Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Psychology in Society

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8708

versión impresa ISSN 1015-6046

PINS no.55 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8708/2017/n55a6

ARTICLES

Mapping the black queer geography of Johannesburg's lesbian women through narrative

Hugo Canham

Department of Psychology University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg

ABSTRACT

To be black, working class, living in a township and lesbian is to be a discordant body. This is a markedly different experience than being a socio-economically privileged resident of Johannesburg. This paper sets out to map marginalised sexualities onto existing social fissures emerging out of South Africa's divided history of apartheid. It argues that while the repeal of the Sexual Offences Act, 1957 (Act No. 23 of 1957, previously the Immorality Act, 1927) and the promulgation of the Civil Union Bill (2006) has had a liberating effect on the lesbian community of Johannesburg; the occupation of physical space is deeply informed by the intersecting confluence of race, class, age, sexuality, and place. Based on the stories of black lesbian women, the paper analyses the occupation of the city's social spaces to map the differential access to lesbian rights and exposure to prejudice and violence. Findings suggest that their agential movement through space and performances of resistance lends a nuance to the dominant script of victimhood. Their narratives of becoming are shaped by the spaces that they inhabit in both liberating and disempowering ways.

Keywords: narrative maps, queer geographies, Johannesburg Pride, intersectionality, space

Introduction

This paper seeks to enliven the stories of five young black and lesbian identifying women in their early twenties and three older lesbian women in their early to mid-forties as they negotiate and constitute the queer geography of Johannesburg. By queer geography, I refer to a confusing, non-conforming, elusive, strange, and boundless geography that emerges and ebbs in unexpected spaces and ways. While Visser (2003), Elder (2005), Tucker (2009), and Rink (2013) have studied the queer geography of Cape Town, less work has gone into understanding Johannesburg as a city inhabited by lesbian identifying persons (Matebeni, 2008; Craven, 2011). I posit that relative to Cape Town's more organised queer geography, Johannesburg can be seen as having a less conforming and more elusive queer map. I am concerned with the ways in which everyday life acts of occupying and navigating contested spaces constitute the space. For this analysis, I rely on Lefebvre's theorisation of social space. I engage the queer orientation of Johannesburg through the stories of black lesbian women. Their narrative accounts and movements illustrate that they do not always play by given rules and they challenge the programmed consumption which has come to mark everyday life (Lefebvre, 2008). I access these insights through gathering their stories in order to voice the everyday experiences of otherwise marginalised women.

Following Atkinson (1997), I illustrate that stories provide a sense of rootedness, connect individuals to each other and give direction while also validating experiences that might not otherwise be considered significant. I centre narrative as it allows for an engagement with whole lives and it helps us make meaning of our stories to ourselves and others (Vincent, 2015). Narrative analysis and the study of space align around the unlimited multiplicity of meanings and possibilities which can emerge. Here, I borrow from Reissman (2008) who offers that narrative aims to convince others who were not present, that something happened. Moreover, this study is informed by the understanding that individuals use narratives to live in the present in relation to possibilities enabled by both their past and future. According to Andrews, Squire and Tamboukou (2013: 12), narratives consist of "reconstructions of pasts by the new 'presents', and the projection of the present into future imaginings". Therefore, while the present is of particular interest to this study, there is an acute awareness of the centrality of the past and future for understanding the present.

Background

I position the history of black and white lesbian and gay South Africans against the backdrop of the chasm of racialised class difference enabled by colonialism and apartheid. Being black meant that one was worse off than a white person on practically every index of life (Duncan et al, 2014). Apartheid spatial planning meant that black bodies lived parallel and distinct lives in black townships while white people lived in relative luxury and safety in white enclaves (Stevens et al, 2013). White and black interactions were therefore governed and enforced by systematic inequality (Canham & Williams, 2017). In the context of this inequality, the place of the city of Johannesburg as the leading location of economic dynamism, social life, migrant labour, and change has been well documented (Mbembe & Nuttall, 2004; Mbembe et al, 2004; Chipkin, 2008; Matebeni, 2011; Gevisser, 2014). And yet, notwithstanding the racialised fissures of the city, the end of formalised apartheid saw strengthened coalitions particularly in relation to the black and white LGBTI struggle. The first Johannesburg Pride was a seminal occasion for the demonstration of this solidarity but as we will see, this solidarity was short lived.

Method

I begin with a note about my experiences with conducting this research. In attempting to source the sample of interviewees, I encountered a crisis of legitimacy. While the challenge of finding participants initially surprised me, with hindsight, I have come to understand that the lesbian community has sound reason to be suspicious of black male cisgender researchers. In South Africa, Black males largely remain the greatest threat to their sense of safety (Jewkes et al, 2010). My identity positioned me as an outsider to the sample population. I am not certain if my explanations that I was an ally researcher were sufficiently convincing. I have however learned acute lessons in gathering the stories of the participants. Chief amongst these is the caution by Matebeni (2008) that research on South African black lesbian women has tended towards treating them as hapless victims. In accessing their life stories, I wanted to create space for both agential stories and those of victimisation, happiness and pain and their in-betweens. Narrative methods were most appropriate for this kind of research as it enabled the complexity of life to come to light. While Matebeni (2011) writes on the challenges of researching as an "insider", I highlight the difficulty of writing as an "outsider".

The interviews were simultaneously difficult and easy. They were difficult because I had to negotiate my outsider status by explaining myself in relation to who I am and what was my interest in the lives of lesbian women. However, because our lives are stories and we have a human impulse towards narrating our stories, participants were able to tell their stories within a context of respectful listening by an ally. There was a recognition that I was interested in more than their sexual identities but in their life stories of which sexual orientation is only but a part.

The final sample size is in part a function of my difficulty in sourcing black lesbian women interviewees. Interviews were conducted in English although they were interspersed with Nguni languages. I decided against including gay males because I believe that while there is great overlap in the lived experience of black gay men and lesbian women, there are qualitative differences. The literature (for example, Craven, 2011) suggests that black lesbian women's lives are more at risk than gay men. Munt (1995), Rothenburg (1995), and Matebeni (2008) argue that unlike gay men, lesbian women are less attached to place in that they do not as readily mark space as theirs. I wanted to honour this difference and through their narratives, explore how their social lives are structured by their sense of safety, place and beyond an "at risk" narrative. Moreover, I wanted to resist using the dominating gay lens (Matebeni, 2008) by focusing exclusively on a lesbian narrative. I finally sourced a sample of eight black lesbian women. I accessed the younger sample through university student lesbian and gay networks. The older sample was accessed through purposive sampling and snowballing enabled through referrals.

All eight of the women that constitute the sample reside in Johannesburg. At the time of the data collection, the younger women, all in their early twenties were university students of working class backgrounds although they themselves were of a class in the liminal space occupied by most students who may be about to embark on a transition from their parents' class to possibly becoming middle class. The five young women were all currently exploring Johannesburg's night life and dating. None of them had children. The three older women were all formally employed and middle class although their families of origin were working class. The older women were all in long term monogamous relationships with two of them married to their partners. They moved between suburbia, township, and rural life. All three have children. This provides a cross section of different life experiences lived in convergent and divergent parts of Johannesburg. The age difference between the two groups of women provides an opportunity to take a longitudinal view of the lives of black lesbian women, spanning the early 1990s to the present. To preserve the confidentiality of participants, pseudonyms are used in place of their names.

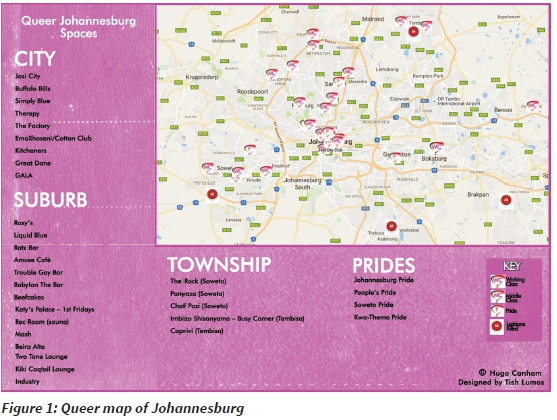

Since the importance of place is central to my thinking about identity, narrative and temporality, I found myself increasingly drawn to the map of Johannesburg and its nether regions. In order to productively hold both the stories of lesbian life and place, I began a process of superimposing these narratives onto the map of Johannesburg so as to understand their mutual co-construction for the participants. To give texture to the social spaces described by participants, I visited various night clubs and bars. In the analysis of the data, I tried to read both the interviews and map as narratives with the view of creating a new map that simultaneously tells the stories of black lesbian lives and recreates the map with beacons of joy and sadness in their everyday lives. My articulation of a narrative map is both literal and figurative. It is figurative to the extent that it is interested in mapping lives that are generally unknown. My interest is literal because I am interested in the actual map of Johannesburg not as a passive receptacle but as productive (Lefebvre, 2008). Stated differently, I explore the narratives of black lesbian women in their production of space. When compared to Cape Town, South Africa's "gay capital" (Rink, 2013), Johannesburg does not have a queer map. While it is not necessarily desirable to have a queer map for the capital driven tourist visibility of lesbian and gay spaces, it is a politically significant act to draw this map (see figure 1) as a form of voicing presence of marginal bodies and as an agential exercise of claiming and producing space. I position this endeavour as a starkly different one to that of the highly commercialised Pink Map of Cape Town which Rink (2013: 72) has described as having moved from "sexual to consumer citizenship as a means of belonging".

According to Billington et al (1998: 113), "[W]e can only know ourselves and our environment through the maps or metaphors our society makes available to us". In response, I agree but pose the question of what happens when the maps made available are inadequate and do not take certain bodies into account? Figure 1 is one attempt to engage in a conversation about how queer bodies orient themselves in a city that they fashion for themselves. This map is of course limited. For Lefebvre (2007), no amount of maps can capture the complexity of space or decode all its meanings. With the stories of lesbian women, I attempt to dismantle a heteronormative reading of space and reconstruct it with a queer trace in a manner recognisable to them. The map also contains commemorative markers of where black lesbian women have been reportedly murdered in hate crimes. Aversion of this map is live on google maps (www.goo.gl/iOZl6u) for queer citizens to engage and reorient themselves as members of a queer city. This map is deliberately positioned as queer and not lesbian as spaces are occupied fluidly. Moreover, in consideration of Matebeni's (2008) insight that lesbian women are generally less invested in owning space, the map does not single out spaces that are "lesbian". The "ephemeral nature of lesbian social space" (Rink, 2013: 78) should however be read together with the view that gender based socio-economic inequality means that some lesbian women are economically inhibited in their access to commercialised space (Rothenburg, 1995), and socially circumscribed by gender based violence.

The narrative arcs of queer movements

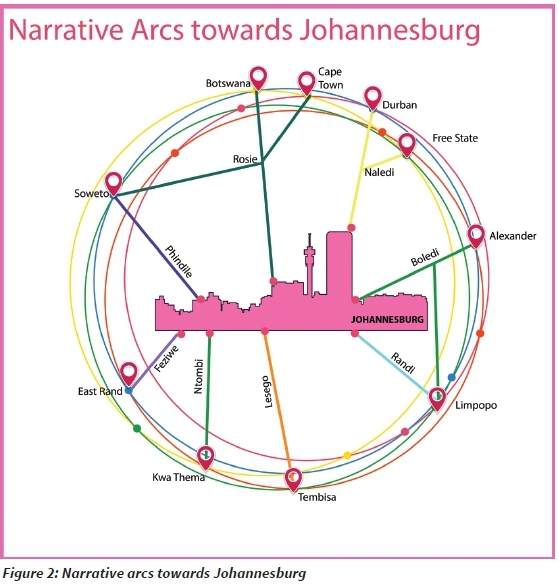

Four of the women that were interviewed grew up in neighbouring provinces and the other half were raised in townships around Johannesburg and Ekurhuleni. All now move within the inner parts of Johannesburg, either through living there or commuting from the surrounding townships to study, work and socialise. There is therefore a narrative arc in the stories about movement. The stories cross multiple geographic spaces converging inwards towards the city. For some, the movement to Johannesburg also comes with a class transition from working class backgrounds to lower middle class or middle class positions.

I term these narrative arcs "queer movements" because they also come with a fuller realisation of a queer identity. This identity was often not possible in generally more homophobic places of origin such as townships or rural homelands where families resided. At another level, there are movements between spaces within the city and its surrounding townships. These movements are enabled and restricted by race, class, gender and sexual orientation. I trace these narrative arcs in the stories of the women interviewed.

Although Naledi (gender activist) has resided in Johannesburg for nearly six years, her stay in Johannesburg is the least secure as she is on secondment from her job in her home province. She maintains a split site existence between Johannesburg where she resides, her home province, and another province where her partner lives. Her stories traverse these multiple sites and temporalities. Reading Naledi's story without paying attention to the networks and pathways of spaces that she inhabits (three provinces, rural-urban) is to understand space in abstraction. In this regard, Lefebvre (2007: 86) argues that "social spaces interpenetrate one another and/or superimpose themselves upon one another". Focusing on Johannesburg is therefore a limitation.

Compared to the rest of the sample, her story is atypical because she only began exploring her lesbian identity in her late 30s after she raised two young adult children. Growing up in a small town with no point of reference for her feelings, she notes:

"I knew about my feelings. But growing up in a small town, you tend not to understand.

And you feel oddthatyouare attracted to a girl. And you think it's something that is not normal, unusual. So I suppressed my feelings."

Her move to Johannesburg has not totally freed her however, as she believes that she works for a conservative organisation and hercareerwould end if they found outthatshe is lesbian, despite the fact that she is employed as a gender activist. Her assessment of her patriarchal workplace leads her to dissociate from performing her sexual orientation.

"It will be the end of my career I'm sure. Our executive structures are male dominated, and there's a little bit of resistance, in terms of that."

However, despite her fears and non-participation in the Johannesburg LGBTI community, bars and nightclubs, and Pride, she believes that she is happiest when in Johannesburg. Pile (2009) advises that particular emotions and affect are enabled by geographical location. Like Wetherell (2012), for Pile (2009), emotions are both personal and social and not reducible to one of the other.

"And I'm more happy here than ever before. I don't think that if I was still back home I would have been me."

Naledi is simultaneously inhibited and at her freest in Johannesburg. She inhabits the city with ambivalence where she is both in awe of the freedom to be herself while continuously aware of homophobic gazes. She was surprised by the interrogating stares that she and her masculine presenting partner were exposed to in a supposedly safe urban space like a Johannesburg mall.

"The other time we were at Eastgate, doing shopping and both of us didn't expect that this could happen in Joburg. And there were people looking at us, it's like they were seeing ...I don't know what."

Johannesburg is thus a paradoxical space (Pile, 2002). Like Naledi, Rosie and Boledi are older participants. Boledi's (health worker) and Rosie's (information technology, IT) stories move across space and these movements coincide with apartheid spatial planning and violence. For instance, as a young child, township violence in Alexandra (Johannesburg) and the state of emergency compelled Boledi's parents to send her to Limpopo where she lived with her grandparents. As a consequence of riots in Soweto, Rosie's family moved her to Botswana where she finished high school. While both were born in Johannesburg in the 1970s, they were raised in various parts of the country. They however came of age in Johannesburg and participated in the nightlife social scene in the 1990s and early 2000s. Their recollections suggest that women's vulnerability to violence in the city is not a new phenomenon (Gqola, 2015). As a function of safety, being older and having wives and children, they no longer frequent lesbian women's nightclubs.

Boledi: "We buy a bottle of wine, drinkin the house. Going to Busy Corner in Tembisa is not worth the risk of being violated or hi-jacked."

Rosie: "Now we have a baby. Ja, so it's more about inviting people over or going to their house type of thing. There are certain places that you just ...I wouldn't go to."

Of the three older interviewees that are all in their 40s, two are married to women. This suggests that the progressive LGBTI legislation is enabling a new narrative for lesbian women. This narrative includes victimisation but also enlarges their lives and possibilities for happiness. Their class position shields them from the brazen homophobia that working class lesbian women experience. Breaking away from resistant cultures and religion, some have begun to create new traditions such as creating new surnames with their wives and children.

Boledi: "Before the marriage act was legalized, we had already changed our surnames because our issue was that our parents were so uncomfortable with this gayness."

To honour each other and to protect their partners from each other's families, the two married couples have entered into protective contracts.

Boledi: "We protected ourselves against our families because we had observed how other lesbians' families came and took everything when they died."

All three of the older participants recounted pressure to date men when they were younger and some of their children were born out of these relationships. Rosie articulated this by saying:

"You try to live according to what society expects of you, and dated boys in the beginning."

Two of the younger women were born in Johannesburg and the other two moved to the city to study at the local universities. The narratives of all eight participants traverse multiple spaces including other provinces. This is diagrammatically represented in figure 2. However, in this paper, I focus on those parts that engage the city. This leads to the problem of "narrative excess" - a term that I take from Michelle Fine (2015) to point to that which is left out of life accounts in research work.

Mapping Johannesburg Pride and resistance

For the young lesbian women interviewed in this study, the Pride march emerged as a safe space but with qualifiers. The five student participants attended the Pride marches. For Lesego and Feziwe (both students), Pride is about mutual affirmation and highlighting the plight of gays and lesbians.

Lesego: "I feel that it's about gays and lesbians supporting each other. Sometimes you feel alone and need support just coming out and accepting who you are and for people to accept us for who we are. It's to stop the attacks against gays and lesbians - that's what I think the Pride is about being proud of who you are."

Feziwe: "So I feel that Pride should focus on bringing a spotlight on those issues instead of us all just prancing around feeling ... happy."

These young women come to participate in Pride in the present against a history which I map here. In this study, Johannesburg Pride serves as a site to explore a number of interests chief amongst which is the relationship between geography, emotions and identity. Ahmed (2004) and Held (2015) posit that a clear mutually constitutive relationship exists between these concepts. Here, emotions transcend interiority to illustrate their production in the interplay between and among people and geography. The first Johannesburg Pride march occurred on the eve of democracy in 1990 and was characterised by an affective exuberance influenced by the looming political changes and the release of Nelson Mandela and other political prisoners. The seminal organising role of GLOW (Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand) led by Simon Nkoli, Bev Ditsie and others meant that black voices and presence were influential in organising the event. Describing the inaugural Pride in 1990 in an interview, Bev Ditsie (2013) states:

"Those who were there, and there aren't many, remember the fear, the excitement, and the euphoria of it all. We had been vilified and made to feel so ashamed for so long. Just the idea of being out in the sun, reclaiming our God given right to exist was a thrill I will probably never feel again. ...I think that day signalled the beginning of my personal liberation and my political education".

In subsequent years, the shift in ideology from politics to commercialisation have thrown sexuality, class and race fissures into sharp relief. Commentators have remarked that Pride has been primarily organised by wealthy white gay men which were later joined by white lesbian women (Craven, 2011). This has marginalised the participation of working class black people and black lesbian women in particular. The emergence of Nkateko and FEW (Forum for the Empowerment of Women) which were formed to advance the rights of black lesbian women, is an indication of the exclusionary nature of mainstream LGBTI organising in Johannesburg and South Africa more broadly.

For black lesbian women, the oppressions are significantly increased by their gender identity as women who are routinely at risk of gender based violence including rape (Gqola, 2015). Facing the possibility of being gang raped after participating in the inaugural Pride march in Johannesburg, Ditsie (2002) from Simon and I notes:

"Gender-based violence is a problem in South Africa, but coming out as lesbian is even harder because then you are putting yourself in the firing line."

In 2012, twenty-one years after the inaugural Pride in South Africa, the gendered and classed cleavages had widened so drastically that the gender rights feminist group "One in Nine", made up primarily of black queer activists, tookthe unprecedented step of disrupting the march in protest. Their actions of physically laying their bodies on the line (they lay across the street) were to momentarily halt the parade in order to mark a moment of silence (Davis, 2012). This was meant to commemorate the gruesome deaths of murdered black lesbian women in the townships of South Africa (see figure 1) and to re-politicise Joburg Pride. The disruption of the parade led to a raced and classed confrontation between the largely white paradersand the mostly black lesbian women and gender activists. Those being commemorated, who were raped and killed in reported hate crimes directed at lesbian women in townships, include Eudy Simelane, Girliy Nkosi, Nokuthula Radebe, Noxolo Nogwaza, Maleshwane Radebe, Duduzile Zozo, Patricia "Pat" Mashigo and others. Moffett (2014:219) has observed the escalating trend of "raping, beating, and even murdering black lesbians in townships". City Press' Charl Blignaut (19 December 2013) notes Zanele Muholi's characterisation of black lesbian women as follows: "crime scenes have come to landmark black lesbian identities". Muholi has represented this violence and resistance in the form of a "die in".

Reflecting on the events of Pride 2012, Phindile, a student, observes the class and race fractures in the LGBTI community:

"When the 2012 incident happened I realised that the people that were against honouring those who had been killed were people that were privileged. They were not worried about getting attacked or raped. It highlighted divisions of class and race. Most of the time, you find that people that are white or more privileged were inside the Pride fence and more black people were outside the fence and had to enter Pride from outside. So it was more outside looking in to the freedom."

Space does not give action free reign (Lefebvre, 2007). It can be made a capitalist commodity, thus controlling access. This is to say that the movement of working class lesbian women is constrained by the cost of accessing spaces such as Pride which are fenced off. They can be only accessed at a financial cost which is beyond the means of most working class black lesbian women. The moment of the confrontation at the parade re-inscribed the power asymmetries inherent in the relationship between privileged middle class and mostly white gay men and black disempowered lesbian women. Scenes captured on video show the white paraders threatening to walk over the activists. The physical threat of violence was accompanied by claims to space with calls for the protestors to "Go back to the location!" and "Drive over them" and "Get out of here!" (Davis, 2012; Ramkissoon, 2012). These claims to space and disciplining of black lesbian women's bodies for transgressing white wealthy spaces reveal the spatial mapping of gender, sexual orientation, race and class identity in Johannesburg.

It is clear from Randi, Ntombi and Phindile that not all Pride marches in Johannesburg are affirming. People's Pride is an alternative safe space and an example of queer agency created by black lesbian women and gender non-conforming persons in response to their exclusion from the corporatised Joburg Pride.

Lesego: "People's Pride came about after the 2012 incident. People wanted to take back Pride and make it political. It had become more of a parade than a march."

Randi: "... but People's Pride, there you feel, you can let go, you don't have to be anything else but yourself."

Ntombi highlights the importance of Soweto Pride for where (black) people live.

"The Soweto Pride, people felt like they needed something political to be happening in the township. People thought 'why don't we take Pride to a space where people live'."

Racial fissures in LGBTI representations are apparent in the student narratives.

Ntombi: "Joburg Pride, people felt it was elitist and very, very racial. The first time I ever went to Pride and I said 'hey guys I am going to Pride'and they said, 'willyou be at a black Pride or a white Pride'"?

Phindile: "Oh and I don't go to Joburg Pride now, I only go to People's Pride."

If Pride is meant to be a celebratory carnival, the killjoys are black lesbian women without a sense of humour. Ahmed (2010: 67) notes that, "within feminism, some bodies more than others can be attributed as the cause of unhappiness". Ahmed joins Lorde (1984) and hooks (2000), when she evokes the figure of the angry black woman whose very presence can lead to an affective conversion. If black women want to participate in the Pride parade, it must be on the terms of the dominant group which wants to portray a singular narrative of happiness to match the advertiser's expectations (Rink, 2013). Corporate brands look for narratives of positive associations and celebration rather than unhappiness and protest (Thompson, 1990). The very language of naming Pride as either a march or a parade is illuminating. A march signifies protest and unhappiness while a parade is characterised by celebration, lightness and happiness. "White Pride" is a corporate celebration and "black Pride" is mourning, joy and struggle. Celebration and protest.

Ntombi differentiates between black Pride and white Pride as follows:

"Black Pride is where all the black lesbians sit outside and drink. White Pride is inside the fence where you have to buy drinks and you have to listen to music that you are not used to listening to."

In this characterisation, white Pride is characterised as exclusionary of working class lesbian women in terms of the price of access, drinks and geography.

With the gains made to recognise the legal rights (including civil unions) of LGBTI South Africans, middle class LGBTI communities have much to celebrate. The murder of poor black lesbian women living in townships and informal settlements suggests that this group has less to celebrate. In this context, living in the same city and country does not guarantee equal human rights, bodily integrity and safety. Randi struggles to reconcile the progressive legislation of civil unions with the violence that black lesbian women live with. Johannesburg Pride captures this contradiction for her, as follows:

"I just don't think we have anything, I mean marriage, nahl I can marry another woman but it's also okay, I can get killed and no one gets arrested."

Intersectionality and the production of "dirty lesbians"

Held (2015: 40) has demonstrated that "comfort and safety are emotional states that are classed, racialised, gendered, and sexualised". The recognition ofvaryingsocial identities in relation to how they converge with different consequences for different people is important for understanding the lives of raced, classed and gendered identities. In Crenshaw's (1991) theorisation of intersectionality, gender has proven to be inextricable from race. The concept of intersectionality was a response to research that tended to focus on inequalities along the lines of either one of the categories of race, gender, or class (Acker, 2006). Gender identity and sexual orientation further complicate the ways in which we understand the world. The majority of black women are working class which means that they bear the brunt of triple oppression (De La Rey, 1997) with the added burden of economic marginalisation. Disadvantage is increased for working class black lesbian women as they cope with additional prejudices targeting lesbian women. In recognition of the racialised, classed and spatial divisions, the younger lesbian women used the word "dirty lesbian" to describe poor, black, township based lesbians. When something is considered dirty, there is something sexually enticing and simultaneously forbidden about it. It however also signifies diminished value. Working class lesbians are colloquially known as "dirty lesbians". Soweto Pride is associated with "dirty lesbians" while Johannesburg Pride is elitist.

Ntombi: "Some gays will say, Iam not going there you know it is going to be ghetto and there will be dirty lesbians and dirty gays. So I will just wait for the Joburg Pride'."

Randi: "It's like you don't feel like you belong there, it's like it's our space but it's not yours, what are you doing here"?

Geography is an additional marker of difference as it often signals access to particular forms of social capital. As a global code, the pink map (Rink, 2013) has come to signify consumption. The use of space is marked by class differences. Middle class lesbian women and gay men socialise in suburbia while those from working class backgrounds hangout in the townships. Caricaturing these differences, Ntombi noted the following:

"I will hang around with these kinds of gays and we will go to Melville and the other people, they can stay in the township. The other so called "dirty gays" can stay there and they can date the riffraff in the townships."

Phindile attributes the term "dirty lesbian" to working class township lesbians:

"When they talk about a dirty lesbian they are talking about the township lesbian. So it would be that lesbian with dirty All Stars who doesn't comb their hair or has like dreadlocks and they aren't really well maintained."

Dirty lesbians disrupt and produce spaces that are out of joint but bear the heightened risk of discipline directed at non-conforming bodies. Once described as dirty, their trauma is not real and can be dismissed by mainstream society.

Randi: "I die and I get raped and I still see my rapist every day, my rapist passes by, everybody will see he's the one who raped me, I had evidence, but no one is arresting him because he raped a lesbian. I get to face my hell every day... He can come and do it again and again."

Queer production of space and tenuous bodies

Henri Lefebvre (2007) suggests that space is never neutral. In this regard he states that social space is produced by past actions, it enables the creation of fresh actions, while simultaneously prohibiting and suggesting others. For instance, apartheid race based segregation produces the present and enables resistance to new forms of inequality while simultaneously foreclosing access to safety. To comprehend everyday life, Lefebvre (2004) suggests that time and space should be thought of together and in a non-linear fashion. Thus, seeing the role of the past as enabling and limiting spatial access in the present is a useful lens through which to understand how lives are ordered. For Freeman (1993), the past lives on in the narrative unconscious to affectively influence the present in ways that we may be unaware of. In this conception, the idea of the self and that of history are mutually constitutive. Exclusionary histories therefore cannot be simply undone by legislative change and goodwill. The past constitutes the present and the parameters and possibilities of social space. For Lefebvre (2007: 77), "social space cannot be adequately accounted for either by nature or by its previous history". The production of social space is thus in dynamic tension between the past and its potentialities in the future based on present actions and possibilities.

"Gay friendly" spaces have proliferated in Johannesburg. However, like preceding decades, gay and lesbian night clubs are largely segregated along the lines of race and class. Working class members of the LGBTI community socialise in spaces that are accessible to public transportation (for example, Noord Taxi Rank and Park Station) which are largely located in downtown Johannesburg. Jozi City, Simply Blue, Buffalo Bills, EmaXhoseni, Great Dane, Kitcheners and Liquid Blue are examples of night clubs and bars frequented by black working class members of the lesbian and gay community. (Figure 1 presents this diagrammatically.)

Social space is racialised within the lesbian women's leisure scene.

Randi: "Even in a social space like Kitcheners or Great Dane ... it's either there's one white head within more black heads or there's one black head within more white heads."

Phindile: "I think it is about class. You go further North the more things get expensive and I mean most black people can't really say they are upper middle class or even middle class."

Randi: "So race is everywhere, especially in social spaces even with lesbians. Because white lesbians they will have their own corner, black lesbians our own corner, Soweto lesbians our own corner, Hillbrow lesbians our ghetto corner..."

With the migration of middle class whites out of the city towards Northern suburbia, old iconic bars and night clubs located in Hillbrow and Yeoville, such as Skyline, have been abandoned. Harrison Reef Hotel which had been the site of an LGBTI friendly church and entertainment place in the early nineties was negatively affected by this migration (Gevisser, 1995; Matebeni, 2011). The Heartlands experiment of creating a gay hub in Braamfontein succumbed to a similar fate. The white middle class lesbians and gays have moved further north of the city and can be found in Greenside, Sandton, Fourways and Pretoria together with a few members of the black lesbian and gay middle class. Even though the overlaps are class based, racial segregation of these social spaces is the dominant marker. The students capture these fissures as follows:

Ntombi: "Ja, there is also a race thing, I mean you hardly find white people at Open Closet except on first Friday of each month. At first Fridays. That happens in Fourways at a club and then they all go there."

Ntombi: "As black lesbians, we don't like going anywhere because we feel like we should be able to come back. I am black and I am lesbian and it's nota nice position to be in at 2am in the morning in an area that you are not really used to."

For older lesbian women such as Rosie and Boledi, spaces that are now no longer safe, such as Hillbrow, were the spaces where they explored their lesbian identity in the 1990s. Boledi provides an affective dimension to space when she describes frequenting Skyline as paradise:

Boledi: "It was paradise and made me believe I was okay. And then I started really having girlfriends."

Rosie: "I socialised in Melville, the Rock in Soweto, Time Square and Yeoville. It was a completely new world."

But violence was part of their narrative in their early years just as it is the story of younger lesbian women now.

Rosie: "Even back then we would hear of people's deaths in Meadowlands. We were part of the lesbian community, we would know that this is so and so's friend."

Specialised knowledges and safe spaces

Safety, space and class are intimately related and co-constitute each other. Lesbian women proactively fashion spaces that enhance their survival and safety. This resistant narrative is enabled by what Patricia Hill Collins (1990) calls "specialised knowledge" developed from a standpoint of being equal and not inferior. It enables people to strategise for safety. When asked about which places she experiences as safe Randi thinks for a minute before answering. Her answer however suggests that safety can be produced as a function of class and deliberately created in safe zones like GALA (Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action).

Randi: "When you're in Sandton, holding hands, forgetting everybody else exists. You can do that in Sandton. Not here, not in any school I think. And gay forums are safe, lesbian spaces and let's say GALA."

Sandton represents safety through its middle class policing of space and as an island of enforced tolerance. Black working class bodies are however only guests in that space as the cost of living and consuming there are prohibitive. Campuses are seen as dangerous places where lesbian women experience homophobia. Ntombi describes an experience as a first year student when she and her lesbian friends were suddenly disrupted by a bible wielding male student who told them that they were sinners:

Ntombi: "But we walked away feeling like wow, you know the nerve of this guy and I have to sit in class with him tomorrow and look at him."

Beca use they are not only victims, black lesbians continue to assert their identity and self-love. Even as these spaces are punitive, there are ways in which the presence of lesbian women opens them to other possibilities. This recalls Lefebvre's (2007:83) assertion that space is a set of relations, it "contains and dissimulates social relationships". It allows for contestations and the production of new social relations. This can be read in relation to Phindile who also recalled an experience when two male students from another African country accosted her and her lesbian friends on campus. The male students said that Phindile and her friends would have been killed if they were in their home country.

Phindile: "But we were able to talk back to them and tell them 'wellyou have come to our space now'."

Lesego: "I continue to be affectionate with my partner and I feel that I should be given the freedom and space to show affection like a straight person would."

For three student participants, GALA appears to transcend social difference and has been fashioned into a safe space for LGBTI persons. GALA can therefore be seen as a queer space that enhances safety, specialised knowledge, and self-love.

Randi: "So how do I explain GALA? It's like a personal heaven - your little space. And you find people who will not judge you at all... It brings meaning to who you are. I mean if it wasn't for GALA I wasn't going to know what the hell activism is and I wasn't going to feel the need to defend somebody or the need to march for something ..."

As an additional strategy for enhancing safety, Rosie proposes that moving in groups can be protective.

Rosie: "tf it's a whole group of you, it's kind of like okay."

Phindile and Lesego also avoid being alone and do not socialise in particular spaces. They prefer picnics and Braamfontein based nightclubs.

Phindile: "Even when I go out, I make sure I go with more than one person. Safety in numbers. I don't go downtown."

Lesego: "In Braamfontein, I would do anything and on campus. But in the CBDI would be cautious."

Socialising in groups allows lesbian women to protect each other from potential violence.

Ntombi: "And when they do go out to places like Caprivi or somewhere, they will go as a group and they will come back as a group. So they will make their own little space there and if they find that it is not accommodating, they leave."

Ntombi: "Because people are afraid of being identified as lesbian they hang around with each other. They will have maybe a lesbian party every two months at someone's house and then it moves."

The ephemeral and transient occupation of space articulated by Ntombi reinforces Rothenburg's (1995) assertion of lesbian women's non-territorial engagement with space. However, in addition to socio-economic precarity, safety appears a salient consideration as lesbian women appear less attached to particular spaces. Even as they feel freer in Johannesburg compared to their townships, Feziwe and Boledi challenge the notion of degrees of safety as follows:

Feziwe: "I feel this safety issue is not necessarily confined to specific places. It's everywhere - at the petrol station, or at school, just everywhere."

Boledi: "I feel unsafe most of the time, all the time. I feel unsafe as I drive out of there and when I join the road. I feel unsafe when I go shopping, there's that acute awareness that I am not safe. It's constantly there in the house at night. We have security guarding the complex, but it does not make me feel safe. On my pedestal, I have pepper spray. I have a machete under my bed. I used to have a gun."

However, despite her constant fear, she recognises that her class position shelters her from the exposure that her unemployed friends face. This highlights the value of an intersectional analysis that illustrates the fact that black lesbian women are not a homogenous group.

Boledi: "In the township, somebody can just break the door. I am a lot safer. There is an illusion of safety. I am able to buy property where there is a level of safety which is not available to somebody who is not working."

The sharp age distinctions characterised by the generational differences is an additional line of heterogeneity which influence notions of relative safety. It means that older lesbian women have taken to house gatherings while the younger members of this community enjoy the night club scene. This feature of the city suggests that friends of similar sexual orientation, gender identity and race frequently socialise at house parties. These private parties serve as spaces to network where safety and solidarity is established and mutual support and affirmation is given. House parties can therefore be seen as an additional way in which the spatial queering of the city occurs. This is understood in light of Hammack's (2010) observation that identities under threat tend to congregate in solidarity and mutual meaning making. However, despite there being a thriving township "gay scene" (De Waal & Manion,2006) in places like Soweto and Kwa-Thema, the threat of violence in townships is constant (Blignaut, 2013). Lesbian and gay working class youths move between spaces in the inner city and the townships along the public transport corridor based on emotional, financial, and physical accessibility. Their choices are more circumscribed than their middle class peers. Older lesbian women who now occupy a middle class habitus are however able to access the "good life" made possible by easier mobility, living in safer neighbourhoods, and accessing entertainment options that do not expose them to the levels of threat faced by younger working class lesbians.

The picture that we are left with is messy and points to the contradictions which are inherent in South African society. The complexity can be best read using an intersectional lens which heightens the salience of race, gender, sexuality, class, age, and geographic location. Space undergirds and gives shape to these differences and structures the possible performances of black lesbian identity. Here, space is understood in relation to Lefebvre's (2007: 73) injunction that space subsumes things and is the "outcome of a sequence and set of operations, and cannot be reduced to ... a simple object". Space is therefore not simply one of the intersecting influences but actively constitutes the effects of intersecting forces. The stories told by the lesbian women in this section suggest that safety is always contingent and ephemeral. Safe spaces are therefore not fixed as they are products of complex and relational flows of power.

Conclusion

I have highlighted five thematic arguments in orderto present the stories of a Johannesburg based group of black lesbian women. These areas of analysis were: narrative arcs of queer movements; mapping Johannesburg Pride and resistance narratives; intersectionality and the production of "dirty lesbians"; queer production of space and tenuous bodies and specialist knowledges and safe spaces. The analysis was framed by a keen interest in how spatiality simultaneously constrains and opens possibilities for productive life. Central to this was the role of narrative which enabled a nuanced intersectional renderingof the lives of this specific group of women. Based on this, I conclude that living as a black working class lesbian woman is an act of constant resistance to annihilation in a patriarchal anti-poor and anti-black heteronormative society. The stories of black lesbian women suggest that they are fully conscious of the spatially informed precarious position that they occupy as historically and potentially violated bodies. In this sense, they are victims. But because they live with agency to resist and craft their lives in various spaces, they are victors too. They performatively (Johnson, 2011) disrupt spaces even in the disjointed manner in which they occupy these. When mostly white and wealthy members of the LGBTI community annually celebrate the legislative freedoms of living in Johannesburg, working class, township-based black lesbian women point to the elision of their experience and the inequality between wealthy safe identities and their own disposable bodies. They opt for a People's Pride in the very same spaces where they are most likely to be violated such as townships and Hillbrow.

Alongside their transgressive performance of identities, they assert a pride and self-love that defies and re-appropriates terms such as "dirty lesbians". Conscious of their spatially informed vulnerability, they socialise where they gain strength in numbers. Ever aware that safety is always contingent, the lesbian women students create "safe zones" on campuses where they develop a critical consciousness (hooks, 1997) of their position. This enables them to critique the gaps between progressive legislation and their lived experience, the classed commercialisation of queer identities, as well as to forge solidarity with working class lesbian women. Black lesbian women draw on a history of black women's protest and struggle to create their own Pride - a People's Pride, Soweto Pride, Kwa-Thema Pride. They create multiple sites of sociality and resistance such as house parties, picnic gatherings, and accessible night clubs and thereby produce a narrative that centres localised marginalisation and sites of joy and resistance. Following Johnson (2011), in order to privilege their embodied experiences, they corporeally express themselves with the very bodies that are under threat. Their agential movement through space and performances of resistance lends a nuance to the dominant script of victimhood.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the women that told me their stories. I hope that the paper makes some contribution to queering the narrative map of the city and leaves a trace of the participants' stories. Tish Lumos translated my ideas into a visual representation. Thato pointed out my blind spots. The anonymous reviewers refined my thoughts and reading. Thank you.

References

Acker, J (2006) Inequality regimes gender, class, and race in organizations. Gender & society, 20(4), 441-464. [ Links ]

Ahmed, S (2004) Affective economies. Social Text, 22(2), 117-139. [ Links ]

Ahmed, S (2010) The promise of happiness. London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Andrews, M, Squire, C &Tamboukou, M (eds) (2013) Doing narrative research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Atkinson, P (1997) Narrative turn or blind alley. Qualitative Health Research, 7(3), 325-344. [ Links ]

Billington, R, Hockey, J, &Strawbridge, S (1998) Exploring self and society. Houndmills: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Blignaut, C (2013) Activists mourn another murdered lesbian. City Press. http://www.news24.com/Archives/City-Press/Activists-mourn-another-murdered-lesbian/20150429 [ Links ]

Canham, H & Williams, R (2017) Being black, middle class and the object of two gazes. Ethnicities, 17(1),23-46. [ Links ]

Chipkin, C (2008) Johannesburg transition: Architecture and society from 1950. Johannesburg: STE Publishers. [ Links ]

Collins, Hill, P (1990) Black feminist thought. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Craven, E (2011) Racial identity and racism in the gay and lesbian community in post-apartheid South Africa. Unpublished Masters dissertation. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, K (1991) Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6),1241-1299. [ Links ]

Davis, R (2012) Joburg Pride. A tale of two cities. Daily Maverick. http://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2012-10-09-joburg-pride-a-tale-of-two-cities/#.U8GEdPKMWSo. [ Links ]

De la Rey, C (1997) South African feminism, race and racism. Agenda, 13(32), 6-10. [ Links ]

De Waal, S & Manion, A (2006) Pride: Protest and celebration. Johannesburg: Jacana Media. [ Links ]

Ditsie, B P & Newman, N (2002) Simon and I. Documentary film. http://stepsforthefuture.co.za/video/simon/ [ Links ]

Duncan, N, Stevens, G &Canham, H (2014) Living through the legacy: The Apartheid Archive Project and the possibilities for psychosocial transformation. South African Journal of Psychology, 44(3), 282-291. [ Links ]

Elder, G (2005) Somewhere, over the rainbow: The invention of Cape Town as a "Gay destination", in Ouzgane, L& Morrell, R (eds) (2005) African masculinities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Fine, M (2015) Critical narrative excess: The existential weight of policy narratives gathered in times of neoliberal blues. Narrating lives and living stories in contexts of socio-political change symposium. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Freeman, M (1993) Rewriting the self: Memory, history, narrative. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gevisser, M (1995) A different fight for Freedom: A history of South African lesbian and gay organisation - the 1950s to the 1990s, in Gevisser, M & Cameron, E (eds) (1995) Defiant desire. Gay and lesbian lives in South Africa. New York & London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gevisser, M (2014) Lost and found in Johannesburg: A memoir. Johannesburg: Macmillan. [ Links ]

Gqola, P. D (2015) Rape: A South African nightmare. Johannesburg: MF Books. [ Links ]

Hammack, P (2010) The cultural psychology of Palestinian youth: A narrative approach. Culture & Psychology, 16(4), 507-537. [ Links ]

Held, N (2015) Comfortable and safe spaces? Gender, sexuality and 'race' in night-time leisure spaces. Emotion, space and society, 14,33-42. [ Links ]

hooks, b (1997) Performance practice as a site of opposition, in Ugwu, C (ed) (1997) Let's get it on: The politics of black performance, Seattle: Bay Publishers. [ Links ]

Jewkes, R, Sikweyiya, Y, Morreu, R, & Dunkle, K (2010) Why, when and how men rape: Understanding rape perpetration in South Africa. SA Crime Quarterly, (34), 23-31. [ Links ]

Johnson, E P (2011) Queer epistemologies: Theorizing the self from a writerly place called home. Biography, 34(3), 429-446. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H (2004) Rhythmanalysis. Space, time and everyday life (1992- French). London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H (2007) The production of space (1974-French). Maiden: Blackwell Publishing. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H (2008) Critique of everyday life. Volume 1. (1947-French). London: Verso. [ Links ]

Lorde, A (1984) Sister outsider: Essays and speeches. Freedom, CA: The Crossing Press Feminist Series. [ Links ]

Matebeni, Z (2011) Exploring Black lesbian sexualities and identities in Johannesburg. Unpublished Doctoral thesis. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Matebeni, Z (2008) Vela Bambhentsele: Intimacies and complexities in researching within Black lesbian groups in Johannesburg. Feminist Africa, 11, 89-96. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A & Nuttal, S (2004) Writing the world from an African metropolis. Public Culture 16(3), 347-372. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A Dlamini, N & Khunou, G (2004) Soweto now. Public Culture, 16(3), 499-506. [ Links ]

Moffett, H (2014) Feminism and the South African polity: A failed marriage, in Vale, P Hamilton, L & Prinsloo, E (eds) Intellectual traditions in South Africa: Ideas, individuals and institutions. Pietermaritzburg: UKZN Press. [ Links ]

Munt, S (1995) The lesbian flâneur, in Bell, D & Valentine, G (eds) Mapping desire: Geographies of sexualities. London: Routledge (pp 114-1250. [ Links ]

Pile, S (2009) Emotions and affect in recent human geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, 35(1), 5-20. [ Links ]

Ramkissoon, N (2012) Joburg Pride was nothing to be proud of. Times LIVE, http://www.timeslive.co.za/opinion/2012/10/08/Joburg-Pride-was-nothing-to-be-proud-of [ Links ]

Reissman, C K (2008) Narrative methods for the human sciences. London & Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa. Civil Union Act, 2006 (Act No. 17 of 2006). Cape Town: Government Gazette. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa. Sexual Offences Act, 1957 (Act No. 23 of 1957). Cape Town: Government Gazette. [ Links ]

Rink, B M (2013) Que(e)rying Cape Town: Touring Africa's "gay capital" with the Pink Map, in Sarmento, J & Brito-Henriques, E (eds) (2013) Tourism in the global south. Heritages, identities and development. Universidade de Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Geográficos. [ Links ]

Rothenberg, T (1995) And she told two friends: Lesbians creating urban social space, in Bell, D & Valentine, G (eds.) Mapping desire: Geographies of sexualities. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Stevens, G, Duncan, N & Hook, D (eds) (2013) Race, memory and the apartheid archive: Towards a transformative psychosocial praxis. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Thompson, J B (1990) Ideology and modern culture: Critical social theory in the era of mass communication. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Tucker, A (2009) Framing exclusion in Cape Town's gay village: The discursive and material perpetration of inequitable queer subjects. Area, 41(2), 186-197. [ Links ]

Vincent, L (2015) Tell us a new story, in Tabensky, P & Mathews, S (eds) (2015) Being at home. Race, institutional culture and transformation at South African higher education institutions. Pietermaritzburg: UKZN Press. [ Links ]

Visser, G (2003) Gay men, tourism and urban space: Reflections on Africa's "gay capital". Tourism Geographies, 5(2), 168-189. [ Links ]

Wetherell, M (2012) Affect and emotion. A new social science understanding. London: Sage. [ Links ]