Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Theologica

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.35 no.1 Bloemfontein 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v35i1.2

A cognitive semantic approach to Redeemer (Gō'ēl) in Deutero-Isaiah

S. Ashdown

Faculty of Hebrew and Old Testament Studies, Applied Linguistics Department, Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics, Dallas, Texas. E-mail: shelley_ashdown@gial.edu

ABSTRACT

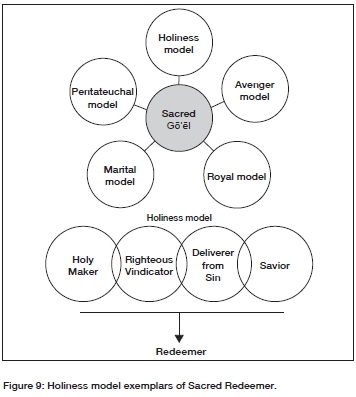

This study draws on cognitive semantics to explore the radial category nature of Redeemer (Gō'ēl) as depicted by Holy One of Israel in Deutero-Isaiah and the thematic commonalties of the passages involved. The earthly office of Gō'ēl exhibits a radial structure of four models that entail several senses of the concept the people of Israel associated with the office of redeemer, these are: 1) Pentateuchal Model; 2) Royal Model; 3) Marital Model; and 4) Avenger Model. Pertinent to the discussion is the way in which Isaiah extends the title by pairing Redeemer with the Holy One of Israel six times in chapters 41, 43, 47, 48, 49, and 54 suggesting Gō'ēl fulfills a sacred office associated with restoring the broken covenant relationship between Yahweh and Israel. A fifth structural component to the sacred office, the Holiness Model, is proposed which suggests a five model structure for the category of Redeemer.

Keywords: Redeemer, Holy One of Israel, Radical category, Isaiah

Trefwoorde: Verlosser, Heilge van Israel, Radikale kategorieë, Jesaja

1. INTRODUCTION

From a cognitive semantic perspective1, the writer Isaiah combines an earthly office and sacred office in the role of the divine kinsman-redeemer (Gō'ēl). Yahweh assumes the earthly office as Redeemer of his covenant people in a concrete sense of physically delivering Israel from Babylonian captivity. Isaiah presents this liberation as a new exodus2 and uses the concept of Gō'ēl with its various familial implications to frame divine promises for a post-exilic experience. In addition, Isaiah extends the title by pairing Gō'ēl with the Holy One of Israel six times in Isaiah 41:14, 43:14, 47:4, 48:17, 49:7, and 54:5 suggesting Gō'ēl fulfills a sacred office with spiritual connotations of deliverance associated with restoring the broken covenant relationship between Yahweh and his people (see Table 1). This paper explores the radial category3 nature of Redeemer (Gō'ēl) as depicted by Holy One of Israel and the thematic commonalties of the passages involved.

The notion of radial categories refers to one prototypical member that is central to category meaning with other sub-members linked to the center by various types of connections. A radial category is a type of polysemy network in which a concept exhibits multiple meanings. Thus, a radial category is a cluster model in which there are several senses of a concept such as Redeemer and each of the senses are part of the same complicated concept. There is a central case in which all the defining criteria are satisfied, and various senses may be viewed as variant models that require only a partial link to the central case.

The classic example of a radial category is Mother (Lakoff 1997:74-84, 91). The central (prototypical) American model of mother includes a female who: 1) supplies half the genetic makeup, 2) gives birth, 3) nurtures the child, 4) is one generation older than child, 5) is married to the child's father, 6) and is the child's legal guardian. The radial structure of mother also contains variant models such as the: Genetic model which may include birth mother, natural mother, unwed mother, and biological mother; Genealogical model which may include birth mother, natural mother, biological mother, adoptive mother, unwed mother; Marital model which may include adoptive mother and step mother; and Nurturance model which may include foster mother, step mother, natural mother, surrogate mother. Examples of peripheral members may be: 1) a birth mother who does not nurture the child but gives birth; and 2) a stepmother who does not give birth to the child or (in some cases) nurture the child, but is married to the father. The central member, then, of a radial category is defined by a cluster model: a group of converging properties.

Discussing the meaning implications for the title, Redeemer, Holy One of Israel, in terms of the cognitive linguistic framework of radial categories offers the opportunity to gain a fuller understanding of the conceptual title and its use within the Isaiah text. Exum and Clines (1993) support this kind of multidisciplinary methodology in their arguments for a new literary criticism of biblical texts. The idea being new disciplinary approaches applied to familiar biblical texts yield wider and deeper understanding as well as evaluation of the texts as literary works. Alas, New Literary Criticism goes beyond meaning of the text to value of the text. In the case of Redeemer, Holy One of Israel, the literary value of the title is found in the accompanying themes. Considering a cluster model of Gō'ēl broadens our knowledge and value of the radial character of Redeemer as a culturally defined concept which has a conventionalized central model with variations that cannot be predicted by general rules. Redeemer, Holy One of Israel is defined by a cluster model or a group of converging properties which is communicated through the pragmatic impact of the data.4

Yahweh as Holy Redeemer of Israel is unique in that all Other5 pales in comparison to his holiness. Exodus 15:11 and 1 Samuel 2:2 declare the holiness of God cannot be matched. The people of Beth Shemesh wonder aloud, 'Who is able to stand before Yahweh, this holy God?' Isaiah answers that it is those whom the divine Redeemer has chosen to share in his holiness which are his chosen people, Israel. Isaiah alone uses the descriptive phrase, Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel, in reference to Yahweh.6 Delitzsch (1892:182) commented that the phrase Holy One of Israel forms an essential part of 'Isaiah's peculiar prophetic signature.' Redeemer as the first term in this compound title of Yahweh is utilized in the second part of Isaiah's prophecy whereas the second title, Holy One of Israel, somewhat characterizes the book as a whole.7 The focus of Isaiah on holiness and righteous judgment are endemic themes which begin from the start and continue throughout his prophecies. The theme of redemption becomes prominent in Deutero-Isaiah coupled with qadös although the prophet has prepared the reader for this theme as early as 35:9 when Israel is referred to as the redeemed and in verse 10 with the parallel verb padá, and the ransomed.8

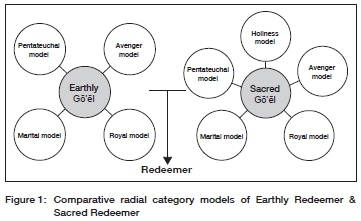

This paper suggests that the earthly office of Gō'ēl exhibits four models in the radial structure of redeemer, these are: 1) Pentateuchal Model; 2) Royal Model; 3) Marital Model; and 4) Avenger Model. These four models entail several senses of the concept the people of Israel associated with the office of redeemer and fulfilled in an earthly sense by an Israelite. The characteristics of each model will be considered in the following discussion in relation to how the components are reflected in the sacred office of Gō'ēl as executed by Yahweh (see Fig. 1). Yahweh as Redeemer is a conceptual metaphor used by Isaiah to describe the role of Yahweh in Israel's redemption. Gitay (1997) recognizes the value of Isaiah's use of metaphors for both the writer and the audience. It seems Isaiah was a forerunner of cognitive semantics with his constant use of vivid imagery of relationships through metaphoric language.

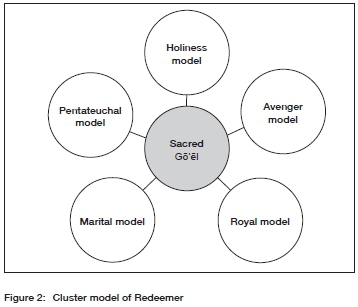

An additional structural component of sacred Gō'ēl, the Holiness Model, will be proposed to suggest a five model structure for the overall category of Redeemer (see Fig. 2).

The title, Redeemer, Holy One of Israel, is set within thematic contexts which Isaiah has framed to communicate his message. Indeed, a number of scholars propose a macro-literary structure for the whole book of Isaiah to be that of thematic constructs. Gileadi (1994; 2012) suggests seven thematic repetition patterns are present and organized through a chiastic structure of the book. Each thematic category uses literary features to provide category uniqueness. These literary devices include the use of common motifs associated in the first thematic category; chiasm and parallelism in the second thematic category; internal alternating patterns of chaos and creation in the third thematic category; generic features using prophetic oracles against depraved people in the fourth thematic category; dominant recurring concepts of suffering and salvation in the fifth thematic category; parallel or anthithetical expressions in sixth thematic category; and decisive contrasting portrayals of Israel and her enemies in the seventh thematic category.

O'Connell (2009) believes the overall literary form of Isaiah rhetorical strategy in Isaiah seems to be governed by the genre of covenant disagreement but this in no way ignores the variety of speech forms Isaiah uses that are not commonly associated with prophetic covenant disputations (woe oracles, judgment speeches, salvation oracles, invocation hymn, etc.).

The literary forms of second Isaiah are framed within the norms for prophetic speech with the predominate forms of rebuke and oracle of promise (McKenzie 1968). Elements of prophetic literature are contained in second Isaiah as well including narratives comprised of vision and hearing, tender speech of comfort and promise, stark rebukes and admonitions, and taunt songs. The title, Redeemer, Holy One of Israel, is one way of encompassing various themes into complimentary relationships.

Investigating the radial category nature of redeemer requires considering salient category exemplars which can be gleaned from surrounding themes in the text. Thus the organizational pattern of this paper highlights four primary themes in which the complicated conceptual senses of Redeemer are revealed. Turning now to themes in chapters 41, 43, 47, 48, 49, and 54 of Deutero-Isaiah, the first to be considered is, Yahweh the creator God rules over other.

2. THEME: YAHWEH THE CREATOR GOD RULES OVER OTHER

Isaiah 54:5 declares the God of the whole earth is holy, qadös. Central to the meaning of qadös is the notion of purity and this purity sets one apart from created Other. The image is one of Creator God high and lifted up above his created, incomparable in his power and purity, and with the ability to create and sanctify whatever is his pleasure. He is the quintessential Redeemer separate and transcendent from lowly man because of his divine holiness. This sacred divine otherness separates the Creator from created Other.

The title, Gō'ēl, Qadös Yisra' êl, signals divine responsibility and authority in the relationship between Yahweh and his people. Creator God is both holy and separate yet permanently bonded to Israel. By placing the terms in construct, the author signals a paradox in which Yahweh, the Separate One, belongs to Israel. Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel as a unified divine title suggests qualifying the relationship between the divine Redeemer and Israel with different possessive meanings: 1) Israel is the property of Gō'ēl, Qadös Yisra' êl; 2) Gō'ēl, Qadös Yisra' êl is ruler over Israel; and 3) Israel is dependent on Gō'ēl, Qadös Yisra' êl.10 It is the first of these possessive meanings which reflects the theme here. Yes, Yahweh belongs to Israel; nonetheless, Israel belongs to her Redeemer. The Holy Redeemer retains ownership of his covenant people as his property which is perhaps a reflection of his sovereignty and a trait of his divine otherness.

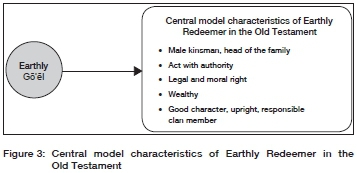

The notion of authority is a central feature of an earthly Gō'ēl. The male kinsman serving as the head of the kin group possessed legal and moral authority by virtue of his generational position and social position of greater wealth than most members of the clan. In general a kinsman-redeemer exhibited good character and acted in a responsible manner toward his duties as family patron (see Fig. 3). Thus authority and elevated social position as patron was tempered by duty and responsible active leadership.

2.1 Establishes divine authority as redeemer

Isaiah wisely establishes the authority of the Sacred Redeemer as Creator God who, as the Holy One of Israel, rules with absolute authority over the created world. This holy Gō'ēl is the one who laid the foundation of the earth (Isa. 48:13), commands nature (Isa. 41:18-19; 43:20; 49:11), and created man (Isa. 41:4; 43:1; 54:5). The Maker (Isa. 54:5) of Israel has cosmic authority behind his duty to Israel as her husband (Isa. 54:5). The Creator pledges his commitment to his people as a husband does to his wife. No one is able to challenge the divine Redeemer for no Other exists with higher authority either in direct relationship with Israel or in the cosmic realm. The will and intentions of Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel will be done because, as with the first and with the last (Isa. 41:4), Yahweh has and will continue to direct history. He is Israel's kinsman-redeemer over the course of history and has not only formed and made (Isa. 43:7) Israel but has always directed events and rulers in her redemptive journey.11 Isaiah 48:12 also depicts Creator God as the One who is the first and who is the last. He is the one and only God commanding the universe and here calls Israel by name.

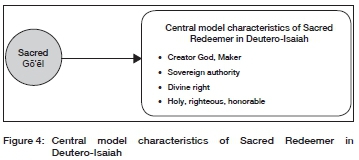

In Isaiah 43:11, 15, Isaiah establishes Yahweh as the only possible savior (mösha'a) for Israel with two fronted first person pronouns in their long form in verse 11 accentuating exactly who is God (Yahweh) and his divine authority as Israel's covenant savior.12 However, verse 15 is frontedwith a shorter form of the pronoun, I, in a longer descriptive title, I am Yahweh, your Holy One. Yahweh is God and He is the Creator; He is the Holy Redeemer who belongs to his covenant people. By establishing the cosmological place of God in relation to Israel and the created world, Isaiah delineates divine right and authority of a sacred office to act as Holy Redeemer for Israel and the precedence of an earthly office for delivering Israel from her enemies (see Fig. 4). The Isaiah text is a confluence of two great themes, God as Holy Redeemer and God as Creator which Isaiah uses as a theological support for the redemption of Israel (Stuhlmueller 1970:101).

3. THEME: YAHWEH IN UNIQUE RELATIONSHIP WITH COVENANT PEOPLE

Israel as a people has been singled out of all the nations and chosen by Creator God to be his covenant people i.e. people of The Promise. Isaiah 41:8-9 reaffirms Israel as those who have been chosen by Yahweh to share in his holiness and let this holy nature be a witness to other nations.13 The term chosen has inherent theological meaning reflecting some type of eternal significance. The Holy Redeemer chooses Israel as his own with a number of concepts depicting this ownership relationship in the texts under discussion.14 This choice implies he will honor their rights under the agreed upon terms of the covenant and fulfill his role as Redeemer by securing their release from Babylon. Even further, chosen implies it is the sacred duty of Yahweh to not cast15 Israel aside but as Holy Gō'ēl redeem her in holiness as an eternal witness to his glory. The disapproval of sin does not mean God is able to reject Israel totally by leaving her in foreign bondage, casting her aside as his chosen people, or condemning her apostasy with eternal torment because any of these actions would break the covenant of Leviticus 26:44.

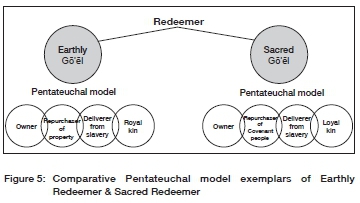

The Deutero-Isaiah text surrounding Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel describes the covenant relationship between Yahweh and Israel in a way that reflects the pentateuchal model of earthly and sacred Gō'ēl. The earthly pentateuchal model allowed a loyal kin member to repurchase property sold in time of need or redeem property dedicated to the Lord,16 free an Israelite slave sold in time of impoverishment,17 and receive atonement money by offenders on behalf of the family.18 These elements correspond with the exemplars of the Sacred Redeemer albeit with the repurchaser motif narrowed in the sacred model to specifically refer to Israel as the property under redemption. Thus Yahweh displays his loyalty by repurchasing and delivering Israel from slavery under the Babylonians with the promise, I give Egypt as your ransom, Ethiopia and Seba in exchange for you19(see Fig. 5).

In addition, these passages reveal the motivation and purpose behind the covenant. Yahweh uses the covenant with his chosen people as a tool of light to Gentile nations. In a greater universal truth, the covenant with Israel is only an example of what God intends for all people. Universally God desires all people, regardless of ethnicity or nationality, be people of his name and worshippers of his holiness.20

3.1 Establishes divine redemptive relationship with covenant people

Isaiah describes the redemptive relationship of the Holy Redeemer with Israel through earthly relational imagery. The covenant people have been called by my name,21meaning the name of the Lord, placing them in the inner circle of Yahweh's immediate kin.22 As such, the name of the Lord implied by the text is Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel. To be redeemed both physically and spiritually, Israel needs a legitimate redeemer with legally binding credentials. This qualification is met under the conditions of authority by the Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel who created and shares his name with Israel.23 Israel then is not only people of The Promise but also people of The Name. To share the name of Yahweh is to be a servant ('ebed) of God with the concept of servant itself displaying different senses within the Isaiah text.

The Holy Redeemer calls Israel by his holy name to be his servant ( ebed). Indicative of Old Testament times, a worshipper of any god was considered a servant and one devoted in ritual acts required to honor their deity. Israel as a servant of Yahweh was obliged by duty to worship and honor the Lord in word and deed.24 There are several nuances of meaning associated with ebed and patron. A servant is not only dependent on his lord but also subjugated to his authority in degrees up to total capitulation including the expectation of loyalty Ringgren (1999:376-390).25 However, in the Old Testament, the patron was bound to protect his covenant servants and provide for their welfare.26 The position of servant included certain rights and the exchange of trust between servant and lord (Kaiser 1980:639). Israel was then to serve her Creator by covenant faithfulness, and Yahweh upheld his covenant responsibility by acting as Israel's Redeemer, her loyal patron.

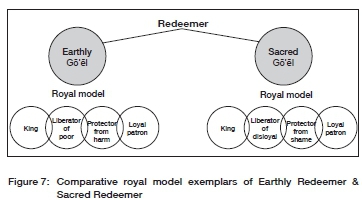

Isaiah associates the divine Gō'ēl with a royal office (Isa. 41:21; 43:15) and places the redeemed as servants who are subjects of the King. This is an example of socio-political dependence by the servant Israel on her Holy King. An ideal prototypical king would go to great lengths to protect his people and do all within his power to provide for their welfare27 (see Fig. 7). Thus in the covenant relationship, the Holy Redeemer not only rules over Israel but in addition, Israel is dependent on her Sovereign Ruler for protection.

The regal authority of the Holy Redeemer is unmatched by any other earthly kingdom; thus, he will send to Babylon and break down all the bars (Isa. 43:14) and return those called by The Name to his kingdom of promise. This is quite a contrast to the actions of God in Judges 2:20-21; 3:7-8; 10:13 where Yahweh is angry with Israel because she has not served him and the Lord withholds his political help from Israel. In these passages Israel was required to do away with idols and again reaffirm loyalty to Yahweh by complete service to him. The voice of Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel is quite different. Yahweh acknowledges Israel's disloyalty but offers liberation despite the fact she has been a corrupt servant. Yahweh is in a covenant relationship with his people and extends the relationship even further by taking on the role of redeemer even though Israel has ignored The Promise and brought shame to The Name by worshipping other gods. With like manner of an earthly king, the divine King promises to liberate the lowly subjects of his realm despite their disloyalty.

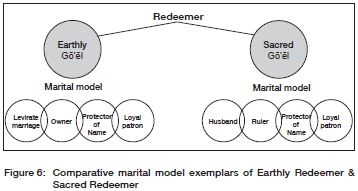

This may also be a general representation of servant in which a covenantal relationship is depicted between a weaker member and a stronger member in a covenant (North 1980:292). As a servant to the master, whether it be a people to their king or, as in the case of Isa. 54:5, a wife to her husband, the patron remains in a superior position to the subservient member of the pledge. In Rabbinic law, the husband was to rule from a position of authority over his wife.28 The Maker of Israel is also her husband, ba'al, who both owns and rules over that which is in his possession. Israel acknowledges the absolute headship of her divine Husband by entering a contractual agreement with Yahweh29 (see Fig. 6). The Lord declares that his steadfast love or covenant loyalty is forever with his people and their offspring (Isa. 54:10). The God of the whole earth who happens to be Israel's husband rules over her with compassion (v. 7-8,10).

3.2 Establishes divine redemptive promises with covenant people

One of the most powerful promises in the covenant relationship is scripted in Isa. 49:3, 'And he said to me, "You are my servant, Israel, in whom I will be glorified.'"30Israel has been disloyal to her honored place as one chosen to be the servant of the Creator. Yet, to be called my servant, Israel as in Isa. 41:8; 43:10; 49:3 is to be recognized with an honorific title by the Holy Redeemer. Glory is associated with people of high status such as a king who by their very office command authority and honor. Yahweh is viewed in the splendor of his holiness and will not share this glory with any Other (Isa. 48:11) except his chosen servant. The promise of God manifesting his glory in Israel encompasses a great many residual promises in the text.

The prototypical servant will behave toward his lord in a way befitting the obligatory homage; nonetheless, Israel has sinned by dishonoring Yahweh through swearing by the name of the Lord, and confessing the God of Israel, but not in truth or right (Isa. 48:1). The reputation of Israel is not only at stake but also her King and Lord who happen to be her kinsman-redeemer. As sacred Gō'ēl, Yahweh assumes a kingly role which includes the title of Protector from shame that corresponds with the earthly royal model of king, the Protector from physical harm. Both the earthly and sacred royal models of Redeemer include similar exemplars such as Protector, Liberator and Loyal Patron (see Fig. 7).

The redemptive promises are as much for Yahweh as they are for his people. It is for his own sake he redeems Israel, and Isa. 48:11 marks the phrase for my own sake for emphasis by repeating it (Isa. 48:11). A redeemer cannot let his servant be shamed because the shame continues forward until resting on the redeemer himself. The notion of glory carries with it the idea of reputation which has much significance for one at the top of a sacred and/or earthly hierarchy. Because He will not allow his name to be profaned (Isa. 48:11), Yahweh will not allow his people to be put to shame (Isa. 49:23). The name of God profaned is antithetical to his name as the Holy One of Israel. He is holy and his holiness cannot be violated in the sense of being compromised else wise the reputation of Yahweh as Creator God among the nations would be diminished. The glory and holiness of Yahweh would lose divine authority among man.

The Holy One of Israel must demand holiness from his servant which can only be met through the work of mercy and redemption He alone can provide as Sacred Redeemer. He will restrain his punishment because of his name's sake and not dishonor his name by breaking the covenant. Further, he must redeem Israel from her earthly and spiritual plight and restore her as a nation and his people. It is his divine holiness that implores Yahweh to act as sacred Gō'ēl and redeem Israel. He is the King of glory31 deserving of reverence because of his position as Creator God and his pure holy character. It is his holiness that compels Yahweh to compassionate action as Redeemer.32

4. THEME: YAHWEH THE JUDGE OF ENEMY NATIONS

The repeated use in Deutero-Isaiah of Redeemer, Holy One of Israel announces the certainty of punishment for Babylon just as it reinforces the promise of deliverance for Israel. Acting as the Gō'ēl, Qadös Yisra' êl does give impetus to the divine enactment of vengeance referred to in Isaiah 47:3 and the accusatory tone found in Isaiah 41, 43, 48, 49, and 54. The judgment of Yahweh will fall on enemy kings and princes so that they will prostrate themselves before Israel and her God (Isa. 49:7) and with their faces to the ground they shall bow down to the people of The Name (Isa. 49:23). Why? Because Yahweh reassures his people that I am the Lord, your Savior, and your Redeemer, the Mighty One of Jacob (Isa. 49:26) and as such I will contend with those who contend with you (Isa. 49:25) and those who strive against you will be as nothing (Isa. 41:11). It is to the notion of contend (strife, oppose) we now turn our attention.

According to Limburg, contend (rib) is used in three separate Old Testament settings: 1) the court setting at the gate; 2) the formal religious setting; and 3) the setting of international relationships.33 Rib in the context of Isa. 49:25 refers to the cultic setting in which Yahweh as the subject of the verb serves as the defender for his covenant people. The Holy Redeemer has the customary legal right to act as an advocate for Israel and oppose those who oppose her. Even though it is Israel who has broken the covenant, Yahweh issues an accusatory consequence against Israel's oppressors in verse 25-26 whom he allowed to vanquish his chosen people in the first place (Isa. 47:6). The divine declaration from Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel is those who strive (rib) against you will be as nothing and will perish (Isa. 41:11).34Our Redeemer, the personal Holy One of Israel, promises vengeance in Isa. 47:3-4.

It is not only the living captives that cry out for deliverance, but those who lost their lives at the hands of the enemy nations. A person's blood will cry from the ground as long as it remains uncovered35 in place of the testimony by a witness to the crime.36 Isaiah 47:3 warns Babylon that your shame will be seen; in other words, the disgrace of your actions are not covered over but are publicly known by all. Hence, those trampled become the evidence that condemns and ushers in the promise, I will take vengeance. These are most chilling comments, and, in today's vernacular could be literally taken as, 'Be afraid. Be very, very afraid.' Whereas Israel is promised to share in Yahweh's glory and honor, Babylon receives an antithetical promise of dishonor and shame that are a product of divine judgment by an avenging God.

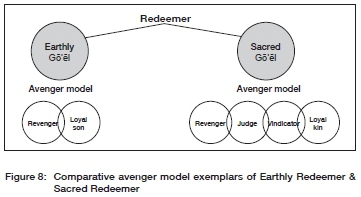

4.1 Establishes divine redemptive role as avenger

While the Holy Redeemer is a friendly Gō'ēl to his chosen people, on the other hand, Yahweh may be viewed as an unfriendly Gō'ēl toward enemy nations (see Fig. 8). A unique point in the pattern of Gō'ēl in Deutero-Isaiah is the Lord as an avenger taking revenge on Israel's murderous captors (Isa. 47:3).37 The earthly office of Gō'ēl maintained a role of blood avenger (Gō'ēl haddam) in which the kinsman-redeemer had the legal authority to determine guilt or innocence in the death of a clan member.38 It did not matter if a family member had been killed accidentally or with premeditated thought because the appropriate restitution exacted by a kinsman-redeemer was capital punishment. Someone guilty of taking the life of another would be tracked down and killed by the loyal kinsman-redeemer if the guilty party fled instead of facing his accusers. It was the responsibility of the community to provide protection for the offender in places of refuge for accidental deaths.39 In any case, a life for a life was the norm.40 As with most customary corporal roles, the mere social office of a Gō'ēl was a deterrent to murder since the offender could expect equal retribution.

While generally the focus of divine wrath in the Old Testament is to highlight divine mercy, Isaiah 47 is the exception.41 Chapter 47 is addressed to the Babylonians and thematically mocks their so called victory over Israel and sets forth in what way the Holy Avenger will judge their wickedness. Divine judgment will be as severe as the enemy inflicted on Israel and according to the righteous character of Yahweh as Israel's loyal kin; hence the promise, I will take vengeance, and I will spare no man (Isa. 47:3).42 The Holy Redeemer must act with vengeance against Babylon in order for the theme of mercy toward his chosen people to have complete meaning in chapters 41, 43, 48, 49 and 54. Restoration of the vanquished requires vindication, and vindication demands inflicting punishment on those guilty by repaying their behavior in kind (Isa. 54:17).

Thematic tendencies for the concept of Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel seem to support a twofold understanding of the term righteous. One aspect of meaning for sedeq is the positive action of deliverance and salvific purpose which will be discussed later and secondly, a punitive judgment issued by the divine as Holy Avenger.43 The enemy nations are an abomination in their idolatry (Isa. 41:24) and secure in their wickedness (Isa. 47:10). This security carries with it a careless confidence so much so that the Babylonians are deceived into believing they can crush the people of Yahweh with no reprisal for their cruelty.

Isaiah 47:6 speaks of the enemy captors as showing Israel no mercy (rahámim). Rahámim brings together the verb, raham meaning 'to have compassion' and the noun, rahama meaning 'womb'. The verb, raham, includes a connotation of man's intuitive sense of mercy toward fellow human beings; and the noun, rahama, ties the physical aspect of compassion to the experience of deep emotional expression. Thus it is this natural sense of feeling a deep compassion (rahámim) for the helpless that Babylon does not exhibit (Coppes 1980:841). What has been taken from Israel will now be restored through divine vengeance by the Sacred Redeemer (see Fig. 8). By an act of justified vengeance, Yahweh maintains his place of supreme honor and restores the loss of personal honor Israel suffered (Pedersen 1991:389).

The sin of man whether it be a nation or single individual is without fail remembered and dealt with accordingly by God.44 It is therefore no surprise the Holy Avenger intends to vindicate his people. The promise is that he will perform his purpose on Babylon (Isa. 47:14). Instead of a covenant of peace, Yahweh guarantees a covenant of strife with Babylon (Isa. 48:22). This stands in contrast to the Holy Redeemer who declares to Israel with emphatic voice, I, I am He who blots out your transgressions for my own sake, and I will not remember your sins (Isa. 43:25). The Babylonians however are not so fortunate because the Holy Redeemer does remember their profanity and the Holy Avenger promises in no uncertain terms, there is no one to save you (Isa. 47:15).

5. THEME: YAHWEH THE CONFIDENCE OF HIS COVENANT PEOPLE

The office of kinsman-redeemer in a socio-cultural sense is a social position that exists as a tribal means of protecting clan members. It is a social confidence mechanism against the perils of life that are either self inflicted or experienced through no fault of the individual. A member of a family would anticipate someone of status from the kin group to come to their aid as kinsman-redeemer. Pedersen suggests shame occurs when assistance one confidently expects does not happen (Pedersen 1980:242). In this case, Israel is in the helpless position of needing a redeemer, yet, because of her untenable position of political defeat, she publicly has lost honor i.e. divine prosperity and quite openly shamed. The fault lies squarely on Israel and not her divine kinsman. The source of Israel's shame is her spiritual weakness that caused the shameful worship of other gods in the place of Yahweh. The family edict had been given on Mt. Sinai and family law discussed, still Israel rejected her familial responsibility and duty which resulted in public humiliation.

The redemptive promises made by the Holy Redeemer are interwoven within the framework of Fear not charges in Isa. 41:10, 13-14; 43:1, 5; 54:4, 14.45 If Creator God is your Gō'ēl, there is nothing to fear even though the circumstances seem otherwise. Isaiah lists a host of probable apprehensions and counters with statements meant to boost trust, assurance, and hope. Israel is not to be dismayed because Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel is her God (Isa. 41:10). The Holy Redeemer pledges to reverse the natural order of condemnation by bringing shame on Israel's enemies and restoring honor to Israel in place of her earned disgrace.

The chosen people need reaffirmation the Holy Redeemer has not renounced his people and the emphatic statement, Fear Not, for I am with you, (Isa. 41:10; 43:5), is meant to reassure Israel their breach of covenant does not mean permanent abandonment. Of the various senses of meaning encompassed by 'al tira', Fear not, the sheer emotion of fear seems most probable with a meaning used as a command for confidence. The Holy Redeemer makes his redemptive presence clear, I am with you.46The divine kinsman-redeemer has come and there is no need to fear earthly or sacred desolation.

In the Isaiah 41:10 passage, be not dismayed, for I am your God is a parallel formulaic command to Fear not which exhorts Israel to not look about in fear.47 And why should they glance to and fro in terror? Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel reminds his people that He is their God, the one true 'Ël that has power to strengthen, help, and uphold a vanquished people. Once again Isaiah uses a common thematic phrase to qualify the relationship between Yahweh and Israel: I am your God.48The phrase evokes the imagery of a victorious historical past in which the God of Israel delivered his people from the tyranny of others. The three verbs following I am your God represent general truths concerning Yahweh and his chosen people. Translating the three verbs as I will strengthen, I will help, I will uphold does not quite capture the significance of Yahweh's on-going covenantal relationship with Israel.49 A more accurate rendering is: I strengthen you, moreover I help you, moreover I uphold you.50

Isaiah 47, 48, and 49 do not contain Fear not commands but do have other hortatory statements. In Isa. 47, the chapter begins with a series of harsh commands as pronouncements of judgment on Israel's enemy captors. While Israel is encouraged not to fear their present circumstance, the proud victors are boldly told their seeming victory over Israel has condemned them. While the chosen people are not to fear shame, Creator God guarantees shame will come to Babylon (Isa. 47:3). Indeed, the Lord commands Israel to leave exile with joy instead of fear and declare, The Lord has redeemed his servant Jacob! (Isa. 48:20). Isaiah 49:18 strongly encourages Israel to Lift up your eyes and see her enemies brought down and humbled before her. Isaiah 47:12-13 issues rhetorical commands to Babylon to Stand fast in their heathenism and let their sorcery save them from righteous judgment. It is as if the writer is feeding the false security and earthly pride of enemy.

5.1 Establishes divine righteousness and vindication

Yahweh establishes confidence in his people through forcefully admonishing them to relinquish fear and accept his provision of help. This empowerment is signified by God's righteous hand. There is no need to fear before the manifestation of God's power. Yahweh clearly reaffirms his loyalty to Israel and, as Holy Redeemer, it is the right hand of his righteousness that wields the power of victory over earthly enemies and spiritual darkness (Isa. 41:10; 54:14). Sedeq is a key term in understanding the nature of Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel.

Righteousness is a significant concept in Hebrew world view. To be righteous is to behave in a right manner. This outward action is a manifestation of a man's inner condition. What is noteworthy is that the nature of the Hebrew inner man is predicated on maintaining the covenant. Thus the righteous man exposes his inner purity by outwardly following the precepts of the covenant. To be righteous is to share in the fellowship of divine holiness through covenantal practice.51 According to Old Testament law, to be righteous was to be innocent (Stigers 1980:753). It is the righteous intervention by God which makes Israel innocent (righteous) of her shameful behavior. Yahweh judges both Israel and her enemies to maintain the covenant through divine righteous action.

In one sense, God acts as a friendly Gō'ēl who, because of his holiness and righteousness, will not remember Israel's sins (Isa. 43:25), will defer anger and restrain his punishment (Isa. 48:9). God displays his righteous character when he delivers his chosen people from the dishonor of exile and the spiritual act of profaning The Name. To be Sedeq, one must be obedient to the covenantal law and conform oneself to the holy nature of Yahweh; and in this regard, Israel has failed miserably. Yet, the Holy Redeemer is true to his holy, sacred character and fulfills his earthly covenant duty through pleading Israel's cause among the nations (Isa. 43:9; 49:7, 22-23). Yahweh both judges and vindicates in a way that defends those whom He makes righteous (chosen people) among the wicked (other nations).

As a righteous Redeemer, God steps into the role of deliverer. Gō'ēl, Qadös Yisra' êl delivers Israel from captivity by enemy nations and being captive by the grip of sin. Redemption is the subject of the oracle of salvation in Isaiah 43, and verse 13 suggests both a physical and spiritual salvation.52 Only Creator God has the sheer power and spiritual authority to deliver Israel from earthly and sacred bondage. This display of righteous honor is meant as a light to the nations. The chosen people are Yahweh's servant depicted in the Servant Song of Isaiah 49:1-6 and commissioned as a spiritual light unto the world. Deliverance is accompanied by salvation and infers judgment which in turn implies an act of righteous justice. The Holy Redeemer intends his role as savior of Israel be salvation that reaches to the end of the earth (Isa. 49:6). Thus by delivering Israel, the Holy Maker manifests the very essence of what it means to be the Holy Redeemer (see Fig. 9).

Integrated within the conceptual network of righteousness, honor, blessing, and holiness is the notion of shame. Isaiah 54:4 uses three parallel verbs for the concept of shame: "Fear not, for you will not be ashamed (bos); be not confounded (kalam), for you will not be put to shame (hapêr)...." Bos is the salient term with kalam53 and hapêr54 used in parallel as amplification words. Israel is being admonished not to fear because the Lord promises his chosen people will not continue to be publicly disgraced (bos), publicly humiliated (kalam), nor publicly embarrassed (hapêr).55 One maintains their standing of earthly and sacred blessing with obedient behavior to the covenant.

Defeat brought devastating humility which diminished the importance of Israel in the eyes of other nations coupled with lost command of respect she enjoyed while in covenant obedience with Yahweh. However the divine promise rings out: you will forget the shame of your youth, and the reproach of your widowhood you will remember no more (Isa. 54:4). The Holy Redeemer declares that Israel's disgrace is temporary. And further, the servant Israel will not continue to bring shame on her Maker, Lord, husband, Redeemer, who is called the God of the whole earth.56In ancient Hebrew world view, the opposite of shame was honor; and honor was an acknowledgement of higher status by others who were dependent on the honoree. The weaker member of a relationship had the power to increase the honor of their patron by recognizing patron support. The weaker member also increased the honor of the patron by surrendering volition which in the case of Israel was conforming to the covenant. Thus by removing shame from Israel, Creator God removed shame from the covenantal family line and Israel's husband once again assumed his rightful place of honor as the Holy One of Israel who is your Redeemer.

6. CONCLUSION

The title, Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel, is employed by Isaiah to communicate divine agency. Williamson (2001:34) suggests "the title 'Holy One of Israel' came to be applied by a natural extension to Yahweh" and if so, then it is also a natural addition to the name of divine Redeemer. The person of Yahweh and his intentions are much more than the earthly office of Gō'ēl could encompass; thus, Isaiah was compelled to extend the category meaning of Gō'ēl in such a way as to include components which reflected divine character and covenantal expectations.

The qualifying evidence for Holy One of Israel as attached to Redeemer dismisses the argument that Holy One of Israel is simply a variant of the God of Israel.57The conceptual structure of Redeemer becomes wider and more complex when Holy One of Israel is added to the divine title. The earthly office of Gō'ēl is still an intended role for Yahweh but with the theme of holiness brought to the forefront, Isaiah underscores the spiritual condition of Israel. In Israel's deliverance from Babylon, the people must recognize their relationship with Yahweh be entered with compliance to his holy nature. And it is this holy nature motivating the actions of God as Redeemer.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Coppes, L. 1980. רחם. In: R. Harris, G. Archer, & B. Waltke (eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Vol 2 (Chicago, IL:Moody Press), pp. 841-843. [ Links ]

Culver, R. 1980. ריב. In: R. Harris, G. Archer, & B. Waltke (eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Vol 2 (Chicago, IL:Moody Press), pp. 845-846. [ Links ]

Delitzsch, F. 1892. Biblical commentary on the prophecies of Isaiah. Edinburgh:T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Harner, P. 1969. The Salvation oracle in second Isaiah. Journal of Biblical Literature 88:418-434. [ Links ]

Henne, D. 1999. Translator's notes on Isaiah: Appendix 1: Some key words in the books of the Old Testament prophets, unpublished manuscript. [ Links ]

Johnson, A.R. 1960. Hebrew conceptions of kingship. In: S. Hooke (ed.), Myth, ritual, and kingship. (Oxford:Oxford University Press), pp. 204-235. [ Links ]

Kaiser, W. 1980. עבד. In: R. Harris, G. Archer, & B. Waltke (eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Vol 2 (Chicago, IL:Moody Press), pp. 639-641. [ Links ]

Kearney, M. 1984. World View. Novato:Chandler and Sharp. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G. 1997. Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago:University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Limburg, J. 1969. The root ריב and the prophetic lawsuit speeches. Journal of Biblical Literature 88: 291-305. [ Links ]

Lipinski, L. 1999. Dp]. In: G. Botterweck, H. Ringgren, & H. Fabry (eds.), Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Vol 10 (Grand Rapids, MI:Eerdmans), pp. 1-9. [ Links ]

Morris, L. 1955. The Biblical use of the term 'blood.' Journal of Theological Studies 6: 77-82. [ Links ]

North, C. 1980. The Servant of the Lord (עבד יהוה). In: G. Buttrich (ed.), Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible. Vol 4 (New York:Abingdon), pp. 292-294. [ Links ]

Oswalt, J. 1998. The Book of Isaiah: Chapters 1-39. Grand Rapids:Eerdmans. New International Commentary of the Old Testament 1. [ Links ]

Pedersen, J. 1991. Israel: Its life and culture. Vol 1, Atlanta:Scholars. [ Links ]

Redfield, R. 1953. The Primitive world and its transformations. NY:Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Ringgren, H. 1999. עבד In: G. Botterweck, H. Ringgren, & H. Fabry (eds.), Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Vol 10 (Grand Rapids, MI:Eerdmans), pp. 376-390. [ Links ]

Smick, E. 1980. נקם. In: R. Harris, G. Archer, & B. Waltke (eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Vol 2 (Chicago, IL:Moody Press), pp. 598-599. [ Links ]

Stigers, H. 1980. צדק In: R. Harris, G. Archer, & B. Waltke (eds.), Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Vol 2 (Chicago, IL:Moody Press), pp. 752-755. [ Links ]

Stuhlmueller, C. 1970. Creative redemption in Deutero-Isaiah. Rome:Pontifical Institute Press. [ Links ]

van Selms, A. 1982. The expression 'The Holy One of Israel.' In: W. Delsman & J. van der Ploeg (eds.), Von Kanaan bis Kerala (Kevelaer:Butzon & Bercker), pp. 257-69. [ Links ]

Watts, J. 1987. Isaiah 34-66. Waco, TX:Word Books. Word Biblical Commentary 25. [ Links ]

Weinfeld, M. 1995. כבוד. In: G. Botterweck, H. Ringgren, & H. Fabry (eds.), Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Vol 7 (Grand Rapids, MI:Eerdmans), pp. 22-39. [ Links ]

Whitley, C. 1972. Deutero-Isaiah's interpretation of sedeq. Vetus Testamentum 22: 469-75. [ Links ]

Williamson, H. 2001. Isaiah and the Holy One of Israel. In: A. Rapoport-Albert & G. Greenberg (eds.), Biblical Hebrew, Biblical Texts: Essays in Memory of Michael P. Weitzman (London:Sheffield), pp. 22-38. [ Links ]

Wolff, H. 1996. Anthropology of the Old Testament. Mifflintown:Siglaer. [ Links ]

Young, E. 2000. The Book of Isaiah. Vol 3. Grand Rapids:Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Zimmerli, W. 1982. I am Yahweh, Your God, tr. D. Stott. Richmond:John Knox. [ Links ]

1 "Cognitive semantics is the study of meaning in the embodied human mind" (Brandt 2005:1578). It is the study of the relationship between experience, cognition, and language. Cognitive semantics investigates how knowledge is represented and how meaning is constructed as a mental concept. Meaning is referred to as a semantic structure framed within the mind of a person. Cognitive semantics supports an integrated view of language and thought in which thought/cognition is understood through language. Even Melugin (2009:14) acknowledges that the textual meaning of Isaiah is inevitably influenced by reader bias, reader thought, "Whether one believes that meaning is 'in' texts or thinks instead that meaning is inherently a construct which is in no small measure the creation of the reader, one must surely agree that in practice the interpreter and the interpreter's biases do affect the way a text is actually read. The notion of concept and meaning in cognitive semantics is broad and includes both conventional and novel conceptions as well as sensory, emotive, and kinesthetic perceptions generated from physical, social and linguistic contexts. Semantic structures are the building blocks of cognitive domains. One word or one concept is not limited to one isolated meaning; words are concepts with extended relationships to other words that give a fuller range of meaning. Cognitive semantics allows us to understand the differences in understanding of a concept from people to people.

2 Isa. 43:19: 'Behold, I am doing a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it? I will make a way in the wilderness and rivers in the desert' (RSV). This verse is generally considered a promise for a new deliverance from slavery resembling the first exodus from Egypt.

3 A radial category is a category that is formed with a central model/common example but also contains various extensions. These extensions relate back to the central model through relationships that are not based on definitional rules but rather family resemblance.

4 It is important to note that radial categories have gradations; some members are better or worse examples of the category. In radial categories, better examples are considered more central and have more features of the prototypical case and worse examples are less central members of the category and lack one or more of the properties that define the prototypical member. The central case of a category defines the concept of the category on which the extensions are based.

5 World view theorists from the field of Anthropology such as M. Kearney (1984) and R. Redfield (1953) propose 7 universal world view categories: Self, Other, Relationship, Classification, Causality, Time, and Space. Other is all that is not Self and includes such entities as Earthly Other, Community Other, and Supernatural Other.

6  occurs 6 times in the Isaiah text: Isa. 41:14; 43:14; 47:4; 48:17; 49:7; 54:5. The phrase,

occurs 6 times in the Isaiah text: Isa. 41:14; 43:14; 47:4; 48:17; 49:7; 54:5. The phrase,  is used 25 times in Isaiah alone (see Isa. 1:4; 5:19, 24; 10:20; 12:6; 17:7; 29:19; 30:11, 12, 15; 31:1; 37:23; 41:14, 16, 20; 43:3, 14; 45:11; 47:4; 48:17; 49:7; 54:5; 55:5; 60:9, 14) and just 7 times in other Old Testament books (see 2 Kegs. 19:22; Ps. 71:22; Ps. 78:41; Ps. 89:19; Jer. 50:29; Jer. 51:5; Ezek. 39:7).

is used 25 times in Isaiah alone (see Isa. 1:4; 5:19, 24; 10:20; 12:6; 17:7; 29:19; 30:11, 12, 15; 31:1; 37:23; 41:14, 16, 20; 43:3, 14; 45:11; 47:4; 48:17; 49:7; 54:5; 55:5; 60:9, 14) and just 7 times in other Old Testament books (see 2 Kegs. 19:22; Ps. 71:22; Ps. 78:41; Ps. 89:19; Jer. 50:29; Jer. 51:5; Ezek. 39:7).

7 Oswalt (1998:33) comments the significance of qadös in Isaiah is without question, because it is used by the prophet as the salient defining quality of divine 'otherness'. The root, qadös, is used 69 times with even distribution in Isaiah. Thirty eight of the uses are the substantive Holy One which is a higher percentage than elsewhere in the Old Testament.

8 Isa. 35:9-10: 9'No lion will be there, Nor will any vicious beast go up on it; These will not be found there. But the redeemed will walk there,10 And the ransomed of the LORD will return; And come with joyful shouting to Zion, With everlasting joy upon their heads. They will find gladness and joy, And sorrow and sighing will flee away' (NASB).

9 All references in this paper use the RSV unless otherwise noted.

10 D. Henne (1999) supports this view in his treatment of the title in his preliminary version of Translator's Notes on Isaiah, Appendix 1: Some key words in the books of the Old Testament prophets, unpublished manuscript.

11  from Isa. 41:4 contains a parallel 'with' that is one written form of na for two uses: 'I Yahweh, was with the first, and with the last; I am He.' NIV, TEV and NET translate with this meaning in mind; RSV, NASB, and NLT limit the translation to 'I Yahweh, the first and with the last, I am He.'

from Isa. 41:4 contains a parallel 'with' that is one written form of na for two uses: 'I Yahweh, was with the first, and with the last; I am He.' NIV, TEV and NET translate with this meaning in mind; RSV, NASB, and NLT limit the translation to 'I Yahweh, the first and with the last, I am He.'

12 'I, I am Yahweh.'

13 See Deut. 14:6.

14 Israel as a servant of God (Isa. 41:8-9; 43:10; 48:20; 49:3, 5-6: 54:17); with God as husband to Israel (Isa. 54:5) and God as King of Israel (Isa. 41:21; 43:15) as subsidiary categories of servant.

15  may be translated to reject, despise, or refuse. RSV chooses to translate

may be translated to reject, despise, or refuse. RSV chooses to translate  in Isa. 41:9 as 'cast off': 'You are my servant, I have chosen you and not cast you off

in Isa. 41:9 as 'cast off': 'You are my servant, I have chosen you and not cast you off  .

.

16 see Lev. 25:25-34 (redeem property); Lev. 27:11-13 (redeem animals dedicated to the Lord).

17 see Lev. 25:47-54. Referred to as restitution of kin.

18 see Num. 5:8.

19 Isa. 43:3.

20 Discussed in personal communication with Dr. Andrew Bowling.

21 Isa. 43:7; 48:1, 9, 11.

22 Isa. 49:8 refers to the Israel's land 'heritage' from Yahweh being repopulated; and Isa. 54:17, 'heritage of the servants of the Lord.'

23 Young (2000:138-139) refers to the dilemma of explaining the birth of Israel as a nation because Yahweh essentially created the nation of Israel out of nothing through only the agency of divine grace. Perhaps Isaiah's intent here is to highlight the uniqueness of Israel's theocratic heritage since he chooses the verbs 'created' (arb) & 'formed' (rxy) also used in the creation account (Gen. 1:1; 2:7).

24 See Exod. 3:12 (serve Yahweh on this mountain); Exod. 3:18 (serve Yahweh with sacrifices); II Kgs. 10:23 (serve Yahweh/serve Baal); II Chron. 35:3 (serve by celebrating the Passover); Ps. 100:2 (serve the Lord with gladness).

25 Ringgren (1999:383-384) describes  ('ebed) in terms of serving personal objects in various forms such as a slave serves his master (Exod. 21:6); a son serves his father (Mal. 3:17); an animal serves its owner (Job 39:9); a king serves another king (Gen. 14:4).

('ebed) in terms of serving personal objects in various forms such as a slave serves his master (Exod. 21:6); a son serves his father (Mal. 3:17); an animal serves its owner (Job 39:9); a king serves another king (Gen. 14:4).

26 See Lev. 25:42-55; Deut. 5:15; 15:15.

27 For example, the Hebrew Kingship included the role as leader in war and the one to ensure continuity of national sovereignty and liberty (Johnson 1960:204-235).

28 see Gen. 3:16.

29 For further discussion on the relationship between man and woman, see Wolff (1996:166-176).

30

31 See Ps. 24 :8-10.

32 Weinfeld (1995:34) suggests the terms 'righteousness', 'salvation', and 'glory' are synonyms in Deutero-Isaiah.

33 For court setting, see Exod. 23:2-3, 6; II Sam. 15:2, 4. For formal religious setting see Ps. 35:1; Micah 7:9. Limburg (1969:291-305) argues the narrative in Judg. 10:17-11:11 describes Jephthah negotiating a settlement with the Ammonites through a series of back and forth accusations (rib). This illustrates an international legal process between two parties in a tumultuous relationship.

34 Interestingly, the use of lag in verse 11, 'our Redeemer' or 'our Vindicator', may be considered a parallel of  in such cases as 'defend your cause'. Culver (1980:845) gives Job 19:25, 'my Redeemer' (

in such cases as 'defend your cause'. Culver (1980:845) gives Job 19:25, 'my Redeemer' ( ), as an example of the parallel expression to 'defend your cause'(

), as an example of the parallel expression to 'defend your cause'( ) with an example found in Ps. 74:22.

) with an example found in Ps. 74:22.

35 See Gen. 4:10; Job 16:18; Ezek. 24:7-8.

36 See Morris (1955/56:77-82).

37 Also found in Isa. 34:8; 59:17; 61:2; 63:4 as 'the day of the Lord's vengeance.'

38 Examples of Gō'ēl haddám include: Num. 35:19; Deut. 19:6; Jos. 20:3; and II Sam. 14:11. By custom, the duty fell to the closest consanguineal male relative beginning with the son, then brother, and so forth (see Lev. 25:47-49).

39 See Num. 35:11-13, 25.

40 See Gen. 9:6; Num. 35:30-31.

41 In his discussion of  Smick (1980:599) expressed the opinion that God as redeemer would not truly be holy if he allowed sin to go unpunished. God must be a God of vengeance 'for his mercy to have meaning'.

Smick (1980:599) expressed the opinion that God as redeemer would not truly be holy if he allowed sin to go unpunished. God must be a God of vengeance 'for his mercy to have meaning'.

42 Lipinski (1999:4) comments the practice of revenge ( ) by a Gō'ēl haddam was meant to ensure respect for both the life of the slave and the life of the master since the harm of either could be avenged.

) by a Gō'ēl haddam was meant to ensure respect for both the life of the slave and the life of the master since the harm of either could be avenged.

43 See Whitley (1972:469-75).

44 See Exod. 20:5; 34:7.

45 Harner (1969:418-434) labels five passages in Deutero-Isaiah containing 'Fear not' commands as salvation oracles: Isa. 41:8-13; 41:14-16; 43:1-4; 43:5-7; 44:1-5. He suggests salvation oracles have a somewhat fluid four component pattern of: 1) direct address to recipient; 2) 'Fear not' phrase of reassurance; 3) divine self predication; and 4) a message of salvation with present or future aspect. I believe a fifth salvation oracle is present in Isa. 54:4-8.

46 Watts (1987:104) notes that the formula, 'I am with you', is used commonly in Old Testament history by Yahweh with his chosen people (see Exod. 3:12; Deut. 31:23; Josh. 1:5) and even in the New Testament (see Matt. 28:20). The inference would be, "I am with you just as I have always been".

47  means 'to see,' 'to look at,' or 'to regard.' Only Isaiah uses the verb in the hithpael stem which takes on the meaning of looking around in fear (Isa. 41:10, 23).

means 'to see,' 'to look at,' or 'to regard.' Only Isaiah uses the verb in the hithpael stem which takes on the meaning of looking around in fear (Isa. 41:10, 23).

48 'I am your God' or 'I am Yahweh your God' are descriptive phrases used extensively in the Old Testament that qualify the relationship between Yahweh and Israel. Often these statements are linked to Yahweh's visitation at covenant ceremonies. A particularly good treatment of the topic can be found in Zimmerli (1982), I am Yahweh, Your God.

49 RSV, NIV, NASB, REB, TEV all translate as future imperfective, 'I will'.

50 NET renders this general truth aspect.

51 According to Pedersen (1991:360), 'All fundamental values are given with righteousness; it must create life.'

52 The root nasal (lx]) means to deliver, rescue, or save and is a close concept to ga'al (redeem, set free), halas (break away, deliver, set free), and padá (redeem, deliver, ransom). Often the hiphil form is associated with both physical escape and a sense of spiritual deliverance from transgressions. See Ps. 39:8; 51:14; 69:14; 79:9.

53  is used 30 out of its 38 uses in parallel with

is used 30 out of its 38 uses in parallel with  .

.

54  is used 14 out of its 17 uses in parallel with

is used 14 out of its 17 uses in parallel with  .

.

55 NLT correctly translates the yiqtol verb forms of Isa. 54:4 as a continuing state rather than a future action: 'Fear not; you will no longer live in shame' meaning Israel would not continue in shame. This is in keeping with verse 6, 'For the Lord has called you back from your grief' and verse 7, 'For a brief moment I abandoned you but with great compassion I will take you back.'

56 Proverbs 19:26 is most often translated with the hiphil bos and hap êr as causing shame and bringing reproach on one's parents and not only on the disobedient child.

57 For additional arguments, see A. van Selms (1982:257-69), The Expression 'The Holy One of Israel.'