Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.34 suppl.19 Bloemfontein 2014

What happened to the Galatian Christians? Paul's legacy in Southern Galatia

Cilliers Breytenbach

Humboldt-Universität, Stellenbosch University, South Africa. E-mail address: cilliers.breytenbach@cms.hu-berlin.de

ABSTRACT

Paul's Letter to the Galatians points to the influence of his missionary attempts in Galatia. By reconstructing the missionary journeys of Paul and his company in Asia Minor the author argues once again for the south Galatian hypothesis, according to which the apostle travelled through the south of the province of Galatia, i.e. southern Pisidia and Lycaonia, and never entered the region of Galatia proper in the north of the province. Supporting material comes from the epigraphic evidence of the apostle's name in the first four centuries. Nowhere else in the world of early Christianity the name Παύλος was used with such a high frequency as in those regions where the apostle founded the first congregations in the south of the province Galatia and in the Phrygian-Galatian borderland.

Keywords: : Paul's missionary journeys; North/South Galatian hypothesis, Epigraphical evidence: Name "Paul"

Trefwoorde: Paulus se sendingreise, Noord-/Suid-Galatehipotese, Epigrafiese Getuienis: Naam "Paulus"

1. INTRODUCTION

Even though Barnabas and Paul were sent by the church of Antioch on the Orontes to the province Syria-Cilicia to spread the gospel on Cyprus and they then went to Asia Minor,1 it was only Paul who revisited Lycaonia (cf. Acts 16:1-5; 18:23). The epigraphical material referred to here, will illustrate that more than anyone else, Paul left his mark on Lycaonian Christianity.2 From the scant evidence available, it is clear that the Pauline letters and the First Letter to Timothy had an impact on the region. The question of the influence of Paul's Letter to the Galatians is more complex.

Can the Letter to the Galatians contribute to a study of the rise of Christianity in Lycaonia? It is a matter of dispute, whether the letter for the Galatians is addressed to churches in the south of the province of Galatia, that would be southern Pisidia and Lycaonia or to churches in the north of the province, to the region of Galatia proper (Sänger 2010). The major reasons for the dispute can be summarized briefly.3

The Letter to the Galatians was sent to the "churches of Galatia" (Gal. 1:2). In the letter, Paul addressed them as "foolish Galatians" (Gal. 3:1). Unfortunately, neither expression is specific enough. Γαλατία can refer to either the Caesarean province of Galatia or merely to the traditional land of the Galatians in the north of the province (Breytenbach 1996:150-1). Given this ambiguity, on Gal 1:2 alone the Galatian churches could be in the south or the north of the province of Galatia. Clearer is "Galatian". As an ethnic term Γαλάτης designates people of Celtic descent. Nevertheless, it does not determine the locality of the person (Freeman 2001:6-7). Galatians lived at various places in the Roman Empire.4 This is also true for Asia Minor.5 The Galatian king Amyntas reigned over the whole area from Galatian proper to the Pamphylian coast and he resided at Isaura Nea in the Taurus Mountains before he was killed by the mountain tribes in 26 B.C.E. The ruins of his fortifications are still visible in the Isaurian area at Zengibar Kalesi and on the Baş Dağ (Darbyshire, Mitchell & Vardar 2000:89). From Strabo (12.62 [568]) we know he had more than 300 flocks of sheep grazing the Lycaonian plain. It is therefore no wonder that various people of Galatian descent lived in the south of the province of Galatia6 and evidence of Galatian personal names is spread widely south of the Galatian region into Lycaonia,7 in Vetissus,8 insuyu (ancient Pilitokome),9 Philomelium,10 Loadicea Combusta,11 Iconium,12 Lystra,13 Kavak,14 Kilistra,15 Dinek,16 Salarama,17 Madensehir,18 Sidemaria,19 down to Termessus20 in Pisidia and Perge in Pamphylia.21

Since the evidence of the superscription, the praescriptio and Galatians 3:1 is thus inconclusive, a solution of the problem cannot be found without attending to the information the Acts of the Apostles gives on Paul's visits to eastern Pisidia, Lycaonia, Phrygia and Galatia.

2. THE APOSTLE PAUL AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE "GALATIAN" CHURCHES

Initially Barnabas and Paul were sent by the church in Antioch on the Orontes to proclaim the word on Cyprus. Since Barnabas was a Jew from Cyprus, they would have known how to plan the journey. In Paphos on Cyprus, as the author of Acts tells us in Acts 13:6-12, he met Sergius Paul (l) us, called in Greek ό  νθύπατος, which is a usual translation for the Latin proconsul (Mason 1974: s.v. and p. 106). The text of Acts 13:7 probably refers to Lucius Sergius Paullus22 and not to a Q(uintus) Ser[gius Paullus] who might be a construct of modern epigraphy.23 The Sergii Paulii were citizens of the colony in Antioch on the Pisidian border and landowners near modern Sinanli in the region of Vetissus on the border between the Galatian Ancyra and Laodicea Combusta in western Lycaonia (Mitchell 1993:1:151-52). It is most probable that the connections between Sergius Paul(l)us in Paphos and the ruling class in Antioch influenced Paul and Barnabas' decision to go there and that it facilitated their journey (See also Mitchell 1993:2:6-7; Breytenbach 1996:42-43).

νθύπατος, which is a usual translation for the Latin proconsul (Mason 1974: s.v. and p. 106). The text of Acts 13:7 probably refers to Lucius Sergius Paullus22 and not to a Q(uintus) Ser[gius Paullus] who might be a construct of modern epigraphy.23 The Sergii Paulii were citizens of the colony in Antioch on the Pisidian border and landowners near modern Sinanli in the region of Vetissus on the border between the Galatian Ancyra and Laodicea Combusta in western Lycaonia (Mitchell 1993:1:151-52). It is most probable that the connections between Sergius Paul(l)us in Paphos and the ruling class in Antioch influenced Paul and Barnabas' decision to go there and that it facilitated their journey (See also Mitchell 1993:2:6-7; Breytenbach 1996:42-43).

Paul's Roman citizenship might also have played a role, since he seems to have had a preference for Roman military colonies (Breytenbach & Zimmermann, forthcoming). Not only did he start his proclamation of the gospel to the gentiles in the colonies connected by the eastern branch of via Sebaste (Antioch, Iconium and Lystra). On his second missionary journey he also moved to the colony at Alexandria on the Troad (Hemer 1975), which he visited at least three times (Acts 16:8; 2 Cor. 2:12; Acts 20:1, 6-12). He often travelled via this port to Philippi and then to Corinth (Acts 16:11-12; 18:1, then 2 Cor. 2:12 and 7:5, and again Acts 20:1-6), both being Roman colonies. It was in Corinth that he planned to reach the colony at Tarraco on the east coast of the Iberian Peninsula with the help of the Christians in Rome (Rom. 15:22, 28; 16:1, 23).

Once Barnabas and Paul had left Paphos on Cyprus and reached the Roman controlled harbour in Perge in Pamphylia (Acts 13:13), the southern branch of via Sebaste could have enabled these first Christian missionaries to circumvent the insurmountable western Taurus. For their initial journey to the colony at Antioch though, the author merely mentions they passed on from Perge and arrived in the Pisidian Antioch (Acts 13:14). When they returned from Antioch through Pisidia to Attaleia (Acts 14:24-25), they could have taken the western branch of the via Sebaste through the Roman colony at Comama. Since it is stated however, that they "travelled through" Pisidia (διελθόντες τ ν Πισιδίαν; cf. Danker 2000: s.v. διέρχοµαι) back to Perge in Pamphylia (Acts 14:21, 24), they might rather have used the road skirting the southern edge of Lake Coralis (Mitchell 1993:1:78-80). The author states that they spoke the word in Perge, not implying that they proclaimed the gospel whilst travelling through the Pisidian Mountains.

ν Πισιδίαν; cf. Danker 2000: s.v. διέρχοµαι) back to Perge in Pamphylia (Acts 14:21, 24), they might rather have used the road skirting the southern edge of Lake Coralis (Mitchell 1993:1:78-80). The author states that they spoke the word in Perge, not implying that they proclaimed the gospel whilst travelling through the Pisidian Mountains.

Since the original foundation of the city Antioch on the Pisidian border in the 3rd century B.C.E. a Jewish community might have lived there.24 They must have survived the foundation of the Roman colony by Augustus in 25 B.C.E., for in Acts 13:14b-43 the author of Acts placed the speech of Paul on the Sabbath in the synagogue in Antioch. He follows his normal narrative pattern: Paul has considerable success and the local Jews stir opposition. Nevertheless, the narrative claims in Acts 13:49 that the Christian message spread through the whole territory of Antioch (διεφέρετο δ ό λόγος το

ό λόγος το

υρίου δι'

υρίου δι'  λ

λ ς της χώρας).25 In the city's territory, the "word" was first spread in Asia Minor in a rural area. This was an area in which the local population had been Hellenized since the foundation of the Greek city. When the Augustan colony was founded, deducted veterans were settled on the territory and the legio VII Claudia was stationed here for quite a while (Breytenbach & Zimmermann, forthcoming). Such factors increased the cosmopolitan nature of the city and its territory. It was thus possible for Barnabas and Paul to use Greek to communicate with the rural population.

ς της χώρας).25 In the city's territory, the "word" was first spread in Asia Minor in a rural area. This was an area in which the local population had been Hellenized since the foundation of the Greek city. When the Augustan colony was founded, deducted veterans were settled on the territory and the legio VII Claudia was stationed here for quite a while (Breytenbach & Zimmermann, forthcoming). Such factors increased the cosmopolitan nature of the city and its territory. It was thus possible for Barnabas and Paul to use Greek to communicate with the rural population.

According to Acts 13:50, the local Jews in Antioch incited the "pious women of repute and the first men of the city" (τ ς σεβοµένας γυνα

ς σεβοµένας γυνα ας τ

ας τ ς εύσχήµονας

ς εύσχήµονας  αι το

αι το ς πρώτους τῆς πόλεως). It is crucial to look carefully at the terminology used here. The πρώτοι της πόλεως formed the group from which the duoviri governing the Roman colony came.26 The expression εύσχήµοναι most probably refers to women of nobility (Spicq 1994: s.v.) and translates the Latin honestae (Mason 1974: s.v). The members of the ruling class in Antioch thus expelled Barnabas and Paul from their territory (έ

ς πρώτους τῆς πόλεως). It is crucial to look carefully at the terminology used here. The πρώτοι της πόλεως formed the group from which the duoviri governing the Roman colony came.26 The expression εύσχήµοναι most probably refers to women of nobility (Spicq 1994: s.v.) and translates the Latin honestae (Mason 1974: s.v). The members of the ruling class in Antioch thus expelled Barnabas and Paul from their territory (έ έβαλον αύτοὺς άπὸ τῶν ὁρίων αὐτῶν),27 i.e. the territorium of the Antiochia colonia Caesarea. This definitely made it difficult for Paul and Barnabas to return to the city itself, but it would have been easier to return to the villages on the territory of the colony.

έβαλον αύτοὺς άπὸ τῶν ὁρίων αὐτῶν),27 i.e. the territorium of the Antiochia colonia Caesarea. This definitely made it difficult for Paul and Barnabas to return to the city itself, but it would have been easier to return to the villages on the territory of the colony.

Expelled from the territory of Antioch they took the via Sebaste eastwards through the mountains to Lycaonia to establish Christian congregations in the neighbouring Roman colonies in Iconium and Lystra (Acts 13:51; 14:1, 6). It is notable that, according to Acts 14:6, they did not go to the cities only, but also to the περίχωρος, the area around these two cities. The territories of Iconium and Lystra shared a common border.28 Again Paul and Barnabas planted the seeds of Christianity in a rural area. Again this is an area where Augustus settled veterans when the colony was founded (Breytenbach & Zimmermann, forthcoming).

According to the narrative of Acts, the Jews forced Paul and Barnabas to flee from Iconium to Lystra and then further on to Derbe (Acts 14:5-6, 19-20). As the crow flies, ancient Derbe is located ca. 100 kilometres east-southeast of Lystra. In this rather small city on the route from Iconium and Lystra to the Cilician Gates (Ballance 1957:147-51), Barnabas and Paul preached the gospel and caused a relatively large number to become disciples. Hereafter they returned to Lystra, Iconium and Antioch (Acts 14:21-22). Acts 14:23 explicitly states that they appointed elders in every congregation: "with prayer and fasting they entrusted them to (the protection of) the Lord in whom they had come to believe."

After the meeting of the apostles in Jerusalem (Gal. 2:1-10; Acts 15), Paul and Silas left Antioch on the Orontes for the apostle's so called second missionary journey (Acts 15:40). From the parallel journey of Barnabas and John Mark to Cyprus, it is clear that the congregation in Antioch on the Orontes planned to strengthen the newly founded congregations and to inform the presbyters on the decisions of the meeting of the apostles. Acts 16:1 tells us that Paul came to Derbe and Lystra, visiting Derbe for a second and Lystra for a third time. In Lystra, Timothy joined Paul and Silas (Acts 16:1-2). Acts 16:4 implies that Paul also went through Iconium for a third time. Even if the remark in Acts 16:5 that the numbers of the churches increased daily may just fit in with Luke's narrative strategy, it is reasonable to accept that Paul's visit strengthened the faith of the believers. The impression that the author of Acts leaves, is that there were thriving congregations in Derbe, Lystra, and Iconium. This time Antioch on the Pisidian border is not mentioned or implied.

Turning to Acts 16:6 it is clear that Paul and his co-workers planned to go to into the Province of Asia.29 As the author of Acts expresses it, they were "hindered by the Holy Spirit". It is necessary to analyse this remark in more detail: Διῆλθον δὲ τὴν  ρυγίαν

ρυγίαν  αι γαλατικὴν χώραν

αι γαλατικὴν χώραν  ωλυθέντες ὑπὸ τοῦ ἁγίου πνεύµατος λαλῆσαι τὸν λόγον έν τῆἈσίᾳ (Acts 16:6).

ωλυθέντες ὑπὸ τοῦ ἁγίου πνεύµατος λαλῆσαι τὸν λόγον έν τῆἈσίᾳ (Acts 16:6).

The first part refers to the route Paul, Silas and Timothy actually took. Both φρυγίαν and γαλατική can be adjectival30 to τὴν χώραν allowing two possible interpretations. Either they went through the Phrygian-Galatian χώρα, or through the Phrygian and through the Galatian χώρα. Interpreting χώραν as meaning "region, land" and respecting the intermediate position of the co-ordinated adjectives,31 the phrase can best be translated with "the Phrygian-Galatian land" and refers to the Phrygian-Galatian borderland beyond the western Sultan Dağlari.

It is also necessary to determine the function of the participle  ωλυθέντες. Since in Greek the aorist participle lacks relative time (Blass & Debrunner 200:§339,1), its relation to the action expressed by the main verb in the aorist is determined by the context (Zerwick 1963:§264-65). Thus two different readings have been proposed for Acts 16:6: "They (sc. Paul, Silas and Timothy) went through the Phrygian-Galatian region, because they had been hindered by the Holy Spirit to proclaim the word in Asia" (Haenchen 1965:424; Schneider 1982:205 n. 14). This reading is to be preferred to the grammatically unconvincing reading "After they had gone through the Phrygian-Galatian region, they were hindered by the Holy Spirit to proclaim the word in Asia."32

ωλυθέντες. Since in Greek the aorist participle lacks relative time (Blass & Debrunner 200:§339,1), its relation to the action expressed by the main verb in the aorist is determined by the context (Zerwick 1963:§264-65). Thus two different readings have been proposed for Acts 16:6: "They (sc. Paul, Silas and Timothy) went through the Phrygian-Galatian region, because they had been hindered by the Holy Spirit to proclaim the word in Asia" (Haenchen 1965:424; Schneider 1982:205 n. 14). This reading is to be preferred to the grammatically unconvincing reading "After they had gone through the Phrygian-Galatian region, they were hindered by the Holy Spirit to proclaim the word in Asia."32

What is meant by ἐν τῇ Άσίᾳ? Haenchen's (1965:424) dictum, that in this context "Asia" means the same as in the Apocalypse, and thus refers to Ephesus, needs to be revised. There are two reasons for this stance. In the first instance, for geographical reasons Acts 16:6 cannot easily be interpreted in such a way that Paul entered Asia, proceeded to Ephesus, and then had to turn back. Secondly, if the participle  ωλυθέντες furnishes a reason as to why Paul and his company took the direction they did, the obvious interpretation is that Paul, Silas and Timothy were prevented from entering the major Asian cities on the route from Iconium into Asia via Apamea or even Eumeneia. Acts 16:6b rather implies that after passing north the Sultan Dağlari, they did not turn southwestwardly to enter Asia, but turned north.33

ωλυθέντες furnishes a reason as to why Paul and his company took the direction they did, the obvious interpretation is that Paul, Silas and Timothy were prevented from entering the major Asian cities on the route from Iconium into Asia via Apamea or even Eumeneia. Acts 16:6b rather implies that after passing north the Sultan Dağlari, they did not turn southwestwardly to enter Asia, but turned north.33

It is preferable to let the inherent ambiguity of the text of Acts 16:6 prevail and to accept the coincidence of the actions expressed by the participle and the main verb: "They went through the Phrygian-Galatian region, being hindered by the Holy Spirit to proclaim the word in Asia". The last remark is in line with the narrative concept of the author of Acts. The Holy Spirit preformatted all vital decisions of the church (cf., e.g., Acts 1:2; 13:2, 4; 15:28; 19:21).

According to the narrative of Acts, Paul, Silas and Timothy were hindered to proclaim the word in Asia. The text implies that they planned to travel into the Province Asia. This means that according to the geographical conception undergirding the narrative, from Iconium they headed northwestwardly along the Sultan Daglari to reach Asia and not directly northwards into Galatia proper.34 But they would not just have ventured aimlessly into Asia. Paul's missionary strategy required a Hellenized environment (Haenchen 1965:426-427), because he had to rely on the Greek language for communication and Greek was the lingua franca only in cities. In the villages, the vernacular prevailed. They would have taken a specific route and would have tried to enter specific cities in Asia. One may speculate which cities in Asia could have been on their itinerary. It would be a logical presumption that Paul, Silas and Timothy planned to take the central Anatolian road from Cilicia in the east.35 This major westward route into the Province of Asia ran through Apamea, Colossae and Laodicea ad Lycum. A few kilometres to the west, where the Lycus meets the Meander, it joined the Ephesian road built by M. Aquillus. This Roman road facilitated travel through Tralles and Magnesia ad Meandrum to Ephesus on the Ionian coast.36

The reader of Acts 16 it is not quite clear from which location Paul, Silas and Timothy set out to Asia, but we should take the determined τὰς πόλεις in 16:4 to refer back to the cities mentioned in 16:1-2, Lystra and Iconium.37 From Iconium Paul and Silas thus could have tried to go via Antiochia on the Pisidian border to Apamea, but since Antioch is not mentioned and the area south of the Sultan Daglari can hardly be referred to as "Phrygian-Galatian land," it is more plausible to accept that Paul and his fellow workers took the route on the northern side of the mountains via Loadicea Combustra (modern Ladik), Tyriaeum (Ilgin) and Philomelium (Aksehir). The road from Philomelium to Apamea went south of Synnada (Şuhut).38

Why did Paul deviate from this route into Asia? The narrator explained these events as the work of the Spirit. Weiser (1985:405) wisely advises us to distinguish between Luke's perspective and what might have happened to Paul. In our effort to suggest a historical explanation, we focus on the latter question. Schneider (1982:205), drawing on Galatians 4:13-15, considers the possibility that Paul fell ill. This explanation, apart from building on the Northern Galatian hypothesis, presupposes that a sick Paul ventured into less known regions. Why did he not simply recover in Philomelium or Apamea? Pesch (1986:101), Roloff (1981:241) and Jervell (1998:416) consider external obstacles and troubles.39 Which events could be probable from a historical and geographical perspective?40

Firstly, the Galatian conflict on the necessity of circumcising non-Jews when integrating them into the children of Abraham, was most probably located around the via Sebaste (Breytenbach 1996:127-147). The conflict on the circumcision of Timothy that Acts 16:1-5 refer to, was also emerging from tensions caused by the integration of uncircumcised persons into Christianity. It, too, was located in Lystra along the via Sebaste. Given the fact that on his first journey Paul had to flee from Antioch and Iconium due to Jewish intervention (Breytenbach 1996:45-52; Acts 13:50; 14:1-5), in the meantime these conflicts could easily have spilled over to Apollonia with the via Sebaste and westward to Apamea. It is highly probable that the Jewish communities in the neighbouring cities had been warned beforehand and prevented his journey.

There might be another reason, too. Since the meeting of the apostles in Jerusalem (Gal. 2:1-10; Acts 15) Paul himself was committed to preach to the uncircumcised. Were he to go down the route to Apamea or westwards to Eumeneia und Acmonia, he would enter the area in central Asia Minor where strong Jewish communities were residing.

Jewish synagogues were confined to the cities along the major routes.41 Late 1st to 2nd centuries C.E. epigraphic evidence from Apollonia shows traces of Jewish families.42 In Pauline times though, a strong community of Jews was also present at Apamea on the upper tributary of the Meander (Cicero, Pro Flacco 28.68; Mitchell 1993:2:35; Ameling 2004:380-382). The origin of these Jewish communities dates back to the times of Antiochus the Great.43 Although by the middle of the 1st century C.E. the local leaders as well as the Romans acknowledged the rights of the Jews in Laodicea on the Lycus (Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae 14.241-243), in 62 C.E. the Roman governor of Asia, L. Valerius Flaccus (Halfmann 1979:101-102), ordered the confiscation of the gold collected by the Jews for the temple in Jerusalem. The annual amount of twenty Roman pounds indicates the considerable size of the Jewish community.44 Jewish presence in the Lycus valley was by no means confined to Laodicea.45 Although the epigraphic evidence from Tralles (Ameling 2004: no. 28; Trebilco 1991:157-158) and Hierapolis46 is later, one might suggest on literary evidence that by the 1st century C.E., Jewish families lived in all the cities of the Lycus valley that had easy access to the main road leading to the Ionian coast, especially to Ephesus:47 Magnesia, Tralles, Antiochia ad Meandrum, Laodicea, Hierapolis and Colossae.48

Important cities along major routes with thriving Jewish communities49 like Apamea on the koine hodos from Ephesus to Tarsus, Eumeneia northwest of the road, and Apollonia on the via Sebaste, show no trace of Christianity in the 1st century, and for the late 2nd and 3rd centuries the influence of the local Jewish communities on the Christians is well attested (Eusebius, Historia ecclesiastica 5.16, 18, 22, 24; Mitchell 1993:2:40-41). Given the location of Apollonia on the via Sebaste west of Antioch and Apamea on the koine hodos between Iconium, Laodicea Combusta, Philomelium in the east and Colossae, Laodicea ad Lycum and Hierapolis in the west, their large Jewish population and the patterns of the expansion of Christianity, it is remarkable that Christian communities emerge here only since the 2nd century. Apollonia and Apamea showed no traces of Christianity in the first hundred and fifty years of its expansion. The obvious explanation is that the Lycus valley was Christianised from Ephesus in the west.50 It is highly probable that because of local Jewish resistance towards the Pauline mission, it was initially impossible to extend the Pauline sphere of influence from Lystra and Iconium westwards along the via Sebaste beyond Antioch to Apollonia and Apamea or along the koine hodos running north of the Boz Dağ and the Sultan Dağlari down to Apamea and eventually Eumeneia. After the meeting of the Apostles, Paul had to change his direction on his so called second missionary journey (Acts 16:6). He did this after the incident concerning the circumcision of Timothy in Lystra (Acts 16:1-5). After travelling north of the Boz Dağ via Laodicea Combusta and along the Sultan Dağlari to Tyriaeum and Philomelium, he went to Troas and then to Macedonia (Acts 16:7-8). Paul might have been forced by Jewish opposition to his gospel to the uncircumcised to change his direction, but he also honoured the agreement of Jerusalem and went to the Macedonians, leaving areas where Jewish communities were known to live to Peter and the others (cf. Gal. 2:9).

On his third missionary journey, according to Acts 18:23, Paul, visiting one location after the other ( αθε

αθε ῆς; cf. Danker 2000: s.v.), moved through (διερχόµενος) τὴν γαλατικὴν χώραν

ῆς; cf. Danker 2000: s.v.), moved through (διερχόµενος) τὴν γαλατικὴν χώραν  αι Φρυγίαν. The last phrase was not translated, because its interpretation is disputed (Breytenbach 1996:114-115). As in Acts 2:10, Φρυγίαν is to be read as a name. The adjective γαλατικήν determines τὴν χώραν as Galatian. Since the expression χώρα denotes either land or an administrative region (praefectura or vicus) (Mason 1974: s.v), it is impossible to determine the exact reference of the expression in Acts 18:23. Paul came from Antioch on the Orontes. He strengthened "all the Christians" (πάντας τοὺς µαθητάς). Since Acts presuppose no other Christian communities in Galatia than those mentioned before in chapters 13-14 and 16:1-5, the most natural assumption is that Paul revisited these communities. Derbe, Lystra and Iconium, all in Lycaonia, were administered as part of the Province of Galatia (Breytenbach 1996:109-112). If one were to take γαλατικὴ χώρα to refer to the province, the phrase would make sense. From here Paul and his company went to Phrygia. Such a reading of Acts 18:23 is enhanced by the interpretation of Acts 16:6 above. Paul and his company then came from Antioch on the Orontes, passing through Derbe, Lystra and Iconium for the third time. This would make a lot of sense, since a local from Lystra, Timothy, was accompanying him. Paul would have passed on the northern side of the Sultan Dağlari, travelling for a second time through Laodicea Combusta, Tyriaeum and Philomelium.

αι Φρυγίαν. The last phrase was not translated, because its interpretation is disputed (Breytenbach 1996:114-115). As in Acts 2:10, Φρυγίαν is to be read as a name. The adjective γαλατικήν determines τὴν χώραν as Galatian. Since the expression χώρα denotes either land or an administrative region (praefectura or vicus) (Mason 1974: s.v), it is impossible to determine the exact reference of the expression in Acts 18:23. Paul came from Antioch on the Orontes. He strengthened "all the Christians" (πάντας τοὺς µαθητάς). Since Acts presuppose no other Christian communities in Galatia than those mentioned before in chapters 13-14 and 16:1-5, the most natural assumption is that Paul revisited these communities. Derbe, Lystra and Iconium, all in Lycaonia, were administered as part of the Province of Galatia (Breytenbach 1996:109-112). If one were to take γαλατικὴ χώρα to refer to the province, the phrase would make sense. From here Paul and his company went to Phrygia. Such a reading of Acts 18:23 is enhanced by the interpretation of Acts 16:6 above. Paul and his company then came from Antioch on the Orontes, passing through Derbe, Lystra and Iconium for the third time. This would make a lot of sense, since a local from Lystra, Timothy, was accompanying him. Paul would have passed on the northern side of the Sultan Dağlari, travelling for a second time through Laodicea Combusta, Tyriaeum and Philomelium.

Our overview has shown that Barnabas and Paul spread the message of Christianity in Antioch and its territory, in Lycaonia in Iconium, Lystra and surrounding areas, and in Derbe. They stayed longer in Derbe and revisited the three Roman colonies on their way back, appointing presbyters. Later Paul and Silas revisited Derbe, Lystra and Iconium and took the road north of the Sultan Dağlari through Laodicea Combusta, Tyriaeum and Philomelium. On his final journey through the area, Paul travelled again through Derbe, Lystra and Iconium Laodicea Combusta, Tyriaeum and Philomelium. This was his third visit to Derbe and the fourth one to Lystra and Iconium. For a second time he travelled via Laodicia Combusta, Tyriaeum and Philomelium. At all places, he strengthened the disciples. These visits must have had a considerable impact.

3. THE CHRISTIAN USE OF THE NAME "PAUL" IN LYCAONIA IN THE 3RD AND 4TH CENTURIES51

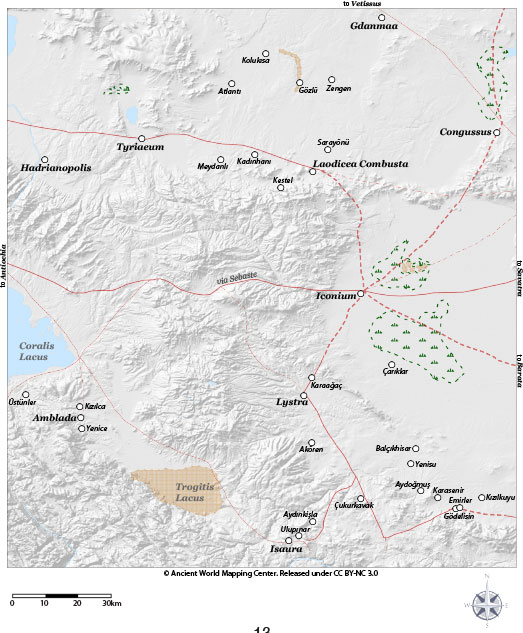

From the 3rd to the 5th centuries C.E., the name Παῦλος became by far the most used male name in funerary inscriptions from the Lycaonian region.52 Nowhere else in the world of early Christianity the name Παῦλος was used with such a high frequency as in those regions where the apostles Barnabas and Paul founded the first congregations: in the south of the province of Galatia (Iconium and Lystra) and in the Phrygian-Galatian borderland,53 areas which Paul, Silas and Timothy visited again on his second (Acts 16:1-6), and Paul, Timothy and Titus on the third missionary journey (Acts 18:23; 19:1). The name Paul became popular where the apostle Paul exerted influence in the first century. At the 5th century's council of Chalcedon, for instance, Derbe was represented by Paul, the bishop of Derbe (Destephen 2008:772-773). The epigraphical evidence from the first four centuries might be even more proving. When one maps the locations where the name Paul has been found on inscriptions, with the exception of a late example from Barata, only the south eastern rim and eastern edge of the Lycaonian plain lack evidence (cf. the map below). This Wirkungsgeschichte of the name Paul is best explained by the initial influence of the apostle himself. The evidence weakens the case of the north Galatian hypothesis considerably, according to which Paul and Silas would have gone from Iconium to Galatia proper, and would not have visited Laodicea Combusta, Tyriaeum and Philomelium. Then it becomes more difficult to explain the high frequency of the name Paul.

4. CONCLUSION

Anyone who would like to argue the case of the north Galatian hypothesis, should take note of the epigraphical evidence, too. It is rather unconvincing to argue that Paul did not have any success in Galatia, because one does not hear of any significant Christian communities in northern Galatia (Galatia proper) until the 4th century. It is fatal to construct the history of primitive Christianity in the 1st century when turning a blind eye to later evidence from the 2nd and the 3rd centuries. I had to confine myself referring to the epigraphical evidence. The literary evidence will enhance these findings.

What happened to the Galatian Christians? They have flourished in Lycaonia up until the Arabian conquest.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

For abbreviations of epigraphic editions used in this article, cf. the list of "Bibliographic Abbreviations" in Brill's New Pauly (http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/brill-s-new-pauly/bibliographic-abbreviations-Bibliographic_Abbreviations). [ Links ]

Ameling, W. 2004. Kleinasien. Vol. 2 Inscriptiones Judaicae Orientis. Tübingen: Mohr. [ Links ]

Ballance, M. 1957. The site of Derbe: A new inscription. Anatolian Studies 7:147-151. [ Links ]

Barclay, J.M.G. 1996. Jews in the Mediterranean Diaspora: From Alexander to Trajan (323 BCE-117 CE). Edinburgh: T&T Clark. Hellenistic Culture and Society 33. [ Links ]

Barrett, C.K. 1998. A critical and exegetical commentary on the Acts of the Apostles. Vol. 2, Introduction and commentary on Acts XV-XXVIII. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. International Critical Commentary. [ Links ]

Blass, F. & Debrunner, A. 2001. Grammatik des neutestamentlichen Griechisch: Bearbeitet von Friedrich Rehkopf. 18th ed. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck. [ Links ]

Bloedhorn, H. et. al. 1992. Die jüdische Diaspora bis zum 7. Jahrhundert n. Chr. Map B IV 18 of Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients. Wiesbaden: Reichert. [ Links ]

Breytenbach, C. 1996. Paulus und Barnabas in der Provinz Galatien: Studien zu Apostelgeschichte 13f.; 16,6; 18,23 und den Adressaten des Galaterbriefes. Leiden: Brill. Arbeiten zur Geschichte des antiken Judentums und des Urchristentums 38. [ Links ]

Breytenbach, C. 2004. Probable reasons for Paul's unfruitful missionary attempts in Asia Minor (A note on Acts 16:6-7). In: C. Breytenbach & J. Schröter (eds.), Die Apostelgeschichte und die hellenistische Geschichtsschreibung: Festschrift für Eckhard Plümacher zu seinem 65. Geburtstag (Leiden: Brill, Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity 57), pp. 157-69. [ Links ]

Breytenbach, C. 2013. What's in the name 'Paul'? On early Christian inscriptions from Lycaonia. In: P.-G. Klumbies & D. du Toit (eds.), Paulus - Werk und Wirkung. Festschrift für Andreas Lindemann zum 70 Geburtstag. (Tübingen: Mohr), pp. 463-477. [ Links ]

Breytenbach, C. & Zimmermann, C. Forthcoming. Early Christianity in Lycaonia and adjacent areas. Leiden: Brill. Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity/Early Christianity in Asia Minor. [ Links ]

Conzelmann, H. 1972. Die Apostelgeschichte. 2nd ed. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck. Handbuch zum Neuen Testament 7. [ Links ]

Danker, F.W. 2000. A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament an other early Christian literature: Based on Walter Bauer's Griechisch-deutsches Wörterbuch zu den Schriften des Neuen Testaments. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Darbyshire, G. Mitchell, s. & Vardar, L. 2000. The Galatian settlement in Asia Minor. Anatolian Studies 50:75-97. [ Links ]

Destephen, S. 2008. Prosopographie du diocese d'Asie. Vol. 3 of Prosopographie chrétienne du Bas-Empire. Paris: Association des amis du centre d'histoire et civilisation de Byzance. [ Links ]

Dibelius, M. 1968. Aufsätze zur Apostelgeschichte. 5th ed. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck. Forschungen zur Religion und Literatur des Alten und Neuen Testaments 42. [ Links ]

Freeman, P. 2001. The Galatian language: A comprehensive survey of the language of the ancient Celts in Greco-Roman Asia Minor. Lewiston: Mellen Press. [ Links ]

French, D. 1994. Acts and the Roman Roads of Asia Minor. In: D.W.J. Gill & C. Gempf (eds.), The Book of Acts in its first century setting. Vol. 2: The Book of Acts in its Graeco Roman Setting (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans), pp. 49-58. [ Links ]

Haenchen, E. 1965. Die Apostelgeschichte. 5th ed. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck. Kritischexegetischer Kommentar über das Neue Testament 3. [ Links ]

Halfmann, H. 1979. Die Senatoren aus dem östlichen Teil des Imperium Romanum bis zum Ende des 2. Jahrhunderts n. Chr. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck. Hypomnemata 58. [ Links ]

Hemer, C.J. 1975. Alexandria Troas. Tyndale Bulletin 26:79-92. [ Links ]

Horsley, G.H.R. 1987. New documents illustrating early Christianity: A review of the Greek inscriptions and papyri published in 1979. Vol. 4. North Ryde: Ancient History Documentary Research Centre, Macquarie University. [ Links ]

Huttner, U. 2013. Early Christianity in the Lycus Valley. Leiden: Brill. Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity 85/Early Christianity in Asia Minor 1. [ Links ]

Jervell, J. 1998. Die Apostelgeschichte. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck. Kritisch-exegetischer Kommentar über das Neue Testament 3. [ Links ]

Lee, G.M. 1970. The aorist participle of subsequent action (Acts 16:6). Biblica 51:235-237. [ Links ]

Lee, G.M. 1975. The past participle of subsequent action. Novum Testamentum 17:199. [ Links ]

Levick, B. 1967. Roman colonies in southern Asia Minor. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Mason, S. 1974. Greek terms for Roman institutions: A lexicon and analysis. Toronto: Hakkert. American Studies in Papyrologie 13. [ Links ]

Mitchell, S. 1993. Anatolia: Land, men and gods in Asia Minor. Vol. 1: The Celts in Anatolia and the impact of Roman rule. Vol. 2: The rise of the church. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Öhler, M. 2003. Barnabas: Die historische Person und ihre Rezeption in der Apostelgeschichte. Tübingen: Mohr. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 156. [ Links ]

Pesch, R. 1986. Die Apostelgeschichte. Vol. 2: Apg 13-28. Neukirchen-Vluyn/Zurich: Neukirchener/Benziger. Evangelisch-Katholischer Kommentar zum Neuen Testament 5,2. [ Links ]

Pouilloux, J. Roesch, P. & Marcillet-Jaubert, J.M. 1987. Testimonia Salaminia: Corpus épigraphique. Vol. 13 of Salamine de Chypre. Paris: De Boccard. [ Links ]

Ramsay, W. 1897. The cities and bishoprics of Phrygia: Being an essay of the local history of Phrygia from the earliest times to the Türkish conquest. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Robertson, A.T. 1931. A grammar of the Greek New Testament in the light of historical research. 5th ed. New York: Hodder & Stoughton. [ Links ]

Roloff, J. 1981. Die Apostelgeschichte. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck. Neues Testament Deutsch 5. [ Links ]

Sänger, D. 2010. Die Adresse des Galaterbriefs: Neue(?) Überlegungen zu einem alten Problem. In: M. Bachmann & B. Kollmann (eds.), Umstrittener Galaterbrief: Studien zur Situierung und zur Theologie des Paulus-Schreibens (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, Biblisch-theologische Studien 106), pp. 1-56. [ Links ]

Schmithals, W. 1982. Die Apostelgeschichte des Lukas. Zurich: Theologischer Verlag. Zürcher Bibelkommentare 3,2. [ Links ]

Schneider, G. 1982. Die Apostelgeschichte. Vol. 2: Kommentar zu Kap. 9,1-28,31. Freiburg: Herder. Herders Theologischer Kommentar zum Neuen Testament 5,2. [ Links ]

Schürer, E. 1986. The history of the Jewish people in the age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C.-A.D. 135). Vol. 3,1. Rev. ed. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. [ Links ]

Spicq, O. 1994. Theological lexicon of the New Testament. 3 vols. Peabody: Hendrickson. [ Links ]

Talbert, R.J.A. 2000. Barrington atlas of the Greek and Roman world. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Trebilco, P. 1991. Jewish communities in Asia Minor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Society for New Testament Studies Manuscript Series 69. [ Links ]

Weiser, A. 1985. Die Apostelgeschichte. Vol. 2: Kapitel 13-28. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus. Ökumenischer Taschenbuchkommentar 5,2. [ Links ]

Zerwiok, M. 1963. Biblical Greek: Illustrated by examples. Rom: Pontifical Biblical Institute. [ Links ]

1 Cf. Acts 13-14. For an historical critical and literary analysis, cf. Breytenbach (1996: Teil B).

2 Cf. Breytenbach and Zimmermann, forthcoming. This essay uses material from this publication.

3 For more detail, cf. Sänger (2010); Breytenbach (1996:99-112).

4 Cf. Pausanias 1.3.5; 10.3.4; Strabo 2.2.8 (146); 4.1.1 (176); 4.2.1 (189); 7.2.2 (293); Appian, Syria 32 (163); Iberia 1; Sib. Or. 3:509; 1 Macc 8:2; IK 15 no. 1558; IK 23 no. 75; IG 12,2 no. 516; MDAI(A) 37 (1912), 294 no. 20; SB 3 no. 7238. For abbreviations of epigraphic editions used in this essay, cf. the list of "Bibliographic Abbreviations" in Brill's New Pauly (http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/brill-s-new-pauly/bibliographic-abbreviations-Bibliographic_Abbreviations).

5 E.g., in Caria (I8 no. 275), the Troad (Pfuhl/Möbius no. 1213), Mysia (IK 18 no. 125), and Lycia (TA no. 251).

6 Cf. for Pisidia TAM 3 no. 246 (Termessos); SEG 2 no. 710 (Pednelissos); SEG 19 no. 840 (Pogla); for Lycaonia CIG nos. 3991 and 400 (both Iconium), MAMA 4 no. 197 (Apollonia), for Phrygia JRS 2 (1912), 253 no. 8). Cf. also Mitchell (1993:1:31-41, 57).

7 Cf. Mitchell (1993:1:53, 55, 57). I am indebted to Freeman (2001:23-77) for the names in the following list.

8 Cf. MAMA 7 no. 401 (Κοµιν α).

α).

9 Cf. MAMA 7 no. 532 (Κονβατια ος).

ος).

10 Cf. SEG 1 no. 463 ('Επατόριξ).

11 Cf. MAMA 1 no. 93a (Καµµα).

12 Cf. JHS 22 (1902), 123 nos. 55 (Έβουρηνός) and 56 ([Έβ]ουρηνά).

13 Cf. ETAM 15 no. 207 (Κορτερίς).

14 Cf. ETAM 15 no. 232 (Ρηγεῖνος and Μεδούσας).

15 Cf. ETAM 15 no. 214 (Τρο ονδας).

ονδας).

16 Cf. ETAM 15 no. 361 (τρο ονδας).

ονδας).

17 Cf. SEG 34 no. 1400 (Κα[µ]µάνιον).

18 Cf. ETAM 15 no. 85 (Μουσιανός).

19 Cf. ETAM 15 no. 140 (Αὐρισ ός).

ός).

20 Cf. TAM 3 no. 929 (Τρω ονδος)

ονδος)

21 Cf. IK 61 no. 454 (Και ιλλία).

ιλλία).

22 Cf. CIL 6 no. 31545 (Breytenbach 1996:180, facsimile); Mitchell (1993:2:7).

23 Cf. SEG 20 no. 302 (Breytenbach 1996:181-82, photo).

24 It is unlikely that a city bearing the king's name would not be under the important Phrygian cities mentioned by Josephus as one of the cities where Jews were settled (Antiquitates Judaicae 12.147-153). Antioch was on the border between Phyrgia and Pisidia. Acts 13:14 and 42 mention a synagogue.

25 The expression χώρα denotes either land or an administrative region of a city, or - like here - the territorium of the colony; cf. TAM 3 no. 2; also Mason (1974: s.v.) The soft hills between the natural triangle formed by the Sultan Daglari stretching diagonally from the east northwestwards, the Karakus Dagi from the west northeastwards and the Dedegöl Daglari in the south, shape the territory of ancient Antioch. It included an area of almost 1 400 km2, from modern Körküler in the northwest, Hüyüklü in the southwest, Gelendost (Dabenae) in the south-southwest to Sarkikaraağaç (Neapolis) in the south-southeast (cf. Levick 1967:44-45).

26 Cf. Mason (1974: s.v.). On the governance of the colony, cf. Levick (1967:79); Mitchell (1993:1:89-90).

27 For this sense of ἐ βάλλω, cf. Danker (2000: s.v.) The personal pronoun in τῶν όρίων αὐτῶν refers to back to τοὺς πρώτους τῆς πόλεως. The subject of ἐ

βάλλω, cf. Danker (2000: s.v.) The personal pronoun in τῶν όρίων αὐτῶν refers to back to τοὺς πρώτους τῆς πόλεως. The subject of ἐ έβαλον is thus those in charge of the colony. They had the power to expel from the territory.

έβαλον is thus those in charge of the colony. They had the power to expel from the territory.

28 Lystra's domain stretched in the west to the Erenler Daglari and in the south up to the banks of the Car§amba river (cf. Levick 1967:53-54).

29 Due to the topic under discussion in this essay, material published previously was abbreviated and restructured to fit the current argument in this updated version (cf. Breytenbach 2004:157-169).

30 On φρυγία as an adjective, cf. Horsley (1987:174).

31 It is thus unnecessary to explain why γαλατικήν χώραν lacks an article, pace Conzelmann (1972:97); cf. the discussion by Barrett (1998:766-68).

32 Cf. Lee (1970; 1975). Note the early critique on such a reading by Robertson (1931:632-33).

33 This latter reading seems to fit the general narrative strategy of the episode better. Paul and his company were directed towards Troas to reach Macedonia as quickly as possible (cf. Dibelius 1968:12, 69, 169). It is nowhere implied that Paul and his company spread the Gospel on this journey through the Phrygian and Galatian regions. Even Haenchen (1965:427) explicitly notes this, although his adherence to the North-Galatian hypothesis forces him to make an exception in the case of the Galatian region. Neither was there a deviation down the Lycus or Meander valleys into Asia, nor did they cross the Sündiken Daglari into Bithynia. The possible road led down the Tembris until Dorylaeum and then carried on to Troas (cf. French 1994:54).

34 This would exclude a journey into Galatia proper.

35 On this road, cf. Mitchell (1993:1:40-41).

36 Cf. French (1994). For detailed topographical maps of the Lycus and Meander valleys, see Talbert (2000:61 and 65).

37 It is not necessary to add Antioch ad Pisidiam (Yalvaç), but see Haenchen (1965:419); Schneider (1982:201, 202-04); Weiser (1985:402).

38 Here there must have been a synagogue; cf. MAMA 4 no. 90 (= Ameling 2004 no. 214).

39 Cf. Pesch (1986:101); Roloff (1981:241); Jervell (1998:416).

40 Judging Luke's motives, Schmithals (1982:147) comments that Paul is depicted to avoid the centers of later Christian heresy (cf., e.g., Marcion and 2 Tim. 1:15).

41 For cartographic overviews, cf. Bloedhorn et al. (1992:B VI 18); Mitchell (1993:2:42) and 52. From Acmonia there is evidence of a 1st century synagogue; cf. Ameling (2004 no. 168) (=MAMA 4 no. 264); Mitchell (1993:2:33-36).

42 Cf. Ameling (2004 no. 180) (=MAMA 4 no. 202); Mitchell (1993:2:35).

43 Previous summaries of the evidence by Schürer (1986:27-30), Trebilco (1991:85-103), Mitchell (1993:2:33-34), and Barclay (1996:259-281). Cf. also Ameling's introduction (2004:380-382), and the 3rd century inscription published by Ameling (2004: no. 179).

44 In Laodicea a Roman Iudex, Lucius Pedecaeus, registered the amount. In Apamea, a Roman, Sextius Caesius, weighed a little less than a hundred Roman pounds in the presence of the Praetor; cf. Cicero, Pro Flacco 28.67f.

45 For later (2nd-4th centuries C.E.) Jewish inscriptions from Laodicea, cf. Ameling (2004: nos. 212, 213).

46 Cf. Ameling (2004: nos. 189, 190, 192, 195, and 205-206 [2nd century C.E.], 191 and 201-204 [2nd-3rd], 187, 196-200, and 207-209 [3rd], 188 [3rd-4th], 194 [4th]). The late evidence implies an established community, cf. also Eusebius, Historia ecclesiastica 4.27.1.

47 Here Philo, Legatio ad Gaium 315, mentions the assembly of the Jews.

48 For Magnesia, cf. Ign. Magn. 8:1; for Tralles, cf. Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae 14.242; for Antiochia ad Meandrum, cf. MAMA 4 no. 202 (late 2nd century C.E.?); for Laodicea ad Lycum, Hierapolis, and Colossae, cf. Huttner (2013).

49 Cf. Ramsay (1897:667-676); Schürer (1986:27-32); Trebilco (1991:58-103); Mitchell (1993:2:33-35).

50 For this argument, cf. Breytenbach (2004:163-164).

51 This section summarizes an argument developed by Breytenbach (2013).

52 The name Βαρνάβας is mentioned only once in Salamis, the eastern port of Cyprus. Cf. Pouilloux, Roesch and Marcillet-Jaubert (1987: no. 238C1); cf. also the mosaic from an early Byzantine church floor in Thrace (SEG 40 no. 887). On Barnabas, cf. Ohler (2003).

53 There is also 3rd century evidence on the road westwards. Cf. MAMA 7 no. 297 (Amorium); SEG 28 no. 1210 (Synnada).