Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.31 n.2 Bloemfontein Jan. 2011

Spiritual abuse under the banner of the right to freedom of religion in religious cults can be addressed

SP Pretorius

SP Pretorius, UNISA. E-mail: Pretosp@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The international endeavour to afford the right to freedom of religion to all world citizens is essential. This right ensures that people can choose their own religion and freely participate in the practice thereof. Although the conventions on religious freedom prohibit the use of unethical coercion in order to proselytise and retain members, the enforcement of this prohibition is problematic. Underlying psychological processes that induce members in cults to engage in radical behaviour changes cannot be proved without reasonable doubt in any legal action. The conclusion reached in this article is that although - on paper - the right to religious freedom ensures freedom in the sense that people can choose their religion, it cannot ensure that worship in any religion is a voluntary act on the part of the participants. On the one hand, religious freedom has opened the world of religion to people; but at the same time, it has also created a vague, or "grey" area where abuse can flourish under the banner of so-called "freedom". Freedom that is not clearly defined can lead to anarchism. Abuse in religious cults can be addressed by cultivating public awareness through the gathering and distribution of information on the abusive practices of these groups.

Keywords: Freedom of religion, Spiritual abuse, South African constitution

Trefwoorde: Vryheid van godsdiens, Geestelike mishandeling, Suid-Afrikaanse grondwet

1. INTRODUCTION

As a result of the broad definition of religion, as well as of religious and cultural diversity, the concept of religious freedom has lost its precision and clarity, in that its ambit has become vague. The consequence is that nowadays, the qualification of what counts as a religion, or a religious act, is much more linear in nature. A negative result of this lack of clarity in the demarcation of the religious domain is that when other rights are infringed or negated as a result of the dynamics or characteristics of a religion, this factor is often simply ignored.

Robinson (2004:xix) reports that, during the Millennium Peace Summit of Religions and Spiritual Leaders which opened on 28 August 2000, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights affirmed the importance of dialogue between the world religions in the pursuit of the fundamental objective of making the world a more peaceful place. Conversely, bigotry, prejudice and discrimination will lead to conflict and war. However, each religion should bear the responsibility of ensuring that its own internal practices are not discriminatory on the grounds of gender, race or class. Although the international community needs to guarantee freedom of religion, even for minorities such as new religious movements, it is also necessary to guard against invoking religious freedom as a pretext for the furtherance of purposes that are contrary to human rights (Amor 2004:xvi).

Emphasis is placed on the freedom to express or practise one's religion. But what about the underlying dynamics which, in some religious groups, contribute to radical behaviour on the part of individuals, thereby violating other basic human rights? This article will attempt to demonstrate that the right to freedom of religion does not necessarily protect people against unethical coercion processes that are applied in religious cults. Measures to address the spiritual abuse that is perpetrated in these groups, especially in South Africa, will also be proposed.

2. RELIGION AND RELIGIOUS FREEDOM

Religion, or a belief system, is central to the daily lives of millions of people around the globe. Men and women have worshipped a god - or gods - ever since they became cognisant of a need to do so. Through a relationship with God, or by means of a religion or belief system, people find a referential framework for the meaning of life. This stimulates and shapes their sense of identity, promoting harmony, as well as care for fellow human beings and the environment. Religion is therefore strongly connected with personal identity formation and group belonging (Naber 2000:1). But how is religion defined?

2.1 Religion defined

Because it crosses so many different boundaries in human experience, religion is difficult to define. Many attempts have been made to do so, however; and although every theory has its limitations, each perspective contributes to our understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Definitions of religion tend to be characterised by one of two shortcomings: they are either too narrow, thereby excluding many belief systems which most would regard as religious; or they are too vague and ambiguous, suggesting that virtually anything that resembles a set of beliefs is a religion (Cline n.d:1).

A good example of a narrow definition is the common attempt to define "religion" as "belief in God," effectively excluding polytheistic and atheistic religions, while including the kind of theism that is endorsed by persons who have no religious belief system.

William James (1961:42) defined religion as

the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine.

Such a definition is limited, since it does not take account of the fact that religion is more than affect, and does not merely refer to what people do in their solitariness. Religion is also a social phenomenon, as Newsman (1972:3) points out - it is something that people do in groups. Eliade (1963:30), the Roman Catholic historian of religions, indicates that there is another approach to religion, apart from the psychological or sociological perspective. He indicates that patterns or forms of religious expression must also be investigated. The sociologist, Durkheim (1968:47), linked religion to the concept of "church":

A religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things. These beliefs and practices unite people into one single moral community called a Church.

Religion can be defined as a set of beliefs concerning the origin, nature, and purpose of the universe - usually in terms of a creative act by a superhuman agency or agencies - typically involving devotional and ritual observances, and often including a moral code governing the conduct of human affairs. More concisely, religion is a specific fundamental set of beliefs and practices generally agreed upon by a number of persons or sects, for example, the Christian or Buddhist religion. Religion can also refer to the body of persons adhering to a particular set of beliefs and practices ( Dictionary.com. n.d.).

According to a recent edition of the Oxford dictionary, religion is a belief in the existence of a supernatural ruling power - the creator and controller of the universe - who has endowed man with a spiritual nature which continues to exist after the death of the body. Religion appears to be a simple phenomenon on the surface; but in reality, it entails a very complex system of ideas that comprise the fundamental principles on which many people base their lives.

The word religion is sometimes used interchangeably with faith or belief system. However, religion differs from private belief in that it has a public aspect. Most religions are characterised by organised behaviours, including clerical hierarchies; a definition of what constitutes adherence or membership; congregations of lay persons; regular meetings or services for the purposes of prayer, or the veneration of a deity; holy places (either natural or architectural); and/or scriptures. The practice of a religion may also include sermons, commemoration of the activities of a god or gods, sacrifices, festivals, feasts, trances, initiations, funerary services, matrimonial services, meditation, music, art, dance, public service, or other expressions of human culture (Wikipedia n.d.).

Aspects of religion include narratives, symbolism, beliefs and practices that are supposed to give meaning to the practitioner's experiences of life. Whether this meaning is centred on a deity or deities, or on an ultimate truth, religion is commonly manifested by the practitioner's prayers, rituals, meditation, music and art, among other things, and is often interwoven with society and politics.

Religion may focus on specific supernatural, metaphysical and moral claims about reality (the cosmos and human nature), which may find expression in a set of religious laws and ethics and a particular lifestyle. Religion also encompasses ancestral or cultural traditions, writings, history and mythology, as well as personal faith and religious experience. The development of religion has assumed many forms in diverse cultures, with continental variations.

Religion is often described as a communal system that fosters the coherence of beliefs focusing on a system of thought, or an unseen being, person, or object that is considered to be supernatural, sacred, divine, or of the highest order of truth. Moral codes, practices, values, institutions, traditions, rituals and scriptures are often traditionally associated with the core belief; and these may overlap, to some extent, with concepts in secular philosophy. Religion is also often described as a way of life or a "life stance" (Wikipedia, religion n.d.).

On the basis of the foregoing, and for the purposes of this study, religion is defined as belief in, and worship of a god or gods; or, in more general terms, as a set of beliefs explaining the existence of, and giving meaning to the universe, usually involving devotional and ritual observances, and often including a moral code governing the conduct of human affairs, as well as organised behaviours such as clerical hierarchies, rules for adherence or membership, regular meetings for worship or prayer, holy places, and/or scriptures. Religion is distinguished from private belief in that it has a public aspect that unifies people into a religious community.

For the purpose of this study, the focus will fall on religion, since religious cults and sects are generally structured and organised in the same way as religious communities, and are usually classified as such.

It is unfortunately true that from the earliest times, religion has been both a divisive and a cohesive force in society. Spiritual beliefs have been the inspiration for immense good - but also the driving force and justification for mass persecutions, intolerance, and abuse of the rights of others (Knights 2007:1). Thus, the importance of the protection afforded by freedom of religion for society as a whole, and minorities in particular, is undeniable.

2. 2 International conventions on religious freedom and the South African Constitution

After the 1945 San Francisco Conference and the establishment of the United Nations, the international community - not convinced of the validity and genuineness of the assertion of collective and group rights - shifted its emphasis from protecting collective and group rights to affording protection to individual persons on the basis of individual rights and non-discrimination. Persons whose rights were violated or jeopardised because of a group characteristic - whether race, colour, religion, ethnic or national origin, culture or language - would henceforth be protected purely on an individual basis (Lerner 2004:66).

Only a few important conventions will be discussed. The first United Nations instrument to address the subject of religious freedom was the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The seminal article 18 of the Declaration greatly influenced the 1966 Covenant on Economics, Social and Cultural Rights, the 1966 Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the regional treaties and the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief (Lerner 2004:67). The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) (formally entitled the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms), an international treaty to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms in Europe, was drafted in 1950 by the then newly formed Council of Europe, and came into effect on 3 September 1953 (Wikipedia, European Convention on Human Rights n.d.).

Article 18 (Universal Declaration of Human Rights) reads:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

Article 9 - Freedom of thought, conscience and religion (ECHR) reads:

1. Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief, in worship, teaching, practice and observance.2. Freedom to manifest one's religion or beliefs shall be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of public safety, for the protection of public order, health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

Considered in their entirety, articles 18 and 9 address four main issues:

1. They guarantee the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion in general. This is the right to believe or not to believe. The term "belief" follows the term "religion", and should be interpreted strictly in connection with the word "religion".

2. They address the issue of conversion and religious proselytising. With the drafting of the 1966 Covenants and the 1981 Declaration, however, proselytising activities became controversial. Such activities may sometimes involve the infringement of rights such as privacy, as well as interference with the integrity of some group identities - for example, when ethnicity is a prominent factor - and may even be illegal. Such illegal acts may include the abuse of conversion and proselytising rights, coercion of "captive audiences" and the use of improper enticements.

3. They address the manifestations of religious freedom. Unlike freedom of thought and conscience, which can only be limited by complicated psychological techniques that influence the human mind, manifestations of religious rights can sometimes be a problematical issue, because these rights are more likely to be negated (Lerner 2004:68).

4. The freedom to manifest one's religion or beliefs is subject only to limitations that are prescribed by law, and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of public safety, for the protection of public order, health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

An area that needs to be addressed is referred to in paragraph 2 of article 9, pertaining to cases where an infringement of other rights of the person occurs in the exercise of the right to freedom of religion. Paragraph 2 of article 9 refers to limitations prescribed by law, which ensure that the right to freedom of religion is not an absolute right. It is a right that needs to be balanced in a democratic society, in order to ensure that it does not violate other fundamental rights. Clashes between conflicting rights can occur in any religion; but the focus of this study is on cults. Article 9 addresses a tendency in terms of which the manifestations of religion or belief are not required to adhere to the protection of other rights.

In terms of the South African Constitution, everyone is afforded the right to freedom of religion (section 15), as well as the freedom to practise a particular religion by participating in the rituals, and abiding by the tenets, of that religion (section 31(1)(a)). However, it is stipulated that the practices and rituals of the religion, whether physical or emotional in nature, may not be inconsistent with the provisions of the Bill of Rights.

The right to freedom of religion comprises two important elements. Firstly, it refers to the freedom of a person to choose his or her religion (section 15(1)). Secondly, this right makes provision for a free and voluntary act of will on the part of the individual (section 15(2)(c)) when participating in the rituals and practices of the religion (section 31(1)(a)). No person should be forced in any way, either by means of physical strength, or through emotional or psychological duress, to participate in or attend any religious ritual. The application of such coercion is inconsistent, not only with section 15(2)(c), but also with section 18, pertaining to the right to freedom of association.

The elements of the right to freedom of religion can be summarised as follows:

• A person has the right and freedom to choose any religion (section 15(1)).

• Participation in a religion must be a free and voluntary act of will on the part of the person (section 15(2)(c)).

No unethical method or coercion may be used in order to induce or force any person to participate in a religion. Neither may any right be exercised in a manner inconsistent with any provision of the Bill of Rights (section 31(2)).

The freedom of religion is not an absolute freedom. It must function within the boundaries of the other basic human rights and common law, otherwise there will be clashes between competing rights.

2.3 Complications relating to the application of the right to freedom of religion

It is evident from the reports issued by the United Nations on the protection of the right to freedom of religion that serious attempts are being made to afford this freedom not only to society in general, but particularly to minority groups. From the report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, it is clear that the issue of sects and new religious movements1 is complicated by the fact that international human rights instruments provide no definition of the concepts of "religion", "sect" or "new religious movements". Added to this legal dimension is the confusion regarding the term "sect", in particular. This term initially referred to a community of individuals comprising a minority within a religion, who have dissociated themselves from the main body of that religion. Currently, it often has a pejorative connotation, with the result that it is frequently regarded as synonymous with danger. It is important to consider the phenomenon of sects and new religious movements objectively, in order to avoid two pitfalls, namely the infringement of the freedom of religion, and the exploitation of the freedom of religion and belief for purposes other than those for which it has been recognised (United Nations General Assembly Human Rights Council 2006:par.44). It should further be borne in mind that the scope of application of freedom of religion, in terms of the manifestations of this freedom, may largely be subject to such limitations as are prescribed by law, and as may be necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals, or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.

The absence of a definition of the concepts of new religious movements and sects (where such a definition could serve as a human rights instrument), as indicated in the report above, results firstly in a limited comprehension of the composition and dynamics of such groups. Secondly, it complicates the application of the right to freedom of religion in these particular groups. "New religious movements, sects and cults" will be addressed later.

2.4 The freedom to manifest one's religion or belief

It is generally accepted that the manifestation of religion must be a voluntary act on the part of the individual. Article 9 of the ECHR and section 15(2) (c) of the South African Constitution refer to the freedom to "manifest his/her religion or belief". In both cases, a broad interpretation seems to have been attached to the words "religion" and "belief" to include not only religious and non-religious beliefs, but also all kinds of minority views. For example, veganism (strict vegetarianism) or communism may also be regarded as a "belief" falling within the ambit of article 9. This does not mean that every individual opinion or preference is a religion or belief. The concept is more akin to that of religious and philosophical convictions denoting "views that attain a certain level of cogency, seriousness, cohesion and importance" (Vermeulen 2000:21).

With regard to the manifestation and practice of religion or belief, the European Commission has endorsed a more restrictive interpretation. This became evident in the Arrowsmith case2. Arrowsmith claimed that she was entitled to distribute leaflets to troops in the British army camp, in which she advocated the view that they should not serve in Northern Ireland, as article 9 of the ECHR gave her the right to express her pacifist belief in this practice. The Commission argued that a strictly subjective criterion is not admissible. The term "practice", as employed in article 9.1, does not cover every act which is motivated or influenced by a religion or belief. An objective criterion was applied by the Commission, namely that when the actions of individuals do not actually express a particular belief, they cannot be considered to be protected by article 9.1, even when they are motivated by the belief. The Commission concluded that, since the pamphlets did not express pacifist views, the applicant did not manifest her belief in terms of article 9, and therefore could not invoke this provision (Vermeulen 2000:21).

Another case that illustrates the difficulty involved in determining possible restrictions on the manifestation of religion is that of Schuppin v. Unification Church.3 Parents of a cult member of the Unification Church alleged that their daughter was forced to work in "compulsory service." The parents claimed that the cult leadership used constant threats and fear to coerce their daughter to sell merchandise for the cult. The lawsuit failed, however, because the parents were only able to report mental restraint, and not physical force, on the part of the cult to compel the member to stay within the cult (Lucksted & Martell 1982:6).

The important factor that can be discerned from these rulings is that protection of the right to freedom of religion does not cover every act that may result on the grounds of a member's interpretation of his or her particular belief system. On the other hand, the ruling in Schuppin v. Unification Church also implies that protection of the right to religious freedom does not extend to any or every religious act or practice within a specific religious group, especially if such an act or practice contradicts common law and is not in the interest of public safety, order, health, or morals, or infringes the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.

2.5 The balancing of competing rights

The primary focus of the qualified right to freedom of religion referred to in article 9 of the ECHR is that of effectuating a balance between the rights of the victim in terms of the ECHR, and the obligations and interests of the state. Knights (2007:65) indicates that a secondary focus of this right is to consider the interests of the individual as opposed to those of the religious group, by considering the competing interests of children and parents. There are a number of areas where competition between substantive rights will arise. The balancing of freedom of religion in a society (article 9) may involve considering other competing ECHR rights, including freedom of expression (article 10), freedom of association (article 11), the right to peaceful enjoyment of possessions (article 1, protocol 1), privacy and family life (article 8), the right to marriage (article 12) and freedom from torture (article 3). The addressing of competing rights in the exercise of religious freedom may be affected by the relative importance ascribed by society to the religion in question. In practice, decisions in particular cases are highly "fact-specific" and revolve around a number of factors, including the position of religion in society as a whole, the nature of the competing interests, the relative numbers of individuals affected on each side of the dispute, and the extent of interference in the rights of the respective parties (Knights 2007:66). The ECHR is mainly concerned with the rights of individuals, although it is accepted that groups such as religious organisations can also be defined as victims in some instances. There are cases, however, where the interests of the group, as articulated by the leadership of the organisation, may conflict with the rights of individual members. The rights of women and children are of particular concern, as many religious groups tend to be dominated by men, masculine values, and a patriarchal hierarchy (Knights 2007:73).

One area where the need to effectuate a balance frequently comes to the fore, pertains to the boundaries between the right to freedom of religion and the right to freedom of expression. In religious cults, the right to freedom of religion competes with - and even overrules - other basic human rights, such as freedom of expression and freedom of association. The aim of the balancing of competing rights is to ensure that one right does not acquire a position of supremacy over any other right. Any person, in whatever setting or position, should enjoy the freedom to all rights equally. What complicates the balancing of competing rights in the context of cults is the fact that underlying psychological processes that are present in the proselytising and retaining of members, as well as a certain subculture and group identity, seem to contribute to a belief in the supremacy of the right to freedom of religion above other rights. Members renounce other rights, such as freedom of association and freedom of expression, in the belief that both of these rights are superseded by, and secondary to, the right to religious freedom. Furthermore, the renunciation of these rights is viewed as a "sacrifice" for the common good.

3. NEW RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS AND CULTS

It has become evident, on the basis of the report of the United Nations, that the concept of "a new religious movement" is in need of further clarification, in order to address the issue of freedom of religion (United Nations General Assembly Human Rights Council 2006). The word "cult" also warrants clarification.

3.1 New religious movements

A new religious movement (NRM), in its broadest sense, refers to a religious community or an ethical, spiritual, or philosophical group of modern origin. NRMs may be novel in origin, or they may be derived from a broader religion, such as Christianity, Hinduism or Buddhism. In the latter case, NRMs are distinct from the pre-existing denominations. Scholars studying the sociology of religion have almost unanimously adopted this term as a neutral alternative to the word "cult". NRMs vary in terms of leadership, authority, concepts of the individual, family and gender, teachings and organisational structures. These variations have presented a challenge to social scientists in their attempts to formulate a comprehensive and clear set of criteria for classifying NRMs. Currently, the endeavour to reach consensus on definitions and boundaries is ongoing (Wikipedia, new religious movements n.d.).

In order to qualify as a "new religious movement", such a group should be both of recent origin, and different from existing religions. No consensus has been reached regarding the term "new". Some authors use World War II as the dividing line to determine which movements are "new", whereas others define all such movements that came into being after the advent of the Baha'i Faith (in the mid-19th century) as "new". Different opinions also exist in terms of the second criterion for classifying NRMs, namely that they are different from existing religions. In the view of some authors, the term "difference" applies to a faith which, although it may be regarded as part of an existing religion, has met with rejection from the proponents of that religion for not sharing the same basic creed, or which has declared itself to be separate from the existing religion - or which even claims to be "the only right" faith (Wikipedia, new religious movement n.d.).

The concept "new religious movements" refers to loose affiliations - based on novel approaches to spirituality or religion - to communitarian enterprises that demand a considerable amount of group conformity, and a social identity that separates their adherents from mainstream society.

One example that can be identified within the broad range of such movements is that of what can be described as religious cults. The usage of the word "cult" resulted in a debate in the 1970s. The term acquired a pejorative connotation, and was subsequently used indiscriminately by lay critics to disparage faiths whose doctrines they saw as unusual or heretical. The inclusion of cults in the concept of "new religious movements" does no justice to the true composition of cults, and has the effect of classifying harmful groups in the same category as harmless groups. A justification for the word "cult" follows.

3.2 Justification for the use of the word "cult"

The usage of the term "new religious movement" as a substitute for "cult", as indicated above, is problematic for the following reasons:

The term "new religious movements" has been introduced as a substitute for the word "cult", since "cult" carried negative connotations linked to the images of slaughtered men, women and children at Jonestown, as well as the slaughter of followers of David Koresh in Waco, Texas - in contrast to the impression of a movement with a small harmless devoted following.

The way in which the word "cult" is used by society in general, differs from the way in which it is used by cult experts, or by behavioural psychologists or sociologists, or in religious history. When the 1913 Webster definition of a "cult" is compared to the more detailed Merriam-Webster definition, it is evident that numerous impressions created by scholars, as well as news media, have added connotations to the word "cult" which were not initially present in the root word. The work of scholars such as Lifton (1989), Singer (1995) and Hassan (1988), identifying the element of mind control in cults, resulted in some objections being raised regarding the notion of mind control, and it was pointed out that this aspect is not even included in the dictionary definition. However, when the topic of cults is raised, it is immediately associated with mind control; and there is a concomitant fierce division of opinion concerning the reality of the phenomenon (Clark 1997:2).

The dynamics of cults resulting in radical behaviour on the part of followers is called into question. How can a cult leader kill with words as surely as with a weapon? Does he do this in the same way that gangs induce people to kill for the sake of gaining control over a few blocks of a ravaged slum? Is it done in the same way that world leaders convince the population that the way to peace is to build enough weapons to destroy the planet, and then point them at each other? Through delusion, ludicrous belief systems about anything can be cultivated. Delusion and ludicrous belief systems are not only a cult phenomenon, but also a phenomenon affecting the broader society (Clark 1997:3). However, if the generalisations in this regard are put aside, a cult can be described as a religious group that commonly follows a radical leader (Mather & Nichols 1993:86) who is believed to have a special talent, gift, knowledge or calling (Singer & Lalich 1995:7). These groups have radically new religious beliefs and practices that are frequently perceived to be threatening the basic values and cultural norms of society at large (Mather & Nichols 1993:86; Hexham 1993:59), and which employ sophisticated techniques designed to effectuate ego destruction, thought reform and dependence on the group (Bowker 1997:247). Furthermore, such groups aim to extend and promote their mission independently of their members' previous relationships with family, friends, religion, school or career. They employ beliefs, practices and rituals which reinforce their values and norms (MacHovec 1989:10). The practices of these groups are centred on the goals and desires of the group's leader or leaders, to the exclusion of other activities (Clark 1997:3).

3.3 Why cults cannot be classified as new religious movements

The term "new" signifies "recently formed" - this notion evokes an impression of New Age groups and other recent phenomena such as the consideration given to many non-traditional and non-Western belief systems, for instance the rise of Eastern mysticism among Americans. The word "new" in the term "new religious movements" implies that there is something which separates recently-developed religious movements and cults from movements that have existed for some time. This is not the case. Except for some further sophistication of the methods and dynamics involved in the controlling of members, no fundamental changes in the general structures of religious movements have occurred. "New" further signifies a distinction between old and new. It creates a specific impression concerning groups such as the Moonies, the Church of Scientology, the Christian Coalition, the loosely affiliated and loosely structured congregations of those who share Eastern religious beliefs, new denominations of established religions, the Hare Krishnas and any religious movement that is "new". The impression created is that there is something in the novelty of these groups that separates them from other groups, endowing them with a shared distinction that makes it meaningful to speak of new religious movements (Clark 1997:4). The word "new" does add a useful distinction, in that it refers to the stage of development of religious movements. Unfortunately, at the same time, it lumps together cults, denominations, loosely affiliated networks of people with similar beliefs, and other groups which are tenuously related at best.

The term "religious" carries connotations of churches, clergy, charitable acts, noble self-sacrifice, freedom of belief and action, and the right to free assembly, one's notion of God, hierarchies, tax exemption, martyrdom, persecution and holy wars. This term limits the scope of the concept of "new religious movements", and once again destroys a functional distinction that is applicable to groups which share nearly identical practices, nearly identical contradictions in their doctrines, nearly identical thought stopping techniques which give one pause for thought when confronted with a different viewpoint, and nearly identical methods of recruitment and expansion. It furthermore creates a false impression that religious belief is a defining characteristic of a motley set of groups - a set which is also defined by novelty - and pointlessly links a set of disparate groups on the basis of irrelevant and arbitrary criteria (Clark 1997:5). The word "religious" almost immediately evokes a positive impression of the set of groups. Once a group is classified as religious, other aspects of the group are diminished in importance, and notions of freedom of religion are extended to cover such movements despite their written doctrines, their documented behaviour and their methods of recruitment and expansion.

The word "movement" also contains many implications, and carries both a positive and a negative connotation. It can be applied to any number of phenomena. One connotation of the word pertains to a spontaneous decision based on the knowledge that there are others sharing a belief. This tends to create the impression of a loose coalition of individuals striving towards a common goal. However, a deliberate recruitment process is in stark contrast to a movement, in terms of the positive connotation associated with the latter.

The words "new", "religious" and "movement" convey a positive impression, implying that there is something positive and spontaneous about being recruited into a cult. They also imply that this process is similar to that in which someone takes action in collaboration with others, on the basis of their pre-existing beliefs and knowledge. The two processes are actually widely divergent, however.

Cults thus cannot be categorised as new religious movements. The word "cult" makes an important distinction between harmless and harmful religious groups.

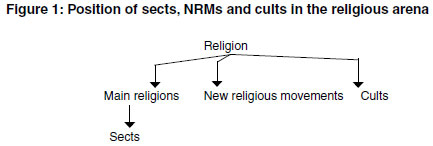

See Figure 1 for an elucidation of the position of sects, NRMs and cults in the arena of religion.

4. SHORTCOMINGS OF THE PROTECTION OF THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN RELIGIOUS CULTS, AND MEASURES TO ADDRESS THESE SHORTCOMINGS

As a result of religious and cultural diversity, the concepts of religion and freedom have lost their precision and distinctiveness. Nowadays, as a consequence, there is no longer clarity as to what counts as a religion or a religious act. Is Satanism a religion? Is the Scientology Church a church? Can the use of drugs in a cultural ritual be regarded as a manifestation of a religion? Is the wearing of headscarves by women an act of Muslim faith? Does female circumcision fall within the ambit of the freedom of religion (Vermeulen 2000:23)? Is the smoking of marijuana - or "ganja", as it is more commonly known - viewed as a religious ritual in the worship practices of the Rastafarian movement? The above all refer to visible manifestations.

Although the intention of the right to freedom of religion in general across the globe is good, and although this endeavour is necessary, in that it aims to afford equal rights and freedom to all, one challenge remains. How will the individual freedom of members of religious cults be ensured? Religious freedom needs to be endowed with an additional facet: it should not only ensure that individuals have the freedom to worship, but also - and more so that the worship will be conducted in the service of religion, and not of religious leaders with ulterior motives and hidden agendas that lead to the violation of other human rights. What measures can be put in place to ensure that other rights of individuals in religious settings are not violated?

The following questions illustrate the magnitude of the above challenges in terms of the underlying aspects, dynamics and processes generally encountered in religious cults, which need serious consideration within the context of the debate surrounding the right to religious freedom:

• What psychological/emotional aspects that are imbedded in a religion or religious group are likely to lead to expressions of that religion that clash with other rights of the particular individual, as well as those of other individuals? An example is indoctrination processes that eventually persuade believers to become involved in a "holy war".

• What underlying persuasive processes will ultimately influence members of a particular cult to break all ties with their beloved family and give up their right to freedom of association?

• What dynamic is at work when followers of a religious leader do not bury a loved one who has died, because the leader has instructed them to refrain from doing so, in order to enable him to raise the dead person a few months later?

• What about children who are born and raised within a particular religious group and who, as a result of the dynamics and culture of the particular group, are never exposed to any other view? Will they really possess the ability, when they come of age, to make decisions that are free of the influence that has been wielded by the group for many years?

• What invisible processes are at work when followers of a cult commit suicide at their leader's behest?

It should be clear by now that the psychological/emotional aspects of religion cannot be underestimated, and may lead to certain manifestations and behaviour that clash with other basic rights of the members. Dealing with the outward expression of such processes merely amounts to treating the symptoms, and not the cause. A more important question, then, is: what causes members to act in this way? This aspect links up, in a concrete manner, with paragraph 2 of article 18 of the International Convention on Religious Freedom, as well as section 15(3) of the South African Constitution, which refer to unethical methods and illegal acts that may include the abuse of conversion and proselytising rights, coercion of 'captive audiences' and the use of improper enticements.

Unethical or illegal methods do not only include visible acts or processes, but also subliminal psychological and emotional influences. These can also be referred to as the unwritten rules, invisible dynamics or doctrines of some religious groups. The case studies of Arrowsmith and Schuppin v. Unification Church, discussed above, clearly demonstrate this point. No clear doctrine determined the members' specific actions or expressions. Members most probably believed their actions to be in keeping with their own extended interpretation of the requirements of their faith. This possibly also demonstrates the power of the underlying psychological/emotional process that forms the basis of a particular belief system contributing to the view that certain actions and expressions fall within the ambit of that religion. A good example of this occurs when somebody incorrectly finishes the sentence of another person, assuming that he knows what the other person intended to say. This illustrates the wide - and vague - field of definition afforded by the term "freedom", which allows for almost any interpretation of a particular belief.

The case of the followers who - at the instruction of their spiritual leader - abstained from burying a loved one,4 suggests that the dynamics in this particular case superseded the logical thinking processes of the followers. Furthermore, the impact of such an action, in terms of the negation of public safety, order and obedience to common law, is also considerable. In this case, which involved the late Mr Paul Meintjies and his loved ones, the human dignity that forms the foundation of human rights was denied.

The word "freedom" has wrongfully acquired a connotation which is taken to imply that, within the sphere of religion, no limitations exist. Freedom of religion and the right to express one's religion supersede other rights; and in certain religious groupings, this is often justified by phrases such as "God requires everything" or "man has no rights". The actions of these groups which ignore other fundamental rights - are justified by the explanation that the concept of human rights is a secular notion, which should not be adhered to by true followers of God.

Cults function with almost total freedom, and without any restrictions especially when their members are isolated as communities on tracts of land that are out of sight of the general public. This isolation, without much - if any - contact with other religions or religious groups, must surely raise some questions about the freedom of members in terms of the right to freedom of religion. In addition, what measures are in place for the people in isolation, in order to ensure the freedom to exercise their other basic human rights? In contrast to other, mainstream religions, which have some measures in place to guide and correct their religious denominations and activities, religious cults have no such measures.

The challenges relating to religious cults in terms of their harmful practices firstly include the establishment of a sound basis of information on these groups. Misinformation or inadequate information in this regard could easily lead to public hysteria and a generalisation that might ultimately result in the stigmatisation of all alternative groups. Such a generalisation would reduce and seriously impact on the success of any attempt to investigate the practices of such groups, with a view to establishing an accurate perspective in determining possible threats to the community. South Africa is in need of methods of observation to monitor these practices and to gather information on the concerned groups, in order to establish an informed understanding of their practices. This information can then be made available to the general public. Secondly, in conjunction with the gathering and distribution of information, the establishment of a framework of communication with these groups is important. Some groups in South Africa that are suspected of spiritual abuse are antagonistic towards any attempts by outsiders to investigate or engage in dialogue about the alleged abuse. Attempts by an organisation in South Africa, known as RIGHT ("Rights of Individuals Granted Honour To"), to communicate directly with a particular group resulted in the closing down of the website of the organisation RIGHT. Assistance provided to the family of a cult member at a later stage led to the closing down of the same website for a second time.

In South Africa, there are only a small number of informed organisations in this regard. These organisations are comprised of a number of members, including professionals such as psychologists, theologians and legal experts, as well as ex-members of cults. Although these bodies comprise non-governmental organisations, no relationship with the government, or other organisations such as the Human Rights Commission, has been established. One reason for this may be that the seriousness of the matter has not yet been realised in South Africa. Even with regard to the early stages of the development of these groups, South Africa could certainly learn some valuable lessons from Europe regarding how to deal with such groups, not only in terms of ensuring the right to freedom of legitimate religious groups, but also, at the same time, with a view to identifying possible abuse that is perpetrated by some groups under the banner of the right to freedom of religion. As a member state of the United Nations, South Africa should also adhere to the recommendations pertaining to the establishment of information centres (Council of Europe report 1999:7).

Non-governmental educational/information centres, which could perhaps be called New Religious Movement Information Centres, should be es-tablished, not only to inform the general public and to educate young people, but also with the aim of bringing the threat of harmful practices in susceptible environments to the attention of government and other stakeholders. Such centres could also enter into co-operative agreements with the government, in order to ensure that religious freedom is upheld in such environments.

5. CONCLUSION

Although the intent of the convention on religious freedom is to ensure the freedom to choose one's own religion, as well as the right to participate in the rituals and expressions of the particular religion, the right to freedom of religion can never be an absolute right. Freedom entails being free to do anything that does not harm another person. This resonates with the golden rule of the Jewish-Christian tradition: "What you don't want to be done to yourself, don't do it to someone else" (Houtepen 2000:43). The challenge is that of how to ensure that subliminal and psychological processes are taken into account in the affording of the relevant freedom, while at the same time ensuring that individuals are protected from any undue influence and coercion that may be applied to establish certain behaviour that could be mistaken for acts of their own free will.

Although a shift has been made by the international community from protecting collective and group rights to protecting individuals on the basis of individual rights and non-discrimination, discrimination still seems to be present in another form, namely that of a group culture, or "cult culture", which is encountered in cults. This is a subtle culture that aims to change behaviour without the knowledge of the person, and which is presented as the ultimate form of worship, while ignoring the other rights of individuals. Although scholars agree that cults do place pressure and constraints on their members, there is no non-contentious way of establishing whether a person has been forced to believe something against his or her better judgement (Barker 2004:584).

In the light of the foregoing, it must be concluded that the right to freedom of religion (as it is currently formulated) does, in fact, fail believers, in the sense that it cannot provide a guarantee against any spiritual abuse. This right does not protect individuals from unethical influences. Although, on the one hand, it protects the rights of minority groups such as religious cults, it does not cover the infringement of the other rights of the people who are influenced by these cults. Although, according to articles on religious freedom, unethical coercion is prohibited internationally as a method of proselytising, no remedial measures are in place other than legal processes - which are extremely difficult to implement, because in order to effectuate any redress, it must first be proved beyond all reasonable doubt that these coercive practices are present in cults. Freedom of religion can easily be misused in order to entrap people in a system and culture that is abusive. In order to establish awareness regarding the possible abuses perpetrated by religious cults, their practices must be observed and made known to the general public through information centres. Religious leaders must also be willing to participate in ensuring that their practices do not cause harm to members and their families.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amor, A. 2004. Foreword by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief. In: T. Lindholm, W. Cole Durham, & B. Tahizib-Lie (eds.) Facilitating freedom of religion or belief: A desk book. (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff), pp. xv-xviii. [ Links ]

Barker, E. 2004. Why the cults? New religious movements and freedom of religion and belief. In: T. Lindholm, W. Cole Durham, & B. Tahizib-Lie (eds.) Facilitating freedom of religion or belief: A desk book. (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff), pp. 571-593. [ Links ]

Bowker, J. 1997. The Oxford dictionary of world religions. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Clark, R.W. 1997. New religious movements. [Online] Retrieved from: http://www.subgeniuscom/bigfist/FIST-2000-2/X0003_New_Religious_Movement.html [2010, 27 August]. [ Links ]

Cline, A. n.d. What is religion? [Online] Retrieved from: http://atheism.about.com/od/religiondefinition/a/definition.htm [2011, 12 May]. [ Links ]

Council of Europe Report. 1999. Illegal activities of sects. [Online] Retrieved from: http://www.rickross.com/reference/general/general70.html [2011, 3 May]. [ Links ]

Currie, I. & De Waal, J. 2005. The bill of rights handbook. Fifth edition. Landsdown: Juta. [ Links ]

Dictionary.com. n.d. Religion. [Online] Retrieved from: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/religion [2011, 13 May]. [ Links ]

Dürkheim, E. 1968. The elementary forms of the religious life. (Trans. by Joseph Ward Swain). London: George Allen & Unwin. (6th ed.). [ Links ]

Eliade, M. 1963. Patterns in comparative religion. New York: The World Publishing Company. [ Links ]

European Convention on Human Rights. n.d. European Convention on Human Rights. [Online] Retrieved from: http://hrcr.org/docs/Eur_Convention/euroconv3.html [2010, 11 August] [ Links ]

Hassan, S. 1988. Combating cult mind control. Rochester: Park Street Press. [ Links ]

Hexham, I. 1993. Concise dictionary of religion. Illinois: Intervarsity Press. [ Links ]

Hexham, I. & POEWE, K. 1997. New religions as global cultures. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Houtepen, A. 2000. From freedom of religion towards a really free religion. In: J.M.M. Naber (ed.). Freedom of religion: A precious human right. (Assen: Van Gorcum & Co.), pp. 1-17. [ Links ]

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. n.d. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. [Online] Retrieved from: http://www.2.ohchr.org/english/law/ccpr.htm [2010, 8 August]. [ Links ]

James, W. 1961. The variety of religious experience. New York: Collier Books. [ Links ]

Knights, s. 2007. Freedom of religion, minorities and the law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lerner, N. 2004. The nature and minimum standards of freedom of religion or belief. In: T. Lindholm, W. Cole Durham & B. Tahizib-Lie (eds). Facilitating freedom of religion or belief: A desk book. (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff), pp. 63-84. [ Links ]

Lifton, R.J. 1989. Thought reform and the psychology of totalism: A study of "brainwashing" in China. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Machovec, F.J. 1989. Cults and personality. Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. [ Links ]

Mather, G.A. & Nichols, L.A. 1993. A dictionary of cults, sects, religions and the occult. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Naber, J.M.M. 2000. Introduction. In: J.M.M. Naber, J.M.M. (ed.). Freedom of religion: A precious human right. (Assen: Van Gorcum & Co.), pp. 1-17. [ Links ]

Newsman, w. M. (ED.). 1972. The social meanings of religion. Chicago: Rand McNally College Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Random House Dictionary. 2010. Random House Dictionary. [Online] Retrieved from: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/religion [2010, 10 August]. [ Links ]

Robinson, M. 2004. Foreword by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. In: T. Lindholm, W. Cole Durham & B. Tahizib-Lie (eds). Facilitating freedom of religion or belief: A desk book. (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff), pp. xix-xx. [ Links ]

Singer, M.T. & Lalich, J. 1995. Cults in our midst. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

South Africa. 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 108 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

United Nations General Assembly Human Rights Council. 2006. Report of Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief Asma Jahangir. A/HRC/4/21, paras. 43-47, 26 December. [ Links ]

Vermeulen, B.P. 2000. Freedom of religion; past and present. In: J.M.M. Naber (ed.). Freedom of religion: A precious human right. (Assen: Van Gorcum & Co.), pp. 1-17. [ Links ]

Wikipedia. n.d. European Convention on Human Rights. [Online] Retrieved from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Convention_on_Human_Rights. [2010, 3 September] [ Links ]

Wikipedia. n.d. New religious movements. [Online] Retrieved from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_religious_movements [2010, 19 August]. [ Links ]

Wikipedia. n.d. Religion. [Online] Retrieved from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion [2010,17 August]. [ Links ]

Wikipedia. n.d. Sect. [Online] Retrieved from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sect [2010, 19 August]. [ Links ]

1 Religious cults are also included in the concept of new religious movements in the general definition.

2 Arrowsmith v. the United Kingdom App. No. 7050/75, 8 Eur. Comm'n H.R. Dec. E Rep. 123, 127 (1977).

3 Schuppin v. Unification Church, Civil No. 76-67 (D. Vt., filed April 8, 1976).

4 This refers to the case of Mr Paul Meintjies from Hertzogville in South Africa. After he died on 29 June 2004, his spiritual leader, a certain David Francis, sent an SMS to his relatives with the instruction: "Do not bury". The reason given for this was that God would raise the deceased from the dead. The remains of the deceased had to stay in the mortuary until this happened. After 54 days, the deceased's remains were finally laid to rest as a result of governmental intervention, since several attempts to raise him from the dead had failed, and the whole community of Hertzogville had been affected by this saga.