative analysis of Acts 2:41-47 and 4:32-35. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. WUNT 2.298. [ Links ]

Keener, C. 2013. Acts. An exegetical commentary 2. 3:1-14:28. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Kellermann, D. 1984. Art. לוי ThWAT 4:499-521. [ Links ]

Kessler, R. 2009a. Das Wirtschaftsrecht der Tora. In: R. Kessler, Studien zur Sozialgeschichte Israels (Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk; SBAB 46), pp. 11-30. [ Links ]

Kessler, R. 2009b. Zur israelitischen Löserinstitution. In: R. Kessler, Studien zur Sozialgeschichte Israels (Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk; SBAB 46), pp. 74-84. [ Links ]

Kessler, R. 2009c. Göjim in Dtn 15,6; 28,12. "Völker" oder "Heiden"? In: R. Kessler, Studien zur Sozialgeschichte Israels (Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk; SBAB 46), pp. 251-255. [ Links ]

Kessler, R. 2009d. Die Rolle des Armen für Gerechtigkeit und Sünde des Reichen: Hintergrund und Bedeutung von Dtn 15,9; 24,13.15. In: R. Kessler, Studien zur Sozialgeschichte Israels (Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk; SBAB 46), pp. 256-266. [ Links ]

Klein, H.H. 2015. Sie waren versammelt. Die Anfänge christlicher Versammlungen nach Apg 1-6. Münster: Aschendorff. FTS 72. [ Links ]

Kuhn, K.G. 1990. Art. προσήλυτος. ThWNT 6:727-745. [ Links ]

Labahn, M. 2007. Deuteronomy in John's Gospel. In: M.J.J. Menken & S. Moyise (eds.), Deuteronomy in the New Testament (London: T. & T. Clark; LNTS 358), pp. 82-98. [ Links ]

Lake, K. & Cadbury, H.J. 1933. The beginnings of Christianity. Part I. The Acts of the Apostles. Volume IV. English translation and commentary. London: MacMillan. [ Links ]

Lausberg, H. 19903. Handbuch der literarischen Rhetorik. Eine Grundlegung der Literaturwissenschaft. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. [ Links ]

Levinson, B.M. 2003. You must not add anything to what I command you. Paradoxes of canon and authorship in Ancient Israel. Numen 50:1-51. [ Links ]

Lim, T.H. 2007. Deuteronomy in the Judaism of the Second Temple Period. In: M.J.J. Menken & S. Moyise (eds.), Deuteronomy in the New Testament (London: T. & T. Clark; LNTS 358), pp. 6-26. [ Links ]

Lohfink, G. 2015. Wie hat Jesus Gemeinde gewollt? Kirche im Kontrast. Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk. [ Links ]

Lohfink, G. & Lohfink, N. 1984. "Kontrastgesellschaft". Eine Antwort an David Seeber. Herder Korrespondenz 38:189-192. [ Links ]

Lohfink, N. 1996. The laws of Deuteronomy. A utopian project for a world without any poor. Scripture Bulletin 26:2-19. [ Links ]

LXX. 20062. J.W. Wevers (ed.), Deuteronomium. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. Septuaginta: Vetus Testamentum Graece 3.2. [ Links ]

Marguerat, D. 2011. Lukas, der erste christliche Historiker. Eine Studie zur Apostelgeschichte. Zürich: TVZ. AThANT 92. [ Links ]

Marguerat, D. 20152. Les Actes des Apôtres (1-12). Geneve: Labor et Fides. Commentaire du Nouveau Testament Va. [ Links ]

McNamara, M. 20102. Targum and Testament revisited. Aramaic paraphrases of the Hebrew Bible. A light on the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Mitchell, A.C. 1992. The social function of friendship in Acts 2:44-47 and 4:32-37. JBL 111(2):255-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3267543 [ Links ]

MT. 2007. C. McCarthy (ed.), אלה הדברים Deuteronomy. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. Biblia Hebraica Quinta 5. [ Links ]

NA28. 201228. B. Aland & K. Aland et al. (eds.), Novum Testamentum Graece. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. [ Links ]

Pearce, S.J.K. 1995. Flavius Josephus as interpreter of Biblical law. The council of seven and the Levitical servants in Jewish Antiquities 4.214. HeyJ 36:477-492. [ Links ]

Pesch, R. 20053. Die Apostelgeschichte. 1. Teilband. Apg 1-12. Düsseldorf/NeukirchenVluyn: Benziger Verlag/Neukirchener Verlag. EKK 5/1. [ Links ]

Rusam, D. 2007. Deuteronomy in Luke-Acts. In: M.J.J. Menken & S. Moyise (eds.), Deuteronomy in the New Testament (London: T. & T. Clark; LNTS 358), pp. 63-81. [ Links ]

Schmitt, J. 1953. L'Église de Jérusalem ou la "restauration" d'Israel d'après les cinq premiers chapitres des Actes. Revue des Sciences Religieuses 27:209-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/rscir.1953.2015 [ Links ]

Schulmeister, I. 2010. Israels Befreiung aus Ägypten. Eine Formeluntersuchung zur Theologie des Deuteronomiums. Frankfurt/Main: Lang. ÖBS 36. [ Links ]

Siebenthal, H. 2011. Griechische Grammatik zum Neuen Testament. Gießen/Basel: Brunnen/ Immanuel Verlag. [ Links ]

Theissen, G. 1995. Urchristlicher Liebeskommunismus. Zum "Sitz im Leben" des Topos άπαντα κοινά in Apg 2,44 und 4,32. In: T. Fornberg & D. Hellholm (eds.), Texts and contexts. Biblical texts in their textual and situational contexts. Essays in honor of Lars Hartman (Oslo: Scandinavian University Press), pp. 689-712. [ Links ]

Theissen, G. 1996. Hellenisten und Hebräer (Apg 6,1-6). Gab es eine Spaltung der Urgemeinde? In: H. Lichtenberger (ed.), Geschichte - Tradition - Reflexion. Festschrift für Martin Hengel zum 70. Geburtstag. Band 3. Frühes Christentum (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck), pp. 323-343. [ Links ]

Uhlenbruch, F. 2015. The nowhere Bible. Utopia, dystopia, science fiction. Berlin: De Gruyter. SBR 4. [ Links ]

Weinfeld, M. 1992. Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic school. Winona Lake, IND.: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Witherington III, B. 1998. The Acts of the Apostles. A socio-rhetorical commentary. Grand Rapids, MI/Carlisle: Eerdmans/The Paternoster Press. [ Links ]

1 Cf., for example, Mitchell (1992:255-256). Only Schmitt (1953:213-217) pays attention to the importance of the Book of Deuteronomy for the ecclesiology of the early community in Jerusalem.

2 Regardless both of the unsolved problem of the interpretation of the "Hellenists" and "Hebrews" of Acts 6:1 and of the opinio communis that Luke probably was a Christian from a gentile background and a learned man writing likewise for a readership from a gentile background, the focus in this article is on life and practice within the Jerusalem community.

3 My approach to the theory and theology of Deuteronomy is based mainly on the exegetical and theological work of Georg Braulik.

4 The term "counter-society" originates from the definition by Berger & Luckmann (1991:145) that "counter-definitions of reality require counter-societies". Norbert and Gerhard Lohfink introduced this term to Old and New Testament theology, in order to describe the social function of the people of Israel and the Church. Since the Jewish-Christian world-of-interpretation and faith differ from those of gentile societies, both the Old and the New Testament people of God have to be a society in contrast. According to YHWH's will, Israel has to distinguish herself from all nations (cf. Deut. 7:6-8) and, as a holy people, live according to the social order that has been given to her and that stands in contrast to the social orders of all other nations (cf. Deut. 7:11; Lev. 1726). Due to the message of the prophets, Jesus's collecting movement aims at the eschatological true Israel within which this social order is being realised (cf. Lohfink 2015:172-188; Lohfink & Lohfink 1984:190-191).

5 See also Lim (2007:6). According to Lim (2007:6), the importance of this book "for the study of Israel's Scriptures in the New Testament can hardly be exaggerated", and the "study of quotations ... hardly exhausts the influence of Deuteronomy on the New Testament and other Jewish writers of the Second Temple Period". In the Qumran library, it "is the second best attested Biblical book . only surpassed by the Psalms" (Lim 2007:11).

6 The author of the Gospel of John, for example, adjusts the Old Testament pre-text to the Gospel's narrative and argumentative background "even by seriously rephrasing the wording of his pre-text" (Labahn 2007:87).

7 However, is it really true that only explicit quotations literarily revert to the Old Testament and that all other kinds of references render independent late Jewish traditions? (cf. Berger 1977:170). Furthermore, is it also true that Old Testament quotations are very often renderings of fixed traditions of interpretations? (cf. Berger 1977:170). Is this position not an underestimation of the relevance of the Old Testament and its influence on Judaism and the New Testament?

8 The respective texts are Luke 4:1-13: Deut. 6:13, 16; 8:3 (all three quotations "are no doubt originally derived from the LXX" [Rusam 2007:65]); Luke 10:27: Deut. 6:5 (or 10:12); Luke 18:20: Deut. 5:16-20; Luke 20:28: Deut. 25:5f.; Acts 3:22: Deut. 18:15, 19 ("There is no doubt that it is a LXX quotation." [Rusam 2007:78]); Acts 7:37: Deut. 18:15 (cf. Rusam 2007:63, 65-75). This is also true of the numerous allusions to Deuteronomy. In the Book of Acts, especially the speeches of Stephen, Peter and Paul abound in allusions to Deuteronomy (cf. Rusam 2007:65): Acts 7:5: Deut. 2:5; Acts 7:38: Deut. 4:10; 9:10; Acts 7:41: Deut. 4:28; Acts 7:45: Deut. 32:49; Acts 10:34: Deut. 10:17; Acts 13:17: Deut. 4:34, 37; 5:15; 9:26, 29; 10:15; Acts 13:18: Deut. 1:31; Acts 13:19: Deut. 7:1; Acts 17:26: Deut. 32:8.

9 Cf. also Braulik (2012a:187).

10 Cf. Lohfink (1996:3-6, 16-17); Pesch (2005:131, 133, 184-188); Kessler (2009a:30); Braulik (2012a:175). For the Bible as utopia, cf. Uhlenbruch (2015:18-22). According to modern narrative theories, Acts could be interpreted as a text of factual narratives with fictionalising storytelling techniques. In other words, by applying literary storytelling techniques that are subject to literary narrative conventions, Luke is referring to a true story (cf. Hübenthal 2015:302, 305-306).

11 As to the heterogeneous term and the improper anachronistic modern (totalitarian, communist, socialistic) categories of its interpretation, which fail to notice the basic social, economic, cultural, technical and political differences between antiquity and the dawning industrial age, cf. Bichler (2008:11, 21-22). For the anachronism of reading the Bible as utopian literature, cf. Uhlenbruch (2015:36-38).

12 Cf. Bichler (2008:16, 20). In general, from the economic point of view, utopias are rather retrograde than progressive (cf. Bichler 2008:16 n. 25).

13 The spiritualised community of Qumran also belongs to this category (Collins 2000:63-65). For the four kinds of utopia in the corpus of Biblical and early Jewish writings, cf. Collins (2000:52).

14 Cf. Braulik (2012a:182-184, 187).

15 The society delineated in the Bible is not a society for everybody, but solely one that is meant "for Israel and then subsequently for the messianic community of Christians" (Lohfink 1996:3).

16 Cf., for example, Deut. 6:21-25 (catechetic creed); 26:5-10 (short historic creed).

17 According to Deuteronomy 15:12, את does not have a gender-specific connotation, but also includes women (cf. Braulik 2012a:184).

18 Other references to, or citations of Deuteronomy in Acts 1-6 (for example, 3:23) are not considered.

19 Cf. Witherington (1998:156-159), who distinguishes between summary statements and summary passages (cf. Witherington 1998:157, 159) and who points out that these kinds of generalising summary passages are exclusively connected with the earliest Christian life in Jerusalem (Acts 1-8) and do not occur in later chapters of Acts (cf. Witherington 1998:159).

20 However, the common life of the first Christians transcended the mere pagan ideal by being "friendship between socially unequal persons, as well as a new motivational guide for social relations: concern for those most in need" (Davis Zimmerman 2012:777; see also 780).

21 The phrase occurs seven times: Deut. 4:34; 6:22; 7:19; 11:3; 26:8; 29:2; 34:11 (cf. Braulik 1979:75-76; Weinfeld 1992:330; Schulmeister 2010:129-145).

22 אתות: Ex. 4:8, 9, 17, 28, 30; מופתים: Ex. 4:21 (cf. Braulik 1979:75; 1992:194).

23 For the rhetorical use of metathesis and the postposition of the most powerful element as a kind of short form of gradation, cf. Lausberg (1990:245-246, 440-441).

24 Cf. Bruce (1990:159, 166), who refers to Exod 12:6 and 2 Chr 31:18. As terminus technicus in the linguistic usage of religious associations, it denotes the associates' totality (cf. Bauer & Aland 1988:1344-1345).

25 Cf. Dogniez & Harl (1992:154). The Deuteronomic phraseבּכָל־לֵבָב וּבְכָל־נֶפֶשׁ ./ἐξ ὅλης τῆς καρδίας καὶ ἐξ ὅλης τῆς ψυχῆς

is found in Deut. 4:29; 10:12; 11:13, 18; 13:3(4); 26:16; 30:2, 6, 10 (cf. Weinfeld 1992:334; Witherington 1998:206; Keener 2013:1176 n. 31).

26 If one defines quotation as "an (almost) non-modified" and through the use of formulae "explicitly marked taking over of a text or part of a text by a new text" (Rusam 2007:63), Luke does not cite Deuteronomy. However, written copies and word-for-word agreement are the exceptional case in the course of tradition (cf. Berger 1977:180-181). Quotation and allusion are special forms in the use of sources, but citations are not a mere repetition of a text, since its original context has been lost and is no longer valid (cf. Berger 1977:181). In quotations, the authority of the original meaning is simultaneously centered in one aspect and restricted to it (cf. Berger 1977:181). Due to the "recognizable verbal identity" (Labahn 2007:88) with the pre-text, one may classify Deut 15:4a as an unmarked quotation.

27 For substantival usage of adjectives, cf. Siebenthal (2011:198f., §137c).

28 According to Braulik (2012a:176), the cluster of laws (Deut. 14:22-16:17) interprets the third commandment from the point of view of the realisation of cult and brotherliness in holy rhythms.

29 A 15:1f. - B 15:3 - X 15:4 - B' 15:5 - A' 15:6 (cf. Christensen 2001:310).

30 According to Pesch (2005:184-185), neither the pre-Lucan tradition nor Luke himself speaks of an ideal or utopia, but of the fulfilment of the Biblical-eschatological promise in Deuteronomy 15:4 within the eschatological community. According to Marguerat (2015:170), the Greek translation of the Septuagint has turned the Hebrew prescription into an eschatological promise, cited by Luke, in order to state its fulfilment in the lives of the first Christians.

31 For the interpretation, cf. Lohfink (1996:6f., 14). In the Massoretic text, utopian vision and pragmatic reality are separated by one and the same particle (כי) that adds declamatory force to the initial assertion in verse 4 and forms the conditional statement in verse 11 (cf. Levinson 2003:1-2).

32 For οϋ μή + subj. aor. as most intense negative, cf. Siebenthal (2011:355, §§210-211).

33 In Mark 11:7, Jesus also refers to this verse (cf. Lohfink 1996:4).

34 Groups of seven are "clearly intentional and to a certain degree emphatic" (Lohfink 1996:8); cf. also Braulik (2012a:170).

35 Cf. Lohfink (1996:8-10): עני Deut. 15:11; 24:12, 14, 15; אביון Deut. 15:4, 7, 9, 11; 24:14. The groups are: Deut. 15:1-6; 15:7-11; 15:12-18; 24:10-13, and 24:14f. For the socio-historical background and the pivotal importance of indebtedness for the social and economic development, cf. Kessler (2009b:74-76).

36 In Deut. 15:1-18, את occurs seven times out of the 29 occurences in Deut. 12-26 (cf. Lohfink 1996:15).

37 Regarding the problem of their identification, cf., for example, Keener (2013:1253-1260).

38 For the following, cf. Heller (2007:5-9).

39 For the following, cf. Heller (2007:10-11).

40 Cf. Lohfink (1996:7, 9-13); Braulik (2000:110); Ebach (2014:42-43). Heller (2007:2, 5) who, like other Biblical scholars, fails to notice that these individuals do not belong to the poor, although he states that widows (and orphans) are not "a rhetorical representation of the poor, but are rather separate from the poor" (Heller 2007:5) and that they "have particular and special rights and privileges distinct from those who are poor and needy in society" (Heller 2007:5).

41 Deut. 14:(28)29; 16:11, 14; 24:19, 20, 21; 26:13.

42 Deut. 5:14; 12:7, 12, 18; 14:26-27, 29; 15:20; 16:11, 14; 24:19, 20, 21; 26:11, 12-13 (cf. Lohfink 1996:11).

43 In the Ancient Near East, the gods and kings took a special (juridical) responsibility for the widows and orphans (cf. Lohfink 1996:7; Ebach 2014:44), with physical and fiscal consequences for these marginalised people. Contrary to Ancient Near Eastern texts, the Book of Deuteronomy prefers the sequence "orphan and widow" and never uses the words separately; furthermore, the word pair is always preceded by גר (sojourner) (cf. Lohfink 1996:8).

44 The orphans of the Deuteronomic classic pair are probably included with the widows through inclusive language, since in the New Testament orphans are not picked out as a central theme at all (only Jas. 1:27; John 14:18 uses figurative language).

45 Luke does not make use of the wording of the LXX, and one gets the impression that he is closer to the MT than to the Greek of the LXX. For example, he translates תכמור with σοφία and not with σύνεσις.

46 Cf. also Josephus, Antiquitates 4.287; War 2.571 (cf. Pearce 1995:481-482; Theißen 1996:327; Keener 2013:1278). Acts 6:1-6, which is an idealising account like that of Josephus, supports the assumption that Josephus's seven that are appointed for each city were conceived of as a fraction of the Mosaic model of the seventy that are intended for the entire nation (cf. Pearce 1995:482, 488-489).

47 In theory, the other six men could also have been proselytes who, unlike Nicolas, were known to the Church and need not have been introduced as such.

48 Cf. Ebach (2014:41-52), especially concerning the question as to whether the "resident outsider" was an Israelite or a foreigner.

49 For the problem of land ownership of Levites, cf. Kellermann (1984:518); Braulik (1992:131).

50 For Deuteronomy as Old Testament ecclesiology, cf. Braulik (2012b:550, 554-555).