Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Psychology in Society

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8708

versión impresa ISSN 1015-6046

PINS no.55 Stellenbosch 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8708/2017/n55a3

ARTICLES

Creative twists in the tale: Narrative and visual methodologies in action

Jill Bradbury

Department of Psychology University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg

ABSTRACT

Narrative methodologies emphasise the temporal quality of both lived lives and told stories, and enable us to attend to the ways in which the grand narratives of history and socio-political life articulate with individual, personal lives or psychological realities. However, the narrative approach entails three key epistemological and/or political problems: 1) the imposition of a particular conception of a "good" narrative (and by implication, psyche or life) that entails logical flow, integration and coherence; 2) the production and re-inscription of a gap between life and story, particularly stories told in research interviews; and 3) individualising single narrators extracted from their contexts. I argue that combining narrative research methods with visual methodologies within an action research paradigm may assist us to work through and against these limitations. Visual methodologies are relatively commonplace as a means to collect data, particularly helpful when stories are difficult to articulate. I suggest extending the use of visual techniques to facilitate creative representation and productive analysis. Examples of innovative visual representations of data illustrate possibilities for challenging the limits above: 1) Repetitive stress injuries: Non-stories and visual techniques for sense-making; 2) Visual tracking of multiple temporal trajectories; and 3) Re-invoking the relational quality of narrated identity.

Keywords: narrative, visual methodologies, (in) coherence, theory-method, relationality, temporality

Introduction

Narrative methodologies emphasise the temporal quality of both lived lives and told stories, and the meaning-making processes of both researchers and participants in the exploration of psychosocial life. The approach enables us to attend to the ways in which the grand narratives of history and socio-political life articulate with/in and through individual, personal lives or psychological realities. In many cases, though certainly not all, participants in narrative research find the process of talking about them-selves a positive or even possibly cathartic experience, enabling new vantage points on their own lives for themselves while simultaneously providing insights for the researcher. In some cases, this process of reflection on a life and the life-world, may have conscientising effects, enabling people to "read the world" (Freire, 1972) in new ways and agentically envisage action for change. However, narrative methodologies are limited and the liberatory possibilities of the framework are often challenged in the process of implementation. There are three key epistemological and / or political problems that emerge: 1) the imposition of a particular conception of a "good" narrative (and by implication, psyche or life) that entails integration, coherence and a logical flow of language; 2) the production and re-inscription of a gap between life and story, particularly stories told in research interviews, and 3) individualising single narrators extracted from their contexts.

I argue that combining narrative research methods with visual methodologies within an action paradigm may assist us to work with, through and against the limitations of narrative, strengthening the theory-method. It is no longer that unusual to utilise visual methods for data collection, for example: photo voice (Kessi, 2011, 2013; Bradbury & Kiguwa, 2012); body mapping (Busch, 2012; Botsis, 2016) or visual autobiography (Esin & Squire, 2013); (spatial and identity) mapping (Futsch & Fine, 2014). These techniques are particularly helpful when stories are difficult to articulate, perhaps due to trauma or other embodied experiences that are typically "beyond words", rendering us speechless (Emmerson & Frosh, 2013), or when the storyteller(s) and audience must cross linguistic or other (classed, raced, gendered) boundaries. Although research participants are always involved in a first layer of analysing their own lives, this active interpretation is typically concealed in spoken language, often deceptively appearing to provide a direct, transparent link to both the interior psychological and exterior social worlds. In narrative research specifically, participants select what to tell, weaving the textured threads of recollected life into the material of a story, fabricating (in the sense of making rather than lying!) a version of reality in the telling. The co-construction of visual data (creating representations of the world) helps to externalise the meaning-making process and make the reflexive and interpretive nature of all data, more apparent.

However, the use of visual techniques in the process of analysing data is less widespread than in the data collection processes described above, and here the primacy of language is typically reasserted and finally fixed in textual form. The textual product conceals the often lengthy and repetitive processes of reading and re-reading the data, selecting what to highlight and what to discard, and organising the data into a coherent form that works to create an analytic account. I suggest that utilising visual techniques, especially in the process of talking through the data in conversations between students and supervisors or between co-researchers, facilitates creative and productive analysis, particularly enabling attention to the structure and context of narrative accounts. First, the process of forming visual compositions of meaning attunes us to relations between ostensibly jumbled, chaotic, incoherent talk of events and feelings that are not amenable to the conventional order and directionality of narrative structure. Instead of imposing the criteria of a "good" story and, by implication, for a "legible life" (Phoenix, 1991), this process provokes us to engage with the narrative organisation provided by participants themselves, often a looser structure that incorporates ambiguities and contradictions. Second, mapping the lines of talk or temporal trajectories of these narratives enables us to form connections between disparate events and experiences in the individual life history, linking these to the wider macro histories of the social world. Visualising the temporal movement of talk and life and the oscillating relations between these domains, creates linkages across the "gap" between life and talk, recognising the interpretive task in both generating and analysing verbal tracts of data. Finally, visual representations of told stories also provide a wide-angle lens to include connections between the person and others within the frame of focus, attending to the relational quality of identity construction.

The article will illustrate the flexible possibilities of such techniques by utilising examples developed in conversation with students1 in a range of projects focusing on identities in-the-making on the margins of South African life: 1) Repetitive stress injuries: Non-stories and visual techniques for sense-making (Haynes-Rolando, 2016; Moleba, 2016); 2) Visual tracking of multiple temporal trajectories (Selohilwe, 2009; Liccardo, 2016); and 3) Re-invoking the relational quality of narrated identity (Haley, 2010; Coats, 2013). These visual techniques are varied and are not intended to establish new conventions but rather represent active processes of analysis developed in dialogue, as triggers for future creative engagement to be developed in and through the content of particular projects.

Narrative theory-method

Narrative is an umbrella term that includes a collection of approaches and methods that vary considerably due to different conceptualisations of the relation between the words of stories and the stuff of life. Some approaches emphasise strict adherence to particular steps in the processes of data collection and analysis that seek to curtail the influence of researchers on participants' stories (for example, Wengraf, 2010, 2011). Others suggest that it is imperative to acknowledge and include the role of the researcher as a coconstructor of the narrator (for example, Riessman, 2008; Josselson, 2013). Methods of analysis similarly range from primary attention to the structure of narratives as temporal flows of events (for example, Labovian coding of text-sorts, Patterson, 2008; Wengraf's (2010) mapping of told stories onto lived lives), to a less exclusive focus on structure and events, linking narrative analyses to other methods such as conversation analysis (Bamberg, 2008) or thematic analysis (the experience and cultural orientated approach of Squire, 2008) or to discourse analysis (for example, Livholts & Tamboukou, 2015). Many different theoretical resources or grand narratives may be brought to bear in the interpretive exercise: for example, Psychoanalysis (Wengraf et al, 2012); Foucault (Tamboukou, 2008); and Marxist theory (Mischler, 2004). Despite this wide range of associated theoretical frameworks and allied methods, narrative is best thought of as a "theory-method" in that the methods and techniques of researching the phenomenon are entwined with a particular conception of the phenomenon. While this is in some sense true of all research and knowledge-making, it is peculiarly pertinent in some frameworks for thinking about human life; inter alia, psychoanalysis, and the clinical-developmental methodologies of both Piaget and Vygotsky. The theory-method of narrative focuses on the pivotal role of language not only in generating stories but in the very constitution of human life, conceptualising persons as temporal and relational phenomena.

Embodied life is lived forwards in time, inexorably moving from birth to death (shaped along the way by various developmental processes, if not stages) in between. Narratives too have a temporal structure, in which concatenations of events create an account of movement from a beginning to what seems to be an inevitable endpoint. But a critical distinction between (biological) lives and stories lies in the vantage point from which meaning is made. Despite the ostensible forward motion of a story that carries us towards its conclusion, the significance of events can only be recognised once their consequences unfold in time (Fay, 1996) or as Kierkegaard claims, "Life is lived forwards but can only be understood backwards" (cited in Crites, 1986: 165). This may seem to imply that the lines of biological development and narrative meaning-making run in opposite directions, however, the two lines are not parallel but intertwined. The articulation of our lives in stories is not only externally orientated and communicative but structures our thinking and actions through an "internal conversation" (Archer, 2000). The de-contextualising possibilities of representational language release us from the exigencies of the present (Hoffman, 2009), enabling us to reflect on past experiences and plan our actions in advance (Vygotsky, 1962; Miller, 2011).

We thus become creatures for whom the past and future are always actively present. Our psychological life is temporal not only because it is developmental (changing and growing more complex across the lifespan) but more importantly, because the horizons of worlds are perpetually shifting across time through the fluid processes of memory and imagination. Psychological life thus entails "time-travelling" (Andrews, 2014) and our actions in the present are always infused with, and oscillate between, the meanings of the past and expectations of the future. Thus, the temporal course of human life is altered by the meaning we make in language. We live in time but are not entirely captured by it, and, in language, the embodied and meaningful worlds become entangled and mutually constitutive. Theoretically framing human life in terms of temporality and meaning-making therefore critically undercuts the typical binary formulation of biology and the social (or the almost-but-never-completely dead, nature-nurture debate). The stories that make our lives meaningful to ourselves and others, both follow and reverse the temporal flows of embodied life, making the past and future, present. Further, we always enact our narratives and narrate our actions in shared cultural languages and, hence, an individual lived-life is joined with (in the sense of articulated with, in joints and knots) social life. This engagement with social others is not temporally bound to the here-and-now but also entails the ever-present effects of the sedimented meanings of historical others in the "narrative unconscious" (Freeman, 2010).

So how does this theoretical conceptualisation of ontology as temporal, relational and meaningful, translate into appropriate methodologies? Narrative interviews create an opportunity for participants to narrate them-selves for the researcher and academic readership in ways that are not prescriptively predetermined, acknowledging the lines of life that lie outside of the moment of the interview in the person's past and future. Techniques of analysis that emphasise the structure of stories similarly take seriously the way in which events and experiences are structured by and for the participant in order to live a meaningful life, one that makes sense for her. Together with this vertical in-depth analysis of individual stories, horizontal thematic analysis across stories can also provide a window into wider socio-historical processes with productive possibilities for political and theoretical purposes.

However, narrative is not a transparent route into the minds of story-tellers or to the social world in which they live. Analysis always entails the tricky process of negotiating between orientations of trust and openness to fully hear participants' accounts, and critical distance that enables the researcher to go beyond what is said or even known by participants themselves (Josselson, 2004). These limitations and complications have led me, in conversation with students about their empirical projects, to explore alternative creative mechanisms of representation in conjunction with the more standard forms of analysis in an attempt to read, capture and convey aspects of storied lives that may otherwise be rendered invisible. Visual modalities may provide new lexicons or alternative vocabularies (Botsis, 2016) that help to articulate aspects of experience, embodiment and affect that are often difficult to put into words. This approach has been particularly helpful when stories disintegrate or are difficult to attend to or make sense of in the telling, and to foreground the temporal and relational qualities of both human life and narratives. To illustrate, I will present first some examples of the kinds of narratives that present analytic challenges, followed by some examples of supplementary visual methods of analysis that develop a different sensibility of interpretation and provide new possibilities of analytic literacy, alternative ways of reading and (re)articulating the narratives of research participants.

Repetitive stress injuries: Non-stories and invisible spaces

Narrating our lives, or turning experiences into stories, entails processes of selection and organisation: not everything that happens can be told. These processes of forming a story are particularly active and perhaps more conscious than in "real" life when the audience for the story is a researcher who is clearly interested in a story worth listening to, implying a life of interest and value. Accounting for ourselves to others (even strangers) is becoming increasingly commonplace in the contemporary "scapes" (Appadurai, 2006) of social media in which we increasingly, even compulsively, seem willing to divulge all in what the psychoanalyst Josh Cohen (2013: x) calls an "unholy alliance of voyeurism and exhibitionism". However, the practices of this divulgence of the self, while ostensibly democratic, open and accepting of multiple forms of the "ordinary" life, are nonetheless highly structured and may, in affording a kind of "celebrity status" to the banalities of middle-class life, serve to further homogenise what makes for a life worth living and telling.

McAdams (2001) suggests that the psychological value of narrative lies in its capacity to generate coherence both diachronically and synchronically. Through narrating ourselves, we create an integrated persona (or personal identity) that endures across time and across multiple social roles. In this view, an identity is formulated in story-form; who we are is the story we tell of ourselves. We have commitments to and expectations of continuities between who we (and others) were in the past and who we (and others) will be in the future, and similarly, across various social contexts. However, the rapid pace of social change and increasingly fractured multiplicities of life, make the task of developing coherent versions of our-selves perpetually open and exceedingly difficult; some would argue impossible or even undesirable (Bauman, 2000). Perhaps in the postmodern world, stories and selves are less coherent but some forms of fracturing and disruption are surely less liberating than others.

Dramatic ruptures to life caused by violent conflict or a disabling accident or illness, fracture coherence, demanding that any attempt to integrate the self, entails a recognition of this rupture and the employment of narrative mechanisms to actively repair or bridge the psychological schism effected. The study of trauma and illness narratives explicates the before-and-after structure of these accounts, hinged by the disruptive event, expressing how the person feels herself to be dramatically changed by the event, but nonetheless, still the same person to whom the event happened, in some ways continuous with the earlier self. Such stories may often take the form of "conversion narratives" (Squire, 2013) whereby the person recreates a new coherence from a shattered life, in colloquial terms, "picking up the pieces" or "putting one's life back together".

In her research with NEETs (Not in Employment, Education or Training) in a "Coloured"2township outside Pretoria, Haynes-Rolando (2016) encountered young men who were eager to talk and to tell extremely detailed stories about their lives. Their narrative accounts of how they landed up here where they are today, unemployed and often trapped in repetitive cycles of drug abuse and spells in prison, are often structured in relation to an early traumatic event that they identify retrospectively as "causing" their lives to take the particular paths that led to their current circumstances. For example, Dylan3 speaks of being "bumped by a car" when he was quite young and attending a good school on a bursary scheme. He describes the accident primarily in terms of the absence of adult care (his father was working in another city and his alcoholic mother unable to provide emotionally or financially for him) that meant he had to daily cross busy streets alone. Because the post-apartheid health care system is highly unequal and remains racialised, no ambulance was called to assist at the scene and he went home with a broken leg. He repeatedly refers to "the bump", at multiple points in his narrative as the point at which his life took a turn for the worse. A similar repetitive compulsion characterises the trauma story of another participant, Alan, who tells of the first time that he stole a mobile phone and how this set him off on a life of petty crime and being perpetually in and out of jail. The event of this PIN (particular incident narrative, Wengraf, 2010) is repeated but in a jumbled, convoluted way with details changing in each retelling as if the specifics are too painful to recall: perhaps he was threatened with rape, perhaps threatened with physical violence; perhaps by the man from whom he first stole or perhaps by someone who threatened him in one or both of these ways to coerce him into stealing the phone; or perhaps indeed he was assaulted and/or raped. The trauma is not yet located in an organised narrative for a coherent self.

While the traumatic narratives of people like Dylan and Alan are formed through embodied personal experience, some traumatic events have collective import, disrupting the narratives not only of those directly involved in the events but shaping the social imaginary and forming the "narrative unconscious" (Freeman, 2010) of wider society. In 2012 the Marikana massacre in which 34 unarmed striking miners were killed (and 78 injured) by police under the instruction and control of the democratic post-apartheid state, shattered the South African national psyche. This event ruptured the existing conversion narrative of the nation: the post-ness of Apartheid exposed as a lie in these brutal acts to maintain the racialised inequalities of the status quo. Moleba (2016) interviewed nine young people in the village of Wonderkop, home to these miners, with a view to capturing the stories of those most directly and personally affected, whose community and families had been explosively and irreparably changed by this immensely significant event. We anticipated stories of life before and after the trauma of the massacre but, puzzlingly, most of the participants barely mentioned the massacre at all, or only when pushed to do so by the interviewer. Initially, we thought this silence might have been produced by the audience of the researcher who, although an "insider" in terms of race, language and age, was an outsider in terms of the critical categories of class and educational status. While not discounting these effects in the heightened political environment of Marikana, attending to the structure of the stories that participants did tell, led us along a different interpretive line. The stories were told in fits of stop-start failed attempts, in staccato-like stuttering and rewinding repetitions. Extracts from three participants illustrate this difficulty in even getting the narrative started:

"Ok. I'm Jennet, I am 27 years old [pause] So, my parents are people who, who, who ... [long pause]. Can we start from the beginning? I'm remembering new things and they are mixing up (confusing) my thoughts. (Interviewer: Ok.) I'm Jennet, I am 26 years old and I live in Rustenburg. I have ... Ok, at home, in my family we are 4 ... uh ... my thoughts are disappearing (running away, scattered)4. Ok, let me start from the beginning again."

"My name is Phinda. I was born and bred here. Is that how you say it? (Interviewer: Yes.) Ok. Thanks. Ja, so I have lived here my whole life. Life here is hard but we manage. Wait, sorry, can I start again?"

"I'm Mzi, and I'm from Mozambique. [Pause] Can I start, over? (Interviewer: Yes.) Ok. My name is Mzi, I'm 28years old and I come from Mozambique. I ... [Pause] Sorry. (Interviewer: It's not a problem, take your time. You can continue any time you are ready.) [Pause] I'm Mzi, and I'm from Mozambique. I work for a Chinese business, I started working here in 2013. I work well here, I don't, have problems. I work because . [Pause]"

While the trauma of the massacre looms large in the national narrative and is certainly not inconsequential to those who live in Marikana, the everyday assault and insults of poverty, unemployment, and HIV are of more immediate personal significance, splintering their lives and eroding identities. The effects are embodied, experienced somatically like repetitive stress injuries that may individually seem not too severe, but cumulatively hurt very badly, beyond bearing.

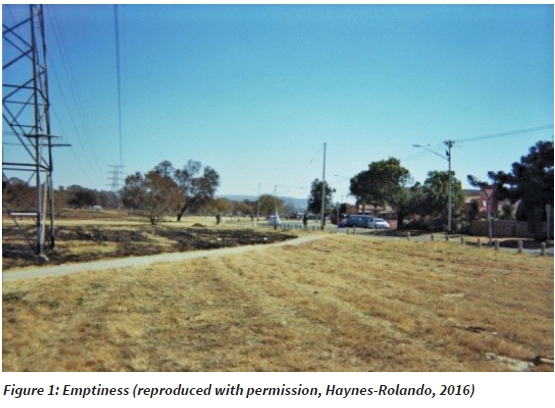

The stop-start, traumatic non-stories of Moleba's participants told in the barren landscape of poverty resonate in the desolate photograph below taken by one of Haynes-Rolando's (2016) participants.

Deon: "It didn't, come out nice. As you can see there, laying under the tree. I dunno why these people there but every day there is people laying there. (Interviewer: Ok. Laying under the tree.) I dunno why but every day. I took it because I need a job actually because I don't do nothing at home. I am just tired of sitting at home cleaning, doing the same stuff everyday. And, that people reminds me of my own life. (Interviewer: Mmm.) Because they are doing nothing every day. [...] this is an empty space here, empty plot, not a plot, you can see it's, there needs to be something done."

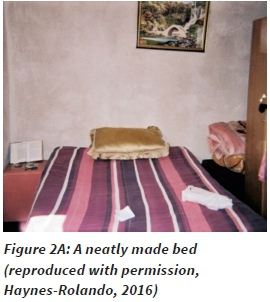

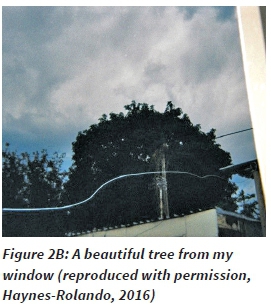

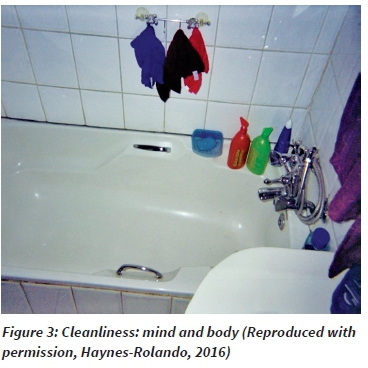

The cycles of drugs and "trouble with the law" and the emptiness of unemployed life make it difficult for these young men to think about futures or about life with any sense of directionality. However, Adichie (2009) warns us of the "danger of the single story" entailed in flattening people's lives and reducing them to definition in terms of either big trauma events such as the Marikana massacre or the stereotyped accounts of NEETs or "coloured identity". Haynes-Rolando's (2016) use of photovoice data enables us to gain a much more complex sense of who these young men are. Yes, they are young unemployed men, with little education, many having dropped out of high school, and often in trouble with the law. But the photographs below (Figures 2A, 2B, 3 and 4) that they took to represent themselves, convey the stories of young men who appreciate the beauty of nature, are engaged in domestic chores and value the simple pleasures of home such as a clean bath and a carefully made bed, and are deeply concerned about the wellbeing of others, gently caring towards younger boys on the street.

Alan: "And here, I look to check this view sometimes ne, when I'm lonely, I just stand there by the sliding door, at the back, there is two sliding doors at the front and one at the back and I stand there, every day watching this view, if I stand up in the morning make my bed, nice."

Deon: "Yes, and as you can see here is a bath, with shampoo there, lots of stuff, I need to be clean, and there is people who doesn't, have homes, they homeless can't, wash, that's a big, how can I say, uhh ... I'll come to it now, but it's a lot of blessings for me because I don't do nothing actually."

Michael: "Ja, very, but I'm praying, ja, and these boys here ... [laughs] I love them so much, ay, their mother left, them since they were 5 months, so I just got them, come, sitting, give them some food, ja."

While participants also spoke of and took photographs portraying hyper-masculine roles in gang membership, crime activities, circles of drug-taking and of women as little more than decorative objects in their world, these were balanced by many more of the kind reproduced here, reflecting vulnerability, domesticity and communities of care. These visual data enabled the participants to speak about aspects of their lives and identities that are difficult to narrate verbally and might otherwise have remained invisible, providing us with a view on their worlds that disrupts the "single story" (Adichie, 2009) of these young men.

Visual representation thus enriches the narrative approach, offering us both epistemic and political resources for thinking through stories that might otherwise be discarded as uninteresting or unimportant (Moleba's non-stories or Haynes-Rolando's empty images), and resisting reductive dehumanising accounts of complex lives (as suggested by the label "NEETS"). This approach enables us to recognise the rich variety and complexity of human life and validate the persistent practices of meaning-making in which all people engage, even in conditions of desperate poverty and social alienation.

Visual tracking of multiple temporal trajectories

Narrative analysis, as distinct from other qualitative methodologies, focuses on the temporal movement of stories told as a way to understand the lived life. Gergen and Gergen (1986) adapted the structures of Aristotelian comedies and tragedies to describe psychological theories in narrative terms, as "progressive" (for example, developmental theories such as Piagetian cognitive development), "regressive" (for example, psychoanalysis that unravels a life backwards), or "stable" (for example, taxonomic or classificatory descriptions). By extension, we could think about these as templates for lives that move in either a generally positive upward trajectory towards goals or peak events, or slide or spiral downwards in regressive or negative ways, or are characterised by stability or stasis with little movement.

Selohilwe (2009) conducted two sets of narrative interviews with young black women at the point of leaving high school and again, a year or so later. This is obviously a significant time in all young people's lives, usually a peak moment in a progressive forward-looking developmental line. However, Selohilwe found that neatly patterned Aristotelian templates were quite inadequate to describe and represent the lives of these young South Africans. In many cases, their lives were already extremely complex, characterised by many ups and downs, lurching from crisis to crisis, and including multiple traumatic events that we would ordinarily associate with much older people. Selohilwe (2009) traced the movement and peaks and dips of her participants' narratives and represented these graphically. Khanyise's story represented in Figure 5A below, is an illustrative example, "characterised by a combination of progressive and regressive lines" (Selohilwe, 2009: 61) including traumatic events such as the death of her mother when she was 9 years old, repeated suicide attempts, and multiple movements between foster homes. The hopeful moments of her story include hope for a "normal" life triggered by these spatial movements, although soon dashed. The interview happens just as she finishes school and feels her life is once again on an upward trajectory. However, many other participants in this study told stories that closely resembled the non-stories of Moleba's (2016) and Haynes-Rolando's (2016) studies. Rather than the "stable" narrative lines suggested by Gergen and Gergen (1986) these narratives (such as that of Mandisa below in Figure 5B) suggest stasis and stagnation, represented graphically in the flat-lining of life support machinery, when bodies become the living-dead.

Although we are reminded by the photographs of Haynes-Rolando's participants above, that all lives are complex and include love, beauty and joy, many of Selohilwe's (2009) participants experienced the critical phase of leaving school as empty of promise, in which the "opening up" of future space that is typically liberating for young people was experienced as barren and formless. These lives that feel empty of possibilities instantiate in personal terms the extreme inequalities of South African education and the failed promises of schooling that leads neither to higher education nor employment for so many black youth (Alexander, 2013). Global patterns of the intergenerational reproduction of socio-economic inequality through schooling (Picketty, 2015) are reflected in exaggerated and racialised ways in South Africa. For young people caught in this limbo, the identity crisis (Erikson, 1970) of adolescence is both interrupted and extended, perpetually unresolved or, perhaps, not even a question.

Liccardo's study in 2015 also focused on the lives of young black women but unlike the participants in Selohilwe's study, in this case, the participants had not only managed to access higher education but were students in, or graduates of, the elite fields of SET (science, engineering and technology). These young women told stories of belonging and alienation (Yuval-Davis, 2011) at university. Unlike Moleba's (2016) participants who struggled to find a way to articulate themselves in narrative form, these young women told very long, complex stories of their lives, traversing multiple boundaries of class, race and gender to find themselves in the role of "black woman scientist". Their narratives were characterised by excess (one interview was over four hours long!), a surplus of meanings, propelled by an active desire to tell their stories, to articulate their experiences. Liccardo was confronted with the converse problem to Moleba: how to reduce these incredibly rich data in ways that would retain their richness and density and remain respectful of participants' own interpretations of their lives. The figure below was developed by Liccardo (following Wengraf, 2010, 2011), juxtaposing the chronologies of the "lived life" and "told story".

The temporal flow of the interview talk is tracked on the y-axis while the chronology of life experiences is mapped along the x-axis. This creates a visually compelling representation of the zig-zag motion of the narrative, in which Alala initially tells her story chronologically, forward from a moment in school that she recalls when her artistic talent was not recognised. But this early moment proves to be an anchor point for her story, shaping its movement as she shifts back and forth between experiences in the present and earlier moments in which significant others either do or don't recognise her talent. Although the second half of her interview narrative is located predominantly in the recent past or present, the first part of the interview is characterised by major jumps back and forth in time and considerable weight is given to these childhood memories which coalesce and coincide with present experiences in the telling. Although she is a successful young woman science student, she is still concurrently, a young girl desperate for recognition for her art. The visual encoding of talk in this "weave story-maze" enables us to literally see the ways in which the temporal flow of life is reorganised in narrative and, by implication, in the construction of a narrative identity. Liccardo's analysis thus works productively with the gap between lives and stories. Although she takes great care to meticulously document the minutiae of the participant's phenomenological account, she does not treat the interview narrative as a transparent vehicle to access the "truth" of the participant's life. Through mapping the temporal flows of talk and events in relation to each other, new patterns of meaning become evident.

While Selohilwe and Liccardo's visual representations of temporality have different purposes and take quite different forms, both demonstrate the ways in which the ostensibly unlinear unfolding of time in the material world is experienced as highly variable. Selohilwe (re)presents life as crowded with events and fluctuating between affective extremes for some, and flat, static and directionless for others. Liccardo's tracking of the temporal lines of the narrative told in the interview in relation to experiences in the chronological flow of life, serves to highlight the to and fro movement of autobiographical time (Brockmeier, 2000). Narrative analysis is often restricted in focus to the verbal (and then textualised) accounts generated in interviews, separating the stories of life from the inaccessible world of participants' experiences. These visual representations serve to draw these different domains together. In juxtaposing the timelines of talk and life, the analysis must attend to the linkages between narrative and the material world, and to the ways in which narrative identity construction in psychic time, disrupts unlinear developmental accounts.

Re-invoking the relational quality of narrated identity

The storied version of experience produced in an interview is by definition an individual narrative, providing a singular view on the world as recollected and imaginatively reconfigured by a particular person. The participant is both narrator and protagonist in this story of how she came to be the person that she is today, linking events together in particular ways both consciously and unconsciously to account for her-self. Despite the parenthetical effects of the "one-on-one" interview process, the person with whom we talk (and of course the researcher herself too) carries the voices of others into the room. Human beings are never singular even when alone, rather, we are constituted by the internalised others of our social world. However, narrative analysis often serves to undercut this conceptualisation and to sever these connections to others in the focus on an individual story. Connections may later be drawn between and across narrative interviews to provide insights into macro social structures and how individuals are positioned within them, but the interpersonal networks of research participants are often lost.

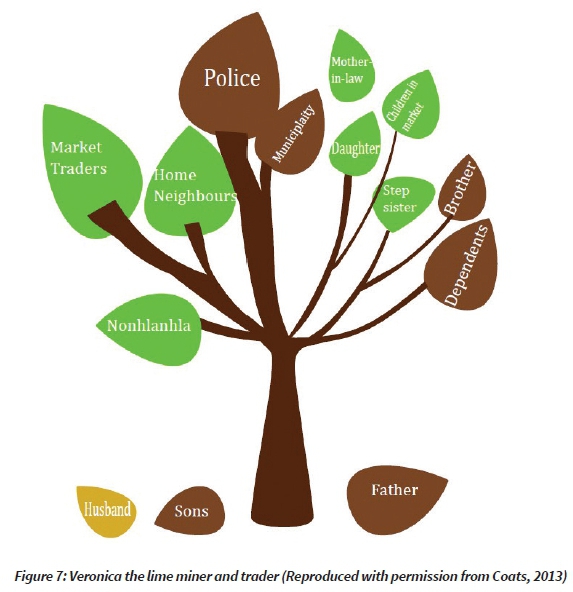

This section presents two examples of visual representation of data that attune our attention to the relational quality of human life. Coats (2013) conducted narrative interviews with women informal traders in the Durban city market. Warwick Junction is a very busy daily market, situated at the confluence of the major taxi ranks and train station of the city. Although it is an extremely old and well-established market, historically this informal sector was relatively un-regulated, aside, that is, from the overarching apartheid zoning of city-space that relegated black business to operating informally on the edges of the city in this space. The market has burgeoned in size and business traffic since the advent of democracy and there are now several mini-markets each specialising in particular goods or services, selling anything and everything from meat, fish and fresh vegetables to traditional herbs and medicines, imported plastic goods, music and traditional beadwork. Coats interviewed women traders in the market who often combined work to produce goods in peri-urban or rural homes, with this marketplace trade, sometimes necessitating sleeping on the streets of the market for weeks at a time with their goods for sale. This spatial mobility means that these women are vulnerable to sexual and other forms of violent abuse. Policing of the area should offer protection from these threats but compounds the precarity of life and is experienced as hostile as their primary focus seems to be on enforcing city regulation of trade (such as who has permits to sell what and preventing people from using the market as residential space). The narratives of these women are woven together with the stories of multiple others in their life-histories and from their two coexistent worlds of "home" and the market. As Futsch and Fine (2014: 54) suggest, psyches are always populated with people from other places and, in psychological terms, "... space can be embodied, metabolized, and carried over time within a person". The image of a tree, both rooted and growing, was chosen by Coats to represent these relationships, illustrated by the case of Veronica in Figure 7.

This participant does not fit the conventional stereotype of women street traders selling a few fruits by the side of the road. She is engaged in hard (typically masculine) labour, mining lime in her home area for weeks at a time and then changing places with other women miners in the market to sell these lime balls in the Warwick junction market. The size of the leaves represents the weighting afforded to the role of others in her story: leaves on the ground, those deceased; the brown leaves, negative and the green, positive, relationships, with the intensity of colour conveying the depth of these emotions. Only once this image had been produced did a pattern in these relationships appear starkly obvious: the men in her life, both formal city officials (particularly the police) and family members were experienced as negative and hurtful, whereas the women offer a positive living network of support. While this may have become evident through more conventional forms of analysis, organising the data in this image literally enabled the researcher to "see" the gendered pattern underlying the words of Veronica's story.

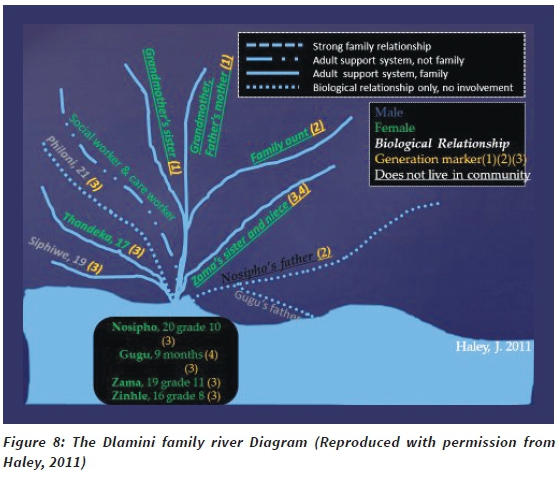

The final example of visual analysis is drawn from the work of Haley (2010) who conducted work with children living in child-headed households. In talking with these children [defined as such by either being under the age of eighteen (the age of majority in South Africa), and/or still in school] she heard the stories of how they came to be children who, as they describe themselves, "live alone" (Haley & Bradbury, 2015). However, like Coats, she also heard stories of webs of relationships with family and community members, both past and present. The complexity of these networks were quite unfamiliar to an ear attuned to a conventional nuclear family structure, with characters entering the narratives of protagonists' tales in seemingly random or confusing ways. Conventional anthropological tree diagrams that represent African extended families and kin systems proved equally inadequate and Haley devised a new more fluid representation of relationships in rivers and tributaries that flow in and out of these child-headed households.

This form of representation enables the researcher to focus on biological and non-biological relationships, intergenerational structures and on the ways in which the ostensibly private enclosed domestic space of the "child-headed household" is permeable and interconnected in webs of relationships, both in the immediate spatial context where they live, and beyond. This visual analysis enabled attention to new emergent family forms that challenge the definitional boundaries between adults and children, the gendered hierarchies of domestic life, and the sometimes overly simplified and romanticised notions of family and community (Haley & Bradbury, 2015). The difficulties of these children's lives are revealed to be less about the emotional and social texture of the home and more about macro structural difficulties associated with their minority status in engaging with officialdom. By defining these households as stand-alone entities and the heads of these households (typically adolescent girls) as children, they are legally marginalised with respect to property rights and access to health, educational and other resources. Even participating in the research project proved troublesome without legal guardianship to grant "permission" for these young people despite the fact that they operate in highly responsible, independent adult ways on a daily basis.

Haley's river diagrams of young families, like the gendered trees of the women informal traders in Coats's study, serve to visualise individual lives in connection with the lives of others, drawing into our field of attention, places and people beyond the individual participant, beyond the parameters of the interview room. Narrative research typically focuses on the story of the "whole" life of an individual person (for example, Wengraf, 2010; Freeman, 2013) even if this life is then read together with the narratives of other similar participants and articulated with theory to an analysis of wider social structures. Some narrative researchers (for example, Bamberg, 2008; Riessman, 2008) extend the frame beyond the individual being interviewed to include the audience of the interviewer and the role that the interview context plays in co-constructing the narrative. Nonetheless, this widening of focus remains highly restricted and anchored to the individual life. By contrast the visual representation of these trees and rivers (both organic metaphors, alluding to living processes) foreground the voices and meanings of others within the life-story, highlighting the relational construction of narrative identity. In both cases, the process of creating these images worked to bring these relationships into focus, representing the sense-making practices of participants in generating their narratives, and enabling a further layer of interpretation by the researchers.

Conclusion

The range of visual techniques presented varies considerably, from quite conventional diagrammatic graphics to more creative, looser representational images. While they may be more or less successful or appealing as visual products, they illustrate the process of visualising data. In each case, the inventive visual representation offers a different way to sense the embodied, affective worlds of participants. While I would not like to overstate the possible transformatory effects of these analytic techniques for the discipline of psychology, narrative research or, more importantly, for the lives of participants, these shifts may have both epistemic and political value. Individual agency may shift in the documenting of a life or narrating one's self in the research process but this may not be enough. In most cases, the possibilities for collective action that might have emerged from these analyses were unfortunately truncated due to the constraints of producing research for degree purposes. However, we should also not imagine that research must always have immediate utilitarian value or that there is always a direct relation between research and action or change in life-worlds. Neither should these suggested visual methods mislead us into thinking that the visual more closely resembles "reality" than words as all forms of representation both entail and require interpretation. But the creative innovations of each project presented here provoke us to think differently about our meaning-making roles as researchers both in the interface with participants and in the subsequent analytic role.

Visual data collection methods involve participants in documenting and reflecting on their worlds, enabling them to narrate lives that may be difficult to both tell and hear (such as the stories of youth trapped in the repetitive stresses and strains of poverty in the studies of Selohilwe, 2009, Moleba, 2016 or Haynes-Rolando, 2016). It is hoped that collating examples of innovations in visual methods of analysis may encourage future researchers to embrace rather than eschew creativity as an integral part of the analytic task. Counterintuitively, spatialising the temporal flow of told (and heard) stories makes the temporality of lived life more evident (as illustrated by the work of Selohilwe, 2009 and Liccardo, 2015). Visualising the narrative also enables us to include the life stories of others that are entangled with that of the person interviewed (as the images of Haley, 2010, and Coats, 2013 demonstrate). If we see and read the world (Freire, 1972) differently, these new forms of knowledge production may help us to incrementally shift the "weight of the world" (Bourdieu, 1999). Twisting narratives into new visual shapes, makes new perspectives possible, enabling us to attend to lives, or aspects of lives, typically rendered silent and invisible, and foregrounds the critically important qualities of temporality and relationality in human life.

Acknowledgements

1. I would like to acknowledge all the students with whom I have worked over the last decade, particularly but not only, those whose work is presented here with their permission and formally referenced. The creative suggestions for analysis that I argue for in this paper are the products of our interactions, grappling with interpreting data. I am thankful for the ways in which their diverse research interests and particularly their engaged relations with their research participants, have provided a cumulative texture and weight to our collective thinking about identities in contexts of change. By drawing together examples from multiple different in-depth projects, this article is one attempt to address "the challenge of accumulating knowledge" (Josselson, 2006: 3) posed by narrative (and to varying degrees, all qualitative) research.

2. Earlier iterations of this paper were presented at a series of workshops, Narrative research: Methods for participation and social transformation, at the University of East London, University of London, and the University of Edinburgh in November 2016. I gratefully acknowledge funding from the NCRM (National Centre for Research Methods) through the International Visitor Exchange Scheme (IVES). Thanks to all participants for rich discussions that pushed my thinking in critical, creative ways. Particular thanks to my co-presenter, Michelle Fine from City University of New York (CUNY) for her provocative and contagious energy, and to our generous collegial hosts from the Centre for Narrative Research at the University of East London, Molly Andrews and Corinne Squire.

3. The paper was refined through the useful comments of the two anonymous reviewers and particularly by the meticulous attention to detail of the editors of PINS - thank you.

References

Adichie, C (2009) The danger of a single story. https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamandaadichiethedangerofasinglestory. Accessed: 13 July 2016. [ Links ]

Alexander, N (2013) Thoughts on the new South Africa. Johannesburg: Jacana. [ Links ]

Andrews, M (2014) Narrative imagination and everyday life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Appadurai, A (2006) Disjuncture and difference, in Durham, M G & Kellner, D M (eds) Media and cultural studies: Key works. 584-603. London: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Bamberg, M (2008) Small text and talk. An Interdisciplinary Journal of Language, Discourse Communication Studies, 28(3), 377-396. [ Links ]

Bauman, Z (2000) From pilgrim to tourist, in Hall, S & du Gay, P (eds), Questions of identity (pp 18-36). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Botsis, H (2016) Subject positioning in the South African symbolic economy: Student narratives of their languages and lives in a changing place. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P (1999) The weight of the world: Social suffering in contemporary Society. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Bradbury, J & Kiguwa, P (2012) Thinking women's worlds. Feminist Africa,17, 28-47. [ Links ]

Brockmeier, J (2000) Autobiographical time. Narrative inquiry, 10(1), 51-73. [ Links ]

Busch, B (2012) The linguistic repertoire revisited. Applied linguistics, 33(12), 503-523. [ Links ]

Coats, T (2013) Reading between the lines: Exploring the telling, hearing, reflective and relational components of women traders' narratives. Unpublished MA thesis. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Cohen, J (2013) The private life: Why we remain in the dark. London: Granta. [ Links ]

Crites, S (1986) Storytime: Recollecting the past and projecting the future, in Sarbin, T. (ed) Narrative Psychology: The storied nature of human conduct. New York: Praeger. [ Links ]

Emmerson, P & Frosh, S (2004) Critical narrative analysis in Psychology. London: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Erikson, E H (1970). "Identity crisis" in perspective, in E.H. Erikson, Life history and the historical moment. New York: Norton. [ Links ]

Esin, C & Squire, C (2013) Visual autobiographies in East London: Narratives of still images, interpersonal exchanges, and intrapersonal dialogues. Forum: Qualitative social research, 14(2), Art.1. [ Links ]

Fay, B (1996) Contemporary philosophy of Social Science: A multicultural approach. London: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Futsch, V & Fine, M (2014) Mapping as a method: History and theoretical commitments. Qualitative research in psychology, 11(1), 42-59. [ Links ]

Freire, P (1972) Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder & Herder. [ Links ]

Freeman, M (2010) Hindsight. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Freeman, M (2013) Axes of identity: Persona, perspective, and the meaning of (Keith Richards's) Life, in Holler, C & Klepper, M (eds) Rethinking narrative identity: Persona and perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [ Links ]

Gergen, K J & Gergen, M M (1986) Narrative form and the construction of psychological science, in Sarbin, T (ed) Narrative psychology: The storied nature of human conduct. New York: Praeger. [ Links ]

Haley, J (2010) Child adults / Adult children: Growing up in KZN. Unpublished MA thesis. University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. [ Links ]

Haley, J & Bradbury, J (2015) Child-headed households under watchful adult eyes: Support or surveillance? Childhood, 22(3), 394-408. [ Links ]

Haynes-Rolando, H (2016) Through our eyes: An action research project exploring the identities and experiences of NEETs in a South African township. Unpublished MA thesis. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Hoffman, E (2009) Time. London: Profile Books. [ Links ]

Josselson, R (2004) The hermeneutics of faith and the hermeneutics of suspicion. Narrative inquiry, 14(1), 1-29. [ Links ]

Josselson, R (2006) Narrative research and the challenge of accumulating knowledge. Narrative inquiry, 16(1), 3-10. [ Links ]

Josselson, R (2013) Interviewing for qualitative inquiry: A relational approach. New York: Guilford. [ Links ]

Kessi, S (2011) Photovoice as a practice of re-presentation and social solidarity: Experiences from a youth empowerment project in Dar es Salaam and Soweto. Papers on social representations, 20(1), 7.1-7.27. [ Links ]

Kessi, S (2013) Re-politicizing race in community development: Using postcolonial psychology and photovoice methods for social change. PINS (Psychology in society), 45, 17-35. [ Links ]

Liccardo, S (2015) Re-imagining scientific communities in post-apartheid South Africa: A dialectical narrative of black women's relational selves and intersectional bodies. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Livholts, M & Tamboukou, M (2015). Discourse and narrative methods. London: Sage. [ Links ]

McAdams, D (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of general psychology, 5(2), 100-122. [ Links ]

Miller, R (2011) Vygotsky in perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Mischler, E G (2004) Storylines: Craftartists' narratives of identity. Boston: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Moleba, E (2016) (Re)Writing the self: An action research project exploring the narrative identities of young people in Marikana, South Africa. Unpublished MA thesis. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Patterson, W (2008) Narratives of events: Labovian narrative analysis and its limitations, in Andrews, M, Squire, C & Tamboukou, M (eds) Doing narrative research. London: Sage. [ Links ],

Phoenix, A (1991) Young mothers. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Piketty T (2015) The economics of inequality. Boston: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Riessman, C K (2008) Narrative methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks, Ca: Sage. [ Links ]

Selohilwe, O (2009) Tracking the future: Young women's worlds. Unpublished MA thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. [ Links ]

Squire, C (2008) Experience-centred and culturally-oriented approaches to narrative, in Andrews, M, Squire, C & Tamboukou, M (eds) Doing narrative research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Squire, C (2013) Living with HIV and ARVs: Three letter lives. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Tamboukou, M (2008) A Foucauldian approach to narrative, in Andrews, M, Squire, C & Tamboukou, M (eds) Doing narrative research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L S (1962) Thought and language. (Translated by E Hanfmann & G Vakar.) Cambridge, Ma: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Wengraf, T (2010) Qualitative research interviewing. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Wengraf, T (2011) Short guide to BNIM interviewing and interpretation. London East Research Institute, University of East London, UK. [ Links ]

Wengraf, T, Chamberlayne, P & Bornat, J (2012) A biographical turn in the social sciences? A British-European view, in Goodwin, J (ed) SAGE biographical research. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Yuval-Davis, N (2011) The politics of belonging: Intersectional contestations. London: Sage. [ Links ]

1 See Acknowledgements.

2 The Apartheid race category "Coloured" is used here as this is the way in which participants in the study self-identified. Foi South African readers this historical label works to position the participants in a particular way in the racialised socio-economic hierarchies of contemporary South Africa. For other readers, the participants can be understood to be Black and / or "mixed race".

3 All participants from all studies were assigned pseudonyms.

4 This interview is translated and these alternatives are provided in brackets as it was difficult to provide an accurate direct translation from SeSotho into English.