Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.29 n.2 Bloemfontein Dec. 2009

The interpretation and translation of Galatians 5:12

D.F. Tolmie1

ABSTRACT

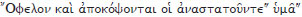

As is evident from commentaries on Galatians and from various English translations, scholars do not agree on the meaning, rhetorical labelling and translation of the wish expressed by Paul in Galatians 5:12 ( ). In this article various interpretations of this verse are considered; its rhetorical labelling is discussed; and suggestions are made as to the best way in which it may be translated into English.

). In this article various interpretations of this verse are considered; its rhetorical labelling is discussed; and suggestions are made as to the best way in which it may be translated into English.

Keywords: The Letter to the Galatians, Galatians 5:12, Interpretation, Translation, Sarcasm

Trefwoorde: Die Brief aan die Galasiërs, Galasiërs 5:12, Interpretasie, Vertaling, Sarkasme

1. INTRODUCTION

In Galatians 5:2ff., towards the end of his letter, Paul switches to a new rhetorical objective, namely to convince the Christians in Galatia to act in a particular way: They should not succumb to the pressure that his opponents in Galatia are placing on them to be circumcised; in future they should avoid them; and they should live according to the Spirit.2 In 5:2-6, the first section of this part of his letter, he begins by warning his readers not to be circumcised under any circumstances. In verses 2-4, three warnings are used to this effect, which are then followed by a positive exposition of his own views in verses 5-6. This section (5:2-6) is followed by another section, 5:7-12, in which the dominant rhetorical strategy changes to that of vilification of the opponents, with various strategies being used by Paul to achieve this effect.3 The latter section is then concluded in verse 12:  . This sentence is the focus of this article. As will be shown, it can be interpreted and translated in different ways. furthermore, its rhetorical labelling is approached in different ways by scholars. Accordingly, in this article the meaning and rhetorical labelling of verse 12 will be considered in depth. furthermore, various translations will be compared and suggestions will then be made as to the best way in which to translate the verse into English.

. This sentence is the focus of this article. As will be shown, it can be interpreted and translated in different ways. furthermore, its rhetorical labelling is approached in different ways by scholars. Accordingly, in this article the meaning and rhetorical labelling of verse 12 will be considered in depth. furthermore, various translations will be compared and suggestions will then be made as to the best way in which to translate the verse into English.

2. THE MEANING Of GALATIANS 5:12

The wish expressed by Paul in Galatians 5:12 (  ) may be classified as an attainable one.4 When one considers the interpretation of this verse, two expressions in particular deserve further scrutiny, namely

) may be classified as an attainable one.4 When one considers the interpretation of this verse, two expressions in particular deserve further scrutiny, namely  and

and  . I will begin with the second one. The words

. I will begin with the second one. The words  are used by Paul to describe his opponents in Galatia in a very negative way. BDAG (

are used by Paul to describe his opponents in Galatia in a very negative way. BDAG ( ) describe the meaning of this word, which is also used in the New Testament in Acts 17:6 and 21:38,5 as follows: "to upset the stability of a pers. or group, disturb, trouble, upset" (their emphasis), while Liddell and Scott (

) describe the meaning of this word, which is also used in the New Testament in Acts 17:6 and 21:38,5 as follows: "to upset the stability of a pers. or group, disturb, trouble, upset" (their emphasis), while Liddell and Scott ( ) describe it as "unsettle, upset". Louw and Nida (1988:288) place the word in a semantic domain that they describe as "hostility/strife" and in a sub-domain indicating "rebellion": "to cause people to rebel against or to reject authority." Thus, Paul is using a very negative description of his opponents - naturally so, because he is still continuing his vilification of them; at the same time, he is portraying the Christians in Galatia as their victims. According to him, the opponents do not have any good motives; in fact, they are destabilising the situation in the Christian congregations in Galatia.

) describe it as "unsettle, upset". Louw and Nida (1988:288) place the word in a semantic domain that they describe as "hostility/strife" and in a sub-domain indicating "rebellion": "to cause people to rebel against or to reject authority." Thus, Paul is using a very negative description of his opponents - naturally so, because he is still continuing his vilification of them; at the same time, he is portraying the Christians in Galatia as their victims. According to him, the opponents do not have any good motives; in fact, they are destabilising the situation in the Christian congregations in Galatia.

The other concept in verse 12 that deserves attention ( - future middle of

- future middle of  ) is normally used in the sense of "cut so as to make a separation, cut off, cut away" (BDAG

) is normally used in the sense of "cut so as to make a separation, cut off, cut away" (BDAG  ; their emphasis).6 Some examples from the New Testament and the LXX:7 In Mark 9:43 the word is used to refer to the cutting off of someone's hand and, two verses later, to the cutting off of someone's foot. In John 18:10 and 18:26 it is used to refer to the cutting off of the right ear of the servant of the high priest, while in Acts 27:32 it refers to the cutting off of the cords of a boat. In the LXX it is used several times in a similar way: Deuteronomy 25:12 (cutting off of someone's hand), Judges 1:6-7 (cutting off of someone's thumbs and big toes), 2 Samuel 10:4 (cutting off of garments), and Psalm 76:9 ("cutting off" of God's mercy). As these examples show, the word was often used to indicate the cutting off of body parts. In some instances it was also used in such a way that the cutting off of a man's private parts was implied, for example in Deuteronomy 23:2:

; their emphasis).6 Some examples from the New Testament and the LXX:7 In Mark 9:43 the word is used to refer to the cutting off of someone's hand and, two verses later, to the cutting off of someone's foot. In John 18:10 and 18:26 it is used to refer to the cutting off of the right ear of the servant of the high priest, while in Acts 27:32 it refers to the cutting off of the cords of a boat. In the LXX it is used several times in a similar way: Deuteronomy 25:12 (cutting off of someone's hand), Judges 1:6-7 (cutting off of someone's thumbs and big toes), 2 Samuel 10:4 (cutting off of garments), and Psalm 76:9 ("cutting off" of God's mercy). As these examples show, the word was often used to indicate the cutting off of body parts. In some instances it was also used in such a way that the cutting off of a man's private parts was implied, for example in Deuteronomy 23:2:

. 8 Translated literally, the word

. 8 Translated literally, the word  should be rendered in this instance as "the one (of whom it) had been cut off." Outside the New Testament, the word

should be rendered in this instance as "the one (of whom it) had been cut off." Outside the New Testament, the word  is sometimes used in a broader sense to indicate that something has been terminated. Stählin (1979:851-852) provides the following examples: termination of hope (Apoll. Rhod., IV, 1272), of pity (

is sometimes used in a broader sense to indicate that something has been terminated. Stählin (1979:851-852) provides the following examples: termination of hope (Apoll. Rhod., IV, 1272), of pity ( 76:8), of one's voice (Dion. Hal. Compos. Verb., 14) and of a period in time (Arist. Rhet., III, 8, 19).

76:8), of one's voice (Dion. Hal. Compos. Verb., 14) and of a period in time (Arist. Rhet., III, 8, 19).

If we turn our attention to the use of  in Galatians 5:12, it is clear from the context that Paul has in mind the removal of the private parts of his opponents. This can be seen from the fact that he refers to circumcision several times in the previous section (verses 2-6). In the verse directly preceding verse 12, he also refers to circumcision, and more specifically to people wrongly claiming that he was still proclaiming circumcision:

in Galatians 5:12, it is clear from the context that Paul has in mind the removal of the private parts of his opponents. This can be seen from the fact that he refers to circumcision several times in the previous section (verses 2-6). In the verse directly preceding verse 12, he also refers to circumcision, and more specifically to people wrongly claiming that he was still proclaiming circumcision:

The frequent mentioning of circumcision in the immediate context thus indicates that  in verse 12 should be interpreted in the sense of the physical removal of the private parts of the opponents. Literally the word thus means "they will have it cut off." If one reads verses 11 and 12 together, taking particular note of the

in verse 12 should be interpreted in the sense of the physical removal of the private parts of the opponents. Literally the word thus means "they will have it cut off." If one reads verses 11 and 12 together, taking particular note of the  at the beginning of verse 12, verse 12 may be interpreted as the climax of Paul's argument in this section. In fact, the

at the beginning of verse 12, verse 12 may be interpreted as the climax of Paul's argument in this section. In fact, the  at the beginning of verse 12 only makes sense in terms of a contrast between

at the beginning of verse 12 only makes sense in terms of a contrast between  and

and  (verses 2, 3, 11), that is, between circumcision and total removal of one's private parts (Stählin 1979:854).

(verses 2, 3, 11), that is, between circumcision and total removal of one's private parts (Stählin 1979:854).

That  should be understood in this sense, was already accepted by patristic exegetes such as John Chrysostom (Hom. 5:12), Theodore of Mopsuestia (in Gal.) and Augustine (exp. Gal.).9 It is also accepted by most commentators of our day.10 However, this was not always the case. Some of the early commentators interpreted it differently. As Meiser (2007:253) shows, Pelagius (in Gal.) interpreted the term metaphorically, as referring to the liberation from evil ways, and Maximus Confessor (qu. dub. I,77) construed it as an indication of the hope of penance, whereas Ambrosiaster (in Gal.) understood it as referring to the exclusion of salvation. In the Vulgate it was translated in a more general way (ultinam et abscidantur qui vos conturbant), reflecting an interpretation of

should be understood in this sense, was already accepted by patristic exegetes such as John Chrysostom (Hom. 5:12), Theodore of Mopsuestia (in Gal.) and Augustine (exp. Gal.).9 It is also accepted by most commentators of our day.10 However, this was not always the case. Some of the early commentators interpreted it differently. As Meiser (2007:253) shows, Pelagius (in Gal.) interpreted the term metaphorically, as referring to the liberation from evil ways, and Maximus Confessor (qu. dub. I,77) construed it as an indication of the hope of penance, whereas Ambrosiaster (in Gal.) understood it as referring to the exclusion of salvation. In the Vulgate it was translated in a more general way (ultinam et abscidantur qui vos conturbant), reflecting an interpretation of  in the sense of a removal from the church (Longenecker 1990:234). Erasmus also interpreted it in this way,11 whereas Luther understood it as a reference to utter destruction and translated it as follows: "Wollt Gott, das sie außgerottet wurden, die euch verstoren."12

in the sense of a removal from the church (Longenecker 1990:234). Erasmus also interpreted it in this way,11 whereas Luther understood it as a reference to utter destruction and translated it as follows: "Wollt Gott, das sie außgerottet wurden, die euch verstoren."12

In this regard, Ramsay also objects to the almost complete unanimity of his time, according to which  is interpreted in the sense of the physical removal of the private parts of the opponents. He does not believe that Paul "would have yielded so completely to pure ill-temper ... The scornful expression would be a pure insult, as irrational as it is disgusting" (Ramsay [1900] 1965:439). However, such an argument concerning what would have been proper for Paul to say and what would not (which may also underlie some of the other instances in which scholars make the same choice as Ramsay), is not a good one. In the light of the arguments in respect of the context outlined above, and the way in which the word was normally used in Greek literature, one can safely assume that the best interpretation of the word is that it refers to having one's private parts removed.

is interpreted in the sense of the physical removal of the private parts of the opponents. He does not believe that Paul "would have yielded so completely to pure ill-temper ... The scornful expression would be a pure insult, as irrational as it is disgusting" (Ramsay [1900] 1965:439). However, such an argument concerning what would have been proper for Paul to say and what would not (which may also underlie some of the other instances in which scholars make the same choice as Ramsay), is not a good one. In the light of the arguments in respect of the context outlined above, and the way in which the word was normally used in Greek literature, one can safely assume that the best interpretation of the word is that it refers to having one's private parts removed.

3. LABELLING THE RHETORICAL TECHNIqUE IN GALATIANS 5:12

If the interpretation of Galatians 5:12 as set out above is correct, the verse can obviously not be taken literally and, instead, functions as an example of a rhetorical technique. If one surveys the literature on this verse, it is striking that scholars label this technique in quite different ways. The following representative list indicates the differences in this regard: "irony" (Lightfoot 1921:207); "schärfster Sarkasmus" (Lietzmann 1971:38); "ein gänzlich irrealer, höhnisch gereizter Wunsch ... reiner Spott und Hohn" (Von Campenhausen 1954:191); "grimmiger Spott" (Schlier 1971:240); "bittere Ironie und ... Sarkasmus" (Rohde 1989:224); "sarcastic and indeed 'bloody' joke" (Betz 1979:270); "sarcastic und dismissive snort" (Dunn 1995:282); "invective" (Witherington 1998:374); "ridiculing curse" (Russell 1998:432); "a rude, obscene, and literally bloody picture at their expense" (Martyn 1997:478); "ein Witz" (Vouga 1998:126); "schlecht[er] Witz" (Mitternacht 1999:85); "voller sarkastischer und bissiger Polemik" (kremendahl 2000:247); and "a joke" (Hietanen 2005:167).

In which way do these labels differ from one another? The primary difference seems to lie in the way in which Paul's objective in this verse is interpreted. Broadly speaking, the interpretations range from a view in terms of which the objective is construed as being more gentle (irony, a joke) to an interpretation which regards it as being much harsher, and even rude (sarcasm, dismissive snort, ridiculing curse). What, then, would then be the best way to label this verse rhetorically? Let us take irony and sarcasm - which seem to represent the opposite ends of the various possibilities mentioned above - as a point of departure. (Of course, strictly speaking, it is not entirely correct to view these two factors as opposites, since nowadays13 sarcasm is quite often regarded as a particular [extreme] form of irony.)

Irony can be generally defined as expressing the opposite of what one actually means (See, for example, Dupriez 1991:243). If one wishes to narrow the definition down a little further, one may follow Dunmire and kaufer (1996:356), who use the following taxonomy of Donald Muecke for the identification of irony: firstly, it is a phenomenon consisting of two layers - one as it appears to be and the other one as it really is; secondly, these two layers are in an oppositional relationship to one another, in the sense that they contradict one another, and are incompatible or incongruous; and, thirdly, a degree of "innocence" is present in the sense that the victim of the irony is not aware of the discrepancy between the two layers, or owing to the fact that the speaker/ author pretends that there is no discrepancy between the two layers. quite often, a further distinction is made between verbal irony and situational irony: In the case of verbal irony, the speaker/author deliberately creates the irony whereas in situational irony a particular situation is perceived by an observer/ reader as being ironic (Dunmire & kaufer 1996:356).

Whereas irony is usually described in terms of broad categories such as those outlined above, sarcasm is normally identified more narrowly. for example, Dupriez (1991:407) defines it as: "Aggressive, frequently cruel mockery."

When irony and sarcasm are being correlated by scholars, the same tendency can be seen:

Irony is always a discrepancy between what is said literally and what the statement actually means. On the surface the ironical statement says one thing, but it means something rather different. In a light-hearted, laughingly ironical statement, the literal meaning may be only partially qualified; in a bitter and obvious irony (such as sarcasm), the literal meaning may be completely reversed (Brooks and Warren 1979:479).

In this regard, kreuz and Glucksberg (1989:374-386)14 argue that in the case of sarcasm, there is a specific victim of the ridiculing, whereas in irony there is no particular victim.

For the purpose of this article, I will thus proceed from the point of departure that the main difference between categories such as "irony", "joke" and "sarcasm", in the context of a rhetorical labelling of Galatians 5:12, is related to the level of harshness that one detects in this verse.15 If one regards it as a mild form of irony or a joke, the effect is viewed as rather innocent. for example, Hietanen (2005: 167), who regards the wish expressed by Paul as a joke, describes its effect as the creation of a pause - "a presentational device" as Hietanen calls it - which generates "relief and a pause." On the other hand, if one views Paul's utterance in terms of a harsh form of irony, e.g. sarcasm, its aim is perceived to be much less innocuous.

To make a decision in this regard, it seems best to investigate the context within which Paul's pronouncement is used.16 If one looks at Paul's rhetorical strategy in the section directly preceding verse 12, he seems to be quite agitated. for example, in verses 2-4 he employs three very strict warnings:

If you let yourselves be circumcised, Christ will be of no benefit to you; Everyone who lets himself be circumcised, is forced to obey the entire law!; You who want to be justified by the law have cut yourselves off from Christ! You have fallen away from grace!

The content of these warnings indicates a high level of distress.

Furthermore, in verses 7-12 Paul also uses various strategies to vilify his opponents (see footnote 3 of this article for details). The aims of vilification, a widespread phenomenon in early Christian epistolography and in the Mediterranean world, can hardly be described as innocent.17 The repeated use of vilification as a rhetorical technique in these verses is thus also indicative of a high level of agitation on Paul's part. further evidence in this regard is the fact that Paul even threatens that the opponents will be punished by God (verse 10). Thus, the general atmosphere of verses 2-12 seems to be of such a nature that it is unlikely that Paul would be using irony in a light-hearted way in verse 12. His utterance in verse 12 should thus rather be classified as a harsh form of irony, namely as sarcasm.

Why would Paul be using sarcasm? Besides the fact that sarcasm may provide a way of expressing his bitter feelings regarding the opponents, it is also a powerful technique for increasing the distance between his audience and the opponents: Against the background of public disgust for rituals such as emasculation, he uses this verse to create disgust towards the opponents (Betz 1979:270). There may possibly be one or two underlying notions embedded in Paul's use of sarcasm in this instance, namely that if they were emasculated, they would become like the priests of Cybele (who were willingly castrated), or that (in terms of the Jewish law) they would (ironically!) have to be excluded from the worshipping assembly18 (see, for example, Dunn 1995:283 and Jónson 1965:267-268). However, there is no real need to posit such allusions here (as, correctly, pointed out by Bruce 1982:238; cf. also Betz 1979:270). The primary aim of Paul's utterance may thus be identified as a sarcastic dismissal of the opponents' insistence on circumcision.

4. TRANSLATING GALATIANS 5:12

The best way to translate Galatians 5:12 will now be investigated. Below is a representative group of English translations19 which will be used as an indication of how Bible translators render this verse. In the evaluation of these translations, the fact that different translation strategies were followed will be kept in mind. for example, consideration will be given to the question as to whether the translation strategy followed required the translators to keep as close as possible to the source text, or whether they had more freedom to take the reception of the translation in the target culture into account. The evaluation will be based on the viewpoints expressed earlier on in the article and will focus on the various facets that have been highlighted thus far. It will conclude with a suggestion as to the best way in which the verse can be translated.

I would that they that unsettle you would even go beyond circumcision (ASV).

My desire is that they who give you trouble might even be cut off themselves (BBE).

I would that they would even cut themselves off who throw you into confusion (DBY).

I would they were even cut off, who trouble you (DRA).

I wish those who unsettle you would emasculate themselves! (ESV).

I would they were even cut off which trouble you (kJV).

Would that those who are upsetting you might also castrate themselves! (NAB).

Would that those who are troubling you would even mutilate them selves (NAS).

As for those agitators, I wish they would go the whole way and emasculate themselves! (NIB/NIV).

I could wish that those who are unsettling you would go further and mutilate themselves (NJB).

I could wish that those who trouble you would even cut themselves off! (NkJ).

I only wish that those troublemakers who want to mutilate you by circumcision would mutilate themselves (NLT).

I wish those who unsettle you would castrate themselves! (NRS).

I wish those who unsettle you would mutilate themselves! (RSV).

I would they were even cut off who trouble you (RWB).

I wish that the people who are upsetting you would go all the way; let them go and castrate themselves (TEV).

I would they were even cut off who trouble you (WEB).

O that even they would cut themselves off who are unsettling you! (YLT).

4.1 In the discussion of Galatians 5:12 earlier on, it was indicated that the wish expressed in this verse should be classified as an attainable one. This aspect is conveyed quite well by most of the translations above, the best of which are "My desire ...", "I wish ...", "(I) (w)ould that ..." and "O that ...". Less successful seems to be the rendering "I could wish" (NJB/NkJ), which expresses the sentiment more tentatively than in the case of the Greek.

4.2 The phrase  has been interpreted earlier on in this article as indicating that, according to Paul's views, the opponents were trying to upset the stability of the Christian churches in Galatia. This aspect has been rendered faithfully in almost all the translations above: "unsettle you," "give you trouble," "throw you into confusion," "upset you" and "troublemakers." In two instances, however, the translation seems a little too far removed from the Greek text. The NIB/NIV uses "agitators" to translate the Greek phrase, but this leaves the direct object (

has been interpreted earlier on in this article as indicating that, according to Paul's views, the opponents were trying to upset the stability of the Christian churches in Galatia. This aspect has been rendered faithfully in almost all the translations above: "unsettle you," "give you trouble," "throw you into confusion," "upset you" and "troublemakers." In two instances, however, the translation seems a little too far removed from the Greek text. The NIB/NIV uses "agitators" to translate the Greek phrase, but this leaves the direct object ( ) untranslated. Compared to the other examples cited, the NIB/NIV rendering is thus less successful. The NLT translates

) untranslated. Compared to the other examples cited, the NIB/NIV rendering is thus less successful. The NLT translates  as "those troublemakers who want to mutilate20 you by circumcision." This seems rather far removed from the Greek - even for a translation focusing on the target culture. Although the translators succeeded in making it very easy for the intended readers to grasp the (implicit) link between this verse and the previous one (circumcision), the question should be raised as to whether this translation does not represent an instance of "explicitation", i.e. the tendency among some translators to use a more expressive item in the translation than the one used in the source language (cf. Naudé 2000:18).

as "those troublemakers who want to mutilate20 you by circumcision." This seems rather far removed from the Greek - even for a translation focusing on the target culture. Although the translators succeeded in making it very easy for the intended readers to grasp the (implicit) link between this verse and the previous one (circumcision), the question should be raised as to whether this translation does not represent an instance of "explicitation", i.e. the tendency among some translators to use a more expressive item in the translation than the one used in the source language (cf. Naudé 2000:18).

4.3  is rendered quite differently in the various translations above. In some of the instances, the word is translated wrongly as indicating that Paul wishes that his opponents would separate themselves from the Galatian churches: "... would be cut off themselves," "... cut themselves off" and "... were even cut off." As argued above, such a translation does not reflect the way in which this word is actually used in this particular context.

is rendered quite differently in the various translations above. In some of the instances, the word is translated wrongly as indicating that Paul wishes that his opponents would separate themselves from the Galatian churches: "... would be cut off themselves," "... cut themselves off" and "... were even cut off." As argued above, such a translation does not reflect the way in which this word is actually used in this particular context.

Translators following the other option (  interpreted as "they will have it cut off") use words such as "mutilate themselves", "emasculate themselves", "castrate themselves" and "... would even go beyond circumcision". Of these renderings, the first option is the least successful, since "mutilate" has a much more general meaning than the notion conveyed by the Greek word.21 The second and the third options render the meaning faithfully, but the question should be raised as to whether the specific words chosen to translate the Greek do not lose something of the vagueness of the Greek expression, since "emasculate" and "castrate" seem to be more explicit than the Greek

interpreted as "they will have it cut off") use words such as "mutilate themselves", "emasculate themselves", "castrate themselves" and "... would even go beyond circumcision". Of these renderings, the first option is the least successful, since "mutilate" has a much more general meaning than the notion conveyed by the Greek word.21 The second and the third options render the meaning faithfully, but the question should be raised as to whether the specific words chosen to translate the Greek do not lose something of the vagueness of the Greek expression, since "emasculate" and "castrate" seem to be more explicit than the Greek  ("to have it cut off"). In this sense, the last option ("...would even go beyond circumcision") is more successful; but, on the other hand, it could also be regarded as being too general. The best translation seems to be "to have everything cut off."

("to have it cut off"). In this sense, the last option ("...would even go beyond circumcision") is more successful; but, on the other hand, it could also be regarded as being too general. The best translation seems to be "to have everything cut off."

Furthermore, it should also be pointed out that all the translations that interpret  as referring to emasculation, translate it in such a way that Paul seems to be stating that his opponents would emasculate themselves. 22 However, as BDf (§317)23 quite rightly point out, the word is in the middle voice and should thus be understood here in the sense of "let oneself be" ("sich ... lassen"). Apart from

as referring to emasculation, translate it in such a way that Paul seems to be stating that his opponents would emasculate themselves. 22 However, as BDf (§317)23 quite rightly point out, the word is in the middle voice and should thus be understood here in the sense of "let oneself be" ("sich ... lassen"). Apart from  in Galatians 5:12, they also refer to several other instances in the New Testament where the middle voice should be interpreted in this way: Luke 2:1, 3, 5; Acts 21:24; 22:16; 1 Cor. 6:11; 10:2; 11:6.

in Galatians 5:12, they also refer to several other instances in the New Testament where the middle voice should be interpreted in this way: Luke 2:1, 3, 5; Acts 21:24; 22:16; 1 Cor. 6:11; 10:2; 11:6.  in Galatians 5:12 should thus be translated as "they will have it cut off" (or: "they will have themselves emasculated/castrated", if one prefers to use these words in one's translation), and not as "they will cut it off/emasculate/castrate themselves."

in Galatians 5:12 should thus be translated as "they will have it cut off" (or: "they will have themselves emasculated/castrated", if one prefers to use these words in one's translation), and not as "they will cut it off/emasculate/castrate themselves."

4.4 In section 2, I argued that the word  is very important for a proper understanding of the link between verse 12 and the previous verse, and in particular of the contrast between verses 12 and 11, which plays a fundamental role in creating the sarcastic effect. In a few of the translations above, this word has not been translated (ESV, NRS, RSV), which should be indicated as a deficiency. Most translations translate it as "even", which seems to be the only choice if one wishes to use only one word to translate the term into English. The NAB's "also" is not a good choice, because "also" might be interpreted by the intended reader as indicating something additional, rather than as indicating a climax. In the case of the NIB/NIV ("they would go the whole way..."), NJB ("would go further and ...") and TEV ("go all the way ..."),

is very important for a proper understanding of the link between verse 12 and the previous verse, and in particular of the contrast between verses 12 and 11, which plays a fundamental role in creating the sarcastic effect. In a few of the translations above, this word has not been translated (ESV, NRS, RSV), which should be indicated as a deficiency. Most translations translate it as "even", which seems to be the only choice if one wishes to use only one word to translate the term into English. The NAB's "also" is not a good choice, because "also" might be interpreted by the intended reader as indicating something additional, rather than as indicating a climax. In the case of the NIB/NIV ("they would go the whole way..."), NJB ("would go further and ...") and TEV ("go all the way ..."),  is translated by a phrase, which conveys the meaning faithfully.

is translated by a phrase, which conveys the meaning faithfully.

4.5 A minor point that should be raised concerns the use of punctuation marks in the English translations above. Some of the translations use an exclamation mark at the end of the sentence, whereas some only use a full stop. The use of an exclamation mark is better, because it may help the intended reader to grasp the sarcastic tone of the sentence, as well as the fact that Paul is apparently very agitated in this section.

4.6 Lastly, a suggestion as to the best way in which this verse can be rendered in English, is warranted here. On the basis of the evaluation of the various English translations above and the arguments raised earlier in this article with regard to the interpretation of this verse, the best translation for translators attempting to adhere as closely as possible to the source text would seem to be: "I wish that those who upset you, would even have everything cut off!" Translators who follow a strategy which does not require them to adhere closely to the source text, could translate the verse as follows: "I wish that those who upset you, would go the whole way and have everything cut off!"

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANDERSON, R.D. 2000. Glossary of Greek rhetorical terms connected to the methods of argumentation, figures and tropes from Anaximenes to Quintilian. Leuven: Peeters. CBET 24. [ Links ]

ARICHEA, D.C. & NIDA, E.A. 1975. A translators handbook on Paul's Letter to the Galatians. s.l.: UBS. [ Links ]

BETZ, H.D. 1979. Galatians. A commentary on Paul's Letter to the Galatians. Philadelphia: fortress. Hermeneia. [ Links ]

BLUHM, H. 1984. Luther. Translator of Paul. Studies in Romans and Galatians. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

BROOKS, C. & WARREN, R.P. 1979. Modern rhetoric. Fourth revised edition. New York: Harcourt - Brace & World. [ Links ]

BRUCE, F.F. 1982. The Epistle to Galatians. A commentary on the Greek text. Exeter: Paternoster Press. NIGTC. [ Links ]

BURTON, E. DE W. 1962. A critical and exegetical commentary on the Epistle of the Galatians. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. ICC. [ Links ]

CHEANG, H.S. & PELL, M.D. 2008. The sound of sarcasm. Speech Communication 50:366-381. [ Links ]

DUNMIRE, P.L. & KAUFER, D.S. 1996. Irony. In: T. Enos (ed.), Encyclopedia of rhetoric and composition. Communication from ancient times to the information age (New York: Garland Publishing), pp. 355-357. [ Links ]

DUNN, J.D.G. 1995. The Epistle to the Galatians. Peabody: Hendrickson. BNTC. [ Links ]

DUPRIEZ, B. 1991. A dictionary of literary devices. Translated and adapted by Albert W. Halsall. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

DU TOIT, A.B. 1994. Vilification as a pragmatic device in early Christian epistolography. Bib 75: 403-412. [ Links ]

GERRIG, R.J. 2000. Additive effects in the perception of sarcasm: Situational disparity and echoic mention. Metaphor & Symbol 15:197-208. [ Links ]

GIORA, R. 2000. Differential effects of right- and left-hemisphere damage on understanding sarcasm and metaphor. Metaphor & Symbol 15:63-83. [ Links ]

GOOD, E.M. 1965. Irony in the Old Testament. London: SPCK. [ Links ]

HIETANEN, M. 2005. Paul's argumentation in Galatians. A pragma-dialectical analysis of Gal. 3.1 5.12. Helsinki: Helsinki University Printing House. [ Links ]

JÓNSON, J. 1965. Humour and irony in the New Testament. Illuminated by parallels in Talmud and Midrash. Reykjavik: Menningarsjóds. [ Links ]

KATZ, A.N, BLASKO, D.G. & KAZMERSKI, V.A. 2004. Saying what you don't mean. Current Directions in Psychological Science 13:186-189. [ Links ]

KRÄMER, H. 1989. Zur Bedeutung von Wunschsätzen im Neuen Testament. In: D.-A. koch, G. Sellin & A. Lindemann (eds.), Jesu Rede von Gott und ihre Nachgeschichte im frühen Christentum. Beiträge zur Verkündigung Jesu und zum Kerygma der Kirche. Festschrift für Willi Marxsen zum 70. Geburtstag (Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn), pp. 375-378. [ Links ]

KREMENDAHL, D. 2000. Die Botschaft der Form. Zum Verständnis von antiker Epistolografie und Rhetorik im Galaterbrief. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. NTOA 46. [ Links ]

KREUZ, R.J. & GLUCKSBERG, S. 1989. How to be sarcastic: The echoic reminder theory of verbal irony. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 118:374-386. [ Links ]

LAUSBERG, H. 1998. Handbook of literary rhetoric. A foundation for literary study. Translated by Matthew T. Bliss, Annemiek Jansen, David E. Orton and edited by David E. Orton & R. Dean Anderson. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

LEE, C.J. & KATZ, A.N. 1998. The differential role of ridicule in sarcasm and irony. Metaphor & Symbol 13:1-15. [ Links ]

LIDDELL, H.G. & SCOTT, R. 1996. A Greek-English lexicon. With a revised supplement. Oxford: Clarendon. [ Links ]

LIETZMANN, H. 1971. An die Galater. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr. HNT 10. [ Links ]

LIGHTFOOT, J.B. 1921. Saint Paul's Epistle to the Galatians. A revised text with introduction, notes, and dissertations. London: MacMillan. [ Links ]

LONGENECKER, R.N. 1990. Galatians. Dallas: Word Books. Word 41. [ Links ]

LOUW, J.P. & NIDA, E.A. 1988. Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament based on semantic domains. Volume 1. Introduction and domains. New York: United Bible Societies. [ Links ]

LÜHRMANN, D. 1988. Der Brief an die Galater. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag. ZBK. [ Links ]

MARTYN, J.L. 1997. Galatians. A new translation with introduction and commentary. New York: Doubleday. Anchor Bible 33A. [ Links ]

MEISER, M. 2007. Galater. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. NTP 9. [ Links ]

MEYER, H.A.W. 1873. Critical and exegetical handbook to the Epistle to the Galatians. Translated from the fifth edition of the German by G.H. Venables. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

MITTERNACHT, D. 1999. Forum für Sprachlose. Eine kommunikationspsychologische und epistolärrhetorische Untersuchung des Galaterbriefs. Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell International. CB NTS 30. [ Links ]

MUSSNER, F. 1977. Der Galaterbrief. freiburg: Herder. HThk 9. [ Links ]

NAUDÉ, J.A. 2000. Translation studies and Bible Translation. Acta Theologica 20:1-27. [ Links ]

PLUMER, E. 2003. Augustine's commentary on Galatians. Introduction, text, translation and notes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Oxford Early Christian Studies. [ Links ]

RAMSAY, W. 1965 [1900]. A historical commentary on St. Paul's Epistle to the Galatians. Grand Rapids: Baker. [ Links ]

REEVE, A.E. & SCREECH, M.A. 1993. Erasmus' annotations on the New Testament. Galatians to the Apocalypse. Facsimile of the final Latin text with all earlier variants. Edited by Anne Reeve. Introduction by M.A. Screech. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

ROHDE, J. 1989. Der Brief des Paulus an die Galater. Berlin: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt. ThHK. [ Links ]

RUSSELL, D.M. 1998. The strategy of a first-century appeals letter: A discourse reading of Paul's Epistle to Philemon. Journal of Translation and Textlinguistics 11:1-25. [ Links ]

SCHEWE, S. 2005. Die Galater zurückgewinnen. Paulinische Strategien in Galater 5 und 6. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. FRLANT 208. [ Links ]

SCHLATTER, A. 1930. Erläuterungen zum Neuen Testament, II. Stuttgart: Calwer. [ Links ]

SCHLIER, H. 1971. Der Brief an die Galater. Berlin: Evangelische Verlag. KEK 17. [ Links ]

SCHWOEBEL, J., DEWS, S., WINNER, E. & SRINIVAS, K. 2000. Obligatory processing of the literal meaning of ironic utterances: further evidence. Metaphor & Symbol 15:47-61. [ Links ]

SIDER, R.D. (ED.) 1984. Collected works of Erasmus. New Testament Scholarship. Paraphrases on Romans and Galatians. Translated and annotated by J.B. Payne, A. Rabil Jr. & W.S. Smith. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ Links ]

STÄHLIN, G. 1979.  . TWNT 3:851-855. [ Links ]

. TWNT 3:851-855. [ Links ]

TOLMIE, D.F. 2005. Persuading the Galatians. A text-centred rhetorical analysis of a Pauline letter. Tübingen: Mohr-Siebeck. WUNT 190. [ Links ]

VON CAMPENHAUSEN, H. 1954. Ein Witz des Apostels Paulus und die Anfänge des christlichen Humors. In: W. Eltester (red.), Neutestamentliche Studien für Rudolf Bultmann zu seinem siebzigsten Geburtstag (Berlin: Töpelmann, BZNW 21), pp. 189-193. [ Links ]

VOUGA, F. 1998. An die Galater. Tübingen: Mohr-Siebeck. HNT 10. [ Links ]

WINER, G.B. & MOULTON, W.F. 1882. A treatise on the grammar of the New Testament Greek regarded as a sure basis for New Testament exegesis by Dr. G. B. Winer. Translated from the German, with large editions and full indices by Rev. W.f. Moulton MA, DD. Third edition, revised. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

WITHERINGTON, B. 1998. Grace in Galatia. A commentary on St. Paul's Letter to the Galatians. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

ZERWICK, M. 2001 [1963]. Biblical Greek. Illustrated by example by Maximilian Zerwick S.J. English edition adapted from the fourth Latin edition by Joseph Smith. Seventh reprint. Roma: E.P.I.B. SPIB 114. [ Links ]

Prof. D.F. Tolmie, Dean: Faculty of Theology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, 9300.

1 It is a pleasure to dedicate this article to Prof. fanie Riekert, who was one of my lecturers in Greek when I was a student, and afterwards was one of my colleagues at the faculty of Theology for a long time. This article is based on work supported by the National Research foundation of South Africa.

2 According to my view (see Tolmie 2005), Paul's overall rhetorical strategy in the Letter to the Galatians can be summarised in terms of the following six rhetorical objectives: To convince the audience of his divine authorisation (1:1-2:10); to convince them that his gospel is the true gospel (2:11-3:14); to convince them of the inferiority of the law (3:15-25); to convince them that the "gospel" of the opponents represents spiritual slavery and urge them, instead, to remain spiritually free by adhering to his gospel (3:26-5:1); to convince them to act as he wishes them to: not to succumb to the pressure to be circumcised; to avoid the opponents, and to live according to the Spirit (5:2-6:10); and, lastly, to finally refute the opponents (6:11-18).

3 He uses the following strategies: In verse 7 his opponents are portrayed as people who prevent the Galatians from obeying the truth; in verse 8 the opponents are depicted as acting against God; in verse 9 a proverb is used to associate them/ their views with leaven, thereby suggesting a process of corruption; in verse 10b they are (collectively) described as  and portrayed as people who will be punished by God, and in verse 12 they are described as

and portrayed as people who will be punished by God, and in verse 12 they are described as

4 According to BDR §359.1 (note 2),  followed by a future indicative indicates an attainable wish, or, in this case, as Zerwick (2001 [1963]:123) explains: "a desire possible of attainment but not seriously entertained." krämer (1989:375-378), followed by Vouga (1998:126), prefers to classify Galatians 5:12 as an unattainable wish.

followed by a future indicative indicates an attainable wish, or, in this case, as Zerwick (2001 [1963]:123) explains: "a desire possible of attainment but not seriously entertained." krämer (1989:375-378), followed by Vouga (1998:126), prefers to classify Galatians 5:12 as an unattainable wish.

5 See also Daniel 7:23 in the LXX.

6 See also Louw and Nida (1988:§19.18) and Liddell and Scott (1996:  ).

).

7 The word is used in a similar way in Greek literature outside the New Testament and the LXX. See, for instance, the examples cited by BDAG (  ): Homer, Hdt. 6, 91; Diod. S. 17, 20, 7; Jos., Bell. 6, 164, Vi. 177; Epict. 2, 5, 24; Od. 10, 127; X., Hell. 1, 6, 21; Polyaenus 5, 8, 2; 6, 8; Hs 9, 9, 2. See also Liddell and Scott (1996:

): Homer, Hdt. 6, 91; Diod. S. 17, 20, 7; Jos., Bell. 6, 164, Vi. 177; Epict. 2, 5, 24; Od. 10, 127; X., Hell. 1, 6, 21; Polyaenus 5, 8, 2; 6, 8; Hs 9, 9, 2. See also Liddell and Scott (1996:  ) and Stählin (1979:851-853).

) and Stählin (1979:851-853).

8 Cf. also the following examples of this use cited by BDAG (  ): Lucian, Eunuch. 8; Cass. Dio 79, 11; Philo, Leg. All. 3, 8, Spec. Leg. 1, 325; Epict. 2, 20, 19.

): Lucian, Eunuch. 8; Cass. Dio 79, 11; Philo, Leg. All. 3, 8, Spec. Leg. 1, 325; Epict. 2, 20, 19.

9 Take note that Augustine interprets this verse as a blessing and not as a curse, because he wants to safeguard Paul against violating Matthew 5:44. See the discussion by Plumer (2003:92, 202-203) in this regard.

10 See, for example, Lightfoot (1921:207), Burton (1962:288), Schlier (1971:240), Mussner (1977:363), Betz (1979:270), Bruce (1982:238), Lührmann (1988:83), Longenecker (1990:234), Witherington (1998:373), Dunn (1995:282-284), Martyn (1997:479) and Schewe (2005:81). See also Meyer (1873:301) for a long list of scholars of the nineteenth century who interpreted it in the same way. There are not many scholars of our time who interpret it differently, but see Schlatter (1930:130), who interprets it as a reference to God's judgement.

11 From his annotation to this text it is clear (cf. Reeve & Screech 1993:585-586) that Erasmus was aware that abscindantur could be interpreted in two ways, namely as indicating either that Paul's opponents may be cut off from grace or that they may be castrated. He was also aware that Ambrose, Chrysostom and Theophylact interpreted it in the second sense; but he preferred to interpret it in the first sense, as, according to him, it was more worthy of the apostle's dignity. (A word of appreciation is due, at this point, to Dr. J.f.G. Cilliers of the University of the free State, who assisted me with the interpretation of Erasmus' annotation to this verse.) See also Erasmus' paraphrase of Galatians in this regard (Sider 1984:124). Meyer (1873:302) also mentions the following scholars who interpreted the expression in this way: Beza, Piscator, Cornelius a Lapide, Bengel, Michaelis, Zachariae and Morus.

12 This is a quotation from his 1522 translation. The 1546 translation is similar: "Wolte Gott, das sie auch ausgerottet würden, die euch verstören." (Cf. Bluhm 1984:498499.) Interestingly enough, in his lectures on Galatians in 1519 (WA 2.573), Luther interpreted  as referring to emasculation, but in his lectures of 1535 (WA 40.II,2,56b) he interpreted it as referring to total destruction. In his commentary on Galatians, Calvin (CO 50) interpreted the term in a similar way to that in which Luther did so in 1535: "... nam exitium imprecatur impostoribus illis a quibus decepti fuerant Galatae. "

as referring to emasculation, but in his lectures of 1535 (WA 40.II,2,56b) he interpreted it as referring to total destruction. In his commentary on Galatians, Calvin (CO 50) interpreted the term in a similar way to that in which Luther did so in 1535: "... nam exitium imprecatur impostoribus illis a quibus decepti fuerant Galatae. "

13 For a brief but informative overview of the way in which the views on irony developed since the concept first appeared in Plato's Republic, see Dunmire and kaufer (1996:355-357). See also Lausberg (1998:§582), who refers to the following principles that were used to classify various forms of irony: quintilian (Inst. 8.6.55) divided irony in terms of its purpose: praise vs. censure; Trypho (Trop. iii) divided it in terms of the persons concerned ("stranger-irony" and "self-irony"); while Rufinus (Rufin. 1-7) classified it in terms of the level of energy which was involved:  ,

,  . from the last example, it can be seen that sarcasm was sometimes regarded as one of the harshest forms of irony. The term "sarcasm" itself is already an indication of this, since it comes from the Greek word

. from the last example, it can be seen that sarcasm was sometimes regarded as one of the harshest forms of irony. The term "sarcasm" itself is already an indication of this, since it comes from the Greek word  , denoting the tearing of flesh by dogs (Liddell & Scott 1996:

, denoting the tearing of flesh by dogs (Liddell & Scott 1996:  ). Nevertheless, it also appears that, in ancient times, the term

). Nevertheless, it also appears that, in ancient times, the term  did not always have the extremely negative emotional connotations that are associated with it today (especially with regard to the aim of hurting someone else). for example, it was viewed in Ps.-Plu. Vit.Hom 69 and Tryph. Trop. 2.20 as something that was "effected when someone (was) reproached using opposite terms with a false smile" (cf. Anderson 2000:108). Also take note that

did not always have the extremely negative emotional connotations that are associated with it today (especially with regard to the aim of hurting someone else). for example, it was viewed in Ps.-Plu. Vit.Hom 69 and Tryph. Trop. 2.20 as something that was "effected when someone (was) reproached using opposite terms with a false smile" (cf. Anderson 2000:108). Also take note that  was sometimes regarded as almost identical to

was sometimes regarded as almost identical to  . Cf. Anderson (2000:126).

. Cf. Anderson (2000:126).

14 See also the research of Lee and katz (1998:1-15), who confirm this distinction on the basis of experiments conducted on a group of undergraduates.

15 In this regard, see also the following remark by Good (1965:27):

Invective and sarcasm have in common the aim not only to wound but to destroy. I would distinguish them from irony, because I do not believe that irony, properly so called, is meant to destroy... [T]he basis of irony in a vision of truth means that irony aims at amendment of the incongruous rather than its annihilation.16 Basing one's choice only on a written version of a letter makes the process even more difficult, because valuable clues as to a speaker's intent are lost when such an utterance is reduced to a written form. In this regard, see the research by Cheang and Pell (2008:366-381). On the complex processes that are generally involved when irony or sarcasm has to be detected by listeners/readers, see the research by Gerrig (2000:197-208), Giora (2000:63-83), Schwoebel et al. (2000:47-61) and katz, Blasko and kazmerski (2004:186-189).

17 On the use of vilification in early epistolography, see Du Toit (1994:403-412), and on its use in Galatians, see Mitternacht (1999:291-299).

18 See, for example, Dunn (1995:283):

The wish then is a savage one: would that the knife might slip in the hand of those who count circumcision indispensable to participation in the assembly of the Lord, so that they might find the same rules excluding themselves. Paul expresses the wish that a rite understood as one of dedication and commitment to Yahweh might become one which excluded from the presence of Yahweh (in the worshipping assembly).19 All translations in the list have been quoted from BibleWorks, with the exception of the TEV version. for the meaning of the abbreviations, see the list at the end of this article.

20 For criticism of the use of the word "mutilate", see the discussion in 4.3.

21 That this is the case can be seen from the way in which the word "mutilate" is explained in the Oxford English Dictionary (Online edition; accessed January 9, 2009): 1. trans. To render (a thing, esp. a book or other document) imperfect by cutting out or excising a part; to change or destroy part of the content or meaning of. 2. trans. To deprive (a person or animal) of the use of a limb or bodily organ, by dismemberment or otherwise; to cut off or destroy (a limb or organ); to wound severely, inflict violent or disfiguring injury on.

22 This is the way in which the word is explained in the UBS Translators Handbook on Galatians (Arichea & Nida 1975:129). Similarly, in the UBS dictionary, the same happens;

is explained as follows: "mid. mutilate or castrate oneself". (Their emphasis.) The significance of the use of the middle voice in interpreted correctly by some commentators, for example, Schlier (1971:240), Mussner (1977:362), Bruce (1982:238) and Dunn (1995:282).

is explained as follows: "mid. mutilate or castrate oneself". (Their emphasis.) The significance of the use of the middle voice in interpreted correctly by some commentators, for example, Schlier (1971:240), Mussner (1977:362), Bruce (1982:238) and Dunn (1995:282). 23 See also Zerwick (2001 [1963]:75) and Winer-Moulton (1882:319).

BIBLE TRANSLATIONS CONSULTED (See footnote 19)

ASV: American Standard Version (1901).

BBE: The Bible in Basic English (1949/64).

DBY: The Darby Bible (1884/1890).

DRA: Douay-Rheims American Edition (1899).

ESV: English Standard Version (2001).

KJV: king James Version (1611/1769).

NAB: The New American Bible (1986).

NAS: New American Standard Bible with Codes (1977).

NIB: New International Version (1984) (BR).

NIV: New International Version (1984) (US).

NJB: New Jerusalem Bible (1985).

NkJ: New king James Version (1982).

NLT: New Living Translation (1996).

NRS: New Revised Standard Version (1989).

RSV: Revised Standard Version (1952).

RWB: Revised Webster Update (1995).

TEV: Today's English Version (1980).

WEB: Webster Bible (1833).

YLT: Young's Literal Translation (1862/1898).