Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Psychology in Society

versão On-line ISSN 2309-8708

versão impressa ISSN 1015-6046

PINS no.43 Stellenbosch Jan. 2012

ARTICLES

Working with historicity: tracing shifts in contraceptive use in the activity system of sex over time

Mary van der Riet

Psychology, School of Applied Human Sciences. University of KwaZulu-Natal. Pietermaritzburg. vanderriet@ukzn.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Sexual activity, sexuality and responses to HIV and AIDS in a rural context in South Africa were studied using a cultural-historical activity theory framework. Activity theory directs the focus onto activity and emphasises the importance of an historical perspective for understanding current preventative practices. Qualitative data were generated from interviews and focus groups with 45 male and female participants between 10 and 71 years of age. An activity system analysis illustrated critical historical changes in a mediational artefact (the form of contraception) in sexual activity. The shift from intercrural sex to the use of the injectable contraceptive set up particular conditions for condom use in response to HIV and AIDS.

Keywords: Cultural-historical activity theory, historicity, HIV, injectable contraception, condom use

INTRODUCTION

HIV and AIDS is a significant global problem, but particularly for South Africa which has more people living with HIV than any other country in the world (UNAIDS, 2011). At an estimated 5.6 million, the South African epidemic is only beginning to stabilise. Understanding why behaviour does not change in response to the risk of HIV and AIDS is a critical task. Sexual activity, sexuality and responses to HIV and AIDS were studied in a rural context in South Africa using a cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) framework (Van der Riet, 2009). The research sought to understand why, in the face of the risk of HIV and AIDS and armed with knowledge of HIV and the means to engage in prevention of infection, youth still engaged in risky sexual activity. This article reports on an aspect of the activity system analysis of the data, focussing particularly on changes over time in the mediational artefact of the form of contraception in the activity system of sexual activity. Changes in this mediational artefact have established particular dynamics for condom use in a context of HIV and AIDS.

CULTURAL-HISTORICAL ACTIVITY THEORY

CHAT, or activity theory, is a set of philosophical and methodological assumptions about framing and investigating psychological problems. It has roots in the writing of Marx and Engels, and in the Soviet Russian cultural-historical psychology of Vygotsky, Leontiev and Luria (Roth & Lee, 2007). A core assumption is that humans are constituted by their practical activity, in particular by "... participation in social and historical practices" (Tolman, 2001: 91). This means that any analysis of human behaviour should be grounded in a concrete examination of the dynamics of practical social activity instead of the actions or the cognition of an individual, which is often the case in the study of health behaviour. Following activity theory, human practices (such as sexual practices), and human agency, are analysable only in relation to the activity of which they are a part. In addition to this, activities are not isolated entities but part of "broader systems of relations in which they have meaning" (Lave & Wenger, 1991: 53). Daniels (2001: 86) argues that activity is a "collective, systemic formation that has a complex mediational structure". Understanding human behaviour therefore requires a focus on systems of activity.

THE STUDY

Research on sexual activity, sexuality and responses to HIV and AIDS was conducted in villages in a rural area in South Africa. Sexual activity contains the typical practices which occur repeatedly between partners which potentially lead to the transmission of HIV. The activity system of sexual activity thus formed the unit of analysis in this study.

The research site was an impoverished area with only basic services (electricity but no running water; a few primary schools but only one secondary school; a clinic but no police station), very few employment opportunities and the nearest town 25 km away on a gravel road. The study was explained to potential participants at a broad community meeting in the research site. Using a purposive, convenience and age stratified sample, individuals from 10 to 71 years of age were then approached to participate in the study. Participants under the age of 18 were informed of the study verbally and in writing and were only involved in focus group discussions if they assented to this, and if their guardians had also provided consent. Once they had given their consent to participate, the 27 female and 18 male participants were then individually interviewed, or participated in focus group discussions, on sexual activity and their response to HIV and AIDS, which were audio-recorded. The identity of all study participants was kept confidential through ascribing a code to each participant. The discussions were then translated (if in isiXhosa) and transcribed by the author and research assistants in preparation for data analysis.

ACTIVITY SYSTEM ANALYSIS

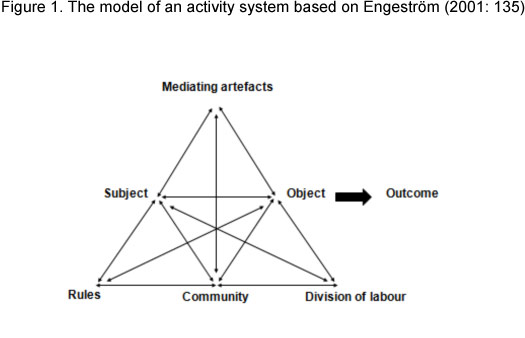

To analyse activity Engestrom (1987: 81) has developed a model of human activity which he argues is the "smallest and most simple unit that still preserves the essential unity and integral quality behind any human activity" but enables a focus on the systemic relations between the individual and the outside world. In the activity system (depicted graphically in Figure 1) an activity is the engagement of a subject towards a certain goal or object. The activity system thus includes the subject (the individual whose agency is chosen as the point of view in the analysis); the object or focus of the activity driven by a motive; the outcome of the activity; and tools (physical and, or conceptual instruments which mediate the activity). Engestrom (1987) argues that human activity is also always organised, constrained and governed by a division of labour, by rules, and by the individual's membership of a particular group of people (community) and these components are included in the lower half of the triangular model of the activity system.

An activity system analysis involves looking at the system as if from "above", and then also selecting a member of the local activity (a man or a woman) through whose eyes and interpretations the activity is constructed. For example, using the triangular model of the activity system the data was analysed for critical mediators of the activity (such as the physical tools which operated in the system, also referred to as mediational artefacts); the dominant rules, norms and conditions which governed the participants' experiences of sexual activity; the community or main reference point for each of the subjects; and the division of labour in the activity (roles and responsibilities in sexual activity; and power, status, and gender dynamics in the sexual activity), in relation to the subject's view.

Activities and activity systems also develop over long periods of time through the use of cultural resources such as historically formed mediating artefacts common to the broader society (Engeström & Miettinen, 1999). History is thus inevitably present in the activity system and it permeates current practices. In fact Engeström (1987) argues that in order to understand human behaviour (for example, young people's lack of response to HIV as a significant risk), an historical perspective is essential. Engeström (1999: 26) proposes the activity system as the appropriate unit of analysis which facilitates an historical perspective: "If the unit is the individual or the individually constructed situation, history is reduced to ontogeny or biography. If the unit is the culture or the society, history becomes very general or endlessly complex. If a collective activity system is taken as the unit, history may become manageable, and yet it steps beyond the confines of individual biography". Working with historicity thus enables a perspective on the individual-social dialectic.

In the study an historical account of sexual activity was obtained through a reading of historical and anthropological accounts of sexual socialization in contexts similar to that in which the research was conducted, that is, the rural Eastern Cape (Hunter, 1936; Mayer & Mayer, 1970; Delius & Glaser, 2002). Although these accounts are embedded in the wider ideological narratives of the time and have been criticised (for example, for reflecting a particular construction of African sexuality in a "golden age"), they allow for a broad contextualisation of practices, revealing and exposing historical tensions and contradictions in sexual activity which affect the current nature of sexual activity. An historical form of the activity system was generated using these accounts and the rich personalised accounts of the older research participants born between 1930 and 1973. This artificial historical periodisation was useful in understanding the development of the current phase of the activity system. Data from the research participants born after 1973 were used to generate a current form of the activity system.

FINDINGS

The findings of the study are presented using an historical and a current form of the activity system assuming the perspective of a young man and a young woman as the subject of the system. Extracts from the data are used to illustrate the emergent tensions within, and between, components of the activity system. The extracts are prefaced with 'f' for female or 'm' for male participant, and then the participant's age if known, or their age category. For example, f49 is a female participant, 49 years of age. Participants over the age of 55 but whose exact age was unknown are referenced 55+. FG is used to indicate extracts from focus groups with the age group of the participants (eg FG16-25). Pauses in the extracts, or omissions in the transcript are indicated by Explanatory notes are indicated with square brackets: [ ].

Sexual activity historically

Older research participants comment on the taboos and restrictions around sexual activity. For example participant m56 was threatened with severe consequences should he touch a young woman in the genital area: "We were told that you would have a disease. You would be abhorrent, detestable, if you did. You would develop acne and no-one would like you. There was no chance to wash your hands to prevent disease. You absolutely shouldn't touch her there."

In the activity system these prohibitions on sexual activity form part of the implicit and explicit rules, norms and conventions that constrain actions and interactions with the activity system in response to the problematic outcome of sexual activity, namely, pregnancy. Historically premarital pregnancy was an extremely shameful experience leading to ridicule, public humiliation and social isolation. The young woman was held to have disgraced both herself and her companions, and they collectively entered a period of "mourning" (Hunter, 1936). In the research context premarital pregnancy was dealt with publicly and had severe consequences for both male and female partners and their families. Participant f53 comments: "When one got pregnant, then you were isolated from the other girls. They would run away from you Participant f55 said that if a young woman became "injured" they would "go into mourning on her behalf. We would stay for about two weeks without meeting our boys ... There would be concern all round and the parents would be stricter."

Pregnancy was a problematic outcome of sexual activity because child-bearing creates shifts in the way that a social group relates by affecting lineage, inheritance rights and therefore access to land and resources (Caldwell, Caldwell & Quiggin, 1989). In the research context lineage and inheritance rights passed through the paternal line and were managed through the formal recognition and regulation of relationships between men and women. Marriage involved the transfer of bride-wealth in form of cattle known as the payment of lobola. This allowed both men and women to gain status and fulfilled a social and economic role of securing access to property, resources and support (Hunter, 1936). It also ensured that the male lineage had rights over the children. Premarital pregnancy threatened this system and was heavily penalised.

Many of the participants referred to financial penalties related to premarital pregnancy. Participant m55+ comments: "you should never ever play inside [engage in penetrative intercourse] because your family might be fined cattle for that". Participant m55+ comments that he was aware that "the mistake of playing inside is taking the ... family's wealth in the form of cattle". For the young man, the cost was to the family and particularly the father who was required to pay "damages" to the family of the impregnated young woman. Hunter (1936: 183) comments that: "If the girl was found to have lost her virginity, the man with whom she was known to have slept before the examination [virginity test] was held responsible and he or his father had to pay a fine in cattle, usually five head if pregnancy resulted, three head if the girl did not become pregnant." Some participants mentioned an additional penalty paid by the young man directly to the mother of the young woman. Participant f53 says: ". there was also a goat, as a penalty fee, because you have sinned against the mothers, because they are the ones who are looking after the girls, and now you have damaged all that ...". Kaufman, de Wet, and Stadler (2001) argue that this fine was for disrespectful behaviour and a form of compensation for the impact a pre-marital pregnancy would have on the lobola payment. The young mother's family was also entitled to economic support for the child. The young man and his family thus carried the greater financial cost of the consequences of sexual activity.

The older participants also referred to an elaborate process called isihewula (a reference to an "alarm"), in which the male partner was socially castigated by a group of people in the community and a fine was levied. In this process "the women would go to the boy's home to report that the boy had damaged their child. This was done publicly ... The womenfolk would lodge a complaint and then a cow, a large one, or a sheep, would be chosen for the women to take home. The cow would then be slaughtered, not in the usual way, but below the kraal" (m56). The financial and social consequences for causing a pregnancy thus extended beyond the individual partners to their families.

In response to the risk of premarital pregnancy fathers took on the role of talking to their sons and were active in the regulation of sexual activity. Participant m56 commented: "When you were at a certain age, the father would tell you not to sleep with girls as they did not want any extended families to contend with". Mothers took responsibility for talking about sex with their daughters particularly at the onset of menstruation and when they began to show an interest in young men. Participant f36-45 comments: "... And when my mother noticed that I had... started menstruating, she called me and asked me if I have got a boyfriend. And I said 'Yes'. ... And then my mother said, 'When you sleep with a boy, never take off your panties, because then you will get pregnant'."

The activity system of sexual practice was thus historically governed by clearly articulated sanctions and prohibitions on penetrative sex. The consequences of premarital pregnancy were severe and the "subjects" of the activity system were well aware of these costs. Historically the tension between being sexual active and these prohibitions was managed through several processes which regulated sexual activity in relation to procreation. These included encouraging limited forms of sexual release through specific sexual techniques and instituting controls such as virginity testing (Hunter, 1936; Mayer & Mayer, 1970; Caldwell et al, 1989; Delius & Glaser, 2002).

Mechanisms for the regulation of sexual activity

Historically the tension between sexual desire and the negative consequence of pregnancy was resolved through maintaining a "barrier" to penetrative sex in the form of intercourse without full penetration (Mayer & Mayer, 1970). Many of the older research participants referred to this intercrural sex as ukumetsha, a practice which retained technical virginity (Mayer & Mayer, 1970) and prevented pregnancy. Participant f36-45 says that sex was restricted to playing "on the thighs" rather than "real sex". She and her peers used to discuss: "if you sleep with a boy you should be careful that he does not 'urinate' inside you, because if you let him do that you might get pregnant". Participant f49 refers to it as the "only contraceptives that were there then". Participant f55 says: "... you could allow a man to go as far as the thighs, but no penetration was allowed. We all understood this and we used to talk about it. We all knew that the danger was in becoming pregnant, so we were trying to avoid this at all costs. You would actually feel this wetness on your thighs and you would know that the man has ejaculated, but you wouldn't allow him to have real sex with you."

Male youth were cognisant of the need to limit sexual practices, not pressurising their female partners to go beyond thigh sex. Participant m55+ comments: "whenever I played with a girl, we played on the thighs . I would never play inside". Participant m56 says they were "afraid to do the wrong thing . we were sympathetic to their cause". Participant f55 comments that "even when he got you the boy would not say that you should open your thighs. If you had your thighs closed then he would accept that". Participant m71 says: "we were careful not to have any production between us two". Fear of pregnancy constrained sexual activity and acted as a deterrent to penetrative sex for both male and female partners. In the activity system intercrural sex was thus a tool mediating sexual activity and in the "division of labour" of this activity system, both male and female partners took some responsibility for the risks related to the activity.

In another form of the monitoring and management of sexual activity historically young girls and women were regularly examined to ensure adherence to the ukumetsha practice. The formally organised virginity inspections1 involved a physical examination of the vagina and hymen to "see" whether penetrative sex had taken place (Hunter, 1936) and determine whether these girls were virgins (Leclerc-Madlala, 2003). Loss of virginity before marriage was severely sanctioned because it led to a loss of value in the future lobola price and undermined a young woman's (but not a young man's) chances of marriage (Mayer & Mayer, 1970).

The older participants commented that if a young woman became pregnant "It would be quite a tough period in that there would be [virginity] inspections with parents wanting to know whether or not we were ourselves in trouble" (f55). Participant f53 comments:

" . . . even if you would have played a hard game where you would have sexual intercourse and you were not pregnant, you were being checked by the women. And they would tell that this girl she has done it, and she is wrong ... There were times when older mothers would come together and all girls would be taken to a place and that is when they would check that they were still girls, altogether...They would put something, a cloth or blanket down, and then a girl would sit on that and then open up her thighs and then they would see how the sexual parts are." The threat of virginity inspections clearly regulated behaviour in the sexual interaction, particularly constraining the activities of the male partner. Participant m56 refers to this "inspection" by older women: "... girls used to be inspected then by elderly women so that if she'd done things the wrong way [had sex], you [the boy], would be in trouble. We were afraid to do the wrong thing .... We knew that if girls had real se x... if a man penetrated, then the old women would see this and would want to know who had done this to the girl and she would be obliged to tell ... "

However, Mayer and Mayer (1970) comment that the escalating number of premarital pregnancies during this time period illustrated how the prohibitions on full intercourse were increasingly disregarded. Participant f35 says that there was no thigh sex "it was just straight sex, right from the start". Participant m43 argued: "No, no, no it was actual sex with full penetration. It was the real thing. We were aware that there was supposed to be no penetration, but ja we used to have actual sex with full penetration. And the non-penetrative kind of sexual activity was, you know, something from when we were still young."

These changes in sexual activity have been partly ascribed to the impact of the apartheid system which governed where people could live and work (Delius & Glaser, 2002). Various land Acts in the 1930s and apartheid policies in the 1960s governing the management of black residential areas had a significant effect on everyday life. Increased population pressure and untenable living conditions in the rural homelands (designated residential areas for African people, such as the site of this study), led to migrant labour and urbanisation. These processes undermined the fabric of African social life by eroding family structures, parental authority and traditional patterns of social interactions and controls (Klugman, 1993). This caused radical changes in the monitoring and management of sexual behaviour. The custom of ukumetsha was regarded as unfashionable and penetrative sex was expected (Delius & Glaser, 2002). The comment of one participant who had worked as a migrant labourer in an urban area illustrates what Burman and van der Spuy (1996) argue was the weakening of traditional sanctions on sexual intercourse under conditions of urban life. The participant m51 said: "Things were changing and you could hear it from your friends, especially those who were coming from the townships2... they would tell you 'This is an old thing that you are doing. We are no longer doing that. We are going directly to intercourse, not just around the thighs, between the legs'."

Hunter, writing in 1936, comments on resistance to the practice of virginity inspection from the girls themselves possibly fuelled by the Christian missionaries' argument that the procedure was undignified. The research participants ascribed the changes to the introduction of a new form of contraception, the injectable contraceptive. The inspections ceased "because now this thing of clinics was being introduced, that we should go to clinics to get the contraceptives" (f55).

The new mediational means: Injectable contraception

In the 1970s the South African state began to officially and aggressively promote family planning with a specific focus on fertility levels in the homelands (Brown, 1987; Burgard, 2004). Family planning clinics were sometimes "located across the street from homelands so that women could walk over the border, or were organized at shops frequented by black women when they travelled to the [Republic of South Africa]" (Kaufman, 1998: 422). The injectable contraceptive is a long lasting form of fertility control administered after every three months making compliance relatively easy. It was the contraceptive method most widely distributed by the government's family-planning program because it was cost-effective, easy to administer, and did not require the consent or co-operation of a woman's partner, parents, or in-laws (Klugman, 1993).

There is no denying that the introduction of family planning and contraception has distinct benefits for women because of the risks of ill-health and death related to pregnancy and child birth. In enhancing reproductive choice it also contributes to gender equality in that it enables women to make choices about their lives (Rees, 1995). However, population policy under apartheid in South Africa was a response to racial-group differentials in fertility that created concern about the "swamping" of the white population by black people (Chimere-Dan, 1993; Burgard, 2004). The concern of the apartheid state is captured in a quotation in a classic text on family planning policy and the "black peril": "There is no sense in withstanding the enemy beyond the country's borders while the far more serious population explosion within its borders is allowed to continue unchecked" (Van Rensburg, 1972, cited in Brown, 1987: 256). Although this family-planning programme was perceived by many as an attempt to diffuse the political potential of a majority, and was received by the black population with suspicion, there was a distinct increase in the use of modern contraceptives, particularly the injectable contraceptive (Chimere-Dan, 1993; Burgard, 2004). In fact the use of contraceptives by South African women in the 1980s was the highest in sub-Saharan Africa (Kaufman, 1998). Contraceptive use in South Africa in the 1970s and 1980s was recorded to be the highest amongst black women aged 15 to 24 years, and for never-married women (Burgard, 2004). Contraceptive use is usually related to education, age, and socio-economic status, and this uptake amongst rural women, including those in the research context of the former homeland, may seem puzzling. However, the periodic and often prolonged absence of men because of migrant labour affected reproductive dynamics (Timaeus & Graham, 1989). Chimere-Dan (1996: 7) argues that the development and expansion of segregation policies and the labour migration system "disturbed the marriage market and strained existing marriages to the point of relaxing the norms governing nonmarital and extramarital sexual relationships". The migrant labour system contributed to family fragmentation. Women increasingly headed households and had control over economic and social decision-making, including decisions about reproduction, giving them more latitude to choose to limit their fertility (Burgard, 2004; Chimere-Dan, 1996), although these "choices" were constrained by the gendered circumstances of their lives. Changes in contraceptive norms and behaviour were easily accepted by rural women as part of a "sociocultural and economic adjustment strategy" (Chimere-Dan, 1996: 7).

Apartheid policies thus lead to the introduction of the injectable contraceptive as a new mediational artefact into the activity system, changing the nature of the activity. By nullifying the negative outcome of pregnancy it enabled and normalised penetrative sex. This contributed to the demise of the traditional contraceptive practice of ukumetsha. The introduction of the injectable contraceptive also profoundly affected the division of responsibility for the risks of sexual activity. This will be illustrated through an analysis of the current activity system (reflecting on the time period 1976-2000) highlighting the tensions and contradictions within this phase of the system. This section of the analysis draws on the accounts of the younger research participants in the study (those below the age of 30 years old), and the perspective of the older research participants in their role as parents in this phase of the activity system.

Regulation, monitoring and management of sexual activity in the current activity system

In the current phase of the activity system there are significant changes in the formal mechanisms which monitor, regulate and manage sexual activity. Pregnancy is still a concern and there are still penalties for premarital pregnancy. However the practice of isihewula, the public castigation of the impregnation, has fallen away, suggesting that the formal community "sanctions against seduction and impregnation" (Delius & Glaser, 2002: 46) has all but collapsed. A young male participant (m23) comments about ukumetsha: "No, no, there is no such thing with us [only] real sex".

Although there was still concern about the risk of pregnancy on the part of the younger research participants the injectable contraceptive provided the means to reduce this risk. The availability of the injectable contraceptive meant that fear of pregnancy need not constrain sexual activity, nor act as a deterrent. A young female participant f19 says "I wasn't scared of pregnancy because I was taking the contraceptives". Currently, the injectable contraceptive is available at no cost to users of primary care facilities across the country. These injectable methods are the most commonly used forms of contraception particularly amongst women aged 15 to 49 years and low-income populations (Morroni, Myer, Moss & Hoffman, 2006). Burgard (2004) comments that the reliance on injectable contraception persisted into the post-apartheid era (after 1994) partly because there have been no dramatic changes in social and economic conditions or mass migration out of the former black areas. In the research context, young women go to the local clinic and begin a programme of injectable contraception once they begin menstruating and, or, when they become sexually active. This happens on the directive of their mothers, or on their own initiative, from as young as 14 years of age. As an indication of the fear of the risk of pregnancy some young women use this new mediating artefact even if they are not yet menstruating. Participant f21 comments about a friend: "She lied there [at the clinic] and told them she was already having her periods, so they gave her a contraceptive injection, so she's been going there regularly, but she's never had her period yet".

In this phase of the activity system the regulatory practices around sexual activity seem to have been replaced by parental monitoring and management of contraceptive use concentrated on young women. In fact most of the regulation of sexual activity on the part of elders is still related to pregnancy rather than any other risks. This is evident in participant f55's concern that her daughter avoids pregnancy through family planning: "Well I allow my children to go [and sleep with a boy] when I see that they're old enough to go ... I never actually say 'you can go', but I just allow it to happen. If I catch them at it, then I feel that I have to tell them to go and protect themselves through family planning. What I don't want is for her to get pregnant before time ... "

This regulation of contraceptive use is distinctly gendered. Mothers are galvanised into action either at the onset of their daughter's menstruation, or when they notice them becoming sexually active. Participant f55 says: "With my child, the minute she went on her period, I took her to the clinic for family planning". Participant f27 says: "When I started with my menstrual cycle, I told my mother, and my mother sent me to the clinic for the contraception". Participant f55+ says: "What I did is to send them (my daughters) to the clinic for contraceptives after noticing they have boyfriends". Participant f36-45 says: "... my daughter started (having sex) at fourteen, and I just told her to go get an injection because I can't stop her doing that and I don't go with her to school". One of the youngest research participants f18 says: "... And also when I started getting interested in boys, my mother called me again and said 'My child, I think that you should go to the clinic for contraceptives, because I don't want you to get pregnant'. And she told me that 'I'm not giving you a ticket to sleep around and have every boyfriend in this village, because if you do that you might contract bad diseases'." A male participant (m16-25) said: "... And because my girlfriend was caught by her parents coming out of my house, the following morning she was immediately sent for contraceptives ."

Unlike in the historical phase of the activity system, communication about sex between parents and children is predominantly between mothers and daughters. There was little evidence of fathers or mothers talking to their sons about sex and risks in sexual activity. The content of maternal communication about sex also focussed on obtaining the injectable contraceptive from the local clinic. It did not address other risks in sex such as sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or HIV and AIDS.

The introduction of injectable contraceptives as a mediating artefact has also had a significant effect on the division of labour component of the system. Historically, to mitigate the impact of penalties incurred for causing a premarital pregnancy, both men and women assumed responsibility for the risk of pregnancy. Although these risks were not necessarily carried equally by both male and female partners (for example, women were still responsible for "allowing" men access to their bodies; and women had to obtain men's co-operation to practice ukumetsha), men did assume more responsibility for prevention of pregnancy than they do currently. Men spoke about in the past being willing to use ukumetsha as a form of contraception. However, the availability of the injectable contraceptive reduced the need for this self-regulation and shifted the management of the risk of pregnancy entirely onto the female partner. Participant m36-45 says: "Before sleeping with her... you'd ask whether she's on contraceptives or not". Participant m43 says: "but you would sort of talk to your partner and advise her, [that] she should use an injectable contraceptive, because you would both be aware of the risks of, you know, getting her pregnant and the implications."

Use of the injectable contraceptive is thus a double-edged sword. Although it gives women greater power over their reproductive capacity and sexual health male partners have come to assume that women will take responsibility for avoiding pregnancy. This establishes particular conditions for the use of barrier contraceptive devices in the face of the risk of HIV infection.

Responding to HIV

A significant difference between the historical and the current forms of the activity system is the presence of HIV as a negative outcome of sexual activity. All of the younger research participants, both male and female, were aware of HIV and knew that the barrier contraceptive device of the condom prevented HIV transmission. However, there was a distinct prioritising of the risk of pregnancy over the risk of HIV evident in the concern on the part of the participants with obtaining injectable contraceptives.

In a context of high HIV prevalence condom use is critical because there is no other method (or 'tool' in activity system terms) to prevent the transmission of HIV in sexual activity. In the current phase of the activity system female partners were more likely to raise the issue of condom use. However, unlike other hormonal contraceptives such as the pill or the injection, condom use is a male controlled method and has to be negotiated. For many of the research participants their partner's attitude was a significant obstacle to condom use. Participant f28 comments of her boyfriend: "He said he didn't want it, he wouldn't use it... I want to, but I can't".

The inability to negotiate and insist on condom use is partly because of the gender dynamics in the division of labour of the activity system. Throughout the data were accounts of the male partner's power to control the interaction through proposing the relationship and initiating sex. Older participants commented on the convention that men must initiate sexual activity. Participant m71 says that the woman is a "visitor" and does not "have the right" to initiate sex. This dynamic continues into the current phase of the activity system. One of the younger participants (f15) says "there is no such thing that a girl would start it". Men are in charge of sexual activity and in many cases persuade or cajole a reluctant female partner. Participant f35 says: "... I was very scared and I got more scared after the first time ... and ooohhh.... I found the whole thing painful it was not a very good experience ... he knew but he kept on pushing for it, it didn't matter to him that I didn't like it, he wanted it so he kept pushing for it." Participant f49 comments that even if she is not willing "You are forced to, although you don't want to, and then well, ja, in my case, you are just dead. So he would do on his own, and he would know that I'm not there, until he gives up". Amongst the younger research participants, f18 explains: "I wasn't ready to have sex but my boyfriend saw that I was ready, and persuaded me until I consented". Participant f15 says she would use a condom "if (my boyfriend) would agree that we use condoms then we could use them .". Power within the activity thus resides with the male partner and his desires dominate. In the face of these gendered dynamics women cannot manage the risk of unprotected intercourse and 'make' condom use happen.

In addition to these gender dynamics in sexual activity, condom use was not common amongst youth in the research context. Garenne, Tollman and Kahn (2000) argue that an overemphasis on injectable contraceptives affects motivation for the use of other methods of contraception which operate as protective mechanisms for the prevention of HIV infection. Rees (1995: 33-34) argues that once a "woman is given a highly effective contraceptive method, it is likely that her motivation to use an additional barrier method is greatly diminished". In a context where pregnancy is seen as the dominant risk in sexual activity this risk is nullified through the injectable contraceptive, and responsibility for the risk of pregnancy is placed on women; men do not need to concern themselves with other forms of contraception such as condom use. This is perhaps what underlies the following statement: "Well I'll be honest with you. I know about AIDS. I'm aware that it's a disease that kills. But so far I have never used a condom and I think even among my peers it's quite common that a condom is not used because we do sit and talk about these things. We know AIDS is there but you know we haven't used condoms no, I'll be honest with you" (m23).

DISCUSSION

The assumption in activity theory is that activities are palimpsestic. The current form of the activity system will bear visible traces of its earlier forms. Using the triangular model of the activity system provides a trace of the analytic process and highlights particular components of the system and significant dynamics between these components which illuminate the problems and potentials of the current activity.

Activity systems are inherently characterised by constant construction, renewal and transformation of the components of the system (Engestrom, 1996). Engestrom (1987) identifies different levels of contradictions: primary (within components of the activity system; secondary (between components of the activity system); and tertiary (between activity systems). These contradictions are a "motive force of change and development" (Engestrom & Miettinen, 1999: 9) because as they are aggravated over time, they can eventually lead to a crisis in the activity system and potentially new forms of the activity (Engestrom, 1996). Reading sexual activity in the research context against its own history, particularly shifts in contraceptive practices, has exposed the various disruptions and disturbances which have occurred in its development. For example, the introduction of a new mediating artefact (the injectable contraceptive) into the system initiates a contradiction with intercrural sex as a means (tool) to prevent pregnancy which ultimately leads to a development of the activity from non-penetrative to penetrative sex.

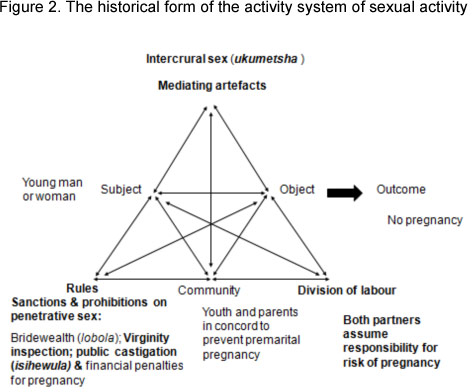

The historical analysis also reveals the way in which the outcome of pregnancy mediated the nature of sexual activity. The power of pregnancy to potentially cause a crisis in the activity system of the family or the social network meant that it played a significant role in the activity system. The dominant tension in the system was thus between being sexually active and the negative outcome of falling pregnant. A set of sanctions and prohibitions on penetrative sex mediated sexual activity facilitated by the contraceptive device of intercrural sex (ukumetsha) which operated as a tool in the system to allow a limited form of sexual release (albeit men's sexual release, thus facilitating sexual gratification for young men while maintaining young women's "purity" and avoiding pregnancy). The social regulatory mechanisms included virginity inspection; financial penalties on premarital pregnancy; public castigation of premarital pregnancy (isihewula); and the payment of bridewealth (lobola). In the community component of the activity system, youth and parents acted in concord to regulate sexual activity to prevent premarital pregnancy. Mothers and fathers assumed responsibility for monitoring sexual activity and educating youth about preventing pregnancy. In the division of labour in the activity both male and female partners assumed some responsibility for preventing pregnancy. This historical form of the activity system is presented in Figure 2. Apartheid policies lead to the introduction of the injectable contraceptive as a form of family planning in contexts such as the research site. This new tool in the activity system normalised penetrative sex as opposed to ukumetsha and generated shifts in the division of labour component of the system. The components in the activity system which were most affected by these changes are indicated in bold.

The analysis of this earlier form of the activity assists in understanding the current activity system, that of contemporary youth in the context of the HIV epidemic. In the current form of the system (see Figure 3 - below) although HIV is present in the system, pregnancy is still the dominant negative outcome of sexual activity. Other studies have also found a focus amongst youth on the prevention of pregnancy rather than prevention of STI transmission (Varga, 1999; Parker et al, 2007). In this new system the risk of pregnancy is nullified by the new mediational means in the system, the injectable contraceptive. This tool displaces intercrural sex and establishes penetrative sex as a norm for the activity.

In the division of labour component of the current form of the activity male youth are aware of the need to manage the risk of pregnancy but they are only peripherally interested and involved in this responsibility. The burden of responsibility for the risk of pregnancy and contraceptive practices now lies with women. Mothers, in particular regulate their daughters' contraceptive use. The new mediational means thus establishes the norms in the division of labour for the management of risk and sexual health entrenching the gendered responsibility for fertility regulation and contraception, a finding which echoes that of a number of other South African studies (Mfono, 1998; Kaufman, 2000; Reddy et al, 2000; Maharaj, 2001).

HIV is present as a new negative outcome in the system and a barrier form of contraception, the condom, is available within the system to prevent HIV transmission. In response to HIV female partners maintain the gendered nature of the responsibility for risk management by, as Wilbraham (1996) argues, assuming a caretaking role, initiating, and even "policing" condom use. However, condom use is dependent on negotiation and the male partner's lack of concern with sexual risk and his power in the sexual interaction mitigate the use of condoms. The new mediational means has thus empowered women to be in control of the risk of pregnancy but the gendered nature of this responsibility compromises HIV risk management.

CONCLUSION

Through describing and analysing the development of the activity system, the historical analysis illustrates how an activity depends on "some historically formed mediating artifacts, cultural resources that are common to the society at large" (Engestróm & Miettinen, 1999: 8). The nature of sexual activity in this research context shifted in relation to the mediating artefact of the contraceptive device, setting up particular dynamics for the management of HIV risk in sexual activity. It is through an historical contextualization of the activity that the palimpsestic nature of current practices is revealed. The problems and potentials of the activity system are thus understood against their own history (Engestróm, 2001).

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to researchers from the Centre for AIDS Development Research and Evaluation (CADRE) for assistance with the data collection. I also acknowledge the valuable comments from the reviewers of this article.

REFERENCES

Brown, B (1987) Facing the "Black Peril": The politics of population control in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 13 (3), 256-273. [ Links ]

Burgard, S (2004) Factors associated with contraceptive use in late- and post-apartheid South Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 35 (2), 91-104. [ Links ]

Burman, S & van der Spuy, P (1996) The illegitimate and the illegal in a South African city: The effects of apartheid on births out of wedlock. Journal of Social History, 29 (3), 613-635. [ Links ]

Caldwell, J C, Caldwell, P & Quiggin, P (1989) The social context of AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review, 15 (2), 185-234. [ Links ]

Chimere-Dan, O (1993) Population policy in South Africa. Studies in Family Planning 24 (1), 31-39. [ Links ]

Chimere-Dan, O (1996) Contraceptive prevalence in rural South Africa. International Family Planning Perspectives, 22 (1), 4-9. [ Links ]

Daniels, H (2001) Vygotsky and pedagogy. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Delius, P & Glaser, C (2002) Sexual socialisation in South Africa: A historical perspective. African Studies, 61 (1), 27-54. [ Links ]

Engeström, Y (1987) Learning by expanding: An activity theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit. [ Links ]

Engeström, Y (1996) Developmental studies of work as a testbench of activity theory: The case of primary care medical practice, in Chaiklin, S & Lave, J (eds) (1996) Understanding practice: Perspectives on activity and context. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Engeström, Y (1999) Activity theory and individual and social transformation, in Engeström, Y, Miettinen, R & Punamäki, R (eds) (1999) Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Engeström, Y (2001) Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualisation. Journal of Education and Work, 14 (1), 133-156. [ Links ]

Engeström, Y & Miettinen, R (1999) Introduction, in Engeström, Y, Miettinen, R & Punamäki, R (eds) Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Garenne, M, Tollman, S & Kahn, K (2000) Premarital fertility in rural South Africa: A challenge to existing population policy. Studies in Family Planning, 31 (1), 47-54. [ Links ]

Hunter, M (1936) Reaction to conquest. London: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Kaufman, C E (1998) Contraceptive use in South Africa under apartheid. Demography, 35 (4), 421-434. [ Links ]

Kaufman, C E (2000) Reproductive control in apartheid South Africa. Population Studies, 54 (1), 105-114. [ Links ]

Kaufman, C E, de Wet, T & Stadler, K (2001) Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood in South Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 32 (2), 147-160. [ Links ]

Klugman, B (1993) Balancing means and ends: Population policy in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters, 1 (1), 44-57. [ Links ]

Lave, J & Wenger, E (1991) Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Leclerc-Madlala, S (2003) Protecting girlhood? Virginity revivals in the era of AIDS. Agenda 56, 16-25. [ Links ]

Maharaj, P (2001) Male attitudes to family planning in the era of HIV/AIDS: Evidence from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 27 (2), 245-257. [ Links ]

Mayer, P & Mayer, I (1970) Socialization by peers: The Youth Organisation of the Red Xhosa, in Mayer, P (ed) Socialization: The approach from social anthropology. London: Tavistock. [ Links ]

Mfono, Z (1998) Teenage contraceptive needs in urban South Africa: A case study. International Family Planning Perspectives, 24 (4), 180-183. [ Links ]

Morroni, C, L, Myer, M, Moss, M & Hoffman, M (2006) Preferences between injectable contraceptive methods among South African women. Contraception, 73 (6), 598-601. [ Links ]

Parker, W, Makhubele, B, Ntlabati, P & Connolly, C (2007) Concurrent sexual partnerships amongst young adults in South Africa: Challenges for HIV prevention communication. Johannesburg, South Africa: CADRE. http://www.cadre.org

Reddy, P, Meyer-Weitz, A, Van den Borne, B & Kok, G (2000) Determinants of condom-use behaviour among STD clinic attenders in South Africa. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 11 (8), 521-530. [ Links ]

Rees, H (1995) Contraception: More complex than just a method? Agenda 27, 27-36. [ Links ]

Roth, W-M & Lee, Y J (2007) Vygotsky's neglected legacy: Cultural-historical activity theory. Review of Educational Research, 77 (2), 186-232. [ Links ]

Scorgie, F (2002) Virginity testing and the politics of sexual responsibility: Implications for AIDS Intervention. African Studies, 61 (1), 55-75. [ Links ]

Timaeus, I, & Graham, W (1989) Labor circulation, marriage, and fertility in Southern Africa, in Lesthaeghe, J R (ed) Reproduction and social organization in Sub-Saharan Africa, Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Tolman, C (2001) The origins of activity as a category in the philosophies of Kant, Fichte, Hegel and Marx, in Chaiklin, S (ed) The theory and practice of cultural-historical psychology Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press. [ Links ]

UNAIDS (2011) World Aids Day Report 2011: How to get to zero: Faster. Smarter. Better. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS. [ Links ]

Van der Riet, M (2009) The production of context: using activity theory to understand behaviour change in response to HIV and AIDS. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Varga, CA (1999) South African young people's sexual dynamics: Implications for behavioural responses to HIV/AIDS, in Caldwell, J C, Caldwell, P, Anarfi, J, Awusabo-Asare, K, Ntozi, J, Orubuloye, I O, Marck, J, Cosford, W, Colombo, R & Hollings, E (eds) Resistances to behavioural change to reduce HIV/AIDS infection in predominantly heterosexual epidemics in third world countries. Canberra: Health Transition Centre. [ Links ]

Wilbraham, L (1996) Avoiding the ultimate break-up after infidelity: The marketisation of counselling and relationship-work for women in a South African Advice column (1). PINS (Psychology in society), 21, 27-48. [ Links ]

1 This contentious practice has re-emerged in contemporary times as an AIDS prevention strategy (Scorgie, 2002).

2 Residential areas outside of white towns set aside for black people during the apartheid era. 29