Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Psychology in Society

On-line version ISSN 2309-8708

Print version ISSN 1015-6046

PINS n.45 Stellenbosch Jan. 2013

ARTICLES

The changing face of "relevance" in South African psychology

Wahbie Long* ; Don Foster

Department of Psychology, University of Cape Town. Rondebosch 7701. wahbie.long@uct.ac.za

ABSTRACT

For several decades, psychology in South Africa has been accused of lacking "relevance" insofar as the country's social challenges are concerned. In this paper, the historical and discursive contours of this phenomenon known as the "relevance debate" are explored. Since the notion of "relevance" entails an assessment of the relationship between psychology and society, the paper presents the results of discursive and social analyses of forty-five presidential, keynote and opening addresses delivered at annual national psychology congresses between 1950 and 2011. These analyses reveal the close connection between discursive practices and social matrices, and, in particular, the post-apartheid emergence of a market discourse that now rivals a longstanding discourse of civic responsibility. This has created a potentially awkward juxtaposition of market relevance and social relevance in a nation still struggling to meet transformation imperatives.

Keywords: discourse, ethnic-national relevance, market relevance, social relevance, South African psychology

The question of "relevance" continues to generate discussion among psychologists in South Africa. Whether in reference to the claimed cultural imperialism of its teaching (Ahmed & Pillay, 2004), the skewed racial demographics of its professionals (Pillay & Siyothula, 2008) or the apparently apolitical interests of its researchers (Macleod & Howell, 2013), the sentiment prevails that, as during the apartheid years, psychology remains indifferent to the lived realities of most South Africans. In turn, this has given rise to widespread concern about the commitment of the country's psychologists to the post-apartheid project of nation-building.

Part of the reason why the debate about "relevance" has never been resolved, is that psychologists down the years have understood it to mean different things (Dawes, 1986; Biesheuvel, 1991). One version - social relevance - involves the expectation that the discipline contribute to human welfare by ensuring the psychological wellbeing of society (Nell, 1990). According to another iteration, cultural relevance demands that psychology be Afrocentric in order to meet the mental health needs of the country's black African majority (Holdstock, 1981). And to cite a third elaboration, market relevance encourages the international benchmarking of disciplinary outputs.

Underlying talk of "relevance", however, is the notion of a "public good" that is "unendingly contestable, dangerous in the extreme, inevitably manipulated by elites" (Mansbridge, 1998: 3). It has long been known, for example, that the philosophical meaning of the "public good" is historically variable and therefore unfinalisable. As for the political meaning of 'public', it, too, is equivocal: the 'public' is neither unitary nor homogeneous, while the multiple communities that comprise it are not givens but are constituted historically and discursively (Calhoun, 1998). By implication, the parameters of "relevance" are historically relative and reflective, therefore, of specific socio-political contingencies. With a conceptual terrain that is constantly in flux, there is an air of inevitability, then, about this most enduring of controversies.

Accordingly, this paper examines the historically variable meaning of "relevance" in South African psychology. It notes specifically how the various inflections of "relevance" have been wedded to particular socio-political matrices. It observes, further, the rise of a newfangled rendering of "relevance" in recent years, in which market considerations appear to contradict what was once an emancipatory agenda. With "social relevance" still an emblematic watchword in the discipline (Cooper & Nicholas, 2012), the paper concludes by reflecting on the significance of the rise of "market relevance".

MATERIALS AND METHOD

In light of its elusive definition, the operationalisation of "relevance" is not a straightforward matter. This study adopts a correspondingly broad understanding of the term - not without its shortcomings - and defines "relevance" as "the expected value [disciplinary activities] will have for society" (Hessels, van Lente & Smits, 2009: 388). Any historical study of "relevance", therefore, must account for the (changing) relationship between psychology and the wider public. Consequently, since the psychological association functions as a barometer for this relationship (see Sokal, 1992), it was decided to examine presidential, keynote and opening addresses delivered at annual national psychology congresses in South Africa. In contrast to ordinary conference papers that recount little more than the research activities of their presenters, one would expect such addresses to speak to issues of public import, implicating in so doing the vexed notion of "relevance".

Speeches were gathered from a number of sources: the National Library of South Africa (both its Cape Town and Pretoria branches), the Raubenheimer archive at Stellenbosch University, the Mayibuye archive at the University of the Western Cape, the Pretoria branch library of the University of South Africa, the PsySSA archive, directly from the speakers in question and, in cases where the latter had passed on, from their surviving colleagues and acquaintances.

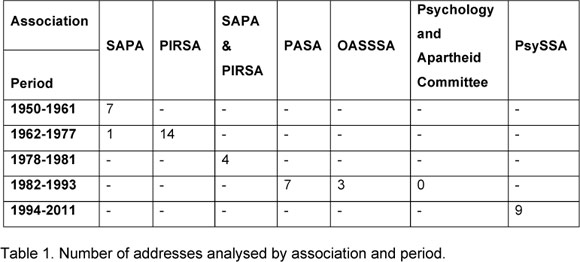

A data corpus consisting of sixty-four speeches was generated. Of these, twenty-six were presidential addresses, eighteen were keynote addresses, seventeen were opening addresses and three were guest addresses. However, not all of the collected addresses were selected for analysis. A handful of speeches amounted to no more than summaries of the speaker's research activities and were considered to be of limited analytic interest. Other addresses delivered by non-South Africans were excluded automatically on the assumption that only locally-based speakers would be able to speak authoritatively on the state of the discipline in South Africa. The data set, therefore, consisted of forty-five addresses spanning sixty-one years (1950-2011) and five associations (see Table 1, below). The earliest of these associations - the South African Psychological Association (SAPA) - was formed in 1948, the year of the National Party's (NP) shock electoral victory. In 1962, however, Afrikaner psychologists defected from SAPA on the question of black membership to create the Psychological Institute of the Republic of South Africa (PIRSA). But in 1978, with the apartheid state starting to unravel, the whites-only Institute started holding joint congresses with the racially integrated SAPA with which it would eventually reconcile - in 1982 - to form the Psychological Association of South Africa (PASA). A year later, the Organisation of Appropriate Social Services in South Africa (OASSSA) was established in protest against the perceived support of mental health professionals for the apartheid regime. By the late 1980s, the white-run OASSSA was deemed not radical enough by black psychologists who founded the Psychology and Apartheid Committee instead.1 With the inception of democratic rule in 1994, PASA, OASSSA and the Psychology and Apartheid Committee dissolved to form the Psychological Society of South Africa (PsySSA). Table 1 provides a tabular overview of the data set, by association and period.

In this study, addresses were discourse analysed in keeping with the models favoured by Fairclough (1992) and Wetherell and Potter (1992). Both approaches manage to reconcile "top-down" Foucauldian discourse analyses where "the subjects of history are replaced with rituals of power" (Wetherell & Potter, 1992: 86) with "bottom-up" analyses of the conversation analytic tradition "in which people are the active users of language" (Wood & Kroger, 2000: 24). That is, they succeed in viewing people as "simultaneously the products and the producers of discourse" (Edley & Wetherell, 1997: 206). The paradoxical quality of language-use is not cause for paralysis but edification - indeed, "the paradox is more convincing than its theoretical dissolution" (Billig, 1991: 9).

Since Wetherell and Potter (1992) consider discourse as both constitutive of and constituted by sociality, they emphasise the importance of social theory to discourse analysis. They forego the term "discourse", however, in favour of "interpretative repertoires" - defined as "broadly discernible clusters of terms, descriptions and figures of speech often assembled around metaphors or vivid images" (ibid.: 90). They argue that, unlike "discourse", the idea of an interpretative repertoire suggests "that there is an available choreography of interpretative moves - like the moves of an ice dancer, say - from which particular ones can be selected in a way that fits most effectively in the context" (ibid.: 92).

Fairclough, however, who includes in his three-dimensional model of critical discourse analysis a more fine-grained linguistic analysis of textual features, retains usage of the word 'discourse'. Nevertheless, his understanding is broadly consonant with that of Wetherell and Potter: "In using the term 'discourse', I am proposing to regard language use as a form of social practice, rather than a purely individual activity or a reflex of situational variables. This has various implications. Firstly, it implies that discourse is a mode of action, one form in which people may act upon the world and especially upon each other, as well as a mode of representation. Secondly, it implies that there is a dialectical relationship between discourse and social structure, there being more generally such a relationship between social practice and social structure: the latter is both a condition for, and an effect of, the former. On the one hand, discourse is shaped and constrained by social structure in the widest sense and at all levels ... On the other hand, discourse is socially constitutive ... Discourse contributes to the constitution of all those dimensions of social structure which directly or indirectly shape and constrain it" (Fairclough, 1992: 63-64).

Consequently, the present study sought not only to identify the discursive practices of speakers, but to describe the socio-political conditions within which these discourses took shape. Similar to Fairclough (1992), Wetherell and Potter (1992) underscore the importance of placing discourse in its proper context. Citing the work of the sociologist, John Thompson, they observe that "the analysis of ideology should involve three stages: first, the social scientist must describe the social field, history and social relations relevant to the area of investigation; then engage in some systematic linguistic analysis of the pattern of discourse; and finally, in an interpretative or hermeneutic act, connect the latter with the former" (Wetherell & Potter, 1992: 105).

In view of the size of the data set, it is not possible to present the results of the discursive and social analyses in all their complexity. Consequently, the contradictoriness of social talk that features strongly in the works of Potter and Wetherell is not a hallmark of this study, which tends to emphasise speakers' fidelity to particular discourses. Accordingly, it may appear as if a post-structuralist conception of discourse, descending from on high, has prevailed. Some readers may argue, therefore, that discourses seem to have emerged as if summoned, giving credence to the charge that, in discourse analysis, 'anything goes'. Others may imagine the understatement of didactic detail for the sake of historical narrativity to have led to an unintentional exchange of the actual discourses in the analytic material for the established discourses of history. Such concerns are not easily rebuffed, but it is countered that the analytic sections that follow, provide sufficient extracts from the data set to make a sound case to the contrary.

DISCOURSE ANALYSIS

In the fifties, SAPA's Afrikaner presidents expressed a concern for "social relevance" in the shape of a professionalist discourse that encouraged public service. They spoke variously of a service "gap the community feels increasingly with each passing day" ("...'n leemte wat daagliks al meer gevoel word deur die gemeenskap") (van der Merwe, 1958: 2), an associated imperative to protect a public that "is being shamelessly exploited by quacks and pseudo-psychologists of all kinds" (la Grange, 1950: 7), and "an unforgiveable sin against humankind" ("...'n onvergeeflike sonde teenoor die mensdom") (van der Merwe, 1958: 6) that would be committed should psychologists fail to assume their positions on multidisciplinary teams. Among English-speaking psychologists, by contrast, "relevance" was less of a priority in a discourse of disciplinarity concerned with the structure of the discipline. Anglophone psychologists were preoccupied with a "battle of the schools" (MacCrone, 1951: 8), a "dichotomy" between the clinical and the experimental (Pratt-Yule, 1953: 4) and a "dilemma" between pure and applied psychology (Biesheuvel, 1954: 134). Troubled by these "fundamental issues" (MacCrone, 1951: 8), they sought "perspective" (ibid.) and "liberal-minded pragmatism" (Pratt-Yule, 1953: 9).

By the early sixties, however, conservative Afrikaner psychologists would not countenance the prospect of a racially mixed association and split from SAPA to establish PIRSA. For most of the decade, the exclusively white Institute drew on a survivalist discourse of ethnic-national service in order to address "problems that are busy threatening on a large scale the foundations of our continued national existence" ("SIRSA [behoort] in die rigting te dink van planne te beraam vir hulpverlening veral met betrekking tot die. vraagstukke wat besig is om die fondamente van ons nasionale voortbestaan op groot skaal te bedreig.") (la Grange, 1962: 17). The Afrikaner volk (ethnic group) was constructed as vulnerable to the "dangerous joke" ("gevaarlike grap") of egalitarianism (Robbertse, 1967: 3), which necessitated "destroying] the faulty and dangerous image that the egalitarians have created" ("Op die realiste... rus die dure plig. om die foutiewe en gevaarlike beeld wat die gelykstellers... daargestel het... te help vernietig.") (ibid.: 4). Indeed, it was "[o]nly on the basis of a strong orientation of service to country and people [that] our survival [is] justified and our future assured" ("Slegs op die grondslag van 'n sterk motief van diens aan land en volk... is ons voortbestaan geregverdig en ons toekoms verseker.") (la Grange, 1966: 18).

But amid the political turmoil of the seventies, PIRSA's ideological fortitude crumbled as calls for research of "ethnic-national relevance" receded into the background. Instead, a discourse of benevolence emerged that appealed once more for research of general "social relevance". Some of PIRSA's new priorities included, inter alia, determining those characteristics that would assist the black South African "in his hour of crisis" ("in sy krisisuur") to cope with the demands of Western capitalism (Robbertse, 1971: 7) and developing a psychotherapeutic model that could address "the absurdity and meaninglessness" ("die absurditeit en doelloosheid") of the human condition (van der Merwe, 1974: 15). In fact, by the mid-seventies, one PIRSA president gave effect to the nihilism of the day by rounding on "social relevance", decrying psychological literature as "consisting of an endless set of advertisements for the emptiest of concepts, the most inflated theories, the most trivial 'findings'" (Koch, 1971 quoted in du Toit, 1975: 25). Even the Afrikaner ideal of public service through psychology was impugned: professional registration, it was alleged, had never been about protecting the public but, rather, practitioners themselves.

Despite attempts to restore ideological normality, PIRSA never recovered, fusing with SAPA in 1982 to form PASA. The joint SAPA-PIRSA (1978-1981) and, thereafter, PASA congresses continued their engagement with the notion of a "socially relevant" psychology, albeit across a trio of politically conservative discourses. According to one of these discourses, which was centered on the professionalisation of the discipline, the task at hand was that "[w]e should... with all our strength develop our profession to deliver the kinds of services to society by which we shall earn their respect" ("Ons moet... met al ons kragte ons professie ontwikkel om dié soort dienste aan die gemeenskap te lewer waarmee ons hulle respek sal verdien.") (Langenhoven, 1978: 14). This was to be achieved by asking oneself whether "the clinician trained in a mental hospital [was] equipped to deal with the cardiac patient in a general hospital or with a woman in a maternity home facing the birth of her first child... [or] with a child suffering from some kind of developmental delay..." (Gerdes, 1979: 4). Such deliberations would inform the further differentiation of the professional register. A second discourse of disciplinarity concentrated on fundamental questions rather than political ones, which were rendered via the depoliticizing logic of the discipline. Beneath this lens, the apartheid crisis was transformed into "the generality/specificity issue" (Gerdes, 1992: 40) with psychologists expected to content themselves with acquiring "[k]nowledge for the sake of understanding, not merely to prevail... [f]or if we fail to struggle and fail to think beyond our petty lot, we accept a sordid role" (Bush, 1959 quoted in Biesheuvel, 1987: 7). As for the third discourse of salvation, the quest for "social relevance" became an act of "atonement" (Strümpfer, 1993: 32) through which the discipline would earn the right to belong in "the new South Africa", ensuring thereby that "psychology will live on" (van der Westhuÿsen, 1993: 3).

By contrast, OASSSA's appraisal of a "socially relevant" discipline was embedded in a liberationist discourse in which "[t]he struggle for liberty is... transformed from being only a means to an end, to being an end in itself" (Coovadia, 1987: 1). Committed to working only with the victims of apartheid brutality, the organisation did not have a specific interest in cardiac patients, first-time mothers or "knowledge for the sake of understanding"; given the negative consequences of apartheid policy on mental health, it insisted that, "[i]n order to make South Africans more psychologically healthy and to resolve crises of mental health, we need to engage in politics" (Vogelman, 1986: 3). Whereas one of PASA's keynote speakers claimed that "demonstrat[ing] against apartheid will achieve little or nothing, apart from moral self-satisfaction on the part of the protesters" (Biesheuvel, 1987: 6), the opening speaker at one of OASSSA's congresses observed that professional organisations "have in the perception of both the people of this country and beyond, been seen to be too closely allied to the ideology and practices of the apartheid state and are therefore irrelevant to people's needs" (Coovadia, 1987: 15).

With palpable differences of opinion on the question of political engagement, there was no telling what would happen when, in 1994, PASA, OASSSA and the Psychology and Apartheid Committee disbanded to form PsySSA. To be sure, "social relevance" remained a core value of the new association; unexpectedly, however, its congresses would witness also the rise of a market rationality. Year after year, PsySSA's presidents and guest speakers deployed a market discourse that was concentrated on commercial interests, global competitiveness and the discipline's international standing. With one PsySSA president casting psychologists as "service providers" for "our clients" (Veldsman, 1996: 6), another emphasised the importance of "management teams" (Sibaya, 2004: 2), "foster[ing] productivity" (ibid.), "our core products" (3) and the need for "quality assurance" (ibid.). All the while, references to the country's past and present injustices animated a competing discourse of civic responsibility. Here, instead of psychologists bickering over "the sub-20% of the population who are on medical aid or hospitalised" (Tlou, 2011: 2), the focus was redirected to "the rest of the population we could be serving" (ibid.). The discipline's proper business was to produce "enlightened and critical South African and African citizens" (Badat, 2002: 11) capable of "engag[ing] with the ideologies of neo-liberalism and privatisation" (ibid.: 12-13). It was asserted that, "[i]f in our deliberations we miss the discourse around the plight of the masses of our people and how this discipline ought to impact them in a positive way, I want to submit that we will be a discipline that may stand accused of existential irrelevance" (Mkhize, 2007: 7).

SOCIAL ANALYSIS

It is apparent that "relevance" has meant different things to different generations of South African psychologists. Advanced by politically conservative, progressive and radical psychologists alike, there is little about "relevance" that can be taken for granted: it is not a politically neutral construct but, as this section will make evident, is rooted in the ideological currents of the day.

Afrikaner psychologists of the 1950s understood "relevance" in terms of professionalisation - conversely, for their Anglophone colleagues who were concerned mainly with the structure of the discipline, it was a relative non-issue. What is striking, however, is the nonappearance of ethnic-national discourse in the addresses of SAPA's Afrikaner presidents, especially given its preponderance in the first decade of PIRSA's existence. With an Afrikaner government ruling the country since 1948, one would have expected more ideological forthrightness in the addresses of these presidents. That one does not, is a reflection of the then ruling NP's desire to expand its political base. There was little likelihood of an Afrikaner republic with a five-seat parliamentary majority when the United Party had won the popular vote by some margin. Moreover, because Prime Ministers D F Malan (1948-1954) and J G Strijdom (1954-1958) "were determined to keep the nationalist policy agenda firmly in the party's hands" (O'Meara, 1996: 47), the Broederbond - a secret society of Afrikaner men that presided over the formulation of Christian-National dogma - ended up being sidelined for much of the 1950s. So, too, in the discipline, the absence of ideology among leading Afrikaner psychologists mirrored the goings-on among their political masters -not mentioning the practical matter of professional registration, which required cooperating with their Anglophone colleagues. As for English-speaking psychologists' advocacy of circumspection, "perspective" and "liberal-minded pragmatism", it is not that they were indifferent to the social problems of the day but that they placed their faith in science itself - that is, in "the hope that reasoned enquiry and patient persuasion would triumph over 'ideology'... [in] an increasingly race-obsessed state" (Dubow, 2001: 116). This was typical of "liberals in the post-1948 era [whose] insistence on reason and moderation was, perhaps, a comfortable and comforting position to adopt - because it allowed those in the beleaguered middle ground to cast their opponents as extremists" (ibid.).

When interpreting PIRSA addresses - particularly the progressive unravelling of the Institute's ideological coherence - an examination of the socio-political currents of those years proves equally illuminating. In respect of the addresses of the sixties, the heady years following the declaration of a republic in 1961 made it possible for PIRSA presidents to deploy a discourse of ethnic-national service (volksdiens) in its pursuit of "ethnic-national relevance". By the start of the seventies, however, the fragility of the apartheid project was starting to show. The attainment of the republican dream ended up mitigating, paradoxically, the appeal of ethnic-national discourse by weakening the hold of the now vanquished "British bogeyman" (O'Meara, 1996: 116) over the collective imagination of Afrikaners. Economic progress and a growing cultural liberalism exploited the lacking sense of mission and precipitated a splintering of the volk (O'Meara, 1996; Giliomee, 2003), while the contrasting leadership styles of H F Verwoerd (1958-1966) and B J Vorster (1966-1978) put an end to the days of ideological certitude. With Grand Apartheid having lost the plot, PIRSA's eventual collapse was only a matter of time.

As for the joint SAPA/PIRSA and, later, PASA congresses, the political indifference on display at a point in South African history described as "apartheid's most brutal period" (Louw, 2004: 83) is scarcely believable. At a time when Steve Biko had just been killed, young white men were being forced into military service, the African National Congress (ANC) was bombing SASOL installations, white professionals were starting to leave the country in droves, South Africa was under an arms embargo and the economy was in recession (Beck, 2000), not a single speaker was able to mention the word "apartheid" except for Biesheuvel in 1986. By then, tricameralism had failed, rebellion in the townships had been brutally suppressed, hundreds of thousands of workers and students had embarked on a boycott campaign, disaffected comrades were "necklacing" suspected collaborators and the country was now in the grip of a national state of emergency (Louw, 2004). In the meantime, SAPA/PIRSA/PASA talk of general systems theory (Gerdes, 1979; Rademeyer, 1982; Raubenheimer, 1981) - convinced of its suitability for the national situation - was articulated in technicist ways more befitting the theory's cybernetic origins.

How this state of affairs came about had much to with the fact that, between 1978 and 1983, a "new language of legitimation" (Posel, 1987: 419) started to emerge in official state discourse. The ideological fidelity of the years of Verwoerdian orthodoxy gave way to a supposedly apolitical discourse of "effectiveness" that was built on notions of "technocratic rationality, 'total strategy' and 'free enterprise'" (ibid.: 420). By depoliticizing any given state intervention and rendering it incontestable, Prime Minister P W Botha's (1978-1984) "discourse of Total Strategy... encouraged the spread of a new technocratic managerialism throughout the wider white South African society. Government, business, educational institutions, the media - seemingly the entire establishment - became infected by this craze for technocratic rationality" (O'Meara, 1996: 269). One observes, correspondingly, the fall of ideology in SAPA, PIRSA and PASA addresses from the late seventies onwards. The diminishing incidence of political referents evident in PIRSA addresses of the early and mid-seventies resulted from multiple crises within Afrikanerdom but the continuation of that trend into the eighties was the outcome of the staged death of politics in national (white) discourse. Of course, it may be countered that the prominence of professionalist discourse in SAPA/PIRSA/PASA circles had less to do with their co-option by an increasingly technocratic state than with the establishment of the first Professional Board for Psychology in 1974. And yet their depoliticised order of discourse coincided with a decline in both scientific and political papers on "race" in the South African Journal of Psychology - their official journal (Durrheim & Mokeki, 1997). The attempt to dispense with politics was not due to professionalising forces inside the discipline or because of any particular desire to steer clear of troubled waters - rather, "P W Botha's attempts at a policy of 'non-racialism' during the early 1980s may have... [made] a race focus seem irrelevant" (ibid.: 211).

While PASA's politically conservative congresses continued, those who had not been interpellated by professionalist discourse were marching to the beat of a different drum. OASSSA - a self-avowed "political organisation which... situates itself within the mass democratic movement" (Anonymous, nd: 2) - was pursuing a liberationist line. Speakers such as Vogelman and Coovadia belonged to the United Democratic Front (Andrew Dawes, personal communication, December 21, 2012), a Charterist front for the banned ANC. Admittedly, the UDF meant "different things to different people" (Louw, 2004: 150): founded in 1983 in opposition to Botha's tricameral reforms, the non-racial coalition of hundreds of civic, women's, youth and religious organisations succeeded in "fudging its discourse" (ibid.) to generate a constituency spanning much of the political spectrum. Nonetheless, the Front was clearly a source of inspiration for OASSSA whose engagement with the repressive politics of the day could not have been more removed from PASA's comparative dithering.

As regards the post-apartheid years, the prominence of a market discourse at PsySSA congresses is a testament to the global reach of a market rationality that has infiltrated the political, economic and higher education landscapes of democratic South Africa. The end of isolation permitted the country's rapid assimilation into an already globalised neo-liberal order; in fact, already in the early nineties the once socialist-leaning ANC had been converted to the so-called "Washington Consensus" thanks to the efforts of diplomats, the corporate sector, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank (Louw, 2004). Granted, the ANC did unveil an interventionist Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) as its 1994 election manifesto -but only after having signed a secret protocol on economic policy endorsing trickle-down economics (Terreblanche, 2002). This explains why, two years after winning the elections, the Ministry of Finance announced a new macroeconomic strategy called Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR), which, "decorated with all the trimmings of globalisation, ... represent[ed] an almost desperate attempt to attract [foreign direct investment]" (ibid.: 114).

The South African academy was not immune to these powerful market forces either. In the final quarter of the twentieth century, a new regime of knowledge production arose, the result of increased economic competition within a globalising world economy, escalating requirements of postindustrial technoscientific society and declining public funding of universities (Slaughter & Leslie, 1997). On campuses the world over, the ensuing capitalisation of knowledge led to a proliferation of behaviours associated more commonly with the market, while, in South Africa specifically, leading educationists encouraged the implementation of the new dispensation (Jansen, 2002). Consequently, it becomes difficult to imagine the country's present-day psychologists - as the products and functionaries of these higher education institutions - ignoring the "relevance" of market considerations. Indeed, psychologists around the world "understand the demands of neo-liberalism and capitalism all too well and are eager to make themselves useful once again as consultants for the New World order" (Painter, 2012: paragraph 28).2

CONCLUSION

The foregoing analyses suggest an historical affinity between "relevance" and prevailing socio-political conditions. However, the study also suffers from an important limitation that must be acknowledged: there are, specifically, three discernible gaps in the data set that limit the validity of the study's findings. The first pertains to the virtual absence of SAPA addresses during the 1960s and 1970s, leaving important historical questions unanswered. In what terms did SAPA view its mission at a time when PIRSA was advancing a discourse of ethnic-national service? And how did SAPA position itself when the apartheid regime started to decline? Certainly, every effort was made to locate the SAPA archives. Unfortunately, reports that PsySSA and/or the University of the Witwatersrand were in possession of these documents turned into blind alleys, as did conversations with several SAPA members. Then again, it is something of an open question whether a significant number of addresses from the 1960s and 1970s ever existed: according to the final newsletter of SAPA's Western Cape branch, "[i]f the 1960's were generally characterised by a low but consistent degree of SAPA activity, the lowest point was reached in 1979 when only a single meeting was held" (Foster & Levett, 1983: 1).

A second gap relates to addresses delivered at congresses of the Psychology and Apartheid Committee. Despite the fact that only two such addresses were sourced, a case can be made that the contributions of these non-South African speakers would have conveyed at least some sense of the Committee's ethos. Consequently, it can be argued that the decision to exclude these addresses from the analysis weakens it in some sense. On a separate note, when one considers the crucial role played by the Psychology and Apartheid Committee in confronting the racism of South African psychology, it is of concern that a substantive history of the Committee has yet to be written.

The third gap centres on a noticeable lack of PASA and PsySSA presidential addresses: in many instances, speeches had been misplaced, discarded or were never committed to paper in the first place. Moreover, at PsySSA congresses it was observed how it became increasingly common for non-psychologists to deliver opening and keynote addresses. This raises the additional question of whether non-office bearing speakers are in a position to comment on the state of the discipline in South Africa. On the other hand, when non-psychologists raise the same issues as psychologists themselves, their 'outsider' status becomes less significant. Nonetheless, the paper has attempted as far as possible to provide excerpts from the speeches of psychologists, with the exceptions of passages drawn from Coovadia (1987), Badat (2002) and Mkhize (2007).

Despite its limitations, this study has revealed the creeping influence of the market over South African psychology congresses. Given the country's - and the discipline's -ongoing commitment to transformation imperatives, this presents a stark contradiction that threatens to reverse the gains made by critical psychologists. If one takes seriously the notion of the constitutiveness of discourse, then additional studies are required that will examine further the discursive practices of psychologists, whether these are located in monographs, journal articles or - as in the case of this study - conference proceedings. Whereas appeals for "social relevance" were prominent during the 1980s when resistance to apartheid rule was at its peak, "market relevance" has become important in the post-apartheid era. While there are many who will claim that we have entered a moment in world history when the "economic imperative . will sweep all before it" (Singh, 2001: 20), this does not signify necessarily a shift in the local order of discourse. At a time when the universalist promise of cognitive science is proving especially alluring, arguments about "social relevance" are likely to persist. For, if the history of "relevance" reveals anything, it is that psychologists turn to "relevance" when the discipline turns to science.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, R & Pillay, A L (2004) Reviewing clinical psychology training in the post-apartheid period: Have we made any progress? South African Journal of Psychology, 34(4), 630-656. [ Links ]

Anonymous (nd) What is OASSSA? Mayibuye Archive, Main Library, University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Badat, S (2002) Challenges of a changing Higher Education and social landscape in South Africa. Speech presented at the 8th South African Psychology Congress, Cape Town, South Africa. [ Links ]

Beck, R B (2000) The history of South Africa. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. [ Links ]

Biesheuvel, S (1991) Neutrality, relevance and accountability in psychological research and practice in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 21(3), 131-140. [ Links ]

Biesheuvel, S (1987) Psychology: science and politics. Theoretical developments and applications in a plural society. South African Journal of Psychology, 17(1), 1-8. [ Links ]

Biesheuvel, S (1954) The relationship between psychology and occupational science. Journal for Social Research, 5, 129-140. [ Links ]

Billig, M (1991) Ideology and opinions: Studies in rhetorical psychology. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Calhoun, C (1998) The public good as a social and cultural project, in Powell, W W & Clemens, E S (eds) (1998) Private action and the public good. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Cooper, S & Nicholas, L J (2012) An overview of South African psychology. International Journal of Psychology, 47(2), 89-101. [ Links ]

Coovadia, J (1987) Social service professionals as agents of structural change in South Africa (pp11-31), in OASSSA, & Hansson, D (eds) (nd, [1988]) Mental health in transition. Proceedings of the Second OASSSA National Conference. Cape Town: OASSSA. [ Links ]

Dawes, A (1986) The notion of relevant psychology with particular reference to Africanist pragmatic initiatives. Psychology in society, 5, 28-48. [ Links ]

du Toit, J M (1975) Sielkunde - Die wetenskap van die lewe? Speech presented at the 14th annual meeting of the Psychological Institute of the Republic of South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Dubow, S (2001) Scientism, social research and the limits of "South Africanism": The case of Ernst Gideon Malherbe. South African Historical Journal, 44(1), 99-142. [ Links ]

Durrheim, K & Mokeki, S (1997) Race and relevance: A content analysis of the South African Journal of Psychology. South African Journal of Psychology, 27(4), 206-213. [ Links ]

Edley, N & Wetherell, M (1997) Jockeying for position: The construction of masculine identities. Discourse and Society, 8(2), 203-217. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N (1992) Discourse and social change. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Foster, D & Levett, A (1983) Final Newsletter. Cape Town: South African Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Gerdes, L (1992) Impressions and questions about psychology and psychologists. South African Journal of Psychology, 22(2), 39-43. [ Links ]

Gerdes, L (1979) Perspectives, issues and the need for a history of psychology in South Africa. Speech presented at the 2nd joint congress of the Psychological Institute of the Republic of South Africa and the South African Psychological Association, Potchefstroom, South Africa. [ Links ]

Giliomee, HB (2003) The Afrikaners: Biography of a people. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Hessels, L K, van Lente, H & Smits, R (2009) In search of relevance: The changing contract between science and society. Science and Public Policy, 36(5), 387-401. [ Links ]

Holdstock, T L (1981) Psychology in South Africa belongs to the colonial era. Arrogance or ignorance? South African Journal of Psychology, 11(4), 123-129. [ Links ]

Jansen, J D (2002) Mode 2 knowledge and institutional life: Taking Gibbons on a walk through a South African university. Higher Education, 43(4), 507-521. [ Links ]

la Grange, A J (1966) Resente bydraes van sielkundiges (met spesiale verwysing na SIRSA-lede) t.o.v. dringende vraagstukke op die gebied van padveiligheidsnavorsing en die bestryding van padongelukke. Monographs of the Psychological Institute of the Republic of South Africa, 44, 1-18. [ Links ]

la Grange, A J (1962) Die agtergrond en die vernaamste taakstelling van SIRSA. PIRSA Proceedings, 1, 7-18. [ Links ]

la Grange, A J (1950) Summary of the presidential address. SAPA Proceedings, 1, 7-8. [ Links ]

Langenhoven, H P (1978) The registration of psychologists. Speech presented at the joint congress of the Psychological Institute of the Republic of South Africa and the South African Psychological Association, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

Louw, P E (2004) The rise, fall, and legacy of apartheid. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. [ Links ]

MacCrone, I D (1951) Perspective in psychology. SAPA Proceedings, 2, 8-11. [ Links ]

Macleod, C & Howell, S (2013) Reflecting on South African Psychology: Published research, "relevance", and social issues. South African Journal of Psychology, 43(2), 222-237. [ Links ]

Mansbridge, J (1998) On the contested nature of the public good, in Powell, W W & Clemens, E S (eds) (1998) Private action and the public good. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Mkhize, B (2007) Opening address. Speech presented at the 13th South African Psychology Congress, Durban, South Africa. [ Links ]

Nell, V (1990) One world, one psychology: "Relevance" and ethnopsychology. South African Journal of Psychology, 20(3), 129-140. [ Links ]

O'Meara, D (1996) Forty lost years: The apartheid state and the politics of the National Party, 1948-1994. Randburg: Ravan Press. [ Links ]

Painter, D (2012) Van "ken" jouself na "bemark" jouself. http://m.news24.com/beeld/By/Nuus/Van-ken-jouself-na-bemark-jouself-20120803. [ Links ]

Pillay, A L & Siyothula, E B (2008) The training institutions of black African clinical psychologists registered with the HPCSA in 2006. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(4), 725-735. [ Links ]

Posel, D (1987) The language of domination, 1978-1983, in Marks, S & Trapido, S (eds) (1987) The politics of race, class and nationalism in twentieth-century South Africa. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Pratt-Yule, E (1953) The clinical approach to the study of behaviour. Opening address. SAPA Proceedings, 4, 4-9. [ Links ]

Rademeyer, G (1982) Creative interpersonal relationships. Speech presented at the National Psychology Congress, Bloemfontein, South Africa. [ Links ]

Raubenheimer, I v W (1981) Psychology in South Africa: Development, trends and future perspectives. South African Journal of Psychology, 11(1), 1-5. [ Links ]

Robbertse, P M (1971) Sielkundige navorsing en Bantoetuislandontwikkeling. South African Psychologist, 1(1), 2-9. [ Links ]

Robbertse, P M (1967) Rasseverskille en die sielkunde. Monographs of the Psychological Institute of the Republic of South Africa, 72, 1-12. [ Links ]

Sibaya, P T (2004) PsySSA presidential address. Speech presented at the PsySSA 10th Anniversary Congress, Durban, South Africa. [ Links ]

Singh, M (2001) Re-inserting the "public good" into higher education transformation. Kagisano Higher Education Discussion Series, 1, 7-22. [ Links ]

Slaughter, S & Leslie, L L (1997) Academic capitalism: Politics, policies and the entrepreneurial university. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Sokal, M M (1992) Origins and early years of the American Psychological Association, 18901906. American Psychologist, 47(2), 111-122. [ Links ]

Strümpfer, D J W (1993) A personal history of psychology in South Africa. Speech presented at the annual congress of the Psychological Association of South Africa, Durban, South Africa. [ Links ]

Terreblanche, S (2002) A history of inequality in South Africa, 1652-2002. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press. [ Links ]

Tlou, E (2011) PsySSA presidential address. Speech presented at the 17th South African Psychology Congress, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

van der Merwe, A B (1974) Die mediese model in die sielkunde. Monographs of the Psychological Institute of the Republic of South Africa, 165, 1-20. [ Links ]

van der Merwe, A B (1958) Die kliniese sielkundige en geestesgesondheid. SAPA Proceedings, 9, 2-6. [ Links ]

van der Westhuÿsen, B (1993) Acceptance of presidency. Speech presented at the annual congress of the Psychological Association of South Africa, Durban, South Africa. [ Links ]

Veldsman, T H (1996) Creating out of the present the future. Speech presented at the second annual general meeting of the Psychological Society of South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Vogelman, L (1986) Apartheid and mental health. Speech presented at the first national conference of the Organisation for Appropriate Social Services in South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Wetherell, M & Potter, J (1992) Mapping the language of racism: Discourse and the legitimation of exploitation. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf. [ Links ]

Wood, L A & Kroger, R O (2000) Doing discourse analysis: Methods for studying action in talk and text. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author

1 Two keynote addresses from Psychology and Apartheid Committee congresses were located but were excluded from the data set on the grounds that they were delivered by non-South Africans. The data set, therefore, was restricted to addresses delivered at SAPA, PIRSA, PASA, OASSSA and PsySSA congresses.

2 Translated from the original Afrikaans.