Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Theologica

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.33 no.1 Bloemfontein ene. 2013

An emerging grounded theory for preaching on poverty in south africa with matthew 25:31-46 as sermon text1

H.J.C. Pieterse

Department of Practical Theology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. E-mail: pietehjc@absamail.co.za

ABSTRACT

Since 2009, I am researching sermons on Matthew 25:31-46 by preachers of the Uniting Reformed Church and the Dutch Reformed Church (Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk). The sermons are collected in South Africa's eight provinces. This is an empirical-homiletic study with a grounded theory methodology. The open coding and selective coding cycles are already completed. This article presents the results of the last cycle, namely theoretical coding. The theory for practice describes the concepts which emerged from the data and shows the relationships between the concepts. This is a theory for the practice of preaching on Matthew 25:31-46 in the South African context of poverty. It has a bearing only on the qualitative analysis of the texts of the sermons on this text in Matthew, and does not address the entire process of the preaching event from the sermon text, the rhetorical and communicative process. It only covers the sermon analyses and the effects on the listeners' actions on the sermons mentioned in the sermons.

Keywords: Empirical homiletics, Grounded theory analysis, Sermons on Matthew 25:31- 46, A theory for practice of preaching on poverty

Trefwoorde: Empiriese homiletiek, "Grounded theory"-analise, Preke oor Mattheus 25:31-45, 'n Teorie vir die praktyk van prediking oor armoede

1. INTRODUCTION

Authors of publications on preaching and poverty emphasise that we have to preach about the poverty situation in the world, but there is no specific indication of how to do this. Neither could I find any empirical study of preaching and poverty in homiletic literature (cf. Pieterse 2009a). I am, therefore, addressing the problem of how to preach in the South African context of poverty in an empirical homiletic study. I have decided to take Matthew 25: 31-46 as a sermon text in order to be able to preach in the poverty situation in my country. The leading research question of this research project is: How do preachers deal with sermons on poverty with Matthew 25:31-46 as sermon text?

My project of a grounded theory analysis of sermons on Matthew 25:3146 from a sample of preachers from the Uniting Reformed Church and the Dutch Reformed Church (Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk) started in 2009. The hallmark of the methodology of grounded theory is generating theory from data collected in practice in a bottom-up process. I take my lead in this methodological approach from Glaser (1978), Charmaz (2006) and Pleizier (2010). The latter applied the method to research in empirical homiletics. The emerging theory from the data offers an interpretative portrayal of the studied field, not an exact picture of it (Charmaz 2006:10). In the grounded theory research of sermons, I follow Pleizier's method of the three cycles: an open coding analysis, a selective coding analysis and a theoretical coding analysis (Pleizier 2010:16-21, 99-100).

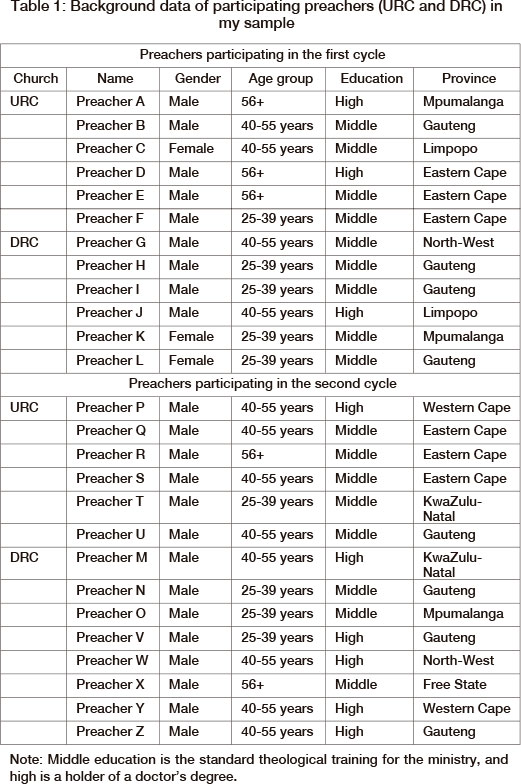

In my research of sermons with Matthew 25:31-46 as sermon text, I collected sermons from preachers of the Uniting Reformed Church (URC) and the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) in South Africa from eight provinces: 12 from the URC and 14 from the DRC, a total of 26 sermons. I have used a theoretical sample by asking my ex-doctoral students who are working in congregations in all the provinces of South Africa to identify preachers in their province so that I may approach them for a typed or written text of the sermon (cf. Swinton & Mowat 2006:69). I collected sermons and analysed them in the three cycles: the first cycle of open coding analysis of 12 sermons was completed in 2010 (cf. Pieterse 2011); the second cycle of selective coding analysis with 14 new sermons put together with the first 12 (total of 26) was completed in 2011 (cf. Pieterse 2012).

In 2012, I worked on the third cycle of theoretical coding which will end in 2013. This article presents the results of the third cycle of theoretical coding.

Homiletics forms part of practical theology. I am working within the concept of lived religion in practical theology (cf. Ganzevoort 2009). Lived religion is religious action within the action theory approach in practical theology. We work with faith as it is lived in the interrelationship between

God and human beings, and human beings with each other, in this field of my homiletic research (Immink 2005:221-226, 270-278). The field of study in this research is among preachers in the Reformed tradition. My meta-theoretical perspective (cf. Osmer 2008) is that a Reformed theologian views the Christian faith praxis as a reality where our triune God is actively working. In an empirical homiletic research of sermons, we work with empirical methodology and reflection as an integral part of the theological enterprise (Pleizier 2010:23; Van der Ven 1993:93-100). We view preaching as an event (Long 2005:22). From a Reformed perspective, preaching and listening are primary practices in which the divine-human interaction takes shape (Pleizier 2010:26).

In the following paragraphs, I will briefly describe theoretical coding, the emerging concepts from the analyses of the sermons, and an emerging theory for practice from the data.

2. THEORETICAL CODING

According to Pleizier's (2010:100) approach

The first move is from open coding to selective coding. Initially coding is very open and flexible. During selective coding, however, the researcher focuses upon more specific categories around the core variable. Abstraction increases since coding becomes more specific and less open. This move from open to selective coding takes place when the analyst is sure that she has found a core variable. The second move is from substantive to theoretical coding. Abstraction of the concepts continues to increase, for in the third cycle of coding research aims for finding the theoretical connections between the various concepts and their properties. In the first two cycles of open and selective coding, the codes and concepts are very substantive. They substantially name the processes, dimensions, aspects in the area of research ... However, in order to determine how these substantial categories relate to each other - this will be done in the third cycle of coding.

In my research, categories have emerged from the analysed sermons during the process of constant comparing and coding in the first cycle of open coding and in the second cycle of selective coding. In the first cycle, the categories in the inner world of the first 12 sermons are integrated by the core variable of appealing to the listeners of the sermon. In the second cycle of selective coding, this core variable was enriched by the notion of appealing as invitation to the listeners of the sermon to participate in the congregation's projects concerning the poor. Finally, in the process of theoretical coding, the concept of calling on the listeners of the sermons to participate in the projects of charity and empowerment emerged as a central concept, which integrated the data from the 26 sermons in the sample.

Unlike substantial codes, theoretical codes have an integrative power (Pleizier 2010:146). In grounded theory, codes such as dimensions, structures, models and types are necessary to connect substantial concepts into theoretical statements (Pleizier 2010:146). In the open coding cycle, I used the theoretical code of consequence which has revealed a clear rhetorical structure in the sermons. In the selective coding cycle, I made use of the theoretical code of type which integrates the different projects into a typology of projects practised by the congregations in my sample.

In theoretical coding, we sort the quantity of theoretical memos which the researcher has to write during the process of comparing all the sermons in the sample, comparing all the categories which have emerged, and trying out theoretical codes on the data. Sorting the theoretical memos is the final step towards abstraction. In this process, we focus on relationships between concepts. In this procedure, we compare abstract memos rather than concrete incidents and categories of the data (Pleizier 2010:147). I sorted and compared my memos in order to find the emerging concepts and the relationships between these concepts.

3. EMERGING CONCEPTS FROM THE ANALYSED DATA

The logical process in preparing and delivering a sermon is, first, the exegesis of the text chosen as a sermon text, then the sermon flowing from the exegesis with its rhetorical structure which has a relation with the text and its exegesis and, finally, in delivering the sermon, the appealing to or calling on the listeners to react to the message of the sermon. Therefore, I am presenting the three concepts which emerged from the analysis of all the sermons in the two cycles of analysis in this logical process.

3.1 Description of an exegesis of Matthew 25:31-46 as a concept

After analysing the 26 sermons, I embarked on an academic exegesis of the sermon text and used the result as a memorandum of evaluation on the sermons in order to ascertain the manner in which the preachers interpreted the text. All the preachers interpreted the meaning of the text for the sermon as a message meant for all nations and for all the poor. I did not give them any clue or directions beforehand on how to do their exegesis. This homiletic exegetical study (Immink 2010:15-16) of Matthew 25:31-46, which I did after analysing all the sermons, is meant for preachers preaching on poverty in the South African context in the Dutch Reformed Church and the Uniting Reformed Church. It forms part of my research project of a grounded theory analysis of sermons with this text as sermon text in the two churches. Therefore, I will only discuss the exegetical problems in this text for its interpretation by the preacher-exegete who has to preach it.

Matthew 25:31-46 forms part of the wider context of Chapters 23-25 in Matthew which form the fifth and last discourse of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew. Chapters 24-25 address the signs of the times, the vigilance while waiting for the parousia, the second coming of Jesus (Combrinck 1987:6970). We read Matthew as a narrative and view the parables as metaphors (Van Aarde 1994:236-240; Combrinck 1987:69; Combrinck 1991:2) - and indeed as diaphoric metaphors (Reinstorf & Van Aarde 1998:609; Pieterse 2009:16-17). The gist of these chapters is a confrontation with the demands of the kingdom of God to be vigilant while waiting for the parousia in daily living and by practising the gifts of the kingdom of God: love and mercy (Combrinck 1987:71; Jones 1995:481).

There are four outstanding problems in this text where the exegete has to make a decision on how to interpret it (Snodgrass 2008:544). I will now briefly discuss these four issues.

3.1.1 The context of the origin of the Gospel of Matthew

The majority of exegetes establish the approximate date of the origin of the Gospel of Matthew as after 70 A.D., after the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple in the Jewish war (Van Aarde 2008:544). We find this dating also with Schweizer (1978:15), Nielsen (1971:11-12) and Hill (1972:50), both of whom put it between 80 and 90 A.D. Important scholars agree on the place of the origin of this gospel. Van Aarde (2008:544) and Nielsen (1971:11) place the community in which the scribe Matthew lived in Northern Galilee and Southern Syria. Schweizer (1978:17) and Hill (1972:50) put it squarely in Syria. After the Jewish war, these new Israelite settlers were restoring rural towns in which the scribes were also active. Conflict arose between two groups of scribes, the followers of Jesus as the Messiah, and the other Israelites who still believed in a traditional view of the Messiah. The conflict focused on the interpretation of the Torah. The people (anthropoi) who followed Jesus deemed him as the one who fulfilled the Torah and the other group followed the traditional Mosaic view (Van Aarde 2008:545). In the context of the text of Matthew 25:31-46, Van Aarde (2007:417) is of the opinion

that 'the leaders' of the Matthean community tended to neglect and ignore Israelite outcasts and non-Israelites ... This state of affairs should largely be ascribed to the split in the post 70 C.E. ekklesia between 'leaders' who followed the author (and Jesus), and those who succumbed to the pressure of Pharisaic scribes.

It is important to mention Matthew's way of thinking in this process of the parting of the ekklesia and the synagogue (Van Aarde 2008:536). Eschatology in Matthew is viewed as the kingdom of heaven that has come. Matthew's eschatology "centres on the view that the final consummation of time has already begun" (Van Aarde 2008:529). Therefore, this eschatology can only be understood as an ethical eschatology (Van Aarde 2008:540; Crossan 1998:284). Matthew's eschatology functions as a continuing present perspective in which the readers are called to overcome the problems of everyday life by deeds of love and mercy (Weren 1979:190; Pieterse 2009b:17-19).

Van Aarde (2007:418-419) discusses the function of the Israelite crowd and the Gentiles in the Gospel of Matthew. This problem has to do with the relationship of Matthew 10:5-6 (the mission to Israel) and Matthew 28:19 (the mission to the whole world). According to Van Aarde (2007:416),

although the 'crowd' and the 'gentiles' do not fulfill the same character roles in the plot of the Gospel of Matthew as narrative, both groups function together as the object of both the mission of Jesus and that of the disciples in the post-paschal period.

He builds his argument, inter alia, on the concept of transparency. There is no discontinuity between the object of Jesus' mission to the Israelite crowd and the Gentiles. The commission in Matthew 28:16-20 forms the pendant of Jesus' twelve disciples to the lost sheep of Israel in Matthew 10:6 (Van Aarde 2007:419; Weren 1979:106ff.). This insight is important for the interpretation of Matthew 25:40.

3.1.2 Who are the "all the nations" in Matthew 25:32?

There are different explanations of "all the nations" (panta ta ethnè) in Matthew 25:31 who are judged by the Son of Man as King. Some exegetes, inter alia Nolland (2005:1023, 1035), are of the opinion that the passage speaks of God's judgement of Israel for their reception of missionaries. Others opine that it is the judgement of the heathen, those who have never known Christ. Christians are judged on faith that is lived out, and non-Christians are judged on the acts of love (Jeremias 1963:209). Friedrich (1977:258-259) follows Jeremias on this issue, especially that it is the judgement of the heathen.

Prominent contemporary exegetes, however, interpret this verse in a universal sense, namely all people. Donald Hagner (1995:742) reads this expression (panta ta ethnè) in the light of the same phrase in 28:19, which includes both Gentiles and Jews. This universal interpretation of 25:31 is closely related to the interpretation of the "least of these my brothers" in 25:40, 45. Van Aarde (2007:419) states that there is no convincing argument that the phrase panta ta ethnè in Matthew 28:19 refers only to non-Israelites. Snodgrass (2008:555) also interprets the "all nations" as all people who will be judged. Many scholars interpret 25:31 in this way (Weren 1979:71; Davis & Allison 1997:422-23, 428-29; Grundmann 1975:526; Via 1987:97-100; Lamprecht 1992:273-279; Van Zyl 1999:1176; Luz 2005:275).

3.1.3 Who are "the least of these my brothers" in Matthew 25:40?

Does the expression "for one of the least of these my brothers" (eni toutoon toon adelphoon mou toon elachistoon) refer to all the poor and the needy, Christian missionaries, or all Christians? (Snodgrass 2008:555). In recent years, the view that they are Jesus' own disciples has gained some acceptance (Snodgrass 2008:555). Hagner (1995:745) favours the interpretation that the

principle articulated here concerns in the first instance deeds of mercy done to disciples, brothers and sisters, and only by extrapolation to others.

Some view "the least of these my brothers" "as the Christian missionaries" (Snodgrass 2008:556).

Snodgrass approaches the problem from the viewpoint that the issue, in this instance, is the purpose of the parabolic saying and its explanation in Matthew 25:31-46.

Are they and their placement in Matthew intended to console threatened Christians . or to motivate faithful discipleship marked by mercy and love? (Snodgrass 2008:557).

He chooses the latter as the purpose, because of the context and the concerns of Jesus and Matthew. The teaching of Jesus and his gospel focuses on mercy and love. Entrance into the kingdom is based on doing the will of the Father (Mt 7:21-23). Therefore, Snodgrass (2008:557) states that "these least brothers of mine" must "be understood generally of those in need".

Van Aarde (2008:540) agrees with Weren (1979:188-190) that Matthew focuses on the ethics of care for the poorest of the poor with reference to Matthew 25:45 - the hoi elachistoi. The six works of love are ethical activities that must be practised daily in every era, with an unexpected dimension in it, because the Son of Man is in solidarity with those in need and views them as his brothers (Weren 1979:115). This is the novum in comparison with apocalyptic literature in the answer of the "when" of the paroesia and the coming of the kingdom of God (Weren 1979:115). Matthew's eschatology functions as a continuing present perspective (Weren 1979:190).

The gifts of the Kingdom of God are love and mercy, and these are universal and fundamental (Jones 1995:481). Therefore, we must practise these gifts of the Kingdom to all people in need. Hultgren (2000:320-323) interprets "these least brothers of mine" as all needy persons.2 The final difference between those who inherit the kingdom of God and those who do not, is one of ethical action (Weren 1979:181).

3.1.4 How does the judgement based on acts of love and mercy fit in with salvation based on faith in Christ? Does this text teach righteousness by means of good works?

According to Snodgrass (2008:558), this question addresses the interpretation of gar at the beginning of 25:35 and 25:42. Does the "for" in "For when I was hungry ..." point to the basis of the decision to give food, or does it indicate the evidence of redemption. However, this anxiety about salvation earned by good works is foreign to Matthew. Matthew's concern is a discipleship that is evidenced in love and mercy (Snodgrass 2008:559). Love and mercy are the criteria for the judgement of all nations (Nielsen 1974:80). These criteria are according to God's will and are the gifts of the Kingdom (Jones 1995:481). The confessing of Jesus are evident in these deeds of love and mercy (Grundmann 1975:528). God's reward (of the Kingdom) does not depend on the "measure of a man's deeds" - it remains a free gift (Schweizer 1978:480). The Gospel of Matthew stresses a practical ethics, which is meant for all people (Nielsen 1974:80). It does not intend the works of the law, but the equipment on a practical ethical level for the disciples in Matthew's community (Nielsen 1974:81).

In a homiletic study of sermons, exegesis of the sermon text is an integral part of the whole process of sermon preparation, delivery and the listeners' reaction to the sermon. Therefore, the first concept emerging from the sermons and tested by academic exegesis in this research project is the exegesis of this New Testament text as sermon text for preaching.

3.2 Description of the rhetorical structure of the sermons as a concept

The analysis of the first 12 sermons in the open coding cycle produced a clear pattern or structure in the movement of the sermon (cf. Pieterse 2011:106-110). The new sermons, which I have collected in two phases and analysed in the selective coding cycle, also show this pattern which I now phrase as a concept, namely the rhetorical structure in the sermons.

On the level of theoretical thinking, I am using theoretical codes on the material. The theoretical code of consequence suits the relationship between the categories that emerged from the analysis of the sermons. Therefore, I discovered that there is a consequence in the rhetorical appeal by the preachers in this inner world of the first 12 sermons in the data, as well as in the new sermons collected. The following pattern emerged on the question: What are the preachers doing in these sermons? Preachers are appealing to or calling on the listeners of the sermon by employing their faith participation with Jesus (1), in order to appeal to them to choose for identifying with the poor and humble as Jesus did (2), and then appealing to them for caring for the poor and humble in the present context of the congregations in South Africa (3). This rhetorical structure in the sermons, following the contours of the sermon text, puts the listeners in a situation in which they have to make a decision - either to decide not to care, or to make a decision to care, by participating in the congregational projects directed to the poor as care for them.

The second concept emerging from the sermons is the rhetorical structure of the sermons.

3.3 Description of a typology of congregational projects directed to the poor as a concept

In the second cycle of selective coding, the question is: How must we care for the poor? I asked my ex-doctoral students to identify for me preachers in congregations which have concrete projects directed to the poor. I then approached these preachers in a theoretical sample and asked for a sermon on Matthew 25:31-46 - new sermons which I have added to the first 12 sermons. In selective coding, new material must be collected in order to capture new categories of the concept of care for the poor by the congregation which emerged from the open coding cycle (Pleizier 2010:132). Properties of the categories should also be described in order to move the research in the direction of a theory for preaching on Matthew 25:31-46 in the context of poverty in South Africa. On the question: How should the congregation care for the poor?, we also have to ask: What are the categories and their properties of this type of care for the poor? New thinking on the issue of preaching on poverty is necessary, because homiletic literature in this field of preaching does not address the how question. A review of homiletic literature on the topic has shown this research gap (Pieterse 2009b:134-148). Current literature states that churches should care for the poor, but not how (Pieterse 2009b:134).

According to Holton (2007:280), selective coding

begins only after the researcher has identified a potential core variable. Subsequent data collection and coding is delimited to that which is relevant to the emerging conceptual framework (the core and those categories that relate to the core).

The potential core variable in this instance is appealing to the listeners to care for the poor by the actions of the congregation. This is related to the final appeal by the preachers from Matthew 25:31-46 in the twelve analysed sermons of the open coding cycle. Directed by the third hypothesis in the open coding analytical model, namely to care for the poor (cf. Pieterse 2011:110) as well as the potential core variable of appealing to the listeners to care for the poor by the actions of the congregation, I approached the selective coding cycle by collecting sermons from preachers working in congregations with projects to the poor. A variety of projects can now be discovered which can theoretically enrich the core variable emerging in this research. New data provide resources for finding new categories besides the categories that have been formulated in the first cycle of research in the substantive area (Pleizier 2010: 135).

Voluntary participation by church members in the action of projects for the poor by the congregation is a form of social capital. It is necessary to conceptualise social capital as it is generated in the worship service with its preaching dimension and in the voluntary actions of church members in projects by the congregation. The concept of social capital was introduced in the 1970s. One of the pioneers of research on social capital is Robert D. Putnam (2001). His findings on religion are interesting. His research has shown that religious people are very active in volunteering work - they are social capitalists. Involvement in religion is a strong predictor of voluntary work inside and outside the church. Putnam distinguishes two types of social capital, namely bonding social capital which tends to reinforce exclusive identities, and bridging social capital which tends to bring people together across diverse and social divisions (De Roest & Noordegraaf 2009:216). John Field has distinguished a third type of social capital, namely linking social capital. This implies reaching out to people outside the community (De Roest & Noordegraaf 2009:216). Three concepts in social capital come to the fore: bonding, bridging and linking. Congregations possess infrastructure as well as material and human resources that are critical components of the social capital of congregations in the process of bonding, bridging and linking (Wepener & Cilliers 2010:419).

In the dialectic tension between church members with their social capital and the poor and humble with their dignity, freedom and own responsibility as human beings, the interaction should be on an equal footing. Ricoeur views the relationship between people as a dialectical tension between givers and receivers. Not only the givers are agents who act, but the receivers are also agents who act as responsible and free people (Ricoeur 1994:291-293). In Reformed theology, the doctrine of the covenant was refined by Berkhof (1973) who regards the relationship of human beings with God as an inter-subjective relationship of love, friendship, freedom and faithfulness (Berkhof 1973:146-155). The theology of the covenant views the personal relationship with God as a relationship in which benevolence towards all human beings and responsibility can flourish. As a result of the love and grace of God in Jesus Christ towards us, the love for God and the neighbour can be practised in this relationship (Jonker 1989:198). This interpretation is in line with the emphasis of Matthew on justice and mercy towards other people.

Another notion is important for social capital by church members who voluntarily reach out in projects to the poor as a response to the sermon with its rhetorical structure, namely the question: Why are they doing it? In this instance, the theoretical concept of religious motivation is important for their actions as the motivation for them to act. Ronald Jeurissen (1993) works with religious motivation in his research on peace and religion. He refers to Auer (1977:45-46) who

contends that the function of the Christian kerygma is essentially a motivational one. The kerygma of God's creation, salvation and completion of the world motivates to moral action, by putting the Christian believer in a new context of meaning, which summons him to responsible partnership with God the Creator; which radicalizes commitment to a humane world and to the realization of a peaceable society; and which overcomes resignation and disappointment by placing human history in the perspective of its ultimate completion (Jeurissen 1993:62).

Religious motivation is thus an important motivation for church members to act in congregational projects directed to the poor. Furthermore, they are acting not in a particularistic manner, where one only cares for one's own ethnic or religious group, but in an inclusive universalism manner, where one also reaches out to people beyond one's circle (cf. Van der Ven et al. 2004:357ff., 204ff.).

A great variety of projects emerged from the sermons. I arranged the different types of projects in a typology of projects (Pieterse 2012).

Main category I: Charity projects by congregations

Subcategory IA: Provision of food

1. Congregation provides food for mineworkers when a mine does not function as a result of bad management.

Property: Provision of food for mineworkers not being paid.

2. Congregation provides food for jobless people waiting in the street for piece jobs.

Property: Provision of food for jobless people waiting to be employed.

3. Congregations provide food for poor learners at schools. Property: Provision of food for learners.

4. Congregation provides food for a poor community. Property: Provision of food for a community.

5. Congregation provides food for a home for disabled adults. Property: Provision of food for a home as institution.

6. Congregation provides food for families.

Property: Provision of food for families.

7. Congregation provides food in a squatter camp.

Property: Provision of food in a squatter camp.

8. Congregation members cultivate small vegetable gardens and bring the crop to the church where it is distributed to the poor.

Property: Vegetables grown in members of the congregation's gardens for the poor.

Subcategory IB: Provision of clothes

1. Congregation provides clothes for poor community.

Property: Provision of clothes for a community.

2. Congregation provides clothes for families in need.

Property: Provision of clothes for families.

Main category II: Projects of empowerment

Subcategory IIA: Relationships with the poor

1. Congregations form relationships of love, compassion and respect with the poor.

Property: Relationships of love, compassion and respect.

2. Congregations form relationships of mercy and care with the poor.

Property: Relationships of mercy and care.

3. Congregation forms relationships of prayer with taxi drivers and passengers during Passover.

Property: Relationships of prayer.

4. Congregation forms relationships to solve poor people's problems.

Property: Relationships of problem solving.

Subcategory IIB: Financial support

1. Congregations provide financial support for poor inhabitants of homes for the elderly.

Property: Financial support for people in homes for the elderly.

2. Congregations provide financial support for the training of pastors for poor communities.

Property: Financial support for training of pastors for poor communities.

3. Congregations provide financial support for the salaries of pastors and missionaries.

Property: Financial support for pastors and missionaries.

Subcategory IIC: Medical support

1. Congregations provide help in the preparation of medicine at state clinics.

Property: Medical support at state clinics.

2. Congregation provides voluntary nurses for sick people in congregation.

Property: Medical support for people in congregation.

Subcategory IID: Educational support

1. Congregations provide money and food for poor learners in nursery, primary and high schools.

Property: Educational support for nursery, primary and high schools.

2. Congregations provide money, clothes and food for orphans in children's homes.

Property: Educational support for orphans in children's homes.

Subcategory IIE: Building support

1. Congregations provide help in building houses in institutions of rehabilitation.

Property: Building support in institutions of rehabilitation.

2. Congregations provide helpers for the building of houses and start a vegetable garden to care for orphans.

Property: Building support in housing for orphans.

3. Congregation provides helpers in establishing a bakery and manufacturing of crafts for poor people.

Property: Building support for a bakery and crafts manufacturing.

Subcategory IIF: Self-help support

1. Congregation provides helpers for training women to sew, make blankets and necklaces to sell.

Property: Self-help training for manufacturing goods for sale.

2. Congregation provides helpers to teach women to read and write.

Property: Self-help teaching to read and write.

3. Congregation has an academy for rowing-boat and swimming skills on a dam in the vicinity for poor children with the purpose to develop self-discipline and a positive view of the self.

Property: Developing rowing-boat and swimming skills for general development of children.

4. Congregation has therapeutic professionals who work with trauma experiences and healing.

Property: Professional help in situations of trauma.

5. Congregation provides electricity generated by means of sun energy to poor residents with high school children in a squatter camp in their vicinity to help education and development.

Property: Self-help support for own educational and general development.

6. Congregation provides skills training for leadership and entrepreneurship for poor people, as well as seed money to start their own business - already eight successful businesses were up and running in 2011.

Property: Training and seed money to start own business.

The central, enriched concept which integrated all categories is now: calling on the listeners in the sermon to participate in congregational projects of charity and empowerment. These projects all take place in the immediate context of the specific congregation. Although many congregations run the same kind of projects, they do not overlap, because each one happens within the context of the vicinity of the specific congregation. These types of categories of projects by congregations in their outreach to the poor, inspired by preaching on the text from Matthew 25:31-46, bring something new into homiletic literature on preaching to the poor.

This typology of congregational projects in South Africa is the third concept emerging from the sermons.

4. A GROUNDED THEORY FOR THE PRACTICE OF PREACHING ON POVERTY IN SOUTH AFRICA FROM MATTHEW 25:31-46 AS SERMON TEXT

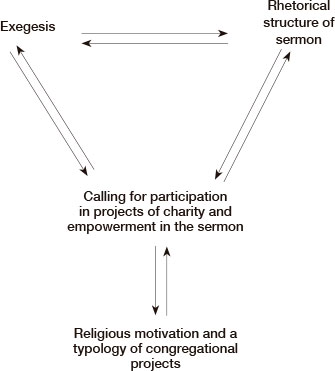

All three concepts described earlier are related to the central concept of calling on the listeners for participation in projects of charity and empowerment by the preachers in the sermons.

The following model illustrates the relations between the central concept and the three concepts identified earlier, as a grounded theory for the practice of preaching with Matthew 25:31-46 as sermon text in South Africa.

5. CONCLUSION

The theory for practice of preaching from Matthew 25:31-46 in the South African context consists of three concepts (see the model) which are in a close relationship to the central concept of calling for participation in projects of charity and empowerment in the sermon which integrates all the categories and concepts. This model also shows the steps in preparing and delivering the sermon on this sermon text, as well as the resultant actions of church members in projects directed to the poor.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Auer, A. 1977. Die Bedeutung des Christlichen bei der Normfindung. In: J. Sauer (ed.), Nonnen im Konflikt (Freiburg: Herder), pp. 29-54. [ Links ]

Berkhof, H. 1973. Christelijk geloof. Second printing. Nijkerk: Callenbach. Charmaz, K. [ Links ]

_______. 2006. Constructing grounded theory. A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Combrinck, H.J.B. 1987. Matteus 25:14-30. In: C.W. Burger, B.A. Müller & D.J. Smit (eds.), Riglyne vir prediking oor die gelykenisse en wonderverhale (Kaapstad: NGKerk-Uitgewers), pp.69-82. [ Links ]

_______. 1991. Dissipelskap as die doen van God se wil in die wêreld. In: J.H. Roberts, W.S. Vorster, J.N Vorster & J.G. van der Watt (red.), Teologie in konteks (Halfway House: Orion), pp.1-31. [ Links ]

Crossan, J.D. 1998. The birth of Christianity: Discovering what happened in the years immediately after the execution of Jesus. San Francisco: Harper. [ Links ]

Davis, W.D. & Allison, D.C. 1988-1997. A critical and exegetical commentary on the Gospel according to Saint Mathew. Three volumes. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

De Roest, H. P. & Noordegraaf, H. 2009. "We learned it at our mothers' knees". Perspectives of churchgoing volunteers on their voluntary service. Reformed World 59(3):213-226. [ Links ]

Friedrich, J. 1977. Gott im Bruder Eine methodenkritische Untersuchung von Redaktion, Überlieferung und Traditionen in Mt 25, 31-46. Stuttgart: Calwer Verlag. [ Links ]

Ganzevoort, R.R. 2009. Forks in the road when tracing the sacred. Practical Theology as hermeneutics of lived religion. Presidential address to the 9th Conference of the International Academy of Practical Theology, Chicago. [ Links ]

Glaser, B.G. 1978. Theoretical sensitivity. Advances in the methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press. [ Links ]

Grundmann, W. 1975. Das Evangelium nach Matthaüs (4th ed.). Berlin: Evangelische Verlag. [ Links ]

Hagner, D.A. 1995. Matthew 14-28. Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 33a. Dallas, Texas: Word Books. [ Links ]

Hill, D. 1972. The Gospel of Matthew. London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott. Holton, J.A. [ Links ]

_______. 2007. The coding process and its challenges. In: K. Charmaz & A. Bryant (eds.), The SAGE handbook of grounded theory (Los Angeles-London-New Delhi- Singapore: Sage Publications), pp. 265-289. [ Links ]

Hultgren, A.J. 2000. The parables of Jesus: A commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Immink, F.G. 2005. Faith. A practical theological reconstruction. Grand Rapids, MI. / Cambridge, UK: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Immink, G. 2010. Een methode van preekvoorbereiding. In: H. van der Meulen (ed.), Als een leerling leren preken. Preekvoorbereiding stapsgewijs (2nd printing) (Zoetermeer: Boekencentrum), pp. 9-20. [ Links ]

Jeremias, J. 1963. The parables of Jesus. Translated by S.H. Cooke (2nd ed.). New York: Charles Scribner & Sons. [ Links ]

Jeurissen, R. 1993. Peace and religion. An empirical-theological study of the motivational effects of religious peace attitudes on peace action. Kampen/Weinheim: Kok/ Deutscher Studien Verlag. [ Links ]

Jones, I.H. 1995. The Matthew parables. A literary and historical commentary. Leiden- Boston: Brill. [ Links ]

Jonker, W.D. 1989. Uit vrye guns alleen. Pretoria: N.G. Kerkboekhandel. [ Links ]

Lamprecht, J. 1992. Out of the treasure. The parables of the Gospel of Matthew. Louvain Theological and Pastoral Monographs 1. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Long, T.G. 2005. The witness of preaching. Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Luz, U. 2005. Matthew 21-28. A commentary. Translated by James E. Crouch. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Nielsen, J.T. 1971 (I) 1974 (II). Het evangelie naar Mattheüs. Nijkerk: Callenbach. [ Links ]

Nolland, J. 2005. The Gospel of Matthew. A commentary on the Greek text. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Osmer, R.R. 2008. Practical theology. An introduction. Grand Rapids, MI/Cambridge, U.K.: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Pieterse, H.J.C. 2009a. Beskouinge oor die prediking in situasies van armoede volgens homiletiese literatuur. Praktiese Teologie in Suid-Afrika/Practical Theology in South Africa 24(1):134-148. [ Links ]

_______. 2009b. Prediking oor die koninkryk van God: 'n Uitdaging in 'n nuwe konteks van armoede. HTS Teologiese Studies/HTS Theological Studies 65(1), Art. #106, 6 pages. DOI:10.4102/hts.v65il.106. [ Links ]

_______. 2011. An open coding analytical model of sermons on poverty with Matthew 25:31-46 as sermon text. Acta Theologica 31(1):95-112. [ Links ]

_______. 2012. A grounded theory approach to the analysis of sermons on poverty: Congregational projects as social capital. Verbum et Ecclesia 33(1), Art. #689, 7 pages. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ve.v33i1.689. [ Links ]

Pleizier, T. 2010. Religious involvement in hearing sermons. A Grounded Theory study in empirical theology and homiletics. Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

Putnam, R.D. 2001. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Reinstorf, D. & Van Aarde, A.G. 1998. Jesus' kingdom parables as metaphorical stories: A challenge to a conventional worldview. HTS Teologiese Studies/HTS Theological Studies 54(3&4):603-622. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, P. 1994. Oneself as another. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Schweizer, E. 1978. The good news according to Matthew. London: S.P.C.K. [ Links ]

Snodgrass, K.R. 2008. Stories of intent. A comprehensive guide to the parables of Jesus. Grand Rapids, MI/Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Swinton, J. & Mowat, H. 2006. Practical theology and qualitative research. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Van Aarde, A.G. 1994. The historical-critical classification of Jesus' parables and the metaphoric narration of the wedding feast in Matthew 22:1-14. In: A.G. van Aarde God-with- us: The dominant perspective in Matthew's story, and other essays (Pretoria: Gutenburg), pp. 229-247. [ Links ]

_______. 2007. 'Jesus' mission to all of Israel emplotted in Matthew's story. Neotestamentica 41(2):416-436. [ Links ]

_______. 2008. "Op aarde net soos in die hemel": Mattheus se eskatologie as die koninkryk van die hemel wat reeds begin kom het. HTS Teologiese Studies/HTS Theological Studies 64(1):529-565. [ Links ]

Van der Ven, J.A. 1993. Practical theology: An empirical approach. Kampen: Kok Pharos. [ Links ]

Van der Ven, J.A., Dreyer, J.S. & Pieterse, H.J.C. 2004. Is there a God of human rights? The complex relationship between human rights and religion: A South African case. Leiden-Boston: Brill. [ Links ]

Van Zyl, H.C. 1999. Matteus. In: W. Vosloo & F.J. van Rensburg (eds.), Die Bybelmillennium (Vereeniging: Christelike Uitgewersmaatskappy), pp. 1111-1187. [ Links ]

Via, D.O. 1987. Ethical responsibility and human wholeness in Matthew 25:31-46. Harvard Theological Review 80:97-100. [ Links ]

Wepener, C. & Cilliers, J. 2010. Ritual and the generation of social capital in contexts of poverty. In: I. Swart, H. Rocher, S. Green & J. Erasmus (eds.), Religion and social development in post-apartheid South Africa (Stellenbosch: SUN Press), pp. 417-430. [ Links ]

Weren, W.J.C. 1979. De broeders van den Mensenzoon: Mt.25, 31-46 als toegang tot de eschatologie van Mattheüs. Amsterdam: Ton Bolland. [ Links ]

1 The article is part of a project with financial support by the National Research Foundation.

2 For this interpretation, see also Nielsen (1974:77), Grundmann (1975:528) and Weren (1979:115).