Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.33 n.1 Bloemfontein Jan. 2013

W.P. Wahl

Research associate, Office of the Dean, Faculty of Theology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. E-mail: wahlwp@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

During the past five decades the heartland of global Christianity has shifted to the Southern hemisphere. This places the responsibility of future Christianity predominantly in the hands of church leaders in these regions. It is therefore crucial to critically reflect on how effective theological education is to produce competent church leaders, especially in Africa. This article aims to give an overview of the challenges theological education in Africa is currently facing, and then to provide a macro vision of the major moments in the development of the international discourse on theological education over the past five decades. This comparison will inform practitioners about the relevance of current models used for theological education in Africa. By highlighting the relevance of these various models and how they relate to challenges in Africa, this article contributes to research on the development of new and alternative frameworks for theological education in an African context.

Keywords: Theological education, African context, Contextualised theological education, Ecumenical theological education

Trefwoorde: Teologiese opleiding, Afrika konteks, Gekontekstualiseerde teologiese opleiding, Ekumeniese teologiese opleiding

1. INTRODUCTION

Since Niebuhr (1950) initiated the modern discourse on theological education, many scholars2 have made valuable contributions from various perspectives. Consequently a number of existing models for theological education emerged over the past five decades. But in which ways do these existing models contribute toward relevant theological education for today?

Gerloff (2009), Jenkins (2002:2-3), and Walls (2002:220) all underline the changing context of global Christianity when they argue that the heartland of global Christianity has shifted from the Northern hemisphere to the Southern hemisphere during the past 50 years. At the beginning of the 21st century Africa, together with Latin America and some parts of Asia, accommodated more than half of all the Christian believers in the world, and if this trend continues, a projected two-thirds of Christians will live in these countries at the end of this century (Gerloff 2009; Jenkins 2002:2-3; Walls 2002:220). "There can be no doubt that the emerging Christian world will be anchored in the Southern continents" (Jenkins 2002:14).

But this geographical shift also implies a cultural shift; i.e. a change in the thought processes, theology and religious practices of Christianity (Gerloff 2009; Jenkins 2002:6-8; Walls 2002:220). While the church in Europe and North America is adjusting itself to the liberal orthodoxies of Western secularism, mainstream Christianity in the South remains traditionalist, orthodox, and supernatural (Jenkins 2002:8-9). However, these thought processes and religious practices of the church in the South have not yet matched proportionately the geographical shift that has taken place (Walls 2002:220). For this cultural shift to happen, proper interaction between Christianity and the cultures of Africa, Asia, and Latin America is needed (Walls 2002:220). If the quality of this interaction is good, it will produce within these continents creative theological development, mature ethical thinking and a deep authentic response to the Gospel on a personal and a cultural level (Walls 2002:221). However, if this interaction is poor, Christianity will produce deformation, bewilderment, doubt, and insincerity on a worldwide scale (Walls 2002:220-221). It is therefore crucial that the church in the South has leaders that are competent to lead the church to this required level of maturity.

This need for competent church leaders, especially in Africa, is emphasised by Chitando (2009), Gatwa (2009), Mwesigwa (2009), Naidoo (2008:128), Walls (2002:220-221), and Werner (2008:86-87). These scholars argue that a new and alternative framework for theological education in Africa is needed; something that will produce church leaders that are competent to meet the contextual challenges of this continent (Chitando 2009; Houston 2009; Gatwa 2009; Mwesigwa 2009; Swanepoel 2009; Werner 2009). In the same vein, Gerloff (2009:17) also identifies that "fresh educational tools" are needed to equip church leadership in Africa.

Thus, the change in global Christianity brought about a need to assess the effectiveness of theological education today. Theological education in Africa is currently facing a number of challenges and those tasked to develop its curricula, programmes, institutions and methodologies are compelled to critically reflect on the relevance of the models used.

The aim of this article is to give an overview of the challenges theological education in Africa is currently facing, and to provide a macro vision of the major moments in the development of the international discourse on theological education over the past five decades. This will enable practitioners to make informed decisions about what is relevant for theological education in the African context today.

This article does not include all the detail and all the authors that have contributed to the discourse on theological education. However, it purposefully focuses on the broad movements in the development of the discourse on theological education. The discourse on theological education will be analysed from the theological education movements of the World Council of Churches (WCC) in the 1950's, up to the debate on theological education as presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology held at the University of Stellenbosch (South Africa) during June 2009. The same conference was held from 18 to 22 June 2012 at the School of Theology, University of Kwazulu Natal, during which various papers were delivered on the topic of theological training in Africa (Theological Society of South Africa 2012)3.

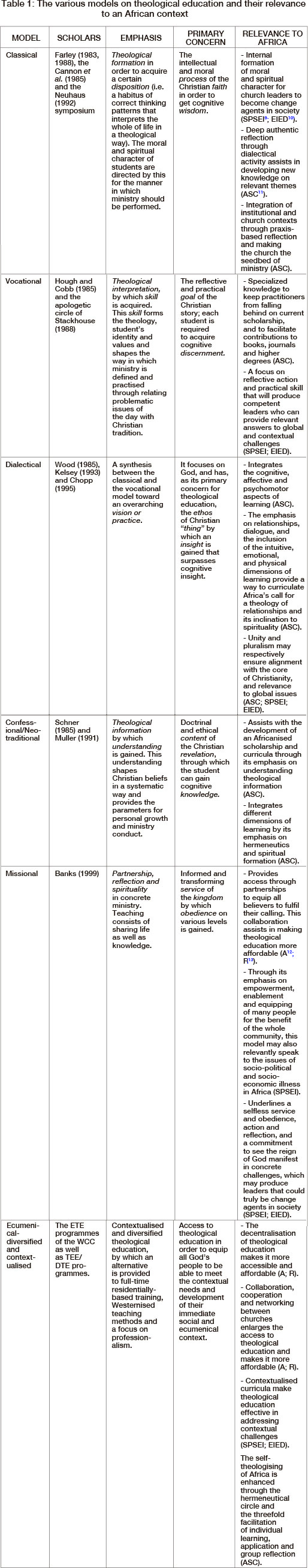

The information about the discourse on theological education is not presented chronologically, but rather in different categories. The following categories are found in the international literature: the classical model; vocational model; dialectical model; neo-traditional model; missional model; and ecumenical-diversified model. These categories provide a useful way to structure the vast field of literature that has been generated through the discourse on theological education, and can serve as a starting point to build and expand upon in later studies.

2. THE AFRICAN CONTEXT

Theological education in the African context is currently facing a number of challenges. Chitando (2009), Houston (2009), Gatwa (2009), Kinsle (2008a:8-11), Mwesigwa (2009), Swanepoel (2009), and Werner (2009) identify the following four categories that present themselves as challenges for theological education in African: access; the lack of resources; sociopolitical and social-economic illness; and an Africanised scholarship and curricula. Kinsler (2008a:7-8) adds to this list two global challenges of the twenty-first century, namely: economic injustice and ecological destruction. It is against these contextual challenges that the relevance of existing models for theological education must be tested.

2.1 Access

Access to theological education remains a challenge within the African context. On the one hand there are a vast number of church leaders without any theological education, and on the other hand there is a huge need to equip part-time ministers and church members in order to fulfil their individual callings. Houston (2009) argues that 80% of African pastors are insufficiently trained. Werner (2009), head of the African programme on Ecumenical Theological Education (ETE) of the World Council of Churches (WCC), mentions that a specific section in the church needing special attention is the African Independent Churches (AIC). He argues for the development of a new form of theological education; a form that is attractive and accessible to the majority of these leaders who are without any theological training (Werner 2009). Almost 50% of all church leaders in South Africa belong to AIC and that the majority of them have no form of theological education (Swanepoel 2009). One of the reasons for this situation is that these churches were not recognised in the past as authentic Christian churches (Swanepoel 2009). In the same vein Mwesigwa (2009) identifies ethnic biases and discrimination through the religious education system as an obstacle in Africa towards proper access to theological education.

The need to equip part-time ministers and church members in order to fulfil their individual calling opens up a new dimension in access to theological education. Amanze (2009) makes a case for theological education that is open and accessible to equip all believers to establish the Kingdom of God in this world. Swanepoel (2009) also argues that traditional methods of theological education are insufficient to equip parttime ministers and focused ministries like those operating in the fields of children's church and correctional services. Consequently Swanepoel (2009) suggests better collaboration, cooperation and networking between institutions in Africa in order to address the need for theological education on academic levels lower than universities' training. Both the shortage of trained ministers as well as the opportunity of church members to get trained in their individual calling might be addressed through Kinsler's (2008a:8-11) nine interrelated dimensions to provide better access to theological education in Africa. These are: geographical access; economical access; cultural access; ecclesiastical access; gender access; race access; class access; different abilities access; pedagogical access. This means that access to theological education should bridge the divisions that historically separated those who had access from those who were denied access.

The challenge of access to theological education is magnified by the great need in Africa for the training of church leaders. This implies that access to ministry training should not be limited to full-time ministers but should be expanded to include part-time ministers and church members.

2.2 The lack of resources

One of the biggest challenges towards providing access to theological education in Africa is the lack of proper resources (Chitando 2009). Training often takes place amidst poverty, wars, economic chaos, digital divide and erratic electricity (Houston 2009). Gatwa (2009) argues that the shortage in proper library facilities and trained personnel challenges the provision of the needed theological education in Africa.

Houston (2009), however, makes a case for self-sustainability and in this steers away from models that make theological institutions in Africa dependent on outside resources. Chitando (2009) also underlines the need for strategies through which enough resources can be generated to meet operational needs. Practical examples of entrepreneurial initiatives are: building houses and offices on the premises of theological institutions in order to generate a rental income; starting a Cyber-café; starting a primary/ secondary school; and planting bananas on their premises (Houston 2009). Houston (2009) also argues that the full-time residential-based system of theological education is costly and that a great need exists for alternative ways of theological education where students can stay within their own town/city and in such a way cut accommodation and other related costs.

Thus, theological education institutions in Africa often lack the necessary resources needed to provide good training. However, institutions should become self-sustainable through entrepreneurial efforts and alternative modes of teaching. This lack of resources is primarily a result of the sociopolitical and social-economic problems in Africa; a challenge theological education needs to address.

2.3 Socio-political and socio-economic illness

Chitando (2009), Gatwa (2009), Houston (2009), Mwesigwa (2009), and Swanepoel (2009) have identified some of the areas where socio-economic change in Africa is needed, namely: the HIV and AIDS pandemic (and the resulting number of orphans); ethnic conflict and wars; the abuse of children; family malfunction; political instability; poverty; and economic chaos. Kinsler (2008a:50-51) more specifically outlines the context of contemporary South Africa in this regard. These socio-economic and socio-political challenges of Africa become even more problematic when it is considered that Christianity is the fastest-growing faith in Africa and that Africa is, at large, responsible for the current re-evangelisation of Europe (Gatwa 2009) due to the African Diaspora (Werner 2009). Without taking responsibility for her own domestic needs, the church in Africa will lose her credibility.

Mwaura (2009) is thus correct when he identifies the need for properly-trained leaders who are change agents in society. Werner (2008:86) also identifies leadership as one of the crucial competencies theological education needs to establish. Werner (2008:86) emphasises a competence of leadership which

empowers rather than controls the manifold gifts of a given Christian community and helps to enable, equip and discern these gifts and charismata for the benefit of both the up building [of] the local congregation (oikodome) as well as peace and justice for the whole of the human community.

Thus, the socio-political and socio-economic difficulties of Africa are a challenge for theological education to address in order to protect the credibility of the church in Africa.

2.4 An Africanised scholarship and curricula

Houston (2009) values the self-theologising of Africa to be important. What he thereby means is that theological institutions in Africa need to see themselves as teaching institutions that are closely linked to the context of their local faith community; institutions that are not falling behind on current scholarship but are actively contributing to it through books, journals and higher degrees.

Houston (2009) and Walls (2002:222-226) emphasise that African theological curricula is often Western in its content and mode of delivery. In this they make a case for accredited and accessible competence-based curricula relevant to the African context. Relevance is also valued by

Gatwa (2009) who argues that theological education must resource the life of the people, and in this theological institutions stand accountable to the church. In the same vein Swanepoel (2009) identifies a gap between the needs of the people in the church and the content taught in theological institutions; curricula need to become relevant. Chitando (2009) also makes a case for accredited theological curricula in Africa and identifies the following relevant themes to be addressed: HIV and AIDS; political literacy; and masculinity.

The relevance of theological curricula is further problematised by Werner (2009) who argues that the emergence and ongoing growth of Charismatic/Pentecostal churches in Africa gives rise to a different student population with different needs. Werner (2009) makes the challenge of relevant theological education even more nuanced by asking what effect the African diaspora has on the theological curricula being taught.

However, Amanze (2009) argues that relevance in an Africanised theology can not only be theoretical, it should be action-oriented. Gatwa (2009) calls for competence-based curricula and makes the application thereof even more practical by emphasising the need for proper mentorship in theological education.

The Africanisation of theological education thus hinges on the relevance of the themes in its curricula, its focus on competence, as well as on the unique contribution it should make to the scholarship of theology as a whole.

2.5 Global challenges: Economic injustice and ecological destruction

Kinsler (2008a:7-8) argues that theological education must address, through diverse and contextualised approaches, two global challenges of the twenty-first century, namely: economic injustice and ecological destruction. Consequently Kinsler (2008a:25) proposes a "theological-biblical-ministerial formation with a Sabbath-Jubilee perspective" to equip people at grass roots levels with "the basic tools, skills and concepts" to fulfil their calling.

Thus, access, the lack of resources, socio-political and social-economic illness, an Africanised scholarship and curricula, and economic injustice and ecological destruction present themselves as the challenges to relevant theological education in an African context. The following section will reflect on the relevance of models that emerged out of the discourse on theological education during the past five decades.

3. THE DISCOURSE ON THEOLOGICAL EDUCATION

The discourse on theological education is presented within the following categories: the classical model; vocational model; dialectical model; neo-traditional model; missional model; and ecumenical-diversified model. These categories are used to arrange the literature, generated throughout the discourse on theological education, in a logical way.

3.1 Classical model4

The classical model for theological education is developed by Farley (1983, 1988), the Collectives (Cannon, Harrison, Heyward, Isasi-Diaz, Johnson, Pellauer & Richardson 1985) and the Neuhaus (1992) symposium. Its main emphasis is theological formation by which a certain disposition is acquired (Banks 1999:143). This disposition allows thinking about the whole of life in a theological way, which, in itself, forms the moral and spiritual character of the student and provides direction for the manner in which ministry should be performed (Banks 1999:143). Theological education in the classical model is primarily concerned with the intellectual and moral process of the Christian faith in order to get cognitive wisdom (Banks 1999:143).

Through paideia (personal theological formation), Farley (1983; 1988) envisions theologia (theological wisdom that displays the correct habits of the intellect) as the unifying factor in the fragmentation of theological education. Theologia is both a disposition of the soul or habitus, as well as a logical reasoning of faith (i.e. dialectical activity) as it responds to the outside world in which it exists (Farley 1983:170, 197). Farley (1983; 1988) suggests a bigger focus on praxis and intuition, while making it relevant and accessible to all believers.

The Neuhaus (1992) conference identified moral and spiritual formation as priorities in theological education. Campbell (1992:1-21), Greer (1992:22-55), Brooks Holifield (1992:56-78), O'Malley (1992:79-111), and Strege (1992:112-131) each analyse a different aspect of a morality and spirituality that are exemplary both within the faith community and the broader society. Firstly, Campbell (1992:1-21) accentuates authenticity, accountability and representation. Secondly, Greer (1992:22-55) highlights the fact that the act of ordination is both for the church and society. Thirdly, Brooks Holifield (1992:56-78) underlines the importance on being exemplary in an integrated context. Fourthly, O'Malley (1992:79-111) compares experiences in moral formation within the Roman Catholic

Traditions with Protestant experiences and emphasises the traditional and contemporary forms of spiritual formation. Fifthly, Strege (1992:112-131) stresses the importance of the authority of Scripture, servitude, reflection, mediation, and the church as the seedbed of ministry.

The Mud Flower Collective (Cannon et al. 1985) makes a case for social transformation through theological education and in this values deep authentic conversation as paramount in the construction of knowledge. Praxis-based reflection, learning and developmental collaboration, and relationships are vital aspects of their teaching methodology and quest for justice; something that lies at the core of social transformation.

3.1.1 Relevance for theological education in an African context

The primary relevance of the classical model for theological education revolves around its focus on paideia; i.e. the internal formation as opposed to an external praxiology. The moral and spiritual character formed by this model as well as its focus on social transformation forms the relevant substance that could enable church leaders in Africa to become change agents by addressing socio-political and socio-economic issues, as well as economic injustice and ecological destruction. Its praxis-based reflection may make it even more relevant in this regard.

The formation of an Africanised scholarship and curricula may also be assisted by the classical model's deep authentic reflections, i.e. its dialectical activity, which is crucial for the formation of new knowledge. Reflective conversations around themes like the HIV and AIDS pandemic, political instability and ethnic conflict, poverty and corruption, to name but a few, could greatly assist with the self-theologising of Africa and would help to make theological curricula relevant to the needs of the African people.

The problem of the fragmentation of theological education, caused by the mere application of theory and the abstraction of theory from its context (Banks 1999:20; Kelsey 1993:102), may also be reversed by applying the proposed disposition and reflective conversations of the classical model to an Africanised scholarship and curricula. Concepts like praxis-based reflection and making the church the seedbed of ministry could integrate the curricula of theological institutions closely with the actual needs of the local faith community, and establish proper accountability. All of this could successfully feed into the formation of an Africanised theology.

3.2 Vocational Model5

The vocational model of Hough and Cobb (1985), as well as the apologetic circle of Stackhouse (1988) revolve around professional schooling and specialised knowledge, or Wissenschaft, in theological education (Banks 1999:20, 143; Kelsey 1993:102). It has as its main emphasis theological interpretation, by which skill is acquired (Banks 1999:143). This skill shapes the theological student's identity and values and forms the way in which ministry is defined and practised through relating problematic issues of the day with Christian tradition (Banks 1999:143). The vocational model has as its primary concern the reflective and practical goal of the Christian story and aims for each student to acquire cognitive discernment (Banks 1999:143).

Hough and Cobb (1985) identify practical theologians as the professional leadership required to discern what the true identity of the church is and how to interpret this identity correctly in order for the church to be relevant within a global context. The skill of practical theologians centres on practical Christian thinking and being reflective practitioners.

In the same vein Stackhouse (1988) focuses on truth and justice in a global context. The skill of cognitive discernment firstly focuses on orthodoxy by which fundamental truth guides effective praxis in a transcontextual way. Secondly, it focuses on a praxiology where the justice of God shows how theory and practice relate, and aligns the heart and will with that truth believed in the mind. The primary concern in the vocational model is the reflective and practical goal of the Christian story, and consequently the acquisition of discernment. In his argument about this primary concern Stackhouse (1988) leans heavily on the Aristotelian (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1094a-1140b) threefold division of human action, namely: praxis (reflective action); poiesis (imaginative representation/making); and theoria (systematic reflection). This is important because it implies, in line with the argumentation of Carr (2006:155-156), that knowledge originates in doing instead of in theory.

3.2.1 Relevance for theological education in an African context

The vocational model's focus on professional practitioners and specialised knowledge may assist greatly with the formation of an Africanised theology. This model's emphasis on Wissenschaft should ensure that practitioners do not fall behind on current scholarship and facilitate proper contributions to books, journals and higher degrees. Furthermore, the vocational model's rootedness in the Aristotelian actions of critical reflection, creative thinking and doing, as well as the notion that knowledge originates in doing instead of in theory, means that African leaders could be more informed in this regard that their Western partners. This is important especially for the development of an Africanised scholarship and curricula.

The focus on practical skill and discernment is also important in addressing the practical needs of the people in Africa and may greatly assist in addressing the socio-political and socio-economic challenges of this continent. Additionally, the emphasis on practical Christian thinking and relevance within a global context makes the vocational model conducive in producing church leaders who come up with possible solutions to the global challenges of economic injustice and ecological destruction.

3.3 Dialectical Model

The dialectical model was developed by Wood (1985), Kelsey (1993) and Chopp (1995). The main emphasis of the dialectical model is to draw on the strengths of both the classical and the vocational model in order to gain an overarching vision or practice (Banks 1999:143). This overarching vision or practice focuses on God, and subsequently allows for the personal, professional and societal dimensions of ministry to be influenced (Banks 1999:143). The dialectical model has as its primary concern the ethos of the Christian thing; a term used by Kelsey (1993:97-98, 103, 149, 190, 192, 195, 224) that refers to the essence of what Christianity truly is (Banks 1999:143). By understanding its ethos an insight is gained that surpasses cognitive insight (Banks 1999:143).

For Wood (1985:79, 87-89, 93-94), this insight is demonstrated through the ability to make sound theological judgement, which is cultivated through theological education. Theological judgement revolves around the capacity to engage in activities of vision6 and discernment7, not out of routine, but rather as a habitus of intelligence, sensitivity, and creativity (Wood 1985:79, 93-94). This habitus is not limited to skill and techniques, but is more of a character trait; it includes spiritual, and not only cognitive discernment, and is subject to lifelong development (1985:94-95).

Kelsey (1992; 1993) turns away from Wood's (1985) abstract discussion of the Christian thing by focussing on the notion of concrete divine understanding in theological education; i.e. a quest to know God more truly within the context of the local congregation (Banks 1999:50-51). In this Kelsey (1993:221-229) identifies four key issues related to theological education, namely: unity8; pluralism9; the dynamic movement between the Athens/classical model and Berlin/vocational model; and the need for new conceptualities in the debate about theological education.

The debate about theological education is given new direction by Chopp (1995:79) who moves even further away from any form of formality toward practical methods for studying real experiences. Chopp (1995:79, 90-92) values idea-forming practices, with feminist concepts like imagination, justice and dialogue as paramount to theological education. It favours practice above a set of theories, and rhetoric above objective interpretation (Banks 1999:55; Chopp 1995:82, 88, 90-92). It is pragmatic, relative and fallible (Banks 1999:55; Chopp 1995:82, 88, 90-92). This practice of theological education takes it beyond mere cognitive learning toward the intuitive, emotional, and physical dimensions of learning while having right relationships is as important as right knowledge (Banks 1999:55-56).

3.3.1 Relevance for theological education in an African context

Because the dialectical model draws on the strengths of both the classical model and vocational model, it creates a climactic relevance for theological education in an African context.

Kelsey's (1992; 1993) aim to establish concrete divine understanding, as well as Chopp's (1995) emphasis on practical methods to study real experiences, give the dialectical model for theological education a distinct focus on doing, as opposed to theory. This focus is important because it may assist, on the one hand, in finding possible solutions for the sociopolitical and socio-economic challenges in Africa, as well as the economic injustice and ecological destruction. On the other hand, the reflective practice of the dialectical model may contribute in influencing theory in order to give assistance in developing an Africanised scholarship and curricula.

Furthermore, Wood's (1985) argumentation about vision and discernment, and Kelsey's (1993) emphasis on knowing God in theological education, integrate the cognitive, affective and psychomotor aspects of theological education in an unique way, and goes beyond the one-faceted angle of the overarching internal focus of the classical model, or the overarching external focus of the vocational model. This unique combination of the cognitive, affective and psychomotor aspects of theological education may be crucial for the formulation of an Africanised scholarship and curricula. Also, Chopp's (1995) emphasis on concepts like relationships, justice and dialogue, the preference of practice and rhetoric, and the inclusion of the intuitive, emotional, and physical dimensions of learning is fundamental to the formation of an Africanised scholarship and curricula. Jenkins (2002:123) and Walls (2002:224-226) argue aptly that, contrary to a Western framework, Africans have a spiritual worldview, which acknowledges the influence that the spiritual world has on physical matter; the frontier between the natural and the supernatural is still open, and as opposed to the Western emphasis on individuality and autonomy, Africa values a sense of belonging; "the African intellectual matrix is likely to call for a theology of relationships" (Walls 2002:226).

The significance of the dialectical model is also seen in its emphasis on both unity and pluralism. In the development of an Africanised scholarship and curricula, unity in this model will ensure alignment with the core identity of Christianity, while pluralism will ensure relevance to global issues like economic injustice and ecological destruction.

3.4 Confessional (Neo-Traditional) Model

The confessional model is a neo-traditional approach by Schner (1985) and Muller (1991) towards theological education. The main emphasis of the confessional model is theological information by which understanding is gained (Banks 1999:143-144). This understanding shapes Christian beliefs in a systematic way and provides the parameters for personal growth and ministry conduct (Banks 1999:143-144). The primary concern in theological education is doctrinal and ethical content of the Christian revelation, through which the student can gain cognitive knowledge (Banks 1999:143-144).

Schner (1985) places the primary focus in theological education on ''knowing God'', and in this reworks the tradition stemming from Aquinas to open up the area of spiritual theology. Spiritual formation should be part of every aspect of seminary life where faculty forms students' lifestyles in a parental way until it reflects the inner life of the Trinity.

Muller (1991) revisits the post-reformation tradition of Calvin and in this emphasises the theological curriculum as a way to bridge the contextual gap between the seminary and the church. Hermeneutics become both the unifying factor within the theological encyclopaedia as well as the interpretive path through these disciplines toward contemporary formulation. Theological education is thus both meaningful and relevant to the church, as well as a reflection on the life of the church.

3.4.1 Relevance to theological education in an African context

Because the main emphasis of this model is on understanding theological information, its primary relevance centres on the development of an Africanised scholarship and curricula. Like with the dialectical model, although not to the same extent, the confessional model also includes, through its emphasis on spiritual formation, different dimensions of learning. Although this model focuses on the pedagogical value of hermeneutics, it might become irrelevant in an African context which values an oral tradition over a written framework.

3.5 The Missional Model

The fifth model, namely the missional model, has been developed by Banks (1999) and has as its main emphasis

theological mission, hands-on partnership in ministry based on interpreting the tradition and reflecting on practice with a strong spiritual and communal dimension (Banks 1999:144).

The primary concern of theological education in this model is informed and transforming service of the kingdom by which "cognitive, spiritual-moral, and practical obedience" are gained (Banks 1999:144).

Banks (1999:157-168) centres his argument about the nature of learning in the missional model on two complex relationships, namely: (a) the relationship between action and reflection; and (b) the relationship between theory and practice. Teaching is consequently reconceived as sharing life and knowledge together, as well as an active and a reflective practice (Banks 1999:169-181).

Seminaries establish the relationship between action and reflection by facilitating reflection on the praxis of God and the ongoing mission of the church in the world. In this reflection the fulfilment of the individual's present calling is paramount, while the loss of self in service to others leads to spiritual maturity. The relationship between theory and practice is complex and dynamic within the missional model. In this model theory is fused with practice. Divine revelation, however, plays an important part in the relationship between theory and practice.

Defining teaching in the missional model as sharing life and knowledge together means that the teacher embodies the very truth he/she teaches by sharing, not only his knowledge, but his/her whole life with the students. Teaching in the missional model is also an active and reflective practice because it revolves around authentic and contextualised conversation. The missional model is thus in essence about concreteness, collaboration, community, conversation, character, and commitment to the Kingdom of God.

3.5.1 Relevance to theological education in an African context

The relevance to theological education in an African context of the missional model revolves around its focus on collaboration and partnerships. This is significant because it enlarges the possibility of providing access to theological education for more people in Africa, which again feeds into the purpose of bringing in the reign of God. This commitment to the reign of God also opens up the notion of equipping each believer for his/her individual calling, which is paramount in providing solutions to the problem of access to theological education in Africa. Because the missional model underlines the empowerment, enablement and equipping of many people for the benefit of the whole community, this model also relevantly speaks to the issues of socio-political and socio-economic illness in Africa.

Furthermore, these issues are addressed in this model's focus on service and obedience, as well as its unique relationship between action and reflection. Challenges of poverty, political instability and economic chaos can be addressed from a commitment to see the reign of God manifest in all these matters. This is important, because it does not only provide a different perspective to these problems, but also a willingness and often selfless commitment to its cause. In this the missional model can assist in developing leaders who could truly be change agents in society.

3.6 Ecumenism and contextualisation in theological education

The model for ecumenism and contextualisation in theological education is the result of two movements, namely: the Ecumenical Theological Education (ETE) of the World Council of Churches (WCC); and Theological Education by Extension (TEE), also known as Diversified Theological Education (DTE). The main emphasis of this model is to provide contextualised and diversified theological education, and in this it moves away from fulltime residentially-based training, which is often delivered in a Western paradigm and focused on professionalism and academic credentials. The model for ecumenism and contextualised theological education has, as its primary concern, access to theological education in order to equip all God's people to be able to meet the contextual needs and development of their immediate social and ecumenical context.

The focus of equipping all God's people for the mission of the church revolves around the notion of conversion to the Reign of God, not only in a traditional pietistic and individualistic sense, but holistically, where all of life in this world submits itself to His Reign (Kinsler 2008a:7, 26). Therefore, this model is epistemologically rooted in

the belief that ministry is commended to the people of God through baptism and discipleship, not to a professional or clerical class through schooling, credentials, and ordination (Kinsler 2008a:25).

This does not mean that the model for ecumenical and contextualised theological education lacks academic credibility or that it is methodologically unsound. On the contrary, theological education is based on a solid hermeneutical circle of (a) "socio-economic analysis of the local and global context"; (b) "biblical-theological foundations for responding to that global and local context"; and (c) "pastoral or missional action in keeping with this kind of social-economic analysis and these biblical foundations" (Kinsler 2008a:26). Theological programmes often immerse this hermeneutical circle within the framework of spirituality and discipleship (Kinsler 2008a:26). In practice, diversified theological education has three components, namely: individual study of theoretical material and assignments taking place on a continuous basis; ongoing application of this theoretical knowledge in the context of the local church and/or community; and facilitated group discussion meetings on a weekly or bimonthly basis to discuss the comprehension and application of the study material (Kinsler 2008a:26).

The model for ecumenical and contextualised theological education is also supported by international networks like Study by Extension for All Nations (SEAN 2011) and the Increase Network (2011).

3.6.1 Relevance to theological education in an African context

Access to theological education for all believers is emphasised by the model for ecumenical and contextualised theological education. Because of this particular focus this model is significant in providing answers to the challenge of access to theological education in Africa. This model provides a way in which both existing church leaders and individual believers, who are called to a specific field of ministry, can get properly trained. Additionally, this model's underlying focus on collaboration, cooperation and networking amongst churches also enlarges access to theological education.

Through its focus on contextualised theological education within local church congregations of students, this model provides a more affordable alternative to the costly full-time residential model for training. This could greatly assist in addressing the challenge of a lack of resources for theological education in Africa.

Because the model for ecumenical and contextualised theological education is focused on the relevance of its curricula to the ecumenical and societal needs of the context, it also becomes very meaningful in addressing the socio-political and especially the socio-economic challenges of Africa. Its hermeneutical circle incorporates both the analysis of the contextual needs, as well as relevant action and application of addressing these needs from a Biblical perspective. This focus on analysis, alignment and application makes it very relevant in addressing challenges like, amongst others, poverty, family malfunctioning and abuse.

The challenge of developing an Africanised scholarship and curricula may also be addressed through the model for ecumenical and contextualised theological education. For the self-theologising of Africa it is crucial for institutions to stay closely linked with their own faith community, and this is something which this model facilitates effectively. It also purposefully steers away from a Western framework for theological education and in the process provides accredited, accessible and competence-based teaching. The model for ecumenical and contextualised theological education, through its hermeneutical circle and the threefold facilitation of individual theoretical studies, application, and group reflection, integrates the cognitive, affective and psychomotor dimensions of learning.

Furthermore, it also integrates the academic context with the personal context and institutional context of students. This integration is important because these contexts are constantly, simultaneously and in an infinite number of ways interacting with one another and with the student, leading to the construction of knowledge, the construction of meaning and the construction of self in society (Keeling 2004:10-16).

4. CONCLUSION

This article describes the current challenges theological education in Africa is facing, and provides a macro vision of the major moments in the development of the international discourse on theological education over the past five decades. Fundamentally it seeks to understand in which ways these existing models may contribute toward relevant theological education for today. This article finds that the various models for theological education (the classical model; vocational model; dialectical model; neo-traditional model; missional model; and ecumenical-diversified model) are relevant in different ways in relation to challenges like: access; the lack of resources; socio-political and social-economic illness; an Africanised scholarship and curricula; and global challenges of economic injustice and ecological destruction. These findings are summarised in Table 1.

It is argued that the findings of this article enable practitioners to make informed decisions about what is relevant for theological education in the African context, because it provides a useful way to structure the vast field of literature that has been generated through the discourse on theological education, and makes a comparison with current challenges faced in Africa. The change in context of global Christianity demands relevant theological education, especially in Africa, that will develop competent church leaders. It is, therefore, crucial that future studies build on the findings of this article in order to provide fresh and alternative frameworks towards relevant theological education.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ámanze, J. 2009. Globalization of theological education in African perspective. Presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, Session A12. 22-26 June 2009, University of Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Aristotle. 1962. Nicomachean Ethics. Tans. H. Rackham. Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge: Harvard University. [ Links ]

Banks, R. 1999. Reenvisioning theological education: Exploring a missional alternative to current models. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Brooks Holifield, E. 1992. Class, profession, and morality: Moral formation in American protestant seminaries, 1808-1934. In: R.J. Neuhaus (ed). Theological education and moral formation. (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans), pp. 56-78. [ Links ]

Campbell, D. 1992. Theological education and moral formation: What's Going On in Seminaries Today? In: R.J. Neuhaus (ed). Theological education and moral formation. (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans), pp. 1-21. [ Links ]

Cannon, K.G.; Harrison, B.W.; Heyward, C.; Isasi-Diaz, A.M.; Johnson, B.B.; Pellauer, M.D. & Richardson, N.D. 1985. God's fierce whimsy: Christian feminism and theological education. New York: Pilgrim. [ Links ]

Carr, W. 2006. Education without theory. British Journal of Educational Studies, 54(2):136-159. [ Links ]

Chitando, E. 2009. Equipped and ready to serve? Transforming theological and religious studies in Africa. Presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, Session A2. 22-26 June 2009, University of Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Chopp, R.S. 1995. Cultivation theological scholarship. Theological Education, XXXII(1):79-94. [ Links ]

Farley, E. 1983. Theologia: The fragmentation and unity of theological education. Philadelphia: Fortress. [ Links ]

Farley, E. 1988. The fragility of knowledge: Theological education in the church and the university. Philadelphia: Fortress. [ Links ]

Gatwa, T. 2009. Transcultural global mission: An agenda for theological education in Africa. Presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, Session A10. 22-26 June 2009, University of Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Gerloff, R. 2009. The African diaspora and the shaping of Christianity in Africa: Perspectives on religion, migration, identity, theological education and collaboration. Presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, Session A9. 22-26 June 2009, University of Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Greer, R.A. 1992. Who seeks for a spring in the mud? Reflections on the ordained ministry in the fourth century. In: R.J. Neuhaus (ed). Theological education and moral formation. (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans), pp. 22-55. [ Links ]

Hough, J.C. & Cobb, J.B. 1985. Christian identity and theological education. Chico, California: Scholars Press. [ Links ]

Houston, B. 2009. Missiological and theological perspectives on theological education in Africa: An assessment of the challenges in evangelical theological education. Presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, Session A11. 22-26 June 2009, University of Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Increase Network 2011. Increase Network [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.teenet.net [19 August 2011]. [ Links ]

Jenkins, P. 2002. The next Christendom: The coming of global Christianity. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Keeling, R.P. 2004. Learning reconsidered: A campus-wide focus on the student experience. Washington, D.C.: National Association of Student Personnel Administrators (NASPA) & American College Personnel Association (ACPA). [ Links ]

Kelsey, D.H. 1992. To understand God truly: What's theological about a theological school. Louisville, Kentucky: John Knox. [ Links ]

Kelsey, D.H. 1993. Between Athens and Berlin: The theological education debate. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Kinsler, R. 2008a. Diversified Theological Education: Equipping all God's people. Pasadena, California: William Carey International University. [ Links ]

Kinsler, R. 2008b. Relevance and importance of TEF/PTE/ETE: Vignettes from the past and possibilities for the Future. Ministerial Formation 110:10-11. [ Links ]

Muller, R.A. 1991. The study of Theology: From Biblical interpretation to contemporary formulation. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Mwaura, P. 2009. Panel discussion on theological education including Francois Swanepoel (Unisa), Ezra Chitando (University of Zimbabwe), Paul Mwaura (Kenyatta University, Kenya), Archbishop Mofokeng (AIC leader) and/or T Mushagalusa (University of Goma, Congo). Presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, Session A6. 22-26 June 2009, University of Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Mwesigwa, F. 2009. Modern religious and ethnic conflict in East Africa; Religious education curriculum review: A requisite response. Presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, Session B3. 22-26 June 2009, University of Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Naidoo, M. 2008. The call for spiritual formation in protestant theological institutions in South Africa. Acta Theologica, Supplementum 11:128-146. [ Links ]

Neuhaus, R.J. (ed.) 1992. Theological education and moral formation. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Niebuhr, H.R. 1950. The purpose of the church and its ministry: Reflections on the aims of theological education. New York: Harper & Row. In: M.W. Kohl 2001. Current trends in theological education. International Congregational Journal 1:112-126. [ Links ]

O'Malley, J.W. 1992. Spiritual formation for ministry: Some Roman Catholic traditions - The past and present. In: R.J. Neuhaus (ed). Theological education and moral formation. (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans), pp. 79-111. [ Links ]

Schner, G.P. 1985. Formation as a unifying concept in theological education. Theological Education 21(2):94-113. [ Links ]

Sean. 2011. Study by extension for all nations. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.sean.uk.net [19 August 2011]. [ Links ]

Stackhouse, M.L. 1988. Apologia: Contextualization, globalization, and mission in theological education. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Strege, M. 1992. Chasing Schleiermacher's ghost: The reform of theological education in the 1980's. In: R.J. Neuhaus (ed). Theological education and moral formation. (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans), pp. 112-131. [ Links ]

Swanepoel, F. 2009. Panel discussion on theological education including Francois Swanepoel (Unisa), Ezra Chitando (University of Zimbabwe), Paul Mwaura (Kenyatta University, Kenya), Archbishop Mofokeng (AIC leader) and/or T Mushagalusa (University of Goma, Congo). Presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, Session A6. 22-26 June 2009, University of Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Theological Society Of South Africa 2012. Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the fields of Religion and Theology. [Online]. Retrieved from: http://theologicalsocietysa.blogspot.com/2012/02/joint-conference-of-academic-societies.html [11 October 2012]. [ Links ]

Walls, A.F. 2002. Christian scholarship in Africa in the twenty-first century. Transformation 19(4):217-228. [ Links ]

Werner, D. 2008. Magna Charta on ecumenical formation in theological education in the 21st century - 10 key convictions. Ministerial Formation 110:82-88. [ Links ]

Werner, D. 2009. Viability and ecumenical perspectives for theological education in Africa: Legacy and new beginnings in ETE/WCC. Presented at the Joint Conference of Academic Societies in the Fields of Religion and Theology, Session A1. 22-26 June 2009, University of Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Wood, C.M. 1985. Vision and discernment: An orientation in theological study. Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press. [ Links ]

1 This article is based on the doctoral dissertation "Theological education in an African context: Discipleship and mediated learning experience as framework" by W.P. Wahl, University of the Free State 2011.

2 The names and scholarly works of these scholars will be discussed in section three of this article (under the heading: "The discourse on theological education").

3 Reference to these two conferences is substantiated by the fact that they remain some of the biggest and most significant recent theological conferences in Africa. The breadth and depth of topics that were presented encompass those of other smaller theological conferences.

4 Also called the Athens model of excellent theological education (Kelsey 1993:6-11).

5 Also called the Berlin model of excellent theological education (Kelsey 1993:12-19, 101).

6 Wood (1985:67-68) defines vision as the ability to understand things in their wholeness and relatedness.

7 Wood (1985:68) defines discernment as the insight to discern the particularity of things or situations; i.e. the ability to distinguish the difference and individuality of things.

8 Unity in theological education seeks to know if curricula are sufficiently aligned with what Christianity, in essence, is. It has to do with Christianity's inherent unity, its integrity and its identity (Kelsey 1993:96).

9 Pluralism in theological education seeks to know if curricula are sufficiently aligned with the pluralistic world in which Christianity has to be lived out; it has to do with Christianity's relevance within a global perspective (Kelsey 1993:96).

10 Socio-political and socio-economic illness (SPSEI)

11 Economic injustice and ecological destruction (EIED)

12 Africanised scholarship and curricula (ASC)

12 Access (A)

13 Lack of resources (R)