Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.35 no.1 Bloemfontein 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v35i1.8

Mission to people of other faiths in the Old Testament and Eldoret, Kenya: Some reflections for engaging Muslims within their context

R. Omwenga

Post-doctoral fellow North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa; Adjunct professor: Adventist University of Africa, Nairobi, Kenya. E-mail: omwenga.becky@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The election of biblical Israel in the Old Testament through Abraham and the mandate to represent God to other nations compare to Kenyan contexts of mission to people of other faiths by virtue of strengths and weaknesses. With an aim of providing reflections for contemporary practice, this article goes beyond these strengths and weaknesses by providing suggestions for how mission can be effectively undertaken in Eldoret, Kenya. As a context where mission begins, the Old Testament's experience of engagements to other nations compare closely to the Kenyan experience, yet both lack perfect examples. Idolatry, unbelief and unfaithfulness to God's commandments are some of the factors leading to Israel's and Eldoret's failure to faithfully represent God. This article highlights and discusses these and proposes recommendations for a better paradigm applicable to any Christian church functioning in an Islamic context.

Keywords: Missiology, Mission, Evangelism, Kenya

Trefwoorde: Missiologie, Sending, Evangelisasie, Kenia

1. INTRODUCTION

Mission to people of other faiths is a concept embedded in the entire Bible. By examining the various ways and principles that characterize both the Old Testament (OT) and Eldoret, this article discusses the subject for the purpose of placing mission in its appropriate context within Eldoret. It is within such a context that the varying views regarding the mission of the church to people of other faiths may be understood, assessed and applied.

2. BACKGROUND

According to Kaiser (2001:11), OT mission points to a central action: the act of being sent with a commission to carry out the will of a superior, in this instance God. God engages various persons and offices (e.g., patriarchs and prophets) to undertake different mission errands in the OT. In Genesis 12:1-3, for instance, Abraham was called upon to go to a place unknown to him. God also sent Moses and Aaron to deliver His people, Israel, from bondage (Exod. 3:10-15; Deut. 34:11; 1 Sam. 12:8; Ps. 105:26). The prophets Isaiah, Ezekiel and Jeremiah were among those sent by God to deliver His message to His people (Isa. 55:11, 6:8; Jer. 14:14, 7:25, 25:4; Ezek. 3:5-6).

God is the initiator of mission to people of other faiths, the founder of the nation of Israel, the founder of the New Testament (NT) church and the sustainer of mission throughout human history. In Eldoret, Kenya, a study of selected evangelical churches revealed that the churches were facing challenges such as the inability to nurture new converts, which may be a barrier to carrying out effective mission. Two examples will suffice. On the one hand, these churches were unable to sufficiently address the loss of confidence in the Gospel in a vast majority of their youth who are growing up in a relativistic, pluralistic, entertainment-oriented society (Parsitau 2009). On the other hand, most of the new members of the evangelical churches, who had been ushered into the church by virtue of evangelistic campaigns, remained inadequately equipped theologically (Tennent 2010:28). This article aims to examine the extent to which the churches in Eldoret have the desire to engage Muslims compared to the OT experience.

3. METHODOLOGY

This study uses qualitative triangulation research methods: observation and questions based on participation; interviews including life history, and focus groups (Elliston 2011:142-143). To develop a case study relevant to Eldoret, Kenya, the study focuses on identifying, describing and providing explanations relating to the common themes regarding the evangelical mission to Muslims in light of God's mission in the OT. The creation story, the calling of Abraham, the election of Israel and the exilic testimonials are a few sections chosen to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the OT's mission to people of other faiths that compare to the Eldoret context (Pate 2004:29).

4. POPULATION AND SAMPLING TECHNIQUES

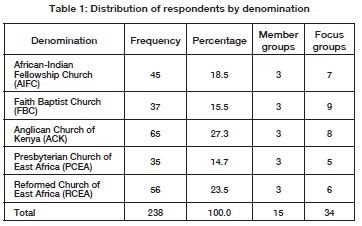

A non-probability purposeful sampling (Tansey, 2007) was used to obtain a sample of informants that helped gather information for how five selected evangelical churches were missiologically teaching Muslims in Eldoret, Kenya. The target population for the study was drawn from the five evangelical churches, with a total of 238 respondents, with three groups of five representatives from men, women and youth departments of the church and 34 focus groups (cf. Table 1).

5. MISSION IN THE OT

The OT narrative on mission to people of other faiths is too extensive to be fully represented in one article. To meet the objective, this article selects five examples of practices and engagements by both God and His chosen nation, Israel. These include, but are not limited to, the creation of Adam and Eve, the call of Abraham, the covenant and election of Israel, universal blessings in Psalms, the exilic testimonials (Naaman, Daniel, Shadreck, Misheck and Abednego, and Jonah the reluctant prophet).

5.1 Creation of Adam and Eve

Man's involvement in the process of those created in the divine image took the form of a command (Gen. 1:28). Giving commands is God's way of engaging His agents in His mission from the beginning to the end. According to Keck (1994:345-346), the first divine words to human beings were about their relationship, not to God, but to the earth. Adam and Eve shared in the one who possessed or exercised creative power (dominion), namely God, the creator. The creative involvement gave the pair a care-giving and nurturing act, as opposed to an act of exploitation (Keck 1994:346).

God's blessings (Gen. 1:22, 2:3) indicated that His power and strength formed an integral part of the power-sharing image, a giving-over of what is God's to others to use as they will. In Genesis 1:26 and 9:1, God determined to renew His commitment to men after the flood to show His intended purpose towards men from the beginning to the end.1 Before the fall, everything God created was perfect (Barton & Muddiman 2001:42; cf. Gen. 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 52). Man's mission included a service both to God, the creator, and His creation. However, the fall in Genesis 3 resulted in curses and promises that changed perfect created beings to imperfect ones (Gen. 3:15). This resulted in an act of love, salvation by grace, a sin-offering and sacrifice both to God and fellow men (Farmer 1998:364), hence a new understanding of mission engagement to people of other faiths applicable both in the OT and in Eldoret, Kenya.

5.2 The call of Abraham

Abraham's divine call would result in a blessing for him, his family and all the nations on earth (Gen. 12:1-3). This came at a time when people on earth faced divine judgement (Gen. 3:15). Through Abraham, God had a divine programme to glorify Himself, thus bringing salvation to all creation. This is the beginning of mission when understood within the context of both the sending command and the blessing in God's Great Commission in the Bible (Kaiser 2001:13). The blessing given to Abraham (Gen. 12:1-3) compares to that given to Adam and Eve (Gen. 1:28) in that there is a command to be fruitful and increase in number, and to fill the earth and subdue it.

5.3 Covenant and election

Grant and Wilson (2005:21) define covenant as an "agreement", "contract", "treaty", or "commitment" between two or more parties. Accordingly, such an agreement may create a new relationship between the parties, or formalize a relationship that already exists. Biblically, making a covenant was a serious matter. In Genesis 12:1-3, God entered into a binding covenant with Abraham for the nation of Israel. This covenant relationship spelled Israel's strict allegiance to one God, Yahweh, and bound them to a strict religion, monotheism.

The election of Israel relied not on favouritism, but was a gift subject to their obedience, so that the covenant promise could be fulfilled (Gen. 24:7; 50:24-25; Exod. 13:11; cf. Hebrews 6:17). Deuteronomy 7:7-8 spelled out the basis for Israel's election as God's representatives on earth:

The Lord did not set his affection on you and choose you because you were more numerous than other peoples, for you were the fewest of all peoples. But it was because the LORD loved you and kept the oath he swore to your forefathers that he brought you out with a mighty hand and redeemed you from the land of slavery, from the power of Pharaoh, king of Egypt.

According to Routledge (2008:171), the people were chosen and saved by grace. God took the initiative to choose Israel and redeem the nation from bondage in Egypt in a profound act of sovereign grace. He took this people to be His own and committed Himself to them. This act of God drawing people to Himself, despite their disobedience, sets the foundation of mission to people of other faiths.

The priest in Israel was an intermediary, representing God to people and the people to God. He was consecrated in the service of God, and granted special access to God's divine presence. There he offered sacrifices, both for himself and on behalf of the people, and presented the prayers and petitions of the nation to God. Priests also brought God's word to the people. The priest was a man of the Law (Torah), who passed on and interpreted God's teaching. This dual role of teaching the Law and offering sacrifices on behalf of the people was defined by the blessing of Levi (Deut. 33:10; Routledge 2009:172).

As a priestly kingdom, Israel was set apart from the nations to be an intermediary, to bring the nations closer to God by sharing the light of God's revelation and the good news of his salvation, and to bring God closer to the nations. Israel's role in the OT was mainly passive. They were called to be holy and distinctive: a people among whom God's presence would be seen, and to whom other nations would be drawn, seeking to share Israel's relationship with God. Several passages refer to other nations being drawn to God through His people (Isa. 60:1-3; Zech. 8:23).

5.4 Universal blessings in Psalms

The call upon God to bless and make Israel prosper with their families, cattle and crops (Ps. 67, 96, 117) justifies the psalter's plea that the nations may look on Israel and say that what Aaron had prayed for by virtue of God's blessing had indeed occurred (Kaiser 2003:31). As a chosen nation, Israel acted as a centre of mission where other nations came to receive blessings. This way of doing mission to people of other faiths is called centripetal (Bosch 1980:78-79; cf. Grant & Wilson 2005:67). Jerusalem was significant in centripetal mission in the OT's universalistic passages. Israel's role in Jerusalem entailed her participation in the courtroom to witness in the case between God and the nations (Isa. 42:1), because Israel had no message of her own to deliver except that from God.2

5.5 Exilic testimonials

The OT records several persons from other faiths who came into contact with the God of Israel. Some examples are presented to validate missionary engagements in the OT.

5.5.1 2 Kings 5:1-19 Naaman's maidservant

The OT abounds in stories and works of God's faithful servants engaging directly or indirectly in sharing the truth in foreign lands. Besides the prophets, who were directly assigned the task of communicating God's messages and warnings to the leaders of both Israel and other nations, there were other individuals whose faith left the mark of their theology and understanding of God's mission in the OT on unbelievers. One of these individuals was a servant girl, who had been taken into captivity and made a slave to Naaman, a commander in Syria (2 Kgs. 5:2). Although hardly anything is written about this servant girl's background, the cultural context emphasizes her gender, her status as a servant, and her position in society as a captive. Her faith leads her master to find healing and his ultimate belief in Yahweh - the God of Israel.

It is thus clear from this rendition that God's mission is not dependent on personalities. Neither is He a respecter of persons. The following questions beg for answers. Why would God fail to send His prophet Elisha directly to Naaman to perform his healing miracles? Why would God use the faith of a young girl and that of the servants in Syria when there were many respected persons in Israel who would have procured the healing in a "respectable and most appropriate way in the eyes of human beings"? Why would Naaman be required to dip seven times into the river Jordan instead of the prophet speaking a word of healing upon him? Why would she have to travel all the way to Israel and not be healed in Syria? Ultimately, 2 Kings 5:5-17 states that Naaman confessed his faith in Yahweh and pledged his allegiance to no other god, except the God of Israel. Despite these challenges, this is an indication that Naaman would probably follow in the footsteps of the patriarchs and prophets and be counted as one of those faithful servants of Yahweh in the history of the OT's mission.

5.5.2 Daniel 3: Daniel, Shadrack, Meshach and Abednego

The account of Daniel and his companions in Babylon offers insights into faithfulness and mission that still remain relevant after twenty-six hundred years. The focus is on how God turns bad into good in this experience of four teenagers. Through no fault of their own, they were exiled to a foreign country. Yet, because of their unswerving commitment, God was able to use them as witnesses for His purposes and power. Through various ordeals, such as a fiery furnace and a den of lions, God not only displayed His care for Daniel and his friends, but He demonstrated His power in front of pagans who knew only their idols. Who but God knows the eternal results of the faithfulness displayed by these young Hebrews?

In a world full of knowledge, philosophy and theology, the four young men stood out as instruments of God's mission. Their experience stands out as a test of true stewardship in a foreign land where one has few if any choices to make. Already in Babylon and in exile, the four Hebrew boys knew that their lives depended wholly on God, the Lord of their forefathers. Commenting on their first test, Steinmann (2008:100) states explicitly that these young men in their early teens demonstrated their ability to withstand the pressure of a foreign culture to compromise their faith.

A spiritual foundation is important, as it plays a big role in the lives of God's people. When God called Abraham out of pagan practice and covenanted with him, His goal was mapped out not only for Abraham's own sake, but also for that of his descendants. God's intention beats all the intentions of men and His ways cannot compare to the ways of men. One of the ways in which Abraham's descendants had to practise their faith before God was through obedience to His commandments. Their children had to be instructed in these commandments on a daily basis and they had to be passed on from generation to generation (Deut. 6:6-7; cf. 4:9).

The parents of Daniel, Shadrack, Meshach, and Abednego could not have predicted what would happen to their children. However, through faithful, daily religious instruction, they provided a strong spiritual foundation for their children. It is important that contemporary parents seek to do the same for their children. The constant dwelling on God, the constant recounting of the miracles, the goodness, and the love of God can be of as much benefit to the parents as to the children. Even for those who do not have children or for those whose children are gone, it is important to keep the reality, goodness, and power of God before us at all times. After all, how can we share with others what we, ourselves, have not experienced? How can God's mission be a reality to the people of other faiths unless it is a reality to God's people?

5.5.3 Jonah 1-4: Reluctant prophet/missionary

The drama unfolds with God demonstrating His will by calling on Jonah (1:1) to undertake His mission (Jonah 1:2) in a foreign land (Nineveh). Unlike Abraham (Gen. 12:1), Jonah did not obey God, which was not new in Israel. According to Keck (1996:480-481), Jonah's resistance to the call from Yahweh is not unique. Moses shrank from speaking to Pharaoh (Exod. 3:10-4:17); Elijah fled from denouncing the regime of Ahab (1 Kgs 19:1-18); Jeremiah recoiled from prophesying to the nations (Jer. 1:4-10). Yet Jonah exceeds them all in his defiance.

Jonah understood the true meaning and consequences of God's mission to people of other faiths. He knew God as the creator, redeemer and merciful. Lessing (2007:348) acknowledges that, even though Israel was the rightful owner of God's blessings through Abraham, God's mercy and love would extend to people of other faiths as beneficiaries of His perfect will. While bitterly resenting the fact that God loved evil people (not because of their evil, but because of their humanity), Jonah attempted to steal the right of God's mission towards the salvation of the people of other faiths (Carson et al. 1994:814). Like many missionaries and church ministers nowadays, Jonah's attempt to block God's mission by refusing to undertake the divine assignment of preaching to the Ninevites was not only an attempt to rob God of His supremacy in His mission, but it also showed how ungrateful and selfish saved human beings can be.

In Jonah 4, God rebukes Jonah's selfish attitude and reluctance. Earlier Jonah was punished for failing to obey and to go to Nineveh immediately (Jonah 1:6-2:1-10). The stern rebuke in Chapter 4 is meant to help many people like Jonah who harbour the same motives and attitudes towards God's mission to people of other faiths. Kaiser (2001:69) contrasts Jonah's selfish attitude with that of the Lord. While Jonah violently opposed anything that would diminish the threatening judgement upon the people of Nineveh, the Lord, who is long-suffering and never willing for any to perish (Jonah 4:2; Joel 2:13; Ps. 103:8), repented His words and changed His judgements (Dunn & Rogerson 2003:700). This narrative has missiological implications for Jonah as a prophet of God and for the church as his agents on earth, and especially for the salvation of the Gentiles. Stuart (1987:479, 499-510) mentions that Jonah deserved to die and not to be delivered. Nevertheless, Yahweh demonstrated his gracious deliverance by intervening in a special way in Jonah's life. That is God's unconditional love. The other moral lesson concerns the attitude of Jonah and the church towards the forgiveness and sovereignty of the Lord. According to Stuart (1987:496), God does not exercise His power arbitrarily and indiscriminately.

When Ninevah heard the message, they immediately declared a fast and put on sackcloth to signify their sorrow and repentance (Luke 3:8). Lessing (2007:300) points to their sincerity, which he says was confirmed by Christ when Christ promised that the Ninevites will arise on the day of judgement to condemn all the unbelievers (Matt. 12:41). Lessing (2007:301) adds that the Ninevites believed in the triune God, so they believed by grace alone and were justified by faith. It is, therefore, tenable to assert that people of other faiths in the OT became the beneficiaries of the blessing promised to Abraham.

5.6 Summary of the OT's strengths and weaknesses

The following strengths suffice from the OT mission. OT mission presents success stories:

- In the person of Abraham whose faith led to the covenant between him and God and Israel's election as a chosen nation.

- In the story of Naaman's maidservant whose acts of bravery led to the healing of Naaman and his subsequent decision to follow Yahweh.

- The four Hebrew boys, Daniel, Shadrack, Meshack and Abednego, for strictly adhering to monotheism and refusing to practice idolatry in Babylon.

- The faithfulness of Yahweh to the covenant between Him and Abraham; obedient individuals such as Abraham, Noah and David in Psalms where people of other nations come to worship Yahweh for His blessings upon Israel.

Despite these strengths, OT mission lacks a perfect example of engaging people of other faiths due to:

- Idolatry. Israel's continued worship of idols from their neighbours went contrary to the will of Yahweh. This prevented their neighbours from coming to worship Yahweh, the creator of heavens and earth. On the contrary, it encouraged polytheism instead of monotheism.

- Disobedience. Israel's failure to keep the commandments of God resulted in their captivity and subsequent withdrawal of God's presence from them. The captivity story was Israel's failure to represent God at its best.

- Unbelief is another weakness that made mission difficult in the OT. Jonah's story presents both the unbelief of Israel and all those who take God's commands in vain. Israel's unbelief in the wilderness, despite many miracles to save them, led to their defeat and the defamation of Yahweh.

6. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

This study points out certain contrasts, commonalities and shared assumptions in the OT's mission engagement to people of other faiths with that of Eldoret, Kenya. From the data collected, the participants' views on engaging Muslims in Eldoret differed in theory and practice. The participants were asked the following questions:

- Are the selected evangelical churches engaging Muslims in Eldoret?

- How relevant is the engagement?

- Is there training of members on mission engagement?

- What aspect of church leadership is most effective in issues of mission to Muslims?

Participants' responses outlined the following aspects of engagements.

6.1 Evangelical church engagement and relevance to Muslims in Eldoret, Kenya

Out of a total of 238 participants, 57.6% reported that there was indeed church engagement to Muslims. The remaining 42.4%, mostly belonging to the Reformed Church, stated there was no engagement. Reasons for engagement were varied. For example, RCEA participants indicated that Muslim engagement with the Gospel demonstrated that Christians had knowledge, that mission is Christ's, and that Muslims were not on the right path. The majority of the participants, however, cited the Great Commission in Matthew (28:18) as the basis for mission to Muslims in Eldoret. On involvement, 88.7% of the participants indicated that they were not involved in engaging Muslims. They indicated that other church programmes seemed more important than mission work to Muslims. There was a small 11.3% who were commited to engaging Muslims. These included youth, women and individual church members who understood the role of the church to people of other faiths.

6.2 Ideological differences

Belief in the singleness and unity of Allah (Tahwid)3in Islam challenged the doctrine of Christian salvation in every way. Of the participants, 20% cited the belief that God did not give birth to a son or that God cannot be given birth to as a barrier to preaching the gospel in Eldoret;4 80% of the participants did not understand the doctrinal differences arising from the belief in Tahwid, but cited differences in the belief of both Allah and God as problematic. Participants reiterated their belief in Christ Jesus - the Son of God (John 3:16) as the only way to salvation.5

Participants indicated a lack of understanding the doctrine of the Trinity among Christians. They wanted the churches to remedy the situation by equipping members with vital truths regarding the doctrine of the trinity.6 Participants decried the laxity among the clergy to address ideological issues among its members. They reported that the differences between ideologies in Islam and Christianity could not be resolved, unless there was goodwill among the leadership to provide direction and proper teachings.

As discussed earlier, the OT's engagement between the Hebrew boys in Daniel 3 is a good example of ideological differences between the nation of Israel and the Babylonians who worshipped idol gods. There are currently still ideological differences in the OT. It requires wisdom and a thorough knowledge of God's mission in order for God's people to participate in this mission.

6.3 Attitude

The attitude of Christians in Eldoret rested upon their belief that the church was not equipped to undertake a missional task to their Muslim neighbours. They perceived that Muslims were hard, difficult, terrorists, unfriendly, secretive and Jihadists. They reported that Muslims would do anything to avenge their image, if provoked.

As a result, the majority of the participants (56.5%) expressed natural hate towards Muslims and the Islamic religion. Some (22.3%) sympathized with them, but felt that there was no need to engage with them, insisting that they had already chosen a religion that leads to God.7 Others (19.0%) wanted to preach to the Muslims, but they were forbidden to do so by cultural differences and practices such as mode of dress for Muslim women, eating food (meat) especially slaughtered by Muslims alone, facing Mecca while praying and the entrenchment of the Kadhis' courts in the constitution. Less than 2% of the participants did not know what to do.

Attitude issues in engaging people of other faiths were outlined in the story of Jonah. Like the Kenyan Christians, Jonah understood the call to the Ninevites as a commission from the Lord. Yet, when it came to presenting the message, Jonah wanted to dictate to God as to how He should deal with the situation. Unfortunately, God was aware of Jonah's attitude and sought to save His people (the Ninevites) despite Jonah's attitude, and taught Jonah a lesson that applies to any generation. Jonah's experience should remind the evangelical churches in Eldoret that God is the owner of mission, of the Muslims and of the Church. They should feel privileged to participate in this mission (Bosch 2009:393).

6.4 Leadership

A distribution of participants, according to status in the church, indicated 58.8% of youth engagement, 28.6% of women engagement, and 12.6% of leadership engagement. The latter figure was a paradox, because congregational members generally expect church leaders to be at the forefront in seeking to fulfil the church's responsibility regarding mission to people of other faiths.

Respondents cited that leaders' inadequate missiological perspective resulted from internal wrangling, disunity among themselves, nepotism and tribalism within churches, financial misappropriations, poor training, and lack of personal commitment to the Lord Jesus. The respondents disapproved of their leaders' attitudes towards change and the acquisition of new knowledge, stating that these leaders were not willing to learn from their neighbours' new ways in which to engage Muslims. They reported that leaders neglected to include children, women and the youth in mission programmes, yet that these groups directly influenced the Muslims in society.

6.5 Cooperation versus individual engagements

The Kenyan evangelical churches context presented little in terms of cooperative engagement to reach out to Muslims. When asked if the churches were implementing programmes to engage Muslims corporately, 52.4% answered "No"; 20.6% answered "yes", while 27% were not sure. Most of the report involved a few individuals who had the passion to engage Muslims on their own. Some departments within churches organized crusade activities on their own to engage Muslims. The youth department (28.6%) and the women's department (12.6%) engaged Muslims in different forums such as sports clubs and green markets. However, respondents complained that such programmes hindered the Muslims rather than engaged them for Christ. Other individuals organized public debates, but, as some respondents noted, such meetings bore little or no results, given the lack of knowledge in the issues discussed.

6.6 Training/sensitization

Discipleship of members for the role of engaging Muslims forms an integral part of the Great Commission according to the Lord Jesus. Matthew 19:28 gives clear instruction to the followers to go and make disciples of all nations.8

Out of the 238 participants, 71.4% indicated that churches in Eldoret were not training its members on how to take mission to Muslims. Reasons for this failure were given as lack of goodwill from top leadership; few or no trained personnel on Islamic issues and relevance; poor programmes targeting people of other faiths; priority given to other church activities at the expense of mission; youth grappling with their own issues such as poverty, immorality and HIV/AIDS, and disunity among churches.

Of the 27.6% of the participants who indicated that there was training, FBC had the highest percentage (22.6%), followed by AIFC (3%) and RCEA (2%), while ACK and PCEA indicated no training at all. The churches that trained their members reported high turnout of Muslim converts. This can be validated by the FBC's highest report on Muslim background believers recorded at 10, as compared to ACK's report at zero.

Some participants in Eldoret indicated that success in engaging Muslims could be realized if churches emulated the OT's context of sensitization. The OT presents no formal training on engaging people of other faiths. Implicitly, the school of the prophets prepared servants for God's work throughout the ages in the OT. Such training was aimed at correcting and warning against disobedience in Israel. Other information was passed down from generation to generation with clear instructions that echo the way in which Muslims train their children.9

6.7 Cross-cultural differences

Participants in Eldoret pointed out culture as a major stumbling block in engaging Muslims in mission. They mentioned practices such as dress, rituals accompanying prayer (Udhu), handling of food (the doctrine of halal and haram), as well as laws and rules governing divorce and re-marriage. A lack of understanding and appreciation of these cultural beliefs and practices prevented Christians from engaging Muslims. The participants argued that Muslims strictly adhere to their culture and religion. Asked whether Christians did not adhere to their own way of life and practices, respondents mentioned that Christians followed the Bible and that Muslims followed the teachings of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and the Qur'an. These cultural practices replicated those of the African traditional beliefs, were contrary to the teachings of scripture and made interaction difficult.

6.8 Fear and persecution/crisis management

There was a general perception that Muslims were terrorists and hence difficult to be reached with the gospel. Stories and experiences of Christians who had attempted to engage Muslims in other places in sub-Saharan Africa such as South Sudan, Somali and Ethiopia were recounted. The conclusion was that it would be futile to engage Muslims with the gospel. The perceptions were exacerbated by the political engagements of purists' forms of Islam such as the Al-qaeda and Al-shaabab in the region and especially following the terrorist attacks of the Al-shaabab on churches throughout the country.10

Participants in Eldoret expressed fear and sensed potential persecution by terror groups associated with Islam. Like the children of Israel in the OT when Moses sent the twelve to spy out the land, their report of the minority Muslims in the country indicated hesitance and terror. OT's account of ten men was filled with intimidation and fear. Eldoret participants were not different.

7. IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATION

Reflections on comparative features between the OT and Eldoret mission to people of other faiths reveal the following issues that require a paradigm shift. They are, but not limited to purpose of mission as outlined in the Bible; the incorporation of training programmes; context, and cultural relations.

7.1 Purpose

Based on the results and on God's examples of mission in the OT through the creation of Adam and Eve, the call of Abraham, covenant and election of Israel, universal blessings in Psalms and the exilic testimonials, the article suggests the following recommendations to meet the purpose of mission:

- Those engaging with people of other faiths should not fear, because Christ promised to be with them throughout the process. Both Israel and the Christians in Eldoret are God's elect. Their engagements to people of other faiths depend on God who owns mission.11

- Obedience to God's commands is mandatory in order to realize the goals of mission. Israel disobeyed God; they wandered in the wilderness and ended in captivity. Eldoret Christians must learn to obey God's voice. The Great Commission provides a conditional promise to obedience to go (Matt. 28:20).

7.2 Programmes

There is a paucity of programmes designed to take the Gospel to people of other faiths. This gap could be filled by means of dialogue, friendship evangelism, Sunday School curricula, sports events for the youth, and Bible Studies.

7.3 Context

Muslims in Eldoret should be identified in terms of their context, where they are, what they are doing and for what reasons, because they form part of God's creation. Outreach activities should be contextualized to include helping the poor in society, praying for the sick, and giving hope to the broken-hearted. Church pastors, evangelists, missionaries and Christians should preach the gospel of love. Every Christian should establish friendship with their Muslim neighbours. Worship songs and prophecies should call upon people of other faiths to praise and worship God who delivers through His Son, Jesus Christ.

7.4 Cross-cultural relations

Christians must learn to appreciate Islam as a way of life in order to value Muslims. All church members must be trained on the doctrines of the church, so that they know how to relate well with Muslims.

Christians should also allow Muslims in their social, political and cultural life. Cross-cultural relations between Muslims and Christians should be improved by means of dialogue. Churches should also improve relationships by studying the culture of Muslims. All those aspiring to be missionaries and pastors must follow courses in cultural anthropology. Education should include the understanding of the Qur'an. Theological Schools and Bible Colleges should teach their students about mission work.

8. CONCLUSION

Mission to people of other faiths is a mandate of God, by God and for God, the creator, redeemer and sustainer of all life. Mission in the OT entailed God's revelation through His acts of creation and His chosen nation, Israel. However, Israelites, who were chosen by God to represent Him in this arena, failed to obey His commands and hence their inability to show a success story to the people of other faiths. However, the exemplary faith of Abraham, the three Hebrew boys and other exilic faithfuls is reported in the OT. Jonah, the reluctant prophet, demonstrates a common current human attitude towards God's work. Although Israel failed in their ways, God kept His promises to Abraham and renewed His covenant with Israel. This was fulfilled in the NT. In Kenya, mission to the Muslims by the selected evangelical churches revealed an ongoing, slow and disjointed process. Like the nation of Israel of the OT, the selected churches failed to fully engage the Muslims. They faced various challenges including lack of proper leadership; negative attitude; cross-cultural intolerance; fear of persecutions, and ideological differences. By comparing OT mission with Eldoret mission, the article concludes that engaging people of other faiths is mandatory. It also makes recommendations that could be replicated by those working within Muslim contexts in Kenya.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barlas, A. 2004. The Qur'an, sexual equality, and feminism. [ Links ] [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.asmabarlas.com/TALKS/20040112_UToronto.pdf [2014, 23 July].

Barton, J. & Muddiman, J. (eds.) 2001. The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bosch, J.D. 1980. Witness to the world: The Christian mission in theological perspective. Atlanta, GA: John Knox. [ Links ]

Bosch, J.D. 2009. Transforming mission: Paradigm shifts in theology of mission. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Boyle, N.H. 2006. Memorization and learning in Islamic schools. Comparative Education Review, Chicago Journal 50(3):478-495. [ Links ]

Carson, D.A., Guthrie, D. & Donald, J.S. (eds.) 1994. New Bible Commentary: 21st century edition. Downers Grove, ILL: InterVarsity Press. [ Links ]

Dunn, D.G. & Rogerson, W.J. (eds.) 2003. Eerdmans commentary on the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Elliston, J.E. 2011. Introduction to missiological research design. Pasedena, CA: William Carey Library. [ Links ]

Farmer, R.W. (ed.) 1998. The international Bible commentary: A Catholic and ecumenical commentary for the twenty-first century. McEvenue, S. et al. (eds.) Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press. [ Links ]

Grant, A.J. & Wilson, LA. (eds) 2005. The God of covenant: Biblical, theological and contemporary perspectives. Leicester: Apollos. [ Links ]

Kaiser, c.W. Jr. 2003. Mission in the Old Testament: Israel as a light to the nations. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker. [ Links ]

Keck I.E. 1994. The New Interpreter's Bible: General articles and introduction, commentary, and reflections for each book of the Bible, including the Apocryphal/Deuterononical books. Twelve vols. Nashville, TN: Abingdon. [ Links ]

Lessing R.R. 2007. Concordia commentary: Jonah. Saint Louis, MO: Concordia Publishing House. [ Links ]

McGavran, A.D. 1980. Understanding church growth. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Nzwili, F. 2014. Facing Alshaabab attacks, some Kenyans call for Somalia withdrawal. The Christian Service Monitor. [ Links ] [online.] Retrieved from: www.CSMonitor.com [2014, 5 June].

Parsitau, S.D. 2009. Keep holy distance and abstain till He comes: Interrogating a Pentecostal Church's engagement with HIV/AIDS and the youth in Kenya. Africa Today 56(1):45-56. [ Links ] [Online.] Retrieved from: http://muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&summary [2015, 4 March].

Pate, c.M., Duvall, J.S., Hays, D.J., Richards, E.R. Jr., Turker, D.W. & Vang, P. 2009. The story of Israel: A biblical theology. Downers Grove, ILL: InterVarsity Press. [ Links ]

Rendtorff, R. 1989. 'Covenant' as a structuring concept in Genesis and Exodus. Journal of Biblical Literature 108(3):385-393. [ Links ]

Rendtorff, R. 1998. The covenant formula: An exegetical and theological investigation. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

Routledge, R. 2008. Old Testament theology: A thematic approach. Trowbridge: Cromwell Press. [ Links ]

Stuart, D. 1987. Hosea-Jonah. Word Biblical Commentary 31. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. [ Links ]

Tansey, O. 2007. Process tracing and elite interviewing: A case for non-probability sampling. Political Science and Politics 40(4):1-23. [ Links ] [Online.] Retrieved from http://observatory-elites.org. [2015, 4 March].

Tennent, C.T. 2010. Invitation to world missions: A trinitarian missiology for the twenty-first century. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Academic & Professional. [ Links ]

Zimmerli, W. 1964. The place and limit of the wisdom in the framework of the Old Testament theology. Scottish Journal of Theology 17(2):146-158. [ Links ] [Online.] Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0036930600005780 [2014, 23 July].

1 The primeval history in Genesis 1-11 presented a perfect beginning of "everything" (Gen. 1:31), on the one hand, and a contrast of a "corrupt" (Gen. 6:12) earth, on the other. Like the promise accompanying the curse in Genesis 3:15, the exception given to Noah in Genesis 6:8, "but Noah found favour in the eyes of the Lord", provided humanity with a second opportunity to participate in God's mission. The parallelism in the Hebrew text of the two passages was evident and obviously intentional, according to Rendtorff (1998:386). The word "covenant" spoken to Noah in Genesis 6:8 spells God's decision to spare Noah and all living beings that enter the ark with Him (Gen. 6:19). This is linked to Genesis 9 where the term "covenant" in relation to humanity is developed. This is where God continues His mission engagement with men in the OT after the fall.

2 Psalms 67, 96 and 117 present Israel's function as a witness rather than a proselytizer, because God will be drawing and bringing the nations to himself. If Israel will simply be the Israel of God, the nations will be drawn to him.

3 "For instance, the Qur'an teaches that God is one and God's sovereignty is indivisible; this is the doctrine of Tawhid or divine unity" (Barlas 2004:5). http://www.asmabarlas.com/TALKS/20040112_UToronto.pdf.

4 Muslims believe in Jesus Christ as a prophet and not as the Son of God. This raises issues on ideology, because it touches on the way of salvation. The teaching that God cannot give birth or be born (Qur'an, Sur 112:3) is a serious teaching in Islam that touches on the belief in the unity of God (Tawhid) and anyone subscribing to any other teaching is considered a blasphemer.

5 The participants confirmed that, because Muslims know Jesus only as a prophet (Qur'an, Sur 4:171; cf. Sur 66:12) and deny (John 1:29) Him as the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of men, Christians can only convert the Muslims by virtue of friendship.

6 It was clear from the point of view of the participants that the doctrine of the Trinity, like that of the Tawhid, was not only technical, but also problematic. Such ideological dilemmas made preaching to Muslims a deterrent.

7 Some participants indicated that Islam is a religion compared to Christianity. There was thus no need to preach to Muslims.

8 'All' includes Jerusalem, Judea, and Samaria and to the ends of the earth (Acts 1:8). Geographically, we may speak of Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Linguistically, we may also speak of Americans, Africans, Asians, or Europeans. Religiously, we may speak of Christians, traditionalists, Buddhists and Muslims.

9 Drawing on data from field research in Morocco, Yemen, and Nigeria. Boyle (2006) mentions that Qur'anic memorization is a process of embodying the divine - the words of God. The mission of contemporary Qur'anic schooling, with Qur'anic memorization at its core, is concerned with developing spirituality and morality.

10 In August 1998, the US Embassy buildings in Kenya and Tanzania were bombed, causing at least 250 deaths. The attack was directly linked to Osama bin Laden. Since then, Kenya has witnessed several terrorist attacks, the latest being witnessed in public places including churches in Nairobi and Mombasa cities (Nzwili 2014).

11 "The faith of the Old Testament has its origin in the fundamental fact that God encountered Israel in the OT. The preamble of the decalogue mentions it: 'I am Yahweh thy God, which brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage' ... Israel knows that her God encountered her not in a reaction but in a free divine action in history ... He laid hold upon Israel, called her and made her His people ... this previous deed of God came to be designated by the term 'election of Israel' ... His free grace proves to be the God who stands by the independence of His election" (Zimmerli 1964: 146).