Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Psychology in Society

On-line version ISSN 2309-8708

Print version ISSN 1015-6046

PINS n.63 Stellenbosch 2022

ARTICLES

Foregrounding ecojustice: A case study on trans-species accompaniment

Andrea Marais-PotgieterI; Alison FaradayII

IDepartment of Psychology, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa and the Noordhoek Environmental Action Group. andrea@plunge.co.za

IIToadNUTs and the Western Leopard Toad Conservation Committee. alison@leopardstone.co.za

ABSTRACT

A tsunami of development projects is sweeping across the planet. This includes another 25 million kilometres of new paved roads by 2050 - enough to encircle the globe more than 600 times. Approximately 90% of these new roads will be built in low- and middle-income countries that are likely to have high biodiversity. This paper focuses on the environmental impact of 1.2 km of road planned to be built through endangered western leopard toad habitat and breeding ponds and extending into a greater wetland system in Cape Town. This paper reports a case study of the experiences of two female community environmental activists (the authors) throughout the public participation process and environmental impact assessment for this road. The results show the contesting of power in public participatory spaces as a form of trans-species accompaniment, and the generation of emotive knowledge (including distress and a sense of betrayal). The paper contributes to the existing knowledge of the execution of trans-species accompaniment in the context of public participation processes to seek ecojustice.

Keywords: public participation process, trans-species activism, ecojustice, extinction, western leopard toad

Introduction

Globally, most ecosystems have been affected by human development (Kong et al., 2021). The Biodiversity and Climate Change report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2021) has highlighted maintaining biodiversity in the context of climate change risks, yet the City of Cape Town is leading the world in terms of species threatened with extinction or extinct (Rebelo, 2018). Thirteen plant species that once occurred in Cape Town are now globally extinct in the wild, and a further 307 plant and 27 animal species are in imminent danger of extinction (Rebelo, 2018). A quarter of Cape Town's frogs and toads are threatened with extinction with urbanisation being the largest threat (Rebelo, 2018). Roads place significant pressure on the survival of species (Alamgir et al, 2017). With these local environmental challenges, community activism during public participation processes has an important role to play in seeking ecojustice. However, participatory processes (Cooke & Kothari, 2001; Barnes, 2009) and environmental impact assessments (Bond et al., 2021) are riddled with problems.

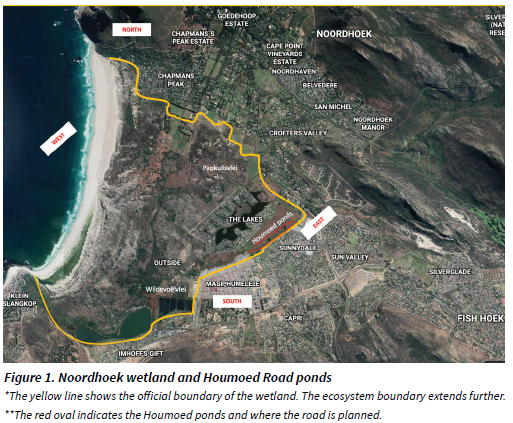

This case study centres on the experiences of two community-based environmental activists during an environmental impact assessment and public participation process for Houmoed Avenue Extension Phase One (hereafter Houmoed), which began in 2017. This 1.2 km road planned by the City of Cape Town (hereafter referred to as the City) will impact a wetland and three breeding ponds of the endangered western leopard toad (Sclerophrys pantherina). The application triggered the National Environmental Management Act, 1998. Houmoed falls partially within a road reserve proclaimed before the value of wetland ecosystems/biodiversity was understood, and long before the current urbanisation and densification pressures in the Noordhoek valley. The Noordhoek wetland has experienced "death by a thousand cuts", and this road stands to be the tipping point for its collapse and the gradual emptying out of the wetland fauna over time (W Harding, personal communication, 22 November, 2019).

Ecojustice and trans-species accompaniment

Ecojustice foregrounds violence against nature, unlike environmental justice that foregrounds how violence against nature impacts humans. Washington et al (2018) and Kopnina (2019) make compelling arguments for the foregrounding of ecojustice, because otherwise in cases where nature and humans are in conflict, nature will be discriminated against. They regard this widening of moral accountability as an important part of society's ethical progress, and as vital to avoid planetary collapse. Ecojustice prioritises concerns for the biosphere and species regardless of their value to humans (Schlosberg, 2004; 2007). Although this foregrounding can be interpreted as misanthropic, Washington et al (2018) argue that it is not, because no individual of any species can survive in isolation from conspecifics or other species. This line of reasoning falls squarely within the mainstay of systems thinking (Meadows, 2008), and ecojustice can in fact be seen to promote future social justice by safeguarding ecosystem services that are essential for society (especially the poor) (Washington, 2018; Fios, 2019). Non-human nature has the right to justice and should be acknowledged as sharing environmental resources with humans and requiring equal access to and use of such resources to live, survive, and thrive (Washington et al, 2018). Cullinan (2003) calls this view "earth jurisprudence", which maintains that nature (and species) has an existential right to exist.

There is an overlap between ecojustice (Cullinan, 2003; Schlosberg, 2004) and trans-species accompaniment as a form of liberation psychology (Watkins, 2019; Bradshaw, 2019). Trans-species accompaniment aims to shift dialogues from an anthropocentric focus towards a non-hierarchical, species-inclusive ontology where species "voices" are brought into public participation in search of participatory justice (Bradshaw, 2019). It aims for biospheric egalitarianism (Kopnina, 2014). Farmer (2013: 234) defines accompaniment in homocentric terms, but the authors propose an amendment to the definition to focus on trans-species accompaniment:

"To accompany other species is to go somewhere with them, to acknowledge their right to be free from oppression and exploitation on a journey with a beginning and an end. There is an element of mystery, of vulnerability, of bearing witness. The companion, the accompanier, says: 'I'll go with you and support you on your journey wherever it leads; I'll share your fate.' Accompaniment is about remaining a witness, whether it leads to extinction or protection." (The authors)

Washington et al (2018) call this "representation for nature" where non-human nature is guided and supported as stakeholders in democratic processes rather than objects. Species are seen to have the right to self-determination, mutual flourishment, right to be heard, and not be objectified (Cullinan, 2003). The aim is to ensure action against oppression for liberation by placing one's life alongside species for the common purpose of addressing injustice (Watkins, 2019). Accompaniment is to bear witness to the non-human causalities of colonialism.

"The practice of accompaniment is embodied, requiring that we move alongside those we are accompanying. At the same time, it draws from deep underground springs of radical imagination and spirituality that enable us to create needed commons. Where division, exclusion, and separation are causes of human misery, in practices of accompaniment we cross over the barriers that have been erected, drawing together what has been sundered." (Watkins, 2019: 48)

Psychology is increasingly integrating social justice issues with environmental concerns, such as climate change, into its discourse. Although there has been some exploration of psychology within a trans-species context (Watkins, 2013), there is a limited understanding of what this looks like in the context of activism and the public participation process during development applications in South African biodiversity hotspots. This case study aims to take the reader on a journey with two community activists (the authors, one from ToadNUTs and one from the Noordhoek Environmental Action Group) as they battle the City of Cape Town to protect the endangered western leopard toad from localised extinction.

Case Study

In 1997 the Cape Metropolitan Council drew up an integrated Noordhoek wetland management plan due to the unfavourable effects of increasing urban development on the delicate environment (Wilkinson, 1999). The wetland is currently managed by South African National Parks, although parts are owned by the City of Cape Town. These authorities have done little to protect this threatened ecosystem, and in 2004 the City of Cape Town made its first attempt to build Houmoed (Figure 1). However, authorisation for the road was set aside by the Ministry of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning in terms of Section 35(4) of the Environmental Conservation Act (Act 73 of 1989). The decision related to the process of public participation, need and desirability, adequacy of information, cumulative impact, and socio-economic impact. Since then, the wetland has been subjected to increased surrounding development pressure from the City of Cape Town's densification policy, unsophisticated poaching, illegal land occupation in the wet areas of the wetland and around one of the Houmoed ponds, invasive alien vegetation, man-made fires, and pollution, all of which have gradually diminished the wetland's functionality and biodiversity.

Growth-centred development prioritises economic growth over people and the biosphere (Van Vlaenderen, 2001). This myopic pattern can be observed within the City where the extent of development is directly proportional to eco-social justice issues (Bradshaw, 2019). The City has a reputation for brutal policies towards the poor in matters related to environmental justice (Green, 2020) as well as numerous environmental failings (Rebelo et al, 2011; Kretzmann, 2019; Olver, 2019; Centre for Environmental Rights, 2020; Green, 2020; Human, 2021). It has also been implicated in cases of corruption (Payne, 2021), painting a picture of a city with a questionable moral compass putting the survival of species at risk.

Since 2007, under the umbrella of the Western Leopard Toad Conservation Committee chaired by the South African National Biodiversity Institute, volunteers (including the ToadNUTs), have been actively saving toads from extinction, particularly during the winter migration period. The City of Cape Town sits on the Western Leopard Toad Conservation Committee as a representative, along with other organisations such as Cape Nature and Table Mountain National Park. Yet this committee was not approached by the environmental assessment practitioner for specialised comment during the public participation process for Houmoed.

The rapid decline in the number of endangered western leopard toads in the suburbs surrounding the wetland may be the "canary in the coalmine". The western leopard toad is classified on the IUCN database as "endangered in the wild" (Measey et al, 2019). This toad is an indispensable indicator species whose existence requires healthy freshwater and connected landscapes (Kruger, 2014). By conserving the western leopard toad, many other amphibians and food chains are protected. However, ToadNUTs recorded only 250 toads (18.8% dead) in Noordhoek in 2021, down from 676 toads (13.6% dead) in 2016. In the area where the road is proposed, no amphibian study has been done to quantify the western leopard toad population, but during the breeding season their calls can be heard from the ponds, and migrating individuals are rescued from surrounding suburban roads. The proposed road lies within their migratory route and breeding area, where satellite males will sit at a distance from the ponds in the path of the proposed road. The associated traffic noise (preventing the mating calls from being heard), water pollution (impacting the development of the toadlets), and roadkill is likely to severely impact this indicator species, leading to the disappearance of many other species of fauna and flora from this area. W Harding (personal communication, 22 November, 2019), a specialist in urban-impacted aquatic environments notes in his review about the application:

"The road effect will probably extend to the entire extent of the wetland, with the construction of the road resulting in the progressive loss of most biota from the wetland, biota whose presence and role in the wetland are currently completely unknown."

Houmoed will be constructed as a twenty-metre-wide road, designed to carry 1000 vehicles per hour at peak periods. This will be too dangerous for volunteers to navigate. Usually, the volunteers carry toads across roads during the migration, slow traffic at night, count dead and live toads, install toad savers in swimming pools, do education outreach, and participate in development applications. Kruger (2014) found that toad volunteers displayed passion (for the environment), emotional engagement, the achievement of purpose, thrill/excitement, and a sense of directly saving lives. Measey et al (2019) referred to this as "a powerful Citizen Science campaign" where volunteer organisations such as ToadNUTs mobilise residents to save an endangered species. However, saving a species includes the protection of breeding habitats and migratory routes. The threats to the survival of this and many other species include residential and commercial development, agriculture and aquaculture, invasive species, and roads. The combined pressures of habitat loss and climate change events such as droughts have led to broad-based population decline (Measey & Tolley, 2011), and this road is likely to push this species into localised extinction.

The activists had to learn to navigate the Houmoed public participation process over the years, often with assistance from experts. The activists had to read, analyse, summarise, prepare comments on, and evaluate thousands of pages of reports from experts on fauna, fresh water, traffic, and other aspects of the environment. Cumulatively, thousands of hours have been spent on these processes over the past five years (ongoing). This suggests a process that is inherently exclusionary and unfair, as very few people have the capacity to participate at this level. The process is a rigid procedure often shaped around the desired outcome and inherently anthropocentric (Bond et al, 2021). This process is the antithesis of what Cullinan (2003) calls the principle of "subsidiarity", which holds that decisions should be taken by the community that is most directly affected and most intimately concerned with the issue, unless there is a good reason not to. Because this approach is not followed in South Africa, vulnerable species fall through the cracks of environmental impact assessments (Simmonds et al, 2020) due to inadequate investment, insufficient scope, vested interests, and poor governance (Laurence et al, 2018). Environmental impact assessments are supposed to be the frontline of environmental protection when it comes to development. If the impact on nature includes anything the government has pledged to protect, such as endangered species, the development should technically be halted or redesigned to avoid the impact. But environmental impact assessments rarely prevent catastrophic projects in South Africa (Little, 2019).

The main human communities to be impacted by Houmoed include Masiphumelele, Lake Michelle, Milkwood Park (Sunnydale), Noordhoek, and Kommetjie. These communities are mainly fragmented due to inequality. Few people from the wealthier communities seem to venture into the wetland due to fear (snakes, crime, snares), lack of footpaths, and perhaps a lack of connection to wild nature (Sonti et al, 2020). Masiphumelele (formerly known as "Site Five") is situated in the south and has a high rate of HIV-positive and unemployed residents. Their dire circumstances have been brought to the attention of the SA Human Rights Commission and the Office of the Public Protector (Hoffman, 2021). An illegal extension of Masiphumelele comprises a community living in raised shacks among the wet reed beds of the wetland. The 2011 Census reported that 49% of the shacks in ward 69 (which includes Noordhoek and Masiphumelele) were headed by children under 18 years of age.

The activists found that the residents of Lake Michelle, a gated community built within the wetland during the 1980s, had a vested interest in their specific area but little concern for the broader wetland. Numerous attempts by the activists to engage them in efforts to protect the wetland and toads were ignored. Many residents of the middle-income suburb Milkwood Park (Sunnydale), on the southern edge of the wetland between the shopping malls and Masiphumelele, showed little connection to the wetland as it is not visible to most of them. There was some support for activism at the start of the process, but this dwindled over the years. This decline could be attributable to feelings of helplessness (Landry et al, 2018), compassion fatigue (Bride et al, 2007) and, more recently, fear of the cost of a High Court case against the City of Cape Town. Nevertheless, this community is likely to feel the greatest impact of the noise and air pollution from the road. Kommetjie, situated at the periphery of the wetland, is a high-income suburb that has seen high-end housing developments approved and experienced subsequent traffic issues. Kommetjie Road is still plagued by traffic jams despite its recent major upgrade and few Kommetjie residents supported the activists as most believed Houmoed would alleviate the traffic congestion. Noordhoek is a suburb with an equestrian subcommunity who use the wetland for horse riding, and is the location of the activist authors and the volunteer groups involved in this case study.

In February 2017, the activists received basic information about the planned Houmoed via e-mail (after registering as interested and affected parties). Four activists from three organisations, namely ToadNUTs, the Noordhoek Environmental Action Group, and the Milkwood Park Environmental Group, volunteered as interested and affected parties to represent the natural environment. Between 2017 and 2019 this process included the preparation and submission of a series of comments on the assessment reports, engagement with various communities, media releases and interviews, consultations with specialists, approaches to the authorities to undertake joint wetland and pond walks, and strategy workshops. On 22 November 2019, a notification was received by the Noordhoek Environmental Action Group that the competent authority (Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning) had granted environmental authorisation. An appeal against the environmental authorisation was lodged by ToadNUTs, the Noordhoek Environmental Action Group, and a group of residents on 29 January 2020 in terms of section 43(2) of the National Environmental Management Act, 1009 (Act no. 107 of 1998). The appeal was dismissed eight months later on 18 September 2020 by the Minister of Local Government, Environmental Affairs and Development Planning. The activists then began a new cycle of fundraising, media exposure and community communication, and appointed a legal team for a High Court case against the City and the Western Cape MEC for Local Government.

Methods

Study design

The study was a case study design (Miles, 2015), that drew on elements of participatory action research (Watkins & Shuman, 2008), community surveys (Coomes et al, 2020), observations (Anguera et al, 2018), and personal reflections (Schiffer, 2020). The case study aimed to position trans-species accompaniment as a process of contesting power (Miles, 2015).

Sample and sampling

For the community surveys, purposeful sampling was used to obtain information-rich cases with limited resources (Palinkas, 2015). Purposeful convenience sampling (Patton, 2002) was used for the paper and pencil survey of Masiphumelele residents. Interviewees were randomly approached in Masiphumelele and a sample of 34 was obtained. Purposeful criterion sampling (Patton, 2002) was used for car drivers who would potentially use the proposed road. Participants accessed the survey online through social community networks. A sample of 107 was obtained.

Procedure

There was an expectation during the application that the road would be a panacea for all social, environmental, and developmental issues. The surveys therefore aimed to explore these claims and assumptions and foreground the participatory injustice in our comments on the public participation reports. Participatory action research and community surveys were conducted during the public participation process. There was a need to include the missing voices of the communities that would be impacted (positively and/or negatively) by the development. First, the authors conducted the online survey to understand whether car drivers (N = 107), who stood to benefit from the road in the short term, had any environmental concerns regarding the development. The questionnaire items were determined by the activists based on a range of discussions and the perceived gaps identified in the environmental impact assessment reports. Participants were asked to agree or disagree with a range of statements (for example, the road will increase traffic / the same amount of traffic will be spread evenly / traffic lights will be needed to assist with flow) and were invited to explain their answers.

Second, a paper and pencil survey followed when the activists realised that the voices of Masiphumelele residents were largely missing. Participants (N = 34) were asked open-ended questions about whether they were aware of the proposed road, and what they thought and felt about it. The items were generated by the activists and their understandability was checked with the interviewers. The interviewers were Masiphumelele residents who worked as teachers at a school in Masiphumelele. They were able to translate the questions if necessary, during their interviews.

The case study observations and reflections in this manuscript emerged through a series of workshops with the legal team and the activists as sense was made of the experiences, encounters with power structures, and accompaniment in preparation for the High Court case.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics (Amrhein et al, 2019) in the form of percentages were used for the online survey data. Thematic analysis (Neuendorf, 2019) was used for the survey with residents in Masiphumelele and the qualitative reflections from the authors.

Positionality and reflexivity

Accompaniment with a decolonial agenda requires critical reflection on how we might be benefitting from our privilege at the expense of others. It encourages the questioning of assumptions and representations of self and other that may unintentionally reinforce the structures that cause suffering (Watkins, 2019). Reflecting examines how one might be personally implicated in the very conditions that allow for cross-species oppression and exploitation.

Author 1 states: I do not accept anthropocentric values as a necessary model for my own life and the activism I am involved in. My worldview shifted approximately 10 years ago when I became vegan as an illustration of human de-privileging and nonhuman valuation. I value conservation and ecojustice underpinned by biophilia, place attachment, and distress as a personal response to the sixth mass extinction. I embrace a conflict model, working with power struggles locally and within communities that is central to my volunteering. I acknowledge that there is a degree of power relations and bias in my work. I am reminded of the words of Mary Watkins (2019: 38): "When we stand by someone who is experiencing great difficulty, we necessarily bring in who we are as a person and what we know about the issues and conditions that have contributed to their suffering". I acknowledge my positionality in relation to the inequality inherent in the public participation process and how my privilege and education have allowed me to participate in these processes.

The following vignette describes an experience that inspired Author 1 to become involved in protecting the endangered western leopard toad, Noordhoek wetlands and join the Noordhoek Environmental Action Group:

"I was on one of my first toad patrols on a rainy winter night in Noordhoek. The toads were quiet on the main routes, so we decided to see if we could patrol in the eco-estate Lake Michelle, known to be a key breeding area during their migration. We had to use a lot of persuasion to get the security guard to allow us in. After a range of steps, we entered. It felt like driving through the aftermath of a bloody war. We counted one dead toad after another. At that moment it felt like extinction was happening right in front of me. As my heart started circling the shadow of my shame, I saw a toad that was still alive in the middle of the road. Suzie cautiously stopped an oncoming car so I could scoop up the toad and carry it to the other side towards safety. As I touched her cold beautiful body still filled with eggs, I noticed that she looked exhausted. Toads can travel kilometres to reach a breeding pond. But something was wrong. Her mouth was open, and I noticed some poison that had been excreted from her glands. At that moment I became aware of her dangling foot softly touching the side of my hand. She was in a liminal space between living and dying, and I was the witness. Her eyes were quickly losing their lustre. Another senseless death on a road in a heterotopian1 "eco-estate". As I watched her slip into unconsciousness, I felt partially responsible for her death, and I couldn't help but wonder how many animals I might have accidentally killed while driving my car."

Author 2 states: I live what many may consider to be a life of suburban privilege in the leafy suburb of Noordhoek. I experience the many conveniences of my location but I have attempted to remain mindful of the needs of the original inhabitants of this land - porcupines, toads, birds, and insects, all endemic to the Cape Coastal region. My garden is purposely planted with endemic plants -the starting point for creating feeding opportunities for many insects and birds. We have constructed an eco-pool in which endangered western leopard toads now breed. I give talks to school children about the plight of the western leopard toad. I ask them: "Who knows what extinct means?" and many small arms are raised. "I know, I know," they call eagerly. "It means gone forever." And my heart breaks. And then I tell them that we may not be able to save the rhino, but we can save the western leopard toad. I explain with passion what they can do to make their small suburban patch more toad friendly. And I hope that this new generation will not give up so easily. I will not give up easily. ToadNUTs was formed in 2007 to save the western leopard toad from extinction. We tell ourselves "this animal will not go extinct on our watch" and year after year we pledge our faithful commitment to this species, and hope to assist several other species along the way.

Findings

The findings describe the experience of contesting power in public participatory spaces as a form of trans-species accompaniment, and the generation of emotive knowledge as part of ecojustice.

The primary goal of the community activism was to contest power during the public participation process as a form of trans-species accompaniment. The activists sought to advocate for the right of the endangered western leopard toad to biological viability, and for the conservation of their breeding ponds and wetland habitat as the authorities did not fully consider the impact of the road on the toads. This shaped the interactions with the public participation process, authorities, and court papers. The activists repeatedly requested that a study of anuran amphibians, (the group to which the western leopard toad belongs) should be done as part of this process rather than after approval was granted, as recommended by the environmental assessment practitioner. Such a study would have provided the decision-makers with the necessary empirical information. The precautionary principle (Hickey & Walker, 1994) requires that if there is suspicion that a development activity will be detrimental to the natural environment, it should be abstained from rather than waiting for complete scientific proof of a risk. In other words, if there is uncertainty, the environment is given the benefit of the doubt. The environmental assessment practitioner chose not to conduct an amphibian study and to simply obtain a comment from an appointed anuran expert. This expert indicated hesitancy regarding the effectiveness of the proposed mitigation measures (mainly tunnels and barriers to direct toad movement), saying: "it would likely be fairly efficient at regulating the safe movements of western leopard toads in this area." No mitigation was proposed for the impact of noise which would impact breeding behaviour. The activists sought ecojustice through holding the authorities accountable for their lack of institutional consciousness and ethics. The activists advocated for a biocentric approach to development in biodiverse areas where endangered species are found, rather than treating citizens and species as passive receptors of imposed developments with public participation reduced to a tick box exercise rather than a consultative process. The authorities cited section 2(2) of the National Environmental Management Act as their guiding principle: "to place people and their needs at the forefront of its concern, and serve their physical, psychological, developmental, cultural and social interest equitably". In response, the activists pointed out that extinctions and environmental collapse will impact future generations, and therefore seeking ecological justice is aligned with section 2(2) of the National Environmental Management Act. Furthermore, the activists aimed to hold the City of Cape Town ethically accountable for appointing an environmental assessment practitioner who was also a director of the construction company awarded the contract for the Kommetjie Road upgrade, of which Houmoed would initially have been a temporary bypass road. The practitioner failed to declare this potential conflict of interest as was required in terms of regulation 13(1)(f) of the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulation, 2014, promulgated in terms of the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998.

The activists also aimed to address the participatory injustice. At first the notion of a public participation process gave the sense that citizens could contribute towards development decisions that would impact their lives, the natural environment, the sense of place, and future generations. However, the process served as a fagade for decision-making, as the public had no ability to exert social influence, political power, and ecojustice, or access the necessary resources to guide development towards biocentricity. The fagade was revealed when the environmental assessment practitioner and a City official told residents early in the participation process that "the road would go ahead" (confirmed in two supplementary affidavits), demonstrating public disempowerment (van Vlaenderen, 2001). This is just one example of participatory injustice where the desired development outcome was prioritised over its negative impacts on the wetlands, toads, residents of Masiphumelele (prioritising roads over the provision of basic services), Kommetjie residents (encouraging and justifying further development and increased traffic), and Noordhoek and Milkwood Park residents (quality of life, sense of place, extinction of toads, and loss of biodiversity).

The availability of resources was unequal in that the City had funds from residential taxes to employ a host of specialists with skills and time, whereas the activists had to fundraise to employ specialists; work after hours or on weekends; and were overwhelmed by the level of technicality involved. Once funding was secured from donations and fundraising events (school concerts, raffles, and cooking classes) it proved difficult to find specialists, most of whom were contractually employed by the City and therefore reluctant to assist. The authorities proceeded to dismiss the two specialists' reports and the comments of the activists. It was clear that this was not an equal process. For communities such as Masiphumelele, meaningful participation was impossible: thick technical documents had to be read, and procedural complexities such as the withdrawal of the application due to procedural issues made the process even more convoluted and challenging. The public participation process was intrinsically biased, unfair, and exclusionary.

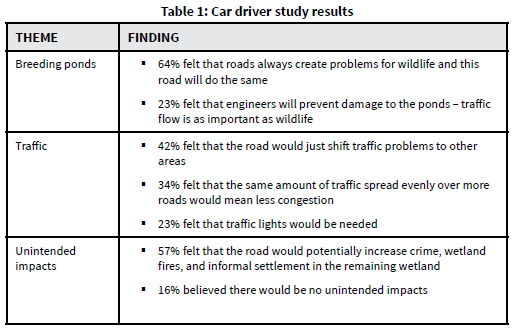

The contesting of power by the activists included inviting some of the unheard voices into the process. Leonard (2013) noted that historically, the exclusion of black people from land for conservation has shaped the relationship between people and the environment. Death (2014) suggested that concern for environmental issues relates to privileged white people who do not have to deal with extreme poverty. The activists felt that these voices were largely missing from the participation process and therefore conducted participatory action research to contest the power narratives. Those that participated in the online survey expressed a range of views. Some expressed biocentric values: "Disastrous. Wetlands are so important and are being reduced in size and this is another example of humans pushing their way into nature. It should not be allowed." Others expressed ambivalence as they struggled to prioritise the natural environment over their own challenges: "I am in two minds. On the one hand I want the wetlands to stay undisturbed and on the other hand I experience the traffic [congestion] on Kommetjie Road every morning and I do think the proposed road can [solve] a lot of problems." Those in favour of Houmoed believed it would solve the traffic problems or were confused about Houmoed Phase 2, which has different impacts and is not the subject of this paper: "It will alleviate a lot of traffic issues. The wetlands have already been built on with The Lakes developments." Table 1 presents the results from this study.

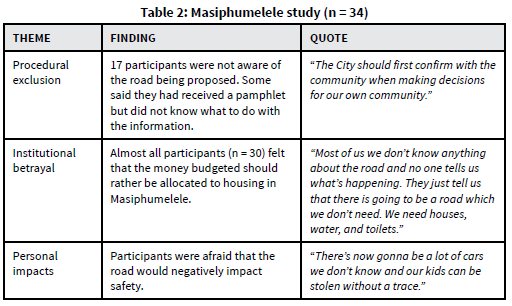

The activists speculated that the authorities were using Masiphumelele as a veiled reason to argue for the necessity and desirability of the road. The responding statement by the transport department acknowledged that several other available road reserves could be formalised to address traffic congestion, such as "opening up the left turn down Sunnydale Road off Kommetjie Road in order to bypass the four-way stop as an example." However, they said these would require the buy-in of the community (primarily white residents). It seemed clear that injustice towards toads, the wetland, and residents of Masiphumelele were lesser concerns. This pointed towards unequal rights and a biased view of desirability. Three main themes emerged (Table 2) from the survey with Masiphumelele residents: procedural exclusion; institutional betrayal; and personal impacts.

A sense of betrayal was shaped by the City of Cape Town and the environmental assessment practitioner who continuously used mitigation as a panacea for the development, creating a false sense of safety even though the road is diametrically opposed to micro-life and ecosystem health, putting biotic communities on the path to disruption and then extinction. The activists witnessed accelerated environmental degeneration caused by urban creep, environmentally damaging developments, the use of poisons, water pollution, and poaching in the wetland over the years.

The activists also experienced institutional betrayal as the ward councillor avoided direct involvement by telling them to "trust the process." The amphibian expert said that there was no point in the activists commissioning their own experts to contest power. When the activists persisted in employing their own experts, the views of these experts were indeed dismissed. Further attempts to silence the activists were made during their appeal against the environmental authorisation, where the mandate of the procedural expert employed by the activists was questioned, and the activists were instructed to obtain a mandate letter from each one of the approximately 200 individuals who had indicated their opposition to the road. This betrayal led to the experience of solastalgia from the awareness that this development is likely to be a tipping point for the species locally. Solastalgia is the distress produced by environmental change impacting on people (Albrecht, 2005, 2016; Clayton, 2020). The activists' experienced incongruous emotions ranging from hope (Macy & Brown, 2014), nature affiliation (Kellert & Wilson, 1993), universalism and benevolence (Schwartz, 2006), and sense of place (Knez et al, 2018), but the betrayal by the authorities had a negative psychological impact on the activists (Wallis & Loy, 2021) that lead to grief (Lertzman, 2015), and anxiety about ecological destruction (Landry et al, 2018).

Discussion

Efforts to protect species and ecosystems include the World Charter for Nature (adopted in 1982 by the United National World Commission on Environmental and Development), the 2010 Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth, the Bill of Rights Chapter Two of the South African Constitution (section 24, which recognises the right to protect the environment for the benefit of present and future generations), and institutions such as the Western Leopard Toad Conservation Committee. Unfortunately, these protocols had little impact in dealing with a development-centred city focused mainly on development for the privileged, and where endangered species fall through the cracks of environmental impact assessments (Simmonds et al, 2019) under the myth of human supremacy (Jensen, 2016). Little (2019), Senior Manager of Habitats at the Endangered Wildlife Trust, identified numerous weaknesses in environmental impact assessments, including a lack of procedural objectivity, lack of transparency in the selection of specialists and the inclusion of reports, inadequate peer review of specialist reports, lack of accounting for cumulative impacts, and corruption or collusion. It was in the face of these challenges that this paper described the activists accompanying the endangered western leopard toad through the public participation process of the environmental impact assessment for Houmoed, and the subsequent High Court case.

The case study demonstrated how animal accompaniment includes the foregrounding of already privileged humans and the recognition of the rights of animals and other living beings to self-determination (Bradshaw, 2019), including the right to water and a natural, noise-free habitat for biological viability. Accompaniment asks for participative biocentrism that acknowledges the interdependence of all life on earth (Watkins, 2019), while conceding that just by being human, activists too contribute to the demise of nature and the extinction of species. This emphasises how part of the accompaniment process implies engaging in critical self-reflection about the privileged position of humans regarding the ability to challenge systems of oppression in society (Washington et al, 2018). The case study highlighted how human privilege is responsible for putting pressure on the survival of other species. Houmoed, once built, would constitute slow, persistent violence against the western leopard toad, occurring mostly out of sight and leading towards a silent extinction. The case study further showed that ecojustice is inherently psychosocial because the damage suffered from environmental assaults is caused or exacerbated by inequities (Watkins, 2019). It confirmed that a society designed to promote the expansion of wealth is likely to exploit both other humans and the natural world (Fisher, 2013).

Nonhuman liberation and legal protection is needed for the survival of all species. According to Cullinan (2003: 175-176):

"Certain human interventions, such as consciously effecting radical alterations to Earth's climate, or destroying the habitat of another species to the extent that its extinction is inevitable, must not be capable of having legal legitimacy under human jurisprudence ... every human has a duty to resist practices that betray our most fundamental obligations to the Earth Community."

The activists aimed to challenge the anthropocentric interpretation of the public participation process and the National Environmental Management Act and questioned directives that aimed to dominate nature by treating nature and toads as objects to be managed rather than as living beings with rights. The case study explored injustice during the public participation process towards not only the toads but also the communities that would be impacted by the road. Participatory injustice was enabled through the weakening of environmental regulations, such as by convoluting the processes (e.g. withdrawing the application due to procedural issues, and then restarting it), and by the approval of ecologically injurious developments that are likely to cause the extinction of one or more species. Such tactics served to dilute environmental standards by discouraging public participation in the process (Leonard, 2018).

This case study contributed to existing knowledge by demonstrating trans-species accompaniment (Watkins, 2013) during public participation. It aimed to expand the understanding of trans-species accompaniment and liberation psychology to include amphibians and different ways to walk with them. The activists who literally walked with the toads across busy roads towards their breeding ponds, chose also to accompany them through a legal process by contesting power to avoid their extinction. The case study further contributed to the literature on how instruments such as the public participation process and environmental impact assessments undermine activism and seek to entrench the power of those already in institutional authority rather than enable true participation. It demonstrated that eco-distress is related not only to possible loss but also to a sense of institutional betrayal and participatory injustice, as experienced by the authors during the public participation process. The case study further showed how ecojustice can be foregrounded during the public participation process where internalised dominance over marginalised groups and species can be questioned. The process described activism to challenge the perpetual oppression of nature by humans. The case study also demonstrated accompaniment as an attempt to close the distance between the decision-makers and the human and ecological communities affected by their decisions. The activists attempted to restore the moral accountability that the layers of bureaucracy had obstructed.

Consideration of methodological limitations are required. A major critique of the case study method is that it is not suitable for generalisation (Stake, 1978). Although this case study might not represent a universal reflection, it aimed to further our understanding of the role of community activism in South Africa, and based on the identified enablers, barriers, and enactments, to provide a foundation for understanding the impact of environmental impact assessments. Furthermore, the participatory action research undertaken by the activists had several shortcomings. Due to limited time and funds available, the samples were too small to draw statistical conclusions. The main impediments to participation by Masiphumelele residents were that they had never heard of the proposed development or had other challenges to deal with. On reflection, the questionnaires could have been more exploratory and robust. Ethical challenges (Löfman et al, 2004) included the location of "power" where the activists owned the research and the participants were not necessarily invited to be part of the process from the beginning to the end to ensure an equal balance of power between the participants and activists.

Future research could explore the psychological impacts on activists when challenging power structures. It would also be beneficial to get a broader understanding of trans-species accompaniment such as the attempts to save chameleons in Knysna from development (Oosthuizen, 2018).

Conclusion

To date the activists have undertaken fundraising and spent around R850 000 fighting the development of Houmoed. The grounds for the High Court judicial review include the compromised objectivity of the environmental assessment practitioner, failure to obtain a specialist anuran study, procedural complaints, failure to apply the precautionary principle, and failure to consider the cumulative impacts on the wetland. The case study demonstrated that accompaniment is likely to be a long, dedicated and stressful process. In this instance, it could lead to either the survival or the extinction of the endangered western leopard toad.

"Scraping topsoil, plants and the rich community of life off land and covering it with concrete is also an assault on our inner world. If we continue too long on this course our consciousness, and those of the generations who follow us, will no longer be shaped through interaction with the beauty, diversity, and sheer unexpectedness, of nature. Concrete parking lots breed parking lot minds - uniform, barren, predictable and devoid of any sacred or transcendental meaning. How many great works of art or literature do you suppose our parking lots will inspire? How many laws on our statute books are inspired by this outlook?" (Cullinan, 2003: 190).

References

Alamgir, M, Campbell, M J, Sloan, S, Goosem, M, Clements, G R, Mahmoud, M I & Laurance, W F (2017) Economic, socio-political and environmental risks of road development in the tropics. Current Biology, 27(20), R1130-R1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.067 [ Links ]

Albrecht, G A (2005) Solastalgia: A new concept in human health and identity. Philosophy Activism Nature, 3, 44-59. [ Links ]

Albrecht, G A (2016) Exiting the anthropocene and entering the symbiocene. Minding Nature, 9(2), 12-16. [ Links ]

Amrhein, V, Trafimow, D & Greenland, S (2019) Inferential statistics as descriptive statistics: There is no replication crisis if we don't expect replication. The American Statistician, 73(1), 262-270. [ Links ]

Anguera, M T, Portell, M, Chacon-Moscoso, S & Sanduvete-Chaves, S (2018) Indirect observation in everyday contexts: Concepts and methodological guidelines within a mixed methods framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00013 [ Links ]

Barnes, B (2009) Community 'participation', resistance and water wars. Journal of Health Management, 11(1), 157-166. [ Links ]

Bond, A, Pope, J, Morrison-Saunders, A & Retief, F (2021) Taking an environmental ethics perspective to understand what we should expect from EIA in terms of biodiversity protection. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 86, 106508. [ Links ]

Bradshaw, G A (2019) Nonhuman animal accompaniment, In Watkins, M (ed) (2019) Mutual accompaniment and the creation of the commons. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Bride, B E, Radey M & Figley C R (2007) Measuring compassion fatigue. Clinical Social Work, 35(3), 155-163. [ Links ]

Centre for Environmental Rights (Feb, 2020) Philippi Horticultural Area Food and Farming Campaign & Others v MEC for Local Government, Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Western Cape. https://cer.org.za/virtual-library/judgments/high-courts/philippi-horticultural-area-food-farming-campaign-others-v-mec-for-local-government-environmental-affairs-and-development-planning-western-cape [ Links ]

Cooke, B & Kothari, U (2001) Participation: The new tyranny? London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Coomes, O T, Takasaki, Y & Abizaid, C (2020) Impoverishment of local wild resources in western Amazonia: a large-scale community survey of local ecological knowledge. Environmental Research Letters, 15(7), 074016. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab83ad [ Links ]

Clayton, S (2020) Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74, 102263. doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.102263 [ Links ]

Cullinan, C (2003) Wild law: A manifesto for earth justice. Cambridge, England: Green Books. [ Links ]

Death, C (2014) Environmental movements, climate change and consumption in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 40(6), 1215-1234. [ Links ]

Farmer, P (2013) To repair the world: Paul Farmer speaks to the next generation. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Fios, F (2019) Building awareness of eco-centrism to protect the environment. Journal of Physics, 1402(2), 022095. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1402/2/022095. [ Links ]

Fisher, A. (2013) Radical ecopsychology: Psychology in the service of life. New York, NY: Suny Press. [ Links ]

Green, L (2020) Rock, water, life: Ecology & humanities for a decolonial South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Hickey, J & Walker, V R (1994) Refining the precautionary principle in international environmental law. Virginia Environmental Law Journal, 14(3), 423-454. [ Links ]

Hoffman, P (2021) The inconvenient truth about Masiphumelele. https://www.news24.com/news24/columnists/guestcolumn/paul-hoffman-the-inconvenient-truth-about-masiphumelele-20210223 [ Links ]

Hook, D W & Vrdoljak, M (2001) Fear and loathing in northern Johannesburg: The security park as heterotopia. Psychology in Society, 27, 61-83. [ Links ]

Human, L (2021) New data shows how badly polluted Cape Town's vleis are. https://www.groundup.org.za/article/zandvlei-opens-boating-after-sewage-scare/ [ Links ]

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2021) Climate Change 2021: The physical science basis. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCCAR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf [ Links ]

Jensen, D (2016) The myth of human supremacy. New York: Seven Stories Press. [ Links ]

Kellert, S R & Wilson, E O (1993) The biophilia hypothesis. Washington, DC: Island Press. [ Links ]

Knez, I, Butler, Ä, Sang, Ä O, Angman, E, Sarlöv-Herlin, I & Äkerskog, A (2018) Before and after a natural disaster: Disruption in emotion component of place-identity and wellbeing. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 55, 11-17. [ Links ]

Kong, X, Zhou, Z & Jiao, L (2021) Hotspots of land-use change in global biodiversity hotspots. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 174, 105770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105770 [ Links ]

Kopnina, H (2014) Environmental justice and biospheric egalitarianism: reflecting on a normative-philosophical view of human-nature relationship. Earth Perspectives, 1(1), 1-11. [ Links ]

Kopnina, H (2019) Anthropocentrism: Practical remedies needed. Animal Sentience, 3(23), 37. Doi/10.51291/2377-7478.1392 [ Links ]

Kretzmann, S (2019) Cape Town's rivers are open streams of sewage, yet the city is not spending its budget. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-09-26-cape-towns-rivers-are-open-streams-of-sewage-yet-the-city-is-not-spending-its-budget/ [ Links ]

Kruger, D J D (2014) Frogs about town: Aspects of the ecology and conservation of frogs in urban habitats of South Africa. Unpublished doctoral thesis. North-West University. [ Links ]

Landry, N, Gifford, R, Milfont, T L, Weeks, A & Arnocky, S (2018) Learned helplessness moderates the relationship between environmental concern and behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 55, 18-22. [ Links ]

Laurence, W, Cook, J & Salt, D (Dec, 2018) Environmental impact assessment aren't protecting the environment. https://ensia.com/voices/environmental-impact-assessment/ [ Links ]

Leonard, L (2018) Bridging social and environmental risks: the potential for an emerging environmental justice framework in South Africa. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 36(1), 23-38. [ Links ]

Leonard, L (2013) The relationship between conservation agenda and environmental justice in post-apartheid South Africa: An analysis of Wessa KwaZulu-Natal and environmental justice advocates. Southern African Review of Sociology, 44(3), 2-21. [ Links ]

Lertzman, R (2015) Environmental melancholia: Psychoanalytic dimensions of engagement. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Little, I. (Sept, 2019) Environmental impact assessments are not saving our wildlife and wild spaces. Endangered Wildlife Trust. https://www.ewt.org.za/sp-sept-2019-environmental-impact-assessments-are-not-saving-our-wildlife-and-wild-places/. [ Links ]

Löfman, P, Pelkonen, M & Pietilä, A M (2004) Ethical issues in participatory action research. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 18(3), 333-40. [ Links ]

Macy, J & Brown, M (2014) Coming back to life. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers. [ Links ]

Meadows, D H (2008) Thinking in systems: A primer. London: Earthscan. [ Links ]

Measey, G J, Tarrant, J, Rebelo, A, Turner, A, Du Preez, L, Mokhatla, M & Conradie, W (2019) Has strategic planning made a difference to amphibian conservation research in South Africa? Bothalia-African Biodiversity & Conservation, 49(1), 1-13. [ Links ]

Measey, G J & Tolley, K A (2011) Investigating the cause of the disjunct distribution of Amietophrynus pantherinus, the endangered South African western leopard toad. Conservation Genetics, 12(1), 61-70. [ Links ]

Miles, R (2015) Complexity, representation and practice: Case study as method and methodology. Issues in Educational Research, 25(3), 309-318. [ Links ]

Neuendorf, K A (2019) Content analysis and thematic analysis. In P. Brough (Ed), Advanced research methods for applied psychology: Design, analysis and reporting. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Olver, C (2019) A house divided: The feud that took Cape Town to the brink. South Africa: Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen, N (2018) Breeding project to save the Knysna dwarf chameleon. Africa Geographic. https://africageographic.com/stories/breeding-project-save-knysna-dwarf-chameleon/. [ Links ]

Palinkas, L A, Horwitz, S M, Green, C A, Wisdown, J P, Duan, N & Hoagwood, K (2015) Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533-544. [ Links ]

Patton, M Q (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Payne, S (Sept, 2021) Sparks fly in provincial legislature in wake of report over alleged corruption by City of Cape Town. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-09-03-sparks-fly-in-provincial-legislature-in-wake-of-report-over-alleged-corruption-by-city-of-cape-town/. [ Links ]

Rebelo, A G, Holmes, P M, Dorse, C & Wood, J (2011) Impacts of urbanization in a biodiversity hotspot: Conservation challenges in Metropolitan Cape Town. South African Journal of Botany, 77(1), 20-35. [ Links ]

Rebelo, A G (2018) Extinct and threatened in Cape Town. iNaturalist: https://www.inaturalist.org/posts/17071-extinct-and-threatened-in-cape-town#summary. [ Links ]

Schiffer A (2020) Issues of power and representation: Adapting positionality and reflexivity in community-based design. International Journal of Art & Design, 39(2), 418-429. [ Links ]

Schlosberg D (2004) Reconceiving environmental justice: Global movements and political theories. Environmental Politics, 13(3), 517-540. [ Links ]

Schlosberg D (2007) Defining environmental justice: Theories, movements, and nature. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Schwartz, S H (2006) Basic human values: Theory, measurement, and applications. Revue Francaise de Sociologie, 47(4), 929. [ Links ]

Simmonds, J S, Reside, A E, Stone, Z, Walsh, J C, Ward, M S & Maron, M (2020) Vulnerable species and ecosystems are falling through the cracks of environmental impact assessments. Conservation Letters, 13(3), e12694. doi.org/10.1111/conl.12694 [ Links ]

Sonti, N F, Campbell, L K, Svendsen, E S, Johnson, M L & Auyeung, D S N (2020) Fear and fascination: Use and perceptions of New York City's forests, wetlands, and landscaped park areas. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 49, 126601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126601 [ Links ]

Stake, R E (1978) The case study method in social inquiry. Educational Researcher, 7(2), 5-8. [ Links ]

Van Vlaenderen, H (2001) Psychology in developing countries: People-centered development and local knowledge. Psychology in Society, 27, 88-108. [ Links ]

Wallis, H & Loy, L S (2021) What drives pro-environmental activism of young people? As survey study on the Friday For Future movement. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 74, 101581. [ Links ]

Washington, H, Chapron, G, Kopnina H, Curry, P, Gray, J & Piccolo, J J (2018) Foregrounding ecojustice in conservation. Biological Conservation, 228, 367-374. [ Links ]

Watkins, M (July 13, 2013) Accompaniment: Psychosocial, environmental, trans-species, earth. Presented at the Conference of Psychologists for Social Responsibility, Washington, DC. https://mary-watkins.net/library/Accompaniment-Psychosocial-Environmental-Trans-Species-Earth.pdf. [ Links ]

Watkins, M (2019) Mutual accompaniment and the creation of the commons. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Watkins, M & Shulman, H (2008) Toward psychologies of liberation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Wilkinson, K F D (April, 1999) Noordhoek Wetlands Management Plan. Cape Metropolitan Council: Catchment Management Department. [ Links ]

1 Heterotopia is a term first used by Michel Foucault (1966-1967) to describe worlds within worlds. For a good understanding of how this can be seen in South Africa, refer to Hook, D & Vrdoljak, M (2001 Fear and loathing in northern Johannesburg: The security park as heterotopia.