Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Theologica

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.35 no.2 Bloemfontein 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v35i2.3

The strange case of the patriarchs in Jeremiah 33:261

C. Lombaard

Dept. Christian Spirituality, University of South Africa. E-mail: christolombaard@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Jeremiah 33:26 presents a number of interpretational questions, including the relationship of the Jeremiah 33:23-26 pericope with its textual surroundings; the compositional integrity of this pericope; the possible intentions of this passage, and the curious reference to the patriarchs - also with the name of Isaac spelt unusually. The unexpected reference to the patriarchs, in this instance, is of particular concern, since it has direct bearing on a new understanding of the patriarchs in history and text that the author has been developing. Why would the Old Testament patriarchs, so rarely referred to outside the Pentateuch, surface in this particular prophetic text? This article explores these issues, also as they relate to the author's theory-in-development on the patriarchs of Israel.

Keywords: Patriarchs, Jeremiah 33:26, Pentateuch and Prophets

Sleutelwoorde: Aartsvaders, Jeremia 33:26, Pentateug en Profete

1. AND THEN THERE WERE NONE

At times, the enigmas attached to a text have to be unravelled as in an Agatha Christie murder mystery. In one of her novels, And then there were none, there is indeed a character named Isaac (albeit surnamed Morris), deceased, whose interests are served by a man from Africa, surnamed Lombard (albeit spelt with one 'a'). The potential for analogies of that novel to this study does not go much further (since the fictitious Lombard character is also killed in the plot), except that in the Christie story, as in this Jeremiah text, the ones most closely under investigation provide the answers. Insights come through disclosure by the text, in this instance.

In the case under investigation, Jeremiah 33:23-26, the interrogation I provide is rather narrowly demarcated, focusing namely on the occurrence, in this instance, of the patriarchs and, then, the unexpected relationships within which they are found. The reason for this particular focus is that it springs from my still-developing programme of suggesting an alternate understanding of the patriarchs (summarised below). My interest is namely on something that is not entirely in vogue in present research, in either Jeremiah scholarship or Pentateuch theory, with their current leading emphases on the compositional history of these texts.2The exploration, in this instance, is still historical, with as main concern the relationship between text and the history - that of the narrated and that of the narrators, in their interrelated complexity - that gave birth thereto. The basic axiom is: references appear in a text for a reason.

Tentative as any such reasons proposed may be, as indeed they are in this instance, that is still more concrete, and a cautious advance in understanding, than the alternative of not paying attention (for various possible reasons) to such matters. This has indeed been the case in this instance, with relatively little attention paid to the patriarchal references in this text (exceptions include, for example, Erzberger 2013:672, 678; Lust 2004:66). Apart from being theoretically founded in order to qualify as such (Le Roux 2001:444-457), scholarship is also always explorative. This necessarily implies fallibility (or, in Popper's philosophy of science terms, falsifiability - cf. Popper 1963). The alternative to this for scholarship, though, would be: And then there is none.

2. FRAMED

The point of departure for the conceptual frame is to examine the patriarchs from a different angle. The initial critical strides in Old Testament scholarship on the patriarchs were naturally in relation to the Pentateuch texts. These included, as the main point, Alt's 1929 Gott der Väter hypothesis, in which the linked familial and religious ties between Abraham, Isaac and Jacob were severed, leaving scholarship ever since with a different understanding of these three patriarchs, and with a further altered vision on the relationship between the texts of the Old Testament and what they refer to (or better: how they refer to their subject matter). These are still the mainstays of critical understanding of the patriarchal figures. However, some issues remained, such as that identified already in 1835 by von Bolen (cf. Ska 2011), but seldom stated: if the patriarchs had been such a basic important part of the religion of ancient Israel-Judah, why then a centuries-long silence about them in extra-Pentateuchal texts? This would, as an unthinkable modern parallel, be akin to "founding" figures of a kind from

South African history such as Jan van Riebeeck (leader of the Dutch Cape settlement in 1652), Paul Kruger (late-19th century Transvaal president) and Nelson Mandela not finding reflection in anything but the most official documentation of this country for anything from 250 to 1000 years, depending on the dating accorded the patriarchs and the texts on them.

Orality stretches credulity as solution to such a conundrum (cf. Lombaard 2011:473). Yet, few alternatives remain, with archaeology as the first "second opinion" often turned to in Old Testament scholarship proving to be of no help with dating the patriarchs or their texts.

Therefore, investigating the patriarchs from the point of view of their extra-Pentateuchal references, which are relatively meagre, makes at least some sense, namely as a form of triangulation:3 to examine the same objects of inquiry from a different vantage point. Although the expectations of such an approach would be low, given the sparse body count of the patriarchs outside the texts of the Pentateuch, the results have been stimulating theoretically.

The main direct references to the patriarchs outside of the Pentateuch namely all occur in the prophets. Keeping for a moment to the usual dating assigned to these texts, these references may be indicated as follows:

- Jacob takes the earliest such bow, to be found in Hosea 12:1-15, dated slightly earlier than the 722 catastrophe in the North;

- Isaac arrives second on this scene, in the complex text of Amos 7:9-17 (Lombaard 2005:152-159), originating from the hands of Amos tradents and inserted into the received Amos traditions between 722 and 586, as a manner of recontextualising the received prophetic message;

- Abraham is the last to make a show on this stage, only in Deutero-Isaiah, namely in Isaiah 41:6-10 and 51:1-3,4 with as most probable date half a century after 586.

Though not unalterable, as will be shown in a moment, these provide at least generally stable dating points when considered in an overarching manner.5 "Not unalterable", though, as I have found convincing the cases built by Nissinen (1991) and Römer (2011) on Hosea 12 and by Bos (2013) on the remainder of the Hosea book, that as a whole this prophetic book is an early post-exilic document. This leaves the patriarchal order of origination, in these prophetic texts, as:

- Isaac, between the fall of the North and of the South;

- Jacob, shortly after the fall of the South;

- Abraham, simply a few decades later.

In addition, this alters the geographical focus, with no more than echoing northern influences on the patriarchal references in these prophetic texts, even though two of the prophetic figures concerned certainly worked in the North. Moreover, the patriarchal traditions are in all likelihood to be found among the people of the land, rather than among the socio-political elite of Jerusalem, the latter including the exiles from Jerusalem to Babylonia and the returnees half a century later.

The implications of this may be fleshed out quite substantially. This will, however, take away the focus from two matters that are relevant to the present argument:

- That taken from the perspective of these three texts, the patriarchal traditions as a group all appear in Judea within a century and a half to two centuries of one another, and subsequently become such a strong part of the developing post-exilic religion that, by the time of canonisation (as a process, not an event), this faith becomes unthinkable without, now, textually chronicled and historically imagined: first6, Abraham; then, Isaac; and then Jacob; and

- That the relationship between the patriarchal figures and the textual references to them must be reconsidered. Both the optimistic idea of a long oral tradition (a quarter or a half or, in extreme cases, even more than a full millennium of oral accounts about the individual patriarchal figures) and the more recent skeptical idea that all the patriarchal accounts are late literary creations are too extreme (cf. Lombaard 2013:276-288). More realistic, and in relation to the respective patriarchal references in these prophetic texts, certainly not implausible, would be that patriarchal figure and patriarchal reference do not transpire very far apart in time. Irrespective of whether these figures are regarded as having had some historical basis in tribal genealogy or had been fully mythological in origin, they were in any case composite iconic figureheads around whom group identities, which did not probe the historical/mythological-question, were then construed. The identity tales attached to these emergent icons found writing no more than a few decades from their zero point, with the process of renegotiated interrelationships continuing in writing as much as in developing history.

This juggling of the patriarchal order to the Abraham-Isaac-Jacob pattern may, therefore, well be understood as reflecting social adjustments in the power relations between the carriers of the traditions of these three patriarchs - a process which is typical with genealogies (cf. Wilson 1994:200-223). The "first-born", Isaac, is reduced, first, as evidenced - long accepted within Pentateuch studies - by his traditions being appropriated, namely Gen. 26 by Gen. 12 and 20, and second in my understanding of the Akedah (Lombaard 2008:907-919) to a middle child. Abraham became dominant in all respects, but the general group name and the construed tribal sub-identities of the people, which distinctions Jacob retained.

With other aspects of this understanding-in-development of the patriarchs from specifically the extra-Pentateuchal texts (cf. Lombaard 2013:907-919; Lombaard 2011:470-486; Lombaard 2010:1-5) not fully relevant in this instance, it remains for the moment to be pointed out that it was not merely among the patriarchal groups themselves that there seems to have been internal contention on social positioning (which then found reflection in the Pentateuchal texts). The conception on the patriarchs as a founding - now - family was within the developing Jewish religion itself one among a few conceptions that existed in post-exilic Judea, side by side, and not always unproblematically so. The very fact of the full diversity of theological strands taken up in the Hebrew Bible canonisation process, in full swing during the last half a millennium BCE, namely reflects (at least substantial parts of) the crowded theological idea world of that period. Whereas some of these idea strands found quite natural harmony with one another, such as Deuteronomistic theology and Mosaic legalism, others were ill at ease with one another: Ezra-Nehemiah's national-theological exclusivism versus Jonah's and Ruth's inclusivism, for instance. Somewhere in a kind of middle ground between these two possibilities of coalescing theologies and contrasting theologies, namely without much in common, but not really in competition with one another either, would lie three theological strands important for the Jeremiah 33:23-26 text: patriarchs, creation and kingship (so too Allen 2008:378-379).

3. THE CASE UNDER INVESTIGATION

The placement of Jeremiah 33:23-26 within its broader and narrower textual contexts present hardly any problem; there is much agreement on these structural matters as they relate to this text (even though the Jeremiah text itself is, in many respects, "untidy" - a characterisation of McKane (1986:xlix), cf. Osuji (2010:43-45) of the text of the entire Jeremiah book; cf. Holladay (1989:228)).7 The placement of Jeremiah 33:23-26 within its historical context has been undertaken with less certainty by exegetes, but is nevertheless not on infirm grounds. The placement of the text within its theological context has hardly ever been undertaken - Karrer-Grube (2009:120) does so only co-textually, not contextually.

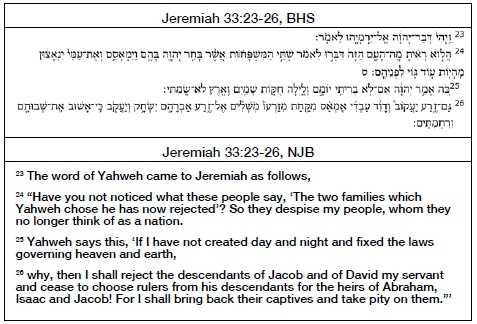

3.1 Jeremiah 33:23-26 in co-text

Within the broader construction possibilities of the 52 chapters of the Jeremiah book, with broadly speaking the first 25 chapters containing the Jeremiah prophecies, upon which follow his experiences (Clements 1988:7), chapters 30-33 form a clearly discrete collection.8 These four chapters themselves are built up by a series of compositions, probably successively, with chapters 30-31 as the Book of Comfort being appended by, first, chapter 32; then chapter 33; with the last part of chapter 33, namely 33:14-26, as a closing section evidently to be distinguished from 33:1-13 (cf., for example, Lundblom 1997:51-52; Allen 2008:376; Thompson 1980:597-598; Lust 2004:54-55). This last section, 33:14-26, of exclusively "Heilsankündigungen" (Holladay 1989:230) consists of a series of four sayings, related to one another in different ways, and with verses 23-26 undoubtedly a separate "promissory" text, as, for example, Brueggemann (2007:120-121; Brueggeman 1998:312) terms it (cf. Carrol 2006b:634; Stipp 1994:92-99, 133 & 136; Holladay 1989:230). On this general composition there is, widely, consensus.

There are multiple referential relations incorporated within this text - internally, to the remainder of the chapter, to the remainder of the Book of Comfort, across the Jeremiah corpus, and to much of the remainder of the Hebrew Bible literature (cf., for example, Schmid 1996; Erzberger 2013:666-682; Karrer-Grube 2009:105-107; Lust 1994:32, 38-45; Stipp 1994:93). To analyse all of them would not be productive in this instance; those that are pertinent to the case being built here, are indicated in 3.3 below.

Important, which is why all writers on this passage remark on it, is that this 33:14-26 section from Jeremiah does not appear in the Septuagint version, and is the largest section from Jeremiah not to find such reflection. This clearly has implications for the dating of 33:14-26: unless an alternate Hebrew Vorlage is posited, this pericope would have been composed after the LXX came into existence and, as many authors point out, would then be specifically created for the Masoretic text of Jeremiah9 with a view to the community it intended to address.

3.2 Jeremiah 33:23-26, dated

The prophet Jeremiah's work may be dated from 627 BCE and later, thus half a decade before the Josianic reforms (2 Kings 22) begin to take effect (cf., for example, Clements 1988:4). Though Jeremiah's prophecies may

be dated to such times, the texts on them come into being much later, with an involved developmental history. The 33:14-26 text constitutes one such "late addition to the book" (Clements 1988:199; Allen 2008:376); as to Jeremiah 33:23-26 specifically, Holladay (1989:229) (cf. Thompson 1980:604) affords it "a setting in the post-exilic period", probably towards the end of the 5th century BCE (Holladay 1989:229-230), and clearly from a hand that seeks different things than the remainder of the Jeremiah texts: it is "a post-Deuteronomistic postscript to the cycle of salvation expectations in 30-31" (Carrol 2006b:634). Karrer-Grube (2009:106-107) mentions the case for a later dating, which seems possible, though perhaps not extending into the 3rd century.

3.3 Jeremiah 33:23-26 within its theological frame

The most-discussed referential puzzle in these four verses is on what the שׁתּיְ המּשַׁפִּחְוָֹ֗ in verse 24 would refer to; a strong majority concludes that these refer to the Northern and Southern kingdoms, understood in this instance as the two major groups of Jacob descendants ("families"/"tribes") that together constituted the people of Israel-Judah (cf., for example, Lust 2004:62-66). This kind of language to refer to the two kingdoms is unique (Holladay 1989:230), and it probably demonstrates a (re)conciliatory attempt in imagining together quite separate past identities. A minority view (strongly supported by, for example, Karrer-Grube 2009:118-119) is that the two entities referred to, in this instance, are the kinship line and the patriarchal line, brought together into some form of concord. Whichever of these two interpretative options are chosen (I favour the former), this rhetorical move of rapprochement is instructive for the remainder of the argument to follow.

Clements (1988:199-201) identifies two main focal areas in the second half of Jeremiah 33 as the Davidic house and the priesthood of the Levitical line. Kingship and priesthood, in general, do not receive good press in the Jeremiah text (Jer. 7:1-15, 22:1-23:2; cf. ParkTaylor 2000:59-60; Brueggemann 1998:318-319); still, in chapter 33:14-26, there is a rehabilitation of these offices (Stipp 1994:135; Allen 2008:376). Such rapprochement can also be detected in the language related to the kingship in the immediately preceding text: the throne of David from Jeremiah 29:16 becomes in Jeremiah 33:17 the throne of the house of Israel, with the king who is referred to thrice in this half chapter from verse 14 onwards as עבַדְּיִ (Stipp 1994:134, 135; Carrol 2006b:636, 638; cf. Karrer-Grube 2009:116-117). A trend of some kind of democratisation is thus to be discerned in this instance (so too Lust 2004:63): officialdom is brought closer to the people.

In an unusual way, the patriarchs are brought into this play of toenadering, too. Whereas there is ample talk of "the fathers" in the book of Jeremiah, in both positive and negative senses, the reference to the actual three patriarchs of Israel is found only in Jeremiah 33:26 (Römer 1990:402).10Moreover, the three patriarchs are placed in a direct relationship with the Davidic line, with the latter accorded a servant-leadership position, and the divine pronouncement on this (Jer. 33:25) drawing directly on images from creation theology.

In addition, if the verse immediately preceding our pericope is read, a similar scene is found: patriarchs, kingship and priesthood are brought in close relation to one another by means of a divine pronouncement:

Jer. 33:22: As surely as the array of heaven cannot be counted, nor the sand of the sea be measured, so surely shall I increase the heirs of David my servant and the Levites who minister to me.

As Thompson (1980:603; cf. Allen 2008:378; Brueggemann 2007:129) astutely observes on this:

The promise of an innumerable posterity once given to the patriarchs (Gen. 13:16; 15:5; 22:17;11 etc.) is now applied to the descendants of David as well as of the priests.

Having indicated this novelty, Thompson (1980:603) then continues on Jeremiah 33:23-24: "The horizon is widened again ... to include the whole nation".

4. AND THEN THEY WERE ONE

To summarise: Jeremiah 33:23-26 is a stranger in its own midsts. Not unrelated to its literary contexts, drawing on those in different ways, Jeremiah 33:23-26 is not fully at one with them either. It rather seeks a kind of oneness within its diverse socio-theological context. Jeremiah 33:2326 intends to set up something new, by bringing into relation previously less associated, in a way socially speaking, parallel-running theological streams: patriarchal kinship, Davidic kingship, creation theology, and going slightly wider, also with the inclusion of the Levite priests and the divine blessing of progeny as a promise of a positive future. Nor should be forgotten the "two families" uniquely brought together in this instance, despite the lack of full certainly on the denotation of this expression. A diversity of parties/interests are drawn together in these few verses. Without grandeur, with this alignment of interests, these verses seek to influence their social surroundings. No intended theological programme is worked out in any detail. Uniting theological streams is presented simply as divine pronouncement.

Any broader intent may possibly be gleaned from the co-texts hinted at within these verses: among other texts, these are perhaps just hintedat interrelations, to Nehemiah 8-9 in which a theological project of Israel under the Torah is programmatically (and historically very successfully) set up, and to the Genesis 22 insertion of verses 15-18, in which Abraham is set up as a model believer for all times. These co-textual relations are, however, for further investigation. For the moment, the given that the patriarchs are mentioned in this instance, in a late addition to the Jeremiah text, is theologically interesting: that the blessing of posterity associated with the patriarchs is, in this context, carried over to the kingship and priesthood too, seems to be more than simply metaphor. In vision here is a rapprochement in post-exilic Judea between different theological strands that are not at odds, yet not in clear cooperation either, traditionally. This seems an idealistic move, and one that had little effect in history: a theocratic society under the official influence of the priesthood, under the ideological influence of law, and under the implied divine threat of Deuteronomistic theology, carried the day from second temple Judaism onwards. So, perhaps what we see in these few verses from Jeremiah 33 is just an idealist moment seeking greater rapprochement between some theological strands. This had, however, proved socially unsuccessful in history. Or was such rapprochement most concretely given expression to in the canon?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, LC. 2008. Jeremiah. A commentary. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Bos, J.M. 2013. Reconsidering the date and provenance of the book of Hosea: The case for Persian-period Yehud. London: Bloomsbury T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 1998. A commentary on Jeremiah: Exile and homecoming. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W. 2007. The theology of the book of Jeremiah. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Old Testament Theology commentary series. [ Links ]

Carrol, R.P. 2006a [1986]. Jeremiah, Vol. 1. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. [ Links ]

Carrol, R.P. 2006b [1986]. Jeremiah, Vol. 2. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. [ Links ]

Clements, R.E. 1988. Jeremiah. A Bible commentary for teaching and preaching. Atlanta: John Knox Press. Interpretation commentary series. [ Links ]

Dozeman, T.B., Schmid, K. & Schwartz, B.J. (Eds.) 2011. The Pentateuch. International perspectives on current research. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. FAT 78. [ Links ]

Erzberger, J. 2013. Jeremiah 33:14-26: The question of text stability and the devaluation of kingship. Old Testament Essays 26(3):663-683. [ Links ]

Given, L. (Ed.) 2008. The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Hess, R.S. & Tsumura, D.T. (Eds.) 1994. "I studied inscriptions from before the flood". Ancient Near Eastern, literary, and linguistic approaches to Genesis 1-11. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Holladay, W.L. 1989. Jeremiah 2. A commentary on the book of Jeremiah chapters 26-52. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Karrer-Grube, C. 2009. Von der Rezeption zur Redaktion. Eine intertextuelle Analyse von Jeremia 33,14-26. In: C. Karrer-Grube, J. Krispenz, T. Krüger, C. Rose & A. Schellenberg (eds.), Sprachen - Bilder - Klänge. Dimensionen der Theologie im Alten Testament und in seine Umfeld (Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, Festschrift für Rüdiger Bartelmus zu seinem 65. Geburtstag), pp. 105-121. [ Links ]

Karrer-Grube, C., Krispenz, J., Krüger, T., Rose, C. & Schellenberg, A. (Eds.) 2009. Sprachen - Bilder - Klänge. Dimensionen der Theologie im Alten Testament und in seine Umfeld. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. Festschrift für Rüdiger Bartelmus zu seinem 65. Geburtstag. [ Links ]

Le Roux, J.H. 2001. No theory, no science (or: Abraham is only known through theory). Old Testament Essays 14(3):444-457. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2005. What is Isaac doing in Amos 7? In: E. Otto & J. le Roux (eds.), A critical study of the Pentateuch. An encounter between Europe and Africa (Munich: LIT Verlag, Altes Testament und Moderne 20), pp. 152-159. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2008. Isaac multiplex: Genesis 22 in a new historical representation. HTS Theological Studies 64(2):907-919. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2009. The question of the fathers (twba) as patriarchs in Deuteronomy. Old Testament Essays 22(2):346-355. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2010. The exile of the patriarchs among the prophets: A new beginning, or first beginnings? Verbum et Ecclesia 31(1):1-5; DOI: 10.4102/ve.v31i1.408. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2011. The patriarchs and their Pentateuchal references: Outlines of a new understanding. Journal for Semitics/Tydskrif vir Semitistiek 20(2):470-486. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2013. Three old men? The patriarchs in the prophets (or: what do patriarchs look like, and where do we find them?). Journal for Semitics/Tydskrif vir Semitistiek 22(2):276-288. [ Links ]

Lundblom, J.R. 1997. Jeremiah. A study in ancient Hebrew rhetoric. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Lust, J. 1994. The diverse text forms of Jeremiah and history writing with Jer. 33 as a test case. Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 20(1):31-48. [ Links ]

Lust, J. 2004. Messianism and the Greek Version of Jeremiah: Jer. 23,5-6 and 33,14-26. In: J. Lust & K. Hauspie (eds), Messianism and the Septuagint: Collected essays (Leuven: Leuven University Press, Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 178), pp. 41-67. [ Links ]

Lust, J. & Hauspie, K. (Eds) 2004. Messianism and the Septuagint: Collected essays. Leuven: Leuven University Press, Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 178. [ Links ]

May, H.G. 1941a. The God of my father: A study of patriarchal religion. Journal of Bible and Religion 9(3):155-158, 199-200. [ Links ]

May, H.G. 1941b. The patriarchial idea of God. Journal of Biblical Literature 60(2):113-128. [ Links ]

McKane, W. 1986. A critical and exegetical commentary on Jeremiah. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

Nissinen, M. 1991. Prophetie, Redaktion und Fortschreibung im Hoseabuch. Studien zum Werdegang eines Prophetenbuches im Lichte von Hos 4 und 11. Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker. [ Links ]

Osuji, A.C. 2010. Where is the truth? Narrative exegesis and the question of true and false prophecy in Jer. 26-29 (MT). Leuven: Uitgeverij Peeters. [ Links ]

Otto, E. & Le Roux, J. (Eds.) 2005. A critical study of the Pentateuch. An encounter between Europe and Africa. Munich: LIT Verlag, Altes Testament und Moderne 20. [ Links ]

Park-Taylor, G.H. 2000. The formation of the book of Jeremiah: Doublets and recurring phrases. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [ Links ]

Popper, K.R. 1963. Conjectures and refutations. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [ Links ]

Römer, Τ. 1990. Israels Väter. Untersuchungen zur Väterthematik im Deuteronomium und in der deuteronomistischen Tradition. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag. [ Links ]

Römer, Τ. 2011. Extra-Pentateuchal biblical evidence for the existence of a Pentateuch? The case of the "historical summaries", especially in the Psalms. In: T.B. Dozeman, K. Schmid & B.J. Schwartz (eds.), The Pentateuch. International perspectives on current research (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, FAT 78), pp. 471-488. [ Links ]

Rothbauer, P. 2008. Triangulation. In: L. Given (ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.), pp. 893-895; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909.n468. [ Links ]

Schmid, K. 1996. Buchgestalten des Jeremiabuches. Untersuchungen zur Redaktions- und Rezeptionsgeschichte von Jer. 30-33 im Kontext des Buches. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag. WMANT 72. [ Links ]

Ska, J-L 2011. Anything new under the sun of Genesis? Paper read at the Society of Biblical Literature's annual international conference, 3-7 July 2011, King's College London. [ Links ]

Stipp, H-J. 1994. Das masoretische und das alexandrinische Sondergut des Jeremiabuches. Textgeschichtlicher Rang, Eingenarten, Triebkräfte. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag. [ Links ]

Thompson, J.A. 1980. The book of Jeremiah. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Van Seters, J. 1972. Confessional reformulation in the exilic period. Vetus Testamentum 22(4):448-459. [ Links ]

Wilson, R.R. 1994. The Old Testament genealogies in recent research. In: R.S. Hess & D.T. Tsumura (eds.), "I studied inscriptions from before the flood". Ancient Near Eastern, literary, and linguistic approaches to Genesis 1-11 (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns), pp. 200-223. [ Links ]

Wilson, R.R. 2014. Exegesis, expansion and tradition making in the book of Jeremiah. Paper presented at "Jeremiah's Scriptures: Production, reception, interaction, and transformation" conference, 22-26 June 2014, Monte Veritè, Ascona, Switzerland. [ Links ]

1 Paper presented at the Pro Pent 2014 meeting, Bass Lake, Pretoria.

2 For recent summaries of these research histories, see Wilson (2014) and Dozeman, Schmid & Schwartz (2011), respectively.

3 This is not to be confused with the methodological technique of triangulation at times encountered in the Humanities (cf., for example, Rothbauer 2008:893- 895), in which different methods are employed to study one's subject matter (this, on the mistaken assumption that such triangulation would render more reliable results, when in fact each method can simply render its own results, thus yielding greater diversity, but not greater depth of understanding). In this instance, the term 'triangulation' is used more in a perspectival sense.

4 Allen (2008:376) isolates this verse - specifically Isaiah 51:2 - among others as linking to the Jeremiah 33:26 reference to the patriarchs by name.

5 Cf. Römer (2011:471-474) for a summary of the recent debate on the Pentateuch/ Hexateuch/Enneateuch.

6 To misappropriate and only half-quote Matthew 20:16: οΰτως έσονται οί έσχατοι πρώτοι.

7 A noteworthy instance is the word (imgemaqui) in Jeremiah 33:20 and 25, which only occurs also in Nehemiah 9:19, thus creating the suspicion of a shared link.

8 Cf. Osuji (2010:19-21) on the foundational work of Duhm and Mowinckel; Carrol (2006a:38-50) provides a research overview.

9 As Erzberger (2013:673) formulates: "Besides Jer 33:14-26 being well integrated into its MT context, the interdependency of Jer 31:35-37 (MT) and Jer 33:20-26 speaks against any erroneous omission of Jer 33:14-26 by the LXX and makes any deliberate omission improbable".

10 In general, the references in Old Testament texts to "fathers" were only in time understood as indicating Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (May 1941a:156; May 1941b:113-128; Van Seters 1972:452; most substantively, Römer 1990; cf. Lombaard 2009:346-355).

11 It is worth noting that this Genesis 22 reference (which Brueggemann 1998:320 and Karrer-Grube 2009:116 also make) is a part of the late insertion of verses 15-18 into that text. This link should also be further explored: could this come from the same hand/circle?