Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Theologica

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.30 no.2 Bloemfontein dic. 2010

The racial discourse and the Dutch reformed church: looking through a descriptive-empirical lens ... towards a normative task1

W. J. Schoeman

Prof. W.J. Schoeman, Department Practical Theology, University of the Free State. E-mail: schoemanw@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The discourse between the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) and race is a difficult and intense one. The aim of this article is to give a descriptive-empirical description of the relationship between the DRC and race by using the Church Mirror surveys. An altered social distance scale is used to measure church acceptance. In the discourse on race, acceptance and unity in the DRC with regard to racial prejudice and attitudes towards the "other" group have a stronger voice than theological or religious arguments. As a normative task in this discourse, at least two aspects can be pointed out: developing a framework for forgiveness and a confession on racism.

Keywords: Racism, Social distance, Church acceptance, Church unity, Church Mirror surveys, Dutch Reformed

Trefwoorde: Rassisme, Sosiale afstand, Kerklike aanvaarding, Kerk eenheid, Kerkspieël opnames, Church NG Kerk.

The Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) distanced itself from racism in the middle eighties, and in the nineties, South Africa became officially a non-racial democracy. However, the conclusion cannot be made that race and racial differences do not play a major role in South African society today. The racial "card" is part of the current debate, and the church is part of the discussion and probably part of the problem. In November 2009, the Weekend Argus reported, "Jansen blames racism on NGK". Jansen argued that the church, as one of the agencies of socialisation in society, helped entrench racism in South Africa. "The most dangerous for me is the NG Kerk." The role of the home, churches, schools and the university cannot be overlooked in the damage racism has done to society. He questions if the church shares the broader values of non-racialism (Jansen 2009a: 1). This is but one of many critical voices asking the question about the relationship between racism and the DRC.

The relationship between the DRC and race is one of division. Race and dealing with racial differences are an integral part of the history of the DRC. Today, the DRC is still predominantly a "white" church and at odds with her family members that are "non-white". The DRC is being held responsible partially for racial problems in South Africa.

In doing Practical Theology, it is important to answer the question: What is going on? Osmer (2008: 4) describes this as one of the tasks of Practical Theology to gather information that helps discern patterns and dynamics in certain situations and contexts (the descriptive-empirical task of Practical Theology). The aim of this article is to give a descriptive-empirical account of the relationship between the DRC and race. In the end, a question will also be asked about the normative task of Practical Theology in this regard.

1. A DESCRIPTION OF THE CONCEPT "RACE"

In the beginning, it is necessary to give a brief description of the concept "race". Race is more than the colour of you skin, although it is more than 80% of a person that you see (see Snyman 2008: 397). Race is not only a scientific or biological category, but it is also a political and social construct. Race is not an objective, stable, homogenous category but is produced and animated by changing, complicated and uneven interactions between social processes and individual experience (Gunaratnam 2003: 8). On the one hand, race is a source of violence and hatred, and sometimes it extends our humanity and our being in the world, but it

forms the matter from which we and the world are socially and existentially formed, so race still matters today in ways that are difficult to overstate (Alexander & Knowles 2005: 16).

Race is a dynamic concept and not easily defined.

It is important to note that race as a concept is constructed socially. Social discourses and social power relations play an important part in defining and describing race as a concept. Race is much more than just a biological category or biological differences. It must be understood in a social context (see Gunaratnam 2003: 4-14). Race cannot be understood without the social context in which it is used, in this case South African society, especially the DRC with a predominantly "white" membership and an "apartheid" history. Therefore, the description and use of race in this article is contextual and subjective.

Thus, race cannot be described in terms of only a few categories. Research on race is mostly a subjective process, and there is a need to work through "the tense entanglements, interdependencies and junctions between categories and social relations" (Gunaratnam 2003: 22). The relationship between race and religion is also a complex relationship. This empirical description is thus limited by the difficulty in the conceptualisation of race and its social construction.

This article asks the question: Are racial issues and the accepting of members of a different racial background still part of the discourses in the DRC? How did the new non-racial South Africa influence racial differences in the DRC? How does the DRC deal with these racial differences? It is necessary to give a short historical background description of the racial discourse in the DRC before these research questions can be considered through an empirical lens.

2. THE RACIAL DISCOURSE IN THE DRC - A FEW BACKGROUND REMARKS

The history of the DRC began with the establishment of a settlement at the Cape of Good Hope in Southern Africa in 1652. For the first 150 years, the "white" settlers and "black" converts belonged tot the same church community. Separate congregations for black members started in 1863 and a synod for the "coloured" members was formed in 1881 (Dutch Reformed Mission Church in South Africa). The Dutch Reformed Mission Church in South Africa "stands as an historical symbol of institutionalized racial segregation" in the DRC (De Gruchy 2010: 54). After 1881, the planting of indigenous churches along racial lines became a fixed pattern, for instance the Dutch Reformed Church in Africa for Blacks and the Reformed Church in Africa for Indians (see Ned Geref Kerk 1986: 4-5). These churches form part of the family of Dutch reformed churches. Historically, from 1881 until 1990, the DRC was predominantly a church for "white" members only.

Since the 1960s, the pressure was on the DRC to distance itself from racism and apartheid. In this regard, refer to the Cotesloe meeting, the SACC and the role of individuals such as Beyers Naude. The voice and struggle against apartheid and racism were developed in South Africa by the churches who were members of the South African Council of Churches and the Roman Catholic Church, as well as other faiths such as Judaism and Islam (see Dolamo 2005: 330 and Nelson 2002: 68).

The General Synod of the DRC of 1986 condemned racism as sinful, and in 1990 it repudiated apartheid as a sin. The DRC technically became an open church. What are church members' and the leadership's views on this? Are DRC members willing to accept racially different persons as members and are they willing to cross the racial divide and become one united church again? It is possible that there is a gap between the official policy and the attitude of members and the leadership (see Pieterse, Scheepers & Van der Ven 1991: 69-71).

The 1990s saw radical changes in the South African society. The political situation changed radically after 2 February 1990 with the unbanning of the ANC and other political parties and the subsequent release of Nelson Mandela. With the abolition of most racially based laws in 1991, racism in South Africa was deinstitutionalised officially (Hamilton et al. 2001: 50). This was followed by the first non-racially elected democratic government in 1994. The consequence of these changes was not that South Africa became a nonracial society, but South Africa is still very much, if not legally so, a racialised society (Stevens, Franchi & Swart 2006: 9). Racial issues remain part of the public discourse, and the church is part of this discourse. The question remains: How did these changes influence racial attitudes in the DRC? An empirical lens will now focus on this question.

3. THE CHURCH MIRROR SURVEYS

The DRC started in 1981 with a national church census and survey called "Church Mirror". It is done every four years among the congregations, church leaders and ministers of the DRC. The data and findings used in this article are from these surveys.2

4. DESCRIBING CHURCH ACCEPTANCE

The concept of "church acceptance" was developed in the Church Mirror surveys to measure the degree of acceptance or approval in the DRC towards members of the DRC family. Social acceptance was used as a theoretical framework for developing and operationalising the concept of church acceptance.

Social acceptance as a concept refers to the favourable reception or approval of a person or group of persons. Social acceptance can be described by measuring the social distance between individuals or groups. Social distance may be defined as

the degree of closeness or intimacy of association into which an individual, individuals, group or groups are willing to enter or to which they are willing to admit, the members of their own group or the members of other group or groups (Lever, 1978: 105).

According to Bichi (2008: 489),

social distance is the lack of availability and relational openness - of variable intensity - of a subject in regard to others perceived and acknowledged as different on the basis of their inclusion in a social category.

In 1925, E.S. Bogardus developed a social distance scale to measure the closeness of contact the respondents may or may not want with a specific group (Babbie & Mouton 2001: 151; Bichi, 2008: 488). This scale and adapted scales are still used to measure social distance, for example in education, the acceptance of the mentally ill, ethnic groups, disabled people, people with specific diseases, occupational groups, etc. (see Wark & Galiher 2007: 392 and Ponton & Gorsuch 1988: 270).

The concept of "social distance" and the social distance scale were used in the Church Mirror surveys as a scale to measure church acceptance. The generalised variety of the scale makes it possible to use it in such a way, and the scale then uses "five to seven statements that express progressively more or less intimacy toward the group considered" (Wark & Galiher 2007: 392). Therefore, the question is asked: To what extent are leaders and ministers in the DRC willing to accept members of the DRC family? The concept of social acceptance is altered to consider church acceptance. In other words, are members of a specific church willing to accept members of an "other" church in their "own" church, and to what extent?

This research question was operationalised by using an altered social distance scale, referring to church acceptance instead of social acceptance. The following was put to the respondents:

In connection with members of the DRC family that are not from your own racial group, please indicate your reaction on each of the following statements:

As a first reaction, I am prepared to

• support a ministry for them

• attend a conference with them

• attend a funeral or marriage sermon with them

• attend a worship service with them

• celebrate Holy Communion together

• accept them as members of my congregation

These questions were first put to the church leaders in the survey of 1989 and to ministers in 1996. The data used for 2005 come from three DRC synods in the northern part of South Africa, and the rest comes from the whole of the DRC.

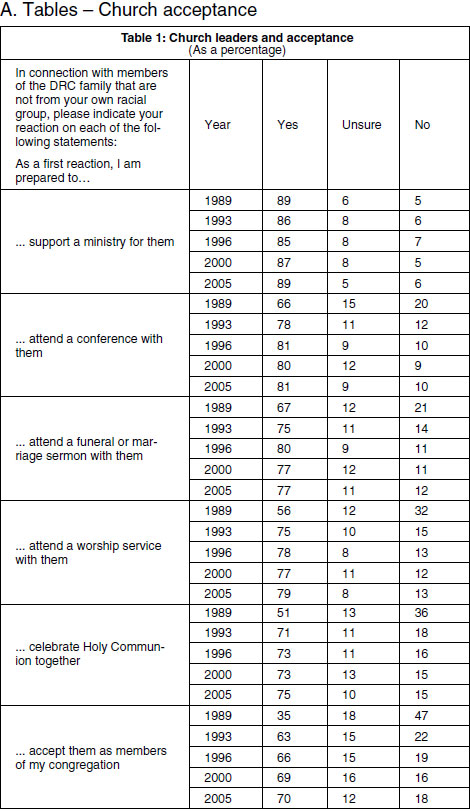

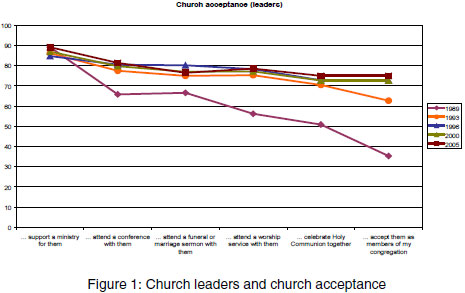

4.1 Church leaders and church acceptance (see Table 1 and Figure1)

The responses on the church acceptance scale indicate that it becomes more difficult as the other group becomes closer: Church leaders do not have any problem in supporting a ministry, attending a conference, funeral or marriage sermon with members of the DRC family. A majority is also in favour of attending a worship service or celebrating Holy Communion, but becoming a member of the congregation is more difficult.

Two remarks can be made when considering Figure 1:

• Church acceptance follows a pattern more or less similar to that of a social distance. Bringing members of the out-group nearer is more difficult, and supporting a ministry for them is much more acceptable than accepting them as members of one's congregation.

• There is a distinct difference between the pattern for 1989 and the rest of the responses. The out-group becomes much more acceptable after the 1989 survey. The question is what happened between 1989 and 1993? The most probable explanation is the political and social change that had taken place in South Africa led to a change in attitude and acceptance.

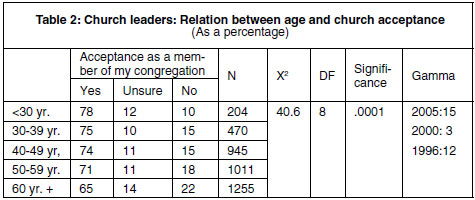

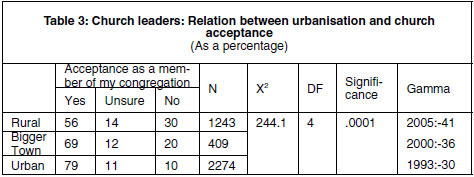

How does age as an independent variable influence church acceptance as a dependant variable? younger church leaders are more open in accepting members of the DRC family than older members (Table 2). Age explains between 3% and 15% of the variance in the responses. Church leaders from congregations in urban areas are more positive in accepting members of the DRC family than leaders from the rural congregations (Table 3). The gamma value varies between 30% and 41%. Urbanisation explains more of the variance than age. Leaders in rural congregations are more conservative and reluctant in accepting members from the out-group.

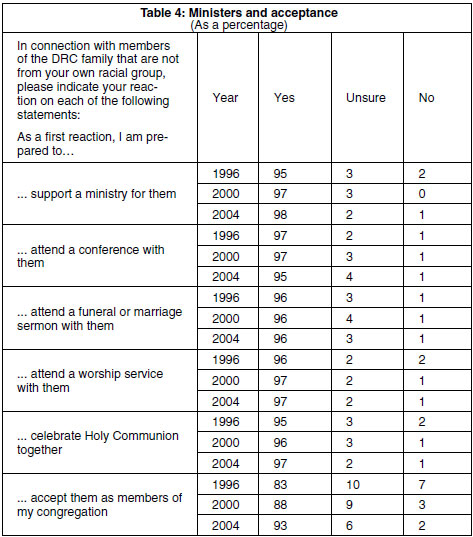

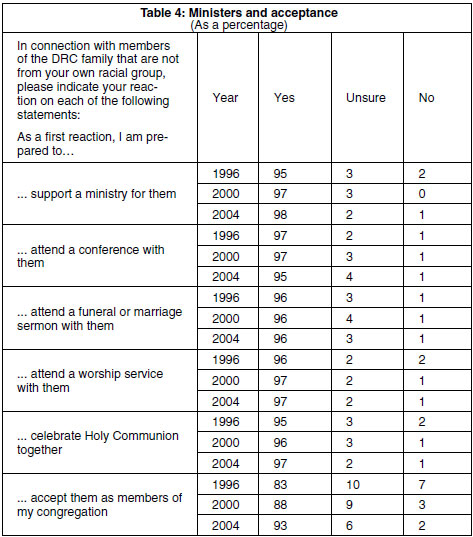

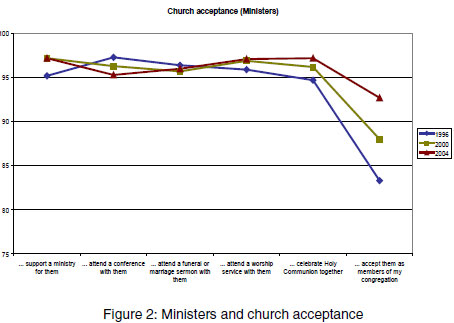

4.2 Ministers and church acceptance (Table 4 and Figure 2)

In 1996, ministers were asked for the first time about their acceptance of members of the DRC family, using the church acceptance scale. A great majority responded positively to the six statements. Their responses were more positive than those of the church leaders, which could be expected. Over time, the ministers had also become more positive about acceptance of members of the DRC family as members of "my congregation." This attitude increased from 83% in 1996 to 93% in 2004.

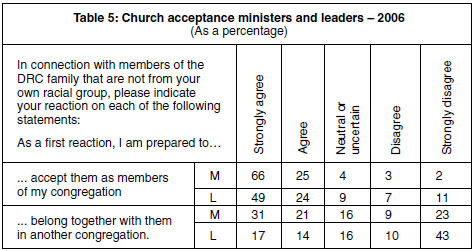

4.3 Members of my or another congregation?

Is there a difference between accepting members in "my congregation" and belonging together in a new or another congregation? In "my congregation", I am making the rules, but in another congregation, "we" are going to negotiate the conditions and rules together. This question was asked to the church leaders and ministers in the 2006 survey (Table 5). Both ministers and leaders are more willing to accept them in "my congregation" than belonging with them in another congregation. This response probably indicates something about power relations in and between congregations: In "my" congregation, it is "my" decision.

5. THE QUESTION OF CHURCH UNIFICATION

The discourse on the unification of the DRC and its family is not only a theological debate, but also one of race and power. It is also a question of accepting "other" persons. The General Synod of the DRC has accepted in principle that unification between the different churches is important. The question is whether the ministers and church leaders share this attitude and are willing to unite. Questions regarding this issue were asked from the 1996 survey onwards.

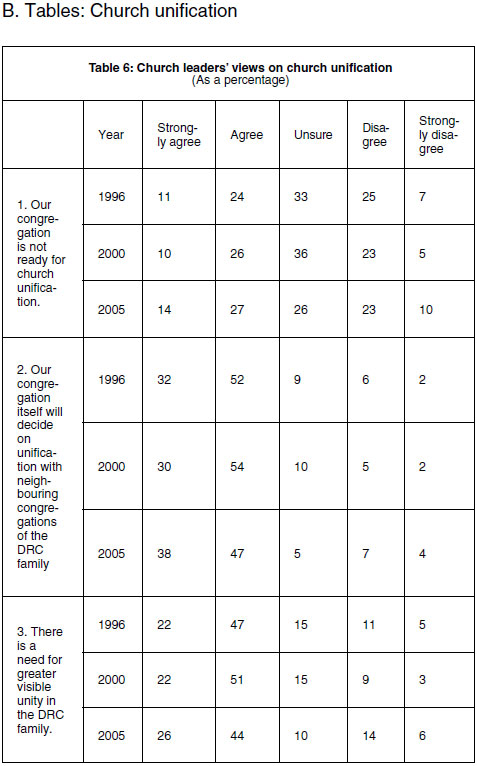

5.1 The attitude of church leaders regarding church unification (Table 6)

Are the leaders and congregations ready for unification with the congregations of the DRC family? Most church leaders agree that visible unity is important (3), but they are unsure whether their congregations are ready for unification (1). They feel strong about deciding independently about unification with neighbouring congregations (2); the power to decide must be in their own hands. This is a theory and practice problem, saying "yes" is one thing, but doing is another.

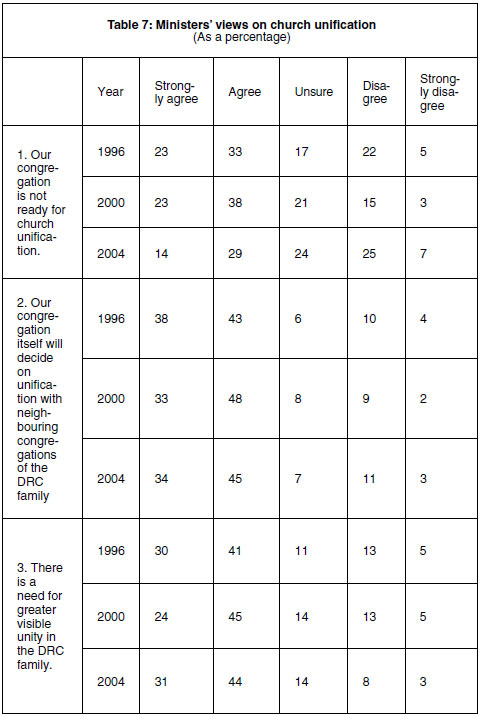

5.2 The attitude of ministers regarding church unification (Table 7)

There is not a big difference between the attitudes of ministers and church leaders regarding church unification. They are positive about visible unity (3), feel strongly about deciding independently about unification (2) and are of the opinion that their congregations are not ready for unification.

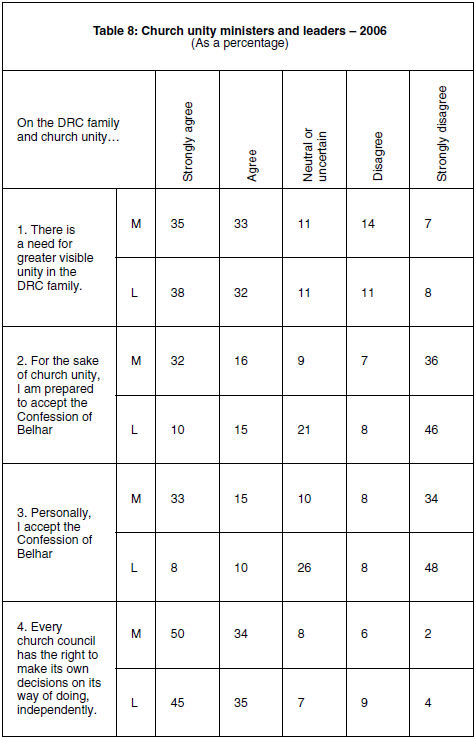

5.3 Church unity 2006

In August 2006, the same questions were put in separate questionnaires to church leaders and ministers (see Table 8). The following remarks can be made:

• A majority of ministers and church leaders agree that there is a need for greater visible unity in the DRC family (1).

• More ministers than church leaders are willing to accept the Confession of Belhar3 for the sake of church unity. A majority of church leaders are not willing to accept the Confession of Belhar for the sake of church unity (2).

• Being willing to accept the Confession of Belhar as a personal confession (3): Ministers are more positive than church leaders. A majority of church leaders are not willing to accept this confession as a personal confession.

• Ministers and church leaders feel strongly about making their own independent decisions on unity.

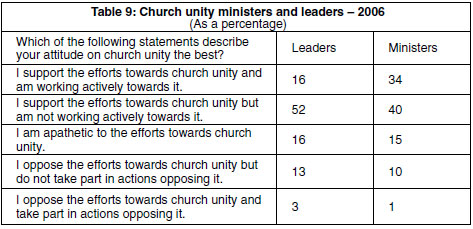

Is there an active drive towards church unity in the DRC? Only a third of the ministers are working actively towards the goal of church unity (Table 9). The rest of ministers and leaders say "yes" and do nothing or stand apathetic towards the process. It seems that they are strengthening the status quo.

6. RACISM AS A SOCIAL PROBLEM

Underlying the discussion of the responses on church acceptance and church unity is the whole question of race and racism. Prejudice and discrimination towards other group(s) are part of a question about racism. Racism is related to an ideology, but also to the level of everyday social practices "that construct and reflect hierarchical notions and representations of the Self and the Other" (Stevens et al. 2006: 11). Racism is deeply rooted in South African society. In the context of the discussion in this article, the question is whether congregations pay attention to the social problem of racism. Is racism on the agendas of congregations?

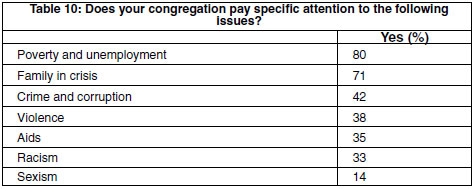

The South African Christian Leadership Assembly (SACLA) held a national conference in 2003. At the conference, they identified seven giants that are challenges to the South African community, namely HIV and Aids, violence, racism, poverty and unemployment, sexism, family in crisis, crime and corruption (Bisschoff 2008: 10). In the 2006 survey, ministers were asked to indicate whether their congregations were paying specific attention to these seven giants (Table 10). Congregations paid the most attention to poverty and unemployment (80%) and families in crisis (71%). Sexism (14%) and racism (33%) received the least attention in congregations. The last response is a clear indication that congregations do not consider racism as a problem serious enough to be high on their agenda.

7. THE RACIAL DISCOURSE - CONCLUDING

REMARKS What do we see through the empirical and descriptive lens of the Church Mirror surveys?

On church acceptance: In a certain sense, there is not a great difference between church acceptance and the results of other studies on social acceptance and social distance (Lever 1978:102-133; Coetzee s.a.: 7998; Pieterse et al. 1991: 64-85; Smith, Bowman & Hsu 2007: 436-443). Church leaders and ministers of the DRC accept members of their "own" group more easily than members of the "other" group. As is the case with social acceptance, church acceptance is much more a social issue than a religious issue.

On church unity: Against the background of church acceptance, the lack of enthusiasm for church unity from the side of the DRC leadership is explainable. Why do you want to unite with persons that are not, in your context, socially acceptable? The church policy may sound the right wording, but "my" group is going to determine the acceptance of the other group. This makes the church unity discourse much more a case of social acceptance than a debate about theology.

On racism: In the debate on church unity in the DRC family, racial prejudice may have the last word, and not theological or religious arguments. This may also explain why racism is not a burning issue in congregations. Congregations do not have a need to discuss and handle racial issues and differences.

The deeply rooted racial and social differences in the DRC and with its family cannot be ignored. The challenge is to deal with these differences in a constructive way when crossing the racial border. The criticism still remains that the church is the

only space in which the Afrikaners can be left alone to be white and Afrikaans without interference; they remain the only arena that is, in many cases, still all-white and all-Afrikaans in the new South Africa (Jansen 2009b: 35).

Looking through the empirical lens, the racial undertones of this situation is evident. A way of combating racism is through the changing of attitudes through education and experience of interacting with members of other groups in an atmosphere of equality and trust (Hamilton 2001: 24). There is a definite need to cross racial borders, because "keeping people within racial categories [denies] a reality of people moving across racial borders to form multiple social belongings" (Snyman 2008: 403).The church ought to be a "social network" of new belonging.

A further task of Practical Theology, as Osmer (2008: 4) points out, is to ask what ought to be going on (the normative task of Practical Theology). Among others, at least two aspects can be pointed out in looking for the normative task in this regard: developing a framework for forgiveness and a confession on racism.

A way of performing this normative task is to develop an ethics of forgiveness (Vorster 2009: 366). The racial discourse is about misunderstanding, not accepting one another and in most cases broken and painful relationships. A normative way of healing and reconciliation would be a choice for forgiveness. Beacons in developing ethics of forgiveness are human dignity, human depravity, human redemption and the new beginning brought about by the reality of the kingdom of God (Vorster 2009: 370-380). Therefore, racial differences can be handled within the framework of ethics of forgiveness. Therefore, Christians should not only be active agents in the restoration of distorted relations, but also whistle blowers whenever and wherever the table is set for new social injustices that may emerge. Thus, forgiveness requires an ethos of "this may not happen again" (Vorster 2009: 378-379). Forgiveness creates a space for acceptance, a way of healing the pain of racism.

Secondly, as a normative task, the Confession of Belhar may help in formulating a confession on racism. The third article of the Confession of Belhar states, "We believe that God has entrusted to his Church the message of reconciliation in and through Jesus Christ; that the Church is called to be the salt of the earth and the light of the world that the Church is called blessed because it is a peacemaker, that the Church is witness both by word and by deed to the new heaven and the new earth in which righteousness dwells." In view of article three, the confession makes the following conclusion on race: "Therefore, we reject any doctrine which, in such a situation sanctions in the name of the gospel or of the will of God the forced separation of people on the grounds of race and colour and thereby in advance obstructs and weakens the ministry and experience of reconciliation in Christ."

Are there real and normal differences to explain this racial discourse? This article started with the criticism of Jansen on the DRC. Maybe it is appropriate to end with a dialogue to illustrate that the racial discourse needs to change (Jansen 2009b: 136-137). The discussion is between Jansen and a student on the reasons why students are segregated by race.

Student: But our cultures are different.

Professor: But how does your culture differ from mine?

Student: We speak Afrikaans.

Professor: But I am speaking to you in Afrikaans right now.

Student: But we are Dutch Reformed church goers.

Professor: My mother was actually Dutch Reformed.

Student: But we barbeque.

Professor: You are talking to a meat eater.

The descriptive-empirical lens has shown and highlighted the racial and social framework of the discourse on church acceptance, unity and racism in the DRC. From a normative viewpoint, the DRC made certain statements on its position regarding issues on unity and racism, but the discourse on race in the church has not changed much. The normative task may be in need of an ethics of forgiveness and a confession on racism. The strategic challenge for DRC is to do something to change this racial discourse.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander C. & Knowles C. 2005. Making race matter bodies, space and identity. Palgrave MacMillan: New york. [ Links ]

Babbie E. & Mouton J. 2001. The practice of social research. Oxford University Press: Oxford. South African edition. [ Links ]

Bichi R. 2008. Mixed approach to measuring social distance. Cognition, Brain, Behavior. An Interdisciplinary Journal. XII (4):487-508 [ Links ]

Bisschoff J. 1986. Church and Society, A testimony of the Dutch Reformed Church. NG Sendingpers. Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

Bisschoff J. 2008. Sewe 'reuse' en die NG Kerk: 'n truksvy ...? Kruisgewys. 8(2):10-12. [ Links ]

Coetzee J. s.a. Die onstaan en vorming van huidings en stereotipes teenoor lede van die buitegroep. University of the Free State. Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

De Gruchy J.W. 2010. Modern theology and the South African context: 1984-2010. Modern Theology 26(1):53-60. [ Links ]

Dolamo R.T.H. 2005. The church and society in South Africa celebrating first ten years of democracy (1994-2004). Verbum et ecclesia. 26(2): 326-340. [ Links ]

Gunaratnam Y. 2003. Researching 'Race' and Ethnicity. Methods, knowledge and power. Sage Publications: London. [ Links ]

Hamilton C.V., Huntley L., Alexander H., Guimaraes A.S.A.,& James W. 2001. Beyond racism. Race an inequality in Brazil, South Africa and the United States. Lynne Rienner publishers: London. [ Links ]

Jansen J.D. 2009a, 14 November. Jansen blames racism on the NGK. Weekend Argus, p1,3. [ Links ]

Jansen J.D. 2009b. Knowledge of the blood. Confronting race and the apartheid past. UCT Press: Cape Town. [ Links ]

Lever H. 1978. South African Society. Jonathan Ball Publishers: Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Ned Geref Kerk 1986. Kerk en Samelewing. Bloemfontein: Algemene Sinodale Kommissie. [ Links ]

Nelson J. 2002. The role the Dutch Reformed Church played in the rise and fall of apartheid. Journal of Hate Studies. 12: 63-70. [ Links ]

Osmer R.R. 2008. Practical Theology. An Introduction. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. Grand Rapids: Michigan. [ Links ]

Pieterse H., Scheepers P. & Van Der Ven J. 1991. Religious beliefs and ethnocentrism. Journal of Empirical Theology. 4(2): 64-84. [ Links ]

Ponton M.O. & Gorsuch R.L. 1988. Prejudice and religion revisited: A cross-cultural investigation with a Venezuelan sample. Journal for the Scientific study of Religion. 27(2): 260- 271. [ Links ]

Smith T., Bowman R., Hsu S.. 2007. Racial attitudes among Asian and European American college students: a cross-cultural examination. College Student Journal. 41(2): 436-443. [ Links ]

Snyman G.F. 2008. 'Is It not Sufficient to Be a Human Being?' Memory, Christianity and White Identity in Africa. Religion & Theology. 15(3/4):395-426. [ Links ]

Stevens G., Franchi V., Swart T. 2006. A race against time. Psychology and challenges to deracialisation in South Africa. ABC Press: Pretoria. [ Links ]

Vorster J.M. 2009. An ethics of forgiveness. Verbum et ecclesia. 30(1):365-383. [ Links ]

Wark C. & Galliher J.F. 2007. Emory Bogardus and the origins of the social distance scale. American Sociologist. 38(8): 383-395. [ Links ]

1 Part of this article was delivered by the author as a paper ("The racial divide in a South African church") at the SSSR conference in Tampa, Florida, USA on 2 November 2007.

2 Church Mirror reports and methodology

The methodology of these surveys is described in the different Church Mirror reports, available at the office of the General Synod of the DRC.

3 Confession of Belhar.

The Confession of Belhar was adopted by the Synod of the Dutch Reformed Mission Church in SA (DRMC) in 1986. This followed the declaration of a status confession in 1982 when the defence of apartheid on moral and theological grounds took place. The name Belhar in the Confession refers to the suburb where the meeting of the Synod took place. This Confession was also adopted by the DRCA when the DRMC and the DRCA unified in 1994. This confession also became part of the confessional basis of the newly formed church, called the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA).

APPENDIX