Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.35 supl.22 Bloemfontein 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v21i1.7s

Empirical research and congregational analysis: Some methodological guidelines for the South African context

M. NelI; W.J. SchoemanII

IDept. Practical Theology, University of Pretoria, e-mail: malannel@up.ac.za

IIDept. Practical Theology, University of the Free State, e-mail: schoemanw@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Empirical research is an inescapable part of responsible congregational analysis. The first question pertains to the value and contribution that empirical research has made to the process of congregational analysis. This article will briefly refer to such contributions. Such analysis can be approached from many different angles and in many different ways. The question remains: Which principles and guidelines should be taken into account when we do such an analysis? On top of all of this is the challenge to do it within the South African context. What should a congregational analysis which will help South African congregations look like? In the search for some methodological guidelines for congregational analysis for the South African context there will, firstly, be a discussion of a number of theological points of departure for a congregational analysis. Following on that will be the methodological guidelines for congregational analysis and, thirdly, guidelines for the South African context will be discussed. The argument in the article ends with a critical reflection of the markers discussed, and a look at the road ahead.

Keywords: Congregational analysis, Empirical research, Methodology, Contextual

Sleutelwoorde: Gemeente analise, Empiriese navorsing, Metodologie, Kontekstueel

Empirical research is an inescapable part of responsible congregational analysis. The first question pertains to the value and contribution that empirical research has made to the process of congregational analysis.

This article will briefly refer to such contributions. Such analysis canbe approached from many different angles and in many different ways. The question remains: Which principles and guidelines should be taken into account when we do such an analysis? On top of all of this is the challenge to do it within the South African context. What should a congregational analysis which will help South African congregations look like?

Congregations are contextual realities. While the Church and congregations are at the same time a theological and cosmological reality, it is in particular a geographical and contextual reality. Congregations have addresses and are, for that reason, not abstract entities. They have been called by the Holy Trinity and put in a specific place; therefore it concerns text and context (Van Gelder 2007:104-107). Within this geographical context they participate in the recreation. To escape this, using whichever pious arguments, is actually the participation of congregations in an irrelevant journey which does not serve the kingdom. As a new and spiritual creation all involvement is firstly contextual, inter alia because of the fact that to be human is to be local. Despite global connections and networks (virtually every moment) being human is locally bound. Congregations, like people, can only 'be' local - here and now. Identity is at the same time local and global, but contextually first and foremost local. Congregations only have missional integrity when they are contextually relevant (Nel 2011 e).

In the search for some methodological guidelines for congregational analysis for the South African context there will, firstly, be a discussion of a number of theological points of departure for a congregational analysis. Following on that will be the methodological guidelines for congregational analysis and, thirdly, guidelines for the South African context will be discussed. The argument in the article ends with a critical reflection of the markers discussed, and a look at the road ahead.

1. GENERAL THEOLOGICAL POINTS OF DEPARTURE FOR A CONGREGATIONAL ANALYSIS.

Why is empirical research an indispensable tool for congregational analysis? Various reasons can be presented, but the following theological and empirical reasons serve as motivation for congregational analysis.

1.1 No congregation has become what it already is in Christ. The identity of being is already in Christ valid. There is no need to become who we 'are'. The eternal calling for congregations is to become what they already are in Christ. This is described in many multi-coloured metaphors. This is what congregations are involved with, admittedly some in a more purposeful manner. At times it seems that certain congregations have made peace that they are not becoming who they already are in Christ. Others resist this purposefully. They have declared the past as the objective and for them the past is better than the future.

Change motivates the renewal of the congregation or, according to the terminology of many, the development of a missional congregation. This phase of 'motivation' is a basic theological and constant phase in the process of congregational renewal (Nel 1994:125-147). This reformative calling motivates and informs the process. It is, however, also a process which questions why and where reformation is required. In the growth of a congregation it is essentially concerned with reformation changing towards God's purpose and the calling of the congregation. A given or defined identity requires a lived identity and this lived identity may also be described as the empirical identity of a congregation (Nel 1998:37). Congregational growth is concerned with the change and renewal of both identities. In the case of congregational analysis it is, in particular, concerned with the research of an empirical identity of a specific congregation (Nel 2015:256-257).

1.2 It is precisely the empirical reality of the congregation which brings the voice and context of the local religious congregation into play. In consideration of the congregational ecclesiology the empirical reality also comes into play, as the 'sources' are more than just the Bible. How the congregation, as creation of God, understands and uses the Bible plays a decisive role. The same text also plays a role in analysis, but there is another text which should be considered. A religious congregation, as the creation of God, has its genesis and functions - in a specific context and time. How they understand themselves and how they in this genesis give form to their given identity is relevant. The question is not so much why the analysis is necessary, but which guidelines and principles are relevant. An analysis of the congregation as text within context is as necessary as, for example, the exegesis of the Bible text for a sermon. Both take place within a hermeneutic framework dealing with text and context (Hendriks 2004:19; Van Gelder 2007:104-114).

1.3 What is happening in the changing and functioning of any local congregation can be established in more than one way. For example, it could be described by way of listening to stories about and in the congregation. In essence it deals with what Osmer describes as 'priestly listening' within the 'descriptive empirical task' (Osmer 2008:28).

The process of listening embraces different approaches, from informal to formal and structured; all approaches have value and contribute to the understanding of the congregation. There is, and remains, space for statistical analysis of facts, data and interpretative information in and from the congregation. The guidelines stay the same whichever way 'listening' is being employed. The congregation is a contextual reality and in this sense a sociological reality, but as a religious congregation it is more than a sociological reality. Theological points of departure, specifically a practical theological ecclesiology, cannot be ignored as directional coordinates. One of the definitive questions is how the congregation takes part it this own analysis, thus becoming part of the theological reflection. A congregation is not analysed in the manner that a doctor diagnoses a patient. The consultant or task team accompanies the analysis of a religious congregation by itself. In the wider methodology of congregational analysis these congregational processes are of critical importance. It is connected with a confessional acknowledgement that the religious congregation also functions spiritually independently (Firet 1977:236). Congregational analysis can be described as 'returning the ministry to the people' (cf. Ogden 1990).

1.4 A further leading principle in the establishment of values for an empirical analysis is of an ecclesiastic nature. What is the congregation supposed to be involved in, in whichever context: this on the normative level (Osmer 2008:129-173). With what and where is God busy in his world? With what are his supporters as a religious congregation busy? If it is accepted that the congregation has been formed to give expression to God's purpose for humans, what then is the agenda? In practical theology it is generally accepted that this 'business' of the Church, and specifically the congregation, is the coming and seeking of the kingdom. It is not possible to escape this field of tension. If this is not professed the Church is reduced to another sociological organisation and the congregation is judged only against its congregational value. This is the field of tension between obedience to its calling (understood from a theological perspective) and the social values of the congregation. The field of tension has to remain. The realities of the kingdom keep it on the table of the congregation. It is, and should be part of the tension created by a missional ecclesiology. What is conveyed in this paragraph is not the discontinuation of tension, but the emphasis that the normative within confessional churches co-determines. The exegesis of the Bible texts is as important as the exegesis of the context. They are, however, not equally authoritative. As difficult as it may be to identify these 'normative values' it is necessary. In a congregational analysis the following must be taken account of:

- The missional being of the congregation.

- The critical role of service as a congregational fulfilment of a role in the arrival of God in the congregation and through the congregation to this world (Nel 2009).

This last requirement determines and informs the necessity and content of the congregational analysis as part of its theological and empirical identity. 'Discerning the local congregation as a defined and as an empirical subject plays a major role in answering the research question. The hypothesis is that when theology is taken serious local congregations can be analysed, but it is driven by specific theologically informed motives' (Nel 2009). The faithfulness of the congregation to the Gospel and the missional integrity of it as a local faith community can therefore, as an empirical reality, be analysed. The next question is then to describe this empirical process of analysis.

2. CONGREGATIONAL ANALYSIS FROM AN EMPIRICAL STANDPOINT

Therefore the next question is: what contribution can an empirical methodology deliver in the process of congregational analysis? As already referred to, this brings into play Osmer's (2008:28) first question, namely: What is happening here? In the first instance it can be argued that the methodology of a congregational analysis should be regarded as a process.

Congregational analysis is part of a greater process of development and growth within a congregation. It, therefore, cannot take place in isolation in a congregation. It should make a contribution to the process through which a congregation researches the purpose of its existence. Congregational analysis is in itself a process. By considering it as part of the methodological process, the standard of congregational analysis can be improved, making it part of an answerable process (Bruce & Woolever 2010:8). Attention will be paid to the following methodological aspects:

A congregational analysis as part of a research cycle.

A mixed methodology as a point of departure for congregational analysis.

A few methodological requirements for congregational analysis.

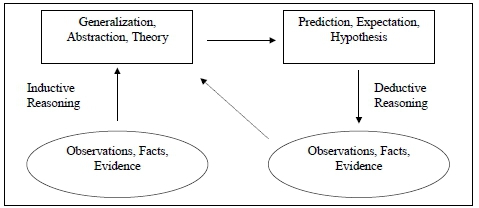

2.1 All empirical investigations take place within a specific research cycle and a congregational analysis could, therefore, also be located within such a cycle. The empirical research can commence at various points within the cycle: in some cases it starts as theories and generalisations concerning a specific matter, while in other cases it could start with certain observations. With whichever question or observation it commences, it should, for the sake of a responsible process be carried through the cycle at least once. Tashakkori and Teddlie (1998:25) present the following as a responsible empirical research cycle:

Due to the contextual nature of congregations it can be assumed that in most of the cases an inductive deliberation would be used (Hendriks 2004:212). Inductively a problem can be observed within a congregation. The manner of care of the different age groups can lead to the question whether everybody in the congregation is looked after inclusively? The differences in age groups or generations could be investigated and then defined or interpreted in terms of a theory or a generalisation. On a deductive level it can be assumed that the postmodern human being cares less for his fellow creature, living more in an own and private world. An investigation within a specific group can be carried out to establish whether people with a post-modern view of life and the world are more individualistic, and are, therefore, less disposed to care for his/her fellow creature. In the case of a congregational analysis space should be left for both an inductive and deductive approach.

2.2 A mixed methodology can serve as a point of departure for congregational analysis. 'Mixed methods research is defined as a procedure for collecting, analysing and "mixing" both quantitative and qualitative data at some stage of the research process within a single study to understand a research problem more completely' (Ivankova, Creswell & Plano 2009:261). 'A mixed methodology is more than just collecting data from a quantitative or qualitative strand but involves the connection, integration and linking of these two strands' (Creswell 2010:51). The empirical research process and the nature of congregations make it essential that both a qualitative and quantitative approach should be used at certain stages. A 'mixed method' creates the opportunity to obtain a more comprehensive picture. On the contrary, in the process of congregational analysis it is essential to create space for a qualitative and quantitative approach and even possibly for a narrative one (see Meylahn 2012:56-63).

Quantitative research emphasises the quantification of information, and behaviour is described in terms of certain variables (Babbie & Mouton 2001:49). Qualitative research has as point of departure "... the insider perspective on social action" (Babbie & Mouton 2001:53). The purpose of qualitative research is to describe and understand, instead of explaining and predicting. The question is whether a choice could be made between qualitative and quantitative research? Quantitative research is embedded between a positivistic and empirical approach, and qualitative research between a constructionist and phenomenological orientation. The two approaches stood opposed to each other for a long time (Tashakkori & Teddlie 1998:3). A more pragmatic approach developed over time: '...[T]he use of whatever philosophical and/or methodological approach works for the particular research problem under study' (Tashakkori & Teddlie 1998:5). This means that the methodological tools, which 'work' in terms of the research question or empirical investigation, are used (Tashakori & Teddlie 1998:21). Space should, therefore, be allowed for quantative as well as qualitative research (cf. Ivankova et al. 2009). A mixed methodology will certainly add value to the process of congregational analysis because of the complexity of congregational life.

2.3 Certain methodological requirements for congregational analysis can be mentioned. The methodological dimension of a congregational analysis, in particular on a formal and structured level, requires that certain guidelines should be followed. In this regard the basic requirements are reliability, validity and representivity.

Reliability, as a quality of measurement, means that a specific technique, if repeatedly applied to the same object, should produce a similar result each time (Babbie & Mouton 2001:119, Babbie 2011:129). Neuman (2001:164) describes reliability as '.dependability or consistency. It suggests that the same thing is repeated or recurs under the identical or similar conditions.' The central requirement for validity in the process of data collection is reliability, that is, whether the application of a (valid) measuring instrument on various research groups under different circumstances will lead to the same observations (Mouton & Marais 1993:81). Four variables determine the reliability of the observations: the researcher(s), the subject being studied, the measuring instrument and the context of the research (the circumstances under which the research is taking place). Attention must be paid to each of these variables during the course of an empirical congregational analysis.

The requirement for reliability is applicable to both quantitative and qualitative investigations. Reliability refers specifically to consistency in qualitative research (Neuman 2001:170). Reliable interviews can be assured through pre-testing of interview schedules, the training of interviewers, selected structured choices , cross-testing of answers, and open questions (Silverman 2001:229).

The interpretation and conclusions made on the basis of the analysis must also be reliable. Mouton and Marais (1993:106) point to two aspects which would yield reliable conclusions:

- Are the facts (the data) obtained reliable?

- If it is assumed that the evidence is reliable, does it present adequate support for the conclusion?

Congregational analysis, whether quantitative or qualitative, cannot be carried out without reliability.

Validity refers to the extent to which the measuring instrument reflects the real meaning of the concept (Babbie & Mouton 2001:122, Babbie 2011:131-134). "Validity suggests truthfulness and refers to the match between a construct, or the way a researcher conceptualizes the idea in a conceptual definition, and a measure" (Neuman 2001:164). Silverman (2001:232) describes validity as truth "... interpreted as the extent to which an account accurately represents the social phenomena to which it refers." Reliability is required for validity. Reliability is, however, more easily obtainable than validity. As is the case with reliability, the requirement with regard to validity for both quantative and qualitative research applies. In qualitative research validity specifically refers to "... authenticity ... giving a fair, honest, and balanced account of social life from the viewpoint of someone who lives it everyday." (Neuman 2001:171).

It is furthermore necessary to distinguish between internal and external validity (Mouton & Marais 1993:50-51):

- Internal validity refers to the fact that a specific study has generated accurate and true findings regarding the relative phenomenon being studied. The question that has to be answered is whether the deductions are valid regarding the happenings in the congregation

- External validity, which is a further step, refers to the fact that findings of a specific project are representative of other similar cases. The findings, therefore, have a wider validity than only the project. External validity and representivity are, therefore, synonymous.

Mouton and Marais (1993:41-42) point to the following threats to validity in research:

- The ecological fallacy of coming to specific conclusions regarding groups when only individuals were studied, or vice versa. In the case of a congregational analysis this would, for instance, mean that the view of a few individuals would not be valid for the whole congregation.

- The reductionistic tendency refers to the tendency amongst researchers to provide in their own research only explanations in terms of their own disciplines. In this manner social explanations for a phenomenon are, for instance, presented without taking economic factors in consideration. A holistic approach would work against this tendency. It goes without saying that in the case of a congregational analysis the use of various disciplines would provide a more holistic and comprehensive explanation to a congregation.

Silverman (2001:232) refers to two ways of ensuring the validity of qualitative research:

- Different data bases (quantitative and qualitative) can be compared through the use of different methods (observation, interviews, and so forth) to establish whether the same conclusion has been arrived at; this is known as triangulation.

- The researcher can take his findings back to the subject studied. If they agree with the findings, the validity is stronger. This is known as respondent validity (Silverman 2001:233).

It could sometimes happen that the richness of a concept be diminished by a reliable and valid description of the concept. This is an inevitable problem, but could be overcome by using several different measures, taping the different aspects of the concept' (Babbie & Mouton 2001:233). As with reliability, validity is also an important concept which should be considered in a congregational analysis.

The question regarding representivity is who should during the congregational analysis be included or excluded. In this regard sampling is important. 'Sampling is the process of selecting observations' (Babbie & Mouton 2001:164). Sampling is particularly emphasised in quantitative research. The purpose is to carry out representative sampling in order that generalisations regarding the greater group can be made. Quantitative research makes use of random sampling. An important principle of random sampling is that it should be representative of a specific population or group. This happens when each member of the population has an equal opportunity to become part of the sampling exercise (Babbie & Mouton 2001:173)

Qualitative sampling does not emphasise the nature of representation to that extent. The purpose of sampling in this case is '. to collect specific cases, events, or actions that can clarify and deepen understanding' (Neuman 2001:196). In qualitative research use is made of non-probable or non-random sampling. . Examples of non-randomized samples are accidental, quota, purposeful and snowball samples (Neuman 2001:196). In this case the limitations should be indicated clearly.

Representivity is an important methodological requirement for congregational analysis as an empirical project. The critical question is who is being listened to and what weight is accorded to the voices. Do the leaders of a certain group always know best? Is there not at times too much weight given to ministers during the process of analysis? The requirement of representivity creates a framework within which the different voices can be listened to in a credible manner.

3. CONGREGATIONAL ANALYSIS: GUIDELINES FOR A SOUTH AFRICAN CONTEXT

In this section empirical congregational analysis within and for a South African context is looked at. What should an empirical investigation look like which would help in a South African congregation, taking the South African context seriously? The concept of 'contextualisation' can be of assistance, because it deals with the message of the Church which incarnates '. itself in the life and world of those who embraced it' (Bosch 1991:420-432). The discussion regarding congregational analysis poses at least two questions:

- How is the context within the process of congregational analysis established?

- How does the South African context affects the congregational analysis which should be undertaken?

3.1. The context of the congregation

Firstly, how is the context established within the process of congregational analysis? The congregation is not only a theoretical possibility, but also an empirical reality. Nel (1994:12) correctly distinguishes between the congregation as a defined subject and as an empirical one (see point 1 for a discussion of this). Seen from a theological and theoretical perspective, it is clear that the congregation finds itself in a specific form within a certain locality, which constitutes the context of the congregation. To ensure that a congregation does not stagnate and be caught up in maintenance, a congregational analysis as part of a greater process of growth and development of the congregation is imperative. 'Contextual analysis is necessary when a congregation is self-centred, or to such an extent focused on its own institutional well-being that it loses sight of its missional character and the needs and challenges that must be addressed in its community' (Hendriks 2004:69). Stagnation of a congregation can easily takes place, if caught up only in satisfying its own requirements, ignoring daily needs. The context and changes in this regard cannot be ignored.

The interaction with the congregational context is of critical importance. Which factors can further the interaction between the congregation and its context? From an investigation of '. de christelijke presentie in een (grote stads)wijk' ("a Christian presence in the city suburbs") which Schippers and Jonkers (1989:31-53) carried out in four cities in the Netherlands (Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam and Jonkers) the following factors are mentioned to improve the interaction between congregation and context:

- Openness. There is an open attitude from the congregation towards the community. There can be no question of a closed Church attitude looking only inwards. This means that an ecumenical attitude should prevail, as well as an attitude of service to the 'others' in the congregation.

- Interaction. The community is continuously changing and mobility within it is substantial. This results in tension and anxiety within congregations. The congregation cannot be kept imprisoned by the attitudes of the middle class. The process of learning leads to an acceptability to learn from others and this normally takes place within a network of relations.

- Development of identity. An openness towards, and an interchange with the community inevitably leads to change or development in the identity of a congregation. The other and the poor in the community are in interaction with the congregation and expect that the congregation responds to them. This challenges the congregational identity and can lead to change or development in the congregational identity.

Openness, interaction and the development of identity are three concepts which determine and describe the interaction between congregation and context. How can this be addressed in a congregational analysis?

'Congregational studies' (see Carroll 1990; Ammerman et al. 1998; Hendriks 2004) as a methodology for congregational analysis pays specific attention to the interaction as a field of research between the congregation and the community. 'Congregational studies' emphasises that an important part of congregational analysis is to ascertain the social context within which a congregation is placed. Social context refers to the local and global world within which the congregation exist.

The term used by both Ammerman et al. and Hendriks is the 'ecological framework' of the congregation, with it as an organism within a specific environment. The social and religious worlds are formed by various 'organisms'. The congregation is an 'open system' which functions within a specific context and for that reason there is interaction between the congregation and the social environment. The latter consists of the residential or geographical area within which the congregation is situated, and the economic and political entities which influence it: even globalisation influences a congregation (Ammerman et al. 1998:41)

The interaction between the congregation and the surroundings takes place on various levels demographically: the composition of the population, a shared culture and organisations which function in an interactive manner with the congregation. A wide variety of individuals, cultures and organisations shapes the context of each congregation. 'By carefully studying this context and discovering a place within it, congregations can work together for good' (Ammerman et al. 1998:74).

Hendriks (2004:76-79) points to three levels which should be taken in consideration in terms of congregational context:

1. The greater world viewed on a macro level. The congregation is part of a global environment webbed together in networks, technological innovations and sosio-political changes. Friedman points to the fact that the world has become flat: "I am convinced that the flattening of the world, if it continues, will be seen in time as one of those fundamental shifts or inflection points, like Gutenberg's invention of the printing press like the rise of the nation-state, or the Industrial Revolution ." (2006:49). Congregations in South Africa are inseparable from other parts of Africa and are, therefore, part of the continent's challenges and problems. Within the South African context congregations are part of a post-apartheid and democratic society which presents different questions to congregations.

2. The meso level refers to the district and greater community where a congregation is situated. The influence of the province, city or rural area of which the congregation is part of, cannot be ignored. The local community's distress and needs like poverty, unemployment and xenophobia also pose challenges to the congregation.

3. Finally, the micro level refers to the congregation's immediate surroundings. The people and suburb where the congregation is situated form the immediate context and should be reflected in the congregation.

As already mentioned a congregation should understand its calling and reason for existence, and live accordingly. All three abovementioned levels describe the context of the congregational ecology. A congregation which deals with this in a serious manner should, therefore, give attention to all three levels in its search and evaluation of a contextual congregational service.

3.2 The influence of the South African context on congregational analysis

The importance and place of the context within the process of congregational analysis has been discussed above. The next question is how the South African context has an impact on the process of congregational analysis? Without being exhaustive the following markers which cannot be ignored are mentioned.

If the three levels of ecological analysis are considered the following question can be asked: from where can the information regarding the context and situation within the three levels be obtained? An important point of departure is to understand that it is more than a theological question. Different disciplines will have to be involved. Different theological perspectives help to inform the discernment process (Van Gelder 2007:105). Therefore, it is a multi-disciplinary project. Without being exhaustive it can be pointed out that it has, amongst others, an economic, political, educational and sociological dimension. Congregational analysis is, therefore, an activity which heeds the voice of various disciplines. By doing this the danger of reductionism as a threat is avoided.

A single congregation can only contribute to a limited extent within the community. The matter rather concerns all the congregations within a community who can together play a comprehensive role and make a contribution. It calls, therefore, for an ecumenical dimension for the involvement of a congregation in a specific community. The history of being divided within the South African context requires that congregations which were 'far' away from each other will become closer and work together for the kingdom and the community, thereby creating a space wherein various voices will be listened to.

How can a congregation listen to the voice of a wider community and the matters which society wants to deal with? The demography of a country and/or region is always an important voice; StatsSA provide in this regard a useful service (see for example the General Household Survey, GHS 2013). The South African reconciliation barometer of the Institute of Justice and Reconciliation provides data and information regarding reconciliation in the country (see Cilliers & Nell 2011). It is also possible, within the South African context to look at the following three voices as examples to engage with the South African context:

- From within the ecumenical religious environment the conference in 2003 of the South African Leadership Assembly (SACLA) placed the following seven major issues on the table: HIV/Aids, violence, racism, poverty and unemployment, sexism, family crises and violence, and corruption (Cilliers 2007:2-4). The argument could be that congregations and denominations in their environment cannot ignore these major problems, if they want seriously to consider the South African context.

- A second voice in the field of scenario planning is the Dinokeng scenario of 2009. Dinokeng identified important liabilities for the South African society that are poverty, unemployment, education and within the field of health care the impact of HIV/Aids and TB. Life expectancy has decreased from 63 years in 1990 to 51 in 2006. Religious organisations were once voices of poor people, however, since 1994, with a few notable exceptions, they have lapsed into their comfort zones and are preoccupied exclusively with the after-life (Dinokeng n.d.:18). The remark on the role of religious organisations in the South African society is significant and should be a challenge to congregations. The Dinokeng scenario team chooses for a walk together, and not a walk apart or walk behind, strategy (Dinokeng n.d.:68-69). The challenge is for churches and congregations, to be engaged and taking responsibility for the challenges that society are facing. The question is which role congregations can play to make the third scenario -'walking together' - a reality?

- The National Development Plan (NDP) is a third voice that could be used as an instrument to identify challenges in the South African society. The NDP remarks that the continued social and economic exclusion of millions of South Africans, reflected in high levels of poverty and inequality, is the biggest challenge (NDP 2012:7). Eliminating poverty and reducing inequality is there for key strategic objectives (NDP 2012:29). The NDP states that for many South Africans, faith is an important element of social capital, and religious institutions are also useful for the social cohesion project because they are a repository of social values (NDP 2012:27). Congregations could position themselves by using social capital (or spiritual capital) to build social cohesion and strengthen social values in the South African society.

Contextualising is not a comfortable or simple matter. Only a few markers have been indicated above in the search of a process of congregational analysis which seriously engages the South African context.

4. A CRITICAL REFLECTION REGARDING THE ROAD AHEAD

It is, in light of the preceding arguments, of critical importance in a congregational analysis that three aspects are kept in mind:

- Theologically a congregation is more than and different from a social institution which should be governed and organised well: it concerns a practical theological ecclesiology which defines and describes a congregation. Congregations are instruments for the coming of the kingdom and an analysis should demonstrate the defects and possibilities for growth.

- Methodologically certain rules of play apply to be able to present a credible picture regarding the state of the congregation: and part of such an empirical process is to ensure that the analysis is reliable and valid. Only then can valid conclusions and generalisations made regarding a congregation and denominations.

- Contextually: congregations do not exist and function in a vacuum. Therefore, the locality and context of the congregation is important. Spaces should be created so that voices from the community and society can be heard, and as a result used for the development of a local congregational theology.

The SACLA giants, Dinokeng scenario and the NDP accord a critical place and role to congregations in the South African community. On the way forward and in the coming of the kingdom an empirical congregational analysis can assist congregations in making a difference within the framework of a contemporary ecclesiology.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ammerman, N. Carroll, J.W., Dudley, C.S. & McKinney, W. (eds.) 1998. Studying congregations. A new handbook. Nashville: Abingdon press. [ Links ]

Babbie, E. 2011. Introduction to social research. Canada: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

Babbie, E. & Mouton, J., 2001. The practise of social research South Africa, Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J., 1991. Transforming mission. Paradigm shifts in the theology of mission, New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Bruce, D. & Woolever, C. 2010. A field guide to Presbyterian congregations, Kentucky: John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Carroll, J.W. (eds), 1990. Handbook for congregational studies. Nashville:Abingdon Press. 6th print. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J. 2007. Creating space within the dynamics of interculturality : The impact of religious and cultural transformations in post-apartheid South Africa. IAPT April:1-24. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J. & Nell, I. 2011. "Within the enclave" - Profiling South African social and religious developments since 1994. Verbum et Ecclesia 32(1):1-7. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2010. Mapping the developing landscape of mixed methods research. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie, (eds.) Sage handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioural research, (California: Sage Publications), pp. 45-68. [ Links ]

Dinokeng 2009. Dinokeng scenarios: 3 futures for South Africa. [ Links ] [online] Retrieved from: http://www.dinokengscenarios.co.za/pdfs/book_small.pdf

Firet, J. 1977. Het agogisch moment in het pastoraal optreden. Kampen:Kok. [ Links ]

General Household Survey 2013. 2014. General household Survey 2013. Pretoria: StatsSA. [ Links ]

Friedman T.L. 2006. The world is flat. Penguin Books London [ Links ]

Hendriks, H.J. 2004. Studying congregations in Africa. Wellington: Lux Verbi.BM. [ Links ]

Ivankova, N.I., Creswell, J.W. & Plano, C.V.L., 2009. Foundations and approaches to mixed methods research. In K. Maree, (ed.) First steps in research, (Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers), pp. 253-282. [ Links ]

Meylahn, J-A. 2012. Church emerging from the cracks. A church in, but not of the world. Stellenbosch: SunPress. [ Links ]

Mouton, J. & Marais, H.C. 1993. Basic concepts in the methodology of the social sciences., Pretoria: HSRC, third impression. [ Links ]

National Development Plan 2012. "National Development Plan 2030. Our Future-make it work" [online] Retrieved from: Links ]poa.gov.za/news/Documents/NPC%20National%20Development%20Plan%20Vision%202030%20-lo-res.pdf" target="_blank">http://www.poa.gov.za/news/Documents/NPC%20National%20Development%20Plan%20Vision%202030%20-lo-res.pdf

Nel, M. 1994. Gemeentebou. Halfweghuis: Orion [ Links ]

_______. 1998. Gemeentebou:'n Reformatoriese Bediening. PTSA, 13/2: 26-37. [ Links ]

_______. 2009. Congregational analysis: A theological and ministerial approach. HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 65(1):432-448. [ Links ]

_______. 2011. Missionale integriteit en kontekstuele relevansie. HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 67(3):1-9. [ Links ]

_______. 2015. Identity-driven churches. Who are we, and where are we going?, Wellington: Biblecor. [ Links ]

Neuman, W.L. 2001. Social research methods. Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

Ogden, G. 1990. The new reformation. Returning the ministry to the people of God. Zondervan: Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Osmer, R.R. 2008. Practical Theology. An introduction. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. [ Links ]

Schippers, K.A. & Jonkers, J.B.G. 1989. Kerk en buurt. Kok, Kampen. [ Links ]

Silverman, D. 2001. Interpreting qualitative data. London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Tashakkori, A. & Teddlie, C. 1998. Mixed Methodology: Combining Qualitative and Quantitive Approaches (Applied Social Reseach Methods), California: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Van Gelder, C. 2007. The ministry of the missional church. A community led by the Spirit BakerBooks, ed., Grand Rapids, Michigan. [ Links ]

1 Part of this article was delivered by the authors as a paper ("Empirical and contextual congegrational analysis - meeting social and divine desires") at the IAPT conference at the Vrije Universiteit university in Amsterdam on 21-26 July 2011.