Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Theologica

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.34 no.2 Bloemfontein 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ACTAT.V34I2.10

The art of creating futures - practical theology and a strategic research sensitivity for the future

J.A. van den BergI; R.R. GanzevoortII

IDepartment of Practical Theology, University of the Free State, South Africa. E-mail: vdbergja@ufs.ac.za

IIFaculty of Practical Theology, VU University, The Netherlands and research fellow Department Practical Theology, University of the Free State, South Africa. E-mail: r.r.ganzevoort@vu.nl

ABSTRACT

This paper explores a futures perspective for practical theology. Although there are some examples of a future orientation, a systematic futures perspective has not been developed. Building on futures studies (including predictive studies on foresight and design and architecture studies), the authors propose a methodological model for future-sensitive practical theology, accounting for the probable, possible, and preferable. The model results in three modes in which practical theology can employ a future orientation: utopian, prognostic-adaptive, and designing-creative.

Keywords: Practical theology, Futures studies, Methodology, Research

Trefwoorde: Praktiese teologie, Toekomsstudie, Metodologie, Navorsing

1. INTROUCTION

Practical theology is a future-oriented discipline, but this dimension of its character and practice is not always acknowledged in research endeavours. That is the claim we make in this paper. We set out to unpack the first half of the claim in describing the orientation on the future. Then we will elaborate on the methodological implications by building on the disciplines of futures studies and design/architecture. The motivational argument for arranging this conversation could be found in the strategic nature and character these disciplines have in common with practical theology. Translating notions of this interdisciplinary exchange into the language of practical theology, we finally discuss the challenges and themes for a practical theological sensitivity towards addressing themes of future relevance.

2. PRACTICAL THEOLOGY AS FUTURE ORIENTED

Although there are many and widely differing definitions of practical theology, most of them would at least agree that it has to do with the theological study of practices or lived religion (Ganzevoort 2009:3). While other theological disciplines focus on the textual sources of a religious tradition or on the systematic conceptual structures, practical theology deals primarily with practices. This is the reason why there is strong overlap with social sciences, just like systematic theology overlaps with philosophy and Biblical theology with the study of languages.

A second point of convergence in thinking about practical theology seems to be that practical theology focuses mostly on contemporary practices. In its focus on religious practices there is an obvious overlap with the historical study of religion, but practical theologians tend to look at practices as they function and evolve in our own days whereas historians of religion look at practices (and ideas and texts) from the far and recent past. Practical theology indeed has a focus on "the tangible, the local, the concrete and the embodied... it remains grounded in practice and stays close to life" (Miller-McLemore 2012:14).

A third point of convergence was identified by Gerben Heitink (1999) when he advocated the combination of empirical-descriptive, hermeneutic-evaluative, and strategic approaches in practical theology. The latter are usually understood to comprise of methods and models for teaching, pastoral care, worship, and so on. More than other disciplines in theology and also more than mainstream social sciences, practical theology often has an action oriented dimension and aims to develop and sustain practices rather than only describe or understand them. This is what Rick Osmer (2008:4,175-176) calls the pragmatic task of practical theology.

Too implicit in these approaches, however, is the dimension of the future. Although the strategic approach could open up the future, it is usually limited to describing viable and functional ways of responding to the present. Pastoral, congregational and societal issues are described and adequate responses are proposed. New modes of working evolve, but it is mostly focused on working in the present, not on anticipating the future and even less on creating one. This may contribute to the predicament we are in, in which we are constantly lagging behind, trying to solve today's (or often yesterday's) problems instead of preventing tomorrow's. Moreover, the position and authority of practical theology suffer from the fact that we are constantly reorienting ourselves to new situations rather than steering consistently into the future.

Taking clues from Sären Kierkegaard, Andrew Lester (1995:12-15) discusses the temporal dimension of pastoral care and counseling. His views can easily be augmented to the wider field of practical theology. According to Lester, the future is a fundamental yet often neglected part of temporality that is essential to human beings. Even though we can only live in the present, the act of remembering brings the past into the present, whereas anticipation and imagination bring out the future into the present. Lester borrows from Kierkegaard the notion that the self consists of necessity, freedom, and possibility. Necessity is closely linked to the past in that it involves the reality that is based on fait accompli. Possibility regards the future in which options are still open. Between necessity and possibility lie the freedom and responsibility to choose how to live our life in the present. Because postulated futures profoundly influence our present choices, we need to give more attention to these often implicit and unspoken futures.

There are to our knowledge only a few contributions that explicitly deal with practical theological futures studies or "futurology", as it was once named. The most important one is Paul Zulehner (1990) who dedicated the final volume of his four-volume "Pastoraltheologie" to pastoral futurology. He starts by describing future expectations of young people and spiritual ways of coping with those expectations. He then engages with futurological theory and develops a threefold approach: "Kairology" deals with understanding the times involving key themes like peace, ecology, gender issues, and media. "Criteriology" discusses the Christian vision of hope in relation to other future orientations. "Praxeology" finally, addresses the options of acting toward that future. These three neatly parallel Heitink's descriptive, normative, and strategic approaches in practical theology.

3. FUTURES STUDIES

In Etienne van Heerden's acclaimed novel, 30 Nagte in Amsterdam [30 nights in Amsterdam], the main character, Henk de Melker, asks a question regarding the special ability of individuals who have the capacity to "open up the horizon" by looking at it in a certain way (Van Heerden 2009:190). This notion of "opening" the horizon by means of one's gaze offers a character sketch of the scientific field of futures studies, owing to the fact that the "assumption behind forecasting is that with more information, particularly more timely information, decision-makers can make wiser decisions" (Inayatullah 2008:1).

The propensity to think about the future can be traced in every period of the history of thought. It is arguably one of the most defining features of the human species, one that Wolfhart Pannenberg (1985) in his theological anthropology aptly described as Weltoffenheit. Humans have an openness toward the world and its possibilities that surpasses the attitude of other animals and allows them to respond to contingent future events and explore the world beyond their immediate living environment. In time and space, humans can transcend their boundaries and develop their lives in ways most animals cannot. This includes centrally their relation to the future.

Because the future is indeed in many ways open and should be seen more as a series of alternative futures rather than as one, our anticipation is never just a description of what is yet to come. In anticipating, we are actively shaping and changing that future. This means that our expectations for the future are to a high degree performative by nature. We create the future in as much as we try to predict it. This may seem problematic in light of the scientific ideal of objectivity, but it fits quite nicely in a more constructionist epistemology. More than that, it allows us to develop desirable future scenarios. The development of a strategic practical theological sensitivity for the future therefore has to encompass these two dimensions: foresight and creation.

These dimensions are directly related to cognitive functions. David Ingvar (1985) coined the term "Memory of the future" to describe the mechanisms of temporal organization of behavior and cognition. The same structures that connect past actions and experiences to our experience of the here and now house the action programs or plans for future behavior and cognition. These programs can be rehearsed and recalled and can therefore be named "memories of the future". They form the basis for anticipation and expectation, planning and ambition. This ability to imagine and design future events is part of the capacity known as "mental time travel" (Suddendorf & Corballis 2007). The notion of "Memory for the future" has been applied as a specific strategy within business studies by Arie De Geus (1997:31) in his book The living company. Recognizing the multiplicity in character of the future, Barbara Adam (2004:300) has opted for the plural form of futures in her expansion of the concept "memory of futures" implicating

a search for paths that guide us towards more appropriate means to take responsibility for the futures of our making.

Tom Lombardo (2008:2) describes this awareness as "future consciousness" or

the human capacity to be conscious of the future, to create ideas, images, goals, and plans about the future, to think about these mental creations and use them in directing one's action and one's life.

It may be useful at this point to build on the development and central tenets in the field of futures studies, a highly interdisciplinary field with varying support for its academic credentials and to a significant degree hidden from a larger audience because the investigations primarily serve the needs of governments, intelligence services and major corporations. Futures studies then are often politicized or commercialized. Traditionally conducted within the space of the economic and management sciences, the purpose of futures research is "to systematically explore, create, and test both possible and desirable futures to improve decisions". Likewise, "futurists with foresight systems for the world can point out problems and opportunities to leaders around the world" (Glenn et al. 2008:Foreword).

There is quite some academic research that could be called futures studies but are not necessarily recognized as such. Models of climate change, demographic development, and secularization, to mention but a few, are in fact futures studies insofar as they aim to predict possible developments in the future. Social architecture, planning and design, and technical innovation are futures studies insofar as they aim to create a possible future.

People who are acting purposefully in terms of their 'projects' (or visions) are participating in the creation of a more desirable future (Spies 1999:12).

This could also be linked to theology, of which David Ford (2011:1) states:

The goal of theology is wisdom, which unites understanding with practice and is concerned to engage with the whole of life.

If this means equipping people with an approach to life that can change the world, it is certainly an example of futures studies.

Roberto Poli (2011) helpfully describes central tenets of futures studies. Important contributions emerged around WWII, spanning from the 1932 radio call by the renowned novelist H.G. Wells for "Professors of Foresight" to Jewish German scholar in law and political sciences Ossip Flechtheim (1943) who started to develop his ideas about futurology as a refugee in the USA during the war. Flechtheim's view, fleshed out in his 1970 Futurologie. DerKampf um die Zukunft (Futurology: the battle for the future) focused on the need to develop a more peaceful and sustainable democratic world and the changes in humanity needed to achieve that. This futurological program sought to overcome the limitations of the technocratic state planning in Eastern Europe and the predictive study of the future in the West.

The Western approach focused on prospective studies that tried to prepare for the future by analyzing past and present situations. It is not the prediction per se that counts in these studies, but the preparation for a contingent world that is in continuous flux in which we have to decide upon certain actions to reach the aims we have set for ourselves. Whereas the Communist model aimed to control and colonize the future, and the Western model assumed more autonomous development allowing mostly for coping responses, Flechtheim consciously adopted a strategic and perhaps utopian model to "liberate the future". This variety of motives has remained, from technocratic colonization to the development of holistic, optimal and sustainable future scenarios (Malloch 2003:4-5). The inclusion of a futures studies perspective in practical theology will therefore always also require ethical evaluation.

These differing approaches to the study of futures first however highlight the need for concepts to speak about the future (Slaughter 2008). The first question we have to answer is how we see the ontological status of future events (Poli 2011). The classical distinction between facta and futura as developed by economist Bernard De Jouvenel (1967) treated the future as a cognitive construct. Facta are real and can be subjected to scientific analysis; futura are not real nor open for scientific scrutiny but only to intuition and the Art of conjecture, the title of his book. This distinction is rejected by Poli as too simple and he adds the concept of latents, "real forces and structures that work below the threshold of visibility".

Poli's latents include Wendell Bell's (2003) notion of "dispositions", structures of reality that have not yet been realized. The fractures of a glass that has not yet fallen, for example, are structural part of reality. The weak spots in the material could even be identified before the glass actually breaks. It is therefore not just a cognitive construct, nor is it a realized factual structure. Dispositions are structures of reality that become visible when the appropriate circumstances occur. Other latents are for example the seeds of the future that are usually acknowledged only after the fact. But even the visible reality (the facta) has more layers than the purely factual. It also includes what was once called affordances, active properties of an object or a situation that solicit interpretations or responses from us and thereby affect the future in specific ways.

The significance for practical theological research is naturally found in the awareness regarding the world of tomorrow, and in the question how a relevant practical theology, informed by futures studies, could play a role therein. Hames (2007:228) points out that, if this method can be embodied in a meaningful way, then the

art of confidently and ethically finding viable paths into the future, negotiating unknown terrain and unprecedented complexity while retaining integrity and relevance,

will be realized. The recognition of the general human capacity to approach the future - which includes specific alternatives and choices and which is formed by structures, perceptions and forces - in a strategic and purposeful manner, falls within the domain of research and study (Lombardo 2008:15-16; Slaughter 2001:2). The objective hereof - and also of the broader field of futures studies - would thus naturally be

to contribute toward making the world a better place in which to live, benefiting people as well as plants, animals, and the life-sustaining capacities of the Earth (Bell 1997:3).

4. FUTURE SENSITIVE METHODOLOGIES

It is self-evident that an important contribution from the field of futures studies lies, precisely, in so-called "prospective thinking", according to which "futurists aim to contribute to the well-being both of now-living people and of the as-yet voiceless people of future generations". To this end, futurists "explore alternative futures - the possible, the probable, and the preferable" (Bell 1997:42). This leads to the conviction that people who are consistently involved in "vistas of hope" are the creators of their own future, since "[t]he future is waiting for our making, not our taking" (Spies 1999:18).

To explore and incorporate the possible implications of a futures studies perspective in practical theology, we need to clarify the different methodologies. Building on a variety of approaches, we propose the following model, loosely based on a brief methodological treatise by Taeke De Jong (1992).

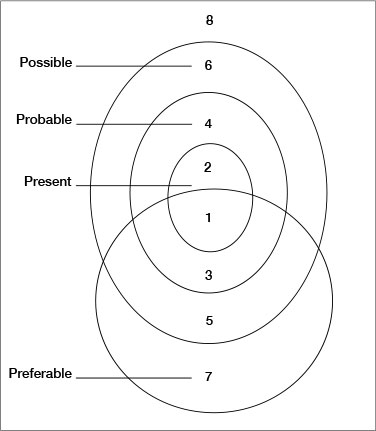

The model takes its starting point in four levels of potentiality. The central circle refers to the present or what could be called actualized reality. The wider circle refers to the probable, which by definition includes the present but is not limited to it. Some things are probable, but not (yet or any more) present. The widest circle refers to the possible, which includes but is not limited to the probable. The lowest circle overlaps these three partially and refers to the preferable. Some parts of the probable, the possible, and the present are also preferable, while other parts of each level of potentiality may be undesirable. (To be precise: differences within and between circles are gradual rather than dichotomous; events are always more or less preferable or probable). This leads to eight areas we should take into account in thinking about futures studies. The focus on one or more of these areas defines the type of futures studies one engages in. It is important to note that all the circles are considered to be dynamic in the sense that they can increase or decrease in size. Certain events and situations may become possible, probable, present, and/or preferable while other events and situations may become less possible, probable, present, and/or preferable. Flying for example generally counted as impossible for centuries, only to be considered as a possibility in the renaissance, as a probability in the nineteenth century and as present reality in the twentieth. Its degree of preferability varied as well, from being religiously suspect to an advanced expression of human mobility to an ecological threat. Social and cultural developments as well as technological innovations influence the size of the circles and therefore of the eight areas we consider here. The example of flying also shows that the location of any event or situation in the model is always an interpretation, made from a specific cultural and normative perspective.

Area 1 and 2 are both part of the present or actualized reality. Area 1 regards those aspects of reality that are both present and preferable. This is the positive and desired state of affairs that usually plays no major visible role in research. Though often implicitly, it is a very central area because it defines the normal taken for granted situation. In that respect, it has strong impact on the normative frameworks we employ in our research. If we consider lifelong church involvement as the normal, preferable present, it immediately affects our description and interpretation of other attitudes toward participation. As long as area 1 stays unreflected, it may in fact be preferable only from the hegemonic perspective, suppressing subaltern voices. When made explicit, this area also contains the best practices we can study with the aim to develop methods to improve practices that are less preferable. Generally speaking, the aim of recommendations flowing from our research is always to enlarge this area, that is: to make present situations more preferable and preferable situations more present.

Area 2 contains those aspects of reality that are present but not preferable. These are events and situations perceived as problematic and the starting point for efforts to correct and amend. Much of our research, also in practical theology, starts with an observation that certain aspects of reality are not preferable. Ecological and social problems challenge us to find solutions. Dysfunctional aspects of churches and families require us to find new modes of relating. Gaps between traditional understanding of the religious tradition and contemporary challenges beg to be overcome. All these problems on the level of our experienced reality can become the impetus for practical theological research. The general aim would be to decrease the size of area 2, that is: to make present situations less unpreferable and unpreferable situations less present.

These two areas of the present allow us to look at the differences between types of research. Descriptive research in principle limits itself to a specific area, aiming at a better understanding of the situation or events at stake. Comparative research would focus on two or more situations or events, often including preferable and non-preferable examples in order to find differences that allow us to develop strategies. Normative research essentially connects situations or events in the present with notions and criteria defining the circle of the preferable, thereby assessing the borderline between areas 1 and 2. Strategic research aims to change and ameliorate situations, which typically involves moving them from area2 through area 3 or 5 (preferable and probable or at least possible) to eventually area 1 (preferable and present).

Areas 3 and 4 together form the probable, with area containing 3 the preferable and area 4 the unpreferable events and situations. These are events and situations that are likely to become present and therefore should be taken seriously. Unpreferable probable events invite us to develop countermeasures and if possible ways to avoid their occurrence. Preferable probable events ask for proactive responses to make the best use of them. These two areas are best known from their role in SWOT-analysis. Area 3 contains the Opportunities and area 4 the Threats. (To complete the model: area 1 includes the Strengths and area 2 the Weaknesses.)

The level of the probable (both preferable and unpreferable) is the main target for predictive futures studies. The challenge here is to identify as specifically as possible elements in this circle and their level of probability. Various methods have been developed for this purpose (Loo 2002:762; Gordon & Pease 2006:321; Wilson & Keating 2007:17-18).The Delphi panel method, though now used for varying purposes, was originally developed for forecasting. It involves a panel of experts offering their expectations and responding in a second round to a summary of these expectations. This structured and interactive process is believed to provide a more substantiated perspective on probable futures. Another widely used method focuses on trends and extrapolations, taking clues from the present reality and trying to assess which signals in that reality might be precursors of significant developments in the future. A third method is the development of scenarios, using known facts and possible variations to describe a set of alternative futures. These futures may be more or less probable and preferable, and the scenarios together allow for the development of plans and protocols to respond to these different outcomes.

Area 5 regards the possible (though not probable) and preferable events and situations. That is: without intervention it is unlikely that such events occur or such situations emerge. They are not impossible, but one cannot predict their occurrence. In spiritual language, this would include miracles and other unpredicted outcomes (including serendipity in scientific research) that ask for receptivity. More importantly in this area, however, is the category of design and innovation. Social and technological developments can make possible events and situations that were deemed improbable at best. The revolution in communication technology for example has allowed billions of people worldwide to access information and connect to sources of knowledge and power. Sustainable energy supply is a similar case in point as is the use of architecture to evoke specific ways of relating and communicating. The key to design studies is the challenge to invent something that does not exist yet and that makes a preferable event or situation more probable or even present. Design studies are not limited to technological or artistic disciplines. The strategic dimension of practical theology similarly can focus on the development of practices and structures that are possible but not yet real.

Area 6 represents the flipside and refers to events and situations that are unpreferable yet possible (though not probable). The best known examples here are disaster scenarios. National and local governments in many places have a strong tradition in developing such scenarios for what is called wildcard events: events with low likelihood but high impact. These are not events we can predict or wish to design, but eventualities for which we need to be prepared. A major force behind this preparation is the fear for lawsuits and claims. Although this culture of suing can be criticized as being built on unrealistic expectations of security (Beck 1986), it does point to the responsibility to be aware of possible threats.

Area 7 considers the utopian: preferable but not possible. Together with 8 (unpreferable and impossible) this is the dimension addressed in science fiction, in visionary dreams, and in our deepest fears. Cultural and religious traditions harbour many stories and images that fit these two areas. In a sense, heaven and hell are their quintessential symbolization. Theological reflection in this area usually falls under the heading of eschatology, involving not only the end of time, but also the qualitatively different transcendent that challenges us to reconsider what we think we know about our present. These two areas then do not refer to possible futures but to the fundamental values (positive and negative) that are important to us. Because of that, they are pivotal in understanding the normative criteria we use to assess present, probable, and possible events and situations and the directions we should or should not take to create the futures we want to become present.

5. IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICAL THEOLOGY

The character of the future displays no regular patterns and its workings are always surprising in an unpredictable manner (Taleb 2007:xix). Our explorations in futures studies show, however, that we can and should engage in anticipating and creating alternative preferable futures. The development of a memory for the future thus calls for a creative and innovative approach to the future, in full awareness of the fact that patterns that were present in the past will not necessarily be repeated. A futures studies approach to practical theology seeks to avoid so-called "zombie" categories: recognized structures of thought and action from the past that prove inapt for meeting present or future challenges (Reader 2008). Instead we try to map out possible research co-ordinates with a view to the further development of a memory for the future. According to De Geus (1997:32), we can distinguish four systemically interrelated movements in developing a memory of the future: 1) adaptability to the external environment (teachability); 2) character and identity (persona); 3) internal and external relationships with people and institutions (ecology); and, lastly, 4) the development thereof over time (evolution). On the basis of the interdisciplinary dialogue between practical theology and futures studies, these movements should be used in the facilitation of a practical theological research design with a sensitivity towards the future.

Now that we have explored some conceptual tools for thinking about the future, we can ask what it would mean for practical theology to be future oriented. In answering this question, we first return to Zulehner's (1990) three dimensions of practical theological futurology. Kairology or discerning the times is primarily located in the present and the probable. It seeks to identify current and emerging issues that can be or become problematic. In that sense it is primarily descriptive and predictive. Criteriology involves the normative discussion about preferable futures. Praxeology refers to designing appropriate responses that connect the problematic issues and criteria for a preferable future, defined by the Christian vision of hope. The description seems to focus more on adaptive responses than on creatively designing a new future, but his model can easily accommodate these wider perspectives.

Based on our model, we can distinguish three attitudes toward the future that can play a significant role in practical theology: the utopian, the prognostic-adaptive, and the designing-creative. We will discuss these attitudes with a link to three kinds of practices that are commonly addressed by practical-theologians: the individual life story, the faith community, and society. Moreover, we will connect the description of these attitudes with the five levels of practical reasoning that Don Browning (1991) identified: vision, obligation, social-environmental context, rules-roles, and tendencies-needs.

5.1. Utopian practical theology

The first attitude is based on the utopian perspective. This attitude focuses on the preferable, non-possible. Because this perspective defines the normative criteria, it is deeply embedded in the visional and obligational levels. According to Browning (1991), our theological thinking is embedded in a tradition that is determined by stories and metaphors that shape our self-understanding. Similarly, Alasdair MacIntyre (1981:216) wrote the famous sentence

I can only answer the question 'What am I to do?' if I can answer the prior question 'Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?'

These visions or narratives offer us fundamental values. Eschatological stories portray how life would be if these values were fully actualized and what would happen if they would be denied altogether. Whichever value is considered - communion, authenticity, freedom, integrity, compassion, joy, acceptance - the stories of heaven give us a glimpse of what really matters in life. As such, they represent alternative futures for us to choose from and the decisions we make in the here and now are intended to foster the preferable rather than the non-preferable alternative futures.

On the level of the individual life story the utopian attitude becomes apparent in our dreams, hopes, and fears. Our deepest desires may not always be realistic (or even probabilistic), but they propel us into a specific direction. Often this is not a conscious process and the clash between infinite aspirations and finite possibilities is at the heart of our existential crises (Gerkin 1979). One of the approaches in pastoral counseling involves the narrative exploration of alternative futures, using for example the "miracle-technique" ("suppose a miracle happened and you would suddenly be in the best possible world, what would it look like?"). Lester (1995:107-114) offers more methods to help people to explore their unreflected future stories. Some of these techniques relate directly to the utopian attitude.

On the level of the faith community the utopian plays a major role in many ecclesiologies. The notion of the church as the "societas perfecta" suggests that the faith community surpasses the natural order of human communities. This should be visible in the moral and spiritual example that the faith community gives to the world. Similarly, the idea of the church as a family of brothers and sisters builds on a metaphor that has utopian overtones. The teachings of Jesus, notably in the Sermon on the Mount, again relate to this utopian dimension. In all these cases, the faith community is challenged to live up to impossible ideals. The gap between expected perfection and realized imperfection reminds the faith community that "it could be otherwise".

On the level of society the utopian is found in science fiction and eschatologies. For practical theology it would also include the vision of a world where people live in peace and harmony and where poverty and injustice are eradicated. In theological terms: the Kingdom of God. Don Cupitt (2000) claims from his analysis of ordinary language that our contemporary leisure culture embodies a realized experience of the Kingdom, but this is only partially true and only for a limited number of people. He is right to suggest that this utopian Kingdom-language is central to advertising, but then again this should be demystified as utopian. Nevertheless, advertisements portraying this utopian world merit theological analysis because they reveal the fundamental myths of our world (cf. Gräb 2002).

For all three levels, practical theologians are called to explore the utopian in its relation with the present. Ideally, the utopian serves to break open the boxed-in stories of the present that leave people in despair. In connecting to the utopian, possibilities emerge and hope is fostered. The utopian may on the other hand also become an escape from reality. That is why practical theologians should always approach the utopian critically, trying to unmask the illusionary.

5.2 Prognostic-adaptive practical theology

The second attitude is the prognostic-adaptive. Here the focus is on the probable, both preferable and non-preferable. The challenge is to be prepared for what can be expected to happen so that the negative effects of events can be avoided or minimized and positive effects can be enlarged. In order to discern this attitude it is important to be aware and sensitive for possible dots of change on the horizon of the future (van der Heijden 2002). In this regard the futures studies methodology of so called environmental scanning

stands at the juncture of foresight and strategy... that allow prepared human minds to discern information, knowledge and insight from the multitude of 'signals' that occur daily... [with] an openness to new data, 'lone signals' and unconventional sources (Slaughter 1999:442).

In our opinion this correlates well with an informed practical theological attitude relating to Browning's (1991) tendency-need level and environmental-social level, because both address the (latent) structures of reality that affect the quality of our existence. The environmental-social refers to the social-structural and ecological constraints of a particular situation and its development through time. Tendencies and needs are in and by themselves premoral goods. Browning states that

the mere existence of these needs, whether basic or culturally induced, never in itself justifies their actualization ... [but] ... [the] higher order moral principles always function to organize, mediate, and coordinate these needs and tendencies (Browning 1991:106).

The debate whether or not tendencies and needs are indeed preferable or not is central to the normative debate in practical theology.

On the level of the individual life story we find this attitude for example in premarital counseling and other pastoral support that helps people anticipate important changes in their lives, including childbirth and retirement. Some life events are so common in a certain life stage that we consciously or unconsciously prepare for them. Training and counseling to prepare for difficult conversations are similarly ways of rehearsing possible responses for future events. These mental actions and interventions aim at facing our fears and constructing alternative responses that may prevent us from losing control. In doing so, they empower us and provide hope that our world will not fall apart and that there will be a future after all. Key questions in pastoral care from this attitude include: What is the worst that can happen? How probable is it? What would you do if this would happen?

On the level of the faith community the prognostic-adaptive attitude is often less prominent. Many communities do not engage in this kind of thinking about the future and preparing for it. The effects of demographic developments on inner-city churches for example, or the consequences of secularization are not always thought through. Other, notably evangelical, communities have a clearer vision for adapting to threats and opportunities and some of them are very effective in finding strategic responses to cultural and societal changes, often through extensive exposure to leadership and marketing literature. This level also yields questions regarding the future orientation of leadership training for theologians (Doornenbal 2012). Theological education should prepare students for labour in a church of the future, while their teachers are often more familiar with the church of the past. This easily creates a mismatch and may lead to failing leadership. We therefore need to reconsider our theology of ministry in light of the changing roles of theologians (van den Berg 2010).

On the level of society we can already foresee several future issues that require theological reflection. The enduring ramifications of the economic and financial crises will become visible in increasing poverty and social upheaval. The sustainability crisis will turn into a shortage of water, food, and energy, probably leading to massive migration and possibly wars. The reshuffling of the international power balance will decrease the influence of individual European countries and increase the position of China, India, and other countries, including military expansion and unprecedented threats. At the same time we can anticipate technological innovations that increase our health and longevity as well as new forms of mobility and communication. Whether these innovations will help avoid the grim scenario or contribute to it, is to be seen. It is precisely here that practical theologians may want to raise a prophetic voice to address the issues of the probable future and call for a life change ("metanoia").

5.3 Designing-creative practical theology

The third attitude is the designing-creative. This attitude accommodates perspectives regarding the possible preferable. The aim in this attitude is not so much to prepare for what may happen, but to envision what we want to see happen. Even more: to facilitate desirable events to occur. This is not necessarily a traditional planning approach, because many things are beyond our control. It is, however, a conscious attempt to change the course of events rather than just to follow it. In considering alternative futures, we come to identify the decisive moments and the actions to be taken in order to create the more preferable ones.

On the individual level this relates directly to the question of desire. Consciously or unconsciously, our desires propel us in the direction they show us. It is one of the most empowering approaches in pastoral care to help people articulate their deepest desires and find appropriate ways of adjusting their lives in that direction. Many of the problems people experience relates not so much to the facts of life per se but to the limitations they see in the realization of this desire (Ganzevoort & Visser 2007). The lack of a desirable future story makes the present an unbearable place. One of the beneficial effects of the empowerment through the articulation of desire is that it invites us to consider what we could actually do in the present to increase the chances of realizing our desires. In doing so, the object of our desire become already more present in our heart (Ganzevoort 2006).

On the level of the faith community we again see the strongest designing-creative attitudes among communities with strong missionary intentions. There are however impressive cases of mainline churches developing a vision for their future existence and role in society and zealously working toward realizing that vision. Examples include the decision to become inclusive churches (sometimes against the wish of a substantial part of the members) and social ministries (responding to the needs of the civil community around them). A specific example would regard a dwindling liberal church in which the members, all ageing, decided to use the church assets to appoint an evangelical minister with a vision to revitalize the congregation. They opted not to cater for their own needs and preferences, but saw the need for a different kind of church and facilitated that.

On the level of society we do well to rekindle our Kingdom perspective and translate that into concrete actions for the transformation of society. This strategic agenda of practical theology is directly related to issues of sustainability, the "principle of surviving and prospering in the long term" (Hames 2007:245). Here we can relate directly to the following key elements as part of a rationale for futures studies and as an orientation towards the future, as identified by Slaughter (2008): Futures perspective involves an active view of decision-making; future alternatives imply present choices; forward thinking is preferable to crisis management and future transformations are certain to occur. The question theologians have to face then is how the Kingdom can become concrete and visible in society. More concretely: how we can facilitate a transformation that fosters love, justice, healing, growth, and harmony. Wonderful examples exist abound throughout history, from Florence Nightingale to the work of so called Truth and Reconciliation Committees functioning in parts of the world with conflict driven histories.

6. CONCLUSION

In this paper we have outlined some of the conceptual and methodological tools we can develop if we want to strengthen the future orientation in the discipline of practical theology. It is not necessarily a new way of doing practical theology, but it offers at least a new perspective that invites practical theologians to be more effective in helping individuals, faith communities, and society at large in living with the contingencies of the future.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adam, B. 2004. Memory of Futures. Krono Scope 4(2):297-315. [ Links ]

Beck, U. 1986. Risikogesellschaft. Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. [ Links ]

Bell, W. 1997. The purposes of future studies. The Futurist Nov-Dec, 3-7. [ Links ]

Browning, D.S. 2003. Foundations of Futures Studies: History, Purposes and Knowledge: Human Science for a New Era Volume 1. New Brunswick: Transaction. [ Links ]

Browning, D.S. 1991. A fundamental practical theology. Descriptive and strategic proposals. Minneapolis: Fortress. [ Links ]

Cupitt, D. 2000. Kingdom come in everyday speech. London: SCMP. [ Links ]

De Geus, A. 1997. The living company. Growth, learning and longevity in business. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing. [ Links ]

De Jong, T. 1992. Kleine methodologie van ontwerpend onderzoek. Meppel: Boom. [ Links ]

De Jouvenel, B. 1967. The art of conjecture. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson. [ Links ]

Doornenbal, R.J.A. 2012. Crossroads. An Exploration of the Emerging-Missional Conversation witg a Special Focus On 'Missional Leadership' and Its Challenges for Theological Education. Delft: Eburon. [ Links ]

Fleohtheim, O.K. 1943. Futurologie. Historisches Wórterbuch derPhilosophie. Basel, Switzerland: Schwabe & Co Verlag. [ Links ]

Fleohtheim, O.K. 1970. Futurologie. Der Kampf um die Zukunft. Kóln: Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik. [ Links ]

Ford, D.F. 2011. The future of Christian theology. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. [ Links ]

Ganzevoort, R.R. 2006. The social construction of revelation. International Journal of Practical Theology 8(2):1-14. [ Links ]

Ganzevoort, R.R. 2009. Forks in the road when tracing the sacred. Practical theology as hermeneutics of lived religion. Paper presented at the International Academy of Practical Theology, Chicago. [ Links ]

Ganzevoort, R.R., & Visser, J. 2007. Zorg voor het verhaal. Achtergrond, methode en inhoud van pastorale begeleiding. Zoetermeer: Meinema. [ Links ]

Gerkin, O.V. 1979. Crisis experiences in modern life. Theory and theology in pastoral care. Nashville: Abingdon. [ Links ]

Glenn, J.C., Gordon, T.J., & Floresou, E. 2008. State of the future. Washington: The Millennium Project. World Federation of UN Associations. [ Links ]

Gordon, Τ. & Pease, A. 2006. RT Delphi: An efficient "round-less" almost real time Delphi method. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 73:321-333. [ Links ]

Gräb, W. 2002. Sinn fürs Unendliche. Religion in der Mediengesellschaft. Gütersloh: Kaiser. [ Links ]

Hames, R.D. 2007. The five literacies of global leadership. What authentic leaders know and you need to find out. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Heitink, G. 1999. Practical theology. History, theory, action domains. Manual for practical theology. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Inayatullah, S. 2008. Methods and epistemologies in Future Studies. In R.A. Slaughter (Ed.), Knowledge Base of Futures Studies CD-ROM. Indooroopilly QLD: Foresight International. [ Links ]

Ingvar, D.H. 1985. "Memory of the future". An essay on the temporal organization of conscious awareness. Human Neurobiology 4(3):127-136. [ Links ]

Lester, A.D. 1995. Hope in pastoral care and counseling. Louisville (Ky): Westminster John Knox. [ Links ]

Lombardo, Τ. 2008. The evolution of future consciousness. Bloomington: Authorhouse. [ Links ]

Loo, R. 2002. The Delphi method: a powerful tool for strategic management. International Journal of Policy Strategies & Management 25(4):762-769. [ Links ]

MacIntyre, A. 1981. After virtue: A study in moral theory. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [ Links ]

Malloch, T.R. 2003. Social, human and spiritual capital in economic development. Templeton Foundation, Working group of the spiritual capital project: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Miller-McLemore, B.J. 2012. Introduction: The contributions of practical theology. In B.J. Miller-McLemore (Ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Practical Theology (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell) , pp.1-20. [ Links ]

Osmer, R.R. 2008. Practical Theology. An introduction. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Pannenberg, W. 1985. Anthropology in theological perspective. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. [ Links ]

Poli, R. 2011. Steps toward an explicit ontology of the future. Journal of Futures Studies 16(1):67 - 78. [ Links ]

Reader, J. 2008. Reconstructing practical theology. The impact of globalization. Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Slaughter, R.A. 2001. Knowledge creation, futures methodologies and the internal agenda. Foresight 35/407-418. [ Links ]

Slaughter, R.A. 2008. Future concepts. In R.A. Slaughter (Ed.), Knowledge Base of Futures Studies CD-ROM.: Foresight International. [ Links ]

Suddendorf, Τ., & Corballis, M.C. 2007. The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behavioral and Brain Science 30(3):299-313. [ Links ]

Taleb, N.N. 2007. The black swan. The impact of the highly improbable. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Van den Berg, J.A. 2010. An autobiographical theologia habitus. Futures perspectives for the workplace. Acta Theologica Supplementum 13. [ Links ]

Van der Heijden, K. 2002. The sixth sense. Accelerating organizational learning with scenarios. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Van Heerden, E. 2009. 30 Nagte in Amsterdam. Capetown: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Wilson, J.H. & Keating, B. 2007 [5th Ed.]. Business Forecasting with Accompanying Excel-based ForecatsXTM Software. USA: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Zulehner, P. 1990. Pastoraltheologie Band 4: Pastorale Futurologie. Düsseldorf: Patmos. [ Links ]