Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.36 n.1 Bloemfontein Jun. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v36i1.6

ARTICLE

"Anatheism" within the framework of theodicy: From theistic thinking to theopaschitic thinking in a pastoral hermeneutics

D.J. Louw

Faculty of Theology, Stellenbosch University, 171 Dorp Street, Stellenbosch. E-mail: djl@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The Syrian and refugee crises, the violent radicalisation in Europe, and global xenophobia stir up anew the link between the human quest for meaning and hope within the realm of human misery and destructive acts of severe evil. The article focuses on the problem of theodicy and its link to God images. It discusses both inclusive and exclusive approaches to the theodicy issue, and proposes a paradigm shift from threat power to intimate, vulnerable power. A diagram is designed in order to identify different metaphors for God in pastoral caregiving. With reference to a pastoral approach, lamentation is viewed as an appropriate variant for theodicy. In the attempt to return to 'God after God' (anatheism), lamentation could help reinterpret the hesed of God in terms of our human predicament of 'undeserved suffering'.

Keywords: Theodicy, Theopaschitic theology, Power of God, Lament, Meaning in suffering, Anatheism

Trefwoorde: Teodisee, Teopasgitiese teologie, Mag van God, Klag, Sin in lyding, Anateïsme

1. INTRODUCTION

The attack on innocent civilians in France on Friday night, 13 November 2015, left human beings all over the globe speechless,2 raising anew the issue of violence and evil within the context of a fairly civilised and democratic European society. Paris has become the epitome of a global networking of fear and unqualified anxiety. There is no longer a safe place on earth. The global village has become the playground of demonic and evil forces.

The discovery of a potential attack on vulnerable human beings (tourists) at Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin (February 2016) raised many negative reactions. According to Casdorff (2016:1), these kinds of events are questioning the current Willkommenskultur in Germany and fuel radical reactions and aggressive attitudes (Sorgen bereiten Aggressivität).3

The United States' President Barack Obama referred to the assault by gunmen and bombers that left at least 129 dead in the French capital:

This is an attack not just on Paris, it's an attack not just on the people of France, but this is an attack on all of humanity and the universal values that we share (Faulconbridge & Young 2015:1).

Obama immediately labelled the attackers as the perpetrators: "We stand in solidarity with them (France) in hunting down the perpetrators of this crime and bringing them to justice" (Reuters 2015:11). Obama called the Paris attacks an outrageous attempt to terrorise civilians.

According to Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan,

[w]e are confronted with collective terrorism activity around the world as terrorism does not recognise any religion, any race, any nation or any country (Reuters 2015:11).

This is the reason why Obama is convinced that the terrible attacks and the killing of innocent people based on a twisted ideology is an attack not on France, not on Turkey, but it is an attack on the civilised world (Reuters 2015:11); it is a global4 threat to the meaning and significance of our being human.

On the crisis in the Middle East and Syria, United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon is convinced that the horizon of hope in 2014 is bleak and dark. It seems as if the world is falling apart; there is an upheaval of crises, and the threat of the Ebola virus is causing concern and anxiety. He warns of 'turbulence' ahead, with wars, refugees, disease and climate change: "This year, the horizon of hope is darkened" (Ki-Moon 2014). On 17 October 2015, after meeting with families of refugees at a reception centre in Italy, Rome, Ki-moon (2015) stated that the global community has to "stand with people who do not have any means" and provide basic necessities such as education and sanitation.

In his response at the United Nations to the Syrian crisis, President Obama (2014) stated emphatically:

The world is on the crossroad between war and peace. Mr. Secretary General, fellow delegates, ladies and gentlemen: We come together at a crossroads between war and peace; between disorder and integration; between fear and hope.

How should one reintroduce hope when the future seems bleak? How does our understanding of the Christian God fit into this picture where people oscillate between war and peace, and where we are challenged to stand with people who do not have any means?5

It is within this global context of fear and paranoia that I want to probe into the question of theodicy and the impact of a global threat on existing God images and the human quest for meaning. Radicalisation in Europe questions current political systems as well as core issues in Christian spirituality (Casdorff 2016:1). Violent reactions stir existing paradigms regarding the meaning and destiny of humankind.

2. THE 21st CENTURY: STRUGGLING TO RECOVER A SENSE OF MEANING?

In terms of his experiences in the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II, Frankl (1975:87) became aware of an existential vacuum that influences one's focus on values. Hopelessness and meaninglessness create an existential vacuum and lead to what he calls "noogenic neurosis". Noogenic neurosis does not result from a clash between impulses and instincts, but from moral conflicts and the burning issue of evil in this world that affect one's basic will to find meaning.

Frankl (1969:102) asserts:

It should be clear, then, that even under concentration camp conditions psychotherapy or mental hygiene could not possibly be effective unless directed toward the crucial factor of helping the mind find some goal in the future to hold on to. For healthy living, is living with an eye to the future.

For many of us the thought of the future is a cause for irritation rather than optimism, as if we had enough of new things, and wish only for the long sleep that rounds the edges of our lives (De Bernières 2005:1).

Maddi (2012:69) points out that, besides a kind of ontological anxiety about our future, the most severe existential sickness is vegetativeness. At a cognitive level, those who suffer from vegetativeness cannot find anything they are doing or can imagine doing that seems interesting or worthwhile.

At the emotional level, vegetativeness involves a continuing state of apathy and boredom, punctuated by periods of depression that becomes less frequent as the disorder is prolonged (Maddi 2012:69).

The questions where to and wherefore point to what sociologist Berger (1992:121) calls the quest for "signals of transcendence". We each have a desire, or need, for something greater than ourselves, for some bigger purpose or meaning in life.

In openness to the signals of transcendence the true proportions of our experience are rediscovered. This is the comic relief of redemption; it makes it possible for us to laugh and to play with a new fullness (Berger 1992:121).

Signals of transcendence create spiritual spaces for processes of hoping when life seems to be merely the tragedy of a cul de sac.

Wong (2012:19) is convinced that the 21st century may be called a century of meaning, in which people are struggling to recover a sense of meaning and purpose in the midst of international terrorism and the global financial meltdown.

The creation of a new world order and a more cooperative and humane society will demand a grassroots campaign to educate people about the importance of responsible and purposeful living. (Wong 2012:19).

The quest for meaning in suffering is, without any doubt, still a most relevant and poignant question in the 21st century. Despite the miracle of the Internet and Big Data, the quality and meaning of human relationships still seem to be under severe pressure. In her new book, MIT researcher Turkle, argues that relying too much on virtual messaging is killing our human relationships (Docterman 2015:17).

Internet and interviews with Internet users indicate the wish for a kind of utopian condition of enhanced, qualitative livelihood; this even reveals the birth of a new "electronic frontier" (Dawson 2004:8) wherein new possibilities are opened for the so-called "Virtual Community". According to Rheingold (in Dawson 2004:81), virtual communities are social aggregations that emerge from the Internet when people continue, in public discussions established over a longer period of time, with sufficient human feeling, to form webs of personal relationships in cyberspace.Han (2013:24) mentions that the Internet can also become a hiding place wherein not multitude, but solitude shapes our new cyber society. The system of sameness can become the "hell of sameness", creating a kind of instant immediacy of life events (Han 2012:6). He even calls the Internet the new messiah of networking ("Messianismus der Vernetzung") (Han 2013:65). The point in Han's analyses is that the so-called transparency of the Internet does consider the spiritual dynamics of the human soul and its connection to the realm of suffering and grief ("Menschliche Geist als Schmerzgeburt") (Han 2013:12).

Although the cyberspace of virtual reality is, for many people, a new kind of meaning-giving, meaning implies much more than virtual networking. In this regard, Han (2013:17) opines that the Internet brings about a new mode of suffering, namely a loss of direction, purposefulness and direction.6 The artificial nature of online faces creates a kind of "soulful pornography" (Han 2013:8-9), when transparency of the soul means the immediate contact between image and seeing the reality of our being human is exposed to a kind of cyber abuse. Unlike a machine, the human soul is not transparent; otherwise, we would die from spiritual burnout; total transparency equals death (Han 2013:8-10). The Internet cannot ease out ambivalence, paradox, human vulnerability, and the reality of evil.

The current Syrian and refugee crises elicit an acute awareness that human life is under severe threat (Vick 2015:25-26). The suffering of desperate, vulnerable women and children crossing the Mediterranean Sea underlies the reality of evil in this world.

The question arises as to how theology should respond to the crisis of dislocation and the misery of vulnerable children and women. Should we revisit the traditional attempts in both philosophy and theology to link God in a causative way to suffering and meaninglessness? Does the philosophical stance of traditional theodicy suffice or should we move from an explanatory model in theologizing to a more relational and compassionate approach?

3. UNDESERVED SUFFERING: THEODICY AND THE QUEST FOR CAUSALITY

The notion of evil is indeed complex. For example, kakos and poneros in the New Testament express shortcomings or inferiority as being linked to something bad; it has ethically negative and religiously destructive connotations. Evil includes both wickedness and actions that cause damage and harm (Achilles 1975:563).

Theodicy (theos dike) means a justification of God in the light of evil and suffering. It is a human attempt to justify God's goodness and his handling of affairs. In pastoral care, one should accept the fact that some form of theodicy inevitably emerges whenever one attempts to articulate one's image of God and test this in the context of life's concrete realities. Theodicy,7 strictly conceived, attempts to show that Christians can believe simultaneously and with logical consistency: God is omnipotent and omnibenevolent, and evil is real. Therefore, theodicy is an attempt to reconcile belief in the goodness and power of God with the fact of evil in the world (Sparn 1980). The underlying presupposition then is that there is a solution and that God's power is both a violent force that determines all, and a system of control that can prevent all evil. The theological problem is whether or not one can hold simultaneously that God is omnipotent, omnibenevolent and that evil is a real threat to being human, without contradiction?

The following questions (Inbody 1997:28) summarise the dilemma of theodicy: Does God provide evil (then He is omnipotent, but not good)? Does He not provide evil (then He is good and loving, but not omnipotent)? This dilemma creates a tension between God's omnipotence and his omni-benevolence. The problem in this dilemma is that theology presupposes a schism between God's omnipotence and his goodness (love). These have often been viewed as two different opposing attributes. Because of this tension, two main tendencies can be identified within different theories in an attempt to explain the relationship between God and suffering (Van Beek 1982).

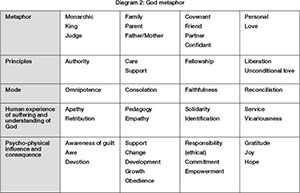

In order to systematize the different traditions and viewpoints about theodicy, one can generally distinguish between an inclusive and an exclusive approach (Louw 2015:303-313).

-

In an inclusive approach, theologians endeavour to connect God to evil in order to safeguard his control: God is almighty and determines everything in life. All events are somehow linked to God's will and providence.

-

In an exclusive approach, theologians react against a static model that portrays God in an unsympathetic manner. They intend to stress God's pathos as an indication of his compassion and even of his protest against all forms of evil and suffering. They want to exclude God from being the cause of all human suffering. Therefore, God's identification with suffering indicates that He does not necessarily cause suffering. Hence, the notion of the "suffering God".

This diagram briefly outlines the main viewpoints. The danger in such an attempt is oversimplification. It is impossible to do justice to the complexity of many arguments and stances. The diagram should, therefore, be viewed as an attempt to provide a general overview in order to locate different primary approaches and theological perspectives.

3.1 Inclusive arguments (suffering: the will of God?)

Inclusive arguments mean the attempt to link God and his will to suffering and, ultimately, to the existence of evil. Thus, in order to safeguard his omnipotence, nothing on earth could happen without God's permission. If suffering could be viewed as an exponent and manifestation of evil, i.e. of the disruption of our fundamental relationships, the threat of chaos and disobedience to God's law and plan for human life, then (and this is the argument) evil cannot be an entity apart from his sovereignty. A dualism is impossible between a theistic God and evil.8

In this instance, there are three main arguments: suffering and its link to punishment and the wrath of God; suffering as a means to a higher end within a process of development or evolution, and suffering and the imperfection of creation under God's permission.

3.1.1 Suffering and evil as punishment for sin

For the believer, suffering can serve as a means of discipline in order to attain sanctification. In this view, God is not necessarily viewed as the direct origin of all suffering and sin. Sin remains against his will. Nevertheless, according to Augustine, sin is not beyond God's will and can be incorporated into his plan. Suffering, as punishment for sin, does not place human beings beyond God's will: all suffering can be traced to his will or, at least, to his permission. The believer needs to reach acquiescence under God's permissive will, in the knowledge that all questions will ultimately be answered.

3.1.2 Suffering and evil, viewed teleologically, as a process or means of attaining a higher goal (gubernatio)

All things are directed towards God's chosen purposes. In light of his ultimate purposes of creation, God even allows, to Him, unwanted negative aspects of life and sin.The stoic, monistic worldview attempts to reconcile the course of the world (fatum) with God's providence (pronoia, providential). This gives rise to a cosmodicy, a justification of the given world as an appearance and manifestation of the Divine reason. The world's imperfection is necessary in light of the coming perfection. The evil that lies concealed in affective bodily needs and matter presents a challenge to the human freedom of will. This challenge can be overcome by an apathetic lifestyle. Apathy gives rise to an ethic of patience and neutrality towards suffering in order to bring about self-sufficiency. Within this rational teleology, suffering serves as a means of bringing a person to the perfection of self-sufficiency.

According to the Irenaeus tradition, God created a world that included evil with a view to the end goal of a perfect world. Hick (1966) argues that the Fall is an essential feature of all creatureliness. Human beings are in the process of becoming perfect beings conforming to God's original purpose. Human autonomy must develop into goodness, thus necessitating the possibility of both good and evil. There is an intellectual gap between God and human beings; God affords human beings the space to grow towards perfection. Evil serves a purpose in this process: it is necessary for one's freedom and ultimate goodness. The conflict between good and evil will be resolved eschatologically in the eternal life.

3.1.3 Suffering and evil can be linked to the reality of creatureliness (imperfection)

The third perspective in an inclusive theodicy views suffering and evil as a possibility or potential that is linked to, and incorporated in the creatureliness of reality.

In a sense, Leibniz9 can be considered the father of "theodicy". According to Leibniz (1951), evil is not an absolute necessity, but a hypothetical necessity. Evil is a thought possibility of God and not an act of his will. God allows evil as a possibility (permettre),10 without processing it Himself. Evil, as a thought possibility, is a subsection of good. God, the absolute Perfection, created this world as the best possibility (optimum). One learns to recognize "the best" only by comparing it with imperfection. Thus, imperfection becomes a possibility in light of the best. God wills the best, hence the principle of metaphysical evil that serves this goal. In light of better possibilities, God wills physical evil and suffering. He thus allows moral evil as a hypothetical possibility in order to bring about greater maturity.

Leibniz's view corresponds with the views of Augustine (God allows evil in order to bring good out of it) and of Thomas Aquinas (the admission of evil leads to the good of the entire universe).

3.2 Exclusive arguments (suffering: not the will of God?)

Under inclusive theodicy, I discussed the fact that some theologians regard evil and the will of God as a paradox: He provides evil as something that He does not will. Those theodicies that tend more towards a denial of the causal relationship between God and evil emphasize God's "No" to evil even more strongly. I shall call this the "theopaschitic approach".

3.2.1 The theopaschitic approach (from authoritarian power to vulnerability)

According to this approach, God does not will evil as such, but He Himself even suffers with, or under evil in order to show his compassion (pathos). The cross of Christ (Moltmann 1972) becomes the proof that God is not unyielding and sadistic, but is deeply affected by evil. God identifies with suffering and is not apathetic towards it (Kitamori 1972). In his sympathetic involvement with suffering, God shows his compassion, thereby proclaiming that suffering is directly opposed to his will. I shall now list some of the most important proponents of theopaschitism.

-

God's weakness (Bonnhoeffer 1970).

By his suffering, God shows that He is weak, vulnerable and powerless in this world. Only Christ's weakness can help us resist suffering in an attitude of protest/resistance and surrender (Widerstand und Ergebung).

-

God's powerlessness (Sölle 1973).

Sölle objects to the sadistic image of God in traditional theodicy. She portrays Christ as God's representative, who introduces Himself as the One who suffers with human beings.

Wherever people suffer, Christ suffers, too. God suffers particularly in the social and political dimensions of suffering. God justifies Himself in political suffering. He remains powerless and is dependent on us to bring about change. As Christ's representatives, it is our task to eliminate social and political suffering.

-

God's being as an event of becoming/Gottes Sein ist im Werden (Jüngel 19672).

God's revelation of Himself is not complete. This does not mean that God Himself is incomplete, but rather that God reveals Himself as a Für-sich-sein (a Being-unto-Himself) who, in His grace, is also a Für-uns-sein (a Being-for-us). In His capacity as a Being for us, God becomes involved in the suffering of humankind. He thus becomes a suffering God for sinners in a dynamic act of revelation. In these events of God-being-for-us, God's Being is still in the process of becoming (incomplete).

-

God's forsakenness (Moltmann 1972).

God's dynamic involvement in suffering is a Trinitarian event, whose true character was revealed by the cross. In the God-forsakenness of the cross (derelictio), God is the Ganz Andere/Totally Other who does not have to be justified by humankind. On the cross, God justifies Himself as the One who pronounces justification on humankind. He does this by identifying Himself fully with human suffering and displaying solidarity with human forsakenness.

-

God's defencelessness (Berkhof 1973; Wiersinga 1972).

Wiersinga rejects the notion that suffering is punishment for sin. For him, there is no likelihood of God's justice being punitive or retaliatory. He contends that one can discount that God is the origin of suffering, or that He wills suffering and has accommodated it in His providence. The only connection between God and suffering is that He Himself suffers with us. In this instance, God reveals Himself as the defenceless God, in anticipation of the ultimate elimination of suffering. In the meantime, Christ's suffering effects a change not only in people, but also in the present reality, the ultimate goal being the termination of all suffering.

The theopaschitic approach clearly links God with suffering. The cross completes this link, revealing God as a "pathetic" being: He is the "suffering God". Feitsma (1956) calls this form of theopaschitism (redefining God's Being in terms of suffering) the ultimate expression in theology of what is meant by God's compassion.

3.2.2 Action/doing theodicy (liberation theology and the shift from metaphysics to ethics)

Parallel to the theopaschitic approach that accentuates God's pathos and not-willing of evil, there is another line of thought I call "doing theodicy", i.e. to prove God's pathos in terms of human and moral acts. These can take place in terms of severe critique, political change/transformation or acts of liberation (liberation theology). They are all geared to free humankind from all kinds of political, social and structural suffering, and especially from manifestations of suffering due to injustice and discrimination.Kant (in Sparn 1980:61) homes in on the ethical dimension by diverting theodicy away from a metaphysical-speculative level (doctrinal theodicy) to a moral-practical level. Evil is no longer viewed as a metaphysical explanatory principle on God's part, but it is part and parcel of our human freedom, responsibility and plight.

3.2.3 The futuristic theodicy (from the present to "eschatology")

In this approach, God's justification in terms of evil is postponed and redirected towards the future. The awareness that it is impossible to synthesize God's goodness with the inexplicability of suffering leads to the notion that God will ultimately negate evil and establish His future kingdom. Hedinger (1972) asserts that God will eliminate suffering in the future. In the meantime, God and human beings co-operate with each other in their struggle against suffering and, together, they will ultimately overcome it.

3.3 Theodicy: merely the quest for comprehensibility?

The problem with inclusive theodicies is that, while they attempt to save God's sovereignty, they cast a shadow on His love. In being aware that this could not be the case, the notions of God's providence and permission (God does not will evil, but allows and permits it) have been introduced in order to prevent God from becoming a passive spectator of evil. However, to declare that God does not directly will or ordain (ordinatio) evil does not free these theodicies from the question as to whether God is linked to evil (Van de Beek 1984).The following questions arise. Is God not responsible for evil? Is God a possible causative factor in suffering and the source of all evil?

The advantage of an inclusive model is that it helps us understand that, in one way or another, God is connected to evil. Evil is not a separate entity apart from the existence of God. But, and this is the burning theological question in theodicy: How should this connection be interpreted and understood?

It becomes clear that a Hellenistic cause-effect model is insufficient and leads to a very static and unsympathetic God image. Within the framework of an inclusive approach, rational speculation and the positivistic imperative for explanation can move to the point where one is forced to admit that, in the last instance, God is the author and origin of evil. Ultimately, the outcome of this argument constitutes the threat of determinism.

Taleb (2010:63) calls this kind of deterministic reasoning and the rationalistic attempt to explain (explanatory model), the causation trap. According to Taleb (2010:13), things do not develop deterministically, but through contradiction, and are intrinsically unpredictable and inexplicable.

The advantage of an exclusive model is that it comprehends God in terms of pathos. It asserts that God definitely does not want evil, as indicated in His identification and involvement with suffering. Evil is thus derivative, coming either from an external evil principle, or from the misuse of human responsibility (freedom). The problem in this approach is that, since suffering is limited to the human and creature level, one might ask whether God is ultimately limited by His own vulnerability and defencelessness? Does God's powerlessness not deliver human beings to fate? It thus appears that an exclusive model confronts human beings with the possible threat of indeterminism.

It becomes clear that theodicy can never explain suffering at a rational level. It can only describe and express the complexity of suffering and our human attempt to come to grips with our own misery. Theodicy allows theology to become conscious of the following antinomy and paradox: God can be linked to suffering, on the one hand, while He is against it, on the other. In conclusion:

-

Theodicy, as an all-encompassing explanatory and rationalistic approach, does not succeed pastorally in comforting human beings in their quest for meaning. In any event, it is difficult to arrive at a general theory regarding the origin of suffering. Suffering is not rational and rational (causal) explanations are, therefore, not sufficient. Taleb (2010:9) calls such a rational attempt the pathology of thinking, namely that the world in which we live and in which we are constantly exposed to suffering, is understandable, explainable and thus more predictable than it actually is.

-

Theodicy, as a positivistic theory or rational explanatory principle, does not offer a true perspective on who God is. Berkouwer (1975:300-305) refers to the danger that a theodicy can sometimes degenerate into a "natural theology". The problem with this type of theodicy is that it tries to argue from the perspective of the broken reality in order to attain a kind of rationalistic explanation. God's faithfulness becomes an abstraction of human reasoning.

-

The main problem in a theodicy arises from the fact that the tension between whether or not God wills suffering presupposes a rational division between God's omnipotence (power) and pathos (love). Such a positivist and rational division does not reckon with the fact that love and "omnipotence" are not two different entities or attributes, but that both are manifestations of God's faithfulness towards humankind. They are not opposed; they are an expression of God's active involvement in our human history and His sincere identification with our human predicaments.

-

God's revelation is multifaceted and takes on different shapes according to contextual and cultural issues. It is difficult to derive one final solution regarding the will of God from Scripture. It is, therefore, unnecessary to choose between the inclusive formula, namely God wills suffering, or the exclusive formula, namely God does not will suffering. It depends on how one understands the intention of God's will within the framework of a theology of compassion.

-

Instead of traditional theodicy, a pastoral-theological assessment of suffering must be linked to hermeneutics, i.e. the endeavour to link a human being's understanding of God to painful life events in such a way that people are comforted by, and empowered to hope. Instead of a rational answer and an explanatory model, a hermeneutical approach bends the why question into a meaningful question: for what purpose?

-

The theology of pastoral care must take seriously the aspect of God's involvement11 with suffering, as well as His compassionate presence in a crisis. In light of a pastoral-theological interpretation of the issue of suffering, God's condescension becomes an important factor.

4. FROM THE IMPERIALISM OF THREAT POWER (THEISTIC THINKING) TO THE COMPASSION OF VULNERABLE POWER (THEOPASCHITIC THINKING)

Kearney (2011) draws heavily on Ricoeur's model of translation or "linguistic hospitality" and his quest to enact and to inhabit the Word/word of the Other/other. Spirituality should return to the dimension of the sacred in religious texts: the mystical or apothatic that appears in religious and wisdom thinking.

Out of the depths of the abyss a return and recovery of the sacred is possible, a re-birth - not of the God of omnipotence but a God of service and a sacramental "yes" to life. Maybe. God-may-be, again, anew. That is the eschatological wager of anatheism (Burkey 2010:162).

What does this "Returning of God after God" imply for a pastoral theology that takes seriously the human quest for meaning and hope?

Hall (1993:133) asserts that one of the most repressing God images of Christian theism and cultural Christian imperialism is "The Father Almighty" - an image that was misused in North America to insulate people from the reality of their situation. Such a theology, he argues, constitutes part of the repressive mechanisms of a class that can still camouflage the truth, economically and physically. Accordingly, such a theology is partly responsible for the oppression of others who suffer from first-world luxury, aggressiveness, and self-deceit (Hall 1993:133). Hall (1993:134) calls such a theology that maintains the image of deity, based on a power principle that can only comfort the comfortable, "a flagrantly disobedient theology". It also feeds fear. Fear of God's power becomes more predominant than closeness and adoration: "This paralyzing fear of God is one of the great human tragedies" (Nouwen 1994:121).

Nouwen's challenging remark poses the theological question for this article. If it is true that culture influences God images, how should God be interpreted and portrayed if Christian spirituality still influences our human quest for meaning? Which God image is then fitting for a new millennium if we want to return to God after God (the issue of anatheism)?

4.1 Renaming God within metaphorical theology and a pastoral hermeneutics

The challenge in a pastoral hermeneutics is to move towards a metaphorical understanding of God in order to attain clarity on what exactly is meant by the presence of God in suffering. Such a metaphorical understanding views traditional theodicies as simply honest human attempts to come to terms with the burning issue of meaning in suffering, not as an irrelevant philosophical abstraction, on the one hand, and wants to explain the meaning of metaphors regarding God's faithfulness within the context of our human misery, on the other.

4.2 God images and metaphors for God

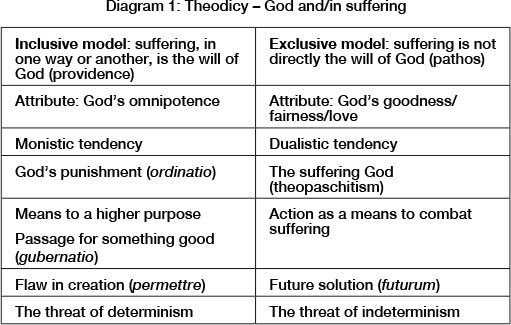

The following diagram is an attempt to merge the metaphorical and theodicy models. It indicates how an integrated model sheds more light on the complex interconnectedness of God images with our human experience of suffering, and the shaping of a believer's spiritual needs.The first block of the diagram illustrates how, for example, a monarchic metaphor, via the principle of authority and an understanding of God's mode of involvement (omnipotence), can influence the human experience of suffering and give rise to a better self-examination and self-understanding. For example, the family metaphor could have a most supportive effect on parishioners' experience of suffering; the covenantal metaphor could motivate parishioners to active self-responsibility, while the personal/love model has a liberating and consoling effect that could result in gratitude, joy and hope.

The diagram does not imply that the different metaphors and principles can be classified with the claim that the principle, mode, human experience and psycho-physical influence mentioned under each column can be isolated from the others. Metaphors have different meanings under different circumstances. They are even associated with each other, implying that principles and modes mentioned under one category are also relevant for, and applicable to other categories. Human experiences and psycho-physical influences and consequences are much more complex than portrayed in the diagram. In fact, they are all interrelated. The schematic diagram helps one understand the interplay between metaphor, principle, mode, experience, and personal consequences. If one applies this diagram to one's cultural context, it becomes clear that cultural and current philosophical issues determine, to a large extent, the appropriateness of a divine metaphor. In the Enlightenment's attack on patriarchy and monarchy (cf. Browning et al. 1997:8), it becomes evident that theology should reconsider the appropriateness of the monarchical and patriarchal paradigm. Indeed, God as King/Lord or Father has been put under severe pressure by what can be called "the philosophical deconstruction of patriarchy and monarchy", due to associations of violence, injustice, inequality, and exploitation. Instead of dominant rule and authoritarian power, the accent is currently on mutuality, reciprocity, and shared power. In seeking appropriate metaphors, pastoral care needs to take cognisance of this development.

One can assume that, in pastoral care, the metaphors coming from a family, covenant, or personal context should have a more consoling effect on believers than metaphors that reflect distance and control. However, sufferers are in need not only of solidarity, but also of authority. The latter reflects safety, security, steadfastness, and reliability. It depends on whether a monarchic paradigm is interpreted in terms of authoritarian paternalism or simply trustworthiness.

The issue of paternalism and authoritarianism leads one to the difficult issue of how to understand God's omnipotence. Is God a tyrant who, in His power, dictates every event in life? Is God the Almighty, the causal factor, behind all our suffering? Is the Why question an expression of doubt regarding God's power and control?

5. SUFFERING AND THE "OMNIPOTENCE OF GOD": TOWARDS A REINTERPRETATION OF "GOD'S POWER"

Inbody (1997) intends revising the concept of divine power as a metaphysical and theological concept, and to relate this to social relationships and suffering. The two key concepts of identification and transformation play a vital role in his theological revision. His argument in a nutshell:

God's power is God's identification with the suffering of the world, and includes God's vulnerability, God's powerlessness and God's compassion. God's power is the power of resurrection and transformation which brings new life out of the suffering and evil of the world (Inbody 1997:140).

Along the same line of the inclusive model and theopaschitic theology, Inbody emphasizes God's compassion in contrast to the apatheia of a theistic understanding of God. Omnipotence, as force and control, is no longer important, but rather omnipotence, as effect and persuasion, is significant. Power no longer means the capacity to impose one's will coercively onto a totally powerless object, but rather the power that affects another free centre of power through persuasion. The latter is possible, due to God's identification with suffering and the transformation of creation in terms of the resurrection. God's power is the power to create, to cure, and to rebuild, rather than the power to impose, that is, to control. Texts such as Jeremiah 4:14 and 13:27, as well as Hosea 6:4 and 11:8 describe God's pathos in His struggle for the future of His covenant people (cf. Fretheim 1984:100-139).

5.1 God's power (omnipotence): From pantokrator to compassionate being-with

In theology, God's omnipotence has often been interpreted, not in soteriological and sacrificial terms, but in Hellenistic terms: pantokrator. The latter is the Greek version of the Hebrew phrase 'el Saddaj (Hieronymus used the Latin version deus omnipotens). It is a fact that God revealed Himself several times as the Almighty. Genesis 17:1: "the Lord appeared to him [Abraham] and said 'I am God Almighty.'" (cf. Gen. 28:3, 35:11, 43:14, 49:25; Ex. 6:3). However, the etymology of 'el Saddaj is very complex and uncertain.12 Van der Zee (1983:79) concludes that omnipotence (imperialistic force) as such does not play an important role in Scripture. The concept "almighty God" is complex. In biblical terms, God's omnipotence is the unique way in which God is present among his people. "I would rather say: God's power is different (andersmachtig)" (Van der Zee 1983:80, own translation). Suurmond (1984:42) remarks that the Christian God must always be a strong God. Christians would very seldom view God as vulnerable and weak. However, vulnerability does not indicate that God is powerless; its indication that God's power is His love (love = omnipotence) is important. Omnipotence then becomes the overwhelming power of love and faithfulness that appeals to every human being's responsibility. According to Häring (1986:351-372), God is not a Pantokrator; neither should He be viewed in terms of Aristotle's potentia. God's power is His redeeming vulnerability and powerlessness; omnipotence is God's loving invitation to a relationship and covenant encounter that guarantees real freedom.According to Van de Beek (1984:91-92), behind the concept "omnipotence" lies the motive to perceive God as the absolute One, the Super King with a driving force (despotes). Behind every event God functions as the rational prima causa and immutable God (Blocher 1990; Sarot 1995:187). Instead of a rational explanatory model with its theistic and metaphysical schemata of interpretation as paradigmatic background, the article proposes the following theological paradigm shift: from the imperialism of threat power to the compassion of vulnerable power.

What is the implication of this paradigm shift for the intriguing Why question in pastoral caregiving?

6. LAMENT: THE THEOLOGICAL VARIANT PAINFUL VERSION OF THEODICY

The clearest expression of "Why?" in Scripture takes the form of a lament, in which the supplicant pours out all his/her anger and grief before God. Often, in the lament, God is severely accused. Such laments can be regarded as scriptural versions of the more philosophical and traditional approach to our human quest for meaning in suffering and our attempt to come to grips with the phenomenon of evil.

The lament is an example of the way in which the righteous people find it difficult to express to God their experience of the injustice of suffering (Westermann 1974). The lament thus makes it impossible to erase theodicy from the theological agenda as a purely speculative issue.13 The book of Job is a classic example of this form of lament.

The so-called lament psalms clearly reveal how Yahweh is accused.14In Psalm 44, the writer first gives a summary of Israel's trust and Yahweh's faithfulness in the past (vv. 1-8), but then, in verses 9-22, the writer proceeds to a dramatic petition in which Yahweh is told emphatically: "now you have rejected and humbled us" (v. 9). The lament surfaces in the harsh imperative, "Awake, O Lord! Why do you sleep? Rouse yourself! Do not reject us forever" (v. 23). Such a lament is not unusual in Israel's history. Another example is Psalm 10:1: "Why, O Lord, do you stand far off? Why do you hide yourself in times of trouble?"According to Brueggemann (1977:266), the lament has the following structure:

-

It does not flatter Yahweh, but confronts Him with bold trust.

-

It emerges from basic trust, rather than from brute anger. Accusing God - even in anger - implies an affirmation of faith in Him. The lament is never an indication of distrust in God's faithfulness, but rather an expression of profound trust.

-

In contrast to an anguished complaint of hopeless acceptance of a tragic lot, the lament expresses the expectation that God will act. Israel hopes for an interruption and an intervention that will answer the claims of the petition.15

One can distinguish between a complaint (the negative acceptance that leads to tragic resignation and stagnation; resigned acquiescence) and a lament (as protest and accusation that anticipates change and a new future). Complaining is self-perpetuating and counterproductive:Whenever I express my complaints in the hope of evoking pity and receiving the satisfaction I so much desire, the result is always the opposite of what I tried to get ... The tragedy is that, often, the complaint, once expressed, leads to that which is most feared: further rejection (Nouwen 1992:72-73).

7. CONCLUSION

What then does "Returning to God after God" imply?A reframing of God images within the realm of suffering and evil should move from the causative omni categories of threat power to the passion categories of vulnerable power (compassion), as articulated by, inter alia, a theopaschitic approach. God's power in suffering should portray Him in terms of overwhelming love and steadfast faithfulness. A theopaschitic approach does not start with a deterministic and apathetic principle of immutability, but rather with God's covenantal encounter and graceful identification with our human misery. The power of love should overcome the power of compulsion (Pinnock 1996:20).

In the Hebrew tradition, the scriptural narrative, as displayed in Exodus 3:14, founds the priority of compassion in the following relational categories: the act of "divine presencing which is a boundless and unending being-with" (Davies 2001:20).16 Compassion displayed an active and historical presence with, and for Israel, serving in the formation of a holy fellowship of people who would be mindful of the covenant and reverently honour His name and faithful promises.

God's hesed can be rendered as the source of Christian hope and the framework for our endeavour to address the human quest for meaning in a pastoral hermeneutics of care and counselling.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Achilles, E. 1975. Evil, bad, wickedness. In: C. Brown (ed.), The new international dictionary of New Testament theology, Volume 1 (Exeter: Paternoster), pp. 561-564. [ Links ]

Berger, P.L. 1992. A far glory: The quest for faith in an age of credulity. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

Berkhof, H. 1973. Christelijk geloof. Nijkerk: Callenbach. [ Links ]

Berkouwer, G.C. 1975. De voorzienigheid Gods. Kampen: Kok. [ Links ]

Blocher, H. 1990. Divine immutability. In: N.M. de S. Cameron (ed.), The Power and Weakness of God: Impassibility and Orthodoxy. Papers presented at the Third Edinburgh Conference in Christian Dogmatics, 1989. Edinburgh: Rutherford House Books, 1-22 [ Links ]

Burkey, J. 2010. A review of Richard Kearney's Anatheism: Returning to God after God. Journal of Cultural and Religious Theory 10(3):160-166. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 1977. The formfulness of grief. Interpretation 31:263-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002096437703100304 [ Links ]

Browning, D.S. et al. 1997. From culture wars to common ground: Religion and the American family debate. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Casdorff, Von s-A. 2016. Gefährdete Demokratie. Rational gegen radikal. Der Tagesspiegel 22661:1. [ Links ]

Cavanagh, M.E. 1992. The perception of God in pastoral counselling. Pastoral Psychology 41(9):75-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01032856 [ Links ]

Davies, O. 2001. A theology of compassion. Metaphysics of difference and the renewal of tradition. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

De Bernières, I. 2005. Birds without wings. London: Vintage. [ Links ]Docterman, E. 2015. Reclaiming conversation. Time. Special Report. Exodus. The Epic Migration to Europe and What Lies Ahead, 19 October:17. [ Links ]

Faulconbridge, G. & Young, S. 2015. World unites on Paris, Beirut. Cape Times, 16 November:1. [ Links ]

Feitsma, M. 1956. Het theopaschitisme: Een dogma-historische studie over de ontwikkeling van het theopaschitisch denken. Kampen: Kok. [ Links ]

Frankl, V. 1969. The doctor and the soul. London: Souvenir. [ Links ]

_______. 1975. Waarom lewe ek? Kaapstad: HAUM. [ Links ]

Fretheim, T.E. 1984. The suffering of God. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress. [ Links ]

Dawson, L.L. 2004. Religion and the quest for virtual community. In: Religion Online. Finding faith on the Internet (London: Routledge), pp. 75-88. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, G. & Schrage, W. 1977. Leiden. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [ Links ]

Hall, D.J. 1993. Professing the faith. Christian theology in a North American context. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Han, B-C. 2012. Transparenzgesellschaft. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz. [ Links ]

_______. 2013. Im Schwarm. Ansichten des Digitalen. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz. [ Links ]

Häring, H. 1986. Het kwaad als vraag naar Gods macht en machteloosheid. Tijdschrift voor Theologie 26(4):351-372. [ Links ]

Hedinger, U. 1972. Wider die Versöhnung Gottes mit dem Elendt. Eine Kritik des christlichen Theismus und A-theismus. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag. [ Links ]

Hick, J. 1966. Evil and the God of love. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Inbody, T. 1997. The transforming God: An interpretation of suffering and evil. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Jüngel, E. 1967. Gottes Sein ist im Werden. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck). [ Links ]

Kearney, R. 2011. Anatheism: Returning to God after God. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Ki-Moon, B. 2014. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon warns of 'turbulence' ahead, with wars, refugees, disease and climate change. [ Links ] [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.news.com.au/world/un-secretarygeneral-ban-kimoon-warns-of-turbulence-ahead-with-wars-refugees-disease-and-climate-change/story-fndir2ev-1227069828195 [2015, 20 October].

_______. 2015. Secretary-general Ban Ki-moon. [ Links ] [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.un.org/sg/headlines/ [2015, 21 October].

Kitamori, K. 1972. Theologie des Schmerzes Gottes. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck. [ Links ]

Leibniz, G.W. 1951. Theodicy: Essays on the goodness of God, the freedom of man, and the origin of evil. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Louw, D.J. 2015. Wholeness in hope care. On nurturing the beauty of the human soul in spiritual healing. In: D.J. Louw, U. Elsdörfer & S. van der Watt (eds), Pastoral care and spiritual healing, Volume 3 (Wien/Zürich: Lit Verlag), pp. 625. [ Links ]

Maddi, S.R. 2012. Creating meaning through making decisions. In: P.T.P. Wong (ed.), The human quest for meaning. Theories, research, and applications (London: Routledge), pp. 57-79. [ Links ]

Maritain, J. 1963. Dieu et la permission du mal: Textes et études philosophiques. Paris: De Brouwer. [ Links ]

Meeks, M.D. 1974. Origins of the theology of hope. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J. 1972. Der gekreuzigte Gott. München: Kaiser. [ Links ]

Nouwen, J.M. 1992. The return of the prodigal son: A story of homecoming. New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

_______. 1994. The wounded healer: Ministry in contemporary society. New York: Image. [ Links ]

Obama, B. 2014. [ Links ] [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/24/remarks-president-obama-address-united-nations-general-assembly [2015, 20 October].

O'Connor, D. 1998. God and inscrutable evil: In defence of theism and atheism. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Pinnock, C.H. 1996. God's sovereignty in today's world. Theology Today 53(1):15-21.Reuters [ Links ]

_______. 2015. Paris killings an attack on the civilised world, says Obama. Cape Argus, 16 November:11. [ Links ]

Sarot, M. 1995. Pastoral counselling and the compassionate God. Pastoral Psychology 43(3):185-190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02253786 [ Links ]

Sölle, D. 1973. Leiden. Stuttgart: Kreuz. [ Links ]

Sparn, W. 1980. Leiden. Erfahrung und Denken. München: Kaiser. Theologische Bücherei 67. [ Links ]

Suurmond, P.B. 19841. God is machtig - maar hoe? Baarn: Ten Have. [ Links ]

Taleb, N.N. 2010. The black swan. The impact ofthe highly improbable. London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Van Beek, A.M. 1982. Grief and theodicy: An attempt to determine the usefulness of a rational approach following personal loss. London: University Microfilms. [ Links ]

Van de Beek, A. 1984. Waarom? Over lijden, schuld en God. Nijkerk: Callenbach. [ Links ]

Van der Zee, W.R. 19832. Wie heeft daar woorden voor? ,s-Gravenhage: Boekencentrum. [ Links ]

Vick, K. 2015. The great migration. In: Time. Special Report. Exodus. The epic migration to Europe and what lies ahead, 19 October:26-34. [ Links ]

Weipert, M. 1976. addonaj (Gottesname). In: E. Jenni & C. Westermann (Hrsg.), Theologisches Handwörterbuch zum Alten Testament. Band II (München: Kaiser), sv. [ Links ]

Westermann, C. 1974. The role of the lament in the theology of the Old Testament. Interpretation 4:20-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002096437402800102 [ Links ]

Wiersinga, H. 1972. Verzoening als verandering. Baarn: Bosch & Keuning. [ Links ]

Wong, P.T.P. 2012. Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In: P.T.P. Wong (ed.), The human quest for meaning. Theories, research, and applications (London: Routledge), pp. 3-21. [ Links ]

1 Cf. Kearney 2011. Anatheism is about how to reintroduce the God issue and the notion of spirituality in postmodernity. Spirituality should return to the dimension of the sacred in religious texts: the mystical or apothatic that appears in religious and wisdom thinking.

2 An article by Walt (2015:8) refers to the gruesome events of 7 January in Paris. As a kind of revenge on a cartoon of the leader of the Islamic state of Iraq and Greater Syria, the attackers killed 12 people, among them three of France's best-known cartoonists, the paper's top editor and two police officers. It is argued that the massacre was an act foretold.

3 "Auf der politisch-gesellschaftlichen Ebene geht es zunemend lauter, aggresiver und radikaler zu - in der Tendenz demokratiegefährdend" (Casdorff 2016:1).

4 In the early 1960s, McLuhan wrote that the visual, individualistic print culture would soon be brought to an end by what he called "electronic interdependence": when electronic media replace visual culture with aural/oral culture. In this new age, humankind will move from individualism and fragmentation to a collective identity, with a "tribal base". McLuhan coined this new social organization the "global village".

5 Cavanagh (1992:80) asserts that "... a significant percentage of problems that people bring to ministers is caused, or at least is contributed to, by their unhelpful perceptions of God".

6 "Ihr fehlt die Richtung, nämlich der Sinn" (Han 2013:17).

7 Theos = God, dike = justice. Can one justify God, the ways of God, in light of the potential inexplicable existence of evil?

8 On the inscrutability of evil, cf. O'Connor (1998), who opts for a philosophical détente between scepticism (God's silence and the impossibility to discern any God-justifying reasons) and theism (the relation between God and possible reasons for inscrutable evil).

9 In his work on theodicy, Leibniz (1951:378) explains "that an imperfection in the part may be required for a greater perfection in the whole".

10 Cf. Maritain (1963:12) for the aspect of permission: "En d'autres termes le temps des theodicées à la Leibniz ou des justifications de Dieu qui ont l'air de plaider les circonstances atténuantes est decidement passé." Leibniz's (1951:383) own standpoint follows: "Likewise we may say that the consequent, or final and total divine will tends towards the production of as many goods as can be put together, whose combination thereby becomes determined, and involves also the permission of some evils and the exclusion of some goods, as the best possible plan the universe demands."

11 Sparn (1980:267): „Die theologische Arbeit am Theodizeeproblem wendet sich daher vor allem der Sprache des Leidens bzw. der Aufgabe zu, eine solche Sprache in nicht blos rational-kognitiver sondern auch in emotionaler Kommunikation zu lernen." Meeks (1974:57) asserts that Moltmann's theology accommodates the theodicy issue. He does this, not by giving an answer to theodicy, but by dealing with theodicy in terms of God's identification with suffering and the transformation of injustice: "The only solution to the problem of evil raised by Auschwitz and Hiroshima would be the eradication of such an evil. A satisfying answer to evil in the world is not to be found in explication of what it is good for, but only in a new world without evil."

12 Weipert (1976:875): „Ein Konsens ist bisher nicht zustandegekommen."

13 Sparn (1980:11): "So kann das christliche Misstrauen gegenüber jedes Art von Theodizee sich nicht mit der Auskunft begnügen, es handelt sich dabei gar nicht um ein theologisches, sondern um ein eingedrungenes spekulatives Problem."

14 According to Gerstenberger & Schrage (1977), one needs to distinguish between a lament and a complaint. While the complaint bemoans an irreparable tragedy, the lament is a form of objection or petition: an attempt to appeal for God's help in the midst of trouble.

15 In this regard, Brueggemann (1977:266, note 17) quotes Gerstenberger: „Alle Klage Israels kommt auf einen Durchbruch, selbst dann noch, wenn sie auf den Tod eingestellt ist oder gar zur Selbstverfluchung entarted. Sie setzt gegen allen Augenschein auf die Hilfe Jahwes. Eine Antwort auf die Klage wie sie im Gottesdienst ergehen könnte bedeutete Erfülling der Bitte."

16 "As the signifier of a divine quality, which can apply also to human relationships, the root rhm has much in common with the noun hesed, which denotes the fundamental orientation of God towards his people that grounds his compassion action. As 'loving-kindness' which is "active, social and enduring", hesed is Israel's assurance of God's unfailing benevolence" (Davies 2001:243).