Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Theologica

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.35 supl.21 Bloemfontein 2015

Speech act reading of John 9 - Chapter 4

Ito Hisa

1. INTRODUCTION

Chapter 9 of John's Gospel, which belongs to the book of signs, is placed within the broader co-text where the controversy between Jesus and those who opposed him, especially the Jewish leaders, gradually became more intense. The polemic started at the Feast of Tabernacles in Chapter 7, and continues between Jesus and his opponents in Chapter 8. In 8:12, Jesus said, 'I am the light of the world' and referred to the theme of light and darkness. The miracle portrayed in Chapter 9 is a perfect example of this statement. Furthermore, additional inquiries about the ongoing issues of his origin and identity are made in this chapter.

In Chapter 10, the same issues are discussed in a different manner. For instance, not only does 10:21 explicitly refer back to the miracle event, but also the relationships between Jesus, the blind man, and the Jewish authorities are and depicted in the figures of speech. While the thieves and hirelings destroy the sheep, the good shepherd protects and gives life to his own sheep. Being an independent and complete story in itself, Chapter 9, still fits well into the present co-text.1

The author of this Gospel does not intend to furnish the exact date and location of this miracle story. Although this information seems to be of little importance to him in this instance, one can nevertheless assume this from the co-text. The date was sometime between late September/ early October and late December, as can be inferred from the references to the Feast of Tabernacles in 7:2 and to the Dedication Festival in 10:22. The location was somewhere in Jerusalem, as can be inferred from the fact that Jesus left the temple in 8:59 and, from the narration, that he was walking after that in 9:1. Some critics assume that it is the temple area (Schnackenburg [1968] 1980:240; Jones 1997:165).

2. OVERALL STRUCTURE

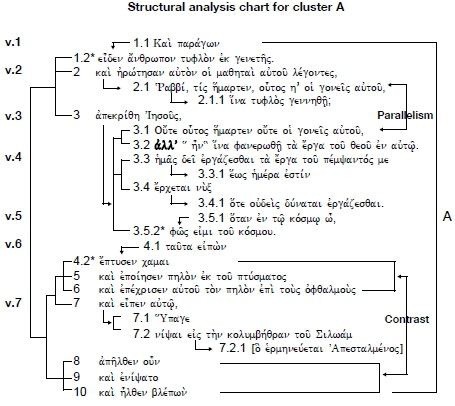

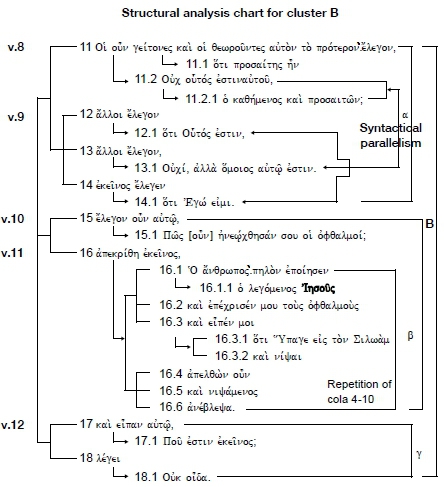

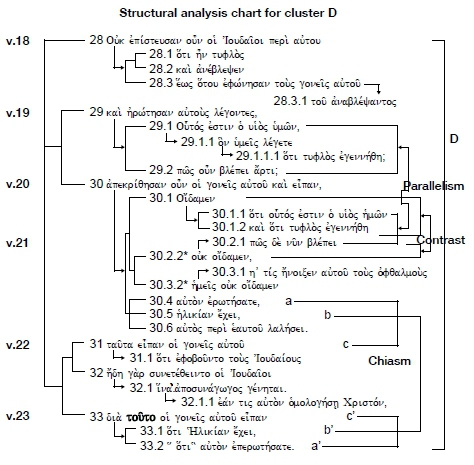

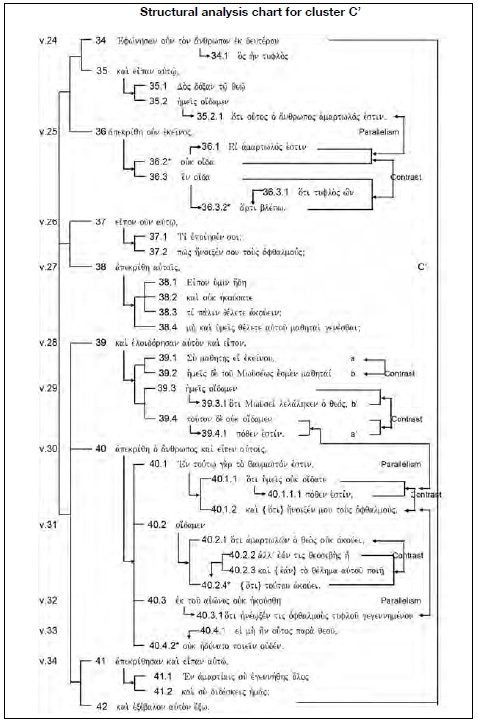

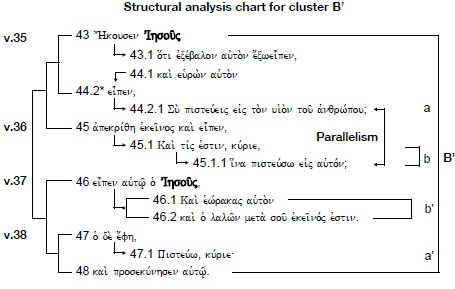

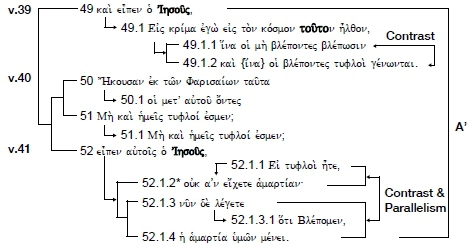

The forty-one verses of Chapter 9 can be divided into 52 cola. These cola can be separated to form seven different clusters based on their semantic contents.2 More significant is that these seven clusters can be viewed as a chiastic arrangement: 9:1-7; 9:8-12; 9:13-17; 9:18-23; 9:24-34; 9:35-38 and 9:39-41.3 This rhetorical feature itself reveals the author of this Gospel as an extraordinary literary artist (cf. Haenchen 1984:41-42). As a matter of fact, this chiasm is based on the seven dialogues between the characters, and each dialogue presents very intriguing and vivid interactions between the two (groups of) participants.4 This fact is probably one of the reasons why this Chapter as a whole has such a dramatic effect on the reader.5Because of the chiasm, the seven clusters can be referred to as cluster A, B, C, D, C', B', and A', respectively (cf. my structural analysis chart in Appendix 4).

3. CLUSTER A: THE DIALOGUE BETWEEN JESUS AND THE DISCIPLES (9:1-7)

3.1 Specific mutual contextual beliefs

3.1.1 Blindness and sin

The particular interest in the story of the blind man addresses the issue in terms of blindness and sin. In this instance, I wish to discuss this issue from the perspective of the relationship between human suffering and sin.6There is no doubt that the characters (Jesus, his disciples and the Jewish authorities) in the narrative of John 9 share the common understanding regarding the connections between sin and suffering held by Jewish people in those days. Blomberg (1992:301) comments on Jesus' utterance to the man healed at the pool of Bethesda in 5:14: "Jesus presumes the common Jewish view that illness was a punishment for sin". When Buttrick (1979:338) gives his exposition on the account of the healed leper in Matthew 8:1-4, he states: "The rabbis usually regarded it [leprosy] as a direct punishment for various sins." Quast (1991:72) points out the background: when "a child was born with a sickness, the traditional retributive link between sin and suffering was challenged". This traditional link can be traced back to Old Testament passages such as Exodus 20:5 (also Nm 14:18; Dt 5:9; Is 65:7; Jr 32:18), which indicates that the fathers' sins were the cause of the punishment of the children; Job 4:7-8 where the retribution based on cause and effect is suggested, and Genesis 25:22 with Psalm 58:3 which helps to build the implication that sin could be induced by the babies even in their mothers' wombs (Brown 1966:371; Ps 51:5). Barrett (1955:295) further refers to the case that "when a pregnant woman worships in a heathen temple the foetus also commits idolatry". Edersheim's ([1967] 1976:163) remark reinforces Quast's point and mentions that "children benefited or suffered according to the spiritual state of their parents was a doctrine current among the Jews ... And sickness was regarded as alike the punishment for sin and its atonement". Schnackenburg ([1968] 1980:496) comments on the possibility that "malformations and physical illnesses present from early childhood were explained and used as the basis for admonitions to a pure married life". On the other hand, I wish to point out that there was a counterargument against this commonly held view: "From as far back as the time of Jeremiah and Ezekiel there was opposition in Israel to the idea that children have to pay for the sins of their parents" (Schnackenburg [1968] 1980:241; cf. Jr 29-30; Ezk 18:1-4, 19-20). Furthermore, the vast majority of expositors agree that the gnostic doctrine of the pre-existence of the soul was not under consideration in the exchange between Jesus and his disciples in 9:2-3.7

I can conclude that the view in question was common in the days of both the characters and the author. This means that the reader is also aware of this link between human suffering and sin.

3.1.2 Miracles

The subject of miracles has undoubtedly provoked one of the most heated discussions in New Testament studies. In such discussions, scholars often express their concern about the danger of viewing the miraculous events in the first century CE from our modern point of view (Vorster 1986:49; Pilch 1992:30; cf. Elliott 1993:11). Drawing attention to a distinction between miracles and miracle stories, Vorster (1986:48) stresses that "the miracle traditions in the New Testament were meant to serve as propaganda for faith in Jesus and in Christianity" (cf. Theissen 1983:259). Following this view, I shall discuss, in this section, the way in which the author presents miracles as signs in comparison with the synoptic presentation of miracle accounts. In addition, I shall refer to the knowledge of the reader and the characters concerning Jesus' miracles and the author's use of some finer details (e.g., spittle).

At the outset, I shall introduce the definitions of miracles and miracle stories. "In biblical scholarship the English word miracle normally denotes a supernatural event, that is, an event which so transcends ordinary happenings that it is viewed as a direct result of supernatural power" [Blackburn's italics] (Blackburn 1992:549). On the other hand, "miracle stories denote[s] relatively self-contained narratives in which an individual miraculous happening constitutes the, or at least a, major focus of the account" [Blackburn's italics] (Blackburn 1992:549). In the realm of Johannine miracles, Blackburn (Blackburn 1992:555) makes a good observation: "Jesus' miracles ... are set within the context of the one grand miracle, the incarnation of the Logos" (John 1:14). This observation is significant in two ways. It provides an overall framework for Johannine miracles and it suggests that the focus of Johannine miracles is Christological (Fortna 1970:228). Barrett (1955:63) echoes this: "The miracles once grasped in their true meaning lead at once to the Christology, since they are a manifestation of the glory of Christ (2:11)" (cf. also Nicol 1972:119-122). The difference in their emphasis on the Christological aspect of miracle stories is recognised between John and the synoptists. In the Synoptic Gospels, his miracles are frequently designated as δυνάμεις, mighty works or deeds, which emphasise Jesus' extraordinary power and often point to the manifestation of the kingdom of God (Blackburn 1992:555-556; Culpepper 1998:21). According to Theissen (1983:280), "The combination of eschatology and miracle in Jesus' activity is distinctive ... Jesus sees his own miracles as events leading to something unprecedented. They anticipate a new world". By contrast, John records only a few selected miracles (cf. John 20:30; Fortna 1970:100-101) and repeatedly describes these as σημαία signs. The signs are used to point primarily to Jesus' identity as the Christ, the son of God, and have the specific function to evoke faith in him (Blackburn 1992:556; Salier 2004:117-119). They demonstrate markedly "the character and power of God, and partial but effective realizations of his salvation" (Barrett 1955:64). John also refers to Jesus' miracles as his works (cf. Nicol 1972:116). "As such, they are also the works of God himself; there is a complete continuity between the activity of Jesus and the activity of the Father (cf., e.g., 5.36; 9.3; 10.32, 37f.; 14:10)" (Barrett 1955:63; Carroll 1995:135). In addition, I consider it important to clarify a further difference in terms of the effect of Jesus' miracles. Since we can consider Johannine miracles themselves to be eschatological events (Barrett 1955:64), the significance of the miracles is not hidden from those who encounter the miracles. Therefore Johannine miracles demand a response from the witnesses, either to believe or not at the time when the miracles are performed (e.g., John 2:11; 4:53; 5:16; 6:14; 9:16, 18, 38; 11:45). Conversely, as Barrett (1955:64) points out, in the synoptic miracles "the eschatological significance of the ministry of Jesus is a hidden thing, which will be understood only in the eschatological future; thus the signs (in the sense of miracles) are for the present secret signs. Even the disciples fail to understand them (Mk 8:17, 18, 21)".

Some details of Jesus' miracle

Regarding some details of Jesus' miracle of giving sight to the blind man, I wish to highlight three items, namely spittle, mud or clay, and the act of anointing, because this miracle, among all the miracles Jesus performed in the Gospel, seems to be the only incident where Jesus performed some particular actions during the miracle. The question then follows: Is there any significance in the author's depiction of these items?

"In antiquity spittle was believed to be of medical value" (Barrett 1955:296; Salier 2004:116). Theissen (1983:63) maintains that spittle appeared in the healing stories of blindness (Mk 8:22-26; John 9:1-7), because it was deemed as a remedy for eye disease. In his report, healing substances such as spittle "were rubbed into the eyes of the blind and those with eye-diseases" (Theissen 1983:63). However, spittle was not only used for such treatments. Theissen (1983:93-94) states that "spittle can also be used in exorcisms, though there it seems to belong more to the 'gesture of spitting as a sign of contempt', which continues to have an aggressive significance in our own day". This spitting gesture may have some significance in the story of John 9 concerning the ancient game of challenge and response (cf. section 4.1.2 in Chapter 3 and the analysis on 'CS' in 9:6). In addition, strictly speaking, Jesus did not use his spittle alone in the healing. He used it to make mud, "a healing paste out of spittle and earth" (Theissen 1983:94). This is interesting when comparing this Johannine miracle with Mark's miracle story (8:22-26), where Jesus gave sight to a blind man only by anointing his spittle on his eyes. In that instance, Jesus did not need to make mud. But the author particularly mentions mud. As will be noticed, the author's reference to making mud plays a crucial role in the plot of his story. The mixing of mud would constitute a double violation of the Sabbath laws in conjunction with Jesus' healing itself on the Sabbath.8 Furthermore, it was common that some kind of healing touch was involved in many miracles,9 and the laying on of hands was a usual form (e.g., Mk 5:23; 7:32; 8:23-25; Ac 28:8). It is obvious that the Johannine Jesus in 9:6 also touched the eyes of the man born blind. We can consider this action to be the laying on of his hands, as in the case of Mark 8:23-25. The main reason for touching is that "the touch transfers miraculous vital power to the sick person" (Theissen 1983:62). The healing touch also assures the recipient that the healer is doing something for his benefit. In the story of John 9, Jesus' touching or anointing, with his command to wash in the water of Siloam, should be regarded as the proof that the miracle was ultimately performed through Jesus' power (Beasley-Murray 1987:156).

The knowledge of the reader and the characters

I shall now discuss Jesus' miracles from the reader's perspective. From his reading up to Chapter 9, the reader knows the miracles Jesus performed at Cana (2:1-12), at Capernaum (4:43-54), at Bethesda (5:1-18), on a mountain (6:1-15), and on the Sea of Galilee (6:16-21). In addition, the reader is assumed to know that these miracles are signs that point primarily to Jesus' identity as the Christ, the Son of God, and demand a response from the witnesses, including the reader himself. However, the reader has no knowledge of greater signs than those Jesus would still perform in Chapters 9 and 11.

How much do the characters know of Jesus' miracles? The characters who were present in cluster A are Jesus, his disciples and the blind man. There is no need to mention Jesus' knowledge about his miracles. The disciples witnessed the majority, if not all, of his miracles until Chapter 9: the text explicitly tells us that they were with Jesus when Jesus performed his miracles at the wedding (2:2, 11), on the mountain (6:3), and on the sea (6:16-21). At the two healing miracles (4:43-54; 5:1-18), the text does not clearly report their presence, but we can presume that they were with Jesus. This means that they were perhaps the best witnesses of his miracles and responded to them positively (e.g., 2:11). By contrast, the blind man did not witness Jesus' miracles at all, for he was blind and his meeting with Jesus in Chapter 9 appeared to be his first encounter with Jesus.

3.1.3 Siloam

In this section, I shall discuss possible beliefs regarding the term Siloam based mainly on Grigsby's (1985) essay. According to Grigsby, it is assumed that the characters and the reader are aware of the symbolic role of Siloam's waters. They would have regarded Siloam's waters as cultic (to be used for a ritual purification) as well as "living" (Grigsby 1985:228). Brown (1966:372) endorses Grigsby's view concerning the cultic aspect: "Mentioned in Isa viii 6, the water of Siloam was used in the water ceremonies and processions of Tabernacles. Rabbinic sources mention it as a place of purification". As for the living aspect, Grigsby (1985:228) suggests that the status of Shiloam's water "as 'living water' ... was especially prominent during the feast of Tabernacles, the backdrop for the John 9 episode". In addition, "the Rabbinic discussion about the 'sign of Siloam' ... that the free-flowing fountain of Siloam signifies God's blessing - especially in the Messianic age" would also have been known to them (Grigsby 1985:229). Based on these observations, he further examines the symbolism of Siloam in relation to the living water motif in the Gospel, introduced for the first time in the episode of the Samaritan woman. He suggests three significant aspects of this symbolism (Grigsby 1985:232-234): Siloam's waters symbolise Jesus' works to endow eternal life; to cleanse from sin, and to provide living water as the Messiah. The reader is, of course, aware of the close link between living water and the Spirit mentioned in 7:37-39 (Jones 1997:174). Lastly, I wish to point out how Siloam's waters relate to Jesus' miraculous healing of the blind man. Like the Rabbinic discussion earlier, the sign of Siloam is reflected in this miracle which signifies God's work as his blessing. In other words, Siloam's symbolism is realised in this magnificent miracle including its effects on the man born blind described in the entire chapter. Although the success of the miracle is attributed solely to Jesus' power, Siloam's waters play a substantial role in the meaning (significance) of the miracle.10

3.1.4 The 'I am' statements

The frequent occurrences of the Greek formula έγώ €ΐμι and the way in which it is used in the Fourth Gospel have made many scholars investigate its meaning in the text and its significance in Johannine theology.11Schnackenburg ([1968] 1980:79) demonstrates the remarkable comparison with its usage in the Synoptics. Any reader of John's Gospel is constantly reminded that Jesus' 'I am' sayings are significant expressions, which the author uses for an effective communication with the reader (Bernard 1928:cxxi). John 9 also contains such an expression in verse 5, although this instance is debatable as to whether this is a 'pure' formula or not (cf. the analysis on 'GA' in 9:5). However, this expression is the repetition of 8:12, which is a real occurrence of the Johannine 'I am' statements (cf. Tenny 1981:101), and the author most likely alludes to the εγώ ειμι complex of ideas in 9:5. Hence, the analysis of 9:5 also requires an examination of these sayings.12 The way in which the reader understands these sayings up to Chapter 9 greatly illuminates his comprehension of Jesus' expression in 9:5. To begin with, since the expression in 9:5 appears to belong to the 'I am' sayings with an image, I wish to point out the instances of these sayings (with the emphasis on the occurrences from Chapters 1 to 9):

a. The 'I am' sayings with an image (from Chapters 1 to 9): 6:35, 48, 51; 8:12; 9:5.

b. The 'I am' sayings with an image (from Chapters 10 to 21): 10:7, 9, 11; 11:25; 14:6; 15:1, 5.

Among the seven 'I am' sayings with an image in the Gospel, only two (the bread of life and the light) are recorded in the first nine chapters. One should note that Jesus uttered these two sayings in the context of his discussions with the 'Jews': in the discussion of the bread of life (6:22-71), and of the light of the world and Abraham's true children (8:12-59). These sayings appear to be a very important theme in these dialogues (Smalley 1978:90). More importantly, these sayings are closely linked to his signs (Du Rand 1994:94; Ball 1996:146). In order to understand their importance, I shall scrutinise an overall picture of the Johannine 'I am' statements, first, from the author's perspective.

The author's perspective

The εγώ ειμι sayings in the Fourth Gospel are employed in various ways as well as in different forms. Ball (1996:146) observes: "The great variety of settings in which the words έγώ ειμι are used by the Johannine Jesus show that it is a phrase which pervades the whole Gospel. It is restricted neither by audience nor by religious context." This diversity makes it difficult to categorise these sayings clearly.13 Nevertheless, I shall employ a more conventional categorisation in which Ball (1996:14) combines Brown's second and third categories in footnote below: the 'I am' sayings without an image (the absolute use) and the 'I am' sayings with an image (the predicate use).14 This categorisation may correspond well to the meaning of the formula in the Gospel. The meaning of the formula can be explained in various ways.

Generally speaking, "while the 'I am' sayings without an image point to formal parallels in the Old Testament to explain Jesus' identity, the 'I am' sayings with an image point to conceptual parallels to explain Jesus' role among humanity" (Ball 1996:260). This distinction is valid yet not rigid, because Jesus' identity may be dominant in the meaning of the absolute use, whereas his role may be in that of the same form, and vice versa (Ball 1996:260). Regardless of whether the emphasis falls on his identity or his role, the main purpose of the εγώ είμι sayings is thus to reveal to the reader who Jesus is and what he does in relation to his believers and the world (Schnackenburg [1968] 1980:89; cf. Coetzee 1986:173).15 The 'I am' sayings "have the particular advantage of making the saving character of Jesus' mission visible in impressive images and symbols. The different images are simply variations on the single theme, that Jesus has come so that human beings may have life, and have it in abundance" (Schnackenburg [1968] 1980:88; Smalley 1978:90).

I shall examine the meaning of the 'I am' sayings with an image in relation to Johannine symbolism. As mentioned earlier (section 5 in Chapter 3), Koester (1995:13) suggests the twofold structure of symbolism used in the Gospel: "The primary level of meaning concerns Christ; the secondary level concerns discipleship...The clearest examples are the 'I am' sayings of Jesus." This structure, too, matches the description of these sayings as being Christological and soteriological. The interface between discipleship and a soteriological aspect in this relationship is an abundant life, which Jesus gives to his followers (who will have such life by discipleship).16

After a detailed literary study of the usage of these sayings in the text of John, Ball (1996:146-160, especially 157-160) makes several concluding remarks. I shall refer to only those remarks that appear to be relevant to this section. Firstly, he avers that literary studies of the 'I am' sayings "confirm the conclusions of Schweizer about the essential unity of the Gospel" (Ball 1996:157), despite their divergent usage in the Gospel. Secondly, "this approach has confirmed Zimmermann's view that there is a closer interaction between the predicate and the unpredicated sayings than has been granted in studies which have created a strict separation based on form" (Ball 1996:158). Lastly, he asserts that these sayings contribute considerably to the characterisation of the Johannine Jesus. In his own words, "[t]hese literary studies have shown the dominance of Jesus as the main character of the Gospel" (Ball 1996:159, 255). His other important comment, not as a conclusion, but in terms of a methodological consideration, is that literary studies of the Johannine text will guide a critic to discern a correct background for further understanding these sayings (Ball 1996:160). This is important, because the critic ought to have legitimate criteria to delimit his research on the topic, namely on the possible background of the εγώ ειμι sayings in this instance.

Burge (1992:355) considers three areas for possible background, namely non-Jewish sources, the Old Testament and Palestinian Judaism. Hermetic literature (Deissmann 1927:134-142; Burge 1992:355), Mandaean writings (Schweizer 1939:46-82; Meeks 1965:487-491; Bultmann 1971:225-226, footnote 3) and Gnosticism (MacRae 1970) chiefly represent non-Jewish sources in this instance (cf. Bernard 1928:cxvi-cxxi; Barrett 1955:242-243). However, scholars such as Brown (1966:535-538), Schnackenburg ([1968] 1980:83-86) and Smith (1995:112) agree that Palestinian Judaism and the Old Testament, in particular, should be perceived as the correct background.17 More specifically, as for the absolute use of the formula, "two Old Testament backgrounds have been proposed, in each of which God identifies himself by saying 'I am' (Septuagint: ego eimi)" (Smith 1995:112). One is Exodus 3:14 (cf. Dt 32:39), and the other is the reiterated usage of Second Isaiah (41:4; 43:10, 13, 25; 46:4; 47:10; 48:12; 51:12; 52:6; cf. 46:9; 48:17).18 With regard to the predicate sayings in John, Brown (1966:535) avers that these sayings "are adaptations of OT symbolism (bread, light, shepherd, and vine are all used symbolically in describing the relations of God to Israel)". The reason why Brown says so lies in the fact that it is difficult to trace any specific Old Testament passages as the clear-cut background (Smith 1995:112; Schnackenburg [1968] 1980:8).19

Nevertheless, if one considers these Johannine metaphors as a development of the revelation formula, numerous possible comparisons can be suggested as in the following examples (Schnackenburg [1968] 1980:84): shield (Gn 15:1), healer (Ex 15:26), keeper (Is 27:3), the first and the last (Is 41:4; 44:6; 48:12), saviour (Is 43:11), shepherd (Ezk 34:12) and helper (Hs 13:4).

The reader's perspective

I wish to clarify Jesus' expression in 9:5, in conjunction with the pure Johannine saying in 8:12, from the reader's perspective. According to Culpepper (1983:219), "the reader has extensive knowledge of the Old Testament". This suggests that the reader is able to understand adequately the meaning of the light of the world when Jesus revealed himself as such.20That is to say, the reader may be able to understand Jesus described in the 'I am' sayings in Chapters 8 and 9 as "the bringer of revelation and salvation" (Schnackenburg [1968] 1980:85).

The characters' perspective

In 9:5, there are two (groups of) characters on stage: Jesus and his disciples. Since Jesus was the speaker, Jesus should have known the meaning and significance of this saying. As examined earlier (section 4.5 in Chapter 3), the characterisation of the disciples, in this instance, can basically follow their general description established up to Chapter 9. In light of their general description, the disciples appeared to have good knowledge of the Old Testament and Jewish thought.21 This suggests that the disciples were presumably able to sufficiently understand the meaning of the light of the world. Moreover, the dialogue scene (9:1-5) gives no indication to jeopardise this assumption.

Lastly, I should point out that, when the εγώ ειμι sayings are uttered, they embody a double nature of revelation and concealment, as is the case with parables and symbolism. More precisely, the sayings will either evoke faith in the revealer or provoke unbelief against him. John 8 demonstrates the latter response in the unbelieving Jews who judged Jesus as an ultimate blaspheming offender. Conversely, John 9 depicts the former response in the faith of the blind man who believed in Jesus and thus identified Jesus as the light of the world.

I have thus discussed the mutual contextual belief of the 'I am' statements. For the sake of analysis, one should note how much of these sayings the reader and characters correctly understand.

3.1.5 Relationships between the characters

At the end of each specific set of mutual contextual beliefs in the seven dialogues (clusters), I shall discuss the knowledge of the specific speech situations and of the relations between the two parties in the narrative. In addition, I shall present this discussion in such a way that this knowledge should be valid for both the author-reader level and the character level.

With respect to cluster A, one point should be made clear. As indicated in the analysis below, this dialogue structurally comprises two interactions between the characters. One is the interaction between Jesus and his disciples, and the other is between Jesus and the blind man.22 Therefore, I shall describe this knowledge separately for these two interactions, but I shall not do so in the other clusters.

a. The knowledge held for the specific conversation between Jesus and his disciples is as follows:

- The relationship between Jesus and his disciples was one of teacher-pupil or master-disciple. Thus Jesus was superior to them.

- Both parties (Jesus and the disciples) knew that the man was born blind.

- Both parties basically knew the one who sent Jesus.

- Both parties basically knew the concept of sin.

- It is assumed that the disciples knew Jesus' self-disclosure that he was the light of the world and his ensuing statement that anyone who follows him shall not walk in the darkness, but shall have the light of life in 8:12.

b. The knowledge held for the specific conversation between Jesus and

the blind man is as follows:

- In terms of social status, Jesus was superior to the blind man who was a beggar.

- Jesus and the blind man had no personal relationship prior to their encounter.

- Because of the healing, the relationship between Jesus and the blind man became one of healer-healed, similar to that between physician and patient. Thus Jesus was also personally superior to him.

3.2 Overview and structural analysis chart

I shall make some remarks concerning the overview of cluster A (cf. also the structural analysis chart in Appendix 4):

1. There is an inclusio in this section. Both cola 1 and 10 focus on the

man who is blind from birth. Secondly, I find a certain contrast in this inclusio in terms of the man's physical conditions, that is, both his inability and ability to see.

2. Blindness and sight are two major motifs in this cluster, most likely, in the entire chapter.23

3. Grammatically, most of the verbs used in the conversation are in the present tense, whereas all the verbs used to describe the events are in the aorist tense (cf. Dockery 1988:17). This fact suggests that, when the author portrays the events, he treats them as having definitely happened in the past. However, when he records the utterances, he employs the verbs in the present tense so that the words of the characters may come alive as if they were speaking right now. Granted that the use of the present tense is a conventional way to record utterances, it does cause their conversations to be displayed very vividly, creating more fascination.

4. As Nida and others (1983:44) point out that "compactness is often combined with other rhetorical features, especially parallelism and ellipsis", the same holds for parallelism, in this instance. Phonetic parallelism is found among the main verbs of cola 4 to 10, except colon 9: êimwev, ΙπαίήΟΕν, έΊτέχρισβν (cípev), άττήλθεν and ήλθεν. Syntactic parallelism is also found between cola 4 to 6 and 8 to 10, for these cola have no explicit nominal parts and are connected by the same conjunction και.24 These cola are all linked by means of an additive-different (consequential) relationship. Another parallelism can be detected between subcolon 2.1 and 3.1. These parallelisms are structural evidence for the cohesion of this cluster.

5. Just as Jesus' healing actions were described in three parts, the reactions of the blind man were also depicted in three parts. This contrast may not be a coincidence, but the author's intentional arrangement.

6. As far as this cluster is concerned, my view does not correspond with that of Jones (1997:167) who states regarding verses 6-7 that "the primary focus of attention is on the relationship between healer and the one healed, not on the act itself". The reason for this is that, as will be noted, the work of God through Jesus' healing action should be the pivotal point in this cluster. The relationship between the two will be highlighted in more detail in cluster B' (9:35-38), when the blind man makes his commitment to Jesus.

7. Significant structural markers include the following: blind, (to) sin, (to) work, to send, day, night, light, and to see (sight).

All these aspects contribute to the cohesion of this cluster.

3.3 Microspeech acts

I shall make the following analysis according to the basic reading scheme (cf. section 3.4.2 in Chapter 2).

3.3.1 The first subcluster (9:1-5)

a) General analysis25

Colon 1 is the setting of the event in the narrative structures in which it is told that Jesus and the disciples (by an obvious induction from colon 2), who were walking together on a road somewhere in Jerusalem, saw a man who had been blind from birth. The conjunction κα'ι indicates that this story has some relationship with the previous chapter (Schnackenburg [1968] 1980:240; cf. Brown 1966:371, 376), showing the temporal progression. The present nominative masculine participle ποφάγών indicates, along with the inference from the co-text, that the subject is Jesus.

Subcolon 1.2* is the main clause of the sentence, and portrays what Jesus noticed on the way. The author introduces the blind man to the reader for the first time in this portrait. In subcolon 1.2*, the narrator, by using the prepositional phrase ck γενετής, mentions that the blind man's blindness was congenital.26 This detail 'blind from birth', not merely 'blind', is very important for the plot of the entire story. Thus, this verse 1 renders: And while he was passing by, he saw a man blind from birth.

b) Illocutionary act

The text before us begins with the narrator's voice; the narrator attempts to inform the reader of the setting of the event which is about to take place, as analysed earlier. The aorist indicative verb έίδεν expresses the subject's action with certainty. This implies that the narrator's attitude in describing the setting may be strong. In light of these points, I shall classify this utterance as an illocutionary act belonging to the category of constatives, further subclassified as an informative.27Bach and Harnish (1979:42) present the complete schema of informatives as follows:

Informatives: (advise, announce, apprise, disclose, inform, insist, notify, point out, report, reveal, tell, testify).

In uttering e, S informs H that P if S expresses:28

i. the belief that P, and

ii. the intention that H form the belief that P.

When this schema is applied to the text in this section, the following result is obtained:

In uttering that And while he was passing by, he saw a man blind from birth, the narrator informs the reader that Jesus saw a man born blind if the narrator expresses:

i. the belief that Jesus saw a man born blind, and

ii. the intention that the reader forms the belief that Jesus saw a man born blind.

As the narrator appears to express his belief and intention, as described above, the utterance would be a successful informative speech act.

c) Perlocutionary act

The perlocutionary force of this narration is to get the reader to accept the way in which the story is about to start, because this is the starting point of the event. The story cannot continue, unless the reader accepts the narrator's explanation. Even if the reader cannot determine by himself whether, as the narrator claims, the man whom Jesus saw was really a blind man or not, there is no need to doubt it at this point, because it can be assumed that the Cooperative Principle (cf. section 1.3 in Chapter 2) is now being observed between the narrator and the reader. Moreover, the narrator has no reason to want to lose the reader's confidence in him as a reliable narrator; that confidence that has been established thus far in the first eight chapters. Rather, the narrator needs to re-establish his trustworthiness when he is about to introduce a new story to the reader. In this sense, it is imperative for the narrator to uphold the Cooperative Principle, especially the Maxim of Quality (be true), in order to achieve an adequate perlocutionary act.

d) Communicative strategy

1. At first glance, the narrator seems to break the Maxim of Ambiguity under the Clarity Principle of Textual Rhetoric by not specifically identifying the subject of the sentence, which is Jesus. However, this is not the case in this instance, for the narrator already mentions Jesus' name in the last sentence in 8:59: ήραν oUv λιθους ίνα βάλώσιν επ' αυτόν ΊησαΟς δε εκρύβη και εξήλθεν εκ του ιερου.

2. Although Beasley-Murray (1987:153) suggests that there is a time gap between 8:59 and 9:1, in the narrator's eyes the story in Chapter 9 continues, without a doubt, from the story related in Chapter 8. Thus, he considers it more important to follow the Maxim of Reduction under the Economy Principle by not repeating Jesus' name. This is a basic example of what Leech (1983:67) points out, namely that "the Economy Principle is continually at war with the Clarity Principle".

3. Viewed from the perspective of the continuity from Chapter 8, the narrator further observes the Processibility Principle in the present text. He especially follows its End-Focus Maxim by putting new information, that Jesus saw a man blind from birth, at the end. Many critics29 take note of Jesus' initiative in this miracle story.30 Holleran (1993b:354) represents their opinions, stating that "from the start the emphasis is entirely on his initiative". By contrast, those who are in need usually approach Jesus for his mercy in most miracle stories in both the Synoptics and the Fourth Gospel (e.g., 2:3; 4:47; 11:3).

4. The fact that the narrator does not give an elaborate account of the setting is indicative of his intention to create suspense in the story. This can be explained in terms of the Maxim of Quantity (making your contribution as informative as is required). Is the text under consideration as informative as is required for the story's setting? Generally speaking, one can describe a setting by using the 5 W's: who, when, where, what, and why. A few questions may consequently come to the reader's mind. When did Jesus see this blind man? Which road or where was he walking? Why was he passing by? What was the blind man doing at that time? These are some of the curious questions. The narrator, however, provides hardly any information in a short sentence on the setting. From a narratological point of view, Jones (1997:162) points out that "the comment that he was 'passing by' suffices to denote a change of scene". Obviously, the narrator thinks that this is enough for the reader, at least for the moment. There is no need to doubt that the other side of the Maxim of Quantity is operative: "do not make your contribution more informative than is required" (Grice 1975:45). Because of this textual strategy, the narrator is successful not only in involving the reader in the narrative story with suspense, but also in taking the reader to the heart of the story from the beginning. This strategy enables the reader to focus, even more closely, on the disciples' question in the next verse.

5. As far as the Maxim of Quantity is concerned, the most important contribution by the narrator in verse 1 is the disclosure of the secret of the blind man. The man was blind, and his blindness occurred at his birth. His suffering is , and the theme of suffering is, therefore, introduced at the outset (cf. Boice 1977:35). The reader has no way of knowing this secret, unless the narrator relates it from his omniscient perspective. This bears considerable significance for the development of the story. Without this narration, the disciples' question in the next verse would make little sense. The same holds for the conversation between his parents and the Jews in verses 18-20. Lindars ([1972] 1981:341) is of the opinion that John "wishes to present the healing, not as an act of restoration, but as a creative act by him who is the Light of the World". The narrator enhances and contributes to the reader's understanding of the story to a great extent, while observing the Maxim of Quantity.

6. Regarding the significance of the fact that the accusative noun άνθρώπον has no article, Howard-Brook (1994:214-215) is of the opinion that the absence of the article indicates that this usage can be meant as the whole of humanity, de-emphasising the particularity of the individual - the blind man, in this instance. Duke (1982:182) and Dockery (1988:17) also point out this aspect (cf. Barrett 1955:294). Painter (1986:42) draws attention to the fact that the omission of τίς, which is used in 5:5, and John's choice of word άνθρωπος instead of άνήρ, make this interpretation most likely. If this view is combined with the fact that no name is given to the blind man, this will strengthen the argument (cf. also Koester 1995:64). As far as family life in Palestinian society is concerned, Stambaugh and Balch (1986:84) state: "Sons were named at circumcision." Thus it is logical to assume that the blind man had his own name. But the author in this chapter does not provide his personal name, unlike the chapters that record the names of the individual characters.31 The absence of his name is most likely because the author may intend, in addition to inviting "the reader's subjective identification with the unnamed characters" (Beck 1993:143), to accentuate that all humankind is spiritually blind from birth (until they receive the light which shines in the darkness) (cf. also Pink [1945] 1968:63; Morris 1971:477; Duke 1982:182).

7. Lee (1994:186) warns, however, not to "import the later doctrine of original sin into the narrative". She points out: "In v. 3, Jesus rejects the link between blindness and sin ... " (Lee 1994:186). As will become evident later, when the disciples and Jesus spoke of a possible connection between blindness and sin, they were not discussing original sin as such, but a particular, tangible sin that may have caused his blindness, just as she rightly observes that "the narrative is not concerned with original sin" (Lee 1994:186). However, in my opinion, the point that all are spiritually blind from birth is not an importation of the later doctrine, but an insight gained from both the text and Johannine thought. The author does not give any reason for the existence of darkness in the Prologue, but he presupposes its existence (John 1:5). When the Johannine Jesus stated that "the truth shall make you free" (8:32), Jesus presupposed that the Jews had been enslaved. Jesus even pointed out that they were of their father the devil (8:44). Some scholars32 suggest that, in John, the Jews may be representative of humankind or 'the world', especially of those who sit in darkness. Therefore, the above point corresponds to a prevalent theme in Johannine ideology, and is not the importation of the later doctrine of the Church. Culpepper (1983:191) also agrees, stating that all are born blind in Johannine thought (cf. also Barrett 1955:294; Du Rand 1994:26).

e) Summary

The theory of speech acts successfully determines the narrator's utterance as an informative speech act. The narrator employs the Cooperative Principle and various Maxims (Quality, Quantity, Reduction and End-Focus) to introduce this intriguing story effectively to the reader.33 The theme of suffering is also introduced. The reader should accept the way in which the story began by knowing the information provided by the narrator. The reader is expected to view the narrator as wholly reliable.

9:2 και ήρώτησαν αυτόν oi μαθηταΐ αύτού λέγοντες, Ταββί, τις ήμαρτεν, ούτος η' οι γονεις αύτού, Ινα τυφλός γεννηθή;

In this verse, the basic reading scheme concerns two different utterances: the utterance of the narrator and that of the disciples. I shall first deal with the narrator's utterance.

a) General analysis

The encounter with the blind man made the disciples curious about his blindness. Thus, colon 2 opens the first dialogue that occurred between Jesus and his disciples. In fact, this marks the starting point of both the first subcluster and the happenings of the entire chapter. Accordingly, colon 2 describes the disciples' question to their master, and 2.1 relates the content of their question, with the complementary remark of 2.1.1. Colon 2 is rendered: And his disciples asked him, saying,

b) Illocutionary act

The intention of the narrator is to tell the reader who initiated the conversation and of whom they asked the question. Thus, this utterance also constitutes an informative speech act. The narrator does not provide the detail, as in the previous verse, in order to emphasise the disciples' initiative in striking up the conversation.

c) Perlocutionary act

The reader must notice the identity of the interlocutors and their important role in this conversation (see below).

d) Communicative strategy

1. Intrigued by the miserable situation of the man born blind, the man they also noticed, the narrator introduces the disciples' question. The first matter that needs to be clarified is who were the disciples. How many disciples were walking with Jesus? As pointed out earlier, the reader has some knowledge of the disciples. He knows their characteristics as accumulated by reading the eight previous chapters thus far. This is the reason why the narrator introduces the disciples without any explanation. For an answer to the second question, however, the reader has to infer it from the immediate co-text. As a result, it can only be said that there were most likely not many disciples (Bernard 1928:324 is positive in including the Twelve), because they could hear each other speaking while walking together. However, in the narrator's eyes, these observations are not important, for the narrator also adheres to the Economy Principle in introducing the disciples. He could have furnished more information, but he chose not to do so. What is more important here then? It is agreed that one of the literary characteristics of the Fourth Gospel is that Jesus usually takes the initiative and starts the first utterance of the conversation.34 In this instance, however, the disciples, not Jesus, initiated the conversation. Although Jesus took the initiative in the healing itself, the disciples opened the actual conversation. This is important, and similar to the basic conversational form of the Synoptic Gospels (for a discussion of the dialogue form, cf. Dodd 1963:316-319). Hence, the narrator's introduction of the disciples at this point is very concise and straight to the point.

2. I should note that, from this point onward, I shall omit the reading scheme (except for the section on 'GA') concerning the narrator's introduction to the characters' conversation for the remaining analysis of Chapter 9, since the results will most likely remain similar. The illocutionary act of introduction is mainly informative, providing information such as who the speaker is, and/or to whom does the speaker address himself. The perlocutionary act is for the reader to understand such information in order to decode the speaker's utterance more correctly. The introductory narration is, therefore, important as "stage direction" (Saayman 1992:15), explaining the setting of the particular speech situation. Consequently, the introductory narration will be discussed as part of the usual analysis on each utterance, but not as a separate object of analysis. This kind of introduction can be found in verses 3, 6-12, 15-17, 19-20, 24-28, 30, 34-41.

I shall now examine the disciples' utterance.

a) General analysis

In subcolon 2.1, the vocative noun 'Ραββι is probably the conventional word for the disciples when they tried to get attention from Jesus (cf. Bernard 1928:324). The subject of the sentence is expressed by the interrogative pronoun τις, and the aorist active verb ήμαρτέν signifies the action. This important word provides a base for the formulation of the theme of sin in this chapter (cf. Brodie 1993:357). The disciples thought that the man's blindness must have come from either the blind man's own sin or his parents', because he was born blind. Rensberger (1989:44) is of the opinion that the question as to who is a sinner dominates the entire chapter (cf. also Owings 1983:74).

In 2.1.1, the subordinate conjunction Ίνα and the aorist passive subjunctive verb γεννήθή form a result clause (Barrett 1955:295; Morris 1971:477, footnote 5; Bruce [1983] 1994:209). Its content is the result of the action referred in the main clause. What the disciples really wanted to know was the reason for his blindness out of (e.g., theological) interest, assuming that there should be some relationship between sins and physical affliction. Their thoughts may have reflected the common understanding of the connection between sin and suffering among Jewish people at that time. Semantically, this assumption becomes the underlying focal point in the deep structure of this subcluster (for a discussion of deep structure, see Louw 1982:73, 77). The translation of this utterance (the propositional content) would be: Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, with the result that he might be born blind?

b) Illocutionary act

The disciples' utterance is a question as to the cause or reason for the man's blindness. In speech act theory, an utterance is evaluated not in terms of whether it is true or false, but primarily in terms of success or failure. In order to evaluate the utterance as such, I shall take into account certain felicity conditions. Searle ([1969] 1980:67) provides a scheme of the necessary and sufficient conditions for a speech act of question as follows:

Propositional content condition: Any proposition or propositional function.

Preparatory condition: S does not know 'the answer', i.e., does not know if the proposition is true, or, in the case of the propositional function, does not know the information needed to complete the proposition truly. It is obvious to neither the S nor the H that H will provide the information at that time without being asked.

Sincerity condition: S wants this information.

Essential condition: It counts as an attempt to elicit this information from H.

Since these conditions are the criteria for a successful utterance, I shall examine the disciples' question as follows:

Propositional content condition: It is obvious that the disciples' question satisfies this condition.

Preparatory condition: The disciples do not know the answer. It is obvious to neither the disciples nor Jesus that Jesus will provide the information at that time without being asked.

Sincerity condition: The disciples want this information.

Essential condition: It counts as an attempt to elicit this information from Jesus.

It is obvious from the above that the disciples' question satisfies the above conditions and that it is, therefore, a successful question speech act on the character level. Briefly, the disciples had the intention to obtain information from Jesus which they did not have at the time of inquiry. They sincerely wanted to know who was responsible for his congenital blindness. How they came to know of his condition is a mystery. The author leaves no clue. Regarding the illocutionary force on the text level, the author intends to ask the reader the same question as the disciples did in order to observe whether the reader also shares the same kind of perceptions of the relationship between sin and suffering.

c) Perlocutionary act

Since the disciples' question is a question speech act, this entails that Jesus was brought to the position where he needed to provide a successful answer, because he was legitimately asked according to the rules of language. Accordingly, Jesus should provide a sufficient answer to their question, indicating whose fault it was that caused the blind man to be blinded. The reader should also answer the question for himself, indicating whether or not he also shares the same views concerning the issue of sin and suffering.

d) Communicative strategy

When discussing a character's utterance, we would, as a rule, analyse it on two levels, namely the communication on the character (or story) level and the author-reader (or text) level (cf. section 2.2.1 in Chapter 2). I shall now discuss the communication on the character level.

1. It is noteworthy that the disciples' question may be observing the Interest Principle of Interpersonal Rhetoric. According to Gros Louis's (1982:20) suggestion that it is helpful for a literary critic to ask, "Why does the narrative have this particular character saying these particular words at this moment?", we should also ask why did the disciples ask this particular question of Jesus when they saw the blind man? Was it usual for them to ask that kind of question whenever they saw a person with any physical defect? Even if their question reflected upon the common understanding of the relationship between sin and suffering among Jewish people at that time, as examined earlier (section 3.1.1), it was probably unusual to ask the question explicitly in the way they did. I assume that, when one saw a physically disabled person whom one did not personally know, one's normal reaction would have been just to have sympathy in the first instance. When the disabled person was poor, as in the case of the blind man who was described as a beggar in verse 8, one may also have considered giving alms to the weak person. In fact, "giving alms to the poor was part of normative Jewish piety" (Karris 1990:22). This Jewish practice is reflected in the synoptic Jesus who encouraged his followers to be generous towards the poor (e.g., Mt 5:42; 6:3; 19:21; Mk 6:37; 10:21; Lk 9:13). What is even more fascinating is that "[i]t is the Johannine Jesus, on the other hand, who, along with his disciples, has money and gives alms to the poor".35 It suggests that Jesus and his group appeared to engage fairly often in this pious act (cf. Karris 1990:22-32). In this instance, the disciples only uttered this aloof question, and did not give alms to the blind beggar. This may be unusual, and their question itself could be considered rude. Accordingly, in asking such a question, the disciples may have committed what Pratt (1977:182) calls an "unintentional failure" of the Politeness Principle, especially of the Sympathy Maxim. However, or rather therefore, their question is simultaneously "unpredictable, and hence interesting" (Leech 1983:146). It is tellable and, therefore, observes the Interest Principle at the expense of the Sympathy Maxim.

2. In addition, social-scientific data may shed more light on the disciples' inquiry. "Because people in antiquity paid little attention to impersonal cause-effect relationships and therefore paid little attention to the biomedical aspects of disease, healers focused on persons in social settings rather than on malfunctioning organs in the biomedical sense. Socially rooted symptoms rather than adequate and impersonal causes bothered people" (Malina & Rohrbaugh 1992:71). This may be one explanation for the disciples in 9:2 not being concerned with their sympathy or impression of the man's blindness, but the question addresses a social (and theological) issue.

3. As far as the Cooperative Principle is concerned, the disciples' question appears to fulfill all four maxims. But, is that really the case? Of the four maxims, only the Relation Maxim (be relevant) may need some scrutiny. This Maxim demands relevance of an utterance in a verbal exchange. Is it relevant for the disciples to ask Jesus such a question, namely who has sinned? Did they really expect that Jesus could answer their question? Was Jesus the right person to provide the answer? Did Jesus really know the personal history of the man whom he had just seen on the road? If Jesus was not in the position to answer the disciples' question in any way, their question is considered, what Austin ([1962] 1976:16) calls, a "misfire". This means that their question is not an appropriate one to ask Jesus. This entails either an unintentional failure or a violation of the Relation Maxim on the part of the disciples. However, the disciples seemed to be confident of Jesus' ability to answer the question. It is reasonable to suppose that their association with him up to this event could have made them confident of their master. Since they had already witnessed or heard his signs in his impressive discourses, especially the incident where Nathanael was amazed by Jesus' knowledge (1:47-49), it would not be strange if they had a special confidence in the capacity of his knowledge and deeds. As a result, the disciples were also observing the Relation Maxim.

4. At this point, I shall discuss the communication on the author-reader level. There is one set of important issues left concerning verse 2 before scrutinising Jesus' reply in the next verse.

i. Was it really a normal perception in Jesus' days that physical affliction somehow resulted from one's sinning?

ii. Was it also true in the author's own days?

iii. Is correcting such a view one of the reasons why the author wanted to write this story?

iv. In what way is the motif of suffering employed in this verse?

5. We have already noted the answers to the first and second questions in the section on 'Blindness and sin' (section 3.1.1). Once more, the view concerning the close connection between sin and suffering was common in the days of the characters and of the author. As far as the third question is concerned, Schnackenburg ([1968] 1980:241) states: "The questioners here - and behind the disciples we can see early Christians groups with their questions (cf. 14:8, 22) - are oppressed by a problem to which they know no satisfactory answer." This could be a possible motive for the author to write this story. Schottroff (1998:176) is of the opinion that "[i]n the Johannine communities there were discussions about sexual ethics (9:2-3; 8:37-44) carried on within the framework of the corresponding Jewish discussions. The disciplining of sexual practices within marriage was rejected (9:3)."

6. The way in which the theme of suffering is employed in question iv is unique and subtle. The focus is not on the suffering of the blind man as such, but on the general perception concerning the link between sin and suffering represented by the disciples. Anyone who upheld this common belief, including the characters and the reader, may have suffered from this negative perception of affliction. Once they experienced any form of suffering such as physical deformity, illness, misfortune, disaster, broken family, and even loneliness, they would further suffer as a result of an unpleasant search for the cause. They would be mentally and spiritually tortured. Suffering brought on further suffering. After all, they were living in "a sin-infected universe" (Barclay [1955] 1975:38). This suffering beneath the surface may be even worse. Therefore, as will be noted in the next verse, the purpose of the suffering theme, in this instance, would be corrective (cf. section 6 in Chapter 3) in the sense that the dominant view needed to be challenged and reconsidered.

e) Summary

The disciples queried Jesus about the man's congenital blindness based on the common assumption of the possible relationship between sin and suffering. In order to focus on the issue described in their question, the author makes particular use of the Economy, Politeness and Interest Principles as well as the Relation Maxim. The themes of sin and suffering are still evident in their utterance. I shall now pay full attention to Jesus' answer in the next verse.

9:3 απεκριθη Ίησους, ουτε oUtoj ήμαρτεν ουτε οι γονείς αυτου, αλλ ινα φανερωθή τα εργα του θεου εν αυτφ.

As mentioned in the analysis of the previous verse, the reading scheme of the introduction to the conversation by the narrator will be omitted from this point onwards. The analysis will only be concerned with the characters' utterances.

a) General analysis

Led by the disciples' inquiry, Jesus' answer is provided in colon 3. According to the colon demarcations, colon 3 is supposed to be examined altogether as a unit of analysis. However, his answer in colon 3 can be divided into three smaller units, subcola 3.1-3.2, 3.3-3.4 and 3.5, and each smaller unit can be perceived as a microspeech act. Accordingly, the analysis will be conducted separately on each microspeech act, for it is feasible and profitable to analyse it this way. In conclusion, these microspeech acts will be mapped into a macrospeech act to indicate that colon 3 should indeed be treated as a unit of analysis.

1. Let us scrutinise the first smaller unit, subcola 3.1-3.2. Subcolon 3.1 provides the direct answer to the disciples' question, whereas subcolon 3.2 gives the ultimate spiritual answer. In 3.1, the sentence construction, utilising two of the same negative conjunction ουτε makes it clear that neither the blind man nor his parents were responsible for his blindness. Besides this conjunction, the remaining words in 3.1 are basically the same as the vocabulary employed in subcolon 2.1. Thus, this repetition in 3.1 may emphasise its meaning semantically.

2. In 3.2, the adversative conjunction άλλ' indicates a dyadic-contrastive relation between this and the last subcolon according to Nida's scheme (Nida et al. 1983:103). The subordinate conjunction ΐνβ and the aorist passive subjunctive verb φανερώθή form a purpose clause (Plummer [1882] 1981:204; Bruce [1983] 1994:209). It is also significant that there may be an ellipsis in this subcolon (Barrett 1955:295), since the ΐν« clause is a subordinate clause. Although there are other possibilities (Morris 1971:478, footnote 10; cf. below), it is likely that the Greek verb ήν can be supplied as its main clause. The syntactic ellipsis may "serve to make the text somewhat more concise" (Nida et al. 1983:34).

3. Since "the punctuation and the versification, both added centuries after the original text of the gospel was written, are a form of interpretation" (Temple 1975:173), it is also possible to read the text differently. Newman and Nida (1980:299) suggest that the ϊνβ clause can be taken as result and as purpose.36 Moreover, Temple (1975:173-175) offers an intriguing translation based on the argument that the full stop can be put at the end of subcolon 3.1, and the comma instead of the full stop at the end of subcolon 3.2. His translation reads: "Neither did this one sin, nor his parents. But in order that the works of God be shown in him we need to work the works of the one having sent me while it is day" (Temple 1975:169; Morris 1971:478, footnote 10; Poirier 1996:293-294). In that case, one does not need to account for the ellipsis.

4. My own translation would be along the lines of the customary translation: Neither this man nor his parents sinned, but (it was) in order that the works of God might be manifested in him. This interpretation is better, because it connects Jesus' act of healing more directly with God's works. It is not, as Temple (1975:175) suggests, merely an act of Jesus' compassion. Furthermore, it can provide a more satisfactory answer to the disciples' question, by offering an alternative view to human suffering. Thus, their teacher Jesus directly answered their inquiry in the first part, and a new revelation was bestowed from the perspective of God in the second part. Jesus' answer, in this instance, denied their assumption about the relation between sin and suffering in the man's congenital blindness, and perhaps satisfied their theological interest more than they expected. Jesus' answer may further imply that Jesus was teaching not to limit their minds with stereotyped perceptions. Jesus might have added, "Open your minds, or you shall become like the Pharisees." However, this new revelation (at least to the disciples) easily transcends the boundary of human understanding, yet it may simultaneously represent an eternal truth: the works of God may be manifested in human afflictions. Since this concept contains a profound implication, it could be the pivotal point that binds this cluster together in a strong cohesive manner. Briefly, Jesus' utterance renders: Neither this man nor his parents sinned, but (it was) in order that the works of God might be manifested in him.

b) Illocutionary act

Since Jesus was asked a legitimate question by the disciples, he now had the responsibility of providing a successful answer. Therefore, the illocutionary point of this utterance would be to explain or state. Based on these points, including the above analysis, the illocutionary act of this utterance becomes one of responsive. Bach and Harnish (1979:43) present the schema of responsives as follows:

Responsives: (answer, reply, respond, retort) In uttering e, S responds that P if S expresses:

i. the belief that P, which H has inquired about, and

ii. the intention that H believe that P.

When this schema is applied to the text in this instance, the following is the result:

In uttering Neither this man nor his parents sinned, but (it was) in order that the works of God might be manifested in him, Jesus responds that the man was born blind in order that the works of God might be manifested in him, if Jesus expresses:

i. the belief that the man was born blind in order that the works of God might be manifested in him, which the disciples have inquired about, and

ii. the intention that the disciples believe that the man was born blind in order that the works of God might be manifested in him.

Since Jesus appears to express his belief and intention just as described above, the utterance would be a successful responsive speech act.

c) Perlocutionary act

The perlocutionary act is for the disciples to understand and accept the answer Jesus provided. In fact, Jesus used two steps in order for them to do so. Firstly, Jesus gave them a direct answer to their question in the first clause, denying that either the blind man or his parents sinned in this case. Secondly, Jesus also needed to supply new information concerning the man's blindness in the second clause, which reveals that God would work through Jesus for the sake of the blind man.

d) Communicative strategy

1. On the character level, O'Day (1987:58) rightly observes that, although the disciples inquired about the cause of his blindness, Jesus' answer explained the purpose (cf. also Brown 1966:371). The question then arises: Is Jesus' utterance a violation of the Maxim of Relation? It is a violation, strictly speaking, in that his utterance has no direct relevance to the primary end of the question, but Jesus' answer is still within the permissive range as an answer to them and, therefore, it is still a good and satisfactory answer. In fact, none of the disciples subsequently demanded another reply from Jesus. To put it differently, since the illocutionary act of the disciples' question is to gain information as to who was responsible for his blindness, Jesus answered it by saying that God was ultimately behind it all.37 Hence, it can be mentioned that Jesus' utterance is not a violation of the Relation Maxim.

2. Moreover, as the disciples' question was asked out of theological interest, Jesus answered it from the same perspective. Jesus revealed what God's role was in human affliction. In this sense, Jesus was observing the Maxim of Relation. This is probably an example of Leech's (1983:42) gloss that the Maxim of Relation has been criticised for its vagueness. Leech (1983:42) offers a clearer definition thereof, stating that one should make "your conversational contribution one that will advance the goals either of yourself or of your addressee". In accordance with this definition, Jesus definitely succeeded in upholding the Maxim of Relation.

3. As for the other Maxims, since it is obvious that Jesus was also observing the Maxims of Quantity, Quality and Manner, his answer in this verse was a very successful utterance. Furthermore, Jesus' answer was unpredictable and interesting to the disciples who needed to learn more about spiritual matters. His answer was beyond their imagination, for their question originally demanded only an answer as to whether either the blind man or his parents had sinned. In this sense, his answer contributed towards enhancing the quality of their conversation through the operation of the Interest Principle.

4. In accordance with the three purposes of suffering (cf. section 6 in Chapter 3), the suffering of the blind man is a perfect example of the third purpose (to God's glory). Not only did Jesus verbally do so in this verse, but he also proceeds to demonstrate it in verses 6-7.

5. Regarding the communication between the author and the reader, in colon 3 the author uses Jesus' name for the first time in Chapter 9. The use of his name is delayed for the purpose of the author attempting to focus the reader's particular attention on Jesus' answer.

6. Moreover, the author is observing the Processibility Principle in order to make it easy for the reader to decode Jesus' utterance. For this purpose, the author seems to uphold all three maxims of the Processibility Principle in Jesus' first utterance. Since new information is given at the end of the utterance, the author is observing the End-Focus Maxim. As "complex constituents are placed at the end of" the utterance (Leech 1983:65), the End-Weight Maxim is also being observed. Because negative operators (ουτε...ουτε) precede the other logical elements in the utterance, the End-Scope Maxim is also being adhered to.

7. For the sake of the reader, the author may also be attempting to correct the wrong traditional view concerning the relation between sin and suffering, which the reader may still hold (cf. section 3.1.1). If so, the perlocutionary act for the reader is for him to understand and accept that the cause or reason for human suffering is not necessarily related to sin.

This may be epoch-making or, if not, at least good news for readers of all times. For instance, if a person is experiencing some kind of suffering, he certainly should not need to feel punished by God as people often do. Because such a person sometimes tries to find the reason so desperately, he unnecessarily connects his suffering to wrongs, which he thinks he may have done in the past. However, the author assures the reader through Jesus' words that this is not always the case. There are cases of suffering that God uses to good purpose. This understanding is often hidden for many years from the person concerned. The person suffering not only has to ask God why it happens to him, but also for what purpose it happened. This may cause a great paradigm shift in his perception of human suffering, and it may often reveal part of the reasons for suffering, just as the disciples were told. When one finds a positive purpose in one's suffering, it is possible that one would also find some kind of consolation. This may be the reason why many readers of all times have found encouragement in this utterance of the Johannine Jesus.

e) Summary

In his responsive speech act, Jesus intended to answer the disciples' question, and to provide new information concerning the blind man's suffering. The information comprises the purpose of his blindness. The disciples should understand and accept the answer Jesus provided, because his answer is convincing. The author may be trying to correct the wrong traditional view, which the reader may still hold, and to let the reader know that the cause of or reason for human suffering is not necessarily always related to sin. The reader may be convinced that Jesus was not an ordinary human teacher, for he surprised the disciples and the reader with his answer comprising this unique view. For effective communication, Jesus especially employed the Relation Maxim and the Interest Principle. The author, on the other hand, uses all three maxims of the Processibility Principle for the same purpose.

9:4 ήμας δέί Ιργάζεσθοα τα έργα του πέμψαντός με έώς ήμέρα έστίν έρχεται νύξ οτέ ούδέίς δύναται έργάζέσθαι.

a) General analysis

The second smaller unit made up of 3.3-3.4 (and the third smaller unit in 3.5) elaborates on the concept that the works of God may be manifested in human afflictions described in subcolon 3.2. Subcolon 3.3 mentions the necessity and urgency of doing God's works within the limitation posed by 3.3.1. It is obvious that, in John's Gospel, the one who sent Jesus was God the Father (e.g., 3:16-17, 34; 5:36-37; 7:16-18; 8:28-29, 42). In terms of a shift in grammatical structure for the sake of emphasis, 3.3 is important because only this subcolon throughout this cluster A employs the first person plural pronoun ήμΟς in Jesus' speech. Schnackenburg ([1968] 1980:241) considers it a striking feature (cf. Barrett 1955:295). But, who were 'we' here then? It is most likely that the term we refers to Jesus and his disciples, because he wished to involve them in doing the works of God (cf. 20:21).38 Verse 4 is rendered as follows: We must work the works of the one who sent me, as long as there is day, night is coming, when no one is able to work.

b) Illocutionary act

Although, structurally speaking, Jesus spoke this utterance partially in response to the disciples' question, it does not, in fact, constitute his direct answer to the question. Indeed, this utterance is Jesus' comment flowing from the words 'the works of God' in his previous utterance. Therefore, in this sense, this is not a responsive speech act, but a special instance in which two kinds of illocutionary acts are performed: one is commisive, and the other is directive. The reason will become obvious from the following analysis. The commisive act can be further analysed as a promise. Bach and Harnish (1979:50) present the following schema of promises (where A = action):

Promises (promise, swear, vow)

In uttering e, S promises H to A if S expresses:

i. the belief that his utterance obligates him to A;

ii. the intention to A, and

iii. the intention that H believes that S's utterance obligates S to A and that S intends to A.

When this schema is applied to the utterance, it reads as follows:

In uttering that We must work the works of the one who sent me, Jesus promises the disciples to do the action if Jesus expresses:

i. the belief that his utterance obligates him to do the action;

ii. the intention to do the action, and

iii. the intention that the disciples believe that Jesus' utterance obligates Jesus to do the action and that Jesus intends to do the action.

Hence, this utterance appears to be a successful speech act of promise. As Jesus was superior to the disciples, the directive illocutionary act of this utterance can be subcategorised as a requirement. The schema of requirements, proposed by Bach and Harnish (1979:47), is as follows:

Requirement: (bid, charge, command, demand, dictate, direct, enjoin, instruct, order, prescribe, require)

In uttering e, S requires H to A if S expresses:

i. the belief that his utterance, by virtue of his authority over H, constitutes sufficient reason for H to A, and

ii. the intention that H do A because of S's utterance.

When this schema is applied to the text in this instance, the following is the result:

In uttering that We must work the works of the one who sent me, Jesus requires the disciples to do the action if Jesus expresses:

i. the belief that his utterance, by virtue of his authority over the disciples, constitutes sufficient reason for the disciples to do the action, and

ii. the intention that the disciples do the action because of Jesus' utterance.

As described earlier, this utterance also appears to be a successful speech act of requirement. Howard-Brook (1994:216) comments on this verse, though his terminology is not derived from a speech act perspective, that "the call is not an option but a requirement". Briefly, Jesus had the intention that he and his disciples should do the works of the Father now, for the time was limited. The author also wants the reader to participate in God's work himself.

c) Perlocutionary act

The perlocutionary force of this utterance has two aspects coinciding with each illocutionary force performed. Firstly, as regards Jesus' promise, the disciples should believe that Jesus' utterance obligates him to do the action. Secondly, the disciples should accept the challenge issued by Jesus and carry out the actual work, understanding the urgency of the work. There is an element of warning in this challenge - Jesus tried to warn them in order to get them to work diligently. The reader is also asked to understand the nature of Jesus' mission as well as to participate in his work, by starting to believe in Jesus, if necessary.

d) Communicative strategy

1. Since the communication levels cannot be clearly differentiated in the analysis of this verse, I shall analyse the communication process without distinguishing between these two levels. Jesus' utterance in this verse observes all the Maxims of the Cooperative Principle, except the Manner Maxim. There are basically two possible ambiguous expressions: one concerning the works, and the other regarding the words day and night.

2. To begin with, the word work (both noun and verb) is one of the author's favourite expressions. Barrett ([1955] 1975:5) counts this word thirty-five times in the Fourth Gospel, while the Synoptics use it only sixteen times. The repeated usage suggests that the author has assigned some peculiar usage for the term. In order to ensure this, at least the following verses from my suggested categories should be taken into account (viewed from the author's perspective):

i. In the words of the narrator: 3:19-21.

ii. In the conversation between Jesus and the Father: 17:4.

iii. In the conversation between Jesus and the disciples: 4:34; 9:3-4; 14:10-12; 15:24.

iv. In the conversation between Jesus and the multitude: 6:27-30; 7:21.

v. In the conversation between Jesus and his brothers: 7:3, 7.

vi. In the conversation between Jesus and the Jews: 5:17, 20, 36; 8:39, 41; 10:25, 32-33, 37-38.

Most of the author's use of the word, including the usage in 9:3-4, relates to the divine work done by the Father or Jesus. In fact, out of thirty-four occurrences, only six are used to denote meanings other than the divine works, such as the human deeds. This sufficiently suggests that the author's characteristic usage of this word emphasises divine works. O'Day (1995:653) further categorises John's usage as follows: "'Works' ... has two ranges of meaning ... both of which occur in vv. 3-4. Firstly, as in v. 3, "works" describes what Jesus does as the one through whom God's works are accomplished (cf. 4:34; 10:25, 37; 14:10; 17:4). Second, the Fourth Evangelist also defines God's work as belief in Jesus ... and this is the usage in v. 4." Through Jesus' words, John summarises the definition of the latter's divine work in 6:29: This is the work of God, that you believe in Him whom He has sent. From this observation, the expression 'the works of God' is not ambiguous to either the reader or the disciples to whom Jesus was speaking in 9:3-4 (cf. 4:34; 6:29). Furthermore, notice the repetition of this word, recorded four times in Jesus' answer (vv. 3-4). Needless to say, this repetition emphasises the importance of the works of God as one of the themes in this instance. Smith (1995:165) also contends that the work becomes the principal point.