Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Psychology in Society

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8708

versión impresa ISSN 1015-6046

PINS no.56 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8708/2018/n56a4

ARTICLES

Long walk to semi-freedom: Towards a framework for psychological research on being out on bail

Khonzi Mbatha; Martin Terre Blanche

Department of Psychology. University of South Africa. Pretoria. mbathk@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

An important focus for psychological and other research on the criminal justice system concerns people who have been charged and are awaiting trial. However, most of this research has thus far focussed on remand detainees, who make up almost a third of the South African prison population. In this article we focus instead on those who are not in detention, but out on bail. Given the dearth of psychological research on bail we present a framework for researching the bail experience, incorporating both individual and community psychology perspectives. We identify five key elements in how individuals may experience being out on bail, namely, relief, uncertainty, identity issues, struggles related to belief in a just world, and being compelled to tell a "thin story". Each of these elements is associated with particular possibilities for future research. From a community psychological perspective, we identify two key characteristics of the "bail community", namely that it is firstly a 'community of disconnection' and secondly a "community of transience" - each of which, again, provides important research opportunities. It is our hope that this model will aid in directing and framing future research on the psychology of bail.

Keywords: awaiting trial, bail, community psychology, criminal justice system, pre-trial detention, prisons

Perhaps the key event in 20th century South African history was the tragic, but ultimately heroic, 27-year long incarceration of Nelson Mandela. Mandela's life story (Mandela, 1995) epitomizes the conventional idea of incarceration - being locked away in prison for a long time before being released to resume a normal life. In reality, for Mandela and for most of those who become entangled in the criminal justice system, life consists of a much more convoluted series of episodes of freedom, incarceration and semi-freedom. Mandela, for example, initially endured a series of detentions interspersed with periods of being out on bail, being released on a suspended sentence, being underground, and so on, before finally being incarcerated in Robben Island. Toward the end of his incarceration the nature of his detention again became complex as he was increasingly granted a type of pseudo-freedom within the confines of Victor Verster prison (Limb, 2008).

In this article, we explore the intricacies of one of the most controversial way-stations in many individuals' encounters with the criminal justice system, namely that of awaiting trial. The injustice starts at the very beginning of this process when bail decisions are made in ways (as we detail below) that discriminate against those without the financial means to establish their bail-worthiness to the satisfaction of the court. This includes issues such as not having the means to contact friends and relatives, not having what is deemed a stable residential address, and not having access to private legal representation. The effect of any one of these issues may not be profound - for example, Karth (2008) found that in three South African courts she studied, those with private representation were only slightly more likely to be granted bail - but cumulatively the effect of these factors can be seen in a clear correlation between financial means and likelihood of being granted bail (Rabuy & Kopf, 2016). As Chaskalson and de Jong (2009) point out, in South Africa many accused individuals are unable to afford bail, even when it is set to under R1 000. For those who are not granted bail, even more flagrant injustices occur as they are incarcerated for unconscionably long periods under inhumane conditions. As a consequence of the systemic miscarriages of justice associated with bail decisions and remand detention, a considerable amount of research attention and activism has been directed to these two issues. In this article we focus on a different pathway, that of actually being granted bail, which, on the face of it, would appear to be a purely positive outcome, but which we show to nevertheless be worthy of much more careful research scrutiny.

We pay particular attention to the psychological aspects of bail - both at an individual and at a community level. The purpose of the article is not to report on a study involving people out on bail, nor to provide a general theoretical model of what bail entails, but rather to provide a conceptual framework within which psychologically oriented research on bail can be conducted. Our intention is in this way to set a research agenda that will help to address the dearth of psychological research on bail and ensure greater synergy among different research projects.

Even though there is a considerable body of international research on bail - for a recent overview see the special issue on bail of the journal Issues in Criminal Justice (Hucklesby & Sarre, 2009) - the specifically psychological aspects of bail remain under explored. Much research has been done on the psychological impact of imprisonment (e.g., Schnittker & John, 2007) and, even more so, on how to predict recidivism (e.g., the role of gender in bail decisions, as outlined by Schumann, 2013) and how to provide the necessary psychological support to encourage rehabilitation - e.g. Lipsey and Cullen's (2007) systematic review of studies on the effectiveness of correctional rehabilitation. However, we have not been able to locate any similar research on bail.

It is generally agreed that bail is a positive element in the criminal justice process. There are a few reasons for this. One key reason is that the availability of bail furthers the ends of justice by putting into practice the idea that an individual who has not (yet) been found guilty of a crime should not be subjected to any form of punishment. As the White Paper on Remand Detention (2014) puts it: "This demonstrates the cardinal principle of the criminal justice process - that an accused person (whether detained or on bail) is presumed innocent until proved guilty" (2014: 23). Neither pre-trial incarceration nor being out on bail is overtly intended as punishment, but in effect both do involve some degree of suffering, with bail clearly providing a closer approximation to the ideal that no punishment should be meted out to persons who have not been found guilty.

In South Africa, in 2013 there were 45 730 remand detainees (Department of Correctional Services Annual Report 2012/2013, 2013), which was 30,4% of the total inmate population of 150 608. This number has scarcely improved since then (DCS Annual Report 2013/2014, 2014; DCS Annual Performance Plan 2014/2015, 2014). Although much is being done to improve the situation, such as the development of various protocols to streamline the bail and remand detention process (White Paper on Remand Detention, 2014: cf 11), it remains a gross human rights violation that almost 1 in 3 prisoners in South Africa are innocent (at least in the sense of not yet having been convicted of a crime). To further compound this, research has shown that accused persons who are on remand (rather than out on bail) are more likely to plead guilty and are more likely to be given a harsh sentence when they do go on trial (Allan et al, 2005; Sacks & Ackerman, 2015).

A second reason why bail is positively regarded concerns purely humanitarian issues. Despite ongoing efforts via the Department of Correctional Services capital works programme to upgrade and extend correctional facilities (White Paper on Remand Detention, 2014), many South African prisons remain relatively inhumane and overcrowded environments, as is repeatedly acknowledged by DCS, including in the Minister of Justice and Correctional Services' Budget Vote Speech in parliament (Masutha, 2014). Being at home rather than in detention, even if living under the threat of an impending court case, is clearly more humane than being confined to a harsh prison environment.

Remand detention also plays havoc with a person's familial duties, including in many cases the ability to earn an income (as described in detail by Schönteich, 2015). The potential humanitarian benefits of bail for accused persons and their dependents have to be weighed up against the interests of victims (who may be further victimised by a person who is out on bail) and the risk of flight. Granting bail is a delicate balancing act (Chaskalson & De Jong, 2009) as articulated in the classic sociological distinction between the interests of "crime control" versus "due process" (Packer, 1968). It is therefore no wonder that there is a voluminous literature on predicting bail outcomes (cf., Cadigan & Johnson, 2012) in an effort to ensure that the balance struck between these two imperatives are based on empirical grounds.

A final reason why bail is considered desirable concerns the financial impact on the national fiscus. The current cost per inmate is R9 876 per month, whereas electronic monitoring costs only R3 379 per month (DCS Annual Report 2012/2013, 2013). The cost to the Department of Correctional Services for persons who are out on bail with no electronic monitoring is nil.

Bail as a part of the criminal justice process

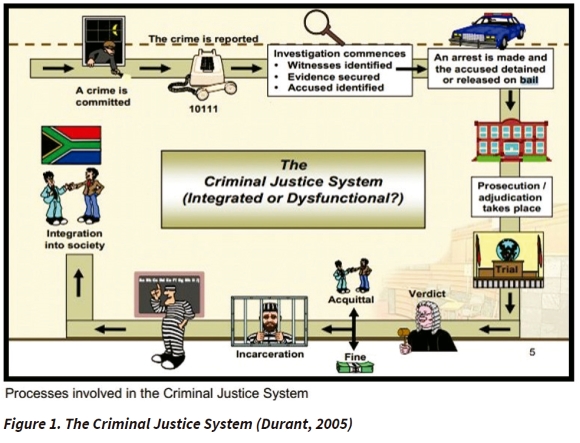

Key to understanding both the individual and the community psychological aspects of bail, is to view it in the context of the larger criminal justice process. Figure 1 shows a depiction of the process as visualised by Durant (2005).

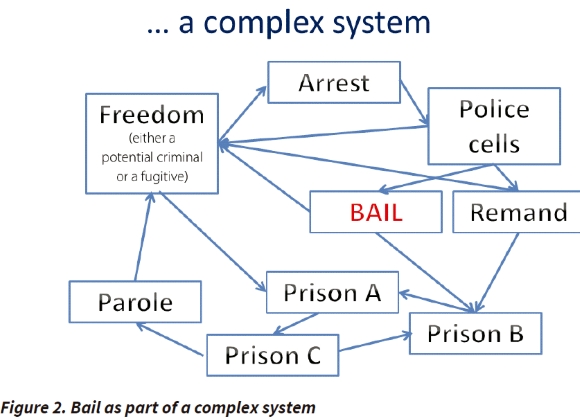

The process as shown in Figure 1 is linear, with a single entry-point (committing a crime) and only two possible exit points (either being acquitted or being released after serving a sentence). The depiction even comes complete with a "happy ending" in the form of being reintegrated into the "rainbow nation". In reality, of course, the process is often far more convoluted, with multiple entry and exit points, looping back on itself and not infrequently tracing a seemingly endless cycle of recidivism. Figure 2 is our own perhaps somewhat more accurate but no doubt still over-simplified representation of some of the possible pathways through the system. It should be evident from the figure that the process is far from linear and in fact resembles a complex, tangled web of possible routes into and out of incarceration. For example, it is common for incarcerated individuals to be moved from high to medium security sections of a prison after some years of "good behaviour" and to be moved between various prisons for logistical or other reasons. Typically, eventual release comes in the form of parole rather than outright freedom, and not uncommonly individuals are then re-incarcerated for parole violations. It is the kind of messy image shown in Figure 2 that one should bring to mind when thinking about the criminal justice system, rather than the sanitised version shown in Figure 1.

Crucial to note about the process is that it is a) complex, and b) circular (at least in some cases). Unlike the conventional image of imprisonment, there is no clean break between being caught up in the system and being completely separated from it. In this more cynical depiction, even "ordinary" life becomes entangled in the process in the sense that a person who is not (currently) incarcerated can be assumed to be a fugitive from justice or at the very least a potential criminal. This system (from which there is ultimately no escape) has been labelled a "carceral archipelago" (Foucault, 1977).

In Foucault's (1977) conception, modern societies do not primarily effect discipline by means of overt coercion. Instead there is a pervasive system of observation and evaluation of individuals, who soon learn always to act as if they were under scrutiny, even when not. The central disciplinary mechanism of modernity is therefore the individual himself or herself, but each of us is aided in this task of self-discipline by an array of institutions through which we migrate across a lifetime - family, school, clinic, hospital, courtroom, workplace, prison, halfway house, old age home. Some of these institutions, such as prisons, do have overt coercive aspects, but even in these, individuals exist under a constant regime of being watched and of having to keep an eye on themselves, a relentless imperative to reform, rehabilitate, become the best that they can be.

For those who are caught up in the criminal justice system, the movement from island to island in the carceral archipelago often takes a physical-spatial form, as they move between different sections of a prison (typically depending on how closely they manage to stick to the prescribed path of rehabilitation), between different prisons and between home and prison. However, the islands that individuals migrate between can also be more metaphorical, in the form of different social and legal environments that they encounter as they negotiate their identity as, for example, an accused person, a defendant in court, an offender, a gang member, an ex-offender, a re-offender, and so on. In the following section we describe the psychological implications of one of the way-stations that many of those who have become, or are about to become, nomadic within this archipelago encounter. We do not unpack Foucaultian ideas on discipline and punishment further here, but note that they can provide fertile theoretical grounding for the various different types of research on bail that we set out below.

Research opportunities on the individual psychology of being out on bail

There is a substantial literature on issues related to bail, for the most part focusing on bail decision-making and predicting bail outcomes (Karth, 2008; Bechtel et al, 2011; Mamalian, 2011; Sherrin, 2012). Omar (2016) provides a recent overview of psychological and other factors that affect court decisions about granting bail in the South African context.

However, we have been unable to find any literature that speaks directly to the psychological experience of being on bail. Literature (see Moller, 2005, for pointers to relevant South African research) exists on the experiences of the victims of crime and how they might be helped but, perhaps understandably so, suspected perpetrators of crime have been accorded a far less empathetic reception in the academic literature. As far as we have been able to ascertain, none of the work on the experience of accused persons focus specifically on the bail experience.

Given this dearth of research, we here provide a conceptual framework for possible future empirical studies on the bail experience. We hope that this framework will provide a means of directing researchers to which elements of the psychology of bail to focus on and to visualise how their work might relate to other similar studies.

We identify five main features to how bail might impact psychologically on individuals:

First, one can assume that in most cases, being granted bail comes as a relief - a sense of having, at least temporarily, escaped the sword hanging over one's head, and being able to resume a somewhat normal life. There is much scope here for studies drawing on concepts relating to the psychology of relief, especially what has been termed "temporal relief" (Hoerl, 2015).

Second, the subjective experience of being on bail can be assumed, in most cases, to be conditioned by a contrasting emotion, namely a pervasive sense of uncertainty. What will the outcome of the legal process be and when will there be an outcome? In many cases, especially in an overstretched system such as in South Africa, there are unconscionably long delays before cases are finally resolved (Leggett, 2005). In addition, there are uncertainties regarding pragmatic concerns, such as how much trust to place in the advice of legal counsel (Silver, 1999), and how to cover the costs involved. How those out on bail deal with these uncertainties provides rich opportunities for research.

It is probable that individuals typically have mixed feelings about being granted bail (relief and anxiety), which may in some cases manifest as an emotional roller-coaster. Tracking the emotional highs and lows, and how people manage them, could therefore be an important focus for psychological research on bail.

Third, being on bail may have a more profound psychological impact than merely eliciting contradictory emotions. Potentially, being on bail can confront a person with the possibility of having their very identity challenged. Those who have never been "in trouble with the law" may find their taken-for-granted identity as a stable and law-abiding person unexpectedly undermined, and even those who have a history of entanglement with the criminal justice system may start wondering if they are now about to become, in their own eyes and in the eyes of others, a "career criminal". Identity issues are pertinent to persons at various other stages in their encounter with the criminal justice system (such as being arrested, being in remand detention, being found guilty, and so on), and research relating to this in the context of bail could be particularly useful as it represents an early stage in the disruption of a person's previous identity as, for example, a law-abiding citizen, a "family man", and so on.

The challenge to identity also goes beyond one's relationship with the police, the courts and the prisons. More fundamentally, the period of being on bail may force many accused persons to consider the matter of their own guilt. This is not only in relation to the particular crime that they have been accused of, but whether they should think of themselves as the type of person who might justly be accused of such a crime - in other words how they should take on the identity of somebody who is a suspect and a formally charged person. Should they, for example, feel remorse, or justifiable anger at being falsely accused (Menard & Pollock, 2014)?

A fourth profound issue that some of those who are out on bail might confront is a challenge to their belief in a "just world" (Lerner & Montada, 1998). Much research has been done on how trauma can rock victims' belief in their community, their country and the world in general as a place where people "get what they deserve". If an accused individual considers themselves to be innocent, this may be experienced as a very personal and intimate assault on their previous belief that only bad people get into trouble with the law. Although it may be counter-intuitive to think of those who are out on bail as traumatised victims, it is likely that for many their experience is analogous to that of trauma victims - irrespective of their actual degree of guilt. We have not been able to locate any studies on trauma symptoms such as denial, difficulty concentrating, mood swings, withdrawal and hopelessness.

Fifth, one should consider the likelihood that the various psychological struggles and traumas described above may not overtly manifest in interactions with others, but may be covered over by the even more fundamental trauma of being compelled to tell a "thin story" (Pardo & Allen, 2008). Narrative theories and approaches to research may be particularly useful here (cf., Adshead, 2011). The criminal justice system is not in the first place interested in the accused as a rounded psychological being, with all the ambiguities and vacillations that that entails, but wants to fit his or her motivations and actions into clear-cut legal categories of innocence and guilt. Even friends and family probably do not want to know how the person feels about what has happened, but want to be reassured by a simple and plausible narrative that positions the person as unequivocally innocent or guilty.

Towards a community psychology approach to research on bail

As a sub-discipline of Psychology, Community Psychology seeks to shift the focus from intrapsychic phenomena to the psychology of collective experience. Typically, Community Psychological studies are concerned with how individual subjectivities are shaped by and give shape to geographical, cultural or other communities. As such, the degree to which a "sense of community" or "social capital" is present in a group of individuals is often the focus of research, with some evidence that economic progress has, in many settings, resulted in a weakening of this communal sense and a rise in psychological problems (Bowden, 1999; Glaeser et al, 2002; Putman, 2013).

Seen from this perspective, it is immediately evident that the "community of people who are out on bail" is far removed from the cohesive and coherent "ideal community" implicit in studies about sense of community. It is precisely for this reason that a Community Psychological perspective could be useful in understanding the psychological nature of bail - drawing attention to the special difficulties those who are out on bail experience, not only as individuals but as a non-cohesive group.

We suggest two ways in which the bail community's divergence from an imagined ideal community could be understood. Firstly, as "community of disconnection" and secondly as a "community of transience".

A community of disconnection

When individuals are arrested and then released on bail, their relationship and position within their communities are inevitably disturbed, for example by being regarded with suspicion or pitied by family members and friends or being shunned by work colleagues. At the same time, they also start to connect to other communities and networks, such as the legal fraternity, where they occupy a role (i.e., that of legal client) that may not have been part of their repertoire up to that point. What is most striking, however, is that people who are out on bail are typically radically disconnected from those who are concurrently sharing the bail experience with them. People who are out on bail are so for very different reasons and come from many different backgrounds, but may, by virtue of their shared experiences, in some cases be able to provide a more empathetic and pragmatically useful response to an individual's circumstances than those (such as family and friends) who are normally closest to him or her.

We are not aware of any research that either draws attention to this disconnection or speculates about the possible mechanisms and benefits of assisting those who are on bail to connect with one another. Such 'communities of disconnection' are, however, not at all unusual and from a theoretical perspective it could be argued that modern industrial societies function precisely by individualising all aspects of human experience - academic achievement, criminal culpability, economic advancement and so on (Foucault, 1977). Foucault, among others, describes in detail how this kind of "individualising gaze" helps to make large numbers of people "docile", productive and manageable.

However, in many other spheres of life, resistance to the bureaucratic machinery that seeks to turn collectives into manageable individuals is common. Examples are trade unions that mobilise the collective agency of workers against the machinations of management and Human Resources departments, political movements that enable (for example) students to rise up against excessive fees, and so on. Even severely disempowered groups such as sex workers have found ways of engaging in collective organisation to their mutual benefit (cf., Chateauvert, 2013; Vijayakumar et al, 2015; Jackson, 2016).

There could clearly be advantages for those who are out on bail to consider themselves as a collective - for example, in exchanging information about legal fees and procedures (e.g., alerting newcomers to the likelihood of numerous postponements before the actual court hearing starts), publicising the many injustices involved in the bail process (with a view to changing policies and legislation relating to bail), and providing emotional support (even if it amounts to nothing more than a sense of not being alone). We therefore suggest that this disconnectedness (and potential for connection) could be an important element in future bail research and activism.

A community of transience

The second way in which the bail community diverges from the sort of community typically envisaged by community psychologists is its status as a community of transience. The word "community" not only evokes visions of cohesiveness, but also of long-term stability (Thornton & Ramphele, 1988; Butchart & Seedat, 1990) - something resembling the Shire in Lord of the Rings, with community lore and traditions passed on from generation to generation.

Communities of transience should be distinguished from transient communities. Transient communities such as refugee settlements exist on a temporary basis and are constantly under threat of being disbanded. Communities of transience, by contrast, may have long-term stability, but those who form part of the community do so on a temporary basis.

People do not stay out on bail forever - they are eventually acquitted, found guilty and sentenced, or bail is revoked and they are re-arrested. Despite romantic visions of communities as places where people are at home for their entire lives, in reality most modern communities actually function in a similar way to the "bail community". People enter communities such as suburbs, university communities and workplaces knowing that they do so on a temporary basis, and even supposedly long-term communities such as churches and professional associations often have a constant influx and exodus of members. When seen from this perspective, a particular set of features of communities are thrown into relief, namely the various mechanisms that exist for gaining entry to and becoming established in the community, for preserving community values and knowledge and transferring them to new members, and for exiting the community without causing undue disruption. We discuss this in more detail below.

Institutional communities such as schools often have explicit processes in place for these contingencies, involving for example entrance exams, detailed syllabi to maintain stability despite changes in personnel, intricate systems of grading and accreditation to confer status on community members, and graduation ceremonies. More "organic" communities typically do not have such clear-cut provisions in place, but in one way or another do have to deal with these issues to maintain stability despite the transient nature of their membership. Where a community does not (yet) recognise itself as a community, as is the case for the putative bail community we have been describing, dealing with these issues become even more difficult. Again, we suggest that this misfit between the bail community and the sorts of communities (including transient ones) that Community Psychology typically focuses on, may well, perhaps counter-intuitively, provide rich opportunities for activism and research.

If we think of those who are out on bail as forming a community, and specifically a community of transience, then questions such as the following become pertinent: Who are, or could be, the "wise elders" who pass on explicit and tacit knowledge and skills to those who first enter the "bail community"? What is, or could be, the role of those who have entered and left the community on more than one occasion? What mechanisms are in place, or could be, to induct new members?

Ways forward

In this article we provided an overview of how bail functions in the contemporary South African criminal justice system, when that system is understood not as a linear process, but as inherently complex, messy and recursive. Seen from this perspective, bail becomes one of the staging posts in a carceral archipelago from which there is no ultimate escape.

We specifically explored research opportunities relating to the psychology of bail, including the community psychology of bail. Our hope is that the conceptual framework we presented here is useful in understanding bail from a psychological perspective and that the framework can guide future research relating to bail. Future bail research that is situated within a coherent framework is, we think, more likely to be of long-term value than piecemeal and unrelated studies.

Finally, we hope that our approach to framing a research prospectus for the (community) psychology of bail, could also be useful in work about the psychology of other aspects of the criminal justice system. Much as is the case with bail, each of the other spaces that are traversed in a person's "carceral career" can also be understood as a 'community of transience', throwing into relief the particular opportunities and challenges that are characteristic of such communities.

References

Adshead, G (2011) The life sentence: Using a narrative approach in group psychotherapy with offenders. Group Analysis, 44(2), 175-195. [ Links ]

Allan, A, Allan, M M, Giles, M, Drake, D & Froyland, I (2005) An observational study of bail decision-making. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 12(2), 319-333, DOI: 10.1375/pplt.12.2.319 [ Links ]

Bechtel, K, Lowenkamp, C T & Holsinger, A (2011) Identifying the predictors of pretrial failure: A meta-analysis evidence-based practices in action. Federal Probation, 75(2), 78-87. [ Links ]

Bowden, B (1999) Transience, community and class: A study of Brisbane's East Ward, 1879-91. Labour History, (77), 160-189. [ Links ]

Butchart, A & Seedat, M (1990) Within and without: Images of community and implications for South African psychology. Social Science & Medicine, 31(10), 1093-1102. [ Links ]

Cadigan, T P & Johnson, J L (2012) The re-validation of the federal Pre-trial Services Risk Assessment (PTRA), Federal Probation, 76(2), 3-9. [ Links ]

Chaskalson, J & De Jong, Y (2009) Bail, in Gould, C (ed) (2009) Criminal (in)justice in South Africa: A civil society perspective. Pretoria: Institute of Security Studies. [ Links ]

Chateauvert, M (2013) Sex workers unite: A history of the movement from Stone Wall to Slutwalk. Boston: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Department of Correctional Services. (2013) Annual Report 2012/2013. Pretoria: Author. [ Links ]

Department of Correctional Services. (2014) Annual Report 2013/2014. Pretoria: Author. [ Links ]

Department of Correctional Services. (2014) White Paper on remand detention management in South Africa. Pretoria: Author. [ Links ]

Department of Correctional Services. (2014) Annual Performance Plan 2014/2015. Pretoria: Author. [ Links ]

Durant, P (2005) Towards an integrated justice system approach. Paper presented at the CSVR Criminal Justice Conference, Gordon's Bay, South Africa, February 7-8. Retrieved from: http://www.csvr.org.za/wits/confpaps/durand.htm [ Links ]

Foucault, M (1977) Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York: Random House (1975-French). [ Links ]

Glaeser, E L, Laibson, D & Sacerdote, B (2002) An economic approach to social capital. The Economic Journal, 112(483), F437-F458. [ Links ]

Hoerl, C (2015) Tense and the psychology of relief. Topoi, 34(1), 217-231. [ Links ]

Jackson, C A (2016) Framing sex worker rights: How US sex worker rights activists perceive and respond to mainstream anti-sex trafficking advocacy. Sociological Perspectives, 59(1), 27-45. [ Links ]

Karth, V (2008) 'Between a rock and a hard place': Bail decisions in three South African courts. Cape Town: Open Society Foundation. [ Links ]

Leggett, T (2005) Just another miracle: A decade of crime and justice in democratic South Africa. Social Research, 72(3), 581-604. [ Links ]

Lerner, M J & Montada, L (1998) An overview: Advances in belief in a just world. Theory and methods, in Montada, L & Lerner, M J (eds) Responses to victimizations and belief in a just world. New York: Plenum Press. [ Links ]

Limb, P (2008) Nelson Mandela: A biography. London: Greenwood Press. [ Links ]

Lipsey, M W & Cullen, F T (2007) The effectiveness of correctional rehabilitation: A review of systematic reviews. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 3, 297-320. [ Links ]

Mamalian, C A (2011) State of the science of pretrial risk assessment. Rockville, Md: Pretrial Justice Institute. [ Links ]

Mandela, N R (1995) Long walk to freedom. Boston: Little Brown. [ Links ]

Masutha, M (2014) Correctional Services budget vote speech - 2014/2015. National Assembly (16 July), Cape Town, South Africa. [ Links ]

Menard, S & Pollock, W (2014). Self reports of being falsely accused of criminal behaviour. Deviant Behavior, 35(5), 378-393. [ Links ]

Moller, V (2005) Resilient or resigned? Criminal victimisation and quality of life in South Africa. Social Indicators Research, 72(3), 263-317. [ Links ]

Omar, J (2016) Penalised for poverty: The unfair assessment of 'flight risk' in bail hearings. South African Crime Quarterly, 57, 27-34. [ Links ]

Packer, H L (1968) The limits of the criminal sanction. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Pardo, M S & Allen, R J (2008) Juridical proof and the best explanation. Law and Philosophy, 27(3), 223-268. [ Links ]

Putman, R (2013) Bowling alone: America's declining social capital, in Lin, J & Mele, C (eds) (2013) The urban sociology reader. 2nd edition. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Rabuy, B & Kopf, D (2016) Detaining the poor. Northampton: Prison Policy Initiative. [ Links ]

Sacks, M & Ackerman, A R (2015) Bail and sentencing. Does pretrial detention lead to harsher punishment? Criminal Justice Policy Review, 25(1), 59-77. [ Links ]

Schönteich, M (2015) Pre-trial detention in sub-Saharan Africa: Socio-economic impact and consequences. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology, Special Edition No 1/2015: Change in African Corrections: From incarceration to reintegration, 1-17. [ Links ]

Schnittker, J & John, A (2007) Enduring stigma: The long-term effects of incarceration on health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(2), 115-130. [ Links ]

Schumann, R (2013) Gendered bail?: Analyzing bail outcomes from an Ontario Courthouse. MA thesis, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada. [ Links ]

Sherrin, C (2012) Excessive pre-trial incarceration. Saskatchewan Law Review, 75(1), 55-96. [ Links ]

Silver, M (1999) Love, hate, and other emotional interference in the lawyer/client relationship. Clinical Law Review, 6(1), 259-313. [ Links ]

Thornton, R & Ramphele, M (1988) The quest for community, in Boonzaier, E & Sharp, J (eds) South African Keywords. Cape Town: Phillip. [ Links ]

Vijayakumar, G, Chacko, S & Panchanadeswaran, S (2015) 'As human beings and as workers': Sex worker unionization in Karnataka, India. Global Labour Journal, 6(1),79-96. [ Links ]