Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.35 suppl.22 Bloemfontein 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v21i1.9s

Reasons for the migration of church members from one congregation to another1

I.M. BredenkampI; W.J. SchoemanII

IResearch Fellow in the Department of Practical Theology, Faculty of Theology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. E-mail: bredenkampim@ufs.ac.za

IIDepartment of Practical Theology, Faculty of Theology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. E-mail: schoemanw@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article2 aims to determine the reasons why members of one congregation migrate to another, and to identify factors that play a role in this process. These are determined by the nature and functioning of congregations. This qualitative research involved members of three different congregations that had recently experienced a positive growth in membership numbers. The effects of secularisation and the Enlightenment, and their consequences at various levels, as well as the theories of McDonaldisation and Consumerism were taken into consideration to explain the migration of church members between congregations. The answer is not simple in the sense that two tendencies can be identified: 'push' factors that activate the tendency to move out of the previous congregation, and a drawing or 'pulling' tendency, representing those factors that attract people. It can be stated that the reasons for migration can, to a large extent, be traced to the nature and functioning of the congregation. In addition, clear tendencies can be identified in terms of 'push' and 'pull' factors.

Keywords: Congregations, Membership migration, McDonaldisation, Consumerism

Sleutelwoorde: Gemeentes, Lidmaat migrasie, "McDonaldisation", Verbruikersmentaliteit

1.INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this study is twofold, namely to determine the reasons why members of one congregation migrate to another, and to identify the 'push' and 'pull' factors that play a role in this process. These are determined by the nature and functioning of congregations. This qualitative research study involved the members of three different congregations that had recently experienced a positive growth in membership numbers. Questionnaires were distributed to 50 members. In-depth interviews were conducted with three members to ensure that critical details and information had not been omitted. Theoretically, a multiparadigmatic approach was followed, combining insights from Sociology and Practical Theology. The research results were fairly conclusive, in the sense that a number of definite reasons for migration were identified. These could be contextualised in terms of the broader literature and theoretical frameworks. As is evident from this research and from research published in Church Mirror,3 migration between congregations constitutes a wake-up call for many congregations in a dramatically changing and postmodern society.

2.WHY MIGRATE?

Recently, media coverage of congregational and church affairs has become a frequent occurrence; matters that are relevant to congregations have featured in media reports on a regular basis (cf. Oosthuizen 2014:7; Hanekom 2014:3; Pretorius 2014:4-5). This phenomenon is not unique to South African congregations. Changes in denominations in, for example, the United States of America (USA) are a historically familiar occurrence (Glock & Bellah 1976:267-294; Glock, Ringer & Babbie 1967:1-9). What is also notable is the fact that new religious movements are arising, not only from the Christian religion, but also from Hinduism and Islam, inter alia (Hunt 2013:155; Zubaida 2009:545).

It is common knowledge that churches and congregations have experienced a decline in numbers as a result of, inter alia, the demise of members, the declining birth rate, and emigration. The phenomenon of 'church-free' and thus churchless members is also familiar. Less well known are the reasons why members migrate from one congregation to another, or move from one church denomination to another. In the USA, demographic shifts, urbanisation, the growth in the transport and communication industries, as well as industrial developments, had a radical impact on churches between 1820 and 1860:

Where established religion did not effectively cope with these social and economic changes new religious beliefs and structures replaced outmoded Protestant theologies and unwielding institutions and created a new established religion that could deal more fully with a reordered society (Glock & Bellah 1976:302).

In a more recent context, De Roest (2008:34) portrays the Dutch church scenario, which, in some respects, displays marked similarities to the situation in South African congregations. In The Netherlands, the bond with the church has drastically diminished among members. Among the youth, in particular, the connection with the church is extremely tenuous; numerous members with a weak church affiliation are considering the option of terminating their membership. The remaining congregants are increasingly older persons. One of the reasons for the weakening ties between members and their churches, according to De Roest (2008:37), is secularisation within the church, with people clinging to church attendance and church rituals, without any real experience of personal faith.

Migliore (2004:249-250) identifies four core problems that influence modern people's relationship with the church:

- The individualism of Western human beings.

- The fact that religious convictions and practices are assuming not only an individualised form, but also a privatised one.

- The church's bureaucratic structure (for example, rules, regulations and formal communication).

- The tension between the church's expressed beliefs and the actual practice of the church.

Numerous authors such as Heitink (2008:153), Burger (1999:13) and Schoeman (2011:484) have highlighted the issue of the involvement (or lack thereof) of church members, and the consequences thereof for the church and congregations. De Roest (2008:39), however, brings a fundamentally important argument to bear by pointing out that the stability and durability of Christian convictions and motivations requires a collective social context - a corporate Christian framework. A satisfactorily functioning faith, according to sociologists, cannot be successful beyond the church. Religious experiences will not take root if a community of fellow believers does not support them.

Viewed in this way, the Christian life of faith - of spiritual growth and development - is carried, to a high degree, by the community of the faithful.

It is a well-known fact that many traditional churches have experienced a decline in membership numbers over the past 20 years and more. The question arises as to why some churches, on the other hand, are experiencing more growth, and even a dramatic growth in numbers, and why some congregation members have migrated from one congregation to another.

2.1 Migration patterns of members in the Dutch Reformed Church

A frequently asked question pertains to the extent of the tendency of members to migrate from a more traditional or mainstream denomination to a more charismatic one. In an attempt to answer this question, one must distinguish between two types of migration, namely denominational migration (the migration of congregation members from one denomination to another) and congregational migration (the migration of members from one congregation to another).

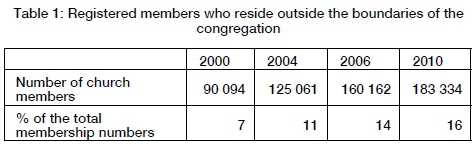

In the case of the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC), various surveys conducted by Church Mirror determined that denominational migration affected approximately 1.5% of the total membership numbers. In terms of the bigger picture of the DRC as a denomination, the gains and losses also approximately balance out (Schoeman 2011:484). The more extensive form of migration occurs between congregations. Church members are migrating, to an increasing degree and with increasing facility, between different congregations. Members decide which congregation they wish to join. This choice is being made increasingly less on the basis of the geographical address of the congregation or the member. It is no longer a matter of course that members will simply join the congregation within whose geographical boundaries they happen to reside. In 2010, over 180 000 church members, or 16% of the total membership numbers, lived beyond the congregational borders (Table 1). This tendency more than doubled within a ten-year period, and the actual figure is probably still higher, since the estimation only reflects the official figures. Up to a third of a congregation's members could reside outside its boundaries.

3. METHODOLOGY OF THE EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION

Interesting findings were made on the basis of an empirical investigation conducted during the first two months of 2014 among three Bloemfontein congregations4 that had undergone a fairly extensive to highly extensive growth in numbers. By means of questionnaires and interviews, the responses of 50 congregation members to questions, aimed at determining the reasons why members had migrated between congregations/churches, were analysed. The sample of 50 members from the three congregations consisted of 50% men and 50% women, all of whom were under the age of 59 and adult members of the congregation.5

The methodology is qualitative, and the interpretation of the data is inductive and deductive, with a critical-reflective approach to the drawing of conclusions. The procedure that was followed in the drawing of the sample consisted of a combination of theoretical sampling and purposeful sampling (cf. Henning 2011:71), since no register or publication exists that contains a list of the names of persons who have migrated between congregations. Both of these approaches target respondents who fulfil the criteria for the 'desirable participant'. These criteria are directed by the knowledge of the researcher. Non-probable sampling was used (Babbie & Mouton 2005:166). Since this research was primarily exploratory, as well as partly descriptive in nature, this method was adequate for the purposes of this investigation.

In the case of each congregation, the congregation leaders identified a few members, known to them, who had migrated. As such, persons who had migrated to the Doxa Deo in Fichardt Park, the Baptiste Kerk [Baptist Church] in Langenhoven Park, and the Apostoliese Geloofsending (AGS) [Apostolic Faith Mission (AFM)] in Universitas, were selected to complete questionnaires on a basis of confidentiality. This was followed by confidential interviews with individual members from all three congregations (only one interview was conducted per congregation, as a confirmation that core aspects had been addressed in the questionnaires, and with a view to arriving at a more complete picture of the congregational migration process).

Permission was obtained beforehand from the leadership of participating congregations. The questionnaire was made available to them, and the research process was explained. At no stage were respondents linked to a specific congregation. Thus, the aim was to identify respondents' reasons for migrating, and not to evaluate the congregations. The completed questionnaires were processed electronically. Thereafter, individual interviews were conducted with volunteers from each congregation -naturally, on the basis of anonymity.

The intention was to have a total of at least 60 questionnaires completed by (adult) congregation members who had come from another congregation and were willing to participate. Respondents were not to be related to one another. After this, a few interviews were conducted in order to obtain more details, as well as clarification of the reasons for migration. Naturally, the questions asked during the interviews were related to the questions in the questionnaire, with the focus on obtaining further clarification of the reasons for migration, as well as elaborations and explanations in respect thereof. The interview schedule entailed the following questions:

- Why is the church (congregation) important to you?

- What meaning/value does the church hold for your marriage, family and community?

- What were your most important reasons for leaving your previous congregation?

- What were your most important reasons for joining your current congregation?

- What is/are the norm(s)/criterion (criteria) for right and wrong in your congregation (dogma, doctrine, the pastor/minister, leaders, the Bible)?

- How do you give effect to your gifts and talents in the congregation?

- How do you deal with expansion/growth in your congregation?

- Does your congregation enable you to withstand the spirit of the times (secularisation, materialism, individualism, autonomy, self-sufficiency, postmodernism)?

- Does your congregation practise what it preaches?

- Is there anything you would like to add?

The research problem pertained to the reasons for the migration of members from one congregation to another (and not to migration within the same church affiliation). In addition, the aim was to distinguish the 'push' and 'pull' factors that played a role in the migration process. The point of departure of the investigation was the assumption that factors inherent to the nature and functioning of congregations themselves would furnish the reasons for the migration of congregation members.

4. A THEORETICAL REFLECTION ON CONGREGATIONAL MIGRATION

As indicated earlier, the church and congregations have faced numerous challenges recently. In Heitink's (2007:19-21) view, the stagnation within the church is one of the greatest crises in the history of the church; yet this does not comprise a cause for discouragement, but rather for re-orientation. Heitink (2007:22-23) goes on to identify eight factors that are fundamental to stagnation in the church. Since stagnation may be a reason for migration, and since these factors may comprise 'push' factors causing people to leave congregations, the factors identified by Heithink were regarded as important for this research.

- First, culture: Heitink points out that, in our time, people's lives and culture, and their everyday activities, take place outside of the church. People see themselves as self-sufficient, and no longer 'need' the church.

- The second factor is that of religious education. Every new generation has become less religious and less involved in the church.

- Heitink calls the third factor "identity". Something is amiss in the Christian tradition, in the sense that it apparently no longer inspires people.

- The fourth factor is related to the meaning attributed to membership of the church. The church is traditionally a compulsory or mandatory ("verplichtende") community that is carried by its members, while in modern times, membership is characterised, to a large degree, by a tendency to remain free of ties within the church ("vrijblijvendheid").

- Heitink refers to the fifth factor as a lack of recruiting capacity ("werfkracht"). Hardly any growth occurs from the outside, and the church does not do a great deal to win people for Christ.

- The sixth factor is that of ritual. The church is a ritualistic community, as is clear from all its feasts and celebrations. According to Heitink (2007:23), it is in this regard that the erosion is at its most acute. Fewer people attend the relevant church services; those who stay away feel that they have not missed a great deal. Heitink (2007:23) pointedly observes that, if the demand decreases, one should carefully examine what is being supplied.

- He identifies the seventh factor as a lack of leadership at all levels in the church. Nearly all organisations are concerned with organisational development; but the church is lacking in inspired leadership.

- The eighth factor is that of spirituality; in other words, the personal faith of members. Nowadays, there has been a shortage of spiritual experience and inspiration. Too many of the faithful are experiencing a "need for fresh air".

However, Heitink (2007:23) makes it clear that the foregoing observations are based on quantitative aspects that should not be confused with qualitative factors.

Although this scenario is mainly based on the situation in The Netherlands, it is probably also applicable, to a large extent, to numerous congregations - and the church as a whole - in South Africa. According to Heitink (2007:25), the church is that which is "of God". It is also defined by the metaphors that are used to refer to the church, and which all underscore a single principle. The church follows a basic theological pattern that can scarcely be reconciled with the concept of stagnation. The metaphors in question are: "God's people on their way (on a pilgrimage); the Body of Christ; the Temple of the Holy Spirit; the Bride of Christ" (Heitink 2007:26-28). In Heitink's view, the characteristics of the church are "Holiness, Unity, Catholicity and Apostolicity" (Heitink 2007:28-31). He quotes Berkkof, who imputes a threefold character to the church, namely the church as an institution; the church as a community, and the church as a series of "bridging events", referring to the ongoing movement between God and the world (Heitink 2007:37).

Regarding the church as an institution, Heitink discerns four objectives. He calls the first "inculturation"; i.e., integration into a foreign culture as an operationalisation of the cultural factor. The church is a cultural factor of significance. Over the centuries, the church has affiliated itself with diverse cultures and, in the process, safeguarded its own existence (Heitink 2007:38). The second objective, "integration", comprises the operationalisation of the identity factor. There are a large variety of faith communities within the church - a factor that creates room for tension and even conflict. Heitink (2007:38) raises the question: How can the church regain its identity in the midst of so much diversity? The third objective, "evangelisation", entails the operationalisation of the factor of recruiting capacity. Wherever the church finds an affinity with people and groups in its vicinity, it exercises an influence towards the outside by means of its utterances and actions, and thereby experiences growth, in both a qualitative and a quantitative respect (cf. Heitink 2007:38). The fourth objective, "organisation", entails the operationalisation of the leadership factor. For Heitink, the question is that of whether the manner in which the church is organised is not, in fact, co-responsible for the increasing stagnation. Organisational development should, therefore, also comprise one of the objectives of an institution (Heitink 2007:39).

With respect of the church as a community, Heitink distinguishes four functions in the formation of a faith community. The first is that of "initiation". This entails the operationalisation of the factor of religious education and guidance; the incorporation into the life of the congregation. The second function, "participation", is concerned with the operationalisation of the factor of membership; the personal participation in the life of the church. It brings specific obligations along with it; this is how involvement in the church comes into being (Heitink 2007:39). The third function, "congregation", refers to the congregational assembly as the basis of church actions. What is at issue, in this instance, is the operationalisation of the factor of ritual. The church's gatherings, Sunday services and the ritual celebration of specific occasions make the church visible. These gatherings are held for the praise and glory of God, and the salvation and welfare of human beings (Heitink 2007:40). The fourth function, "contemplation", entails the operationalisation of the factor of spirituality, and pertains to the church as the community of believers, the nourishment of individual faith within the congregation. According to Heitink (2007:40), faith is a gift of God, and not an act of man. In addition, however, faith requires experience, understanding, and worship. He adds that therein lies the deepest mystery of the church.

A retrospective glance at the role of culture in congregational life is necessary at this point. Following Heitink (2007:44), culture can be defined and summed up as the lifestyle of a community. During the 1960s and 1970s, a cultural schism took place in The Netherlands, as a result of which society underwent a dramatic change. According to Heitink, the church was strongly associated with perceptions, values and norms from a bygone age, and was unable to find resonance or fit in with a rapidly changing culture. In other words, the essential learning process involved in intrinsically associating itself with a new culture on the basis of the Christian tradition, thereby establishing a sense of unity and solidarity, was stagnating (Heitink 2007:44).6

Other interpretations were increasingly rejected, because they did not correspond with the values and norms of the church. Heitink (2007:44) called the mentioned process "inculturation". In his view, the church and faith assume a different form in a different cultural situation or scenario.

In this way, tension arises between the continuity of the tradition and an ever-growing discontinuity in respect of the cultural reality. Through the centuries, Christianity has succeeded in associating itself with changed cultures, but ever since the 1960s, the church has no longer been able to do so. The consequences included an exodus of people from the church and a loss of tradition. The stagnation that set in can mostly be linked to the secularisation process. Heitink (2007:45) raises the question as to why, at this specific time juncture, the church was unable to succeed in building a bridge towards a new epoch. The reason, he asserts, is that - ever since New Testament times - the church has had a tradition of Christianisation of many centuries' standing. A few examples in this regard include the Hellenistic, Graeco-Roman, Celtic and Germanic cultures during the Middle Ages, as well as the Reformation (Heitink 2007:45-49).

This schism entailed, inter alia, the questioning of the culture of authority. The authority of parents, teachers, politicians as well as of spiritual and church leaders was called into question. The traditional morals in the pedagogical and sexual domains were questioned. Democracy, in other words, joint decision-making, co-partnership and a shared right of speech, took over. In the church, too, traditional theology was questioned. The authority of the Scriptures, the offices, and the precepts of the church were also called into question. Liberation theology and feminist theology were on the rise. Numerous aspects of church doctrine were questioned; the creation, the fall and the hereafter, for example, became subjects of debate. The secularisation process spilled over into the entire cultural landscape, including the church. In this process, the Christianisation process, inter alia, was adversely affected (Heitink 2007:50-51).

The effects of secularisation and the Enlightenment (Aufklärung) had consequences, at the individual level, for faith and the church, and at the public level with regard to norms, values and actions (Heitink 2007:55-59). At the individual level, the person began to assume responsibility for his/her own life, his/her own future and own choices. Fundamental to this factor, according to Heitink, was a consciousness of freedom, independence, adulthood and responsibility. The word 'autonomy' literally means that the human being is his/her own lawgiver (Heitink 2007:59). The impact at the sociocultural level, which includes faith and the church, was similarly dramatic. The process of secularisation since the 1960s in The Netherlands comprises evidence of this. By 1900, 3% of the population were no longer attending church; a century later, that figure had risen to 40% (Heitink 2007:63), to mention but one example. The impact on the public domain can be summarised in a single sentence: "Society is becoming more brutal and aggressive" (Heitink 2007:70). Naturally, the impact on the above-mentioned domains entails much more than the aspects that have been pointed out in this instance. The intention behind this concise exposition is to focus attention on "inculturation", and on the challenge that lies therein for the church. Viewed as a whole, this challenge is also applicable to every congregation in South Africa. It is well known that individualism, secularisation, materialism and postmodernist tendencies are also dynamically at work in this country (cf. Burger 1999:9). The question once again arises: Do these factors influence migration between congregations? If so, how?

On the basis of the above eight factors that are fundamental to the stagnation of the church (Heitink 2007:22-23), as well as of Migliore's (2004:250) view regarding the problems that contemporary people have with the church - particularly the bureaucratic nature of the church as an institution, and the tension between the expressed belief of the church and its actual practice - the rationale was formulated for the assumption that the reasons for the migration of members lie in the nature and functioning of congregations themselves and that reasons for the 'push' and 'pull' factors can be discerned - in other words, reasons that operate in a causative manner (as triggers or catalysts) to induce people to leave a congregation, and reasons that operate as lures (magnets), attracting people towards a congregation.

The multidimensionalism, dynamics, interwovenness and complexity of this framework can hardly be over-emphasised. This factor is crucial to this investigation, since hardly an aspect, an event, or a phenomenon in the church as an institution (whether in a theoretical or a practical sense) can be identified that cannot be accommodated within this framework, including creation, the fall, conversion, liturgy, dogma, and confession. In this way, a broad frame of reference is created, against which the views of migrating members can be projected, and which can facilitate a critical-reflective interpretation.

From the foregoing theoretical discussion, it is clear that not only practical theology, but also several other disciplines shed light on congregations, congregational activities and religion in the broadest sense. Hill (1973:1-70) quotes the contributions of Weber, Troeltsch, Nebuhr, Becker, Pope and numerous others in this regard. The sociological perspectives of Ritzer (2007:263-266), as embodied in "McDonaldisation", and Baudrillard's (1998:passim) contribution on the Consumer Culture ("Consumerism") were among the theoretical building blocks of this investigation, since both have already been applied in the religious domain - in the case of McDonaldisation, by Erre (2009:21-42), and in that of Consumer Culture, by Conradie (2009:page no?). A concise elucidation of both perspectives will be provided below.

The McDonaldisation process has the following five fundamental dimensions: "Efficiency. Calculability. Predictability. Control. The irrationality of rationality" (Ritzer 2007:266-268).

The relevance of this perspective for the study lies in the fact that research has already highlighted the influence of McDonaldisation on the church. Drane (as quoted by Erre 2009:34) traces the characteristic efficiency (of McDonaldisation) in the western views regarding the church, in aspects such as, inter alia, the pre-packed spirituality that is currently commonplace. The following quotation articulates Drane's application of this principle to the church:

We have how-to manuals on every conceivable topic, all to be done in 30 minutes a day or less (in this way, much spiritual growth stuff sounds a lot like the infomercials we see for exercise products on T.V.). We have one minute Bibles and curricula that we can work through in only fifteen minutes a day. Worship services are carefully planned out, and we dread going one or two minutes over lest the service immediately after start late. We allow others to do the thinking for us and serve it up to us in nice tidy efficient bundles. The obvious problem with this is that the spiritual life doesn't work this way - it is often anything but efficient (Drane, as quoted in Erre 2009:34).

The prepackaged worship services and spiritual disciplines are not true to Scripture, and neither are they true to life. In Erre's (2009:34) view, this reflects the difference between instant meals (fast food) and home-prepared meals - one of these may be more efficient, but is not the best option for the member.

The principle of calculability lies in the contemporary human being's obsession with keeping score of things, and the quantification thereof. The underlying motive is the conviction that the more we have of something, the better. "Our American fascination with numbers, ranking, and size borders on idolatry and a sellout to the needs of our own ego" (Erre 2009:35). Moreover, Drane (as quoted in Erre 2009:35) points out that church growth, in most instances, means taking members over from other churches. The percentage of Christians, relative to the population of the USA, is in the process of decreasing.

To value calculability, Drane argues, is to focus on filling the building rather than filling the people. We should not be focused on asking how many people attend. Instead, the question should be: What kind of people are we becoming? (Erre 2009:35).

The third principle, predictability, requires discipline, order, procedures, systematisation, formulation, routine, consistency and methodical action; in this way, we know what to expect and how to avoid surprises (Erre 2009:35). Erre (2009:36) points out how clearly this phenomenon is manifesting itself in American church culture, by making things uniform and reproducible. The processes of faith and discipleship are homogenised, in terms of a series of steps that are supposed to work for everybody:

We ran to the next new fix, program, idea, sermon, series or whatever. Because of our impatience with prayer and incarnation, we settle for what is merely predictable, meaning that we can structure and plan and manage outcomes. Again, there is a place for this, but it is often a substitute for reliance on the Holy Spirit and willingness to wait in dependence on Him (Erre 2009:36).

Erre (2009:36) goes even further by pointing out the unpredictability of Jesus and the Holy Spirit. As far as control is concerned, this argument is interwoven with all the other principles. It would appear that churches want to make disciples of churches, rather than disciples of Jesus:

Very often our version of following Jesus gets held up as the only way to do it, and those who do differently are rarely welcomed. Power and control undergird a lot of the ways we as pastors lead our churches.

Just as the frame of reference of the tasks of Practical Theology, and thus of the church, highlights the relevance of the foregoing for the church, so the principles of McDonaldisation also highlight the relevance thereof for the church and, ultimately, also for this study, as succinctly pointed out earlier on the basis of Drane's and Erre's work.

A further theoretical building block from a sociological point of view is the Consumerist perspective of Baudrillard (cf. Ritzer 2007:passim; Baudrillard 1998:31, 49-69; Conradie 2009:21-33). Without further elaborating on this particular theoretical foundation, we would like to briefly refer to the relevance thereof. Conradie (2009:170-190) points out that the Consumerist culture impacts on religion in various ways. A few examples include:

- The commercialisation of religion.

- An increase in the number of variations of forms of public worship, liturgical styles, church music and rivalry among ministers and preachers.

- The often negative impact of the communication media.

- The often negative influence of the consumerist culture on the concept of the church, and on that of faith.

- A corporate style of church management.

- The impact of the consumer-friendly church ethos.

Both theories should be considered within the broad perspective of Globalism.

5. AN ANALYSIS OF THE EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

Against the background of the foregoing theoretical discussion, the respondents' responses can now be considered with regard to their previous and current congregations. The results are summarized below.

5.1 Biographical particulars of respondents

Eighty-six per cent (86%) Of the respondents, 86% are under the age of 53, with 50% male and 50 female. The overwhelming majority (77%) are employed on a full-time basis, or are self-employed. Of the respondents, 72% are married, and 24% are single.

5.2 The experience of respondents at previous congregations

5.2.1 The reasons for leaving the congregation

The most crucial reasons cited by respondents for changing their congregations include "problems with the sermons, minister, worship service and congregation" (cited in 35 of the 50 questionnaires); "a need for personal growth" (cited in 30 of the 50 questionnaires), and "a need to feel more at home" (cited in 25 of the 50 questionnaires). Of the 50 respondents, 37 had changed congregations only once during the previous ten years. A wide variety of other reasons were cited in much fewer cases. Of the respondents, 27 had previously been affiliated to the DRC; the remainder comprised much smaller numbers who had belonged to other churches. The investigation also highlighted the fact that those who had changed congregations had not been closely involved in their former congregations.

5.2.2 'Push' factors that induced respondents to leave their former congregations

Definite 'push' factors that influenced respondents to leave their former congregations, included "rigid, formal congregation meetings" (58%); "traditionalism" (54%); "unsatisfactory sermons" (46%), and "a lack of love" (22%). In response to the question as to how often respondents had experienced any of the following in a previous congregation - God's presence; inspiration; boredom; awe; joy; frustration; spontaneity, and the fulfilment of their calling - the feedback provided by respondents was as follows:

- God's presence was usually experienced by members in 48%; seldom, in 40%, and always, in only 8% of cases.

- Inspiration was experienced always, in 2%; usually, in 36%, and seldom, in 58% of cases.

- Boredom was always experienced by 4%; usually, by 50%, and seldom, by 42% of the respondents.

- Awe was always experienced by 2%; usually, by 28%, and seldom, by 66% of the respondents.

- Joy was experienced always, by 2%; usually, by 46%, and seldom, by 48% of the respondents.

- Frustration was experienced always, by 6%; usually, by 40%, and seldom, by 50% of the respondents.

- Spontaneity was experienced always, by 4%; usually, by 16%, and seldom, by 74% of the respondents.

- Fulfilment of their calling was experienced always, by 4%; usually, by 18%, and seldom, by 72% of the respondents.

What is significant is the fact that 46% of the respondents answered 'No' to the question as to whether their previous congregation had engaged in any programme or action aimed at reaching out to non-members (missionary actions, worship services for persons who spoke other languages, and so on), while 30% were either uncertain, or did not know. This may be indicative of a lack of involvement on the part of the respondent, as a result of which s/he did not know about such actions; but it could also signify that such actions either did not exist, or did not enjoy priority.

5.3 Respondents' experience in their current congregations

5.3.1 Respondents' considerations before and during their migration

It is significant that 94% of the respondents had first visited the 'new' congregation before joining it; 38% had first investigated the doctrine of the church; 62% had engaged in earnest prayer regarding the prospect of changing their congregation; 62% had held discussions with members of the congregation that they wished to join; 36% had discussed their intentions with the leader of the congregation that they wanted to join, and only 16% had also discussed the matter with the leader of their previous congregation.

It should be mentioned, at this point, that it was not determined what had happened to members who had not joined other congregations. Factors such as emigration, the death of members, as well as members who no longer belonged to any church, were thus not investigated. In fact, it is clear that those who had migrated to new congregations displayed a high degree of involvement in the spiritual activities of those congregations. It can thus be inferred that the congregation and congregational activities are important to them and, in many instances, highly important.

It is significant to note in this regard that 56% of the respondents indicated that the decision to migrate had been their own; 56% indicated that it had been predominantly their own decision, while 28% indicated that it had, to a large extent, been their own decision - thus, jointly, nearly 84% of the respondents had made their own decision in this regard. Their choices were, therefore, not influenced by the family, other relatives, leaders, or other members of the new congregation, but were made independently. Moreover, the following factors in the new congregation had made a strong impression on migrants: the role of music and singing (to a very great extent, in the case of 44%, and to a large extent, in the case of 26% - thus, considered jointly, applicable to 70% of the respondents); the role of the preaching of sermons (68% were very strongly affected, while 20% were strongly affected by this factor; thus, 88% considered jointly); hospitality, and the way in which the service was conducted.

Their experience of their new congregation must have been very positive for those who had migrated, given the high degree of involvement in, for example, small group activities (70%), as well as involvement in teaching, as a gift that they were able to bring to fruition in their new congregation (21 of the 50 respondents). In addition, the members of their new congregation were very compassionate. Thus, for example, 86% of the respondents indicated that, in times when they themselves had experienced need, they had received support. In addition, 100% of the respondents indicated that those in the congregation who were in need received support from members who reached out to them, although only 46% reached out, themselves, to those in need. Migrants are satisfied with their new congregation, to the extent that 98% of them would be prepared to invite a family member or friend to attend a church service. They provided a wide variety of reasons for their answers.

The size of the buildings, the modern and luxurious nature thereof, facilities such as parking and comfortable chairs and social activities such as bazaars and musical festivals did not motivate migrants to join a congregation. Hospitality (to a very great extent, 36%; to a large extent, 38%; thus, jointly, 74%), as well as music (to a very great extent, 26%; to a large extent, 28%; thus, jointly, 54%) were, in fact, considered. Preaching that was in line with Scripture was definitely an important consideration for those who migrated (90%).7 The administration of the Sacraments (66%), the authority of the Bible (98%), and the creed (54%) also featured among the factors deemed important. Missionary actions (78%) and evangelisation (78%) were likewise identified as important factors. Of the above, sermons that are in line with Scripture comprised the most important consideration for the majority of the respondents (43 out of 50); the authority of the Bible was the second most important consideration in terms of respondents' identification with their new congregation.

5.3.2 Prominent 'pull' factors that play a role in migration

The new congregation strongly motivated respondents to be dedicated to spiritual growth (90%); to support church activities aimed at spiritual growth (84%), and to attend church services (68%). In addition, 84% were of the opinion that the church services helped them a great deal in their everyday lives, while 88% opined that congregational activities helped them very much in terms of their everyday lives. A very strong argument for the changing of their congregation was the fact that respondents had experienced a need to move closer to God (96%). Some of the respondents (92%) read the Bible and engage in prayer and meditation on a daily basis; 50% hold daily or weekly home meetings, and 100% attend church services at least once a week, or more.

Of the respondents, 42% were of the opinion that the Bible is the Word of God, which should be interpreted literally word for word, while 20% were of the opinion that the Bible is the Word of God that should be understood in light of the historical context and church doctrine, and 36% were of the opinion that the Bible is the Word of God that should be understood in light of its historical and cultural context. Over 96% of the respondents agreed that their spiritual needs were satisfied in their new congregation. In addition, 80% of the respondents contribute financially to their new congregation.

During church services, the majority of the respondents experience God's presence (always, 50%; usually, 48%); inspiration (always, 47%; usually, 54%), and joy (always, 54%; usually, 42%). Respondents seldom experience frustration (84%) or boredom (90%). Of the respondents, 64% described the leadership style of the new congregation's spiritual leaders as "leadership that inspires people", and 82% of the respondents indicated that their congregation reaches out to non-members.

The most important factors cited by respondents as to why church members emigrate, are needs relating to ministry (30 out of 50 responses); not feeling at home in the congregation (20 out of 50 responses), and dissatisfaction with the congregation (22 out of 50 responses). In addition, the majority of the respondents were of the opinion that the most important task of the congregation is that of guiding members in following Christ (50%).

6. REASONS FOR MIGRATION: A FEW CONCLUSIONS8

The objective of the study was to identify those factors, inherent to congregational activities, that may furnish reasons for migration, including factors related to spiritual experience. The point of departure of this objective is the premise that the reasons for migration may reside in the nature and functioning of the congregations themselves.

6.1 Reasons for the migration of respondents

The respondents cited numerous decisive reasons as to why they had changed congregations. Arising from the 50 questionnaires, over 130 responses providing answers to this question were noted. However, the dominant reasons were: "The need for spiritual growth" (30 responses); "Problems with the church, minister, church services and congregation" (35 responses), and "The need to feel at home" (25 responses). This amounts to a joint total of 90 responses directly or indirectly pertaining to the nature and functioning of the previous congregation. These comprise reasons that are clearly regarded by the respondents as decisive ones. A wide variety of responses (40), however, also included factors that did not necessarily reflect the same sentiment, for example: "Need to be myself"; "Moved to a new residence"; "Got married", and "My husband was not happy in the previous congregation". In the answers to a control question, a high proportion of responses referred to the previous congregation as being "bound by traditionalism" (27 responses), or too "stiff and formal congregational gatherings" (29 responses), while the aspect of "unsatisfactory sermons" was mentioned 23 times. Thus, there was a fairly high correlation with similar reasons that had been cited in a previous question.

6.2 Experiences regarding church services and congregational involvement

Respondents' experience of church services was a factor associated with a high incidence of less positive experiences, for example: "seldom experience God's presence" (40%); "seldom experience inspiration" (58%); "usually experience boredom" (50%); "seldom experience awe" (66%); "seldom experience joy" (48%); "usually experience frustration" (40%); "seldom experience spontaneity" (74%), and "seldom experience fulfilment of calling" (72%). This correlates with the sense of not being at home and the problems with the minister, the church services and the congregation, as indicated in the answers to a previous question. However, the subjective nature of the listed experiences must be acknowledged.

A factor that further corroborates the assumption referred to above is the impact of the church services and the congregational activities of the previous congregation on the everyday lives of the respondents. On the basis hereof, it is clear that church services (46%) and congregational activities (38%) have a fairly low impact in this regard. Yet, although their impact was indicated as being fairly low, these aspects did, in fact, hold some value for respondents. What may be significant, in this instance, is the question regarding the lack of involvement. If the previous congregation furnished sufficient reasons for members to leave, why did such members tend to join another congregation? Why not simply leave the congregation and religion - "the church" - altogether, as occurs in some instances (cf. De Roest 2008:26-37; Migliore 2004:249-250; Burger 1999:1)?

On the basis of the argument thus far, it must be inferred that there are reasons inherent to the nature and functioning of the church that motivate people to migrate. In light of the contributions of De Roest, Heitink, Migliore and Burger, it must be assumed that, in many congregations, there are smaller or larger numbers of members who display hardly any, or a total lack of involvement. On the basis of the responses thus far, it is clear that, in spite of the reasons for dissatisfaction, for example not feeling "at home", or even problems experienced with "the sermons, minister and congregation", the migrants nevertheless acknowledged that both the church services and the congregational activities in the previous congregation had benefited them in their everyday lives, and that they had migrated with a view to "spiritual growth" and in order to "feel more at home". This clearly shows that the congregation and all the aspects associated therewith are still important to the migrants. Their reasons for migration indicate a longing for a congregation in which they can "feel at home". An observation of De Roest is worth mentioning in this regard. He refers to the decline in people's identification with, and involvement in a single institution. Involvement with traditional organisations, in particular, is diminishing. De Roest points out that, in modern western societies, the days of close ties between individuals and a single institution appear to be numbered - for example, the bonds between an individual and a church, or a party, or an industry, or an association. Mobility and selectiveness have broadened their horizons, and the days of lifelong institutional commitment seem to be over (De Roest 2008:26, 27). In addition, nowadays people can simply withdraw, while continuing to fulfil their needs in other ways, inter alia, via technology.

The scenario portrayed by De Roest with regard to the church's situation in The Netherlands displays strong similarities to the situation regarding some congregations in South Africa. He goes on to observe that one of the common complaints is that, whereas church members are in search of God and of Jesus Christ, and need to find inspiration for their everyday lives, all that they find in reality is meetings. In no single association, organisation or institution does one encounter so many meetings as in the church! From a religious perspective, one could say that many church members are - as it were - on standby (De Roest 2008:34). With regard to the diverse motives for making a commitment to the church (or for not doing so), De Roest (2008:37) quotes Stoffels, who remarks that, without some form of subjective appropriation and experience of faith, the development of any strong ties to the church is unlikely. De Roest (2008:37) then elaborates on another variation of this theme by pointing out that secularisation within the church, where people cling to church attendance and church rituals without any fundamental experience of personal faith, will ultimately lead to the weakening of these ties and possibly to a permanent departure from the Christian faith. De Roest adds that, even in cases where a person who has departed in this way experiences a renewed religious longing, it is not an easy matter for him to return to the God to whom he has bidden farewell.

The majority of the respondents (54%) had migrated from a Dutch Reformed congregation. Although there is an explanation for this, it still remains a phenomenon of which cognisance should be taken. It is equally significant that the majority of the respondents (74%) had only changed congregations once.

6.3 The nature and functioning of congregations as an influence on migration

The provisional assumption that the reasons for migration probably lie in factors that are inherent to the nature and functioning of congregational activities, seems to be true - at least in tentative terms, and at least in respect of those factors that motivated respondents to move from their previous congregation, i.e., the 'push' factors. Yet why is it that - despite "problems" ('push' factors), dissatisfaction with previous congregations and the shrinking of congregations for reasons other than the demise of members, the declining birth rate, and emigration to other countries -many Christian congregations still continue to grow? What are the drawing forces - the 'pull' factors - that cause members to migrate to 'another' congregation in spite of, for example, De Roest's projections regarding the nature of congregations or faith communities of the future, in terms of his models of the "fishing net", the "inn" and the "temple"?

6.3.1 Consideration of the prospect of migration

Before joining their current congregation, the majority of the respondents had visited it and considered it a prospective congregation (47); had engaged in earnest prayer (31); had held discussions with members of the current congregation (31); had first investigated the "church doctrine" (19), and had held discussions with leaders of the congregation that they wished to join (i.e., their current congregation) (18). Only eight respondents had held discussions with the leaders of their previous congregation. Of the respondents, 56% indicated that they were not influenced in their decision to join the new congregation, but that this had been their own decision. In addition, it is clear that music and singing, the preaching, the hospitality, the way in which the church services were conducted and the spiritual focus were all of great significance to the respondents in their current congregation.

6.3.2 Involvement in congregational activities

With regard to communication as a basis of support, it was interesting to note that 40 responses indicated that involvement in activities provided the best basis of support. Of the respondents, 72% are involved in small-group activities. This corroborates De Roest's assumption regarding the importance of the corporate social context. Heitink, too, echoes a similar sentiment in his exposition of the third function of the church as a community in the formation of a faith community. He calls this function "congregation", which entails the assembled community as the basis of church actions. Burger puts a similar argument forward in his discussion of who and what a community is, and of the identity of a congregation. In order to indicate which 'pull' factors become reasons for migration, we must accept that the new (current) congregation has an appeal value that did not exist in the previous congregation.

6.3.3 Activities in a congregation co-determine the identity of that congregation

What determines the identity, the appeal value, and the drawing forces of the current congregation? According to the responses, the gifts that members can bring to fruition are among these drawing forces. Thus, 21 respondents indicated that they were involved in teaching; 12 that they spoke in tongues, and a further 12 that they were involved in the spreading of the Word. The correlation between questions relating to the gifts is striking. Teaching, speaking in tongues, and the spreading of the Gospel featured to a high degree. All (100%) of the respondents indicated that their current congregation reaches out to those in need - another aspect that serves as an identity factor. Of the respondents, 86% indicated that they themselves had experienced support from the congregation in times of need, but only 46% were themselves involved in reaching out to those in need.

The respondents experience the identity of the current congregation in a positive way, so much so that 98% are prepared to invite a family member or friend to a worship service. The considerations that are deemed important by respondents in their identification with a congregation, are probably related to the core of the experience of faith in a congregational context, and can, therefore, be regarded as being co-determinative for the identity of the congregation - and thus, as potential 'pull' factors. The reasons for migration would thus be very strongly influenced by these considerations. For respondents, the acceptance of the authority of the Bible (98%), preaching that is in line with Scripture (90%), the administration of the sacraments (86%), missionary and outreach actions (94%), evangelisation actions (92%), and the relief of poverty (78%) are important. On the basis of the foregoing, the three most important considerations were identified, namely preaching that is in line with Scripture, the authority of the Bible, and evangelisation.

The current congregation had a strong motivating influence on the respondents in respect of attendance of church services (98%); commitment to congregational activities with a view to spiritual growth (92%), and personal spiritual growth (96%). Burger's two observations warrant mention at this point. The relationship between Christ and His congregation is a unique relationship that overshadows all others. Moreover, it is an exclusive relationship: if we say "Yes" to God, this also comprises a "No" to all other relationships that would demand a monopoly of our hearts (Burger 1999:56). The Lord has the right to this exclusive relationship between ourselves and Him, because He has saved us (Burger 1999:57). He loves His people and wants them to love Him (Burger 1999:58). In addition, the congregation proves their love by their obedience in doing His will; love that finds expression in actions (Burger 1999:60). Of fundamental importance is the assumption that the congregation should be regarded, in its totality, as a primary instrument that the Spirit wishes to use in His work on the communication of the gospel (Burger 1999:107). Burger (1999:108) points out that the credibility of the ministry and witness of the congregation are related to the integrated and consistent witnessing of the congregation, which means that what the community is, what it says (or confesses), what it does, and what it prays should all be congruent (Koinonia = is; Kerugma = says; Diakonia = do; Leitourgia = pray). Burger (1999:108) does not underemphasise the role of individuals or of the regional or ecumenical church. As a matter of fact, he makes it abundantly clear that the work and witness of the members of the church and congregation are more important than had been supposed. The ministry belongs to the congregation, in other words, the ordinary members of the congregation. He points out that the model provided in Ephesians 4 of the congregation's office as the equipper of the congregation in its work of service, is the correct one. He points out that it is necessary to move away from a narrow understanding of the ministry as a mere administration of the offices of the church to the congregation, towards a broader interpretation of that commission as a ministry of (and by) the congregation to the world - in which the offices of the church play a guiding, equipping and empowering role (Burger 1999:109).

The foregoing emphasises the core and essence of the Christian congregation. If there is a high consensus regarding the priority thereof in a congregation, this should be regarded as a decisive reason for migration (a drawing force or 'pull' factor).

6.3.4 Faith, congregational activities and involvement

The questions regarding the degree to which the church services and congregational activities of the current congregation assist the respondents in their daily lives, repeatedly displayed a high response rate in the "To a large extent" category. This, in fact, serves as an endorsement of Burger's standpoint, as set out earlier. If the congregation does not accept co-responsibility for the empowerment and equipping of congregation members for their daily lives, then it has failed in its task as a congregation. Where such responsibility is, in fact, accepted and honoured, this comprises a reason (drawing force) for migration. Stoffels's standpoint, quoted by De Roest (2008:37), warrants mention at this point. Stoffels asserts that, without some form of subjective appropriation and experience of faith, the development of a strong bond with the church is unlikely.

De Roest (2008:39) also points out that the stability and durability of Christian convictions and motivations requires a collective social context - a corporate body of Christians.

According to sociologists, a faith that is functional and satisfying cannot be successful outside of the church. Religious experiences will not take root if they are not supported by a community of co-believers.

According to De Roest, taking hold of, and experiencing the faith is thus a prerequisite for a strong bond with the congregation. The respondents experience this personal faith by means of a spiritual relationship with other members of the congregation, thereby forming a bond with the congregation. From this, it is clear that respondents identify with the statement that they changed to another congregation with a view to becoming closer to God and entering into a deeper spiritual relationship with fellow believers. Their experience of faith is also reflected by the fact that they regularly engage in personal prayer and Bible study, participate in home prayer meetings on a fairly regular basis, attend services regularly and base their views on Scripture on the acceptance of the authority of the Bible. This is further underscored by the response to the question regarding religious conviction and the moment of dedication and conversion: 98% of the respondents indicated that they had, in fact, had such an experience. Spiritual growth on a personal level is thus mediated by the congregation (by means of, inter alia, church services); it is practised by the individual (through times of personal prayer, inter alia), and it is embodied in the community of the faithful and in congregational activities. Collectively, this becomes the "spiritual home" of the congregation member. Where such a situation prevails, a magnetism - a drawing force (pull factor) - arises as a decisive reason for migration.

The above assumption is strengthened by the responses to the question, "Do you agree or disagree: 'My spiritual needs are satisfied by my new congregation'?" Jointly, the options "Definitely agree" (65%) and "Agree" (30%) registered a positive response of 95%. This outcome confirms the argument put forward in the previous paragraph. The responses confirm the migrants' involvement in their current congregation, and indicate a high degree of informedness and shared experience. Their "being at home" is not a passive Sunday experience, but has (probably), to a large extent, become a way of life.

From the above, it is clear that the reasons for migration can, in fact, be identified, namely not feeling at home in the congregation; the need for spiritual growth, and traditionalism (stiffness and formality), and that the repelling and drawing forces (push and pull factors) can, to a large extent, be determined. The push factors are those mentioned earlier, while the pull factors pertain to the question of who and what the current congregation is, as embodied in the identity, the personal experience of faith, the congregational mediation and empowerment, as well as the congregational activities, as directed by the mission and goal of the congregation.

Given this scenario, the question arises as to why congregations have historically shrunk and even disappeared, and why some congregations have stagnated. The answer can at least partly be traced in the following terms: De Roest points out the decline in the former tendency towards involvement and identification with a single institution and, along with this, the loss of a lifelong institutional "commitment" (De Roest 2008:26), as well as the loss or absence of a personally experienced faith (De Roest 2008:37). Migliore (2004:250) identifies four core problems that people have with the church, namely individualism, privatisation, the church as a bureaucratic organisation, and the tension between the expressed beliefs of the church and its actual practices.

The effects of secularisation and the Enlightenment, and their consequences at various levels, have been pointed out earlier. The impact of man's so-called "autonomy" on faith and on the church has been dramatic. The effects of "inculturation" pose a challenge that is applicable to every congregation everywhere. The question posed earlier on once again comes to the fore at this point: Do the factors of individualism, secularisation, materialism and postmodernist tendencies influence migration between congregations? If so, how?

Heitink's premise is significant, since the phenomenon of migration -and particularly the fact that the recruitment capacity of congregations (in order to give effect to the Christianisation process) has, in many instances, merely degenerated into a process of recruiting people from other congregations - gives rise to the question of whether the occurrence of migration is not perhaps a wake-up call to both the previous and current congregations of migrants, as typified by the respondents; a clarion call to determine the impact of culture (both congregational and societal) on the nature and functioning of congregations, and also to determine whether adaptation has occurred, and whether "inculturation" is receiving the attention that it warrants.

On the basis of the theories of McDonaldisation and Consumerism, as well as of the relevance of both theories, it can be inferred that both phenomena are fundamental, not only to globalism, but also to postmodernism in the broadest sense thereof. In addition, the impact and relevance thereof for the congregation, for the member and for Practical Theology can be spelled out on the basis of Erre's work on McDonaldisation. Erre indicates that research has already demonstrated the influence of McDonaldisation on the congregation, including, inter alia, the influence of the principles of efficiency, calculability and predictability. Conradie analysed the influence of consumerism, as expounded by Baudrilland and Ritzer, in terms of its impact on the church and congregation. What is, in fact, important, is to indicate that McDonaldisation and Consumerism are fundamental to all facets of the spirit of the time - postmodernism - including individualism, the autonomous, independent human being, secularisation, and neo-materialism.

The impact of McDonaldisation on congregational life, along with the relevance of this factor for congregations, has already been pointed out. Its relevance to migration is equally important. Respondents indicated that they had held discussions with the spiritual leaders before joining their current congregations (36%), as well as with members of the congregation (62%). This raises the issue of control - a principle of McDonaldisation. In this regard, Erre (2009:36) has the following to say:

Very often our version of following Jesus gets held up as the only way to do it, and those who do differently are rarely welcomed. Power and control undergird a lot of the ways we as pastors lead our churches.

Critics may be of the opinion that the percentage of respondents who held discussions with spiritual leaders is too insignificant to draw this conclusion. However, the responses that typify the leadership style of the spiritual leaders indicated that the leaders display a kind of leadership that inspires people to act (64%); in other words, strong leadership. These leaders are thus able to influence people. Similarly, all the other principles of McDonaldisation can be highlighted, and their relevance for migration clarified. The same applies to Consumerism, as analysed by Conradie.

To the same degree that the Consumer culture is impacting on religion, namely in terms of the commodification of religion; the commercialisation of the church; variation in congregational activities; the Gospel in the media, and the fact that people's concept of the church and of faith is influenced by the consumer culture, the above arguments also apply to migration. Religion is being restricted to the private living context of the individual, and decisions relating to congregational migration have become the decisions of the autonomous, independent individual.9

In this regard, it should be borne in mind that migration does not only occur out of congregations, but also into congregations, and that push and pull factors are valid in both instances, to a greater or lesser extent. What can thus be inferred is that all congregations should probably take account of the spirit of the time, and of paradigm shifts. In terms of their mission, all congregations will thus probably also need to take cognisance of adaptation ("inculturation").

The question can now be asked as to whether migration is the result of the nature and functioning of congregations themselves. The answer is not as simple as the responses initially seemed to indicate, in the sense that two tendencies can be identified: push factors that activate the tendency to move out of the previous congregation, for example, poor preaching, and a drawing or 'pulling' tendency representing those factors that attract people, for example, "feeling at home" - i.e., pull factors. On the basis of the questionnaires and the interviews, it is clear that, first - although only one single reason is cited - a multiplicity of factors often simultaneously play a role and, secondly, that many of these factors are peculiar to the individual respondents themselves, and have little to do with the congregation. This is reflected, in particular, by the question pertaining to the "lack of love", which registered the fourth highest number of responses, namely 11. If the congregation functions on this basis, it belies the most basic principle of the Gospel, namely the commandment to "love your neighbour as yourself". Should this, in fact, be the case, the question should be asked: To what degree does this not perhaps represent an extremely subjective observation? However, the fact remains that this was the observation of the respondents, and that it was registered as such. Lastly, as noted earlier, the spirit of the time (postmodernism) also plays a role, and will probably play a still greater role in the future in the South African context.

In light of overwhelming evidence gleaned from the questionnaires and the interviews, it can be stated that the reasons for migration can, in fact, mainly be traced in the nature and functioning of the congregation, and that clear tendencies can be identified in terms of push and pull factors. It is obvious that this phenomenon holds implications for both the institutionalised church and the community of believers (as also confirmed in the findings made by Church Mirror).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Babbie, E. & Mouton, J. 2005. The practice of social research. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Baudrillard, J. 1998. The consumer society, myths and structures. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Burger, C. 1999. Gemeentes in die kragveld van die Gees. Stellenbosch: Buvton. [ Links ]

Conradie, E. 2009. Uitverkoop? In Gesprek oor die verbruikerskultuur. Wellington: Lux Verbi. [ Links ]

De Roest, H. 2008. En de wind steekt op: Kleine ecclesiologie van de hoop. Zoetemeer: Meinema. [ Links ]

Erre, M. 2009. Death by church. Eugene, OR: Harvest House Publishers. [ Links ]

Glock, C.Y. & Bellah, R.N. (Eds) 1967. The new religious consciousness. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Glock, C.Y., Ringer, B.B. & Babbie, E. 1967. To comfort and to challenge. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Hanekom, B. 2014. Ontevrede lidmate is nie 'n probleem nie. Rapport, 19 Januarie, p. 3. [ Links ]

Heitink, G. 1993. Praktische theologie, geskiedenis, theorie, handelingsvelden. Kampen: Kok. [ Links ]

________. 2007. Een kerk met karakter: Tijd voor herorientatie. Kampen: Kok. [ Links ]

Henning, E. 2011. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. [ Links ]

Hill, M. 1973. A sociology of religion. London: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Hunt, S.J. 2003. Alternative religions: A sociological introduction. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Company. [ Links ]

KERKSPIEËL 2010. Unpublished report to the General synod of the DRC. [ Links ]

Migliore, D.I. 2004. Faith seeking understanding: An introduction to Christian theology. 2nd ed. Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen, J. 2014. Krisis kom vir leë kerke. Rapport, 12 Januarie, p. 7. [ Links ]

Pretorius, W. 2014. Kerk groei op ander maniere. Rapport, 26 Januarie, pp. 4-5. [ Links ]

Ritzer, G. 2007. Contemporary sociological theory. The basics. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Schoeman, W.J. 2011. Kerkspieël - 'n kritiese bestekopname. NGTT 52(3&4), September & December:472-488. [ Links ]

________. 2012. Op soek na gemeentes met integriteit: Die bydrae van C.W. Burger. NGTT 53(3 & 4), September & December:302-311. [ Links ]

Zubaida, S. 2009. Islam, the people and the state: Political ideas and movements in the Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris. [ Links ]

1 Read: "the changing of members' church affiliation".

2 Part of this article is based on "Redes vir die migrasie van lidmate van een gemeente na 'n ander - 'n praktiese teologiese studie by enkele Bloemfonteinse Christen gemeentes", an unpublished MTh dissertation, Bloemfontein: University of the Free State by I.M. Bredenkamp, 2014.

3 Church Mirror is a research document of the DRC, published in Afrikaans under the name Kerkspieël.

4 Doxa Deo, Fichardt Park; A.G.S. Siloam, Universitas, and the Baptiste Kerk [Baptist Church], Langenhoven Park.

5 The concept of a 'member' varies, to some extent, from congregation to congregation, and amounts, in the majority of cases, to the making of a personal confession, linked to voluntary 'faith formation'.

6 This cultural schism should probably be regarded as having a broader application than the Dutch context alone (cf. Glock & Bellah 1976:299-310).

7 In this instance, to a very great extent and to a large extent are often grouped together. To a very great extent indicates the high intensity that a respondent associates with a response, while to a large extent indicates this to a lesser degree. To a fair extent may suggest a certain degree of doubt.

8 The concepts of 'push factors' and 'pull factors' are not used in an absolutely exact sense in this instance. 'Push' factors would refer to those aspects ranging from less positive to definitely negative that are associated with a congregation, and which may represent reasons for migration. 'Pull' factors would represent the more positive aspects associated with a congregation, comprising reasons for migration to such a congregation.

9 Cf. the question: "Who influenced you in respect of the choice of a new congregation?" and the answer: "My own decision" (56%) - the highest percentage of all the responses.