Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.31 n.1 Bloemfontein Jun. 2011

What's turning the wheel? The theological hub of Song of Songs

Fischer, S

Prof. S. Fischer, University of Vienna. Protestant Faculty of Theology. Research associate: Department Old Testament, University of the Free State, South Africa. E-mail: stefan.fischer@univie.ac.at

ABSTRACT

Different interpretations are evaluated for their contribution towards a better under-standing of the theology of Song of Songs. Chapter 4:16-5:1 is presented as the structural centre of Song of Songs. Linear, cyclic and concentric structures point to the centrality of this passage. It has a key-function for the theology of the book which is understood as creational theology because love recalls paradise. God is identified with the third voice, encouraging the lovers to enjoy love in all its fullness.

Keywords: Song of Songs; Structure; Paradise; Theology.

Trefwoorde: Hooglied; Struktuur; Paradys; Teologie.

1. CONSIDERATIONS ON METHODOLOGY AND THEOLOGY

The aim of this article is to contribute to the identification of the theological hub of Song of Songs. During an interpretive history of more than two thousand years various exegetical methods have been applied for purposes of identifying the theological message of Song of Songs. Yet, none has proven itself entirely convincing as the key for interpreting the book. Metaphorically speaking, the difficulties in determining the defining interpretative moment to the book may be expressed as follows: it is as if the "hub" is not at the centre of the "wheel" and hence the "wheel" bumps along instead of running smoothly in the interpretation of the book.

It should be conceded that, in dealing with Song of Songs, it may also seem curious as to why the question for the existence of a theology is even raised. Why should one look for theology in a book which does not so much as mention the word God directly, or, for that matter, one of the names of God? References to God have only been indirectly concluded, namely, in the conjuration of the gazelles and does of the field (2:7; 3:5) as an enigmatic allusion to the names of God (Murphy 1990:133) and also in a wisdom saying where a short form of the name Yahweh is used as a superlative (Winton Thomas 1953:216): "a mighty flame / the flame of Yah" (8:6).

Nevertheless, it is my contention that a text's theological base is not determined solely by the explicit presence of the name of God but also should the content of the text prove clearly theological or if the text is ascribed to an author who lays claim to a theological context. In this instance Solomon (1:1) is claimed as the author even though he is only loosely connected to the literary fiction of the two lovers. It should be conceded that Solomon is not necessarily known for, or associated with, explicit theological texts. Instead, he is known in the tradition as an archetype of love and a poet of songs and wisdom sayings. Yet, the reference to Solomon in the heading joins Song of Songs with Qoheleth and Proverbs. This might also have supported the inclusion of Song of Songs in the canon (Pope 1977:40-54). Furthermore, in all three books wisdom is associated with creation theology. Accordingly, one may therefore expect in Song of Songs utterances linked to creational theology.

Further, a text is deemed as theological in nature by the internal relation of the text to its context. In this respect Song of Songs is clearly part of the existing canon. The discourse of Song of Songs with other texts of the canon shapes the understanding of this book. Since texts develop their theological value through the interpretation within a canon, the canon in turn stabilizes the value of the text (Bekkenkamp 2000:58-61) and creates an intertextual network of interpretation.

Interpretation is established by an interpreter or an interpreting community, who unfold not only the text by its inherent criteria but apply also their opinion and methodological tradition to the text. Song of Songs has been scrutinized under such theological circumstances by the interpreting community. Ordinary people and theologians alike have therefore been looking for a theological hub or a hermeneutical key to resolve or understand the message of Song of Songs. The answers have been widespread, often shedding more light on the psyche of the interpreters and the Zeitgeist than on the text itself. My suggestion of paradisiacal love at the heart of the book may therefore also possibly be reflective of this. But it will be the responsibility of future generations of exegetes to decide this. Nevertheless, in order to truly reflect the entire spectrum of possibility, some preliminary alternatives to my own exposition of findings have first to be considered.

2. SEEKING FOR THE THEOLOGICAL HUB

2.1 Allegorical and typological reading

At the synod of Jamnia a discussion on the inclusion of Song of Songs in the canon took place. Rabbi Aqiva rebuked a profane, non-canonical usage of Song of Songs and cautioned that those who sing Song of Songs in a pub make it a secular song. These people will have no part in the world to come (Tosefta Sanhedrin 12:10). In a similar manner, bT Sanhedrin 101a states that whosoever sings a verse from Song of Songs in a pub brings about bad fortune. Instead, in early Judaism an allegorical interpretation was propagated (Salomonsen 1976:198), claiming that Song of Song deals with the loving relationship of God and his people.

This concept is applied to the people of Israel, thus transforming Song of Songs into a theological book expressing a spiritual relationship. This made it acceptable for the canon and, also, Rabbi Aqiva strongly emphasized that Song of Songs is the Holy of Holies of all writings: it defiles the hands if touched (bT Yadayim 3:5). The Targum Canticles read Song of Songs as a cryptic history or an eschatological allegory starting with the time of the Exodus and concluding with the Messianic age (Alexander 2003:13). Christian interpreters have extended allegorical interpretations to Christ as the bridegroom and the Church or the believer or even Mary, as the bride. Also anti-Semitic propaganda has been justified by an allegorical reading. Bernard de Clairvaux identified the mother of the bride with the synagogue and her brothers with Hannas, Kaiphas and Judas Iscariot, who took part in the crucifixion (Krichbaumer 1994:292). In a slightly different manner, Phillips (2003) bases his allegory on the dramatic interpretation of Ewald (1826), who distinguished two male characters, the king and the shepherd. Phillips (2003:18) identifies the bride with the church or the individual believers, the shepherd with Jesus Christ, who has won the heart of the believer or the church, and Solomon with the seducer, who leads the believers astray. In each interpretive instance the theological contribution is found in the allegorical transformation.

A typological reading is related to an allegorical one but does not deny a literal sense. Often both are left undifferentiated. Different objects in the text are considered images of a spiritual reality. The text prefigures a deeper truth.

Usually individual scenes are regarded as typos, which reflects salvation history or takes up an ecclesiological or Christological topic. Bernard de Clairvaux has held eighty-six sermons on Song of Songs and is an outstanding master of typology. For example, in sermon 70, he asks for the spiritual sense of the lover feeding among the lilies (2:16). In another interpretation the green bed of the lovers (1:16) is seen as the prosperity and growth of the church (von Bünau 1635:32) and the banquet hall (2:4) refers to the happy feast of the great supper (von Bünau 1635:40).

When the prophet Hosea uses "lily" (14:6) and "dove" (7:11; 11:11) as images of the people of Israel he might be relying on Song of Songs. Also, 4 Esdras 5:24-26 uses "vineyard", "lily", "dove" and "sheep" for the chosen people of Israel. The motifs, already used in Song of Songs, have become common metaphors (Myers 1974:193). They further a typological reading and contribute to a theological interpretation within a canonical framework.

In the first half of the 20th century, cultic interpretations became popular. The concept of the hieros gamos - which is not evident in Song of Songs - was nevertheless uncovered by relating Song of Songs to cults from Egypt (Isis and Osiris), Babylonia (Inanna and Dumuzzi) and Canaan. Cultic interpretations claim do uncover a hidden meaning. Thus they are likewise a development of the allegorical tradition and the dramatic interpretation (Brenner 1999:235).

2.2 Associative reading - relating phrases

In an individualistic, selective approach short quotations are utilized for the sake of an argument and work on an associative level. The text is understood as a mashal ( ), a wisdom teaching. Catchwords, sound, wordplay, as well as the reader's own cultural context give raise to the interpretation. This is also typical for some Talmudic interpretations. For example in the phrase "his banner over me is love" (2:4), the amount of the numbers of the letters for

), a wisdom teaching. Catchwords, sound, wordplay, as well as the reader's own cultural context give raise to the interpretation. This is also typical for some Talmudic interpretations. For example in the phrase "his banner over me is love" (2:4), the amount of the numbers of the letters for  ("his banner") is forty-nine. This number is used as an argument for a comparison with the love of the torah (bT Sanhedrin 22a, 66-69). In Orthodox Judaism the phrase, "your voice is sweet" (2:14) is utilized in the argument that a man is not allowed to listen to the voice of his spouse during her menstruation. Her voice is understood as a form of nakedness and it is thus forbidden to look at her (Rockmann 1998:72).

("his banner") is forty-nine. This number is used as an argument for a comparison with the love of the torah (bT Sanhedrin 22a, 66-69). In Orthodox Judaism the phrase, "your voice is sweet" (2:14) is utilized in the argument that a man is not allowed to listen to the voice of his spouse during her menstruation. Her voice is understood as a form of nakedness and it is thus forbidden to look at her (Rockmann 1998:72).

In an allegorical or typological interpretation the literal meaning is secondary, and a theological meaning would be far-fetched. Therefore, this would not answer the purpose of establishing the theological hub. The wheel would not turn smoothly.

2.3 Non theological reading

The profane usage of Song of Songs, which had been rejected by Rabbi Aqiva, has made it into 20th and 21st century biblical scholarship. Song of Songs is understood as an anthology. It is considered a mere collection of single poems or fragments thereof. They do not serve a theological purpose but merely praise the love between two lovers. The exchange of a declaration of love and faithfulness is thus considered the purpose of Song of Songs (Audet 1955:213). This reading assumes that there is no comprehensive cohesion and consequently also no coherence to be found in Song of Songs. This interpretation furthermore denies an overall structure as a frame of reference for the interpretation. Its focus is on love between two people and has no further or greater intention. It has merely a profane message.

3. THE IMPORTANCE OF STRUCTURE

3.1 Structure and meaning

3.1.1 Cohesion

When looking for the theological hub, content and structure have to be considered because both are transmitters of essential interpretive information. I propose an overall structure and rely on works of various scholars since Angénieux (1965). Different structures have been proposed and revised, most extensively by Elliot (1989). Structure is evident not only in the cohesion of textual elements, but also in the coherence of meaning - I have dealt with the question of structure extensively in a monograph on Song of Songs (Fischer 2010:39-87).

Cohesion explicitly expresses the linkage of sentences to a text. It deals with the manner in which a text is presented. It has long been noted that Song of Songs is constructed with a certain cohesion expressed by refrains and the repetition of keywords and phrases. The most obvious refrain is the conjuration: "Daughters of Jerusalem, by the gazelles and by the does of the field I charge you: Do not stir up or awaken love until it so desires" (2:7; 3:5; cf. 5:8; 8:4). Also the question: "Who is this coming up from the desert?" (3:6; 8:5; cf. 6:1) seems to resume an earlier event.

Phrases are represented by the call to get up (2:10.13), the praise of beauty (1.15, 4.1), the lovesickness of the woman (2:5; 5:8), her being in love (1:7; 3.1-4), the intimacy of tenderness (2:6; 8:3), browsing among the lilies (2:16.17; 4:5.6; 6:2.3) belonging (2:16; 6:3; 7:11) and privacy (2:7; 3:5), the praise of her uniqueness (4:7; 5.16; 6:9), and the call for (2:14; 8:13) or the sound of the voice of the beloved one (2:8; 5:2). Further metaphors are repeated (4:5 and 7:14; 4:3 and 6:7).

3.1.2 Coherence

Cohesion does not necessarily lead to coherence. Coherence demands more than the recurrence of keywords and phrases. It calls for continuity and causality. The different elements of a text are linked, for example, when a pronominal refers back to a figure of the text introduced earlier. Aspects of time, mode, voices and focalisation have also to be taken into account.

19th century dramatic interpretations already observed cohesion. Even if there has never been an agreement on the number of lovers wooing for the lady, some kind of a story was elaborated by focussing on some key texts.

If a story is to be extracted from Song of Songs, the prosaic and poetic parts must be evaluated. A prosaic text is more coherent than a poetic one. The syntagmatic dependency of the words is also greater in a prosaic text and it has fewer options for associations (De Sausurre 2001:152-153). Hence the prosaic parts are more important for the development of a story, but they are also less open to multiple interpretations. They have a stronger cohesion and are likely to be more coherent.

3.2 Structure as means of identifying a hub

Since meaning is expressed by cohesion and coherence, the clarification of the structure is functional for the understanding of a text and is a prerequisite to the theological message. In Song of Songs more than one structure can be identified. The complex and overlaying structures have often not been recovered so that Song of Songs was taken for an anthology, loosely joint by keywords or subjects.

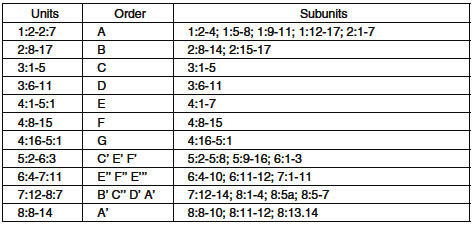

There are nevertheless arguments for a linear, a concentric and a cyclic structure (Fischer 2010:56-82). While a linear structure expresses progress, a concentric and a cyclic structure are both repetitious. A linear structure is typical for narratives which demand progress for the unfolding of the story. When structuring Song of Songs in consideration of the textual elements contributing to cohesion and the coherence of the content, the outline is as follows:

There is a linear order in the first half of the book. It ends in 5:1. The final function of 5:1 is supported by 4QCant which ends here. Most likely, this is not the accidental end of the fragment, but intended (Flint 2005:102). At the very least it reflects the possibility that the narration can be brought to a close.

5:2-8 recalls the scene of the woman seeking her lover in the dark of the night and meeting the watchmen (3:1-5), modifying it and developing a different story of seeking for the lover until the woman and the man are unified and the strength of the love is praised (8:5-7). An epilogue (8:8-14) closes the linear story of hide and seek.

In a concentric order, it may be observed that the second half of the book arranges the textual elements of the first half in a different order, repeating elements E and F more than once:

A B C D E F - G - C' E' F' E" F" E"' B' C" D' A'

All parts of the first sequence are taken up again in the second half. The larger blocks of the sequential order of the first half (B C D E F) are repeated in two blocks with internal repetitions (CEF - BCD) surrounded by a frame (A A'). The sequences become shorter, and have a summarizing and resultative effect. Only the centre, G (4:16-5:1), has no counterpart. It is the climax of the garden scene, F (4:8-15). The garden is the place where the lovers meet or try to meet each other (F' 6:1-3; F" 6:11-12).

Steinberg (2006:347-363) proposes the cyclical structure with five cycles of desire creating a repetitious movement: 1. She longs for him. 2. She sees him coming and praises his merits. 3. He praises her beauty and longs for her. 4. She invites him.

The third cycle closes with the paradise of love - he longs for her and she gives herself to him (4:16-5:1).

Each of the three structural devices point to 4.16-5:1 as the thematic and structural hub of Song of Songs. But what theological impact does this central passage possess? In order to solve this, the different voices in the text have to be identified.

3.3 Identification of different voices

In 4:16-5:1 three voices speak as follows:

Female voice: 16 Awake, north wind, and come, south wind! Blow on my garden, its fragrances shall flow. He shall come, my beloved to his garden, and eat its choice fruits.

Male voice: I am coming to my garden, my sister, my bride, I am gathering my myrrh with my spice, I am eating my honeycomb with my honey, I am drinking my wine with my milk.

Third voice: Eat, friends, drink, and be drunk, beloved!

I have translated the affix-conjugation of the male voice not as a present perfect but as a present progressive tense because this act of speech is not a report but a dramatic conversation between three voices. The female voice invites the man. He answers the invitation and expresses his desire for her. When speaking, the sexual unification of the two is either just about to take place or their speech accompanies it (Wagner 1997:125). The uninterrupted intimacy of the male and the female figures is at the centre of Song of Songs and this is accompanied by a third voice. The switch-over is indicated by the change from first person affix conjugation to the imperative masculine plural. The identification of the third voice is a crux interpretum. The identification of the addressee might contribute to its solution.

The voice is not addressing the man's companions, who remain obscure and appear only in the framework (1:7; 8:13) as  but never as

but never as  Instead, this voice addresses the lovers and calls them "friends" and "beloved". In Song of Songs, and only there, the feminine form

Instead, this voice addresses the lovers and calls them "friends" and "beloved". In Song of Songs, and only there, the feminine form  of the term

of the term  appears nine times. If the man and the woman are addressed together, it is common that the masculine plural form is used. Concerning the second term

appears nine times. If the man and the woman are addressed together, it is common that the masculine plural form is used. Concerning the second term  , the LXX and the Old Latin Version are misleading, translating

, the LXX and the Old Latin Version are misleading, translating  as

as  δ

δ λΦο

λΦο , respectively fraters mei.

, respectively fraters mei.  points to the lovers as well. Instead, in Song of Songs,

points to the lovers as well. Instead, in Song of Songs,  is always used by the male or female to address the other as beloved.

is always used by the male or female to address the other as beloved.

If the man and the woman are the addressed, it follows that they cannot at the same time be the speakers. Fox (1985:139) suggests that the daughters of Jerusalem are speaking. Although in other intimate situations the daughters of Jerusalem are present and even adjured, but they are never called friends. Their function is to support the lovers (2:7; 3:5; 5:8) by ensuring their intimacy.

Also, the identification of this voice with a chorus (Garrett 2004:201; Hess 2005:156) is based on the assumption of an unknown group. Hess points to similar imperatives but does not take into account that in the closest parallels the assumed vineyard-workers (2:15) and daughters of Jerusalem (2:5) have a passive function: they are addressed but not addressing. The identification as a chorus would be plausible on the supposition that Song of Songs is a drama.

It should be emphasized that this third voice cannot be assigned to another figure appearing within Song of Songs. Gerleman (1965:162) suggests that the poet himself is speaking. Thus he adds another literal level, because the voice of the poet is external to the story. His suggestion can be further refined: this is the voice of the narrator who interprets the scene. As such, he is an omniscient interpreter.

4. THEOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS

In a theological interpretation the omniscient voice of 5.1b is the voice of God. God is present to the intimacy of the garden. At the centre of Song of Songs, it is He who supports and shelters the lovers. This claim can only be made if the paradisiacal situation of the entire scene is appreciated. Several parallels between this garden and the Garden of Eden have been claimed: the plants, the fruits, the spices, the rivers and the flowing water. Landy (1983:189-265), for example, presents a detailed analysis. He comes to the conclusion that this garden is in close correspondence to the imagery of the Garden of Eden. The garden is,

essentially private ... man's first organisation of the world ... a contained world ... cultivated aesthetically ... a metaphor for poetry ... secluded and universal, primordial and inaccessible (Landy 1983:190).

Since the garden is a metaphor for the woman, the beauty of the garden corresponds to her beauty. The Garden of Eden is locked and mankind has been expelled (Gen 3:22-24) but metaphorically, in Song of Songs, the woman herself is a locked garden (4:12). She does not restrain herself from her lover but opens up to him (4:16). The union of the two lovers takes place in the garden. She is a fruitful orchard (4:13.14), like a paradise or the Greek Elysium. She is a fountain, a well of living waters, a stream, and she alone allows him to drink (4:15). He experiences the intimacy of two lovers, which is also the ideal within the wisdom tradition (Prov 5:15-19). Her fragrance and voluptuous appearance give a sensual pleasure like the choicest food and drink. The intimacy of lovemaking is the place of recreation.

This passage can be read as if the lovers are placed into paradise and resemble Adam and Eve as prototypes of man and woman. They are the ideal lovers. Barbiero suggests that love is the way back to paradise (Barbiero 2002:189). The immediacy of the third voice recalls the voice of God in the Garden of Eden. When taking into account that God is implicated in this scene and summons the lovers to become intoxicated with lovemaking, love becomes the remedy for regaining paradise. It is these two who meet for lovemaking. In this manner the paradisiacal ideal of one man and one woman is praised.

In an allegorical interpretation, Gregory of Nyssa (1984:43) identifies another garden with paradise, namely, the vineyard (1:5). It is plausible that the vineyard as well as this garden might resemble the woman, but the situation is nevertheless different as she did not keep her vineyard as the first men did not keep paradise. In contradistinction to this, no lapse has taken place yet. It is the pre-fall world which is recalled and paradise that is regained in love. This timeless situation, without age and aging of the lovers, stresses the paradisiacal condition.

The imperatives of the third voice affirm man and woman to continue and to intensify their love. The two lovers unite as the primordial couple was one (Genesis 2.18.20). They are called to eat, drink and get drunk. Eating and drinking here point to the natural enjoyment but the call to become drunk expresses that love intoxicates. People who are drunk are busy with themselves. They have no other business to attend to. If God therefore calls the lovers to focus all attention on themselves, He acts to safeguard them. If this was originally part of a drinking song (Loretz 1971:32) it would therefore be even more offensive to put it into the mouth of God. This is the climax of love.

The external voice is also raised in 8:6b-7, the final words before the epilogue in a linear reading of the text. These words can also not be assigned to one of the figures in the text and sound like the comment of the interpreter. They are shaped as a wisdom-saying and might even be a quotation of one:

Love is strong as death; jealousy is fierce as the grave. Its flashes are flashes of fire, the very flame of Yah. Many waters cannot quench love, neither can floods drown it. If a man offered for love all the wealth of his house, he would be utterly despised.

Verses 4:16 and 8:6b-7 are prominent on a structural level and have distinct theological statements to make, the latter emphasizing love as the highest gift of Yahweh. This is in form and content singular in Song of Songs but not uncommon to a proverbial wisdom saying.

Thus we have two structural focuses with theological significance, namely, a wisdom teaching on the strength of love as a gift of Yahweh (8:6b.7) and an intimate scene of lovers (4:16-5:1) guaranteed by God. These two passages correlate by their structural position and by the theme of love but contrast in scene, the one expressing love as secure intimacy within a natural setting and the other as being endangered by the natural element of the waters. Thus they extend the tension of paradisiacal love and worldly endangerment. It should be emphasized that marriage, as a moral presumption, is no theme in this setup, but rather the natural love of desire which is neither open to bribes nor irresponsible: those whose hearts are sealed with love will resist the endangerment of circumstances. In this paradise love is present and man is reminded of his origin, as already Herder (1778:126) stated, "Als Gott den Menschen im Paradiese schuf, ward Liebe sein zweites Paradies."1

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, P.S. 2003. The Targum of Canticles. Translated, with a critical introduction apparatus, and notes. London: T & T Clark. (The Aramaic Bible 17A). [ Links ]

Angénieux, J. 1965. Structure du Cantique des Cantiques. ETL 41:96-142. [ Links ]

Audet, J.P. 1955 Le sens du Cantique des Cantiques. RB 62:197-221. [ Links ]

Barbiero, G. 2002. "Leg mich wie ein Siegel auf dein Herz - Fliehe mein Geliebter": Die Spannung in der Liebesbeziehung nach dem Epilog des Hohenliedes. In: G. Barbiero (Hrsg.). Studien zu alttestamentlichen Texten. (Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk), pp.185-198(SBAB 34). [ Links ]

Bekkenkamp, J. 2000. Into another scene of choices: the theological value of the Song of Songs. In: A. Brenner (Ed.) The Song of Songs. 55-89. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. (A feminist companion to the Song of Songs. Second Series). [ Links ]

Bernard De Clairvaux 2007. Sermons sur le cantique. Paris: Les Editions du Cerf. (Sources Chrétiennes 511). [ Links ]

Brenner, A. 1999. Das Hohelied. Polyphonie der Liebe. In: L. Schottroff & M-T Wacker (Hrsg.) Kompendium Feministische Bibelauslegung. 2nd Edition. 233-246. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. [ Links ]

De Sausurre, F. 2001. Grundfragen der allgemeinen Sprachwissenschaft. 3. Auflage. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Elliott, M.T. 1989. The literary unity of the Canticle. New York: Peter Lang. (EHS.T. 23/371). [ Links ]

Ewald, G.H.A. 1826. Das Hohelied Salomo's übersetzt mit Einleitung, Anmerkungen und einem Anhang über den Prediger. Göttingen: Rudolph Deuerlich. [ Links ]

Fischer, S. 2010. Das Hohelied Salomos zwischen Poesie und Erzählung: Erzähltextanalyse eines poetischen Textes. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. (FAT 72). [ Links ]

Flint, P.W. 2005. The book of Canticles (Song of Songs) in the Dead Sea Scrolls. In: A. C. Hagedorn (Hrsg.). Perspectives on the Song of Songs. (Berlin: de Gruyter), pp.96-204 (BZAW 346). [ Links ]

Fox, M.V. 1985. The Song of Songs and the ancient Egyptian love songs. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. [ Links ]

Garrett, D. 2004. Song of Songs. Nashville: Thomas Nelson. (WBC 23B). [ Links ]

Gerleman, G. 1965. Ruth. Das Hohelied. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener. (BKAT XVIII). [ Links ]

Gregory of Nyssa 1984. Der versiegelte Quell: Auslegung des Hohen Liedes. In Kürzung übertragen und eingeleitet von Hans Urs von Balthasar. Einsiedeln: Johannes. (Cme 23). [ Links ]

Herder, J.G. 1778. Lieder der Liebe. Die ältesten und schönsten aus dem Morgenlande. Nebst vierundvierzig alten Minneliedern. Leipzig: Weygandsche Buchhandlung. [ Links ]

Hess, R.S. 2005. Song of Songs. Grand Rapids: Baker Academics. (Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms). [ Links ]

Krichbaumer, M. 1994. Die Stellung von Sermo super Cantica Canticorum 14 im Gesamtwerk Bernhards von Clairvaux. MThZ 45/3:289-300. [ Links ]

Landy, F. 1983. Paradoxes of Paradise: Identity and Difference in the Song of Songs. Sheffield: Almond Press (BiLiSe 7). [ Links ]

Loretz, O. 1971. Das althebräische Liebeslied: Untersuchungen zur Stichometrie und Redaktionsgeschichte des Hohenliedes und des 45. Psalms. Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener (AOAT 12,1). [ Links ]

Murphy, R.E. 1990. The Song of songs: a commentary on the Book of Canticles or the Song of Songs. Minneapolis: Fortress (Hermeneia). [ Links ]

Myers, J.M. 1974. I and II Esdras. Garden City / New York: Doubleday & Company. (AncB 42). [ Links ]

Phillips, J. 2003. Exploring the love song of Solomon. An expository commentary. Grand Rapids: Kregel. (John Phillips Commentary Series). [ Links ]

Pope, M.H. 1977. Song of Songs. Garden City / New York: Doubleday & Company. (AncB 7). [ Links ]

Rockmann, H. 1998. Sexualverhalten ultraorthodoxer Juden und Jüdinnen. In: S.-H. Lee-Linke (ed.). Das Hohelied der Liebe: weibliche Sexualität in den Weltreligionen. (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener), pp.65-79. [ Links ]

Salomonsen, B. 1976. Die Tosefta. Seder Nezikin. Sanhedrin-Makkot. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. (RT 4,3). [ Links ]

Steinberg, J. 2006. Die Ketuvim - ihr Aufbau und ihre Botschaft. Hamburg: Philo (BBB 152). [ Links ]

Von Bünau, C. 1635. Kurtze und einfältige Betrachtungen und Auslegungen über das Hohe Lied Salomonis. Basel: Johann Jacob Genath. [ Links ]

Wagner, A. 1997. Sprechakte und Sprechaktanalyse im Alten Testament. Untersuchungen im biblischen Hebräisch an der Nahtstelle zwischen Handlungsebene und Grammatik. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. (BZAW 253). [ Links ]

Winton Thomas, D. 1953. A Consideration of Some Unusual Ways of Expressing the Superlative in Hebrew. VT 3/3:209-224. [ Links ]

This article is base on a lecture held at the UFS on March 6, 2009.

1 "When God created mankind in paradise, love became his second paradise."