Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Theologica

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.35 supl.22 Bloemfontein 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v21i1.8s

Identity and community in South African congregations

W.J. Schoeman

Dept. Practical Theology, University of the Free State, South Africa. E-mail: schoemanw@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The religious identity of both worshippers and congregations is not static, due to a changing context. Do congregational members believe, belong and engage in the same way as they did previously, or is it possible to track certain changes? Two Congregational Life Surveys were conducted in 2006 and 2010 among the membership of Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) congregations. The two surveys suggest that attenders prefer a private expression of their religion in which the Bible plays an important role. They have a strong bond with the congregation, but the preferred role of the congregation is to provide in the spiritual needs of the attenders. The engagement with the community is not so important for the attenders; in fact, the majority of them are not involved in the community. They value what the congregation does in the community, but personal involvement does not receive much attention. The biggest challenge for the reformation of a religious identity for both the membership and congregations of the DRC is to be more contextual and engaged in their social environment and culture. The two surveys suggest a movement in the opposite direction.

Keywords: Congregations, Religious identity, Congregational Life Survey, Dutch Reformed Church, Community

Sleutelwoorde: Gemeentes, Godsdienstige identiteit, "Congregational Life Survey", Nederduits Gereformeerde Kerk, Gemeenskap

1. INTRODUCTION

Identity describes who I am and who we are: both are socially formed and influenced by religion. The religious identity of both worshippers and congregations is not static; this is not possible in a fluid and transforming context (Joubert 2013:116-117). This article aims to seek changes in the formation and redefining of religious identity in reformed congregations and among their membership. "Understanding a congregation requires understanding that it is a unique gathering of people with a cultural identity all its own" (Ammerman et al. 1998:78). Do congregational members believe, belong and engage in the same way as they did previously, or is it possible to track some changes? Two Congregational Life Surveys (CLSs) were conducted in 2006 and 2010 among the membership of Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) congregations. What can be learned by analysing and comparing the results of these two surveys?

A changing virtual, socio-political and economic environment poses new and exciting challenges to congregations. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, three processes saw the development of a new society: information technology; the socio-economic restructuring of capitalism and the state, and the cultural and social movements that emerged in the Western world (Castells 2000a:694). Given the South African context, is it possible to identify certain markers, if any, in the reformation of a religious identity and the consequences thereof for congregations? The contextualization of faith practices asks for the re-evaluation of congregational life, identity and the congregation's role in the community (Brouwer 2008:59). The empirical results from these two surveys will be used to explore and rethink the identity and role of DRC congregations within the South African context.

The South African religious landscape is part of a changing world. Changes are inevitable in a dynamic and fluid world; this holds true for the South African society that moved from a racially divided society to a more open society, at least in terms of a new constitutional framework. The position and role of religion are not the same as a decade or two ago. Religious institutions are part of civil society, but they have a marginalized voice. Individual members find themselves within this context and must also redefine their own positioning.

2. THE RELIGIOUS IDENTITY OF CONGREGATIONAL MEMBERS

Religion is a multidimensional phenomenon, and it is possible to identify different dimensions or facets of religion. For example, a distinction can be made between beliefs, practices (or behaviour), and affiliation (or identification) (Saroglou 2011:1321). The interaction and relationship between religion and identity is an important theme for congregations and their members. The provision of meaning and belonging are two important functions of religion and, therefore, also for the formation of people's identity. Identity helps describe who a person is, and religion is part of this defining process (Greil & Davidman 2007:549). In addition, religious identity has a social dimension; religious institutions help shape the social identity, membership and belief systems of a group (Ysseldyk et al. 2010:61). As a social group, a congregation plays an important role in the formation of the religious identity of its members. Congregations create spaces for the formation and development of religious identities.

The concept of identity refers to a person's self-conception, social presentation and, more generally, the aspects of a person that make him/her unique, or qualitatively different from others. "As a very basic starting point, identity is the human capacity - rooted in language - to know who's who (and hence what's what)." (Jenkins 2014:6). Identity is the construction of meaning through the actions of social actors and it makes use of the materials of experience, experience that is both historical and collective and/or individual (Castells 2000b:6-7). This identifies 'me' and the 'other' not in a simplistic, but in a multidimensional manner. Identity may be defined as the distinctive characteristic belonging to any given individual, or shared by all members of a particular social category or group (Johnson et al. 2010:149-150). Personal and communal identity is thus best described both relationally and contextually. Identity matters, "... because it is the basic cognitive mechanism that humans use to sort out themselves and their fellows, individually and collectively" (Jenkins 2014:14). Identity is also formed within a social context.

Social identity can be regarded as part of an individual's self-image, and stems from belonging to a particular group. Social identity has three facets: cognitive (recognition of belonging to a group), evaluative (the value attached to belonging to the group), and emotional (attitudes towards insiders and outsiders) (Baker 2012:130). From a social perspective, the formation of an identity is part of a social construction process. The different roles that a person plays contribute to the development of a social and religious identity. Individuals are seeking individualized meaning and are, therefore, working with shifting and multiple identities (Greil & Davidman 2007:551-558). They are constructing their own identity as part of a personal narrative within a social environment.

In the formation of an identity, social groups play a significant role and, for the same reason, a congregation should play a notable role in the formation of its members' religious identities. In the formation of a social identity, it is important to find a balance between motivation for individual uniqueness and belonging to a group (Ysseldyk et al. 2010:62). As a belief system, religion helps individuals identify with a religious group. Consequently, religion has cognitive and emotional value for the membership of the group or congregation (Ysseldyk et al. 2010:68). The interaction between the members and the congregation helps construct a religious identity of both the individual and the congregation.

Religious identity formation takes place within a specific context and, in this regard, the congregation is part of this context. Different aspects may be identified to describe a congregational identity: it is explicit and shared; it enhances loyalty and commitment; it gives direction to action, and it provides certain boundaries. It includes values, a shared history and heritage, and is part of a congregational culture (Woolever et al. 2006:53). Congregational identity is contextual:

Not only are congregations and their memberships clearly located within social structure, they are also dynamic entities within it, operating within the processes of social and system integration and differentiation (Stringer 2013:29).

The social networks, relationships and interaction within a community impact on the way in which a congregation is functioning. This makes a congregation part of the local environment. The social structure of a community lies at the heart of the congregational dynamics (Stringer 2013:34; Brouwer 2008:50). The degree of interaction between the community and the congregation affects the contextual presence of the congregation and, consequently, the formation of its members' religious identities.

Although different concepts may be used to describe the religious identity of the congregational membership, three of these concepts, namely believe, belong and engage, are relevant to this research. The element of believing implies specific religious beliefs and are mostly based on a cognitive meaning-making process (Saroglou 2011:1326). This element is characterized by religious ideas, beliefs, norms and symbols.

Belonging may be described as an element of bonding to a group, an emotional aspect of religion that facilitates experience and rituals. It may occur in private (prayer and meditation) or in public (worship and religious ceremonies) (Saroglou 2011:1326). Belonging includes ". authority, narratives and symbols to maintain cohesiveness and enhance a positive social identity and collective self-esteem" (Saroglou 2011:1327). Belonging to a congregation provides safety, security and stability to its members (Ysseldyk et al. 2010:62). Religion binds people together in cooperative communities (Graham & Haidt 2010:140), and it is important not only to scrutinise the belief system, but also to strengthen a community, in this case a congregation.

In addition, religion has the function of engagement and involvement in the wider community. "Religion is an important source of values of benevolence and civic engagement." (Guo et al. 2013:35). The community engagement or lack thereof affects the formation of the religious identity of its membership.

Measuring the above three concepts (believe, belong and engage) is complex, and there is no integrated measure of the religious dimensions available (Saroglou 2011:1334). The Church Life Survey (CLS) results will be used to describe these three concepts as indicators or markers of the religious identity of the members of DRC congregations. This will not give a comprehensive answer, because the formation of a religious identity is a dynamic and complex process.

3.THE METHODOLOGY OF THE 2006 AND 2010 CHURCH LIFE SURVEYS

The first CLS was conducted in 1991 in Australia with the aim to describe congregational life by listening to the voice of worshippers. The success of the survey caused it to be used in New Zeeland, England and the United States. In 2001, approximately 1.2 million worshippers in these four countries participated in the International Congregational Church Life Survey (see Bruce et al. 2006). The CLS questionnaire was used in the DRC surveys. In 2006 and 2010, a random sample of 10% was selected from the DRC congregations. The response rate was 81% in 2006 and 75% in 2010.

The aim of this article is to use the three concepts, namely believe, belong and engage, as a lens to scrutinise the data available from the two DRC surveys. The relevant questions selected from the questionnaire will be discussed at the beginning of each of the following sections. The CLSs also categorize the different questions into strengths. In this article, three strengths are selected and used as a lens: growing spiritually, participating in the congregation, and focusing on the community. The findings of the above strengths from the 2006 and 2010 surveys in the DRC are compared with the fastest growing congregations in the Presbyterian Church (USA) 2011 (Bruce et al. 2012). This comparison has certain limitations in terms of the contextual and ecclesiological differences between the two denominations, but it is useful as a reference point to identify certain trends by comparing the strengths.

4.BIOGRAPHICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE ATTENDERS

The sample population for the 2006 and 2010 surveys has the following characteristics:

- The worshippers are older: in 2006, 37% were aged over 60 and, in 2010, this increased to 40.2%. In 2010, more members were aged over 60 than members younger than 16 years.

- The majority of the members (58%) are female.

- The majority of the members (53.3%) are employed (part- and full-time).

- Education: 51.7% have a tertiary education (55% in 2006).

- Marital status: First marriage - 60.6% (2006 - 63%). Living in a committed relationship - 2.1% (2006 - 1%); this has doubled in 4 years.

- 99.2% of the members are White.

- Description of the household: Two or more adults with child/children -44.4%; this could be described as the 'traditional' family. Single persons and couples without children comprise 37.7% of the sample population.

- Although the members' financial contributions came under pressure, those members who give more than 10% of their income increased from 2006 to 2010; the majority of the members give between 5% and 9% of their income (32.6% in 2010 and 34% in 2006).

In summary, the sample population could be described as mostly female, White, married, middle class, employed, and with a good education. The most notable change between 2006 and 2010 was the increase in single members and in those living in a committed relationship.

5. WHAT DO THE ATTENDERS BELIEVE?

The belief system of the attenders is conceptualized in terms of the following aspects:

- Private devotional activities. How often do you spend time in private devotional activities such as prayer, meditation, reading the Bible alone?

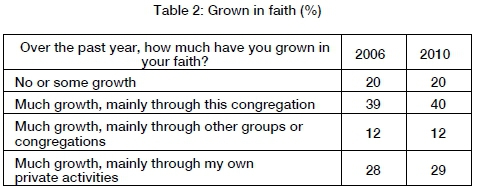

- Growth in faith. The role of the congregation, other groups or congregations and private activities are investigated with respect to the attenders' growth in faith.

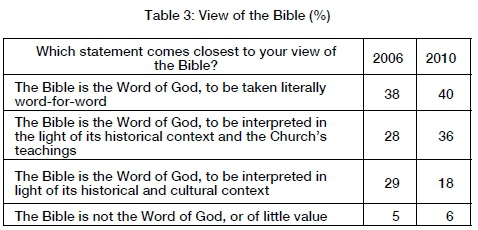

- View and interpretation of the Bible as the Word of God and the role of the historical context and teachings of the Church in the interpretation of the Bible.

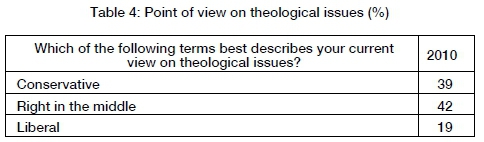

- Current theological approach of the attenders. Conservative or liberal?

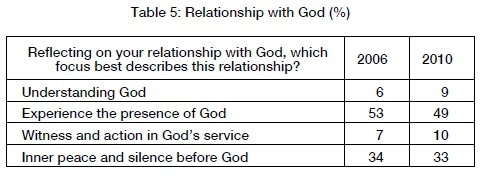

- The relationship with God is described in terms of understanding, experience, action, and inner peace.

These aspects are used as markers to describe the belief system of the attenders in terms of this empirical research. This is not a comprehensive list, but it provides a framework to describe what the attenders believe.

Daily private devotional activities such as reading the Bible, prayer and meditation play an important role in die religious life of believers. These private devotional activities are increasingly important for attenders (Table 1).

The majority of the attenders (81%) reported that they had experienced much growth in their faith over the past year (Table 2). This growth happened mostly through the activities of the congregation (40%) and their own private activities (29%). Private devotional activities are important, but the role of the congregation in the growth of the members cannot be ignored.

The majority of the believers regard the Bible literally (Table 3). The second and third statements leave room for interpretation in terms of historical context and the Church's teachings/cultural context. From 2006 to 2010, the increase in terms of the second statement point to an increase in the role played by the teachings of the Church. The critical question in this regard would be: Is there room for a discernment process in the understanding of the Bible?

Most of the attenders are in the middle or tend to be more conservative in terms of their current opinion on theological issues (Table 4). The concepts 'conservative' and 'liberal' are not defined, and only reflect the self-understanding of the attender.

In describing their relationship with God, the attenders emphasise 'experience the presence of God' (Table 5). The second most important focus is on 'inner peace and silence before God'. This could be considered part of an individual devotional ritual.

The Bible plays an important role in the belief system of attenders who read it on a weekly basis, and understand it literally, probably from a more conservative perspective. The changes from 2006 to 2010 indicate a more private expression of the attenders' religious life. Belief is about a regular engagement with the Bible where the experience of God and inner peace and silence play a distinctive role. On the other hand, the role of the congregation in the growth of the faith of attenders cannot be disregarded. This is an indication not only of a vertical expression of faith, but also of the social dimension of faith.

6. HOW DO THE ATTENDERS BELONG TO THE CONGREGATION?

There is a social aspect to religion that finds expression for attenders in their relationship with the community of believers or the congregation. Belonging to the congregation is described in terms of the following aspects:

- Frequency of attendance of worship services.

- Involvement in the congregation's group activities

- Spiritual needs of the attenders are met in the congregation.

- Involvement in the decision-making process of the congregation.

- The strength of the bond between congregation and attender.

These variables give an indication of the relationship between attender and congregation and do not claim to be an exclusive list of all the variables in this regard.

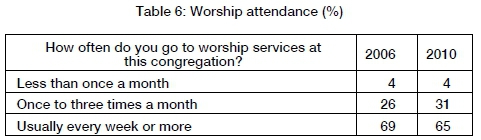

In comparing the attendance patterns between 2006 and 2010, there is an increase in the attendance of monthly worship services and a slight decrease in the weekly attendance (Table 6). Over 95% of the attenders attend a worship service on a monthly basis or more.

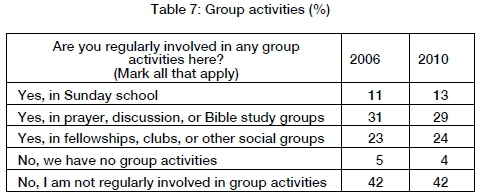

Small group activities play an important role in the participation of members in the congregation (Table 7); over half of the members are, to some extent, involved in small group activities. This involvement remained approximately the same from 2006 to 2010.

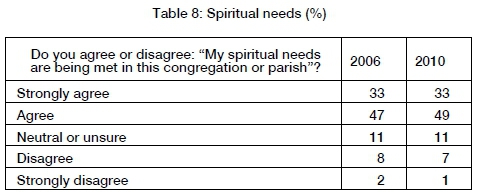

Over 80% of the attenders agree or strongly agree that the congregation meets their spiritual needs (Table 8). There is a slight increase from 2006. The role played by the congregation cannot be ignored, but the attender's personal and spiritual needs are paramount.

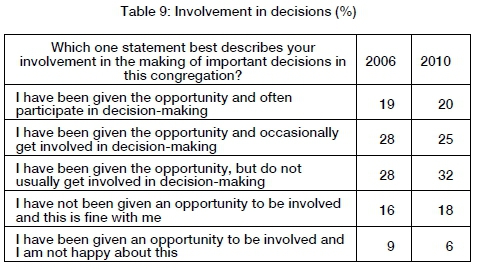

Over half of the worshippers do not get involved in the decision-making process of the congregation, but are also satisfied therewith (Table 9). Given the opportunity (75%), they only get occasionally (25%) involved in the decision-making process of the congregation. A critical question could be: Does this imply that it is not important to be involved in the processes or that there is no trust in the leadership of the congregation? Only 6% are not given the opportunity and are not satisfied therewith.

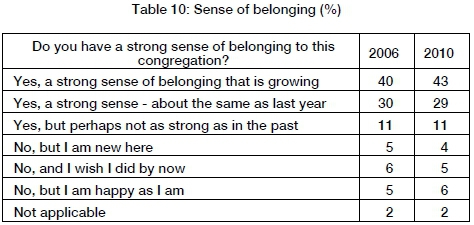

The majority of the worshippers (80%) report a strong bond with the congregation, and 43% report that this sense of belonging is also growing (Table 10). The growing sense of belonging is better in 2010 than in 2006.

What conclusions can be drawn on the relationship between attender and congregation? Between 2006 and 2010, the extent of the relationship between attender and congregation remained, to some extent, the same. There is a strong bond between attender and congregation, as the congregation plays an important role in the religious life of attenders. The key to understanding this relationship may be in the role that the congregation plays to meet the personal spiritual needs of the attender. If this is considered in conjunction with their private devotional life, it may point to a more personal and private expression of religion. The involvement of attenders in the decision-making processes of congregations indicates a preference for a more passive rather than active involvement. Are attenders involved in the community, or does this trend point towards a private expression of the individual religion and the congregation's role therein?

7. ATTENDERS' ENGAGEMENT WITH THE COMMUNITY

In light of the previous section, it is thus necessary to enquire about the engagement of attenders in the local community. This can be described in terms of the following aspects:

- Activities of the congregation in order to reach out to the wider community.

- Involvement of attenders in community service or advocacy groups.

- Different activities in which attenders may be involved.

- The value placed by the attenders on outreach activities.

These aspects are only a selection to give an indication of the community engagement of attenders; it is not a comprehensive list.

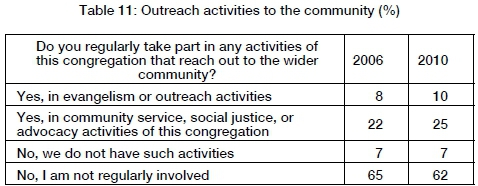

Are attenders involved in activities of the congregation in the wider community? In 2010, they were more regularly involved in service/social justice/advocacy than evangelism or outreach activities if compared to the data for 2006 (Table 11). On the other hand, approximately two-thirds of the attenders are not regularly involved in these types of activities.

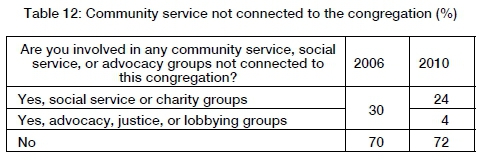

It may be that attenders are engaging with the community outside the normal activities of the congregation. Seventy-two per cent are not involved in such activities (Table 12). In 2010, more were involved in social service or charity groups than in advocacy, justice and lobbying groups. There is less involvement in more activist activities.

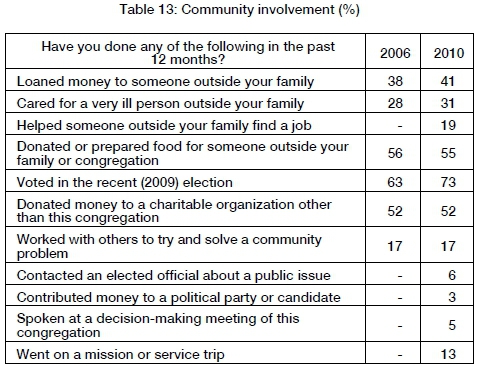

Where are the attenders involved in the community or what are they doing in the community? The five most reported outreach activities are, in order of preference, (Table 13):

1. Voted in the recent election.

2. Donated or prepared food for someone outside their family or congregation.

3. Donated money to a charitable organisation other than this congregation.

4. Loaned money to someone outside their family.

5. Cared for a very ill person outside their family.

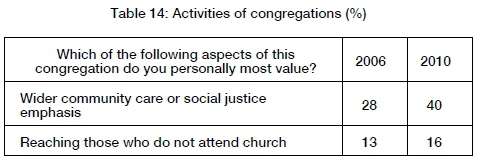

There is a tendency to value more the involvement of the congregation in the community. This increased from 41% in 2006 to 56% in 2010 (Table 14). Attenders value the congregation's emphasis on care and social justice more than reaching out to those who do not attend church.

A few concluding remarks can be made regarding the attenders' community engagement. The most important observation is that two thirds of them are not involved in the community. Those involved consider the following to be the most important activities: to vote in an election; to donate something, or to lend money. Attenders value what congregations do in terms of community involvement, but personal involvement is not a high priority for attenders.

8. COMPARING THE THREE STRENGTHS

The three strengths (growing spiritually, participating in the congregation, and focusing on the community) help one understand and evaluate the attenders' belief, belonging and engagement.

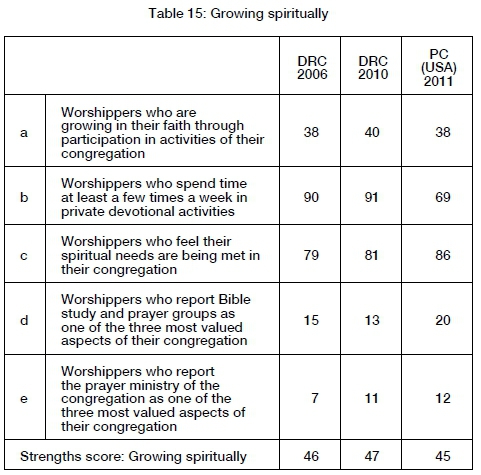

8.1 Strength: Growing spiritually (Table 15)

There is a slight increase, for most of the aspects, from 2006 to 2010. This trend emphasises the growing importance of private devotional activities for attenders. For both 2006 and 2010, the strength scores for growing spirituality are slightly better for the DRC than for the PC (USA). A growing spirituality is important for the membership of the DRC.

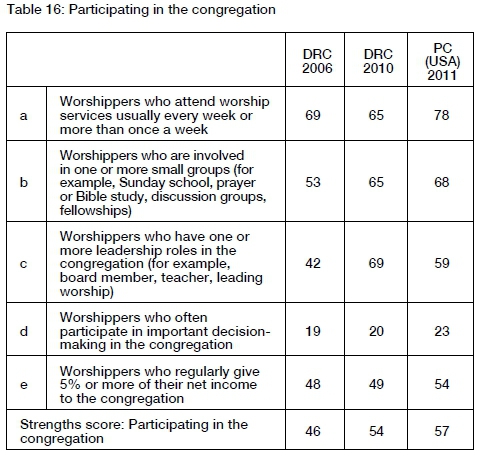

8.2 Strength: Participating in the congregation (Table 16)

There was an increase in the attenders' participation in the congregation from 53 to 65 in the involvement of small groups from 2006 to 2010. Therewas also an increased leadership role for the attenders. The scores for the fastest growing congregations in the PC (USA) are, in most instances, better than those of the DRC. Participation in the congregation (belonging) is not a strength, to the same extent, for the DRC as is growing spiritually.

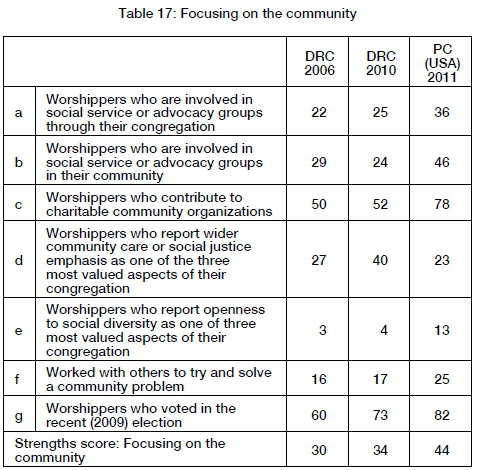

8.3 Strength: Focusing on the community (Table 17)

In the DRC community, care as congregational emphasis and voting in the past election improved from 2006 to 2010. When comparing the DRC with the PC (USA), the former is doing better in 'community care as congregational emphasis'. The PC (USA) is more engaged in all the other aspects of focusing on the community. In the context of this study, there is a difference of 10 points between the 'focus on the community' score of the DRC and the PC (USA). This could indicate that the focus on the community is not as important for the DRC as it is for the PC (USA).

9. CONCLUSIONS

The two CLSs suggest that attenders prefer to privately express their religion, in which the Bible plays an important role. An emphasis on a growing spirituality is, therefore, part of the attenders' individual and private religious identity. They have a strong bond with the congregation, but the preferred role of the congregation is to provide in their spiritual needs. Participating in the congregation is not as important as a growing spirituality. The engagement with the community is not so important for the attenders. In fact, the majority of them are not involved in the community. They value what the congregation does in the community, but they do not pay a great deal of attention to personal involvement. Some studies found that members of mainline churches are more likely to volunteer for social change organizations and are more associated with social activism (Guo et al. 2013:38, 51). This does not seem to be the case for members of the DRC, because independence and autonomy are important aspects of their religious identity:

The more that a moral community is based on ideals of interdependence rather than autonomy, we predict, the more that involvement in such communities will lead to a willingness to part with one's own time and money (Graham & Haidt 2010:146).

A predominantly private expression of religion does not hold well for the attenders' involvement in the community. What would the impact of this be on the congregational identity?

Congregational identity is shaped by the attraction and relationship between its members. They have certain shared preferences. "When its context changes, a congregation with an identity based on affinity may be unable to function effectively in those changed environmental conditions." (Nauta 2007:46). Changes in context and leadership lead to changes in congregational identity, belief, belonging and engagement, which, in turn, lead to changes in the identity of the membership and the congregation. This could be viewed as a strength, not a weakness:

Wherever affinity is expressly understood as the basis of the congregation's own identity, it is easier to openly reflect on what faith means to those who consider themselves part of that congregation (Nauta 2007:51).

The challenge for DRC congregations, in the context of this research, is to use the bonding or affinity within a congregation to move towards greater community involvement.

The ideal may be to have an integrated or uniform identity. However, this is unlikely in an environment where contextualization and inculturation of the gospel is taking place. In this respect, Brouwer uses the concept "hybrid identity" to explain that "identity needs to be negotiated and constructed out of the different parts and those fragments of culture that are still available" (Brouwer 2008:59). Religious identity is, therefore, always under construction and in the process of formation. The concept of koinonia challenges the congregation to develop an inclusive identity that includes and benefits the social and cultural environment (Brouwer 2008:60). A missional preference and inclusive understanding of koinonia could help congregations develop a new identity. However, is this possible?

The development of this new congregational identity should be understood in relation with the local community and its social structure.

Secularization may be understood in terms of declining attendances as a result of declining beliefs, but Stringer's (2013:34) research suggests that it could also be a consequence of the fracture of many urban and rural communities - and thus the end of the social network sets upon which congregational memberships are built. The South African context suggests that the local communities are, to a great extent, fractured due to the apartheid past and the formation of communities and congregations along ethnic and racial lines.

Punt (2009:268) suggests that the biggest challenge for congregations is to be contextual in the formation of a relevant congregational identity. He explains the role of the New Testament texts in this regard:

An appeal to Paul but also to other New Testament documents in favour of a Christian identity devoid of racial or ethnic strains has long been part of the socio-political claim of Christian churches regarding a universal identity reaching beyond racism and ethnicity.

This "universal identity" or a-contextual position leads to the avoidance of societal challenges such as racism and xenophobia. This is the danger of a privatized religious identity:

In the end, and given such considerations about past biblical and current racial stereotyping, it is perhaps not so difficult to understand the troubling paradox that the vast majority of South Africans actively engaging in recent (and current) racist practices and xenophobic attacks, just as readily lay claim to a Christian identity with a strong and avid biblically-based faith (Punt 2009:269).

The biggest challenge for the reformation of a religious identity for both the membership and the congregations of the DRC is to be more contextual and engaged in their social environment and culture. The two CLSs suggest a movement in the opposite direction.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ammerman, N.T., Carroll, J.W., Dudley, C.S. & McKinney, W. (eds.) 1998. Studying congregations. A new handbook. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Baker, C.A. 2012. Social identity theory and biblical interpretation. Biblical Theology Bulletin: Journal of Bible and Culture 42(3):129-138. [ Links ] [Online.] Available from: http://btb.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.1177/0146107912452244 [2014, 22 January].

Brouwer, R. 2008. Hybrid identity. Exploring a Dutch Protestant community. Verbum et Ecclesia 1(1):45-61. [ Links ]

Bruce, D. et al. 2012. Fastest growing Presbyterian Churches. Kentucky: Research Services Presbyterian Church (U.S.A. [ Links ]).

Castells, M. 2000a. Toward a sociology of the network society. Contemporary Sociology 9(5):693-700. [ Links ]

_______. 2000b. Globalisation, identity and the state. Social Dynamics 26 (December 2014):5-17. [ Links ]

Graham, J. & Haidt, J. 2010. Beyond beliefs: Religions bind individuals into moral communities. Personality and Social Psychology Review : An official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc. 14(1):140-150. [ Links ] [Online.] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20089848 [2014, 11 July].

Greil, A.L. & Davidman, L. 2007. Religion and identity. In: J.A. Beckford & N.J. Demerath (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of the sociology of religion (Los Angeles: Sage Publications), pp. 549-565. [ Links ]

Guo, C., Webb, N.J., Abzug, R. & Peck, L.R. 2013. Religious affiliation, religious attendance, and participation in social change organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42(1):34-58. [ Links ] [Online.] Available from: http://nvs.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.1177/0899764012473385 [2014, 11 July].

Jenkins, R. 2014. Social identity. 4th ed. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Johnson, T.L., Rudd, J., Neuendorf, K. & Jian, G. 2010. Worship styles, music and social identity : A communication study. Journal of Communication and Religion 33(July):144-175. [ Links ]

Joubert, S. 2013. Not by dialogue, nor by order or simplicity: The metanoetic presence of the Kingdom of God in a fluid world. Acta Theologica 33(1):114-134. [ Links ]

Nauta, R. 2007. People make the place: Religious leadership and the identity of the local congregation. Pastoral Psychology 56(1):45-52. [ Links ] [Online.] Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11089-007-0098-6 [2014, 22 January].

Punt, J. 2009. Post-apartheid racism in South Africa. The Bible, social identity and stereotyping. Religion and Theology 16 (August 2009):246-272. [ Links ]

Saroglou, V. 2011. Believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging: The big four religious dimensions and cultural variation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42(8):1320-1340. [ Links ] [Online.] Available from: http://jcc.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.1177/0022022111412267 [2014, 11 July].

Stringer, A. 2013. Congregation and social structure: An investigation into four Northern Irish memberships. Social Compass 60(1):22-40. [ Links ] [Online.] Available from: http://scp.sagepub.com/cgi/doi/10.1177/0037768612471775 [2014, 11 July].

Woolever, C., please provide surname and initials of other authors 2006. What do we think about our future and does it matter: Congregational identity and vitality. Journal of Beliefs and Values 27(1):53-64. [ Links ] [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13617670600594335 [2014, 22 January].

Ysseldyk, R., Matheson, K. & Anisman, H. 2010. Religiosity as identity: Toward an understanding of religion from a social identity perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc. 14(1):60-71. [ Links ] [Online.] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20089847 [2014, 11 July 11].

1 Part of this article was delivered by the author as a paper ("Exploring identity and community in congegrations: A perspective from South African congegrations") at the ISSR conference in Tirku, Finland, on 27-30 June 2013.