Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.32 n.1 Bloemfontein Jan. 2012

The function of "weeping and gnashing of teeth" in Matthew's gospel

Zoltan L. Erdey; Kevin G. Smith

South African Theological Seminary. E-mail: Zoltan@sats.edu.za

ABSTRACT

On six occurrences (8:12; 13:42; 13:50; 22:13; 24:51; 25:30), Matthew recorded Jesus pronouncing judgment, using the idiom "weeping and gnashing of teeth". Each occurrence played a central role in the development of Matthew's theology, by communicating not only a fundamental component of the theme of judgment, but also an increasing force and potency of the event itself. It was discovered that the phrase may have four possible functions, namely (a) a system by which Matthew hoped to make the message of the particular passage unforgettable; (b) a prophetic anticipation of an aspect of the larger shape of history; (c) a linguistic device to increase the degree of emphasis or heighten the force given to the message of eschatological judgment; and (d) a literary connector holding together a number of specific passages of Scripture. In Matthew's case, the phrase glues together the passages that communicate a holistic theology of end-of-time judgment.

Keywords: Judgment Eschatology Gnashing of teeth Weeping

Trefwoorde: Oordeel Eskatologie Kners van tande Huil

1. INTRODUCTION

Largely, Matthean scholars recognize the emphasis that Matthew placed on the themes of eschatology and judgment (Streeter 1942; Bornkamm 1963; Marguerat 1981 [in Sim 2005:6-9]; Cope 1989; Stanton 1993; Hagner 1993a; Guthrie 1996; Balabanski 1997; Mitchell 1998; Keener 1999; Nolland 2005; Sim 2005). Within this dual theme, one is struck by the author's recurrent use of the idiom,![]() ("weeping and gnashing of teeth") (8:12; 13:42; 13:50; 22:13; 24:51; 25:30). Generally, interpreters acknowledge the unique nature of the phrase in the gospels (Rengstorf 1976; Davies & Allison 1991; Blomberg 1992; Hagner 1993; Senior 1998), but none deals with its particular function in Matthew's Gospel or his theology.

("weeping and gnashing of teeth") (8:12; 13:42; 13:50; 22:13; 24:51; 25:30). Generally, interpreters acknowledge the unique nature of the phrase in the gospels (Rengstorf 1976; Davies & Allison 1991; Blomberg 1992; Hagner 1993; Senior 1998), but none deals with its particular function in Matthew's Gospel or his theology.

Matthew was not a haphazard, hit-and-miss writer, but one with a distinctive purpose, rationale and theology. The essential belief of contemporary redactional investigation is that Matthew's Gospel is carefully designed, with smaller literary units cautiously and purposefully arranged to communicate a specific message. Therefore, it stands to reason that Matthew carefully constructed his writing on both macro and micro levels. This consideration then makes it likely that the writer was attempting not only to communicate something through his repeated use of the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth, but also to have a precise purpose(s) as well as a specific function(s).

Therefore, based on the frequency and distribution of this phrase, we contend that Matthew had a specific rationale behind the placement of the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth in his gospel. Therefore, we hope to answer two key questions, namely (a) what is the particular function of the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth in Matthew's Gospel and theology is and (b) what the nature of the contribution the expression makes to the theology of judgment in the gospel is.

2. THE THEME OF JUDGMENT IN MATTHEW

The purpose of this section is twofold, namely to demonstrate that judgment permeates Matthew's Gospel and to show that the theme of judgment is closely linked to the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth.

2.1 The work of David C. Sim

It is beyond the scope of this article to explore or repeat the work already completed by David Sim (2005) on issues connected with either (a) Matthew's rationale including judgment passages into his gospel, or (b) the function of such judgment pericopes. However, a brief synopsis provides the necessary background.

In terms of the first question, Sim commences with a chapter that is descriptive in nature, attempting to recognize and classify the exact nature and extent of the apocalyptic in apocalyptic literature in general. He identifies that the end-of-time speculations on judgment and apocalyptic eschatological function in the context of two primary elements, namely dualism and determinism (pp. 35-42). Consequently, Sim turns his attention to the eschatological event proper, where he identifies six design characteristics (functioning in the abovementioned contexts), namely (a) eschatological woes; (b) arrival of a saviour figure; (c) judgment; (d) fate of the righteous; (e) fate of the wicked; and (f) imminent expectations of the end of time (pp. 42-52). Because he is convinced that Matthew's eschatology and end-of-time perspective "must be examined in the same way as that other apocalyptic-eschatological writings are investigated" (p. 13), he adopts the above-mentioned characteristics as universally true for both inspired and uninspired literary works and thus applies these to Matthew's Gospel.

In terms of the second question, Sim highlights the five roles that apocalyptic eschatology serves in Matthew (pp. 223-241), namely (a) identification and legitimation; (b) explanation of current circumstances; (c) encouragement and hope for the future; (d) vengeance and consolation; and (e) group solidarity and social control.

Therefore, it seems that Sim presents an acceptable answer to the why and the how question on a macro level, namely why Matthew inserted apocalyptic judgment into every part of the gospel and how it functions in his gospel as a whole. This article is concerned with answering the more focused question, namely how Matthew uses the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth to bring across his theological point.

2.2 The prominence of the judgment imperative

Although other biblical writers share Matthew's interest in eschatology, this theme holds more prominence in Matthew's Gospel than in most New Testament books (with the exception of the Book of Revelation). The prominence of Matthew's judgment imperative seems discernible on four plains.

Firstly, Matthew 24, when compared to Mark 13, reveals the importance of the theme of eschatology and judgment. Presupposing Markan priority, Hagner (1993b) points out that Matthew's chief eschatological chapter (24) is significantly longer than that of his (redacted) source, Mark 13.1 "Clearly", explains Mitchell (1998:204),

Matthew thought that Mark’s apocalyptic discourse, though worthy of duplication, left out matters of grave importance ... [Matthew] almost triples it in length.2

From a redactional perspective, Matthew expands Mark's 13th chapter (24), and adds a new chapter (25), both of which expound on the realities of the final judgment. This reveals an interest in the general theme of eschatology and a concern with the finer details of the end of history.

Secondly, Matthew includes several eschatologically significant pericopes that are not found in Mark. Examples include the parables of the weeds (13:24-30, 36-43), workers in the vineyard (20:1-16), wedding banquet (22:1-14), ten virgins (25:1-13) and the last judgment (25:31-46) and their explanations. This supports the view that apocalyptic eschatology is an important theme to Matthew.3

Thirdly, the title Son of Man in Matthew's Gospel contains eschatological implications, and hints at the extent to which judgment permeates his gospel. Although disputed by a small minority of scholars (e.g., Vermes 1973; Chilton 1994), it seems most likely that the title Son of Man in Matthew is rooted in Daniel's exalted figure (Longenecker 1970). This is significant because it indicates Matthew employed this title in an eschatological context. Keener (1999:67) elaborates:

When the Pharisees think that Jesus "blasphemes" because he forgives sin, Jesus demonstrates the "Son of Man's authority on earth" (Matt. 9:6; Mark 2:10); he likewise claims authority for the Son of Man as "Lord of the Sabbath" (Matt. 12:8; Mark 2:28).

He then continues to observe that Christ's allusion to Daniel 7 becomes most unequivocal in Matthew 24:30 (to his disciples) and in Matthew 26:64 (to his opponents, ending the messianic secret). In other words, Matthew, through this title, presented Jesus as a larger-than-life person, more divine than human (although human nevertheless), who has the authority to judge humanity (Matt. 10:23).

Sim (2005:116) adds more weight to this point, correctly recognising that "only in his [Matthew's] gospel is there special emphasis that Jesus will preside as Son of Man".

The cluster of ideas . in 19:28 and 25:31, Jesus as Son of Man presiding over the judgment on his throne of glory, is attested nowhere else in early Christianity (Sim 2005:119).

Fourthly, Sim (2005:114-115) sets out a fuller picture of the theme of judgment in Matthew by providing a brief synopsis of Matthew's apocalyptic expressions and language. In terms of terminology, Matthew records Christ utilizing four primary expressions in referring to judgment, namely (a) ![]() ("the day of judgment"), used in 10:15, 11:22, 24 and 12:36; (b)

("the day of judgment"), used in 10:15, 11:22, 24 and 12:36; (b) ![]() ("end of the age"), used in 13:39, 40, 49; 24:3 and 28:28; (c)

("end of the age"), used in 13:39, 40, 49; 24:3 and 28:28; (c) ![]() ("on that day") in 7:22 (a variation in 24:36); and (d)

("on that day") in 7:22 (a variation in 24:36); and (d) ![]() ("the end") in 10:22 and 24:6.

("the end") in 10:22 and 24:6.

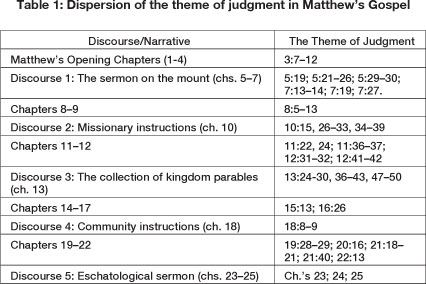

Therefore, it is notable that judgment passages permeate the entire Gospel of Matthew. However, to what extent does the theme of judgment permeate the Gospel of Matthew? To answer this question, it is valuable to observe the numerous judgment passages, in relation to the five-discourse hypothesis.4 While Matthew's Gospel is somewhat structurally mixed (Davies & Allison 2004; Gundry 1982), the five teaching discourses seem to be of primary importance to Matthew, as he characteristically alternates large blocks of discourse and narrative material. This is potentially significant, for a link appears to exist between the predominance of the five-discourse motif and the theme of judgment. A case in point is that each discourse ends on an unambiguously apocalyptic note (Hagner 1985, 63-64). A descriptive survey of judgment passages in the structural context of the five-teaching discourse reveals that Matthew's Gospel is laden with apocalyptic eschatology and judgment narratives.

It is apparent that judgment of the wicked, the unfaithful and the unprepared infuses not only the five discourses, but also the gospel in its entirety. Moreover, the phrase ![]() seems strategically placed in structurally and thematically significant or salient gospel sections, namely chapters 24-25 (Jesus' eschatological discourse and final hours before his arrest and passion), and chapter 13 (the hinge chapter of the Matthew's Gospel).

seems strategically placed in structurally and thematically significant or salient gospel sections, namely chapters 24-25 (Jesus' eschatological discourse and final hours before his arrest and passion), and chapter 13 (the hinge chapter of the Matthew's Gospel).

A number of scholars have identified chapter 13 as a major turning point of the Gospel. In fact, says Green, "it is the hinge on which the Gospel turns" (2000:31). This focal point is dichotomous; prior to this "break", the focus is on the crowds (public), whereas, after chapter 13, the focus shifts to the twelve disciples (private). Blomberg (1992) sees it as a progressive polarization, later repeated in the context of Jews (outsiders, as rejecters of Christ's ministry) and gentiles (insiders, as the new covenant people). However, a second facet of the centrality of chapter 13 is noticeable due to the complex and convoluted parallel between discourses one and five (5-7 / 23-25) and two and four (10 / 18). Hence, the kingdom parables remain the possible focal point of Matthew's gospel.

In the light of the above, it appears that Matthew systematically and uniformly positioned judgment passages, insuring their presence throughout the entire gospel.

3. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN JUDGMENT AND "WEEPING AND GNASHING OF TEETH"

Preliminary observations seem to indicate that a more than mere surface relationship exists between the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth, and the theme of judgment in Matthew's Gospel. This section seeks to identify the nature and function of this connection, through a brief analysis of the six passages that contain the idiom.

The faith of the centurion (8:5-14). In this passage, the evangelist first established that the only way to avoid weeping and gnashing of teeth is by accepting Christ's authority as the provider of salvation. False hope in one's ethnicity leads to a horrific fate (8:1-14).

In the story, Matthew shows Jesus articulating his amazement at the centurion's belief, and immediately follows with one of the most severe judgment warnings against unbelieving Israel. As Turner (2008:233) observes, "this frightening imagery marks one of the most sobering moments of Matthew's story of Jesus." Matthew makes his theological point and brings this pericope to a climax, recording Christ explaining that the subjects of his rejection will weep and gnash their teeth. However, this is no ordinary weeping and no ordinary gnashing of teeth. The terrible fate of those who find themselves outside will eternally experience the weeping and the gnashing of teeth .![]() The definite article(s) disclose the exclusive nature and horrific character of the effects of expulsion into the outer darkness (Turner 1963:173). There simply is no weeping like this weeping and no gnashing like this gnashing. Thus, the platform for the theme of judgment is set at an elevated intensity.

The definite article(s) disclose the exclusive nature and horrific character of the effects of expulsion into the outer darkness (Turner 1963:173). There simply is no weeping like this weeping and no gnashing like this gnashing. Thus, the platform for the theme of judgment is set at an elevated intensity.

The parable of the weeds (13:24-30, 36-43) and the parable of the net (13:47-50). The second passage illustrates that the coexistence of both true and false disciples does not indicate evaded judgment. On the contrary, a terrible destiny awaits the wicked (13:24-30, 36-43). Matthew then immediately underpins the severity and harshness of the final judgment by restating (in vivid eschatological language) the truth that such false disciples will weep and gnash their teeth in the furnace of fire (13:24-30, 36-43). The theme of judgment receives centre-point attention in the teaching heart of the gospel (i.e. the kingdom parables). No other parable achieves the goal of making the certainty and possibly even severity of judgment as tangible and real as this one. Matthew records Christ prefacing the weeping and gnashing of teeth idiom with the furnace of fire, signifying that the unrighteous shall weep and gnash their teeth in reaction to the pain and suffering inflicted by the fire. At this stage of the gospel, linking ![]() with physical pain is certainly unique, not only to the theme of judgment, but also to the gospels en bloc.

with physical pain is certainly unique, not only to the theme of judgment, but also to the gospels en bloc.

The repetition of the imagery of verse 42 in verse 50 then functions as an extremely serious, heightened warning, or, to use Lenski's (2008) terminology, "a mighty warning". One would think of parents who utter a warning to their children. The second time that the warning is uttered, the tone is far more serious, marking the end of talk and the beginning of action. Once again, the repetition of this vivid judgment metaphor validates the hypothesis that the theme of judgment in Matthew's Gospel moves from intensity to intensity, with the aid of each citation of the phrase. It seems Matthew is in the epicentre of his theological emphasis, as he continues to strengthen the theme of judgment in his gospel.

The parable of the wedding banquet (22:1-14). In the third pericope, the evangelist records Jesus' disclosing of the intense hostility and antagonism that false disciples exhibit towards the king (22:1-14), as they wilfully reject his open invitation to eternal bliss. Such a rejection earns them an eternity of weeping and gnashing of teeth. The truth communicated is again intense. Lacking the usual build-up, the theme of apocalyptic judgment appears suddenly in the second part of the story (vv. 11-14), with new intensity and force. In previous passages (8:12; 13:42, 50), the axiom fits the linguistic flow of the pericope. Here, in verse 13, this is no longer the case, as "the figurative language of the parable is frankly abandoned because it is unable to picture the reality" (Lenski 2008:858). The strength of this eschatological pronouncement reaches a new level of intensity and force.

A further relationship becomes apparent, namely the link through the emphatic phrase ![]() ("cast...into the outer darkness") in 8:12 and later, in 25:30. Therefore, it appears that the expression

("cast...into the outer darkness") in 8:12 and later, in 25:30. Therefore, it appears that the expression![]() in Matthew 22:13 is unique, ostensibly serving the particular purpose of uniting and clustering together the three previously analysed pericopes referring to weeping and gnashing of teeth. This perhaps serves as an indirect summation prior to the final judgment discourse of the gospel (Matt. 23-25).

in Matthew 22:13 is unique, ostensibly serving the particular purpose of uniting and clustering together the three previously analysed pericopes referring to weeping and gnashing of teeth. This perhaps serves as an indirect summation prior to the final judgment discourse of the gospel (Matt. 23-25).

The parable of the faithful and unfaithful servants (24:45-51). The theme of judgment in Matthew nears its climax by means of a vivid and strange exposition of a two-part judgment of the unrighteous slave, namely the literal, post-mortem dissection of false disciples (24:45-51).

Commentators in general seem to advocate one of the interpretive schemes between the literal and metaphorical continuum, emphasizing varying differences (Blomberg 1990; Scott 1990). However, as rightly observed by Sim (2002:177), the common thread of the abovementioned interpretations of this Matthean passage is the assumption that

... the evangelist could not have intended the reference to the dissection of the servant to be taken literally. ... It seems that scholars have made decisions about the beliefs of the evangelist on the basis of their own standards and worldviews. Since the scenario presented in Matt 24:51 seems both impossible and bizarre to modern readers, it is immediately assumed that Matthew must have thought in similar fashion.

Standing in accord with such sentiments, the cutting into pieces of the wicked is not connotative of excommunication or an unfortunate mistranslation, but a literal dissection of the false disciple ("cut in two of the dismemberment of a condemned person", BDAG) (see Friedrichsen 2001:258-264), a most awful and ghastly form of punishment often alluded to in other portions of Scripture (1 Sam. 15:32; 2 Sam. 12:31; Dan. 3:29; 1 Chron. 20:3 and Heb. 11:37) (Mettius in Livy, i. 28, Horace, Sat., I. i. 99, Herodotus 7.39, and Suetonius Caligula 27).

In the light of the above, not only will the wicked weep and gnash their teeth for eternity because of judgment at the eschaton, but also the manner in which they meet their eternal destiny is equally peculiar and gruesome. With such violent language, it seems apparent that the theme of judgment in Matthew's Gospel has reached yet another climax, as Matthew reinforces this theme with greater strength and intensity.

The parable of the talents (vv. 25:14-30). Finally, in the last parable of his gospel, Matthew inserts a story in which the contrast between true disciples and their eternal reward (![]() , "come and share your master's happiness") stands in total and absolute contrast5 to the fate and eternal punishment of false disciples (25:14-30). The reference to the eschatological fate of the wicked is clear and amplified with the aid of the numerous contrasts between the true, faithful disciples and the false, faithless "disciples".

, "come and share your master's happiness") stands in total and absolute contrast5 to the fate and eternal punishment of false disciples (25:14-30). The reference to the eschatological fate of the wicked is clear and amplified with the aid of the numerous contrasts between the true, faithful disciples and the false, faithless "disciples".

In the light of the above, the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth and the theme of judgment are closely related in Matthew's Gospel. The nature and function of this link is two-fold. Firstly, the main thrust of the theme of judgment in Matthew is developed and advanced by means of the weeping and gnashing of teeth pericopes. With each occurrence of the idiom, a particular facet of the theme of apocalyptic eschatology is communicated. Secondly, each of the six passages in which the phrase occurs contributes a specific aspect to the theme of judgment in the gospels. This is especially evident in the four pericopes that are unique to Matthew's Gospel (13:36-43; 13:47-50; 22:1-14; 25:14-30). Thus, it seems that the six passages containing the idiom not only contribute specific aspects to the theme of judgment in the gospel, but the phrase also seems to appear in structurally pertinent sections, each of which increases the strength of the theme of judgment.

4. THE FUNCTION OF "WEEPING AND GNASHING OF TEETH" IN MATTHEW'S GOSPEL

After a thorough exegetical analysis of the six Matthean passages, the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth seems to serve four functions.

4.1 A mnemonic device

The phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth seems to serve as a mnemonic device by which Matthew intended to make the message of the particular parable(s) unforgettable. This tool may have been used by Jesus, since it seems that Jesus also made his teachings easy to memorize (Riesner 2004:193). Hagner (2002:xlix) adds historical context to this function:

Largely, the shape of the sayings of Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew reflects the parallelism and mnemonic devices of material designed for easy memorization. It is estimated that 80 percent of Jesus' sayings are in the form of parallelismus membrorum (Riesner), often of the antithetical variety . In its Aramaic substratum, the teaching of Jesus regularly contains such things as rhythm, alliteration, assonance, and paronomasia (see Jeremias, 20-29), and the evangelists (esp. Matthew) try sometimes to reflect these phenomena in Greek dress. All this we take to be the sign not so much of Matthew's imitation of the oral tradition (although Lohr rightly indicates that this happens) as of the actual preservation of oral tradition very much in the form in which it was probably given by Jesus.

In other words, a study of the forms of Jesus' teaching reveals that a majority of them are phrased in a way that facilitates memorization, such as parallelism, rhythm, alliteration, catchwords, and striking figures of speech (Riesner 2004:202). In fact, Riesner (p. 202) postulates that

the poetical structure of the words of Jesus made them, like the meshalim of the Old Testament prophets, easily memorizable and could preserve them intact. Even the form of the sayings of Jesus included in itself an imperative to remember them.

Therefore, it appears that such succinct phrasing exercised mnemonic functions in the memorization process (Kelber 1997:13). In the context of Matthew's Gospel, the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth is possibly the principal mnemonic catchphrase, drawing attention to a key theological emphasis, namely the eschatological reckoning of false disciples.

In the case of the first pericope (8:5-13), for example, the focus is on the theme of faith. To avoid judgment, one needs to have faith that is superior to Israel's religious leaders. France (quoted in Marshall 1977:264) alludes to this Matthean feature as he explains that the healing of the gentile's servant provides him with an excellent example of the collective application of the work of Jesus,

and he makes sure by his telling of the story and in particular by his insertion of Jesus' devastating saying that the message is not missed (Marshal 1977:269).

This functional aspect of the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth is likewise applicable to the other five pericopes, for each communicates an important message about judgment. In the second (the parable of the tares [13:24-30, 36-43]) and third pericopes (the parable of the dragnet [47-50]), the focus is twofold: Although judgment is delayed, its occasion is assured. This message is firm, clear and likely to stick in the minds of both true and false disciples (for diverse reasons). In the parable of the wedding banquet (22:1-14), the focus shifts to the reality of the strong gentile presence at the final banquet, a theme intertwined with the assured judgment of the false disciples (who view themselves as rightful heirs of the kingdom). Lastly, in the fifth (the parable of the good and wicked servant [24:45-51]) and sixth (the parable of the talents [25:14-30]) pericopes, the thematic centre of attention is on active and dynamic faithfulness ("economic faithfulness" according to Carpenter [1997]).

Therefore, the first function of the phrase is mnemonic. With the aid of the idiom weeping and gnashing of teeth, Matthew highlights the message of each parable and ensures that the message is evocative.

4.2 Prophetic anticipation

Owing to the early inclusion in the text, "8:11-12 may [also] be intended to function as a prophetic anticipation of an aspect of the larger shape of history" (Nolland 2005:257). As noted by Hagner (1993a), the destiny of unfaithful Israel (false disciples) becomes a forewarning to the church (true disciples) in subsequent judgment passages. Therefore, it seems that in each occurrence of the expression, the reader receives a vivid reminder of the dreadful fate of Israel's religious leaders (false disciples). However, Matthew appears to place such dramatic reminders strategically in his Gospel.

The first and second reminders come into view in chapter 13. The seemingly prominent seating position of the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth as the first (13:24-30 and 36-43) and last (13:47-50) parable, outside the introductory (13:1-23) and concluding (13:51-52) narratives, seems to indicate careful placement. This is especially significant from the point of view that chapter 13 is of fundamental significance to the gospel, for two reasons. Firstly, it is the chapter in which Matthew places the commencing of Jesus' parabolic teaching ministry. Secondly, it is the chapter that contains the complete alteration in the recipients of Jesus' teachings, namely from public to private (Nolland 2005; Green 2000; Boring 1995; Morris 1992; Gundry 1982).

The third reminder appears in chapter 22, where Matthew again brings the destiny of unfaithful Israel (false disciples) to the attention of his readers as a forewarning to the church (true disciples), using the parable of the wedding banquet (verses 1-14). Matthew's strategy in placing the parable of the wedding banquet (containing the expression weeping and gnashing of teeth) is noticeable. In the preceding chapters (commencing at ch. 13), the Messiah continues to perform healings, exorcisms, and miracles of every kind. This elevates the anger and aggression of his opponents to new heights. In response to such heightened hostility, Jesus proceeds to disclose this final judgment parable. The view also seems to fit with the fifth pericope (24:45-51).

Lastly, Matthew's two final strategic reminders occur within the body of the largest eschatological discourse in the Bible (outside of the book of Revelation). The parables of the good and wicked servants (24:45-51) and the parable of the talents (24:14-30) represent the two most eschatologically charged parables of the Olivet Discourse (also known as the Synoptic Apocalypse). More strategically significant in its positioning is the final weeping and gnashing of teeth parable (the parable of the talents), which Matthew uses as the final build-up narrative to the ultimate judgment pronouncement in 25:31-46 (the judgment of the nations).

Thus, it seems plausible that the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth may also function as a vivid reminder to the church. In each occurrence of the phrase in Matthew's Gospel, the reader's attention is focused backwards, to Israel, as a forewarning to the church of the impending final judgment.

4.3 A thematic intensifying device

It appears that the phrase may also function as a linguistic device, which increases the degree of emphasis or heightens the force given to a particular theme. In Matthew's case, this theme is the message of judgment. Riesner alludes to this hypothesis, explaining that Jesus often formulated strong contrast and did not hesitate to use hyperbolic speech6 and laconic phrasing as a kind of shock treatment phrase to help people see the truth (2004:201). In the light of this observation, it is likely that the expression weeping and gnashing of teeth is an eschatological theme-intensifying idiom used to express an intense attitude concerning a particular future reality. Although there are some similarities in function, this is not necessarily the same as an English intensifier, which is a word, especially an adjective or adverb, which intensifies the meaning of the word or phrase that it modifies (www.freeonlinedictionary.com). In the Matthean-biblical context, weeping and gnashing of teeth is an intensifier that intensifies a particular theme, not a word, and appears rather at the end of the phrase or sentence (possibly for heightened emphasis).

In the story of the centurion, Matthew decisively records verses 11 and 12 to make clear the future awfulness experienced by those rejected and excluded from the final reward ceremony. Matthew seemingly saw and understood that by such severe sentiments expressed with such intense language, Christ wished to communicate something of immense importance and significance.

Concerning the parable of the wedding banquet, France makes a similar observation, stating that the weeping and gnashing of teeth appears "in each case to draw out the significance of the parable of ultimate rejection" (2007:827). Therefore, it is plausible to assume that Matthew endeavoured to accomplish this by recording each instance in which Jesus uttered one of the most intimidating expressions to appear in the New Testament.

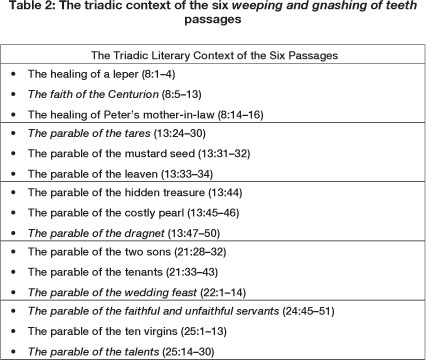

A less significant but nonetheless important observation deserves brief mention. It seems that on structural as well as grammatical levels, the theme of judgment truly comes to an absolute climax in the parable of the faithful and unfaithful servants (24:45-51) and the parable of the talents (25:14-30). Since Matthew favours groupings of three, it is noticeable that all occurrences of the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth appear within the structural framework of a larger triadic structure. The only partial exception is the parable of the tares, in which the explanation of the parable contains the phrase (vv. 36-43), and not the parable itself (verses 24-30). Nonetheless, they are closely related thematically and contextually. Table 2 illustrates this more clearly.

It may be significant to note that the concluding triadic parable cluster of Matthew's Gospel twice contains the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth.7 If this is deemed significant, it not only may strengthen the hypothesis that this Matthean phrase is a linguistic device (which increases the degree of emphasis or heightens the force given to the message of eschatological judgment), but also point to an additional structural tool to point his readers to the final intensification of the theme of judgment. No other parable cluster in Matthew's Gospel is comparable to the intensity and strength of the theme of apocalyptic judgment in this final parable cluster. Particularly, this is true in terms of the awful content and description of the final judgment. Thus, the concluding triadic parable assemblage may serve as an auxiliary reinforcement for the theme of judgment in Matthew's Gospel en bloc. In other words, with the aid of the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth, the theme of judgment has intensified with each occurrence, ending on a strikingly intense note.

The chief strand of evidence in support of the above contention is the identification of the use and function of the historical present in Matthew's final parable cluster (24:42-25:46). In an article analyzing Matthew's use and function of the historical present, Wilmshurst (2003) concludes that Matthew's usage should be understood as selective and versatile, a tool for drawing special attention to particular narrative elements for a variety of reasons (p. 269). He continues to explain (p. 286) as follows:

Because these stories [parables] are simply quoted speeches of Jesus, rather than forming part of the narrative framework, their relevance to Matthew's overall theme has to be brought out in different ways. Here, the historic present plays a crucial role of spotlighting key themes or ideas [emphases mine].

Matthew uses the historical present twice (![]() ) in his final triadic parable cluster. On the micro literary level, they appear at a fundamental point in the parable of the talents,

) in his final triadic parable cluster. On the micro literary level, they appear at a fundamental point in the parable of the talents,

as the master returns for a reckoning with his servants, and immediately following the disastrous action of the third servant in hiding his one talent (Wilmshurst 2003:286).

On the macro thematic level, the parable of the talents is the final parable in the triadic parable cluster, accentuating and intensifying (for the final occasion) the motif of judgment in Matthew's Gospel. This thematic spotlighting then becomes the final meridian of judgment in Matthew.

Seemingly, then, each parable containing the idiom weeping and gnashing of teeth signifies an intensification of the strength and significance of the theme of judgment. This may be the chief function of the idiom in Matthew's Gospel.

4.4 A literary connector

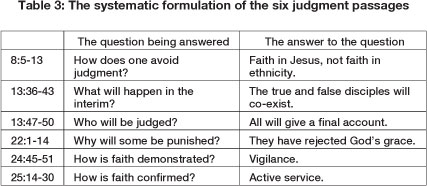

Lastly, it appears that the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth may also function as a literary connector that holds together a number of specific passages of Scripture. In Matthew's case, the phrase glues together the specific judgment passages that communicate a holistic theology of end-of-time judgment. Most major themes that are important for a correct understanding of the theme of apocalyptic judgment of the false disciples are integrated in the six passages containing the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth, as illustrated in Table 3.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the phrase ![]() is salient in Matthew's Gospel, for it communicates many of the central messages pertaining to the theme of apocalyptic judgment. The phrase is positioned in structurally relevant sections and seems to amplify in thematic potency with each occurrence. In addition, the phrase is usually uttered in the context of false disciples who stand in total contrast to the righteous in this life and the next. In terms of its function, it seems that the strategically scattered expression points the attention of readers to past unrighteousness of Israel as a nation worthy of future judgment, while guaranteeing and anchoring the thematic intensity of judgment. Likewise, the idiom makes the dreadful descriptions of the future realities of judgment unforgettable, while masterfully gluing all the fundamental characteristic of the final judgment together. Thus, with the aid of the six passages, Matthew gathers all the important aspects pertaining to the theme of judgment. Matthew's judgment theology can be formulated systematically as follows: Faith is required to avoid judgment. In the meantime, both the sons of God and the sons of the devil will co-exist, but ultimately, there is no escape from judgment, for all will stand before the Lord and give an account at the final judgment. Those who reject God's grace will be punished severely. Those who accept it will receive eternal blessings, for they understand that faith, the very essence of salvation, is demonstrated through active faithfulness, not passive neglect.

is salient in Matthew's Gospel, for it communicates many of the central messages pertaining to the theme of apocalyptic judgment. The phrase is positioned in structurally relevant sections and seems to amplify in thematic potency with each occurrence. In addition, the phrase is usually uttered in the context of false disciples who stand in total contrast to the righteous in this life and the next. In terms of its function, it seems that the strategically scattered expression points the attention of readers to past unrighteousness of Israel as a nation worthy of future judgment, while guaranteeing and anchoring the thematic intensity of judgment. Likewise, the idiom makes the dreadful descriptions of the future realities of judgment unforgettable, while masterfully gluing all the fundamental characteristic of the final judgment together. Thus, with the aid of the six passages, Matthew gathers all the important aspects pertaining to the theme of judgment. Matthew's judgment theology can be formulated systematically as follows: Faith is required to avoid judgment. In the meantime, both the sons of God and the sons of the devil will co-exist, but ultimately, there is no escape from judgment, for all will stand before the Lord and give an account at the final judgment. Those who reject God's grace will be punished severely. Those who accept it will receive eternal blessings, for they understand that faith, the very essence of salvation, is demonstrated through active faithfulness, not passive neglect.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BACON, B.W. 1930. Studies in Matthew. New York: Henry Holt. [ Links ]

BALABANSKI, V. 1997. Eschatology in the making: Mark, Matthew and the Didache. Society for New Testament Studies Monograph Series 97. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

BLOMBERG, CL. 1992. Matthew: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of the Holy Scripture (Vol. 22). New American Commentary. Nashville: Broadman Press. [ Links ]

BORING, E.M. 1995. Matthew. In: L.E. Keck (ed.). The new interpreters Bible: commentary in twelve volumes. (Nashville: Abingdon), Vol. VIII. [ Links ]

BORNKAMM, G . 1963. End-expectations and church in Matthew. In: G. Bornkamm, G. Barth & H-J. Held. Tradition and interpretation in Matthew. (Philadelphia: Westminster), pp. 15-51. [ Links ]

BRUNER, F.D. 2004. Matthew: a commentary. Volume 1: the Christ book- Matthew 1-12 (Rev. exp. ed.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

CARPENTER, J.B. 1997. The Parable of the Talents in Missionary Perspective: A Call for an Economic Spirituality. Missiology 25(2):165-181. [ Links ]

CHILTON, B. 1994. Judaic approaches to the gospels. Atlanta: Scholars Press. COPE O.L. 1989. To the close of the age: the role of apocalyptic thought in the gospel of Matthew. In: J. Marcus, & M.L. Soards (eds.), Apocalyptic and the New Testament: essays in honour of J. Louis Martyn (JSNTSS 24, Sheffield Academic Press), pp. 113-124. [ Links ] [ Links ]

DAVIES, W.D. & ALLISON, D. C. 2004. Matthew 1-7. Vol 1. International Critical Commentary. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

________. 2004. Matthew 8-18. Vol 2. International Critical Commentary. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

DEFFINBAUGH, R.L. 2004. A Leper, a Gentile, and a Little Old Lady: Matthew 8:1-17. [Online] Retrieved from: http://www.bible.org [2008, 16 March] [ Links ]

FRANCE, R.T. 1985. Exegesis in Practice: Two Samples. In: H.I. Marshall (ed.), New Testament Interpretation: Essays on Principles and Methods (Exeter: Paternoster), pp. 252-281. [ Links ]

________. 2007. The Gospel of Matthew. New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

FRIEDRICHSEN, T.A. 2001.A Note on kai dichotomësei auton (Luke 12:46 and the parallel in Matthew 24:51). Catholic Biblical Quarterly 63(2):258-264. [ Links ]

GREEN, M. 2000. The Message of Matthew. The Bible Speaks Today. Leicester: Inter-Varsity. [ Links ]

GUNDRY, R.H. 1982. Matthew: A Commentary on His Literary and Theological Art. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

GUTHRIE, D. 1996. New Testament Introduction (4th rev. ed.) Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity. [ Links ]

HAGNER, D.A. 1985. Apocalyptic Motifs in the Gospel of Matthew: Continuity and Discontinuity. Horizons in Biblical Theology 7(2):53-82. [ Links ]

________. 1993. Matthew 1-13. Word Biblical Commentary. Dallas: Word Books. [ Links ]

________. 1993. Matthew 14-28. Word Biblical Commentary. Dallas: Word Books. [ Links ]

________. 2002. Matthew 1-13. Word biblical Commentary (vol. 33A). Online edition. Dallas: Word, Incorporated. [ Links ]

HARRINGTON, D.J. 1991.Polemical Parables in Matthew 24-25. Union Seminary Quarterly Review 44(287-298). [ Links ]

HULTGREN, A.J. 2000. The Parables of Jesus: A Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

KEENER, CS.1999. A Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

KELBER, W.H. 1997.The Oral and Written Gospel. Philadelphia: Fortress. [ Links ]

LENSKI, R.C.H. 2008. The Interpretation of St. Matthew's Gospel 15-28. Minneapolis: Augsburg. [ Links ]

LONGENECKER, R.N. 1970. The christology of early Jewish Christianity. Grand Rapids: Baker. [ Links ]

MITCHELL, M.M. 1998. A Tale of Two Apocalypses. CurTM 25:200-209. [ Links ]

MORRIS, L. 1992. The gospel according to Matthew. Pillar New Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

NOLLAND, J. 2005. Matthew. New International Greek Testament Commentary. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

RENGSTORF, K.H. 1976. Βρύχω, βρυγμός. In: G. Kittel, G.W. Bromiley & G. Friedrich (eds). Vol. 1. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans), pp. 641-642. [ Links ]

RIESNER, R. 2004. Jesus as Preacher and Teacher. In: H. Wansborough (ed.), Jesus and the Oral Gospel Tradition (London: T & T Clark), pp. 185-210. [ Links ]

SENIOR, D. 1998. Matthew. Abingdon New Testament Commentary. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

SIM, D.C. 2002. The Dissection of the Wicked Servant in Matthew 24:51. Hervormde Teologiese Studies 58(1):172-184. [ Links ]

________. 2005. Apocalyptic eschatology in the gospel of Matthew. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

STANTON, G.N. 1993. A Gospel for a New People: Studies in Matthew. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

STREETER, B.H. 1924. The four gospels: a study of origins, the manuscript tradition, sources, authorship, & dates (Prepared for katapi by Paul Ingram 2004). [Online] Retrieved from: http://www.katapi.org.uk/4Gospels/Contents.htm, [2008, 16 March]. [ Links ]

TURNER, D.L. 2008. Matthew. Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Baker Books. [ Links ]

TURNER, N. 1963. A Grammar of the New Testament Greek: Vol.3. Syntax. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

VERMES, G. 1973. A historian's reading of the gospels. Philadelphia: Fortress. [ Links ]

WILMSHURST, S.M.B. 2003. The Historical Present in Matthew's Gospel: A Survey and Analysis Focused on Matthew 13.44. Journal for the Study of the New Testament 25(3):269-287. [ Links ]

1 Matthew’s increased interest in eschatology (vis-a-vis Mark, Luke, and John) is not contingent on our persuasion concerning the best explanation of gospel origins. For example, if Markan priority is assumed, Matthew added eschatological content. If Matthean priority is assumed, Mark has significantly reduced Matthew’s longer eschatological discourse.Matthew thought that Mark's apocalyptic discourse, though worthy of duplication, left out matters of grave importance ... [Matthew] almost triples it in length.2

2 Mitchell further notes two important redactional features (p. 203): “Although there are some subtle and important Matthean alterations to the early part of this apocalyptic speech by Jesus on the Mount of Olives, most noticeable is how Matthew has expanded and lengthened its ending to emphasize both the delay of the parousia and the punishment which awaits the wicked.”

3 Matthew authorship is assumed in this study, without forming a judgment as to which Matthew is meant.

4 The five-discourse hypothesis, championed by Bacon B W (1930:82, 265-335) identifies Matthew’s Gospel as designed or built around five blocks of teachings (chs. 5-7; 10; 13; 18 and 23-25). Each sermon is preceded by a contextual narrative and ends with the phrase ![]() (“when Jesus had finished saying all these things”, NIV) in 7:28; 11:1; 13:53; 19:1 and 26:1.

(“when Jesus had finished saying all these things”, NIV) in 7:28; 11:1; 13:53; 19:1 and 26:1.

5 ![]() (“come and share your master’s happiness”). Deffinbaugh (2004:n.p.) makes the point, “The ‘joy of the master’ must, in some way, equate to enjoying the bliss of heaven, with our Lord. ‘Weeping and gnashing of teeth,’ in outer darkness must, on the other hand, involve spending eternity without God, and without joy” (see also Hultgren 2000). The reference to the eschatological fate of the wicked is clear, amplified with the aid of the numerous contrasts between the true, faithful disciples and the false, faithless disciples.

(“come and share your master’s happiness”). Deffinbaugh (2004:n.p.) makes the point, “The ‘joy of the master’ must, in some way, equate to enjoying the bliss of heaven, with our Lord. ‘Weeping and gnashing of teeth,’ in outer darkness must, on the other hand, involve spending eternity without God, and without joy” (see also Hultgren 2000). The reference to the eschatological fate of the wicked is clear, amplified with the aid of the numerous contrasts between the true, faithful disciples and the false, faithless disciples.

6 Although Jesus did make use of hyperbolic speech techniques, the phrase weeping and gnashing of teeth is by no means a hyperbole, but rather an eschatological prophecy of future judgment of the wicked.

7 For a convincing argument for the thesis that the parable of the faithful and unfaithful servants (24:45-51), the parable of the ten virgins (25:1-13) and the parable of the talents (25:14-30) ought to be viewed as a single unit (the three major polemical parables of chapters 24 and 25), see Harrington (1991:287-298).