Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Psychology in Society

On-line version ISSN 2309-8708

Print version ISSN 1015-6046

PINS n.56 Stellenbosch 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8708/2018/n56a3

ARTICLES

Whiteness and non-racialism: White students' discourses of transformation at UCT

Ruth Urson; Shose Kessi

Department of Psychology. University of Cape Town. Cape Town

ABSTRACT

Recent years have seen black university students in South Africa rallying against institutional racism and mobilising for systemic change in higher education, in response to the slow progress of transformation. Against this backdrop, little is known about white students' perceptions. In this paper, we examine white students' understandings of non-racialism and their roles in racial transformation. A Whiteness Studies framework was used to investigate how white students talk about transformation and race at the University of Cape Town (UCT), and what role these discourses play in transformation. Four focus groups were conducted in 2015 with 27 white UCT students from different programmes of study, and a discourse analysis incorporating Foucauldian principles was used to analyse these discussions. Three discursive sets of Old Order Whiteness, Defensive Rainbowism and a developing set of counter-discourses were identified, according to the influence that broader discourses used in constructing race and transformation had on white students' positioning. The use, interrogation and challenging of these discursive sets by participants demonstrates a discursive negotiation and fracturing within this sample group, with potential implications for non-racialism and the transformation process.

Keywords: Whiteness, transformation, non-racialism, discourse analysis, higher education, South Africa

Introduction

On 10 March 2015, a University of Cape Town (UCT) student named Chumani Maxwele wore a placard stating, "Exhibit white arrogance @ UCT" as he emptied a container of human excrement onto the university's statue of British colonialist Cecil John Rhodes (Bester, 2015). This prompted the formation of a collective of black1 UCT students named Rhodes Must Fall (RMF) that successfully campaigned for the removal of the statue from UCT's campus, preceding ongoing protests for the decolonisation of higher education. RMF's complex demands, which included systemic change towards black liberation from colonial power relationships and the "Africanisation" of universities (Rhodes Must Fall, 2015), amplified a growing criticism of South African higher education transformation, and questioned the institutional discourse of "non-racialism" at UCT. As protests continued into university-wide movements and later into an enduring national university shutdown under the banner "#FeesMustFall" (Baloyi & Isaacs, 2015), the repeated grievances of black university students in the era of transformation took a new spotlight.

Transformation as policy or practice

Transformation here refers to measures prescribed to address the racial inequalities left by apartheid (Ramsamy, 2007). It derives from non-racial values contained in the Constitution (1996) and echoed in the national Higher Education Act 101 (1997), Education White Paper 3 (Department of Education, 1997), and institutional policies mandating the reconstruction of apartheid structures that privileged white South Africans over black South Africans. Racial transformation efforts in South African higher education institutions are primarily two-fold. They aim to improve representation, by using equity measures to shift the racial demographics of students and staff, and also aim to address historical privilege, disadvantage and power through measures like improving student support and reforming institutional cultures (Soudien et al, 2008). However, in a national overview of literature and stakeholder input, Soudien and colleagues identified gaps between these aims and the practical reality. While demographic transformation does show some numerical change in racial representation, the university experience and chances of success still differ along racial lines.

For example, students still report informal racial segregation at historically white South African universities (Steyn & Van Zyl, 2001; Erasmus & De Wet, 2003; Koen & Durrheim, 2009; Schrieff, Tredoux, Finchelescu, & Dixon, 2010; Higham, 2012; Suransky & van der Merwe, 2016). Of note, while some black students reported being racially stereotyped, having their competence undermined by white students, and being excluded when working in racially diverse groups (Steyn & Van Zyl, 2001), white medical students generally constructed inter-racial interactions positively or claimed not to see racial differences (Erasmus & De Wet, 2003). An investigation of students' experiences at historically racially segregated South African universities further showed that while explicit racism was generally controlled, deeper inclusion had not been achieved (Higham, 2012). At the historically white University of Cape Town, black students reported feeling marginalised by the dominance of whiteness, exemplified by the primarily white academic staff and the Eurocentric symbolism on campus (Steyn & Van Zyl, 2001; Erasmus & De Wet, 2003; Kessi & Cornell, 2015). The dominance of white institutional culture and language and lack of acknowledgement of African scholarship are noted barriers to transformation (Steyn & Van Zyl, 2001; Erasmus & De Wet, 2003; Bangeni & Kapp, 2005; Soudien et al, 2008; Higham, 2012) which contradict the national policy goal of providing inclusive education which is both globally competitive and locally relevant (Department of Education, 1997).

Assessing non-racialism

In examining the causes of these gaps, Erasmus and De Wet (2003) allude to the role of non-racialism, a value adopted by the African National Congress (ANC) as the ultimate goal of transformation efforts (Ramsamy, 2007). Despite its significance, its ambiguity was demonstrated in focus groups of South African citizens (Bass et al, 2012) and leaders (Anciano-White & Selemani, 2012), whose participants produced divergent definitions.

While the ANC's non-racialism initially referred to the establishment of a democratic nation in which a common South African identity would replace racial identities, the structural salience of race made this difficult (Ramsamy, 2007). So, a Rainbow Nation or multiracial rhetoric was adopted, but still called non-racialism (Ramsamy, 2007). In this conceptualisation, races are acknowledged but regarded as equal and contributory towards a united South Africa (Bass et al, 2012). This, however, has been criticised for reifying race as an essential human quality, rather than understanding racial categories as social constructs with material effects or differences in lived reality (Suttner, 2012; Taylor, 2012). Biko (1987) argued that these shallow forms of non-racialism are impossible while psychological and structural racial inequalities still exist. As white South Africans have benefited materially and psychologically from apartheid, promoting equal treatment of different races prevents systemic racial inequality from being addressed and maintains white privilege (Biko, 1987; Delgado & Stefancic, 2012). Deeper non-racialism would rather be the result of first addressing structural and psychological racial inequality (Biko, 1987; Taylor, 2012).

Discourses of whiteness

One important structural factor opposing non-racial transformation policy goals is whiteness, the systemic privileging of white groups that acts to oppress and exclude black groups. Whiteness shapes identity and privilege, provides a perspective from which white people view others and the world, and prescribes certain beliefs and practices (Frankenberg, 1993). Frankenberg (1993), in her landmark interview study of white American women, argued that in societies that systemically oppress black people, whiteness becomes normative and invisible, thus preserving itself.

This is influenced by discourse, the production of knowledge through language forms and its reciprocal construction, challenging or legitimisation of power relations and subjectivities (Foucault, 2002). Dominant discourses both dictate and are validated by hegemonic social, political or institutional systems, and counter-discourses challenge and are challenged by these systems (Willig, 2008). The boundaries of available discourse interact reciprocally with the boundaries of material reality (Foucault, 2002). As such, discourses and counter-discourses influence how reality is constructed, and reality influences which discourses can be used (Wiggins & Riley, 2010).

Accordingly, different studies have identified discourses used by white South Africans and their operation in a post-apartheid context. Steyn (2001) demonstrated how discourses support a variety of post-apartheid white identities, including those unequivocally supporting white superiority, those constructing white people as victims of the new social order, those coming to terms with a new minority identity in South Africa, those disconnecting whiteness from its apartheid past, and those acknowledging and confronting whiteness. White South Africans' discourses have also been shown to operate to resist transformation (Steyn & Foster, 2008) and to maintain systems of inequality that underlie white privilege (Wale & Foster, 2007).

One such discourse constructs non-racialism as colour-blindness, which disregards race and its relationship with privilege (Steyn, 2001; Wale & Foster, 2007). Similarly, white medical students used the term reverse racism in describing affirmative action measures that admit black students to university with lower marks as unfair (Erasmus & De Wet, 2003). The term allows white South Africans to ignore the structural racism that maintains their privilege (Steyn, 2001; Wale & Foster, 2007) and black students' exclusion (Kessi & Cornell, 2015). This use of non-racialism also places the weight of race awareness and discomfort on black students, who then have to take on the burden of transformation, changing themselves or denying or internalising experiences of racism under pressure to fit into the white university culture (Erasmus & De Wet, 2003). These discourses marginalise black students (Steyn & Van Zyl, 2001) and subject them to white paternalism (Wale & Foster, 2007).

Other discourses normalise whiteness and equate blackness with a lowering of standards. This "White Talk" (Steyn & Foster, 2008: 26) comprises discourses used by white South Africans to support current non-racial values, while invoking panic at the full inclusion of black South Africans in society and its leadership. This tension previously manifested publicly in the long-standing debate between racial equity in admissions and academic excellence at universities (Kessi & Cornell, 2015). At UCT, this has been exhibited in suggestions that racial equity measures promote a lowering of university standards (Kessi & Cornell, 2015). Additionally, Steyn and Van Zyl (2001) identified a common assumption that the whiteness of educational institutions maintains internationally competitive educational standards. White Eurocentric education is therefore normalised while further transformation, of institutional culture, curricula and pedagogy, is associated with lowered standards (Soudien et al, 2008).

Against this background, this article considers white students' responses to the protests at UCT in 2015. On the surface, these responses seem varied, ranging from firm opposition to attempts at allied support, with the latter including the foundation of the White Privilege Project (2015) (now Disrupting Whiteness). Disrupting Whiteness (DW) is a collective of white UCT students and staff mandated by Rhodes Must Fall to address racism in the white university community through education initiatives. These initiatives include the creation of spaces for conversation between white students on issues relevant to whiteness, as well as guerrilla-style awareness campaigns and protest initiatives aiming to "disrupt whiteness" at UCT and in the broader South African context. The establishment of such a project seemed to represent a potential shift in the visible use of race discourse among white students, and particularly, their grappling with and challenging of common discourses of whiteness.

As such, this study places importance on examining and critiquing white students' constructions of race and understandings of non-racialism, while acknowledging whiteness as a fluid and multi-faceted systemic construct that changes across time, place and person (Green et al, 2007; Hartmann et al, 2009). Grounded in the context of the aforementioned student protests, this paper reflects on the discourses used by white students at UCT in talking about non-racialism and higher education transformation, the main question being: How do white students talk about transformation and race at UCT, and what roles do these discourses play in transformation?

Method

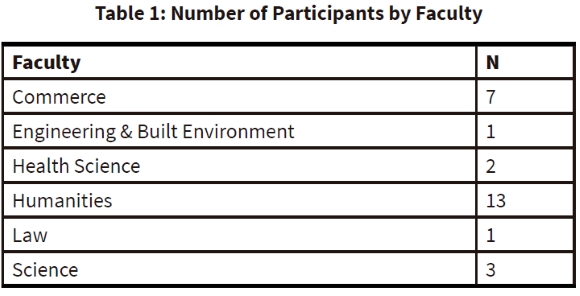

Between June and August of 2015, four focus groups (FG) were conducted with four, nine, seven and seven participants respectively, with attendance based on participant availability, but where possible also on gender, year of study and faculty (see Table 1). Invitations for white UCT students' participation in transformation discussions were sent through the UCT Student Research Participation Programme (SRPP), the White Privilege Project (2015), advertisements shared on UCT's campus and on social media, and by word of mouth. 27 participants were recruited, 14 male, 13 female, and of these, 16 were undergraduate students, 9 were postgraduate students, and 2 were students completing courses for non-degree purposes. An online screening questionnaire was used to obtain demographic details and pseudonyms have been used in the presentation of findings to protect participants and ensure anonymity.

Each group met once, for 60 to 90 minutes, in a classroom in the UCT Psychology Department. After obtaining informed consent and introducing the general topic of discussion, an extract from UCT's Transformation Policy was given as a prompt: "UCT is committed to the goal of non-racialism."2 Follow up questions and probes explored participants' understandings of non-racialism and other aspects of the research question. Discussions were recorded and later transcribed and analysed.

This study was notably influenced by the concurrent protest climate on campus. Focus groups were conducted shortly after the removal of the Rhodes statue, and before a nation-wide student fees protest and university shutdown (Baloyi & Isaacs, 2015). Participants of this study were exposed to a climate in which Rhodes Must Fall's calls to decolonise universities and deconstruct institutional whiteness and racism were circulating widely. In this context of racial tension on campus, this study invited only self-identified white South Africans to share their views on transformation, on a poster bearing the broad slogan, "Let's talk about transformation!" All interactions with participants were conducted by the first author, a white female Psychology Honours student. Due to the broad aim communicated to the public, and being seen as a white "insider" and sharer of similar opinions, some participants perceived the study's aim as being to offer a safe space for white voices without fear of being antagonised.

Erica (FG3): "... and it's nice to just be able to discuss it without the risk of um, having your head bitten off."

In contrast, some students came to learn more about what was circulating in protest discourses and others came to educate.

Mary (FG2): "It was quite exciting for me, because spaces like these are important so white people who aren't, necessarily very privy to knowledge of their own privilege get a chance to interact with people who might be more educated..."

Comments like these could be interpreted as an indication of the significance of white conversational spaces in the construction of white identity, whether this results in the further consolidation of a whiteness that is resistant to change, or the development of new forms of whiteness. The exchange above indicates the potential impact that the focus groups could have towards the latter purpose. However, some participants were also suspicious of the researcher's intentions, and this had to be carefully managed; for example, one participant emailed the researcher out of concern that their name and opinions would be exposed to the media or external stakeholders. There was also an evident tension in the dynamic between participants, where common discourses and constructions of whiteness were not unanimously accepted and were instead challenged and negotiated within the space that the focus groups offered, as outlined in the results. As such, the creation of these spaces required consideration not only of how whiteness can be discussed, but also of how whiteness operates in a discussion space. It is also important to acknowledge that in the absence of a black critique, these conversations ran the risk of reifying a white racial imaginary (Ahmed, 2004; Dyer, 2005).

Discourse analysis

The data were analysed using Willig's (2008) discourse analysis, which incorporates aspects of Foucauldian Discourse Analysis (FDA). While not a prescribed method, but rather a collection of discourse theory influenced by Foucault's writing, FDA generally examines how knowledge claims are situated within discourses to become "true," in relation to history, power and subjectivity (Hook, 2001), and how these are linked to broader contexts and ideologies (Arribas-Ayllon & Walkerdine, 2007). FDA allows analysis of how constructions like race arise in context and acquire power, and what they can achieve.

Findings and discussion

Across the focus groups, three broad discursive sets of Old Order Whiteness, Defensive Rainbowism, and a developing set of counter-discourses were identified in participants' talk of race and transformation. The term discursive set is used here to describe bodies of discourses with similar origins and effects that, in some cases, participants utilised, and in others, they challenged or negotiated to produce noteworthy tensions and convergences.

Old Order Whiteness

Old Order Whiteness is the name given to a discursive set drawing from colonial discourse, the system of meaning within which the dominance of one nation over another is justified (Ashcroft, Griffiths, & Tiffin, 1998). It bases knowledge on assumptions of colonial norms, justifying the coloniser's superiority (Ashcroft et al, 1998) through the "master narrative of whiteness" (Steyn, 2001: 3) to construct Africa as uncivilised and Western civilisation as superior, and situating white identity within this. At its centre is a justification of colonialism and racial inequality using an evolutionary discourse.

Greg (FG4): "So, in the natural world there's this kind of thing of survival of the fittest ... So don't you think that in some sort of way - that's sort of what happened when the Brits came down. They had superior technology, superior power. They had fewer people and ... they still overcame the masses, you know what I mean? Just because they were more powerful. So in a sense, and again, this is not what I'm thinking, but you can sort of feel like, so they were, black people were conquered, they were dominated by white people. Is it [sighs], is it something for us to sit and cry about twenty, thirty years later?"

Scott: "... But that is deeply wrong, I think ... and that might be evolutionary or something, but by all means, we should be against that and that's what our morals are about, protecting the, the - [Greg: "Weak"] weaker from the more powerful."

Greg's echoing of documented white discourses is reminiscent of theories like Social Darwinism which consider race as biological rather than as a social construct, and justify oppressive systems like apartheid, citing "superior" qualities of white people to justify their power over "savage" black people (Dubow, 1995). Such arguments construct the societal power of white groups as a product of inherent superiority, without consideration of the oppression underlying that power, and situate the white identity within this as that of a "winner" rather than an "oppressor". Distancing phrases like "this is not what I'm thinking . " further suggest tension between the argument's broader social taboo and its use in white circles.

Contrarily, Scott, while accepting the evolutionary discourse and white "winner" narrative, challenged its "logic" with an appeal to morality. This nuance was a notable challenge in a boisterous, slightly male-dominated group but while appearing empathetic, was easily led back to colonial "logic" of strength and weakness by Greg's interjection, particularly to a paternalistic discourse equating blackness with weakness. Especially in this focus group, drawing on this "logic" opposed not only empathy but all references to emotion. For example, Greg's final reference to apartheid oppression not being "something to cry about", uses the disparaging colonial language of emotion as being weak, trivial, or child-like. It seemingly reinforces constructions of strength and weakness, with white groups "getting on with the job" and black groups as emotional, weak, or childish, delaying progress by "playing the victim".

It seems likely that this disparagement of emotion is influenced by the intersection of colonial logic and patriarchal conceptualisations of emotion as a weakness of women. Whiteness is not homogenous, and intersecting systems of race and gender can support and challenge each other to bring nuance to white discourses and experiences (Crenshaw, 1995). The following exchange exemplifies this, whereby the articulation of emotionality that was used to undermine black groups and their protest was also used to undermine women as "too emotional".

Talya (FG4): "I think, the problem with this whole racist, racialism, race aspect is that as human beings . we function by emotions, we live our lives with our emotions."

Greg: "Well women do." [Men in the group laugh]

This undermining of emotion was not restricted to male participants, and tension further emerged in female students' contrasting constructions of white students and the "white" institution of UCT, and RMF, the "black" movement. Participants referred to RMF as uncivilised, irrational, and emotional, describing them as saying, "screw what I'm learning at varsity, and then they go and throw stuff around and scream on the fields" (Lucy, FG3). Conversely, rationality was favourably associated with white civilisation and the objective pursuit of knowledge. Accordingly, Erica argued that "there's no platform for you to disagree just like you know, based on facts and evidence, and try and be as objective as possible... without you know, having dung thrown at you" (Erica, FG3). Using this assumption of white voices' logic and black irrationality, participants gave credence to white voices to delegitimise movements like RMF for not doing things the "right" way. This paternalism, a key part of colonial discourse, is further evident in the following extract referring to RMF:

Jenna: "Maybe a part of uh, getting a - essentially it's non-white people are getting a voice, that maybe they didn't have as much before, and like anyone who's learning something new, um, as people who have had voices for centuries, we can also be understanding of the fact that people make mistakes, and how they capitalise and harness that voice-" [Erica: "Mm"]

Interestingly, Jenna attempted to disrupt the discourse of white authority itself, by raising awareness of how white voices have long been privileged. At a critical level, her language is notably tied to whiteness, including the use of "non-white", an apartheid term which suggests blackness is a deficit in whiteness, the classification of RMF's actions as "mistakes", which asserts white authority, and the paternalistic description of black students' voices as something new they're learning, rather than something silenced by racism. As such, the power of her challenge to white authority utilised the discourse she was attempting to oppose. Still, it was received thoughtfully by other participants, raising the question of whether this was an unconscious re-assertion of white authority in the face of discomfort, or rather an attempt at reaching the others with a conscious use of their own language. The latter would suggest that addressing whiteness, as a white person, is a complicated endeavour, which does not simply entail echoing black students but rather involves differing tactics, perhaps even borrowing from Old Order Whiteness to translate black students' demands into the accepted languages of whiteness.

The challenge of negotiating these familiar discourses while attempting to remain aware of one's privileged positionality was evident in other comments and interactions between participants. For example:

Simon (FG2): "Okay uh, suppose you know how to build a house. Now a bunch of people come and say like, we've never been allowed to build a house, we want to build a house now, and we want you to do it like this."

Mary: "Okay ."

Simon: "And you see a flaw in it - like, if I build it like that it's gonna collapse. But they want you to build it that way."

Mary: "Ja, ja. And that's a great analogy. I don't, really know how to answer that, but then again if we're saying, 'We know what's best for you - "'

Simon: "Yeah I -1 know - "

Mary: [louder] "- it's a difficult thing, ja, no I know what you're saying - "

Joe: "The problem with the house analogy is that in the case of like architecture, it's quite easy to see what's the right way to - "

Mary: "Exactly! But with political things, the lines get blurry and... ja."

Simon's house analogy is seemingly an argument against broader systemic change, arguing for different builders, but a blueprint still controlled to some extent by white groups. There's an assumption that "the white way is the right way", or as Mary puts it, "We know what's best for you". Interestingly, Mary, who had been arguing that the white role in transformation is to follow black leadership, seemed to be torn between agreeing with Simon, and trying to use the critical race perspectives she'd previously been drawing on to articulate a reasoned disagreement. Joe's interjection allowed participants to avoid resolving this tension beyond declaring it complicated. This interaction demonstrated how participants struggled to navigate away from the entrenched colonial logic of Old Order Whiteness to find new ways of "talking white" and resolved the tension with avoidance when new perspectives failed to fill the explanatory gap.

Old Order Whiteness therefore operates to sustain whiteness by normalising colonial ideas and structures, and by affirming white authority and "standards" while dismissing opposition as emotional or illogical. A racial hierarchy is suggested, but voiced within this "non-racial" climate in language of "logic" and what is "right," rather than race. Notably, this language is tied to an undermining of emotionality which is used to delegitimise black students in ways similar to its use in undermining women. Its use by participants of all genders indicates the pervasiveness of these discourses, and this language seems to facilitate the reinforcement of power held at the intersection of whiteness and patriarchy, suggesting that changing constructions of whiteness cannot happen in isolation of other intersecting systems of privilege and oppression (Crenshaw, 1995).

However, various participants demonstrated a limited willingness to grapple with their positionality and morality in relation to the discourses of Old Order Whiteness, attempting to challenge colonial "logic," highlight white privilege, or deconstruct white authority. This utilised various means such as an explicit acknowledgement of emotion; the apparent translation of opposition into the accepted languages of whiteness; and attempts to resolve old questions with new discursive resources. There is therefore a tension in the old order of whiteness, as participants attempted to negotiate new and old frames of reference, complexifying their operation in this context.

Defensive Rainbowism

A second discursive set stems from the Rainbow Nation discourse, the post-1994 ideal describing a South Africa where different equalised races form a united national identity (Mandela, 1994). A white identity situated within the Rainbow Nation discourse is one devoid of association to a white racist apartheid identity (Steyn, 2001). This discourse has been criticised for its potential for "smug rainbowism" (Cronin, 1999: 20), a shallow form of peace in which the struggle for equality is considered over before it begins, leaving South Africa with pervasive racial inequality well into its official democracy.

As such, arguments like "I was born in 1995, I had nothing to do with apartheid ..." (Holly, FG4) demonstrate an adoption of the born-free identity, which in South Africa denotes the generations born after apartheid and argued to be unbound by race. This notion of freedom is criticised for neglecting racialised post-apartheid material disparities (IRR, 2015). In this study, a born-free discourse expectedly emerged to construct a "colour-blind" white identity, disconnected from the history of apartheid, and distanced from race, racism and privilege.

Daniel (FG2): "But I mean, I don't know how to deal with um, addressing a race problem because I don't see a race problem?"

Julia: "Ja I completely agree with that - when I walk out of UCT I don't see, I mean people will just naturally- if you have stuff in common, people will just naturally bunch together."

As such, participants could be distanced from their apartheid-era white identities and be repositioned as "non-racist". The born-free discourse thereby prevents acknowledgement of white privilege, rather described by participants as acquired through means unrelated to race, assuming the individualism inherent in a liberal democratic capitalist system (Wale & Foster, 2007). Privilege was equated with individual wealth rather than structural racism, and participants who did not identify as wealthy denied their privilege, while others considered it earned through individual hard work and merit. Greg (FG4) expressed both:

Greg: "Isn't it now pushing in the other direction, because the other day I arrived on campus and I get off my bike and I'm rushing off to a lecture and one of the campus workers stops me and was like, 'Hahaha, me and my friend were just saying how all of the white kids are the ones with the bikes, because your parents have bought it for you.' And I actually stood like in awe and - [Talya: "That's the shit thing - "] was like, 'I'm sorry, I took a gap year last year and worked 7 days a week to buy this for myself. I have to get to class, fuck you.'"

Here, an association of his whiteness to wealth prompted Greg to become aggressive. His response exemplified white fragility, where whiteness is well-hidden and sheltered by its dominance in society and so, any amount of racial stress for white people is amplified and prompts anger, guilt, or other defensive reactions (DiAngelo, 2011). This hypersensitivity reveals the complexity of the white born-free identity for participants like Greg, who do not consider themselves wealthy. Race and class privilege are conflated, rather than being seen as separate but intersectional, and one's white privilege is dismissed by dismissing one's class privilege (Wale & Foster, 2007). Interestingly, the heated attempt to justify his relative privilege paradoxically ignored the privilege of being able to take a gap year to buy a bike, and also utilised the privilege of being able to ignore how race affects his life, evident in the disparate positioning of a university's white students and black campus workers.

Responses such as these were not universal among participants. Hannah (FG1) conversely critiqued the notion of "born-frees" and the Rainbow Nation discourse as limiting possibilities of facilitating change.

Hannah: "I mean having been born in 1994, I'm like a so-called born-free, and ... it's the idea that has been constantly drilled into us, like, 'Don't, see colour, you are non-racial, you are non-racial,' only maybe it kind of backfires in the sense that then people hide behind that, 'cos having not been taught . that actually we do live in like a racialised society, but we can make it a better place and we can change it, instead of 'Let's all just hold hands and sing 'Kumbaya' around the fire.'"

This challenge to colour-blindness describes race as something to acknowledge rather than ignore, and racism as something to challenge on a societal level rather than something only to avoid explicitly practicing. This again deviates from dominant discourses, and highlights tension in the born-free discourse for white participants. Alternatively, with an understanding of non-racialism as colour-blindness, the white post-apartheid claim is rather to be born-free from the acknowledgement of race and white privilege, and appropriates victimhood based on the diminishment of this privilege.

As such, it is noteworthy that while race was ignored by participants inasmuch as it privileges white people, it was recognised in "reverse racism" when the loss of white privilege was at stake. This well-documented "reverse racism" discourse arose strongly in most focus groups when discussing UCT's affirmative action admissions. This highlights the divergence between understandings of racism, as discrimination arising from prejudice, versus systemic oppression resulting from the embedding of prejudice in societal structures through the exercise of power (Operario & Fiske, 1998). Although equity measures discriminate along racial lines, they are set in place to address systemic racism, and would not constitute racism when race is understood as a social construct built into systems of oppression.

Gabi (FG3): "... and yes we've had privileged backgrounds, relatively speaking, but what does it actually mean for us and our future careers, cos we now face the opposite of that, in that we're a minority ... and affirmative action policies will disadvantage us now. So I find it interesting that you've got to go through this process of reverse racism, in a way, to get to non-racialism. That we've had the pendulum swinging all the way in the white favour for so long, it's got to swing almost all the way to the other side before you find that balance" [Various members: "Mm"].

Jenna: "So there is - in terms of reverse racism, um and the pendulum swinging. If you've historically your entire life had privilege, like from the beginning of being white, zillions of years ago, I mean, you can't really reverse that ... You'll still have a legacy of you - you historically being the person or group of people that, you know, made thousands, millions and zillions of people's lives really shit."

Gabi's cautiously-worded reference to "reverse racism" speaks to the fear of living as the minority white people actually are, not the powerful cultural and economic majority they have become accustomed to being. It is a narrative of victimhood and fear, focusing on the personal consequences of change. In contrast, Jenna challenged "reverse racism" by adopting a narrative of culpability and responsibility, acknowledging white privilege and demonstrating an awareness of the whiteness in which "reverse racism" finds meaning. Interestingly, while "disruptors" of common whiteness discourses like Jenna were present in all groups, the groups varied in their reception of these interjections, with this group being particularly receptive. The bigger-picture narrative of accountability Jenna communicated acknowledges the historical context of whiteness, not just its non-racial definition of "skin colour", and therefore understands affirmative action as systemic equitable treatment, rather than simply discrimination.

The emotive component of Jenna's comments, demonstrating anger at the injustice underlying their collective privilege, is notably different to the abhorrence of emotion in colonial discourse. However, while colonial discourse undermined emotionality in favour of "rationality," Defensive Rainbowism largely justified the language of emotion in reference to feelings like anger and offence prompted by perceived white victimisation and marginalisation.

Lucy (FG3): "I get quite angry with the way that there is almost, like, they always single us out. I feel a little insulted when I walk around and 'We are black' is written all over the walls at UCT... I know it's like to promote their race, but I mean they're putting everybody else down ..."

Erica: "Um, ja it does go the other way as well, I mean it's not just white people who can be racist ..."

Caroline: "... and I think this whole Rhodes thing has really aggravated people . And you're suddenly having all your power taken away, and you're being called all these things and it's easy to get offended - "

Although such language of emotion and victimisation could seemingly present a pathway for empathy with black students, it did not have such an effect. Rather, under pressure, the unifying "born-free" discourse seemed to evolve towards a form of social competition centred around victimhood. While the question posed to these participants had been about the role of white students in transformation, the discussion had quickly turned to complaints of white victimisation, and participants did not deprioritise this to discuss the broader picture of transformation towards black dignity and racial justice. This again demonstrates white fragility (DiAngelo, 2011) as well as white fright, the construction of white groups as the victims of black retaliation and power (Dolby, 2001). In a more colloquial sense, the behaviour of white groups claiming victimhood or emotional precedence in response to black voices' prioritisation has been observed frequently enough to earn the nickname white tears among young social media users (Loubriel, 2016).

These differences highlight a discursive gap between those who understand race critically as a social construction built on a legacy of oppression, versus simply an irrelevant biological characteristic. The former leads white students like Jenna to view whiteness as a systemic construct which can be understood from personal examination, and opposed without taking personal offence, shifting energy in the direction of broader social change. In contrast, the latter caused an acknowledgement of whiteness to be de-contextualised, personalised, and taken as threatening or victimising, and this offence overpowered the identification of systemic racism. As such, unlike in discourses of Old Order Whiteness, emotion was acknowledged and accepted within transformation. However, its application was limited and the resultant centring of whiteness presented as an obstacle to transformation, as it prevented its discussion, and allowed participants' ignorance or refutation of white privilege while intentionally or unintentionally concentrating their efforts on preserving it.

In constructing the Rainbow Nation as a present state rather than an ideal, participants performed transformation through Defensive Rainbowism, becoming "born-free" of responsibility for or acknowledgement of the privilege they have been afforded by historical white racism. Within this discourse, "rainbowism" finds its primary function as a form of defence against perceived white victimisation or loss of privilege. Positioning themselves as members of the "Rainbow Nation" but as victims within it shifted the responsibility for transformation to others, while offering participants freedom in the South Africanisation of their white identity. The resultant fixation on "reverse racism" prevented participants from being able to meaningfully discuss racial transformation within its historical and political context. However, there also appeared a disillusionment and frustration with these steadfast discourses, highlighted by dissenting voices in the groups.

Counter-Discourses

The counter-discourses emerged as a developing discursive set drawing from newer sources including, within the UCT context, RMF, the White Privilege Project, social media, and critical social science courses. Participants utilised more critical perspectives, viewing race as a social construct with material and social correlates, acknowledging white privilege and demonstrating a willingness to do the "race work" (Erasmus & de Wet, 2003: 25). Beyond this, it seemed that participants were turning increasingly away from the national liberal discourse and its filtration into UCT's transformation policy, and towards sources which offered understandings more congruent with the reality to which they had been made aware. The following comments exemplified this divergence from hegemonic discourses of whiteness.

Megan (FG1): "People use excuses to sort of not interact, like 'class' or 'education'... and it's difficult to sort, of have that conversation with those people because they are all, Ί don't see race, what are you talking about? I just happened to conglomerate with these random people who look exactly like me.'"

Matt: "Call a spade a spade. Non-racialism is new millennium racism."

Matt's and Megan's comments suggest a disillusionment with shallow non-racialism and its limitation of discursive resources with which to imagine and form a constructive, collective white identity which addresses the racism of whiteness. Their conversation highlighted the crisis of whiteness for students who had been made aware of their proximity to racism. Accordingly, certain focus groups allowed for a space to process and reconstruct a divergent understanding of non-racialism beyond "colour-blindness".

Joe (FG2): "I mean I guess I'd argue that non-racialism should be a point where we recognise that races are different and that races are represented in the colour of skin, but it is in fact irrelevant. Like institutionally and subtly and in terms of all that stuff."

Benjamin: "So it sounds like what you're saying is that we should arrive at a place of post-racialism, rather than non-racialism because -"

Joe: "Ja!"

Mary: "Oh that makes sense-"

Julia: "Makes sense."

When critiques of non-racialism were somewhat accepted among participants, they expressed disgruntlement with transformation as "transcending race" and increasing demographic diversity, without changing exclusionary structures and institutional culture within the university.

Matt (FG1): "and for UCT's claim that it wants to be the top African university, but it has no interest in . understanding race, that it wants to transcend it . uh, ja, that's hugely problematic. Who gets to say when we transcend race?"

Intertwined with the more cognitive counter-discourses was an emotionality that differs from the expressions captured in discussions of the previous discursive sets. Mainly, students voiced anger and frustration in relation to racism.

James (FG1): "Like, my goodness, the number of times I've sat in my uncle's car and he's said something and like, I just used to like sort of let it die out. And now, I'm more open to be challenging him on it. But his mind is so - ahh - it's so frustratingly set."

Such frustration indicates students' critical thinking and willingness for action, and also demonstrates a new discursive fracturing of whiteness, into a "bad" and a "better" whiteness. Seeking to re-shape whiteness, by addressing white discourses and constructions seen as harmful or undesirable, holds potential for imagining new ways of being white in the context of post-apartheid South Africa. This also holds the potential danger of allowing a simplistic acceptance of oppositional "good" and "bad" constructions of whiteness and a denial of a "bad" white identity. Similarly, to the issues identified in relation to other discourses of whiteness, such thinking could prevent the achievement of voiced goals of re-imagining and "disrupting" whiteness by focusing efforts rather on preserving a positive white identity. The result then would not be the apparent radical negotiation of white discourse in a manner that facilitates identity-building and systemic action towards social change, but rather an individualistic acceptance of a "better whiteness" that allows a more comfortable or positive white identity by distancing oneself from "bad whiteness".

Megan (FG1): "I've seen a lot of alumni, and uh, PhD students very angry with the idea of transformation, feeling that UCT's hand is being forced, that their points of view [laughing] haven't, been heard. Which of course I feel is ridiculous, but that's not what I would say -I hope that doesn't, say anything about [laughing] the quality of my white friends, but ... you can't stop the people you went to undergrad with."

Drawing on developing counter-discourses, participants demonstrated a critical awareness of whiteness not demonstrated through other discursive sets. Participants argued for white people to listen and follow rather than lead transformation, as "if the issue affects black people, they know best how to fix it" (Mary, FG2), expressing a desire to reform Eurocentric university curricula, as "We have this unique opportunity to learn about Africa in Africa" (Hannah, FG1) and designating a role for themselves in activism, as "white voices can be very loud in white communities, without taking up black space" (Matt, FG1). This consciousness seemed to allow for imagination of new ways of constructing and performing whiteness in the context of transformation at UCT and in practice, seems to promote action aimed at reconceptualising the role of white people in South Africa within overall racial justice. However, this consciousness also has the potential to become an end within itself, discursively fracturing whiteness to preserve a more positive white identity, rather than interrogating, negotiating and re-imagining it.

Conclusion

The events of 2015 brought awareness once again to the noted gap between the adoption of transformation policies and their practical success in addressing racial inequality. This may be related to the interpretation and use of non-racialism in transformation and the discursive maintenance of whiteness, and additionally, how non-racialism is understood and used by white South Africans to aid or impede transformation efforts in higher education.

Participants' talk of transformation at UCT was largely grouped around three discursive sets of Old Order Whiteness, Defensive Rainbowism, and a developing set of counter-discourses. Understanding discourses as cultural resources, which interact with the construction of reality according to their relationships with power, subjectivity, history and material reality (Willig, 2008), allowed some understanding of how these sets function in relation to higher education transformation.

Old Order Whiteness drew on colonial discourse to normalise and justify a system of whiteness, with racialised beliefs voiced in "non-racial" terms, or colonial "logic". Defensive Rainbowism drew on liberal discourses to construct non-racialism as "colour-blindness", positioning participants as "born-free" or victims of "reverse racism".

Both uses of "non-racialism" conveyed only shallow non-racialism, without structural change (Delgado & Stefancic, 2012). Participants' uses of available discourse also reflected a construction and normalisation of a more positive identity, and a distancing from a more negative white identity. Consistent with the ideology from which each discourse originated, in Old Order Whiteness, a construction of a white "winner" identity was favoured over a white "oppressor" identity, and in Defensive Rainbowism, a "born-free", "victim", or "non-racial" identity was favoured over a more historically- and structurally-situated white racial identity. When drawn on, such constructions allowed participants to distance themselves from the negative connotations of whiteness. This seemed to restrict participants' consideration of race and transformation, and to prompt their opposition or apathy to forms of systemic racial transformation.

Another point of interest is the way in which discourses of emotion functioned in each discursive set to protect favoured constructions of whiteness. Drawing on Old Order Whiteness, emotionality was unfavourably constructed by participants in opposition to rationality, and this was used to undermine both women and black students, demonstrating the power held at the intersection of white and patriarchal discourse. Despite this, the same emotionality was used by white students in drawing on newer discourses of Defensive Rainbowism, where it functioned rather to describe and centre perceived white victimisation and anger. The use of this emotional discourse both to delegitimise black students' concerns and to legitimise those of white students seems to demonstrate how whiteness can adapt to preserve itself in changing discursive and ideological environments.

Due in part to the student protest climate, these discourses were also challenged by several participants. Those who expressed disillusionment with Old Order Whiteness and Defensive Rainbowism seemed actively to search for new ways to understand the calls of black students and other phenomena that these discourses had comfortably explained, bringing whiteness to greater visibility. New explanatory frameworks were tested by participants as to how they could challenge "white talk" and instead discursively construct new ways to be white, which could address the grievances raised by their black peers and the research before them. The cognitive labour was fairly clear in constructing these arguments, and emotion was also alluded to in ways somewhat different to other discursive sets. Students extended a slightly broader emotionality to the question of racism as one of overall justice, expressing frustration with the slow pace of transformation, whiteness, and racism, as well as disillusionment with shallow non-racialism, rather than selectively concentrating on white victimhood. Moreover, this engagement seemed to prompt their own calls for a reconstruction of non-racialism as a point at which race becomes structurally irrelevant, thus understood as a deeper goal requiring black students' empowerment and the disruption of institutional whiteness.

In addition, students highlighted roles that white students could take up in supporting transformation and addressing whiteness. A discursive fracturing was evident, whereby a "better" whiteness was contemplated in response to this grappling with "bad" whiteness. In these discourses too was evidence of a potential for constructions that favoured an adoption of a more positive white identity and a distancing from a negative white identity over the broader, inclusive "disruption" and re-imagination of whiteness. This was evident in participants' spoken thoughts on addressing racism in white circles, and also in what was said and unsaid regarding their inclusion in whiteness. As such, while there is potential for these newer counter-discourses to pave the way for new constructions and discourses of whiteness, they would perhaps require the further development of a white emotionality and reflexivity to serve as a foundation for facilitating deeper change.

Nevertheless, the challenging of dominant discourses highlighted an effort to look beyond the shaping lens of whiteness to consider transformation within a context of systemic racial inequality, and a developing imagination of active ways to "disrupt" whiteness. It is not clear how far this would practically extend, or to what extent it is represented in a larger white population. These findings are therefore to be taken in their context, of a small and limited cohort of white university students experiencing a concurrency of disruptive activism in social, academic, and online spheres. Still, they demonstrate a discursive negotiation and fracturing within this white South African student sample. The differing ways in which students understood or attempted to understand their whiteness in relation to the broader picture of South African racial transformation has developing implications for the future. It remains to be seen how this dissenting white support for social change will develop and influence the unfolding negotiation of transformation. It is clear though that whiteness at UCT has been somewhat shaken, disrupting students' dependence on comfortable discourses and potentially making way for new discursive constructions of reality.

References

Ahmed, S (2004) Declarations of whiteness: The non-performativity of anti-racism. Borderlands, 3(2). http://www.borderlands.net.au/vol3no22004/ahmeddeclarations.htm [ Links ]

Anciano-White, F & Selemani, J A (2012) Rethinking non-racialism: Reflections of a selection of South African leaders. Politikon: South African Journal of Political Studies, 39(1), 149-169. [ Links ]

Arribas-Ayllon, M & Walkerdine, V (2007) Foucauldian discourse analysis, in Willig, C & Stainton-Rogers, W (eds) The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Ashcroft, B, Griffiths, G & Tiffin, H (2001) Key concepts in post-colonial studies. London: Taylor & Francis (1998). [ Links ]

Bangeni, B & Kapp, R (2005) Identities in transition: Shifting conceptions of home among "black" South African university students. African Studies Review, 48(3), 1-19. [ Links ]

Baloyi, B & Isaacs, G (2015) South Africa's 'fees must fall' protests are about more than tuition costs. http://edition.cnn.com/2015/10/27/africa/fees-must-fall-student-protest-south-africa-explainer [ Links ]

Bass, O, Erwin, K, Kinners, A, & Maré, G (2012) The possibilities of researching non-racialism: Reflections on racialism in South Africa. Politikon: South African Journal of Political Studies, 39(1), 29-40. [ Links ]

Bester, J (2015) Protestors throw poo on Rhodes statue. http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/western-cape/protesters-throw-poo-on-rhodes-statue-1829526 [ Links ]

Biko, S (1987) I write what I like: A selection of his writings. Oxford: Heinemann (1978). [ Links ]

Crenshaw, K (1995) Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color, in Crenshaw, K, Gotanda, N, Peller, G, & Thomas, K (eds) Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement. New York: The New Press. [ Links ]

Cronin, J (1999) A Luta Dis-continua? The TRC Final Report and the Nation Building Project. Paper presented at the Wits History Workshop, Johannesburg, South Africa. http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/7764 [ Links ]

Delgado, R & Stefancic, J (2012) Critical race theory: An introduction. New York: New York University Press (2001). [ Links ]

Department of Education (1997) Education white paper 3: A programme for the transformation of higher education. Pretoria: Department of Education. [ Links ]

DiAngelo, R (2011) White fragility. The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(3), 54-70. [ Links ]

Dolby, N (2001) White fright: The politics of white youth identity in South Africa. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 22(1), 5-17. [ Links ]

Dubow, S (1995) Scientific racism in modern South Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dyer, R (2005) The matter of whiteness, in Rothenberg, P (ed) White privilege: Essential readings on the other side of racism. 2nd edition. New York: Worth Publishers. [ Links ]

Erasmus, Z & De Wet, J (2003) Not naming 'race': Some medical students' experiences and perceptions of 'race' and racism at the Health Sciences faculty of the University of Cape Town. Cape Town: Intercultural and Diversity Studies of Southern Africa, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Foucault, M (2002) The archaeology of knowledge. New York: Routledge Classics (1969-French). [ Links ]

Frankenberg, R (1993) White women, race matters: The social construction of whiteness. Minneapolis, Mn: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Green, M J, Sonn, C C, & Matsebula, J (2007) Reviewing whiteness: Theory, research, and possibilities. South African Journal of Psychology, 37(3), 389-419. [ Links ]

Hartmann, D, Gerteis, J, & Croll, P R (2009) An empirical assessment of whiteness theory: Hidden from how many? Social Problems, 56(3), 403-424. [ Links ]

Higham, R (2012) Place, race and exclusion: University student voices in post-apartheid South Africa. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(5), 485-501. [ Links ]

Higher Education Act 101 of 1997 (1997) http://www.unisa.ac.za/contents/projects/docs/Higher%20Education%20act%20of%201997.pdf [ Links ]

Hook, D (2001) Discourse, knowledge, materiality, history: Foucault and discourse analysis. Theory and Psychology, 11(4), 521-547. [ Links ]

Kessi, S & Cornell, J (2015) Coming to UCT: Black students, transformation and discourses of race. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 3(2), 1-16. [ Links ]

Koen, J & Durrheim, K (2009) A naturalistic observational study of informal segregation: Seating patterns in lectures. Environment and Behavior, 42(4), 448-468. [ Links ]

Loubriel, J (2016) 4 ways white people can process their emotions without bringing the white tears. Date accessed: 30 January 2018 https://everydayfeminism.com/2016/02/white-people-emotions-tears/ [ Links ]

Mandela, N (1994, May 10) Statement of Nelson Mandela at his inauguration as president. http://www.anc.org.za/show.php?id=3132 [ Links ]

Operario, D & Fiske, S T (1998) Racism equals power plus prejudice: A social psychological equation for racial oppression, in Eberhardt, J & Fiske, S T (eds) Confronting racism: The problem and the response. Thousand Oaks, Ca: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Ramsamy, E (2007) Between non-racialism and multiculturalism: Indian identity and nation building in South Africa. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 98(4), 468-481. [ Links ]

Rhodes Must Fall (2015, April 11). Press statement: Statement read out before the removal of the statue. http://rhodesmustfall.co.za/?p=92 [ Links ]

Schrieff, L E, Tredoux, C G, Finchilescu, G, & Dixon, J A (2010) Understanding the seating patterns in a residence dining hall: A longitudinal study of intergroup contact. South African Journal of Psychology, 40(1), 5-17. [ Links ]

Soudien, C, Michaels, W, Mthembi-Mahanyele, S, Nkomo, M, Nyanda, G, Nyoka, N, Seepe, S, Shisana, O & Villa-Vicencio, C (2008, November 30) Report of the Ministerial Committee on Transformation and Social Cohesion and the Elimination of Discrimination in Public Higher Education Institutions. https://www.cput.ac.za/storage/services/transformation/ministerial report transformation social cohesion.pdf [ Links ]

South African Constitution (1996). http://www.constitutionalcourt.org.za/site/theconstitution/english-2013.pdf [ Links ]

South African Institute of Race Relations [IRR] (2015) Born free but still in chains: South Africa's first post-apartheid generation. Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations. http://irr.org.za/reports-and-publications/occasional-reports/files/irr-report-2013-born-free-but-still-in-chains-april-2015.pdf [ Links ]

Steyn, M (2001) "Whiteness just isn't what it used to be": White identity in a changing South Africa. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Steyn, M & Foster, D (2008) Repertoires for talking white: Resistant whiteness in post-apartheid South Africa. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(1), 25-51. [ Links ]

Steyn, M & Van Zyl, M (2001) "Like that statue at Jammie stairs": Some student perceptions and experiences of institutional culture at the University of Cape Town in 1999. Cape Town: Intercultural and Diversity Studies of Southern Africa, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Suransky, C & van der Merwe, J C (2016) Transcending apartheid in higher education: Transforming an institutional culture. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 19(3), 1-21. [ Links ]

Suttner, R (2012) Understanding non-racialism as an emancipatory concept in South Africa. Theoria, 59(130), 22-41. [ Links ]

Taylor, R (2012) Deepening non-racialism in South Africa. Politikon: South African Journal of Political Studies, 39(1), 41-51. [ Links ]

Wale, K & Foster, D (2007) Investing in discourses of poverty and development: How white wealthy South Africans mobilise meaning to maintain privilege. South African Review of Sociology, 38(1), 45-69. [ Links ]

White Privilege Project (2015) Description ['About' section of Facebook page]. https://www.facebook.com/pages/UCT-The-White-Privilege-Project/1562888517320865?sk=info&tab=page info [ Links ]

Wiggins, S & Riley, S (2010) Discourse analysis, in Forrester, M A (ed) Doing qualitative research in psychology: A practical guide. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Willig, C (2008) Introducing qualitative research in psychology. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. [ Links ]

1 "Black" is used to refer to all groups classified as "non-white" under apartheid laws, namely, black, coloured, Indian, and Chinese groups.

2 UCT (nd) Transformation at UCT. http://www.uct.ac.za/main/explore-uct/transformation. Date retrieved: 20 June 2015