Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Psychology in Society

versión On-line ISSN 2309-8708

versión impresa ISSN 1015-6046

PINS no.50 Stellenbosch 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8708/2016/n50a8

BOOK REVIEW

Martin Terre Blanche; Khonzi Mbatha

Department of Psychology, University of South Africa, Pretoria

Mountian, liana (2013) Cultural ecstasies: Drugs, gender and the social imaginary.

London: Routledge.

ISBN 978-0-415-58386-2 pbk. Pages viii + 160

The first thing to know about this book is that it is rather nicely, but somewhat misleadingly, packaged. The back cover starts with an endorsement by Nancy Campbell in which she claims that the book "weaves together an intricate web for the purpose of giving voices to those who are defined and silenced by virtue of their addictions". If you take this to mean, as we did, that the book reports on and valorises ways that drug users themselves (as opposed to experts and such) speak about doing drugs, then know that this is not the case. Instead, it unpacks and critiques mainstream writing and talk about drugs - of the sort that circulates in churches, newspapers, schools and the criminal justice system - in the process perhaps, to some extent, forging a new language that drug users (and others) could tap into.

It is also rather easy to be misled by the front cover, which features CULTURAL ECSTASIES in large letters, together with a retro-looking drawing of a rather prim (but sensuous) young woman about to pop an oversized pill of some sort. If you imagine, as we did, a jazzy, hallucinatory (but sharply ironic, of course!) meditation on the double ecstasy (biological and cultural) of being swept off one's feet by drugs, then again you are in for a disappointment. This is a conventional, broadly discourse analytic, academic text.

Finally, the subtitle ("drugs, gender and the social imaginary") could be understood to suggest that the book is in essence a gendered take on drug-taking, which it is not. Gender comes into it, particularly in chapter 6 (which is entirely focussed on gender), but as a whole the book does not operate from a particularly gendered perspective.

However, if one accepts that in this case the book and its cover are two different things (which is supposedly true of all books of course) we found that it had a great deal to offer about how the current taken-for-granted world of drugs and drug-taking has been socially constructed over time.

Ilana Mountian has worked as a clinical psychologist in Brazil and the United Kingdom, but is also a researcher and an academic, and appears to write primarily for an audience of (critical) academic psychologists and other social scientists. However, the intention is clearly also that some "mainstream" psychologists, social workers, legal professionals etc. who work in the field of "drug abuse" will dip into the text. Perhaps partly to cater for such readers, Chapter 2 reviews some basic theoretical concepts from social constructivist, psychoanalytic, feminist and postcolonial approaches. First laying the theoretical groundwork in this manner sounds like a good idea, but we struggled to become enthusiastic about this chapter. In parts the exposition seemed too basic (do we really need to be told this stuff again?) and in parts too complex and cryptically presented. Here is an example: "For Lacan, the imaginary is related to illusion, to identification, narcissism, image, imagination; related to wholeness, duality and similarity. Yet the imaginary dimension is structured by the symbolic." (p 12)

This is no doubt correct, but tells those who know something about Lacanian theory nothing new, while at the same time probably meaning almost nothing to novices. So we think theoretically more informed readers will be bored by Chapter 2 while less informed ones might get bogged down in it and never get to the more interesting stuff. Our advice is to skip the theory chapter (you can always catch up on that sort of thing later, if and when it becomes necessary) and instead to head straight for Chapter 3 which provides an interesting historical overview of discourses that have created the world of drugs and drug use differently in different epochs.

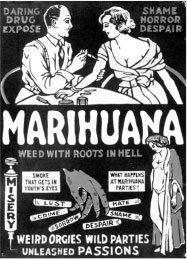

Mountian paints a fascinating picture of the medical, juridical and other realms that have fostered and been fostered by discourses that create drugs as, for example, dangerous narcotics versus harmless recreational aids, legitimate versus illegal substances, and as associated with dangerous social elements such as communists and homosexuals. Along the way we get fascinating glimpses (and interpretations) of, for example, prohibition, the temperance movement, romanticisation of opium use, moral panics around newly fashionable drugs such as cocaine, and so on. There is also a hefty dose of theory around, for example, race, class, gender and sexuality, but here presented in the context of rich historical materials, rather than abstractly as in Chapter 2. For some, this quick tour through the history of drug use as a social phenomenon (rather than say a series of individual psychological traumas) might not be that new, but the analysis is sharp and fast-paced, and there are many entertaining moments (such as the 1934 movie poster and accompanying analysis on page 50). For others, such as perhaps some clinical psychologists, this kind of take on what drug use is about might come as an eye-opener.

Chapters 4, 5 and 6 expand on Chapter 3 by considering in more detail the question of how addiction functions not (only) as an individual challenge, but as a socially constructed reality that shapes how it is possible for us to act in relation to drugs (Chapter 4), various metaphors ("war on drugs", addicts as victims or as morally fallen, or as mentally ill, or as glamorous outsiders) that demarcate the universe of drug use we have come to live in (Chapter 5), and drug-taking as a heavily gendered practice (Chapter 6).

The final, short, chapter is somewhat different in that it tackles the issue of drug policies - that is, the carefully reflected upon, supposedly rational and systematic ways in which society chooses to respond to the drug "problem" (as opposed to the unruly, uncontrolled discourses about drugs reviewed in the rest of the book). Mountian nicely demonstrates how these policies, despite their pretentions to being thoughtful and considered guidelines, tend to simply reproduce the fashions and prejudices and blind spots of whatever social discourses are dominant at any particular time. Her analysis of how an understanding of drug-taking as gendered is both absent and present in drug policies is especially interesting (and to some extent contradicts our earlier claim that the book is not really primarily about gender). Unfortunately, though, the final chapter comes across as severely truncated - the exposition around policies feels incomplete and the job of concluding the book as a whole (pulling together all the various threads) is rushed through in just two paragraphs.

Overall, we think Mountian has made an important contribution to the literature on drugs and produced a text which, although rather different from what the cover might lead one to imagine, is in fact an interesting, fun and in places inspiring read.