Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.36 n.1 Bloemfontein Jun. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v36i1.7

ARTICLES

The goal of maturity in Ephesians 4:13-16

E.D. Mbennah

Research Unit for Reformed Theology, North-West University, Private Bag X6001, Potchefstroom 2520. E-mail: mbennah@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

In this article, I argue that, in Ephesians 4:1-16, the author underscores spiritual maturity as the bridge between the new identity of the Christian (Eph. 1-3) and the moral code of the Christian life commensurate with the new identity (Eph. 4:17-6:20).1 I interpret Ephesians 4:13 to obtain the meaning of maturity. I critique the most notable interpretations and views in relation to Ephesians 4:13, after which, by way of structural analysis of Ephesians 4:13, I delineate the meaning of maturity and determine that, from its essence, maturity is essential for the Christian. This article provides the modern church an alternative way to view the theme and structure of Ephesians and an interpretation of Ephesians 4:13-16. New Testament scholars as well as church leaders, decision-makers in church work, generally, and Christian education planners will find this article quite engaging.

Keywords: Spiritual maturity, Meaning, Imperative, Ephesians 4:13-16, New Testament interpretation

Trefwoorde: Geestelike volwassenheid; Betekenis; Imperatief; Efesiërs 4:13-16; Nuwe Testament interpretasie

1. PROBLEM STATEMENT

The relevance of Ephesians across space and time is assumed.2 The majority of the researchers3 on the Epistle advance a two-section structure, Ephesians 1:1-3:21 and Ephesians 4:1-6:20, the one section presenting an articulation of the new identity of the gentiles and all its divine origins, and the other presenting the code of conduct for the new people. However, this manner of dividing the Epistle could be viewed as a reflection of failure to notice that the code of conduct does, in fact, begin from 4:17. It is from this part of Chapter 4 of the Epistle that Paul begins to call for a radical behavioural change for the readers, based on faith in Christ. It is quite likely that this failure led to treating Ephesians 4:1-16 as a pericope on unity, in order to make it an ethical matter. An analysis of the Epistle reveals that it has three primary sections.

The first, contained in Ephesians 1:1-3:21, spells out the new identity and new state of the Gentile Christians to whom he is writing. The essence of the message is that, by the love and grace of God (Eph. 1:4-7, 2:4), they who were once dead (Eph. 2:1, 5), outside the covenantal promises (Eph. 2:12), far from Christ and without God in the world (Eph. 2:12), are now alive (Eph. 2:5), forgiven and reconciled to Christ and to other believers (Eph. 2:13, 14, 16), have become part of the family of God (Eph. 2:19), and part of the building and the temple of God (Eph. 2:21, 22). They are now out of the fateful degradation of their former hopeless heathen condition of being lost in sin (cf. Eph. 2:6). They are now an integral part of the church -the cosmic body of Christ (Eph. 3:6); recipients of all the spiritual blessings of God, and they are the blessed people of God like the Jewish Christians or any of those who became Christians first (Eph. 1:3, 6, 13, 18; 3:6). As such they have acquired, by the bestowal of God, a new nature, a new status and, hence, a new identity. Paul refers to this new identity as a calling (Eph. 4:1).

The third section, contained in Ephesians 4:17-6:20, spells out the standards of personal as well as communal behaviour and relationships in the household for the Gentile Christians commensurate with their new identity: for example, in terms of speech, work ethic and general behaviour (Eph. 4:25-32); sexual behaviour (Eph. 5:3-6); marriage (Eph. 5:22-330; relationship between parents and children (Eph. 6:1-4); relationships at the workplace, specifically between the slave owners and the slaves (Eph. 6:5-9), and preparedness to resist and confront evil (Eph. 6:10-18). This is a radical change in behaviour that is to be completely different and strange to the system and pattern of the pagans. Paul is explicit in his call for the Gentile Christians to embrace this radical change from their hitherto way of life and invites them to do so with a sense of great celebration.

In between these two sections is the second section, that is, Ephesians 4:1-16. It is apparent that unity is a key theme in this section. The church is to be eager to maintain the unity or oneness of the Spirit in the bond of peace (Eph. 4:3). However, whereas "working in a manner worthy of the calling" (Eph. 4:1), "with the humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another in love" (Eph. 4:2) may be manifestations of unity, they may not produce unity. I argue that these are subsequent to maturity. Thus, contrary to many an interpreter of the Epistle who concludes that the purpose of Ephesians 4:1-16 is unity, my proposition is that the primary purpose of this section is to call the recipients of this Epistle to grow towards the goal of spiritual maturity, which is requisite for them to walk worthy of the calling they have received, including maintaining the unity of the Spirit, with humility, gentleness and patience, and bearing with one another in love. Being in the middle of the foundational articulation of the identity and state of the Christian and Christian responsibility in everyday living possibly implies that spiritual maturity is central in terms of what a Christian is and does.

It appears that Ephesians 4:13 is the only passage in the New Testament where the ultimate goal of spiritual maturity is specified. The question, then, is: According to this pericope, what is the ultimate goal of maturity and why is maturity essential for the Christian? To address the problem, I shall first do a micro-level thought structure analysis of Ephesians 4:1-16. Thereafter, I shall evaluate the most salient interpretations of Ephesians 4:13, after which I shall do an analysis of Ephesians 4:13-16, to determine the goal of spiritual maturity according to this text.

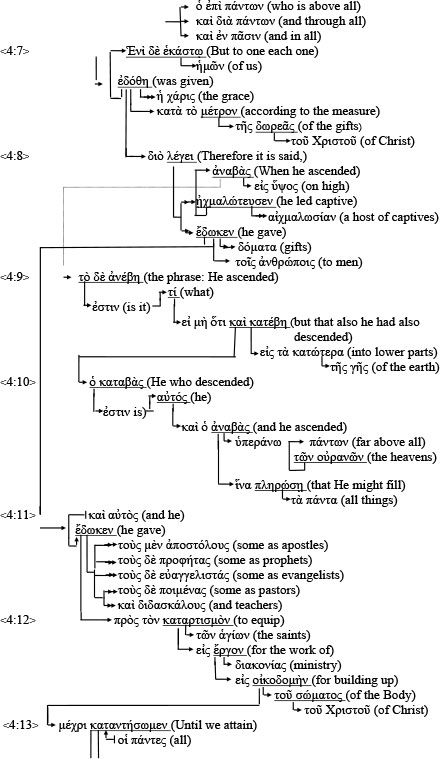

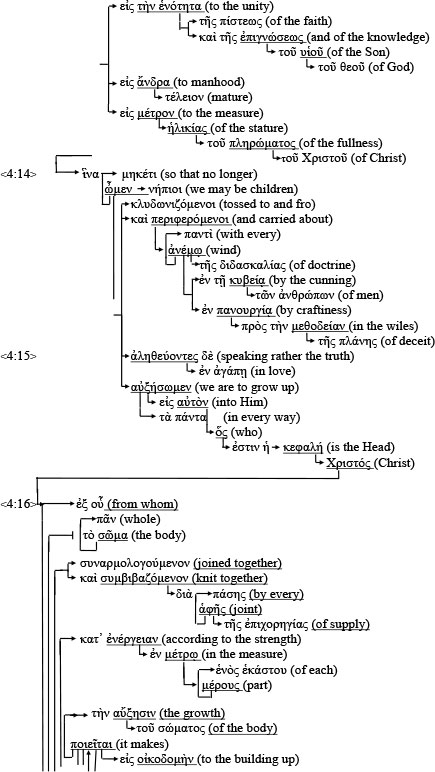

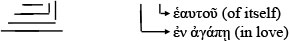

2. THOUGHT STRUCTURE OF EPHESIANS 4:1-16

In order to be able to interpret Ephesians 4:13, it is important that the syntactical function of the verse within the wider context of Ephesians 4:1-16 is determined. Towards that end, I shall do a micro-level analysis of the thought structure4 of Ephesians 4:1-16.

2.1 The thought structure on micro-level

2.2 Ephesians 4:13 in the context of Ephesians 4:1-16

Since Ephesians 4:13 is a long clause within a long sentence beginning from Ephesians 4:11 and ending at Ephesians 4:14, the interpretation of Ephesians 4:13 requires taking into consideration thisimmediate textual context. However, since Ephesians 4:11-14 is itself situated within Ephesians 4:1-165, it is necessary to consider another broader immediate textual context when interpreting Ephesians 4:13. Paul restates the fact that the recipients have received a calling, which is the new identity advanced in Ephesians 1-3; he thus urges them to live accordingly (Eph. 4:2) and reminds them of the oneness there is - one body, one Spirit, one hope, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God (Eph. 4:4-6). Paul then introduces a new subject altogether, namely what Christ has done and the purpose for which Christ did it (Eph. 4:7-10).

Thereafter, Paul states that Christ has appointed some as apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers, and he states the objective of these appointments (Eph. 4:11).This is followed in Ephesians 4:12-14 by some clauses that have been the subject of wide discussion (cf.,for example, Hendriksen 1967:197-201; Lincoln 1990:248-259; Schnackenburg 1991:182-187; Heehner 2002:501-580). At issue in these discussions is first, whether the clauses relate to those he appointed or to Christ Himself and secondly, what relationship exists between theclauses. It is important to resolve theseissues in order to determine the extent, if any, to which they inform a valid interpretation of Ephesians 4:13. Three successive prepositional phrases follow the statement that Christ appointed apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers (Ephh 4:11): for the equipment of the saints, for the work of the ministry, and for building up the body of Christ. How do these clauses relate to each other, and how do they pertain to the gifts Christ has given and to the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers he appointed?

Three basic propositions can be constructed from a review of the most pertinent literature, to the explored below. Each of those propositions is evaluated against the view that Ephesians 4:1-16 is about maturity. An alternative proposition is suggested (cf. section 2.6).

2.3 The parallel proposition of the three clauses

One proposition is that these clauses are viewed as coordinates, all linked to "he gave", whereby it is understood that Christ appointed the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers in Ephesians 4:11 to achieve all the three clauses. Those who hold this view (for example, Best 1998:399; Lincoln 1990:255) argue that the clauses are non-dependent, but parallel and that they mutually reflect on each other, with none of them more important than the others. The arguments in support of their view are that there are no grammatical or linguistic grounds to warrant or require making specific links between the three clauses. They argue further that linking these clauses would constitute a clerically dominated interpretation, instead of emphasising the active role and participation of all believers. Such domination by the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers would supposedly be contrary to the essence of Ephesians 4:7 and 4:16. According to this view, those whom Christ appointed are to do three things: they are to perfect the saints, do the ministry, and build up the body of Christ.

However, this view is not convincing, because Ephesians 4:11 clearly focuses on the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers appointed by Christ, not all believers, except the believers as recipients of their respective ministries. Furthermore, the fact that the active role of the believers is stated in Ephesians 4:7 and 4:16 confirms that, in Ephesians 4:12, Paul's direct focus is only on the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers. A desire for both a democratic view of church polity and a rejection of church hierarchy simply does not constitute a valid basis for the parallel view. I would argue further that, on the basis of what is to follow the clauses, namely, Ephesians 4:13, a parallel proposition is not tenable. A parallel view of the three clauses would mean that the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers are to continue working "for the equipment of the saints", "for the work of the ministry", and "for building up the body of Christ", until they all attain such full maturity that each member is meaningfully and effectively participating in the life of the body of Christ. If the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers must also do the works of service and to build the body of Christ, it would mean that the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers do all the work and that the remainder of the saints would not be expected to do any such tasks. At what point would the remainder of the believers be sufficiently mature to start participating in the life of the body of Christ? If the remainder of the saints were to function in any way in the body of Christ, how would they have to relate with the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers appointed by Christ? It is unlikely that Paul would have meant that the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers were intended to be the only ones to work directly for achieving this ultimate goal.

2.4 The sequence proposition of the three clauses

In the sequence proposition, the clause "for the equipment of the saints" is linked with "he gave"; "for the work of the ministry" is taken to be subordinate to "the equipment of the saints", and the phrase "for building up the body of Christ" is understood as dependent on both the phrases "for the equipment of the saints" and "for the work of the ministry" together. Such understanding would mean that Christ gave to the Church the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers to equip the saints, so that the saints effectively exercise their gifts in service, in order that both the officers and the common service of the believers would build the body of Christ. In line with this view, O"Brien (1999:302) argues that there is a movement of discussion from the work of the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers (Eph. 4:11) to that of the saints (Eph. 4:12a, 12c). Based on this view, the whole body ultimately grows from the head, as each part does its work (Eph. 4:16), as the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers listed in Ephesians 4:11 supposedly support and direct other members of the church to carry out their ministries for the good of the whole.

From this proposition, it would follow that the building up of the body of Christ would continue "until we all attain the unity of faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature man, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ". This would enable a relationship between what the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers and the believers do and the building up of the body of Christ, with "until we all attain the unity of faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to the mature man, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ", either as part of the stated goal, or simply as a consequent by-product of the process. However, there is no clarity as to whether "until we all attain the unity of faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to the mature man, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ" is a culmination of the building up of the body of Christ, or an ultimate stage of the objective of "equipping the saints".

2.5 The mixed proposition of the three clauses

It is posited that the punctuation between "for the equipment of the saints" and "for the work of the ministry" be removed (Boice 2007:140) -supposedly because it is there by mistake - so that the two clauses are, in fact, one clause with one idea: "for the equipment of the saints for the work of the ministry". This is what I call the mixed proposition. This would thus imply that "for the work of the ministry" is the objective of the work of the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers in "bringing the saints to completion". This means that the sole purpose of equipping the saints would be for the saints to be capable of, and accustomed to doing the works of service. This is perceived not only as necessary, but also as the methodology for "building up of the body of Christ". It would then follow that, in carrying out the works of service, the saints play their part in building up the body of Christ. This means that the building up of the body of Christ is not a direct responsibility of the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers. In support of this view, the change in preposition from πρòς to εις between the first and second phrases is regarded as a sign that the phrases are not coordinate to Ephesians 4:7.

This proposition is also untenable, because, as some (for example, Lincoln 1990:253; Muddiman 2001:200) have argued, the change of preposition cannot bear the weight of such an argument, and there are, in fact, no grammatical or linguistic grounds for making a specific link between the first and second phrases. It is also argued that, although it is grammatically correct to combine "for the equipment of the saints" and "for the works of service", which would mean that the entire community is to do the works of service, such a combination would render the clause "for building up the body of Christ" ambiguous - either intended to explain what "the works of service" means as the activity of all saints, or to explain what "for the equipment of the saints" means as the activity of the church leaders.

2.6 Alternative proposition to the three clauses

The meaning of the clause "for the equipment of the saints" is pertinent to understanding its relationship with "for the works of service" and "for building up the body of Christ" and, ultimately, "until we all attain to the unity of faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to be mature man, to measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ".

The meaning range of καταρτισμός includes preparing, completing, training and disciplining, with a view to making the trainee adequate for a specific task or general responsibility (cf. Lincoln 1990; Best 1998; O"Brien 1999; Muddiman 2001). Thus, if it stands alone, the phrase could mean readmit lapsed saints into fellowship, or it could mean to make the saints holy and blameless. I would agree that the notion of making complete, through restoring or training, best fits the context. Thus, from the context of Ephesians 4:7-12, Christ intended that all believers be brought to a state of completion; this would then imply that the saints are equipped for some purpose, namely the "works of service". Christ appointed the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers for the purpose of making God's people fully qualified, so that what has been done for the saints, by the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers and by the saints through the exercise of the gifts in service, is for (the continuous act of) building up the body of Christ. The process of equipping the saints, the execution of the works of service by the saints, and the continuous resultant progression towards the attainment of the goal of building the body of Christ will have to continue "until we all attain the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to the mature man, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ" (Eph. 4:13). Although the building up of the body of Christ is the task of all members of the body (Eph. 4:16), those whom Christ appointed have a distinctive and particularly significant role to play therein: they must equip the members of the body so that they can fulfil their task.

As the saints presumably respond to the equipping process and increasingly put to use their gifts, the body of Christ is being built up. There is a direct purpose of Christ in appointing the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers, namely to equip the saints for works of service. The ultimate intended result reflects the content and the specific objectives of the equipping process. Thus, Christ appointed apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers so that the ministry continues, until the church reaches the goal of maturity stated in Ephesians 4:13.

3. ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION OF EPHESIANS 4:13

μέχρι καταντήσωμεν οί πάντες εις την ενότητα της πίστεως και της έπιγνώσεως του υίοΰ του θεοΰ, εις άνδρα τέλειον, εις μέτρον ηλικίας του πληρώματος του Χριστοΰ.

Till we all come in the unity of the faith, and of the knowledge of the Son of God, unto a perfect man, unto the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ.

3.1 Till we all come

The literal sense of the verb "till we all come" is until we all arrive at a place; thus, primarily a temporal indicator. However, the verb also connotes intentionality to pursue the attainment of a specific state. Thus, μέχρι, "till", has both a prospective force and intentionality (Lincoln 1990:255; O"Brien 1998:303), and the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers are to continue to carry out their task both until the whole church reaches the particular destination stated and in order that the church might reach that destination. In using the word μέχρι, Paul depicts the church as being, or as expected to be, on the way to some specific final spiritual state. The church is to move towards the stated goal and keep moving until she attains that destination (cf. Hodge 1964:230; 1994:139).

The inclusive "all" (οί πάντες) is part of the goal, towards which "all" are to strive until they attain it. Since Paul is writing within the context of the church, the "all", in this instance, would refer only to the body of Christ, and not to the totality of all nations in all parts of the world. Because of the mention of apostles and evangelists in Ephesians 4:11, numerical growth is probably also implied. However, the introduction of the body metaphor implies the notion of the qualitative development of the church as an organism from within. It should be noted that Paul uses "we all", and not "each one of us", to counter possible over-individualisation as well as underscore the corporate sense of spiritual maturity (cf. Best 1998:377). Although the verb καταντάω generally means to meet against, arrive, attain, come, and arriving completely at (cf. Foulkes 1989:129), in this context it refers to attaining or arriving at a particular final discernible point, state or destination (Hodge 1994:139).

3.2 Unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God

One of the elements of the final destination of the church is that the church grows towards unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God. This is unity of a particular kind, one that is to be attained. There may be other kinds of unity, but ultimately, the church is to attain unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God. Since faith and knowledge are not equivalent, the rendition would not be unity of faith that is the knowledge of the Son of God. Faith is not mere cognition, which knowledge is, but recognition, comprehending all the elements of that state of mind of which the Son of God is the object, including the apprehension of his glory, the appropriation of his love, and confidence in, and devotion to him (Hodge 1994:140).

From the construction of εις τήν ενότητα της πίστεως και της έπιγνώσεως του υίου του θεου, it is clear that unity, in this instance, is not the unity between faith and knowledge, because the construction presents the unity of faith and the unity of the knowledge of the Son of God - two separate kinds of unity. The expression του υίου του θεου suggests that the Son of God is the only object of knowledge, because of the article "the".

The "one faith" in Ephesians 4:6, which Christians already have, is not the same as the unity of the faith in Ephesians 4:13. "One faith" may simply mean one creed, one confession of faith, or one articulation of a set of beliefs. There is "one faith". "Unity of faith", in this instance, does not refer to unity created by faith or resulting from common faith, not even to unity as that which lies in faith. As Best (1998: 400) suggests, faith ranges in meaning between expressing the response to what God has done and the objective content of what is believed. The association of faith and knowledge, as well as the role of instruction and references to steadfastness in the face of false teaching suggest that Paul has in mind faith as objective content, or the objective truths, which the person has been taught and knowledge of this body of truths. If this is true, "faith" in the context of Ephesians 4:13 would refer to a body of doctrine.

It is noted that "unity of the faith" is in relation to the destination of all Christians. Therefore, Christians are to strive towards holding to the same body of doctrine,5 in a similar or common fashion. This would include holding to the same creedal convictions,6 even including the knowledge of the Son of God. However, the context does not limit or even suggest that unity of the faith is to be unity of faith in terms of only what Christians know and accept about the Son of God. There is "one faith", but the goal of Christian endeavour is unity of this faith, to fully appropriate the oneness of faith. The idea, in this instance, is of the whole church moving towards the appropriation of all that is contained in its one faith. Thus, Christians are to continuously mature until they are all found to share a single faith and acknowledge a common bond.

There are several possibilities regarding the meaning of "the unity of the knowledge of the Son of God". Obviously, "the knowledge of the Son of God" cannot be the knowledge that the Son of God possesses or the knowledge that the Son of God has of the church. "The knowledge of the Son of God" could refer to the content of the faith, not simply the knowledge about the Son of God. Thus, "the unity of the knowledge of the Son of God" would refer to the unified content of what is known about the Son of God. As such, attaining the unity of the knowledge of the Son of God then means appropriating all that is involved in the salvation through Christ and the full knowledge of what is given in him. Christians may possess the knowledge of the Son of God in a variety of ways and degrees. Paul's teaching, in this instance, is that Christians attain a "oneness" with regard to the knowledge of the Son of God that they possess both in the content of the knowledge and in the manner in which they all together possess. Unlike what Paul writes earlier, when such knowledge of the Son of God was viewed as a gift to be received by the recipients (cf. Eph. 1:17-19, 3:16-19), it is now also viewed as a goal to strive for and attain.

Although this is the only place in Ephesians where the title "the Son of God" occurs, it should not be construed to mean that divergent views about Christ's sonship were troubling the recipients. In any case, there is nothing to suggest that Paul is attacking any inappropriate notions with regard to the sonship of Christ to God, since he mentions nothing about the nature of true knowledge (of the Son of God). In this instance, "knowledge" refers to that which is known, or to that there is to know, about the Son of God; complete knowledge of the Son of God should then mean the full comprehension of the exalted Son of God (cf. Liefield 1997:108). The unity of this knowledge then may require a progressive movement toward full appropriation of the knowledge of Christ, which will result in a personal and living relationship with Christ. By implication then, the church must strive to come to this knowledge, which would exclude all diversity. With the knowledge of the Son of God, or fully knowing the Son of God, it then becomes possible for the church to have stability in sound knowledge, the ability to resist wrong influence, the ability and orientation to distinguish truth from falsehood, and the ability and readiness to follow the truth and reject wickedness.

3.3 Unto a perfect man

The use of the word for man, which is the masculine noun for a male person, άνήρ, rather than the inclusive ανθρωπος, "human being", should be noted. Since Paul uses ανθρωπος when he refers to the human being without sexual orientation (cf., for example, Eph. 4:2, 15; 4:22-24), his use of ανήρ must be viewed as deliberate. Άνήρ is the adult male, a full-grown man, normally in the fullness of his powers. With regard to τέλειον, some (cf., for example, Hodge 1964:234) are of the opinion that it refers, in this instance, to age, rather than to stature, supposedly because τέλειον in the preceding clause means mature or adult, hence in reference to age rather than to stature; νήπιος in the following verse means a child, in terms of age, and not in terms of size. To others (for example, O"Brien 1999:308), stature, rather than age, is preferred, in this instance, for the imagery of fullness, since fullness is supposedly more naturally suited to spatial categories. Τέλειον is also considered to have the nuance of mature rather than perfect. Yet to others (for example, Muddiman 2001:204), the meaning of τέλειον is to be generated from the "full stature of Christ", and so the mature manhood refers to the cosmic Christ.

Although τέλειον has this wide range of meanings, it seems to refer, in this clearly ethical context, to maturity, completeness and perfection. Therefore, since in the context of Ephesians 4:13 τέλειον modifies άνήρ, it should be translated as the "perfect man" or "man who is complete" or "full-grown adult male", presuming of course that the full-grown adult male correspondingly reflects the desired attributes. It follows that, when used of a man, τέλειον means an adult, one who has reached the end of one's process of development as a man; when used in reference to a Christian, τέλειον would mean one who has reached the end of one's development as a Christian, and when used in reference to the church, it would mean that the church has reached the end of her development and stands complete and in complete conformity to Christ. Since Paul is writing in relation to the church, τέλειον is, in this instance, in reference to the church. It means, therefore, that in its complete state, the church is viewed as a corporate entity, as "we all" are to move toward "the mature person", not "mature people", and as Robinson (1971:101) aptly puts it, the plural is in the lower stage of maturity only, if it is maturity in the first place.

3.4 Unto the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ

The word "measure" (μέτρον) occurs in the Bible in a variety of renditions. In this context, "measure" may not refer to an instrument that measures size or quantity, nor to a step or definite part of a progressive course or policy, a means to an end, or an act designed for the accomplishment of an object (cf. Encyclopaedia Britannica 1971:26). Since in this context μέτρον is a noun, it may not refer to ascertaining by using a measuring instrument or to compute the extent, quantity, dimensions, or capacity of something. In this instance, μέτρον refers to being of a certain size or quantity, or to having a certain length, breadth, thickness, or intensity, or having a certain capacity, according to a defined standard. Thus, μέτρον refers to a standard of dimension; a fixed unit of quantity or extent; an extent or quantity in the fractions or multiples of which anything is estimated and stated; hence, a rule whereby anything is adjusted or judged. It also refers to the dimensions or capacity, size or extent of something, according to some standard. In this case, the standard is Christ himself (cf. Stott 1979:170).

Given the ambiguity of ηλικία, its meaning must be determined from the context. Since the context contains the contrast between children and adults, ηλικία could be validly interpreted as age, as a further part of this contrast and as an explanation of what was meant by "mature person". Age is favoured by the general context because of the notion of maturity, since adults are more mature than children. The term νήπιοι in Ephesians 4:14 would contrast favourably with the idea of maturity. Filling and building are metaphors of space and from these the idea of size is appropriate, after μέτρον. From this discussion, it appears that ηλικία is used with both age and size in mind and, therefore, its interpretation would require a consideration of both age and size (cf. Lloyd-Jones 1980:211). Age and size together constitute maturity, or immaturity for a young age and small size.

The πληρώματος of Christ is perhaps the most ambiguous word in Ephesians 4:13. The πληρώματος of Christ can mean that which fills him, or that which he fills. The "measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ" may also be interpreted as the full measure of the complete stature, or maturity, of the fulfilled Christ (cf. Robinson 1971:101; Hodge 1994:141), but this would raise serious theological questions such as whether there was a point in time when Christ was not fulfilled. The "fullness of Christ" could mean the "plenitude of excellence", which Christ possesses, or which he bestows (Hodge 1994:141). Words related to πλήρωμα include the verb πληρόω, "I fill", signifying that which is or has been filled; and that which fills or with which a thing is filled; it would then signify "fullness", or "a fulfilling". That being the case, it would also refer to a state of being full, abundant, or complete. In the New Testament, outside the Gospels,7 only Paul uses the term πλήρωμα twelve times, four of which are to be found in Ephesians.8 Prior to Ephesians 4:13, Paul writes, "unto a dispensation of the fullness of the times" (Eph. 1:10); "which is his body, the fullness of him who fills everything in every way" (Eph. 1:23),9 and "that you may be filled to the measure of all the fullness of God" (Eph. 3:19).

In Ephesians, Paul uses πλήρωμα sometimes with reference to Christ, as Christ is himself to "fulfil" all things in heaven and on earth (cf. Eph. 4:10) and at other times with reference to the church and the individual Christian. The "fullness of Christ" in Ephesians 4:13 is perhaps not to be separated from "the church, which is his body, the fullness of him who fills all in all" in Ephesians, that Christ is being fulfilled, and finds his fullness in the church. In Colossians (cf. Col. 1:19; 2:9), "the fullness" of God in Christ is contrasted with the angel-powers that were supposedly intermediate between God and the world. The false teachers at Colossae seem to have employed the term "fullness" to signify the entire series of angels, which filled the space and the interval between a holy God and a world of matter, which was conceived of as essentially and necessarily evil. In a contra-correction to the Colossian false teaching regarding "the fullness", Paul shows that in Christ dwells all the fullness of the Godhead bodily.10

The "fullness of Christ", in the context of Ephesians 4:13, therefore refers to the church attaining the standard or the level of a church that is filled with Christ, or which Christ fills, as well as the church attaining complete conformity to Christ, and all Christians reaching this high standard. The measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ means attaining the perfection of faith, and the essence of that is to hold fast to Christ as true and perfect God and to mature unto a full understanding of the divinity of the Son of God. Since, in this context, πλήρωμα more naturally also has spatial connotations, the standard for the believers" attainment can be taken to be the mature proportions that befit the church as the fullness of Christ. As such, the church has by faith the full possession of all that Christ has to impart, particularly his moral, intellectual and spiritual perfection.

Whereas Ephesians 4:16 suggests that the goal is the complete growth of the body of Christ, each of the three phrases in Ephesians 4:13 incorporates a reference to Christ, involving an understanding of Christ, and a relationship with him. Although the use of the word μέχρι suggests a time frame for the attainment of the goal, Paul does not suggest when the goal would be attained. The full maturity to be attained is more specifically defined by its measure, namely the full stature of Christ. The clause "so that we may no longer be children ..." provides a general comment on the current state of the readers, but also indicates what should take place if genuine progress towards the final destination is to be made. With the building up and bringing to completion of the church, immaturity and instability can increasingly be left behind, and the church will increasingly move into a mature state (cf. Foulkes 1976:122; Stott 1979:140; MacArthur1986:157; Hodge 1994:141).

4. DEDUCING THE GOAL OF MATURITY

From the foregoing analysis, and according to Ephesians 4:13, maturity means all Christians together as the church, ultimately attaining a state of oneness of the contents of faith and acceptance and possession of complete, correct and full understanding of Christ, and being so completely filled with Christ's essence in his glorified state that the church, in full conformity with Christ, is an accurate full physical manifestation of Christ in the world. As such, maturity has the following four dimensions:

- Essence: Maturity refers to a specific final and discernible destination; arrival at that destination is supposed to be for all Christians who increasingly become "one" as they approach that destination.

- Means of attainment: Maturity is a sequel of the ministry participation, variously, of all Christians as started off and continuously equipped and guided by the apostles, evangelists, prophets, pastors and teachers Christ has appointed and has given as gifts to the church. Thus, unlike salvation, which is by divine grace alone (cf. Eph. 2:8-10; Rom. 3:2130), maturity is a product of salvation, and requires sustained human effort to move towards its attainment.

- Point of attainment: In theory, the point for attaining maturity is when the whole church will have attained the goal. The church is to grow in order to become an appropriate body, befitting as well as worthy of the Head, Christ. Practically, however, each time there is a new convert to the Christian faith who will need to be discipled, the configuration returns to a state of spiritual immaturity, and as new believers continue to join the church, the duration of attaining the goal of ultimate maturity is at consummation.

- Indicators of progression towards maturity: Indicators of maturity are an important dimension of maturity. They include the corporate stability and constancy in the truth; the ability to discern error and reject or correct it; the ability and predisposition to speak the truth in love, and the meaningful participation of all members through effective use of their individual gifts. Unity is a reality that occurs by default when there is maturity. This means that maturity will effect unity, but not vice versa.

5. THE NECESSITY OF MATURITY

A key question may arise from the identified meaning of maturity. Is maturity simply something nice, good or important, or necessary for the church? Is Paul merely recommending or inviting the church, to consider and make a decision as to whether or not to grow towards such maturity? This section examines the implications of the meaning of maturity in the context of Ephesians 4:13-16.

5.1 Lack of maturity is dangerous for church members

It is apparent that maturity is imperative. Without it, Christians will not stop being "infants". "So that" preceding "we will be no longer children" (Eph. 4:14) shows the consequences related to lack of maturity. The weight of the use of the "children" imagery and its elaboration suggest a call for the church to grow towards maturity. In this context, being an infant is a negative image.11 The harsh reality of being in that state is compared to a ship without a rudder and thus helplessly tossed to and fro by the waves and driven about by every wind. Like children, they will be volatile in their beliefs, unstable, foolish and incapable of understanding the truth.

The contrast between "the mature manhood" in Ephesians 4:13 and the term "children" in Ephesians 4:14 suggests that the ignorance and instability of the "children" stand in contradistinction to the knowledge of the mature adult. The term κλυδωνιξόμενοι suggests rough waters, and the passive participle of the cognate verb means tossed by waves; the same term is used in Luke 8:24 and in James 1:6. Thus, an immature church, that will, in fact, be immature Christians will be entirely at the mercy of the waves and the wind that know no mercy. In addition, the state of confusion and lack of direction contrast strongly with the goal-oriented language of Ephesians 4:13. This implies that immature Christians are endangered and prone to the perversion of false instruction with adverse repercussions for faith living. This means that immaturity on the part of Christians cannot be treated as a neutral state that will be outgrown in due course. On the one hand, lack of maturity will mean the recipients individually remain children, unable to discern and reject or oppose dangerous false teachings. On the other hand, by implication, it is only with such maturity that Christians will no longer possess or display the negative characteristics of being children.

5.2 False teachers and their false teachings and methods are difficult to discern and resist

Paul's description of false teaching, false teachers and the methods they use also reflects the imperative of spiritual maturity. In the context of Ephesians 4:14, Christians can expect to face false teachings. "Every wind of doctrine" suggests different kinds of teaching that stand over against the unity of faith and knowledge, which the recipients must attain. It is likely that these different kinds of teachings would include the various religious philosophies that threatened to undermine the Gospel, not simply the teaching within the church.12 Because Paul does not give specifics of "every wind of doctrine" (παντί άνέμω της διδασκαλίας), it may suggest that he is talking about the general dangers that were a hindrance to those not firmly grounded in the faith. Unable to come to settled convictions or to evaluate various forms of teaching, immature Christians would be easy prey to every new theological fashion or trend.

That the false teachers are intentional and ready to do everything possible to deceive and mislead signifies the malicious deception whereby the false teachers seek to lead the unstable astray. In the metaphor of the sea and its storms, false teachings are described as having the potential to destroy, to derail, or to uproot. The singular διδασκαλίας with the definite article implies a specific false Christian teaching, but the qualification παντί with άνέμω indicates a variety of winds and, therefore, a variety of teachings. Since the remainder of the Epistle is mainly devoted to ethical instruction, the false teaching may also be about behaviour, over and above heretical doctrinal teaching.

Paul attributes the departure from the truth to the false teachers, who are, by methodology and tendency, cunning and deceitful. False teachers are not simply uninformed or incorrect teachers; therefore, they can never be innocent. In the phrase έν τη κυβεία των ανθρώπων, έν πανουργία προς τήν μεθοδείαν, Paul uses the term κυβεία ("cunning") and the preposition προς ("according to"), as he is talking about cunning according to the craft which error uses. The same word is used to describe the Serpent's act when he deceived Eve (cf. 2 Cor. 11:3; Gen. 3:1-9). Satan's machinations have a method; his aim is to mislead. Thus, behind the false teachings are not simply evil men and women who pursue their unscrupulous goals with a scheming that produces error - πλάνη - deceit, false teaching - standing against apostolic practice and the truth. Rather, behind the false teachers is a supernatural, evil power that seeks to deceive Christians.

The expression έν τη κυβεία των ανθρώπων indicates the direction of the tendency, that is, this cunning is designed to seduce. The term μεθοδείαν occurs only in Ephesians 4:14 (in Eph. 6:11, it is used in the plural, μεθοδείας, to refer to the wiles of the devil) and can be defined as the "well-thought-out, methodical art of leading astray" (cf., for example, Lincoln 1990:259; Best 1998:406; Muddiman 2001:207), or human trickery (Hendriksen 1967:202). The term is derived from μεθοδεύω, which essentially means to track a person down, as a wild animal would its prey. Foulkes (1989:350) captures the broader notion of the "tossing winds". In Paul's mind, the false doctrines constitute a general evil atmosphere where current wrong doctrines exert their force on Christians. This means that maturity is simply a requisite for the church.

6. CONCLUSION

In interpreting Ephesians 4:13-16, the goal of maturity has been determined. Maturity refers to a specific final and discernible destination of all Christians who increasingly become "one" as they approach that destination. Therefore, maturity requires sustained human effort to be moving towards the goal. Although in theory, the point for attaining maturity is anytime when the whole church will have reached the destination, practically, as each time there is a new convert to the Christian faith, the configuration changes back to a state of immaturity. This means that, as new converts continue to join the church, the ultimate maturity will be realised at consummation.

Micro-structural analysis and interpretation have also shown that spiritual maturity is imperative for the church, because without such maturity the church will fall prey to false and wrong doctrinal teachings by persons from within and from outside the church who are both intentional about and highly skilful in scheming to lead Christians astray. More research is needed in the sphere of maturity to inform efforts to continue building up Christians so that they can be the "salt of the earth" and the "light of the world" (cf. Matt. 5:13, 14). Only spiritually mature Christians will be able to have a positive influence on society and make the world a better and wholesome place. Similarly, only spiritually mature Christians, as light of the world, will be able to illuminate and give guidance to society.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Best, E. 1998. A critical and exegetical commentary on Ephesians. London: T. & T. Clark. The International Critical Commentary on the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments. [ Links ]

Boice, J.M. 2007. Ephesians: An expository commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. [ Links ]

Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1965. Volume 9. Chicago, ILL: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. [ Links ]

Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1971. Volume 15. Chicago, ILL: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. [ Links ]

Foulkes, F. 1976. The Epistle of Paul to the Ephesians: An introduction and commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. Tyndale New Testament Commentaries. [ Links ]

_______. 1989. Ephesians. Revised edition. Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press. Tyndale New Testament Commentaries. [ Links ]

Guthrie, D. 1961. The Pauline Epistles: New Testament introduction. London: Tyndale Press. [ Links ]

Hendriksen, W. 1967. Ephesians. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth. New Testament Commentary. [ Links ]

Hodge, O. 1964. A Commentary on the Epistle to the Ephesians. London: The Burner of Truth Trust. [ Links ]

_______. 1994. Ephesians. Wheaton, ILL: Crossway Books. The Crossway Classic Commentaries. [ Links ]

Hoehner, H.W. 2002. Ephesians: An exegetical commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic. Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament. [ Links ]

MacArthur, J. 1986. New Testament commentaries: Ephesians. Chicago, ILL: Moody Press. [ Links ]

Mbennah, E.D. 2009. The mature church: A rhetorical-critical study of Ephesians 4:1-16 and its implications for the Anglican Church in Tanzania. Unpublished PhD. thesis. Potchefstroom, South Africa: North-West University. [ Links ]

Liefield, W.L. 1997. Ephesians. Downers Grove, ILL: Inter-Varsity Press. The IVP New Testament Commentary Series. [ Links ]

Lincoln, A. 1990. Ephesians. Dallas, TX: Word Books Publishers. Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 42. [ Links ]

Lloyd-Jones, D.M. 1980. Christian unity: An exposition of Ephesians 4:1-16. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House. [ Links ]

Muddiman, J. 2001 . A commentary on the Epistle to the Ephesians. London: Continuum. Black's New Testament Commentaries. [ Links ]

Schnackenburg, R. 1991. The Epistle to the Ephesians. Translated by H. Heron. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

Stott, J.R.W. 1979. The message of Ephesians: God's new society. Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press. The Bible Speaks Today. [ Links ]

1 Some post-19-century scholars reject the traditional view of the Pauline authorship of Ephesians in favour of pseudepigraphy or a combination of authenticity and pseudepigraphy. But the arguments against Pauline authorship are inconclusive. A Paulinist imitator, had there been one, would have produced a more stilted summary of Paul's doctrines and themes, which is not the case. As Guthrie (1961:127, 128) observes, "When all the objections are carefully considered it will be seen that the weight of evidence is inadequate to overthrow the overwhelming external attestation to Pauline authorship, and the Epistle's own claims ... To maintain that the Paulinist out of his sheer love for Paul and through his own self-effacement composed the letter, attributed it to Paul and found an astonishing and immediate readiness on the part of the Church to recognize it as such is considerably less credible than the simple alternative of regarding it as Paul's own work." There is ample evidence of universal acceptance of Pauline authorship from ancient until modern times. Marcion in AD 140 included it in his canon as Pauline and the Pauline authorship was undisputed, except that Marcion retitled it as "Laodiceans". In the Moratorium Canon (AD 180), Ephesians was included under the letters of Paul and forms part of the Pauline Epistles in the earliest evidence for the Latin and Syriac versions and many other ancient manuscripts. It is my proposition, therefore, that when the fullest consideration is given to the basic facts, the Pauline authorship of the Ephesians is sustained.

2 Although the books of the New Testament were written with specific first readers in mind and, therefore, the human authors would have had specific purposes such as addressing specific issues that the first readers faced, the overall purposes of the books of the New Testament are applicable to all people of all time and place, to "hear what the Spirit is saying". Therefore, what is at issue is not the relevance of New Testament books such as the Epistle to the Ephesians, but rather the task of interpretation and application of such texts.

3 Among them are Stott (1979); Lloyd-Jones (1980); Lincoln (1990); Schnackenburg (1991); Best (1998); O"Brien (1999), Muddiman (2001), and Hoehner (2002).

4 The purpose of the analysis of thought structure on the micro-level is to examine how the syntactical units of the pericope Ephesians 4:1-16 are related to one another, in order to establish the syntactical function of Ephesians 4:13. For an explanation of the theory and procedure of thought structure and syntactical analysis, cf. Van Rensburg (1981).

5 Objectively, faith denotes that which is believed or that to which assent and affirmation are given. Subjectively, faith refers to the disposition to believe, assent or affirm or to the act of believing or affirming. In the New Testament, all uses of "faith" ultimately have to do with Jesus Christ. The principal areas reflected in relation to Jesus Christ as aspects of faith are: his unique kinship with God the Father (Matt. 16:13-20); his person and work as the fulfilment of scriptural promises of a Messiah and a messianic kingdom (Matt. 11-2-6); his power over nature and over evil (Lk. 8:26-39); his moral and spiritual lordship over humankind through his teachings, his person and his atoning work on the Cross (Matt. 28:16-20), and the reality of redemption from sin and victory over death in, and through him (1 Cor. 15:12-28).

6 Similar to what would be called "rule of faith" or "canon of truth", which means the central points of Christian teaching as articulated by the apostles, namely that Christ was killed, raised from the dead, and exalted; that these things happened in fulfilment of Old Testament prophecies and were attested by the witness of the apostles; that God now is offering salvation to those who believe and repent and are baptised, and that, ultimately, Jesus Christ will be the judge of all.

7 In the Gospels, it occurs in both Matthew 9:16 and Mark 2:21, where it means "the fullness", that by which a gap or rent is filled up, as in patching a torn garment; in Mark 6:43, "they took up fragments, the fullness of twelve baskets"; in Mark 8:20, "the fullness of how many baskets of fragments did ye take up?", and John 1:16, "out of his fullness we all received".

8 Outside of Ephesians, Paul uses πλήρωμα in Romans 11:12, "If their loss (is) the riches of the Gentiles; how much more their fullness?", "fullness" of Israel, in this instance, referring to the nation of Israel being received by God to a participation in all the benefits of Christ's salvation; Romans 11:25, "A hardening hath befallen Israel, until the fullness of the Gentiles be come in"; Romans 13:10, "love is the fulfilment (the fulfilling) of the law"; that here "fulfilment meaning a complete filling up of what the law requires; Romans 15:29, "I shall come in the fullness of the blessing of Christ"; 1 Corinthians 10:26, "The earth is the Lord"s, and the fullness thereof"; Galatians 4:4, "when the fullness of the time came", meaning that portion of time whereby the longer antecedent period is completed; Colossians 1:19, "In him should all the fullness dwell", and Colossians 2:9, "For him the whole fullness of deity bodily" (RSV).

9 That means the church is the fullness of Christ; the body of believers filled with the presence, power, agency and riches of Christ.

10 I suppose the fullness of the Godhead (Col. 2:9; 3:19) is the totality of the divine powers and attributes as eternal, infinite, unchangeable in existence, in knowledge, in wisdom, in power, in holiness, in goodness, in truth, and in love. The fullness of the nature of God would be his life, light, and love, and this has its permanent dwelling in Christ. This implies that the fullness of Christ is the timeless and eternal inhabitation of the fullness of the Godhead from the Father to the Son.

11 Νήπιοι could be used positively to symbolise simplicity and innocence, cleanness from adult decadence (cf., for example, 1Pet. 2:2; Matt. 11:25; Matt. 18:3; Matt. 21:16; Lk. 10:21). Negatively, as in this context, children are pictured as unstable, lacking in direction, susceptible to deception, and open to manipulation. This is being childish. God is pleased with the child-like, the innocent ones. Therefore, a distinction is to be made between being child-like and being childish.

12 Best (1998: 405) suggests that, as Christians were under continual pressure from other Christians in respect of what was true teaching, each teacher claiming the truth in what he was teaching, and that because a variety of teaching and doctrinal novelty would have been normal during this stage of the church, Paul would in this regard be referring to the variety of teaching within the church rather than false philosophies and theologies entering it from outside. This view is, however, debatable, because it fails to take cognisance of the force of the adjective "every" in the phrase "every wind of teaching", which suggests any and all kinds of teaching. It is better, therefore, to take this as a reference to the false teaching in the guise of the various religious philosophies that threatened to assimilate, and thereby dilute or undermine the Gospel, both from within and from beyond the church.