Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.32 supl.16 Bloemfontein Jan. 2012

Siyazama entrepreneurial development project: challenges of a community-university partnership within a faculty of theology

Marietjie J. BothaI; Ruth M. AlbertynII

IProgramme manager: Capacity building, Unit for Religion and Development Research, University of Stellenbosch. E-mail: mjb@sun.ac.za

IIResearch Associate, Centre for Higher and Adult Education, Department of Curriculum Studies, University of Stellenbosch. E-mail: rma@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Calls for global relevance and accountability are prevalent in private-public partnerships. Current community engagement projects in higher educational institutions reflect this focus. The academic partner can play a boundary spanning (bridge building) role in a community-university partnership. The university partner often enters the partnership without full realisation of the challenges of its role. The Siyazama Craft Project, an entrepreneurial development intervention for poverty alleviation in Stellenbosch is an example of the boundary spanning role of the academic partner in the Faculty of Theology. This intervention is in line with the community interaction policy of the faculty and the university. The Siyazama entrepreneurship project is described, and challenges experienced during the course of planning, implementation and evaluation are presented. Identification of challenges in projects of this nature could provide insight for university partners in development projects. Findings could be applied to the broader context of public-private partnerships, which form part of corporate social responsibility projects in response to needs for relevance, accountability and responsible sustainable development.

Keywords: Entrepreneurial development projects, Power, Powerlessness, Empowerment, Partnerships, Community interaction.

Sleutelwoorde: Entrepreneuriese ontwikkelingsprojekte, Mag, Magteloosheid, Bemagtiging, Vennootskappe, Gemeenskapsinteraksie.

1. INTRODUCTION

The call for relevance and accountability of higher educational institutions (HEIs) is in line with the global call for ethical practice in public-private partnerships in various contexts (Strier 2011; Backstrand 2008; Bloland 2005). Corporate social responsibility initiatives are examples of responses to this call for greater relevance. HEIs response to this challenge is evident in the application of the scholarship of engagement in community engagement projects at all universities in South Africa (Le Grange 2005; Waghid 2002). Knowledge and knowledge production is thus seen as being situated within a broader context and the importance of application of knowledge requires greater involvement with local communities and governments (Gibbons et al. 1994; Boyer 1990, 1997). Thus what is needed is socially robust knowledge where there is a balance between relevance and science (James 2006).

Universities should therefore be centres of a nation's work and science should be of practical service in the context where the university is situated. According to the community interaction (engagement) policy of the Faculty of Theology, Stellenbosch University, community is seen

... as the single most important term in ecumenical circles to reflect on the nature and calling of the church and on the nature and destiny of humanity (Faculty of Theology 2008a:1; August et al. 2009).

Furthermore, the importance of a holistic contextual perspective of community is also acknowledged by viewing a community within its complex socio-historical context: "... ecological, ecumenical and contextual, diverse and inclusive, not homogenous and exclusivist" (Faculty of Theology 2008a:2). There should be an active respect for the challenges and concerns faced by society (Albertyn & Daniels 2009) through meaningful interaction between universities and the communities where they are located. Developing entrepreneurial skills in communities is one such an example of co-operation of academics in the environment where universities are situated.

Responsible development does not seek to satisfy the corporate social responsibility projects of the powerful partner in the dyad at the expense of the less powerful stakeholder. Power, in whatever form, may play a role in keeping one partner powerless and thus jeopardise the long-term sustainability of projects. Power may be retained in various ways such as expertise, resources, moral or welfare approach on the one hand or through the powerless, passive, fatalistic attitudes on the other hand. Any of these power manifestations may hinder the development efforts of the partnership. Sustainable development should therefore ensure that parallel benefits accrue to both parties.

According to Strier (2011), the building of significant partnerships between universities and communities will always be a complex task, which generates multiple tensions. The university partner often enters the partnership without full realisation of the challenges of its role. The policy for community interaction in the Faculty of Theology notes "[t]he need for redressing past injustices in the Faculty is of extreme importance and taken very seriously" (Faculty of Theology 2008a:5). It is not known to what extent these challenges have been systematically discussed and documented. In the light of the possible tensions associated with the community engagement challenge, it could be constructive to report on the challenges of such a partnership as encountered in the Siyazama entrepreneurial project conveyed in this article. Taking cognisance of the challenges may provide a roadmap for academics embarking on a development project of this nature. By reporting on the process and reflection on practice, challenges and pitfalls can be highlighted and lessons learned could be applied in other development contexts where university-community or broader public-private partnerships exist.

In this article the challenges related to the two domains of boundary spanning are addressed and will illustrate the important role of academics in the university-community partnership. The literature related to power and powerlessness and partnerships are relevant and are discussed. This is followed by a description of the Siyazama Craft Project, an entrepreneurial development project in the Faculty of Theology at Stellenbosch University. Finally, challenges in development projects are identified in the light of the two boundary spanning domains or roles, which were identified through literature and confirmed in the development project, described.

2. THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

In the discussion on relevance and sustainability of public-private partnerships, it is important to gain theoretical insights on the concepts of power and powerlessness. Power, powerlessness and empowerment are integrally part of the relationships in partnerships and are therefore discussed as a background to describing the example of a university-community partnership initiative in the Faculty of Theology, Stellenbosch University.

2.1 Power and powerlessness

The Faculty of Theology links with the Hope project of Stellenbosch University and the thematic focus is on the promotion of human dignity. The community interaction policy of the Faculty indicates that the nature of theology is in essence a pedagogy of hope. According to the overall strategic plan of the Faculty, the focus on promoting human dignity requires critical reflection and calls for accountability (Faculty of Theology 2008b: 1). This call for critical reflection leads to discourses of power. At the heart of development efforts are power relationships. Weerts and Sandmann (2010) assert that in the past many university-community projects failed because the initiatives were one sided with the community acting as passive recipients. Power can be wielded through the welfare approach, paternalistic or mission-oriented approaches characteristic of earlier theories of development, which could have been mirrored in the development approach applied in the church in the past. In these approaches the experts bring knowledge and resources and in the process benefit from the publicity of moral/ethical corporate strategies in various "deserving" contexts (Pereira s.a.).

The question needs to be asked: "How much power is actually being placed in the hands of the 'partners' (deserving recipients) in the development efforts?" The recipients may be considered partners due to the focus on participation in current day development theory; however, this participation may only be in word but not in deed. Pretty (1994) sets out a typology of seven incremental levels of participation in development efforts, from passive participation to self-mobilisation. Participation is key to sustainable development efforts (Pellisery & Bergh 2007; Swanepoel & De Beer 2006). Cognisance should be taken of the power dynamics in partnerships to ensure that the projects are mutually beneficial in the long-term.

Powerlessness in various individuals, groups and communities spawns the need for empowerment interventions, as powerless individuals lose their ability to make choices and are more subjected to external prescriptions of others (Albertyn et al. 2002). However, it should be noted that powerlessness is a relative concept, which is dependent of the type of capital valued in a particular situation. "Acting with" one another in developmental work is preferable to 'acting on' those who need or want to learn (Taylor 1993). "Acting on" would be characterised by a top-down approach to development. Procee (2006:241) states that reflection "takes a critical stance toward the (repressive) actual situation, thus opening up a horizon of liberation".

Feelings of hopelessness or helplessness need to be changed through lived experience that can open up new possibilities for naming and acting in the world. An intervention may indeed be necessary to break the spiral of powerlessness. Nevertheless, the end goal should always be to foster and facilitate empowerment. Empowerment refers to "the ability to make choices and, more than that, it refers to the ability to change" (Kabeer 2005:14). This process is not externally driven but internally motivated. The process of empowerment requires a long-term process and strategy with the "powerful" partner sequentially relinquishing power in the partnership. This process is complex and needs to be approached sensitively with a particular rationale and strategy in place. Empowerment is a process, which does not occur in a once off intervention (Kabeer 2005; Laverack 2005).

In facilitating empowerment, focus should be placed on the individual as being central to the process in an attempt to diminish the difference in power between the facilitator and the participants. By creating opportunities that allow them to experience success with small immediate tasks, their self-esteem will be bolstered. Powerless individuals or groups often have a strong natural support network and they should be encouraged to tap into this network. It is also important to ensure that they are offered the skills to help them make the choices that are important to their life circumstances (Albertyn et al. 2002). These empowerment principles should be applied in the community-university interaction. However, the value of the benefits to both partner needs to be borne in mind otherwise the powerful-powerless dyad will be perpetuated.

2.2 Partnerships

The term "partnership" seems to imply a two-way process and participation should be part of the process. Participation is in fact seen as an important element of empowerment (Swanepoel & De Beer 2006, 1998). Often the powerful partner who is seen as the provider of expertise and resources has a paternalistic attitude, which is counterproductive to the concept of partnership. The "powerless" partner does, in certain circumstances, have relative power depending on the values within their particular context. Openness to the relative definition of power will acknowledge respect for the community members in terms of what is valued in their context. Curry-Stevens (2007) refers to the post-structural recognition of the pluralised sites of domination and that there are consequently multiple systems of oppression in society. Oppression and liberation are therefore context-specific. Praxis (action informed and linked to particular values) proposes that dialogue or deliberation is not only about deepening understanding, but also to make a difference as a co-operative activity with respect as a value at its very base (Prych 2007).

Social engagements often engender contexts appropriate for valuable change and learning (Bartlett & Elliott 2008). Once there is the chance to engage with the "others" who think differently from our own way of thinking, there is the chance to actively change our practice. Such development is characterised by greater levels of abstraction and de-contextualisation rather than the mere specifics of human practice (Guile & Griffiths 2001). This process would lead to change or transformation (Engeström et al. 1995). Change is required from each of the partners in the process of development within the university-community partnership. Kreber (2005) states that the real question is whether the research conducted made a difference in the lives of those involved. Participatory and democratic structures of community-based research projects are fundamental to how the university fulfils its public mission through research (Berman, 2007). Calleson et al. (2005) summarise the measure for community-engaged scholarship and these relate to both academics and the community. For community-engagement to be considered scholarly, communication, assessing and addressing needs to solve identified problems are important in the community setting (Calleson et aI. 2005).

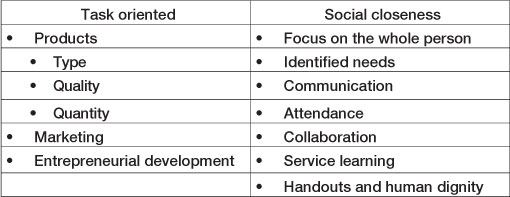

A mutually beneficial partnership between all stakeholders is thus crucial in the social development process. This partnership needs to be reflected on and monitored during the course of such an initiative. Weerts and Sandmann (2010:638) assert that what is needed are boundary spanners who build bridges between both constituencies. Boundary spanning in the context of university-community engagement is a complex set of activities at both the individual and organisational level. Two domains may differentiate boundary-spanning roles: task orientation and social closeness. The university partner has a potential role to play in ensuring the bridges are built and sustained in such a way that there are reciprocal sustainable benefits to both parties in the partnership. These two roles of task orientation and social closeness are discussed in relation to the community project in this article.

In the light of the above discussion of power and partnerships, the context of the Siyazama university-community partnership is presented.

3. ENTREPRENEURIAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT: SIYAZAMA CRAFT PROJECT

The project is described by focusing on the background and context of the project in Stellenbosch. The implementation process and the outcomes of the project are discussed. Finally the challenges of the process of implementing a university-community partnership are presented.

3.1 Background of the project

In the Unit for Religion and Development Research (URDR), Faculty of Theology, the mission and focus on human dignity is central as indicated in the overhead strategic planning of the Faculty. This focus on human dignity is in line with the millennium development goals (Faculty of Theology 2008b). In 2006 a group of unemployed women (adults) of Kayamandi, a "disadvantaged" community in Stellenbosch, approached the URDR and specifically expressed the need for craft training that might lead to income generation. These women are caregivers of primary school children who benefit from a feeding scheme at the local Primary schools (sponsored by Stellenbosch Community Development Programme, a nonprofit organisation), and in exchange for this, caregivers are responsible for a food garden at the school.

People in this community are classified as being very poor and have minimal recourses to improve their circumstances. This area has the highest unemployment (32.3%) in Stellenbosch and most people (56.5%) live in informal dwellings (URDR 2005). Many rural areas hold potential for the development of micro enterprises and thus self-employment. Unfortunately few of these communities are meeting this development challenge with local initiative. Women are the most vulnerable as many of them are illiterate and have no prospect of employment in the formal sector. However, previous research conducted by the URDR (2005) identified a high degree of bonding in this community. This indicates that there is a sense of community and the relative positive level of bonding amongst the community members creates an optimistic outlook for projects to be undertaken.

The Kayamandi Siyazama Craft Project is a non-formal adult education project that focuses on teaching of handicraft and entrepreneurial skills. Siyazama is a Xhosa word that means: "we are trying". The short-term objectives are to identify and facilitate skills training; train and develop entrepreneurial skills in order to establish micro enterprises; and develop products indigenous to the Kayamandi community and Stellenbosch for the tourist market. The long-term goals are poverty alleviation; promotion of human dignity; empowerment of participants; the development of human potential, community development, capacity building; and improvement in quality of life in the Kayamandi community.

Most participants in the Siyazama project live in informal housing with an average of six persons per household. The participants are all females and mainly Xhosa-speaking who were either unemployed or have informal part-time work. Their main source of income is child support grants. At present 30 ladies are trained. The average number is 18 participants per meeting. Participants join and leave the programme according to their needs and the fulfilment thereof. In all the classes there are small babies and toddlers that accompany mothers/caregivers. Training meetings for the participants are conducted once a week over a period of 43 weeks. This is presented in a meeting room of the Faculty of Theology and the project is managed and monitored by the one author of this article. Four facilitators from the Kayamandi community assisted with training and act as interpreters. An independent interpreter assists with individual interviews.

3.2 Project process and outcomes

The focus of this article is on the reflection on the implementation of entrepreneurial development as part of the university-community partnership. The findings of each of the stages of implementation are not reported in detail but are described as a point of departure for the reflection process that helped to produce a list of challenges which could be organised into the two domains of boundary spanning, namely task oriented and social closeness. The implementation strategy using participatory action research is briefly described and the outcomes are presented.

3.2.1 Implementation

The participatory action research approach (PAR) is applied during the course of the implementation of the project and monitoring and evaluation takes place during the process. The PAR approach uses guidelines based on scientific research that proved to be successful in adult education programmes that focus on the transfer of skills and the development of human potential (Botha et al. 2007). Participants are involved in all decisionmaking. The PAR approach follows a cycle of planning (problem analysis); actions (implementation of the strategic plan); observation of activities; evaluation of actions; and reflection (reflect on results of evaluation, on action, on the research process and on identifying a new problem).

Monitoring of the project and assessment of progress is continuous and done through direct observation, informal discussions, questionnaires, field notes and individual and group interviews. Effectiveness of the programme is evaluated through the review of outcomes based on scientific research.

This evaluation is helpful to revise the plan and action activities. Questions of Posavac and Carey (1997:51-60) are applicable. These questions include: Does the programme meet the needs of the people to be served? Do the people accept the programme? Does the programme match the values of stakeholders? Do the outcomes achieved match the goals? Are resources devoted to the programme being expended appropriately? Empowerment of participants is ascertained using qualitative data from in-depth and semi-structured interviews.

3.2.2 Outcomes

Based on observation and reflection by the university partner representation, the project is successful in reaching short-term goals. Evidence includes:

- Development of skills;

- Improvement in the quality of items produced, and developing and manufacturing products for the tourism industry;

- Feedback from participants, observations and results from interviews indicate that they want to learn more about the production of handicraft items and wish to produce items that they could sell to generate an income;

- Entrepreneurial principles of costing and pricing of all items are discussed in detail. All participants enrolled for a course in business skills presented by Matie Community Service (division Entrepreneurship and business skills) in 2010. Income is generated through selling of goods to tourist outlets and in some cases this is the only income of the household. Payment for items sold is a very big motivational force and encourages them to work accurately;

- Five participants started their own micro-enterprises.

This training and skills acquired made a positive contribution to their quality of life. Continuous feedback is given to participants and this reinforces a relationship of trust and openness among the group and facilitators.

In achieving the short-term goals, the long-term goals come into play.

- Poverty alleviation is addressed and participants generate an income.

- The development of human potential and promotion of human dignity is observable in their self-management where training meetings continue when the project manager is not available. They organise themselves and those who are more competent and experienced take responsibility for certain tasks and assist newcomers. They take charge of their own life this way. This increases self-confidence and human dignity is enhanced. They feel very much in control in a situation like this and this fosters empowerment.

- Qualitative data on the empowerment status of participants indicates that participants feel more in control of their lives and this is related to their belief in competence and self-worth.

- Community development, capacity building and improvement in quality of life in the Kayamandi community are continually addressed.

It thus appears that the two domains of boundary spanning as identified by Weerts and Sandmann (2010), task orientation and social closeness, are met in the implementation and observation of the outcomes of the Siyazama project.

3.3 Challenges

In reflecting on the process of implementation and evaluation as part of the PAR process, it was noted that there are various challenges associated with a project of this nature. Taking note of the challenges may provide insights to other universities who are engaging in partnerships for entrepreneurial development.

3.3.1 Focus on the whole person

The focus on the promotion of human dignity is noted in the focus of Faculty of Theology's overhead strategic plan: "One can argue that all Christian theology is in essence focussed on the promotion of human dignity - or should be" (Faculty of Theology 2008b:2). Swanepoel and De Beer (2006) and Pereira (s.a.) state that the real goal of development is to eradicate poverty and release people from the deprivation trap so that they are free and self-reliant and gradually improve the situation themselves. The greatest challenge is to ensure that this project is not merely a welfare programme that only addresses symptoms of the situation and do nothing about the status quo. The negative spin-off of the project might be that the participants became increasingly more dependent on the project because their need for relief does not end.

It is a challenge to focus on the whole person in her environment and on the total transformation so that her situation can be changed. Participants are part of decision-making, mobilised to participate in all aspects from planning to evaluation and take ownership and manage the project. The abstract needs of self-reliance and human dignity is addressed so that the project is more than merely a relief operation. The results of the empowerment research indicated an increase in self-esteem, confidence and control in interpersonal relationships with significant others. Human dignity is promoted by giving participants recognition for their efforts and lessening feelings of powerlessness. The financial gain improves self-reliance and independence and creates a better home environment for child development and improves the quality of life. Development of leadership qualities, communication skills and personal growth was observed.

3.3.2 Identified needs

It is challenging to let people believe that they can do something about their identified needs (through PAR) and, at the same time, to ensure that the articles produced should be marketable and in demand. It is not always possible to make items that are in demand. It is important not to raise false expectations concerning financial reward and to be open about the aims and limitations of a specific venture. Actions during the training meetings are limited to satisfying a single need. Participants do have different needs and also different perceptions about the same need. Needs are prioritised according to urgency (orders) and do-ability (for example the need to make tracksuits for schools).

3.3.3 Communication

Language is a barrier. Although the facilitators are Xhosa- and English-speaking and translate what the manager says, it is impossible to determine if they translate correctly. It is impossible to detect nuances in the feedback of participants. Participants do not always understand terminology/jargon used. When they have poor knowledge of the subject discussed chances are that they will not understand at all. Although an interpreter helps with interviews, conversations and feedback are taped and transcribed to ensure accuracy. If there are tensions between certain personalities in the class, it is very difficult for the facilitator to follow conversations and translations of facilitators. English-speaking participants need to be relied on.

3.3.4 Products

In an entrepreneurial development project of this nature, products manufactured need to be fashionable, of good quality, and compete with others products on the market. Various aspects are important. These aspects relate to the type, quality and quantity of the product.

It is extremely difficult to identify the type of products that are sellable, fashionable, and competitive in price with other products on the market, especially those manufactured by "empowerment projects". Market investigation by the project manager revealed that people are often exploited in job creation projects. They are paid very little for work that takes ages to make and these products are offered in the market at a very low price. A highlight in training activities is outings to do market research, visit outlets, markets and other community development endeavours. Most participants have never before had the opportunity to browse in shops in Stellenbosch and Franschhoek and for a few, eating in a restaurant and with knife and fork was a first experience. Participants do not have the knowledge and self-confidence to independently develop products or to design new products. They need guidance when it comes to decisions regarding style, types of fabric to use, colour combinations and decoration. They are not shy to voice their opinion. They are very creative and adapt and change designs to suit their own style. However, their exposure to outlets, the fashion world and trends are limited. Unfortunately one cannot manufacture items that are not compatible with others in the retail market.

Quality control is vital and participants are paid after a strict quality control and only when items are correct. Quality means different things to different people and for some participants this is not so important especially if an item is for own use. There is great variation in the competencies of participants. Participants are encouraged to work accurately and they often need to unpick stitching and re-do certain activities. This way those who had the idea that they could keep poor quality items for themselves are discouraged to do so. Some participants have very poor eye-hand coordination, are unable to hold scissors properly and cut patterns or fabric accurately. However, they expressed the need to receive training to learn these skills, but this influences the quality of the finished article. If there is an order for items of a specific size, it is important for the manager to do all the cutting to ensure that it is perfect. Poor eye sight also influences quality. Some make use of reading glasses (different strengths are available in class) but a few had severe eye problems. They had eye tests and got prescription glasses that now have become a status symbol and envy of many.

Quantity is also an important aspect to consider in terms of the products made in the project. When a product is identified, samples are made (participants are paid for this) and the project manager approaches retail outlets. Stock is produced based on the demand and as soon as new orders are received. Problems arise when skilful participants are absent and orders take longer than anticipated to deliver. In order to deliver on time, the number of meetings per week had to be increased. The group (at present) does not have the capacity to deliver products within a short time on a grand scale (such as 500 conference bags). All the necessary equipment is not available (for example industrial machines). Therefore the group work with external partners on occasion when the need arises.

3.3.5 Marketing

Many participants lack the confidence to market their products even in their own community. It is necessary to address the implementation of more aggressive marketing techniques. They expressed the need to establish an outlet at a retail development in their community and they are in consultation with other entrepreneurs in the area but these discussions are very laid back and take a long time.

3.3.6 Handouts and human dignity

It is important to facilitate the understanding that the project is not a hand out. All materials required in skills training is provided free of charge for the production of several items. They are allowed to keep the first articles produced to practice their skills, but they have to pay for the material bought for extra articles they produce to sell themselves. The taxi fare of participants are paid. Some participants prefer to walk and keep the money. Only participants that demonstrate their commitment by regular attendance over a period of time receive a sewing kit worth R250. This includes basic sewing equipment to produce items at home.

There are so many vulnerable communities who out of desperation will accept any payment that might promise a better life. The skills and the economic needs of participants in the project do not always match. It should not be overlooked that this modest income generated, supplements their income and social grants. Success cannot be measured in terms of income only. It is about the whole person and the positive effect this exposure to training has on their human dignity. It provides a way for them to believe in their abilities and potential and for them to affect their circumstances for the better.

3.3.7 Entrepreneurial development

Participants in the more experienced group sell articles regularly that provide a small income. For the majority this is the only income in the household. Their target market is people in their own community. Five participants started their own micro-enterprises. Feedback indicated that many participants still experience problems with marketing, pricing and costing, despite the fact that basic business principles are continually addressed during training, and a formal business skills course provides hands on experience. They were offered financial support in exchange for information on orders they receive and their pricing and costing detail of these items. Two verbal requests were received but no cost analysis. Not all participants are entrepreneurs. Although most were keen to sell items, not all expressed the need to start their own micro-enterprises. The needs, values and level of skills of participants differ. Some participants were engaged in this activity in a response to pressures they felt from their current life situation. They are only interested to satisfy their personal needs.

3.3.8 Attendance

Irregular attendance because of personal problems and the weather conditions hinders the teaching of skills. This irregularity and constant arrival of new participants is an obvious irritation to the regulars and they organised themselves into two smaller groups - an advanced group and newcomers. A reward system was implemented for those who do attend regularly, namely a gift packet with left over fabrics to produce items at home and sell them. The payment participants receive for items made for shops are a great joy and a motivational force for participants. This also encourages them to work accurately. As soon as payments are made, the number attending increases at the next meeting and new people join the project. Participants love to enrol for short courses and workshops but it is embarrassing for presenters when attendance is irregular. They very often have other commitments just after lunch.

3.3.9 Collaboration within the group

It has not been possible to establish a factory line-production style and ascribe certain activities to certain individuals. Skilled participants sometimes work together but they are obviously irritated when less experienced group members do not work neatly and the quality of a finished product is influenced. The majority prefer to work in a group situation but to produce their own article. Observation revealed that group contact seems to encourage participants and contribute to confidence. They do organise themselves and those who are more competent in a specific activity take over this responsibility. It was very positive that they took charge of their own life in this way.

3.3.10 Service learning

Service learning is one approach to community engagement. Service learning is defined as "... a transformative, learner-centred and community-oriented pedagogy in all academic programs of the Stellenbosch University" (Stellenbosch University [SU] 2012). It is therefore a great challenge and also an opportunity to align the curriculum of the Department of Practical Theology and Missiology to the needs of a community so close to the University. This project creates the opportunity to meaningfully integrate teaching, research and community service, which is in line with the community interaction policy of the University and the Faculty of Theology (2008a). The mission statement of the University emphasises that a concern with knowledge is a university's essential and distinctive raison d'etre, and that this concern with knowledge is understood to include a responsibility to serve the well-being of the community (SU 2000:8). Dall'Alba and Barnacle (2007) believe that students need to learn how to "be" in the realities of the knowledge economy. There should be a shift from the emphasis on knowledge and skills acquisition to the preparation of students to deal with super complexity, which is a characteristic of modern society (Barnett 2004).

A module in-service learning was designed and final year students in Community Study, Management and Entrepreneurship (a four-credit module) are involved with the project. For many students this is their first introduction to a community in need. Students act as co-facilitators and fieldworkers and interviewed participants on aspects relating to their personal experiences and circumstances. An asset-based approach was followed to do a community analysis and need assessments, and identify competencies and assets of participants. This included open-ended and semi-structured interviews to document the "stories" of individuals. It is interesting to note that although participants generated an income through their involvement in the training programme, none of them disclosed this information in the interview with the students. This service learning opportunity helped to bridge the gap between academic training and practical skills required for future Christian leaders in the workplace. Feedback from participants indicated that they experienced this interaction positively and students treated them with compassion and respect. Students reported that this interaction gave them a better understanding of how to engage meaningfully with community members that experience social problems and suffering.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this article the ten challenges of the entrepreneurial development project, Siyazama, was discussed. The identified challenges could provide insight into the issues that are important in implementing a university-community partnership project. The boundary spanning role of the academic could be enhanced if the task oriented and social closeness domains of Weerts and Sandmann (2010:639) are addressed. The domains relevant to the case of the Siyazama development project relate to presented challenges of the boundary spanning role and are summarised below.

The challenges noted in the intervention for entrepreneurial development are both task oriented and related to social closeness. These two domains illustrate that it is not only what is done in social and entrepreneurial development, but also how it is done for development to be sustainable. The academic partner should be aware of these two domains and acquire the knowledge and skills to address both these domains in development initiatives. In any social development project, it is not sufficient to invest money in the project without a holistic planned strategy for implementation and evaluation (Botha et al. 2007; Pereira s.a.). This process of development requires systematic planning. The academic partner is ideally placed to play the role of boundary spanner.

In this article, reflection on the implementation of entrepreneurial development as part of the university-community partnership has been put forward. The focus was on reflection, which helped to produce a list of challenges, which could be organised into the two domains of boundary spanning. Further research could focus on various stages of the implementation process in development projects, as well as the results of participatory action research processes in entrepreneurial development projects of this nature.

Community engagement should not just be "window dressing". The university partner should not enter community engagement without a full realisation of the role challenges of the partnership. These challenges relate to the context and the changing notions of knowledge production. Within the global economy, knowledge production is no longer primarily located in the domain of higher educational institutions. Knowledge is created and used in many different sites including the community engagement setting. According to Bloland (2005), higher education is losing its knowledge monopoly. Therefore the importance of the mutual benefits in public-private (or community-university) partnerships needs to be underscored. Universities have much to gain from the interaction as is noted in the service learning benefits to student learning reported. Power thus is balanced, and there is a move away from the welfare approach to development with community as passive recipients, to a situation where reciprocal benefits manifest in both partners. It is imperative that a way towards balancing the community-university partnership is envisioned that will ensure that both parties benefit reciprocally. In this way power balances will be maintained and in so doing, a contribution will be made towards sustainable, responsible community engagement.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albertyn, R.M. & Daniels, P.S. 2009. Research within the context of community development. In E.M. Bitzer (ed.), Higher education in South Africa. A scholarly look behind the scenes. (Stellenbosch: Sun Media), pp.409-428. [ Links ]

Albertyn, R.M.; Kapp, CA. & Groenewald, C. 2002. Patterns of empowerment in individuals through the course of a life-skills programme in South Africa. Studies in the Education of Adults 33(2):180-200. [ Links ]

August, K.T.; Cloete, A. & Thesnaar, C. 2009. Faculty of Theology: Community Interaction. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Backstrand, K. 2008. Accountability of networked climate governance: The rise of transnational climate partnerships. Global Environmental Politics 8(3):74-102. [ Links ]

Barnett, R. 2004. Learning for an unknown future. Higher Education Research and Development 23(3):247-261. [ Links ]

Bartlett, B.J. & Elliot, S.N. 2008. The contributions of educational psychology to school psychology. In: T.B. Gutkin & C.R. Reynolds (eds.), The handbook of school psychology (San Francisco CA: Lawrence Erlbaum), pp. 65-83. [ Links ]

Berman, K. 2007. Shifting the paradigm: The need for assessment criteria for community engaged research in the visual arts. Unpublished paper delivered at the First International Conference on Postgraduate Supervision [Congress theme "Postgraduate supervision: The state of the art and the artists"] 23-26 April 2007. Stellenbosch University. Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Bloland, H.G. 2005. Whatever happened to postmodernism in higher education? No requiem in the new millennium. Journal of Higher Education 76(2):121-150. [ Links ]

Botha, M.J.; Van Der Merwe, M.E.; Bester, A. & Albertyn, R.M. 2007. Entrepreneurial skill development: Participatory action research in a rural community. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences 35:9-16. [ Links ]

Boyer, E.L. 1990. Scholarship reconsidered. Priorities of the professoriate. Princeton NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. [ Links ]

Boyer, E.L. 1997. Ernest L Boyer: Selected speeches 1979-1995. Princeton NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. [ Links ]

Calleson, D.C.; Jordan, C. & Seifer, S. 2005. Community engaged scholarship: Is faculty work in communities a true academic enterprise? Academic Medicine 80(4):317-321. [ Links ]

Curry-Stevens, A. 2007. New forms of transformative education: Pedagogy for the priviledged. Journal of Transformative Education 5(1):33-58. [ Links ]

Dall'alba, G. & Barnacle, R. 2007. An ontological turn for higher education. Studies in Higher Education 32(6):679-691. [ Links ]

Engeström, Y.; Engeström, R. & Kàrkkànainen, M. 1995. Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: Learning and problem solving in complex work activities. Learning and Instruction 5(1):10-17. [ Links ]

Faculty of Theology. 2008a. Community Interaction Policy: Concept Faculty of Theology. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Faculty of Theology. 2008b. Overhead Strategic Plan, Stellenbosch Faculty of Theology: Thematic initiative, first priority. Focus on the promotion/advancement of human dignity. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Gibbons, M.; Limoges, C.; Nowotny, H.; Schwartzman, S.; Scott, P. & Trow, M. 1994. The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Guile, D. & Griffiths, T. 2001. Learning through work experience. Journal of Education and Work 14(1):114-131. [ Links ]

James, M. 2006. Balancing rigour and responsiveness in a shifting context: Meeting the challenges of educational research. Research Papers in Education 21(4):365-380. [ Links ]

Kabeer, N. 2005. Gender equality and women's empowerment: A critical analysis of the Third Millennium Development Goal. Gender and Development 13(1):13-24. [ Links ]

Kreber, C. 2005. Charting a critical course on the scholarship of university teaching movement. Studies in Higher Education 30(4):389-405. [ Links ]

Laverack, G. 2005. Using a 'domains' approach to build community empowerment. Community Development Journal 41(1):4-12. [ Links ]

Le Grange, L. 2005. The 'idea of engagement' and 'the African University in the 21st Century': Some reflections. South African Journal of Higher Education 19 (special issue):1208-1219. [ Links ]

Pellissery, S. & Bergh, S.I. 2007. Adapting the capability approach to explain the effects of participatory development programs: Case studies from India and Morocco. Journal of Human Development 8(2):283-302 [ Links ]

Pereira, P. [s.a.]. Teaching lifeskills may be more empowering than other social investments. NGO Pulse [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.ngopulse.org [17 February 2011] [ Links ].

Posavac, E.J. & Carey, R.G. 1997. Programme evaluation: Methods and case studies. Fifth edition. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Pretty, J.N. 1994. Alternative systems of enquiry for sustainable agriculture. IDS Bulletin 2(25):37-48. [ Links ]

Procee, H. 2006. Reflection in education: A Kantian epistemology. Educational Theory 56(3):237-253. [ Links ]

Prych, T. 2007. Participatory action research and the culture of fear. Action Research 5:199-216. [ Links ]

Stellenbosch Municipality Integrated Development Plan. 2005. Third Annual Review. Stellenbosch: Local Government Municipal Council. [ Links ]

Stellenbosch University (SU). 2000. A strategic framework for the turn of the century and beyond. [Online] Retrieved from: http://www.sun.ac.za/university/StratPlan/index.htm [22 March 2012] [ Links ].

Stellenbosch University (SU). 2012. Community Interaction. [Online] Retrieved from: http://admin.sun.ac.za/gi/service%20learning/centre.htm [22 March2012] [ Links ].

Strier, R. 2011. The construction of university-community partnerships: Entangled perspectives. Higher Education 62(1):81-97. [ Links ]

Swanepoel, H. & De Beer, F. 1998. Community capacity building: A guide for fieldworkers and community leaders. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Swanepoel, H. & De Beer, F. 2006. Community development: Breaking the cycle of poverty. Cape Town: Juta. [ Links ]

Taylor, P. 1993. The texts of Paulo Freire. Buckingham UK: Open University Press. [ Links ]

URDR (unit for Religion and Development Research). 2005. Transformation Research Project-Stellenbosch. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://academic.sun.ac.za/theology/Centres/Egon/trp/stb/StbReport.pdf [5 July 2010] [ Links ].

Waghid, Y. 2002. Knowledge production and higher education transformation in South Africa: Towards reflexivity in university teaching, research and community service. Higher Education 43:457-488. [ Links ]

Weerts, D.J. & Sandmann, L.R. 2010. Community engagement and boundary-spanning roles at research universities. Journal of Higher Education 81(6):632-657. [ Links ]